A Petition to Cromwell on Right Rule: [Several Hands], The Onely Right Rule for Regulating the Lawes and Liberties of the People of England (28 January 1652).

Introduction

This Leveller Tract is part of a larger collection of Leveller Agreements of the People, Petitions, Remonstrances, and Declarations (1646-1659) which are some of the earliest attempts to draw up proto-constitutions to limit the power of government and defend the liberties of the people. They are available in an iFrame format or as individual pamphlets which can be viewed or downloaded separately.

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

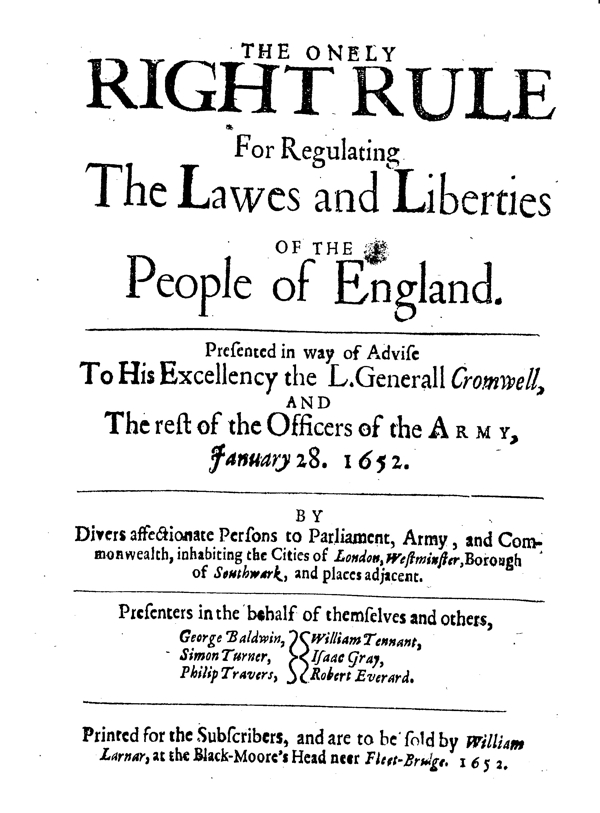

T.228 [1652.02.28] (7.11) [Several Hands], The Onely Right Rule (28 January 1652).

Full title

Several Hands, The Onely Right Rule for Regulating the Lawes and Liberties of the People of England. Presented in way of Advise to His Excellency the L. Generall Cromwell, and the rest of the Officers of the Army, January 28. 1652. By divers affectionate persons to Parliament, Army, and Commonwealth, inhabiting the Cities of London, Westminster, borough of Southwark, and places adjacent. Presenters in the behalf of themselves and others, George Baldwin, Simon Turner, Philip Travers, William Tennant, Isaac Gray, Robert Everard.

Printed for the subscribers, and are to be sold by William Larnar, at the Black-Moore's

Head neer Fleet-bridge, 1652.

Estimated date of publication

28 January 1652

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

Not listed in TT.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE L. Generall Cromwell, AND The rest of the Councell of the Army OF THE Commonwealth of England;

The humble and faithfull advice of divers affectionate Friends to the Parliament, Army and Commonwealth of England.

HEaring of your especiall meetings in Councell in order to the setling of the Nation in Peace and Freedome, as persons alwayes ingaged with you in affection and indeavours to the same just ends, and alike concerned in the issue and successe thereof; and knowing by sad experience how prone the wisest have been to mistakings in affairs of this nature, we have deemed our selves bound in conscience to contribute what we conceive requisite, or may be of use for the steering of your course aright, and for the avoyding of those rocks upon which many have fallen for want of due and timely consideration: which cannot be avoided but by a cleare knowledge of the Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties of England, and by a firm resolution to restore every of them without partiality unto their primitive power and efficacy throughout the Land; notwithstanding any corrupt interest, built upon their ruines or abuses.

So that waving all things of innovation (let pretences be never so specious) the first thing necessary to the work you have undertaken, is to satisfie your understandings, what are those Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties, and in the next place by all lawfull means to endeavour their restauration. For, as you once well argued, you are not a mercenary Army, hired to serve any arbitrary power of State (such was the late Kings Army, fighting against the Fundamentall Lawes, to erect his will or corrupt Lawes by former Kings procured subservient to will and power) but called forth and conjured by the severall Declarations of Parliament to the defence of your own and the Peoples just Rights and Liberties, which our Ancestours of famous memory have endeavoured to preserve with the price of their bloud, and you by that, and the late bloud of your deare friends and fellow-souldiers (with the hazard of your own) do now lay claime to; these are your own reasonings when first you disputed the Authority of Parliament, they having first declined the Fundamentall Lawes, which was the onely just ground of declining them.

And as you rightly understood, that being no mercenary Army, but called forth to the defence of your own and the Peoples just Rights and Liberties, you were not bound to obey commands, though of a Parliament, contrary to the Fundamentall Lawes, so much more now are you to understand, That of any men in the world it would worst become you, to be either advisers or procurers of other things then those very true ancient fundamentall Rights and Liberties.

And you see likewise, that notwithstanding the many professions and Protestations of this Army, to maintain the Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties of this Nation, it yet remains under a greater degree of bondage, and fuller of just complaints then ever, because you have slackened your zeale, and there hath not been that diligent perseverance in all lawfull indeavours until their plenary restauration and firm establishment: Your study ought not to be like Conquerors, to make things new, or innovate upon the Fundamentall Lawes (that never-failing means of trouble and confusion) but to cleare them from those many incroachments, violations and abuses both upon the Lawes themselves, and the execution of them, which have almost rendred them of no benefit, and full of vexation to the people of this Nation.

You may please to observe, it is not the being of a Parliament that makes the Nation happy, but their maintaining of the fundamentall Rights and Liberties, nor that in words onely and Declarations, but in the reall and effectual establishment of them; and when they either neglect those, or set up other things contrary, or oppose the establishing of them, they prove themselves enemies, and reduce this Nation into a condition of bondage.

Be pleased to review your Remonstrances and Declarations which in all parts of them have held forth the clearing, setling and securing of the Rights, Liberties, and peace of the Nation, the only justifiable end of all your publique motions and endeavours, appealing to the whole Nation, to the world, and to Almighty God, for the justnesse, reasonablenesse, and common concernment of your desires and intentions therein, yea so wisely carefull were ye over the common Rights and Liberties of the people, and of their safety, that you proposed that in things clearly destructive to those Rights, there might be for the future a liberty for dissenting Members in the Parliament to enter their dissent, and thereby to acquit themselves from the guilt or blame of what evills might ensue, that so the people might regularly come to know who they are that performe their trust faithfully, and who not, an argument amongst others then urged by the Army, importing the greatest zeal and sincerity, to the restoring of the Fundamentall Lawes, that could possibly be expressed.

Nor is there (as we verily believe) any just objection, that should stagger you in perseverance accordingly, although we cannot deny, but that all the old and new Sophisms and delusive arguments devised by corrupt interests, in defence of themselves against the Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties of the people, have been so diligently blown abroad, that we find they have captivated many good mens understandings, and are ready and uppermost almost in all discourses, urging that if you now endeavour the restauration of the antient Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties of England, you seek to re-edifie the things you have thrown down, as Kingly government, which the Parliament, not without sufficient grounds, voted to be uselesse, burthensome, and dangerous; for what, say they, hath been more antient in England, unto which even by the very Lawes were annexed large revenues, and extraordinary trusts, as the Militia, and the like? what more antient authority then the House of Lords, which by the very Lawes of England had Jurisdiction in appeals after Judgement, and both Kings and Peers ever esteemed an essential part of Parliaments; the Bishops likewise of long continuance, and very many Lawes extant in favour of them.

But as truth is more antient then error, and righteousnesse was before sinne, though error and sinne have much to say for their antiquity, so is it answered in these and the like cases; though Kings, and Lords, and Bishops have been of long continuance, and have procured many Laws to be made in severall times, by Parliaments in favour of them, yet upon due examination it will appear, that they are not of Fundamentall Institution, no more then many other corrupt interests, yet extant, which time after time have one made way for another, untill at length they got the sway of all things, sate themselves upmost in all places, oft times filled the seats in Parliament, and then made Lawes in favour of themselves, and each others interest, and in subversion of the Fundamentall Lawes, endeavouring all they could utterly to root them up, and to boot the knowledge of them out of all remembrance.

And therefore to find out what are truly Fundamentall Institutions, you may please to look beyond Kings, and as you passe them, you will perceive that their originall was either by force from without, or from confederacy within the Land, that of their confederates they made Lords and Masters over the people, created offices, and made their creatures officers for life, whereas the true mark of a Fundamentall Institution is only one years continuance in an office, by which mark it is evident, that neither Kings nor House of Lords are of Fundamentall Institution, all true Fundamentall Institutions ordaining election to every office, which is another mark, and that by the Inhabitants of the place where the office is to be exercised; and another speciall mark is, that the main scope and intent of the office and businesse thereof, is of equall concernment to the generall good of all the people, and not pointed to make men great, wealthy and powerfull, all which undoubted marks exclude not only Kings, and Lords, and Bishops, but many other interests of men in this long enslaved and deluded Nation.

So that in removing these uselesse, burthensome and dangerous interests of Kings, Lords, and Bishops, no violence at all hath been done to the Fundamentall Lawes and Liberties of England, but they are so farre cleared and secured from innovation, and many oppressions which attended them.

Nor is there ground for any to suppose, that in restoring the true antient fundamentall Rights of England, there will be a necessity of maintaining any the Courts in Westminster, or their tedious, burthensome or destructive way of proceeding in trial of Causes, both Chancery, and the rest being in all things (except the use of Juries) all of them of Regall institution except the Common Pleas, which is so also, as to its being seated in Westminster: These have sometimes been strengthened by Laws made in Parliaments, which were ever to give place to Fundamentals, being indeed null and void, wherein any particular they innovate upon, or are contrary unto then: All causes by the fundamentall Laws being to be decided and finally ended, past all appeal, in the Hundreds, or County Courts, where parties reside, or where the complaint is made by Juries, without more charge or time then is necessary, so that untill the Norman Conquest, the Nation never knew or felt the charge, trouble, or intanglements of Judges, Lawyers, Attorneys, Solicitors, Filors, and the rest of that sort of men, which get great estates by the too frequent ruines of industrious people, which is another mark to know that all such are not of fundamentall institution, but Regall, and erected for the increase and defence of that interest.

As for those defects which are many times observed in Juries, and some inconveniences which ensue in some cases under other fundamentall Constitutions; it is to be noted, that there is not perfection to be expected in any Government in this world, it being impossible for the wisest men that ever were to compose such Constitutions, as should in every case warrant a just event. Yet so carefull have our Forefathers been, that the Laws of England are as preventive of evill, and as effective for good, as any Laws in the world.

And for Juries, whatever just complaint lies against them, it doth not relate to the Constitution itselfe, (which Kings have often attempted to destroy, as the main fortresse of the peoples liberty) but against such abuses, in the packing and framing of Juries, in their bypassing or over-awing, by the servile and partiall Officers about the Courts, by the Kings Sheriff, or under-Sheriff, and other, by-wayes, that others have found out; all which abuses are matters of just complaint, and require rectification, and ought not to be made use of as a ground of Innovation, or an argument against your fundamentall Constitution.

Others there are, who finding the great importance of Juries to preserve the people’s Liberties, and that through the sense that the people have thereof, it will be but a vain thing to attempt the totall taking them away, have invented a stratagem that will render them instead of being a fountain of equall Justice to the people, the means only of advancing the rich, and an awe upon the middle and meaner sort of men, which they would do upon the common pretence of Prerogative, that onely men of estate and quality ought to be entrusted with the determination and decision of causes, and therefore have contrived that such only as are worth one hundred mark per annum, should be capable of being chosen Jury men, which if obtained, we cannot from thence but make these conclusions.

1. That the Fundamentall Constitution is thereby violated, which gives equall respect to all men, paying Scot and Lot in the places they inhabit.

2. By the same liberty they alter the Constitution in this particular at this time, they may at another time totally take it away.

3. That it is a policy agreeable to that of Kings, in reducing the power of Judgement into the hands of a few, and the rich, who may with much more ease be corrupted, then the generality: It being also a bringing of this Nation to the condition of the French, and making it consist only of Gentleman and Pesants.

You may be pleas’d in the next place to consider the particular of Pressing, or forcing men to serve in the warres against their consents, then which nothing is more contrary to fundamentall liberty; the King did alwayes make use of it, and such abroad, whose government has not that goodnesse and freedome in it, as to invite men voluntarily to its defence; a good government cannot need it, since in that it would be the interest of every man to hazard his life and fortunes for its conservation, and therefore we desire that this antient liberty may be tenderly preserved.

For Tythes, they may (we conceive) be taken away, without violence to any fundamentall Law; the institution thereof being Popish at first, and partly Regall, afterwards changed solely into the Regal Interest, to maintain a numerous sort of ble Sophisters, under pretence of being Ministers of Christ (which they were not) having no qualifications agreeable unto those which were so indeed, to preach up the Regall Interest with their own: Fundamentall institution imposeth no charge upon the people, but for maintenance of the impotent and poor, or for such as are restrained untill time of triall for want of Sureties: All which the Neigabourhood is to levy, or for publique defence against enemies, which is referred by Fundamentall Constitution unto annual chosen Trustees in the Grand Councell of the people, called from the Norman Parliament, upon whom the continued labours and policies of the Conquerors successors have had great influence, by whose endeavours this burthen of Tythes came to have the colour of Law set upon it, though in this, as in all things els, Parliament Law was ever to give way to Fundamentall, being null and void in it selfe, where it innovates upon the antient Rights of the people, and hath been so acknowledged, enacted, and declared by most Parliaments; of so Supreme Authority in this Nation have fundamentalls ever beene, whereof Annuall new elected Parliaments is one and a chiefe, being instituted for preservation, and not for destruction of fundamentalls, for then it might null Parliaments themselves, which could never be within the trust of Parliaments.

But yet so unhappy have Parliaments been in most times since the Conquest, that waving their care of the fundamentall Liberties of the Nation, they have so multiplied Laws upon Laws to their prejudice, that the whole voluminous bulk of the book of Statutes serves but as a witnesse of their defection, and of the prevalence of the Regall interest and his adherents; of which deviation from their rule (the Fundamentall Law) not any one thing is more remarkably pernicious to industrious people, then this of tythes, or inforced maintenance for Ministers, or any other sort of men, except such as are afore-mentioned; so that tythes being utterly abolished, the people are delivered from a most heavy and grinding oppression, and therein restored to Fundamentall Liberty.

And as for those Laws which have been, touching mens Judgements, opinions and practise in matters of Religion, with the proceedings thereupon, and punishments annexed, there is no ground at all for them, the Fundamentall Law of England being as free and clear from any such persecuting spirit, as the Word of God is; questioning none, nor permitting that they should be questioned, or otherwise molested, much lesse punished, but for such things only, as whereby some other person is injured, in person, goods, or good name, or in wife, children, or servant, and therein also it provides, that none be tortured upon any occasion whatsoever, and that no lesse then two lawfull Witnesses are sufficient to prove every fact: Also, that where any accused person can procure Sureties, there be no restraint of the body in prison; what is in common practise contrary hereunto, hath been innovated contrary to Fundamentall Right, and may lawfully be reformed and reduced to its originall state again, and thereby also the people restored to antient right therein, and freed from abundance of mischief and inconvenience.

And so extremely doth the Fundamentall Constitutions of England regard true freedome, that it allows of Bail in any case, without exception, where it can be obtained, and admits no imprisonment of the persons of any for debt, choosing rather that one man should suffer in his estate, then that the bodies of men and women should be, as it were, buried alive in goales and prisons, as thousands have been, and still are, to the hearts grief of all tender hearted people.

But then the fundamental Law provides, that where there is any estate, there satisfaction is to be made, as far as it will reach, leaving still some necessaries for life, otherwise it were more grievous for poor debtors, then for many sorts of wilfull malefactors; for however the present practise is, and long hath been, by the fundamentall Law, the estate even of a capital offender that suffers death for his offence, is not forfeited, but descends to his family, as other mens, after satisfaction made to the parties damnified: These forfeitures no doubt have been the principall cause that many an innocent mans life hath been unjustly taken away, and many a worthy honestman come to be burn’d in the hand; and however Parliaments have been drawn in to countenance such practises, it was the invention of Kings to turn families upside down at pleasure, for to them their forfeitures went, and they gave them to their creatures and Sickovants, so that here you see is work enough for a well-minded Parliament to remove these evills, and to restore our rights in these and many other grand particulars, without interchanging or innovating upon the true Law of England.

The most unreasonable descent of inheritances to the eldest sonne onely, is also no part of the Fundamentall Law, but quite contrary thereunto, that honestly and conscionably provided, that all inheritances should discend to all the children alike, chusing rather that some ill-deserving children should have where they deserve not, then that it should be at the will of parents, or in the power of the Law, to expose many to such inconveniences, and destructive courses, which younger brothers for the most part hath been cast upon: Divers other branches there are of the Fundamentall Law, as is that concerning Juries, the Liberty of Exception against thirty five, without shewing cause, and of as many more as cause can be justly alledged against, untill the party doth evidently see an indifferency in his Tryers, As also to admit no examination of any against themselves, nor punishment for refusing to answer to questions, Nor conviction without two lawful Witnesses at the least; and that it is the duty of the Officer of the Court to declare to every person these his Rights, and to bring them to remembrance, if neglected to be demanded; all this shewes that the Fundamentall Law of England is a Law of Wisdome, Justice and much mercy, such as God will blesse, chosing in all cases rather that some guilty persons should sometimes escape, then that one innocent person should causlesly be condemned.

And whereas it hath beene supposed, that the punishment of theft by death is fundamentall, it is a meer mistake, it, as most other like things, being an innovation, and no way tending to the lessening of offenders, but rather to their encrease, and indeed necessitating, or strongly tempting every one that robs, to murther also: For as the practise long time hath been, one witnesse even of the party himself that is robbed sufficeth for proof, and casts the thief for his life, what way then is more safe for the thief, then to murther whom he robs, to prevent his testimony against his life, seeing he dies, if proved a thief, and can do no more if proved a murtherer? Besides, when the Fundamentall Constitution was in force, it punished offenders according to the nature of their theft, some by pecuniary inulcts, others by corporall punishments, with laborious workings and open shame, at which time it is testified, that a man with much money, or moneys worth, might have travelled in safety all over England with but a white riband in his hand; besides, the Law of death for theft is many times the means why robbers escape, for that many good and tender-hearted people, either upon the consideration above-mentioned, decline prosecution, because if they should prosecute, they must either sweare falsly, and undervalue what they lost, or take away life, where in conscience they judge they ought not; all which would not be, were the punishment proportioned to the offence, as in the Fundamentall Law it is.

As much likewise may be said concerning the servile tenures of Copyholds, how long soever they have been, they are the slavish remains of conquest, inconsistent with true freedome, or the Fundamentall Law of England, and may, and as the rest forenamed, ought to be reduced to the true state of antient right, and the people thereby freed from abundance of torment, and vexation of Spirit.

All Monopolies at home, and all restraint of trade abroad to distinct companies of men, are all opposite to the antient rights of the people, and may justly be reduced to a universall freedome to every Englishman, which will make trade in time to flourish, and wealth and plenty of all necessaries to abound, especially if the way of raising money by custome and Excize were laid aside, being utterly destructive to trade, and rendring the lives of tradesmen tedious and irksome to them, and hath no consistence with Fundamentall right; for according to that rule, no imposition ought to be laid upon trade, but what moneys are at any time found needfull by Parliament, ought to be levied by way of Subsidy, or an equall proportion upon all mens estates, reall and personall, in which course the whole, within two pence or three pence in the pound, is brought into the publike treasury, whereas in the other way, vast sums go to the maintenance of Officers, so as you perceive in this and all other particulars hitherto recited, the most antient right is not only due, but most for the ease and good of the people, you may perceive by what hath been expressed what are our antient rights, and what, how many, and how great have been our almost as antient wrongs and oppressions.

Some of our antient rights remain alive to this day, as Parliaments and Juries, the first of which ought annually to be chosen, which annuall choice hath for many years been intermitted, and that inherent right withheld, which should have some special thing for its excuse, and happy were the people, and doubtlesse happy would it be for this present Parliament also, that it may truly be said they held the Parliamentary power so long, that they might restore the people to their antient native rights, the Fundamentall Laws, to their full force and power, for which end it was, as you declared, that you reserved these, when you excluded the rest; and therefore surely in this and many more respects you are obliged to persevere in putting them in mind thereof, and if you find that they are not able to agree in the performance of this, the proper work of Parliaments then to move them in some short time, to order a new Parliament to be chosen, that they may take place of them, it being in no wise safe for the Parliament to dissolve, untill the new immediately ready to sit when they rise; nor would we for any thing in the world, that Parliaments should be accustomed to be forced, nothing being of more dangerous consequence to Government it self.

Which endeavours and desires we shall be ready to second you in, and we trust you will not omit to do it by way of Petition with all possible speed, that the desires of good men may be satisfied, in seeing this Parliament yet honour themselves, and blesse the Nation with the proper fruit of their so many years labour, hardship and misery, the re-injoyment of their birth-right; Or if that cannot be obtained, you and your friends desiring it, they will not defer to give up their trust into the hands of another Parliament, which when you understand, we shall then desire you to acquaint the people what their antient rights are, and how and by what interests of men they have been withheld from them, that so they may at length beware, and not chuse such men to make them free, whose interest, advantage, and way of living, binds to keep them in perpetuall bondage: And to inform them likewise, that it is not Statute Law, nor the opinion of Judges, and book-cases, not the Prerogative of Princes, Lords, and great ones, nor any thing but their Fundamentall Rights that can render them free or happy, and to perswade them no longer to give ear to such charming as hath been to their bondage and misery: And that you will be as strongly provided against all motions of Innovation, as against the worst of enemies, though they should assail you with seeming arguments from Scripture, the Scripture giving no particular rules for the Government of Nations, the Government of the Israelites being only intended for them, and either binds not, or els it binds in all and every part; so as those who require tythes by that Law, or punish some offences according to that Law, are bound also to circumcise, and to offer Sacrifice, and indeed to fulfill the whole Law, none having power to make choice of one part, and refuse another.

If they urge from the Gospell, that indeed gives most blessed rules for faith and conversation, but as to Government, it is apparant from those words of our Saviour, (who made me a divider of inheritances) that the Gospel intends not so much earthly, as heavenly things; but both old and new Covenants agree in this, that all just agreements and contracts amongst men, (such are our Fundamentall Lawes) ought inviolably to be kept and observed.

The sense of the Law of God is cleare in this, that it is a cursed thing to remove the land-marks of forefathers; nor are any more highly approved of by God himself then the Rechabites, for walking stedfastly in the laws and constitutions of their forefathers.

Nor can any thing be more destructive to Government or humane Society, then for men to admit that they are not obliged to observe the Fundamentall just Institutions of the countrey wherein they were born, there being nothing that tendeth so readily to the shaking of a well-bounded society of men into anarchy and confusion: For, what is it that gives any man propriety in what he hath but Fundamentall Law? What is it els that defends propriety, but Fundamentall Legall Power? Why have you, and we, and thousands more so cried out upon such as pretended a Prerogative above Fundamentall Law, and above Parliaments, but that it was in subversion thereof? Why did our Forefathers and all their posterity, down to our selves, so heavily complain against the with-holding of Parliaments, and against triall of Causes by any other way but by Juries, but that they are both Fundamentall? Why was it alwayes noted as a mark of regall prevalencie in Parliaments when any thing passed there contrary to those ancient Rules? Why upon all complaints of oppression are the amendments alwayes made by that Rule, as that when Parliaments had been deferred, and complaint made, the remedy runs thus: For remedy of grievances and mischiefs which daily happen, a Parliament shall be chosen once every yeare according to Law: where it is evident, the Law was more ancient then the Act of Parliament or amendment.

Also after abuse and innovation in triall of Causes the amendment comes and sayes, That no man shall be attached, fined, imprisoned, exiled or deprived of life, limb, liberty or estate, but by Iuries, according to the Law of the Land: Which shewes the Fundamentall Law to have been time out of mind before Magna Charta or any Statute Law. Why when after judgment in the legall Courts, the Chancery and Parliament had taken cognizance of the same Causes by way of appeale, doth the amendment come and say, henceforth after judgment in the legall Courts the parties shall be in quiet and free from being called either into Chancery or into Parliament, according to the Law of the Land, but in respect to the supremacy of Fundamentalls? Why were Petitioners in former times so carefull not to insert the least syllable contrary to the Fundamentall Law, but that they knew Parliaments were chiefly ordained for their preservation? And it will not be throughly well in England, till Parliaments make answer to Petitioners according to the Rule of the Fundamentall Law. The late Worcestershire Petitioners for Tythes may then know what they may justly expect from them, viz. that they are at liberty either to give or pay tythes, or any other proportion of their incombs, to such whom they will contract with for their labours in teaching divine things, or any other kind of learning, but those that approve not of paying, are not to be enforced; and thus in all things are the English free, wherein their neighbour is not violated.

Had this rule been observed of late years, it had e’re this stopt the mouths of many Petitioners, and begot a better understanding amongst the people, who have been shattered into shivers for want of this principle to unite them, every man stirring and contending as for life for his own opinion; one will have the Parliament do this, another that; others gathering themselves together in knots, and boasting how many hands they had to their petition; a second sort of men to theirs, and so of the rest, how many friends they had in the House for this thing, how many for that; and thus like the builders of Babel, they have been devided for want of knowledge, and fixednesse in and upon the Fundamentalls, which only can give rest to the spirits of the English, the goodnesse whereof having been once tasted, would soon beget a reconcilement; and doubtlesse this way or none must come the true and lasting peace amongst our selves, and by this means only can we ever be made considerable, either against obstinate corrupt interest at home, or against foraign pretenders and enemies abroad, who otherwise observing us to be a floating unbalanced people, and consequently divided and subdivided within our selves, will never cease to disturb this Nation; whereas were we once again bound and knit together with this just and pleasant ligament of fundamentall Law, divide and reign, would not be so frequent in their vanquisht mouths, which indeed is the main ground of the hopes.

Consider we beseech you, how uncertain the rule of prudence and discretion is amongst the wisest and best of men, how unstable that people were that should be every year to make their Laws, or to stablish them, have we not found the Proverb verified, So many men, so many minds; this thing voted by one sort of men as most just and necessary, yea mens estates, and lives, and consciences cast upon it, and those the best of men, when in short time after the same voted down as most unjust and pernicious; infinite instances of this kind we doubt not will come to your remembrance, and therefore not without good cause have our Predecessors given such dear respect to their Fundamentall Rights, that unlesse mens understandings were even bewitched with the sallaries of corrupt interest, they would choose rather to lose their lives, then to part with one of them, esteeming every man, though born in England, no more a true Englishman, then as he maintained the Fundamentall Liberties of his Country.

To conclude, none ever yet denied that we had Fundamentall standing Laws, and such as against which no Statute Law ought to be obeyed; but endeavours you will find have been in all ages for powers to establish themselves, and govern by discretion, upon a pretence of more easie and speedy dispatch of justice, as the late King did, when he by power brake up the short Parliament; before this, he publikely declared, that he and his Lords would with more speed and better justice redresse the grievances of the people, then the Parliament could do.

And though this hath been a disease incident to the strongest to give Laws and inforce them upon the people, yet as it is manifestly against the Fundamentall Rights of the people of England, which you have professedly fought to restore, and not to destroy, having conquered their enemies, not their friends, so have you by Declarations laid grounds against such temptations; and as abhorring all such wicked and unjust intentions, would not have any entertain any such suspition of you; we have very great hopes, that as you will carefully preserve your hands, your strength, and power from being defiled, by imposing Innovations, or continuing such as have been brought upon us, or yet by being instrumentall to such as would, so we trust, and earnestly intreat that you would lay the premises to heart, and by wisdome and perseverance, procure the antient good Laws of England to be re-established amongst us, they being so just, so mercifull, so preservative to all peaceable minded people, so unburthensome to the industrious, so opposite to all self-interest so corrective of any manner of wrong, so quick in dispatching, so equall in the means, so righteous in their judgements, proportioning punishments to offenders, so tender of the innocent, so consonant to right reason, and having no disproportion to all true Christian doctrine, that the goodnesse of them, as well as because they are the tyes, the Bonds and Ligaments of the people, and both your and our Rights and chiefe inheritance, we trust will cause you, like the true sons of your worthy and valiant Ancestor, to be enamored of them, and to be now much more of the same mind, then when you professed that you esteemed neither life nor livelyhood, nor your neerest relations, a price sufficient to the purchase of so rich a blessing, that you, and all the free-borne people of England might sit down in quiet, under the glorious administration of justice and righteousnesse, and in full possession of those Fundamentall Rights and Liberties, without which we cannot be secure of any comfort of life, or so much as life it self, but at the pleasure of some men, ruling meerly according to will and power.

And may the integrity of your hearts so appear in all your actions, as may render you well-pleasing in the sight of God, who hath registred all your Vows (of freeing this Nation from all kinds of bondages) in the dayes of your distresse: Keep therefore your hearts faithfull; As Moses, who when he was to lead the Israelites out of Ægypt, would not leave a hoof in bondage: and in so doing onely, will you be the rejoycing of this Nation to all generations.