A Foreword by Rose Wilder Lane to Social Fallacies (Economic Sophisms) by Frederic Bastiat (1944).

[Created: 17 August, 2014]

[Revised:

31 January, 2023]

|

|

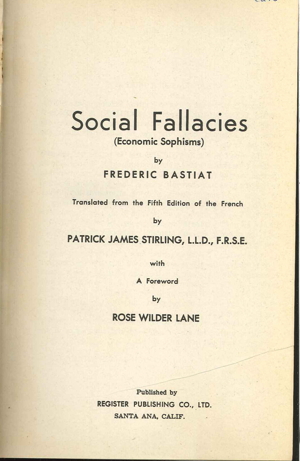

[Title page of the R.C. Hoiles edition of Bastiat's

Economic Sophisms (1944) with an intro by Rose Wilder Lane] |

Rose Wilder Lane (1886-1968) |

Introduction

Rose Wilder Lane (1886-1968) was an American individualist and libertarian who was very important in the founding of the modern American libertarian movement in the mid-20th century. Jim Powell has correctly called the trio of women Ayn Rand, Isabel Paterson, and Rose Wilder Lane as "Three Women Who Inspired the Modern Libertarian Movement" or as one might also call them "the founding mothers of the American libertarian movement". They were staunch opponents of socialism, advocates of natural rights, and limited government at a time when there were few defenders of such ideals. They also who wrote three important books in the same year of 1943: Lane, The Discovery of Freedom, Isabel Paterson, The God of the Machine, and Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead.

The year after her book appeared she was asked to write a foreword to an edition of Bastiat's Economic Sophisms which was published by R.C. Hoiles the newspaper owner and publisher of "Freedom Newspapers" who was based in Santa Ana, CA. This was an important moment when Bastiat's free trade and free market ideas were re-introduced to America. In her foreword Lane provides a remarkable survey of the rise and fall and possible rise of liberty again over the previous 200 hundred years, and placed the work of Bastiat in the context of this historical movement.

See, Jim Powell, "Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, and Ayn Rand: Three Women Who Inspired the Modern Libertarian Movement", The Freeman (FEE, May 1, 1996).

Source

Social Fallacies (Economic Sophisms) by Frederic Bastiat. Translated from the Fifth Edition of the French by Patrick James Stirling, L.L.D., F.R.S.E. with A Foreword by Rose Wilder Lane (Published by Register Publishing Co., Santa Ana. Calif. 1944).

- facs. [PDF 5 MB] of the "Publisher's Statement" and Lane's "Foreword."

Table of Contents

- Introductory Matter

- Translator's Preface (Stirling)

- Publisher's Statement (Hoiles)

- Forword by Rose Wilder Lane

Introductory Matter to Bastiat's Social Fallacies (1944).↩

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE ↩

Bastiat's two great works on Political Economy - the SOPHISMES ECONOMIQUES, and the HARMONIES ECONOMIQUES - may be regarded as counterparts of each other. He himself so regarded them: "the one, he says, pulls down, the other builds up."

His object in the SOPHISMES was to refute the fallacies of the Protectionist school, then predominant in France, and so to clear the way for the establishment of what he maintained to be the true system of economic science, when he desired to found on a new and peculiar theory of value, afterwards fully developed by him in the HARMONIES. Whatever difference of opinion may exist among economists as to the soundness of this theory, all must admire the irresistible logic of the SOPHISMES, and "the sallies of wit and humour," which, as Mr. Cobden has said, make that work as "amusing as a novel."

The system of Bastiat having thus a destructive as well as a constructive object, a negative as well as a positive design, it is perhaps only doing justice to his great reputation as an economist to put the English reader in a position to judge of that system as a whole. Hence the present translation of the SOPHISMES is intended as a companion volume to the translation of the HARMONIES.

It is unnecessary for me to say more here by way of preface, the gifted author having himself explained the design of the work in a short but lucid introduction.

PATRICK JAMES STIRLING.

CONTENTS

FIRST SERIES

CHAPTER

Publisher's Statement ... 1

Foreword by Rose Wilder Lane 3

Introduction 9

I. Abundance-Scarcity 13

II. Obstacle-Cause 22

III. Effort-Result 26

IV. To Equalize the Conditions of Production 34

V. Our Products Are Burdened with Taxes 50

VI. Balance of Trade 56

VII. Petition of the Manufacturers of Candles, Waxlights, Lamps, Candlesticks,

Street Lamps, Snuffers, Extinguishers, and of the Producers of Oil, Tallow,

Resin, Alcohol, and, generally, of everything connected with Lighting 60

VIII. Differential Duties 65

IX. Immense Discovery 66

X. Reciprocity 70

XI. Nominal Prices 73

XII. Does Protection Raise the Rate of Wages? 77

XIII. Theory-Practice 81

XIV. Conflict of Principles 87

XV. Reciprocity Again 91

XVI. Obstructed Navigation Pleading for the Prohibitionists 93

XVII. A Negative Railway 94

XVIII. There Are No Absolute Principles 95

XIX. National Independence 98

XX. Human Labour-National Labour 101

XXI. Raw Materials 106

XXII. Metaphors 115

XXIII. Conclusion 119

SECOND SERIES

CHAPTER

I. Natural History of Spoliation 124

II. Two Systems of Morals 140

III. The Two Hatchets 147

IV. Lower Council of Labour 151

V. Dearness-Cheapness 154

VI. To Artisans and Workmen 163

VII. A Chinese Story 171

VIII. Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc 175

IX. The Premium Theft 177

X. The Taxgatherer 185

XI. Protection; or, The Three City Aldermen 191

XII. Something Else 201

XllI. The Little Arsenal of the Free-Trader 210

XIV. The Right Hand and the Left 216

XV. Domination by Labour 222

Publisher's Statement ↩

The reason for republishing Bastiat's "Economic Sophisms" (which we have called "Social Fallacies") is that we believe Bastiat shows the fallacy of government planning better than any other writer of any period. Since he wrote a century ago, his work cannot be regarded as party-policies now. It deals with fundamental principles of political economy which out-last all parties.

It has been claimed that Bastiat was the first person who ever wrote on economic questions interestingly, clearly and entertainingly enough so that his writings did not need to be subsidized. It will be remembered that the Duke of Buccleuch financed Adam Smith's works. Other patrons financed the works of John Stuart Mill. Bastiat, however, wrote so clearly and so wittily that he was able to sell enough books to make a profit.

As Bastiat said in his "Harmonies of Political Economy," the companion work to his "Sophisms:"

"There is a leading idea which runs through the whole of this work, which pervades and animates every page and every line of it; and that idea is embodied in the opening words of the Christian Creed, - I believe in God."

Bastiat did not have an orthodox conception of God, judging from his writings. He believed God was order, law, liberty, truth, immutable principles, a natural constitution.

As he remarks, "If this work differs from the writings of the Socialists, it is in this, that the latter say, 'We pretend to believe in God, but in reality we believe only in ourselves; seeing that we have no faith in the maxim, laissez faire, and that we all give forth our social nostrums as infinitely superior to the plans of Providence.'

"For my part, I say, laissez faire; in other words, respect liberty, and the human initiative, ... because I believe that it is under the direction of a superior impulse, because, Providence being unable to act in the social order except through the intervention of men's interests and men's wills, it is [2] impossible that the natural resulting force of these interests, the common tendency of these wills, should be towards ultimate evil; for then we must conclude that it is not only man, or the human race, which proceeds onward towards error; but that God himself, being powerless or malevolent, urges on to evil His abortive creation. We believe, then, in liberty, because we believe in universal harmony, because we believe in God."

Again, he remarks, "It would be absurd in the atheist to say, laissez faire le hasard! - seek not to control chance, or blind destiny. But, as believers, we have a right to say, seek not to control the order and justice of God - seek not to control the free action of the sovereign and infallible mover of all, or of that machinery of transmission which we call the human initiative. Liberty thus understood is no longer the anarchical deification of individualism. What we adore is above and beyond man who struggles; it is God who leads him."

"Social Fallacies" or "Economic Sophisms" is a reprint from Bastiat's "Fallacies of Protection," translated by Patrick James Stirling and printed in 1909 by Cassell and Company, Ltd., London; and his "Political Economy," translated from the Paris edition of 1863 and printed in 1869 by The Western News Company, Chicago.

In Bastiat's "Political Economy," above referred to, Mr. Macleod is quoted as saying Bastiat's definition of Value is "the greatest revolution that has been effected in any science since the days of Galileo." His definition of Value is different from that of Adam Smith or Ricardo. It leads neither to belief in single tax nor to socialism, but leads to freedom and an ever-increasing standard of living.

The Foreword written by Rose Wilder Lane shows her keen insight into the importance of freedom, as one would expect from the author of "Give Me Liberty," and "The Discovery of Freedom," published by The John Day Company, New York.

"Harmonies of Political Economy" also will be republished in two separate volumes.

May 30, 1944

Register Publishing Co., Ltd.

Santa Ana, California

[3]

FOREWORD By ROSE WILDER LANE ↩

Frederic Bastiat is one of the leaders of the revolution whose work and fame,

like Aristotle's, belong to the ages. Aristotle, too, was a pioneer in an unexplored

continent of human knowledge; he did little more than blaze two trees where

the Wilderness Road began; he showed the way to a new world that he did not

reach. What modern science owes to Aristotle, a free world will someday owe

to Bastiat.

He was born in Bayonne on June 29, 1801, when France was rocking under the

first impact of the revolution upon the Old World. Tutored by Washington and

advised by Jefferson, Lafayette had brought the revolution from America to

Europe.

The reaction against it was swift and terrible; in France, the Terror, from France, Napoleon. In England the reaction against liberty revoked the liberties that had been granted to Englishmen; free speech, free assembly, trial by jury, habeas corpus, all were taken back; there was a cold Terror in England.

Bastiat's father was a merchant, hardly surviving through perilous times. As a schoolboy, Frederic heard of Napoleon's retreat from Moscow, the defeat at Waterloo. He was fourteen when the Emperor was exiled to St. Helena, and Russia moved into Europe to restore autocracy.

Three years later, the boy went to work in his uncle's counting house. He spent six years there, learning the difficulties of mechandising (sic). Then he inherited his grandfather's little farm at Mugron and became a farmer.

Temporarily checked in Europe, the revolution was carried southward from its source in the American Republic. Bolivar and San Martin were liberating half a hemisphere. From the Rio Grande to Montevideo, liberals inspired by (and from) the great constitutional Republic in the north were trying to establish human rights throughout South America. They, too, set up Republics modeled upon the first; like the French, they tried and failed, and tried again. The news of their successes and defeats came [4] late, from far away, to a farmer in Mugron. Bastiat tended his vines and his small fields, and thought. In the evenings he re-read a few books, and thought.

The revolution had shattered the old bases of thought. Europeans were beginning the attempt, not yet abandoned, to combine the new idea that men are free with the ancient belief that men are not free. The attempt to do this always encounters itself coming back from the opposite direction. The King of France was liberal and reactionary; the French royalists were liberals, the French republicans were imperialists. Political action was stymied.

In a constitutional monarchy with elective representation, the King re-established primogeniture, the basis of feudalism. By a "law of liberty and love," parliament suppressed free press. An "election of anger and vengeance" reacted against that by electing socialists. Polignac's effort to restore Divine Right failed. The King arbitrarily dismissed the Chamber of Deputies, denied tradesmen a right to hold political office, and clamped down a censorship. And suddenly the people of Paris rose and fought.

During three bloody days, the "Glorious" July Days, while ragged, hungry men and women fought the troops at the barricades, and killed and died in the narrow streets, Lafayette decided the issue. He joined the group of Republican Imperialists, and they offered the throne of France to Louis Phillipe, son of the Duc D'Orleans, returned from his home in Gallipolis, Ohio.

They offered him the throne on these conditions: relinquish the King's superiority

to law; abolish hereditary succession in the House of Peers; admit the responsibility

of Cabinet Ministers in government; acknowledge the people as the source of

power, and widen the franchise; grant freedom of the press and of religion.

Louis Phillipe accepted the terms. The White flag of the Bourbons came down

again, and again the American colors, the red, white and blue of liberty, rose

as the flag of France.

In Mugron, Frederic Bastiat grasped the opportunity. He was twenty nine years

old in that July of 1830, and at last he could work for freedom. In 1831 he

was juge de paix in his canton; in 1832 he was a member of the conseil general

of the [5] Landes; in 1834 he published his first pamphlet on practical taxation.

Thereafter he did the work of two men, as active politician and as thinker

and writer.

To understand his importance, one must glance at the mid-19th century.

Americans had begun the world revolution half a century earlier. The outward

revolutionary impulse had disrupted Europe and overthrown every government

south of the Rio Grande. Excepting Great Britain's hold on Canada and Spain's

on Cuba,

it had driven the Old World from the western hemisphere. Now the outward impulse

temporarily slackened. In the revolution's center, the States were straining

against their union. Northern manufacturers were increasing the Federal power

and using it to re-establish a fragment of King George's planned economy, his "protective" tariff;

southern agriculturists were revolting against this reaction. American thinkers

were succumbing to the European confusion of thought. The realistic, rational

thinking of Madison and John Adams was replaced by Emerson's trancendentalism,

infused with the first infiltration of socialism from Europe.

After the defeat of Napoleon, the Terror in England slowly waned. British subjects were granted their former rights again, and in addition a cautious freedom of the press. The planned economy was still operating as police-enforced economic regulations always work; it was starving the English working classes and hampering British shipping and trade. A struggle for freedom began again where it always begins, among merchants and traders. They demanded, and got, repeal of the Corn Laws that kept food out of England, repeal of the regulations and the tariffs that strangled shipping and commerce. Their struggle was the British liberal movement which made Victorian England's prosperity and empire.

But the British liberals, too, attempted the impossible combination of the knowledge that men are free with the belief that men are not free. They acted practically, they demolished the political obstacles to free action and free trade, but they acted as individualists and spoke as socialists. For this reason, the British liberating movement was short lived, and slid backward into socialism.

[6]

Bastiat is the thinker who carried the revolution into economics. The American

revolutionists had been the first to "trace civil government to its foundations

in the moral and physical nature of man," as John Quincy Adams said. They

carried the

Jewish-Christian doctrine of man's free will, of individual self-control and

responsibility, into political philosophy, and used it as a political principle.

Bastiat traced economics to its foundation in the moral and physical nature

of man, and of man's eternal situation on this earth. Bastiat's thinking uses

the prin•ciple of man's natural liberty as an economic principle.

In Bastiat's books, therefore, the reader finds the first rational analysis of a free economy. He laid the groundwork of the thinking that American economists should have been doing during this past century. He outlines, in economic philosophy, the modern world that capitalism has actually created during the ninety years since he died.

The brilliance and accuracy of his thinking is indicated in one small detail. In a footnote to Economic Harmonies - a fragment of the great work he did not complete - he gives the simple mathematical formula of the increase and distribution of wealth in a free economy. The formula is pure theory; Bastiat arrived at it rationally, in 1840. In 1930, the United States Census report confirmed it.

In 1840, when Bastiat wrote, the national income of these United States was 2 billion dollars; capitalists and landlords got 60 %, the employed got less than 40 %. Ninety years later, the national income was 75 billion dollars; wage-earners got 64%, entrepreneurs about 20%, capitalists and landlords, 16%. For ninety years, the American capitalist economy had followed Bastiat's mathematical formula of the increase of wealth, and of the transfer of wealth from capitalist to wage-earner.

Bastiat was also the first to see clearly that the enemy of freedom was socialism. In America, the intellectuals were blindly adopting socialism from Europe. Bastiat lived in Europe, where the enemy still seemed to be the Kings; he wrote twenty years before Marx, but he saw in Fourier the seed of the reaction that has grown from Fourier and Hegel, through Marx, to Stalin, Mussolini, and Hitler. He saw the "common good" fallacy, [7] and pointed it out in Bright, and Adam Smith.

His labors were prodigious. He organized the first French Free Trade association,

and acted as secretary of its central committee in Paris; he organized its

branch societies; he interviewed politicians, collected funds, edited a weekly

journal, contributed to four other journals, addressed meetings in Paris and

throughout France, delivered courses of lectures on the principles of political

economy to '

students in the colleges of law. He was dying of tuberculosis.

The socialist-communist theories were already too strong to be overcome. The struggle against them was abruptly suppressed in February, 1848, when Louis Napoleon seized power in France, by the Nazi methods which Victor Hugo describes vividly in THE HISTORY OF A CRIME. The French democracy applauded the crime and confirmed Louis Napoleon's empire by an overwhelming majority vote, as a German democracy was to applaud and confirm Hitler a century later.

Under Louis Napoleon, a French national socialism was temporarily supreme. Not for long. The revolution has not yet been won in France, but it has not ceased since Jefferson advised Lafayette, "Have the King call an assembly of the States General." Since then, three generations of Frenchmen have set up three French Republics, and lost them to a Terror, a Directory, two Empires, one Commune, and the dictatorship of Marshall Petain.

Exhausted by overwork, and robbed of his voice by the death in his body, Bastiat continued to write. For two years he poured out a succession of brilliant pamphlets. He planned a great constructive work, which would base the science of economics firmly on the principle of individual freedom and human rights, and show conclusively that individual economic interests, "Left to themselves, tend to the progressive preponderance of the general welfare." He lived to publish a fragmentary first volume of that work, Les Harmonies economiques.

He died in Rome on December 24, 1850. Not a century ago, he died of tuberculosis, a disease of malnutrition, in a world only beginning to know that sickness is not the will of God which man can not conquer, a world that knew that hunger was [8] constant and some starvation always inevitable, but had never heard of malnutrition nor imagined dietetics.

Bastiat's brilliant ECONOMIC SOPHISMS first appeared as a series of articles that he contributed to the Journal des Economistes in 1844. They attracted attention throughout Europe, and placed Bastiat at once among the important economists of the century. His work, with Madison's and Jefferson's, has been obscured during the reactionary period which came from Fourier's ideas and Hegel's, through Marx, directly to Bismarck's Prussian national socialism of the 1880's, and through Marx's First International directly to communism in Russia, fascism in Italy, Hitler's national socialism in Germany, and Newdealism in the United States. Only a few Americans have treasured Bastiat's wisdom, and its development in political action is still the task of future American economists.

Now that this reaction is near its end and a genuine liberalism begins to rise again at the source and center of the world revolution for personal freedom and human rights, many Americans will welcome an economist whose thinking is clear, honest, rational and realistic. Bastiat's work is as timely today as it was in the France of Louis Phillipe (sic), for the truth that will prevail has not yet conquered the world, and the delusions that resist it are still unchanged.

Danbury, Connecticut,

April, 1944