Was Molinari a true Anarcho-Capitalist?

(1.) “Was Molinari a true Anarcho-Capitalist?: An Intellectual History of the Private and Competitive Production of Security”. A paper given at the Libertarian Scholars Conference, NYC, 21 Sept. 2019 [Full paper HTML and PDF – Slides – Handout ]. See the abstract of the paper below.

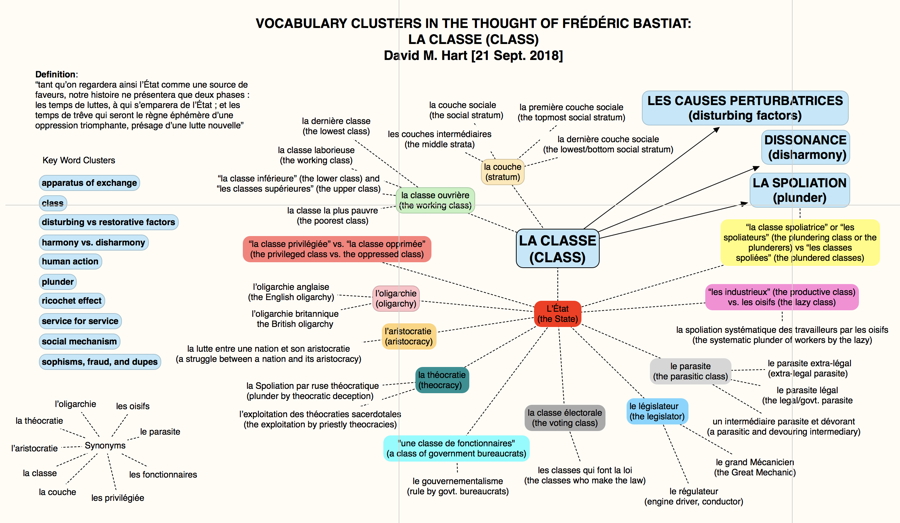

Some Thoughts on an ‘Austrian Theory of Film’: Ideas and Human Action in a Film about Frédéric Bastiat

(2.) “Some Thoughts on an ‘Austrian Theory of Film’: Ideas and Human Action in a Film about Frédéric Bastiat”. A paper given at the Libertarian Scholars Conference, NYC, 21 Sept. 2019. [Full paper in HTML and PDF – Slides ] [ Screenplay – Illustrations ].

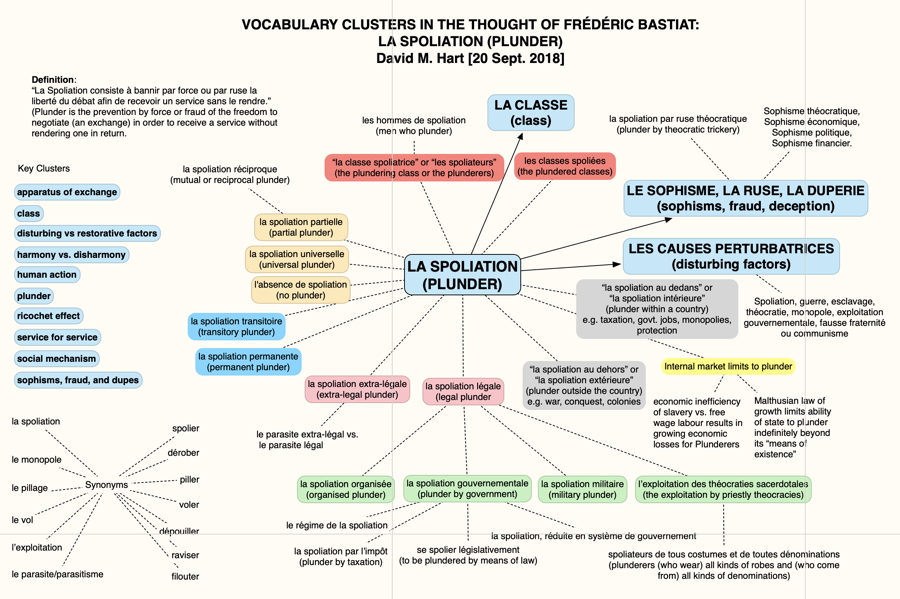

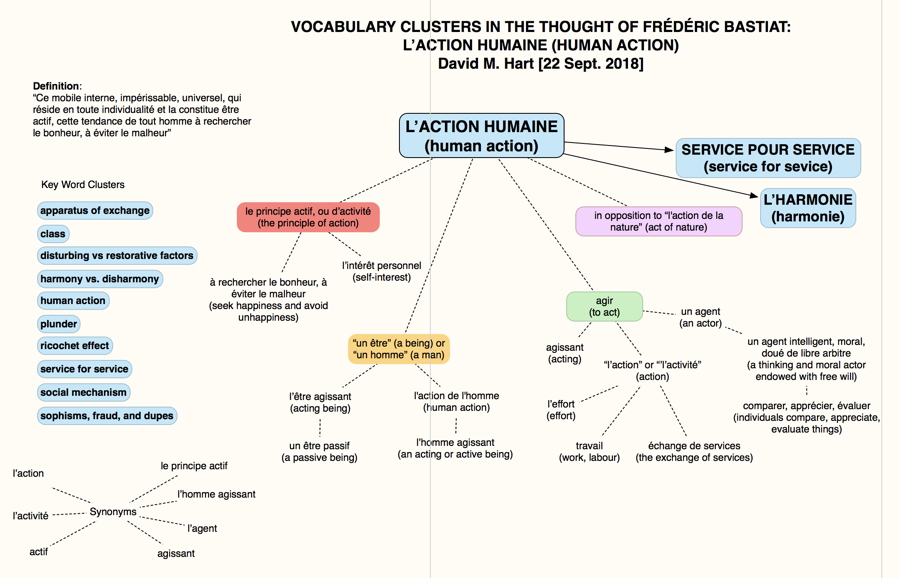

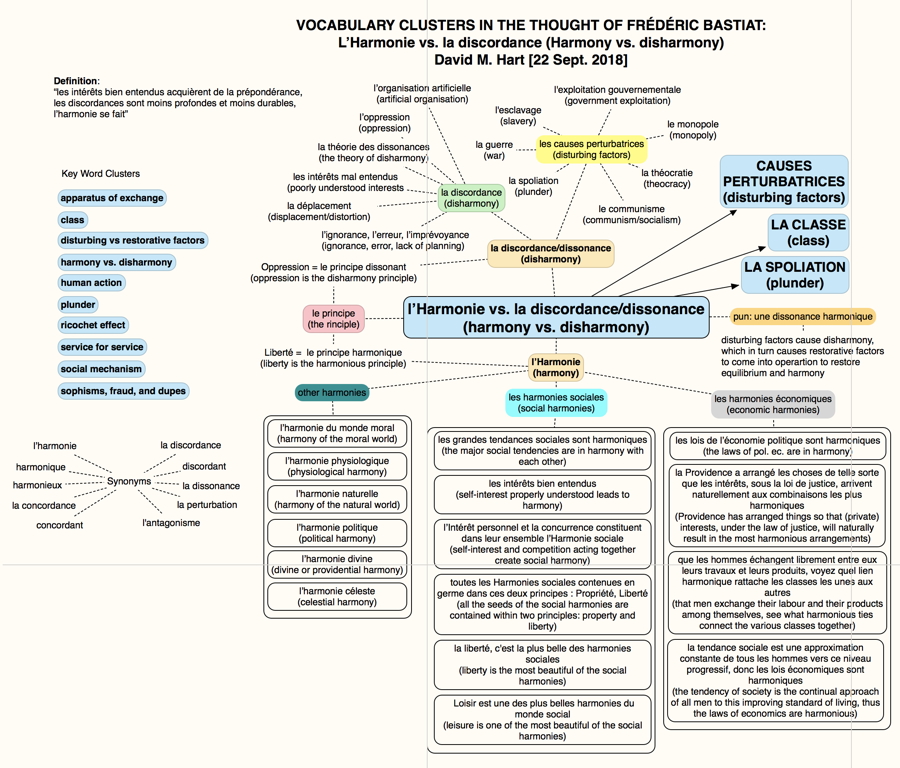

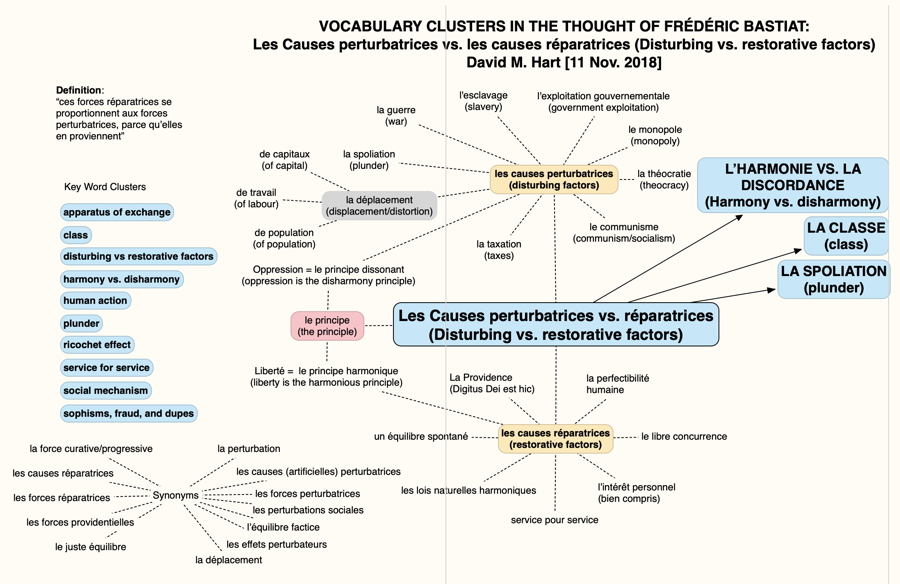

Abstract: When thinking about the problems a filmmaker faces when trying to make a “movie of ideas” I was struck by the relevance of the works of two economists, that of Ludwig von Mises’ theory of “human action” and Frédéric Bastiat’s theory of “the seen and the unseen,” in helping the filmmaker think about the problems of depicting economic ideas and economic actions in a visual medium like film. It made me think that perhaps we should develop an “Austrian theory of Film” to help us do this. If there can be a feminist theory of film and a Marxist theory of film, why not an Austrian theory of film?

Mises is relevant because according to his theory of human action people act upon the ideas they have about what their interests are (in many cases these are economic interests), what their alternatives might be, and how best they can attempt to satisfy those interests given their scarce resources and other options. In essence then, human action is based upon the ideas people hold. Bastiat is relevant because the ideas people hold in their heads are a textbook example of what is invisible to outsiders, in other words they are “the unseen” perhaps even the unseeable, yet the actions which people take based upon the ideas they have about themselves, their interests, and the world around them can be “seen” in the actions they take.

A few questions I pose and attempt to answer are: can the filmmaker use these theories about economic behavior to make an interesting film with economic themes? can the ordinary film viewer correctly infer the ideas which lie behind a person’s choices and actions as depicted in a film? and how subtle should a screenplay writer or director be in giving the viewer hints (or what I cake visual “nudging”)? I use the screenplay I have have written about Bastiat’s activities during the revolution of 1848 and the Second Republic, called “Broken Windows”, to discuss these and other matters. See the screenplay, “Broken Windows” and the accompanying “illustrated essay” of the life and times of Bastiat.