Bastiat’s Theory of Class: The Plunderers vs. the Plundered.”

This is the Introductory Essay for a bi-lingual edition of Frédéric Bastiat’s writings on class and plunder which is in preparation. It is an attempt to reconstruct from his scattered writings on class the History of Plunder he planned to write but never did. The anthology of around 15 texts is in an early stage of editing and will be added later. See here for details.

Introduction

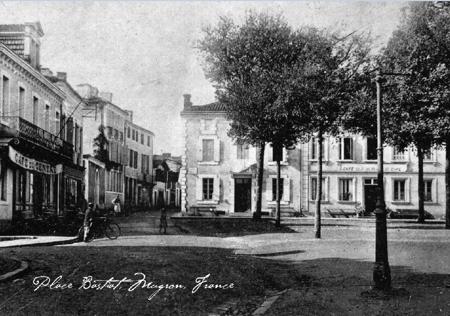

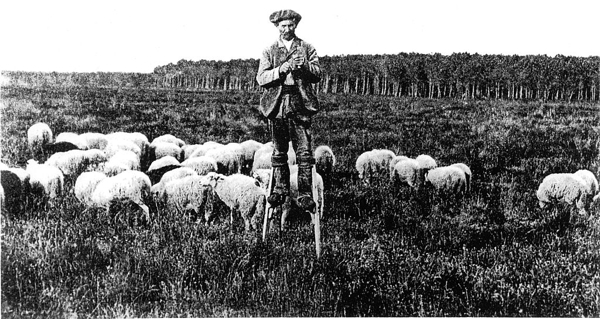

Frédéric Bastiat’s unwritten “History of Plunder” ranks alongside Lord Acton’s never written (and possibly unwritable) “History of Liberty” and Murray Rothbard’s third volume of his “History of Economic Thought” series as one of the greatest libertarian books never written. Had he lived to a ripe old age, instead of dying at the age of 49 from throat cancer, he might have finished his magnum opus Economic Harmonies and lived to complete his history of plunder. It should be noted that Karl Marx, the founder of Marxism, published the first volume of his magnum opus, Das Capital (1867), when he too was 49 years old but lived another 15 years during which time he wrote but never completed another two large volumes. Given the chance, Bastiat might well have fulfilled his great promise as an economic theorist and historian and have become the Karl Marx of the 19th century classical liberal movement. How history might have been different if he had! Or maybe not, who can tell?

In the 8 years Bastiat was active as a writer and a politician (1843-1850) he produced six large volumes of letters, pamphlets, articles, and books which Liberty Fund is translating as part of its Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat (2011-2015). What emerges from a chronological examination of his writings is his gradual realization that the State is a vast machine which is purposely designed to take the property of some people without their consent and to transfer it to other people. The word which he uses with increasing frequency in this period to describe the actions of the State is “la spoliation” (plunder), although he also uses words like “parasite”, “viol” (rape), “vol” (theft), and “pillage” which are equally harsh and to the point. In his scattered writings on State plunder written before the 1848 Revolution he identifies the particular groups which have had access to State power at different times in history in order to plunder ordinary people, these were warriors, slave owners, the Catholic Church, and more recently commercial and industrial monopolists. Each of these groups and the particular way in which they used State power to exploit ordinary people for their own benefit were to have a separate section in his planned “History of Plunder.” Were he to have defined the State before the 1848 Revolution it might well have been along these lines: “The state is the mechanism by which a small privileged group of people live at the expense of everyone else.”

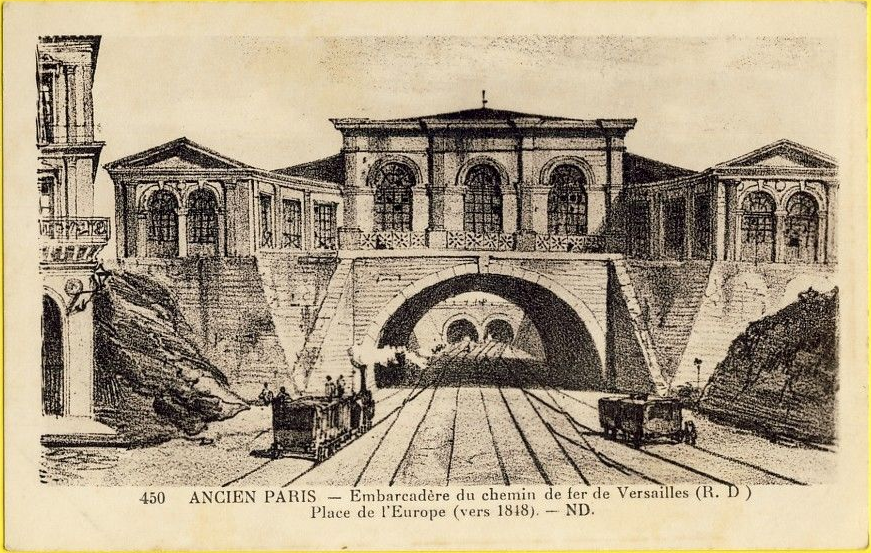

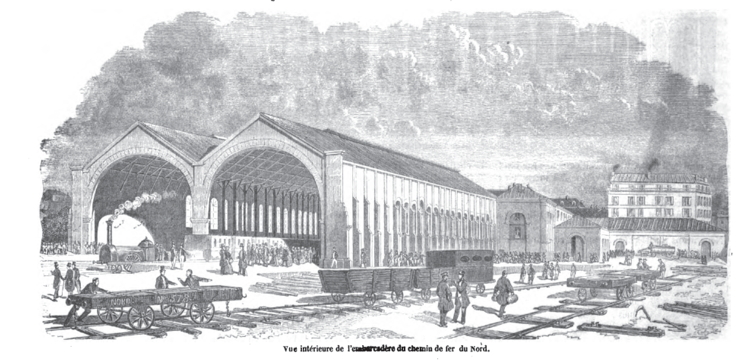

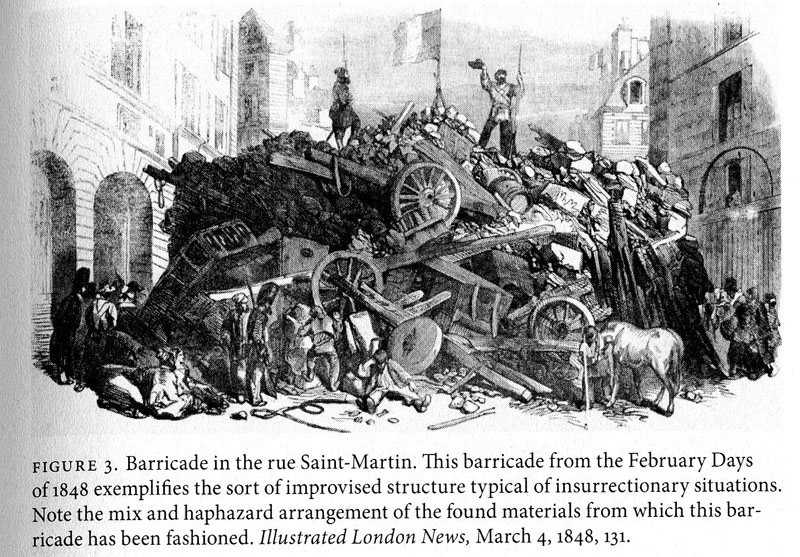

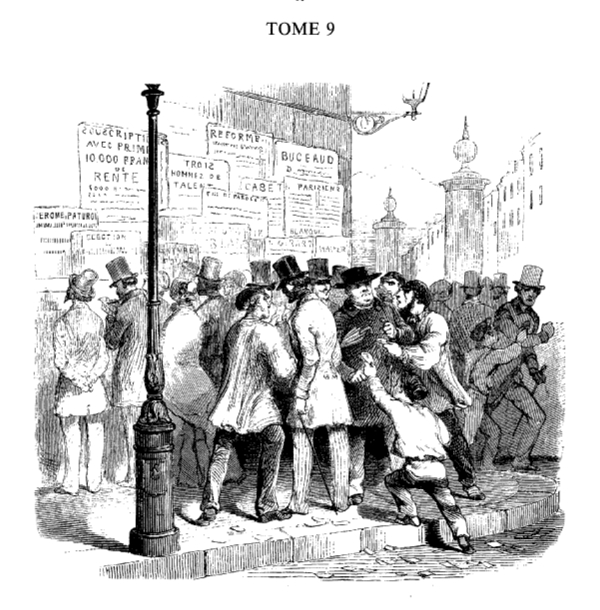

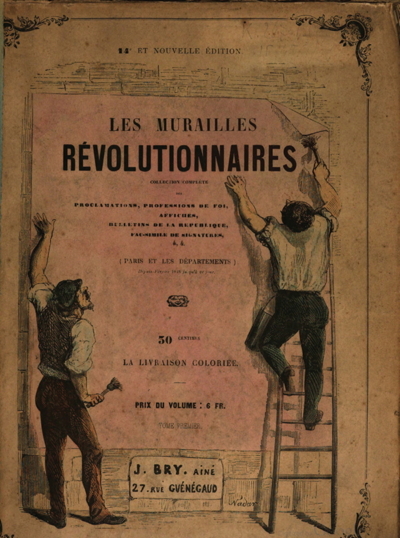

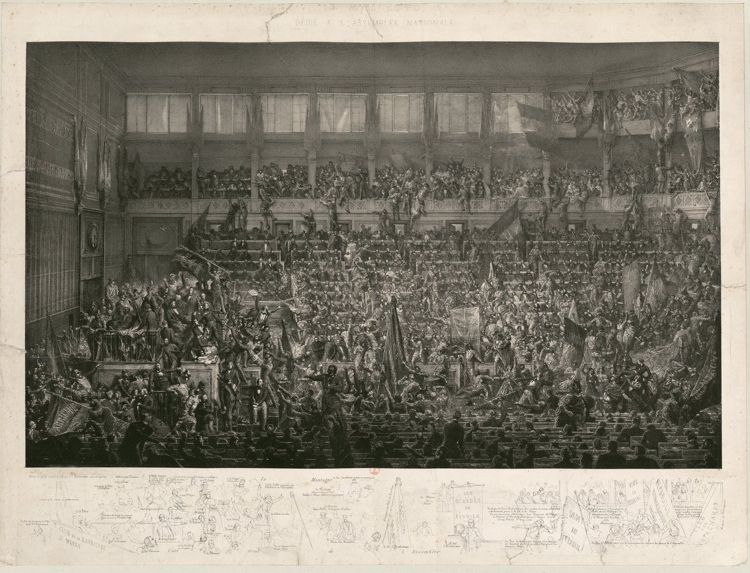

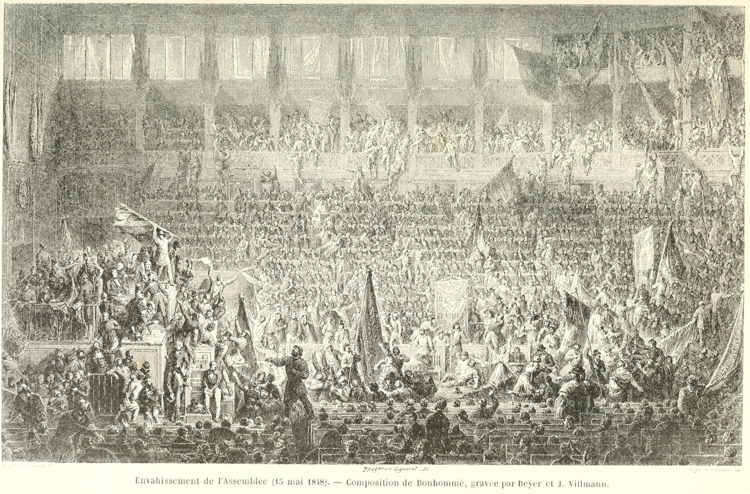

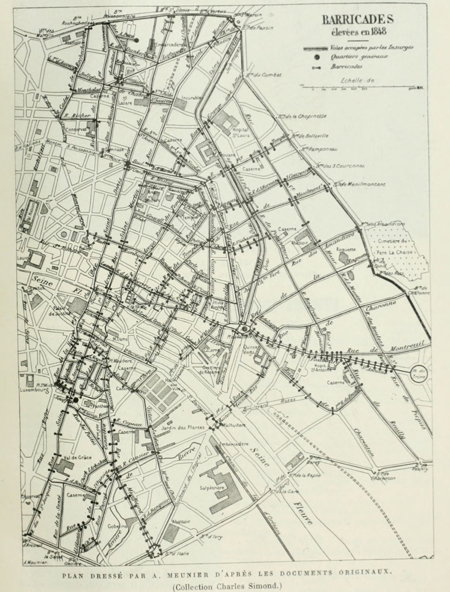

But the outbreak of Revolution in February 1848 in Paris changed the equation dramatically which forced Bastiat to change his analysis of plunder and the State. Before the Revolution, small privileged minorities were able to seize control of the State and plunder the majority of the people for their own benefit – what he termed “la spoliation partielle” (partial plunder). For example, slave owners were able to exploit their slaves, aristocratic landowners were able to exploit their serfs, privileged monopolists were able to exploit their customers, and thus it made some kind of brutal sense for a small minority to plunder and loot the majority. In Bastiat’s theory before 1848 he identified the special interests who benefited from their access to the State and exposed them to the public via his journalism, often with withering criticism and satire, such as the landed elites who benefited from tariff protection, the industrial elites who benefited from monopolies and state subsidies, and the monarchy and the aristocratic elites who benefited from access to jobs in the government and the army.

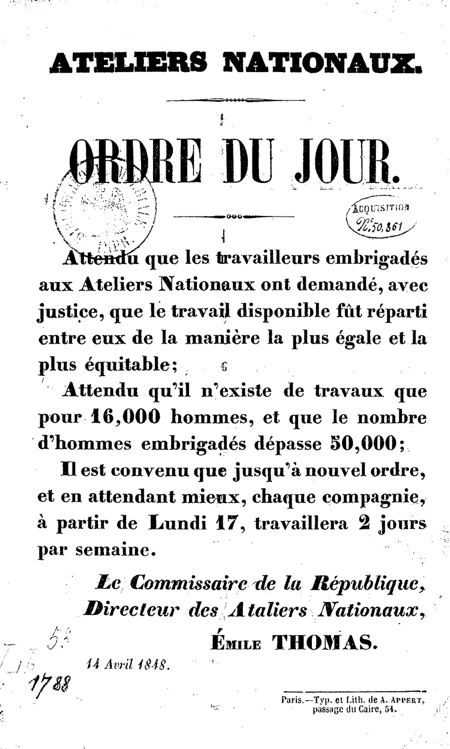

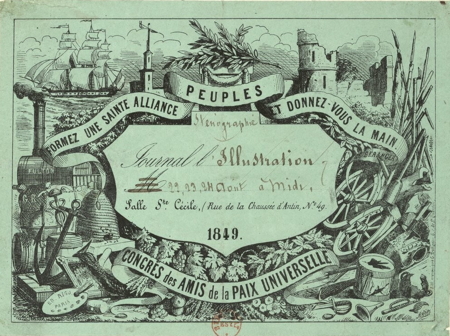

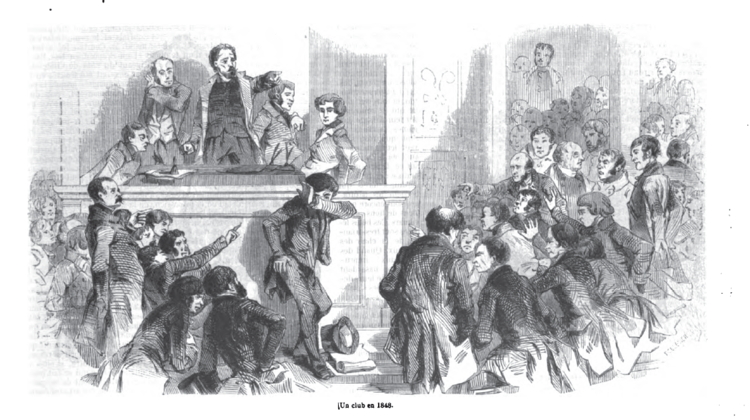

The rise to power of socialist groups in 1848 meant that larger groups, perhaps a majority of the voters if the socialist groups were successful in winning office, were now trying to use the same methods used by these privileged minorities but now for the benefit of “everyone” instead of a narrow elite – or, what he termed “la spoliation universelle” (universal plunder) or “la spoliation réciproque” (reciprocal plunder). The problem as Bastiat saw it, was that it was theoretically and practically impossible for the majority to live at the expense of the majority. Somebody had eventually to pay the bills and the majority could not do this if it was paying the taxes as well as receiving the “benefits” of state handouts, with the State and its employees (les fonctionnaires) taking its customary cut along the way. This conundrum led him to put forward his famous definition of the State in mid-1848: “L’État, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde” (The state is the great fiction by which everyone endeavours to live at the expense of everyone else.)[2] Bastiat’s political strategy now had to change to trying to convince ordinary workers that promises of government jobs, state-funded unemployment relief, and price controls were self-defeating and ultimately impossible to achieve.

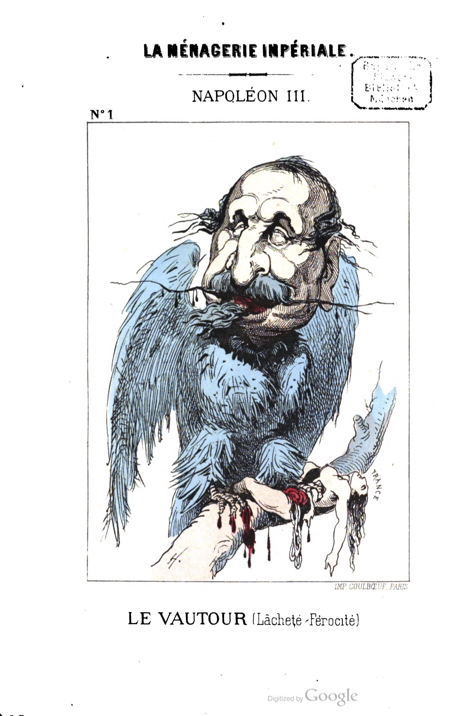

Bastiat was not able to win this intellectual or political debate because of his death in December 1850 and the socialist forces were ultimately defeated temporarily by a combination of military and police oppression as the “Party of Order” supported the rise of Louis Napoleon who quickly designated himself as the “Prince-President” of France and then appointed himself Emperor Napoleon III. However, the core weakness of the welfare state was clearly identified by Bastiat in 1848 and we continue to see the consequences of its economic contradictions and possible collapse in the present day.

With this broader picture in mind I would like to examine Bastiat’s theory of plunder and the class analysis which he developed from this, so we can see more clearly what he had in mind and appreciate the power of his analysis.

The Texts for the Anthology

Unfortunately, Bastiat’s ideas remain scattered throughout many of his essays and articles which were written between 1845 and 1850. The most important of these works (some 15 in number) where he provides more extensive discussion of the nature of class and plunder are the following (listed in chronological order), 6 of which come from the Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848), 2 from Economic Harmonies (1850, 1851), and 2 from What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850):

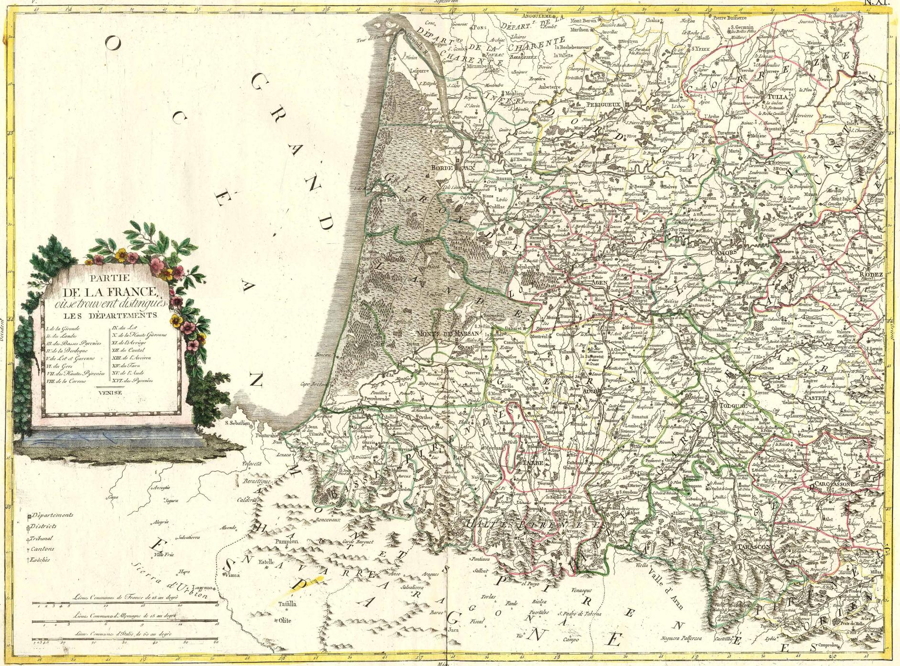

- the “Introduction” to Cobden and the League (July 1845), in which he discusses the English “oligarchy” which benefited from the system of tariffs which Cobden and his Anti-Corn Law League were trying to get repealed; the strategy they adopted was to identify the key source of income for the ruling oligarchy (tariffs on imported food) and to eliminate it (by opening the economy to free trade) and thus weaken the oligarchy’s political and economic power

- ES1 “Conclusion” to Economic Sophisms 1 (dated November 1845), where he reflects on the use of force throughout history to oppress the majority, and the part played by “sophistry” (ideology and false economic thinking) to justify this

- ES2 9 “Theft by Subsidy” (JDE, January 1846), where he insists on the need to use “harsh language” – like the word “theft” – to describe the policies of governments which give benefits to some at the expence of others[4]

- ES3 6 “The People and the Bourgeoisie” (LE, 23 May 1847), in which he rejects the idea that there is an inevitable antagonism (“la guerre sociale” (war between social groups or classes)) between the people and the bourgeoisie, while there is one between the people and the aristocracy; he also introduces the idea of “la classe électorale” (the electoral classe) which controls the French state by severely limiting the right to vote to the top 1 or 2% of the population

- ES2 1 “The Physiology of Plunder” (c. 1847), which is his first detailed discussion of the nature of plunder (which is contrasted with “production”) and his historical progression of stages through which plunder has evolved from war, slavery, theocracy, and monopoly

- ES2 2 “Two Moral Philosophies” (c. 1847), where he distinguishes between religious moral philosophy, which attempts to persuade the men who live by plundering others (e.g. slave owners and protectionists) to voluntarily refrain from doing so, and economic moral philosophy, which speaks to the victims of plundering and urges them to resist by understanding the true nature of their oppression and making it “increasingly difficult and dangerous” for their oppressors to continue exploiting them

- ES3 14 “Anglomania, Anglophobia” (c. 1847), where he discusses “the great conflict between democracy and aristocracy, between common law and privilege” and how this class conflict is playing out in England; it is a continuation of his analysis of the British “oligarchy” which he began in the Introduction to Cobden and the League.

- “Justice and Fraternity” (15 June 1848, JDE), where Bastiat first used the terms“la spoliation extra-légale” (extra-legal plunder) and “la spoliation légale” (legal plunder); he describes the socialist state as “un intermédiaire parasite et dévorant” (a parasitic and devouring intermediary) which embodies “la Spoliation organisée” (organised plunder)

- “Property and Plunder” (JDD, 24 July 1848), in the “Fifth Letter” Bastiat talks about how transitory plunder gradually became “la spoliation permanente” (permanent plunder) when it became organised and entrenched by the state

- the “Conclusion” to the first edition of Economic Harmonies (late 1849), where he sketches what his unfinished book should have included, such as the opposite of the factors leading to “harmony”, namely “les dissonances sociales” (the social disharmonies) such as plunder and oppression; or what he also calls “les causes perturbatrices” (disturbing factors); here he concentrates on theocratic and protectionist plunder

- “Plunder and Law” (JDE, 15 May 1850), where he addresses the protectionists who have turned the law into a “sword” or “un instrument de Spoliation” (a tool of plunder) which the socialists will take advantage of when they get the political opportunity to do so

- “The Law” (June 1850), Bastiat’s most extended treatment of the natural law basis of property and how it has been “perverted” by the plunderers who have seized control of the state, where the “la loi a pris le caractère spoliateur” (the law has taken on the character of the plunderer); there is a longer discussion of “legal plunder”; and he reminds the protectionists that the system of exploitation they had created before 1848 has been taken over, first by the socialists and soon by the Bonapartists, to be used for their purposes thus creating a new form of plundering by a new kind of class rule by “gouvernementalisme” (government bureaucrats)

- WSWNS Chap. 3 “Taxes” (July 1850), on the conflict between the tax payers and the payment of civil servants’ salaries whom he likens to so many thieves, who provide no (or very little) benefit in return for the money they receive, and thus create a form of “legal parasitism”

- WSWNS Chap. 6 “The Middlemen” (July 1850), where he describes the government’s provision of some services as a form of “dreadful parasitism”

- Economic Harmonies, part 2, chapter 17, “Private Services, Pubic Services” (published posthumously in 1851), an examination of the extent to which “public services” are productive or plunderous; he discusses how in the modern era “la spoliation par l’impôt s’exerce sur une immense échelle” (plunder by means of taxation is excercised to a high degree), but rejects the idea that they are plunderous “par essence” (by their very nature); beyond a very small number of limited activities (such as public security, managing public property) the actions of the state are “autant d’instruments d’oppression et de spoliation légales” (only so many tools of oppression and legal plunder); he warns of the danger of the state serving the private interests of “les fonctionnaires” (state functionaries) who become plunderers in their own right; the plundered class is deceived by sophistry into thinking that that they will benefit from whatever the plundering classes seize as a result of the “ricochet” or trickle down effect as they spend their ill-gotten gains.