See my earlier posts:

- The Presumption of Government Failure | Reflections on Liberty and Power (1 Jan. 2021)

- What is to be Done? The Rise of Hygiene Socialism and the Prospects for Liberty (2 December, 2020)

- The Work of Sisyphus: the Urgent Need for Intellectual Change (25 April, 2020)]

[Collapsed Building, Bangladesh (Apr. 20213)]

1.) The Collapse of the Liberty Movement in Australia and Elsewhere in 2020

What we have witnessed during 2020 in Australia and probably in the UK and US as well, was the catastrophic collapse and failure of the liberty movement in the face of the Covid hysteria and panic, and the lockdown socialism which has been the result (or in the case of the state of Victoria “lockdown stalinism”). We haven’t seen anything like such an expansion of government power and intervention in the Australian economy since the mid-1970s, and I fear 2021 will continue down this path with barely a squeak of protest.

In 1972 the social democratic Labor Party came to power and in the space of three years completely transformed the Australian economy, including the introduction of a country-wide single payer health care system, huge increases in taxation, and in government debt. That is the reason why I first became active in libertarian politics and I joined many thousands of people who were appalled and outraged at what was happening. Last year, a conservative government did more in 10 months to expand the power of the state, increase debt, and drastically cut private economic activity than three years of a “socialist” government back in the 1970s.

Yet where are all those who once could be relied on to speak out and stand up for liberty? They are all lying low and saying and doing nothing.

Something very similar has happened in the UK and has been recognized by an interesting post on the Lockdown Skeptics website looking back on the anniversary of the first lockdowns in March 2020. See “The First Anniversary of “Three Weeks to Flatten the Curve”” Lockdown Sceptics (23 March 2021) article

It is hard to know what to do in the face of this. Is it “betrayal” of our ideals? cowardice? the failure of their critical faculties, on many levels, to question the dictates of politicians and the so-called advice of technocrats? Have they forgotten all the economics they once knew? Have they stopped loving liberty? Have they become “willing slaves”? Who knows.

2.) Some Reasons for Optimism 50 Years ago

When I look back over my working life things seemed to be more hopeful back in the 1970s and 1980s than they seem today. In 1974 I was at high school in Sydney at the time and had just discovered libertarianism the year before. My path was not unusual – Rand, then Rothbard, then Mises and Hayek. Toss in Lysander Spooner and Bastiat as well for good measure.

At that time, there were reasons for some optimism: Hayek won the Nobel Prize in 1974; Friedman in 1976; Nozick had published Anarchy, State, and Utopia to much acclaim; Rothbard had published a best seller with a mainstream publisher For a New Liberty. A couple of years later Thatcher became PM (1979) followed by Ronald Reagan in 1981; Roger Douglas was Minister of Finance in NZ in 1984 and began deregulating its economy. . Free market ideas were even beginning to appear in popular culture with Friedman’s “Free to Choose” in 1980 and “Yes, Minister” (1981). This was all topped off with the coming down of “The Wall” in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union. It seemed we were on a roll and victory might be seen, admittedly at the end of a still very long tunnel.

On a personal note I was living in Stanford when Reagan was President, and then in Cambridge when Thatcher was in power, so I was able to witness what was going on first hand. But that is another story.

But then progress in our direction stopped and everything thing seemed to unravel during the 1990s. Instead of cutting back on military expenditure and using the savings to begin winding back the welfare state the neo-cons got control of the US and pushed it in the opposite direction. So I see the 1990s as the “lost decade” for libertarianism. When 9/11 occurred the stage was set for what turned out to be 2 decades of the expansion of state power, not its winding back. I thought in 2001 that the US was “only one crisis” away from full fascism. In 2020 that new crisis might well have come. The people are afraid and they automatically turn to the state for help.

3.) The Willing Slavery of everybody around us today

Watching the craven way in which people just surrendered all their liberties without a fight or even a peep of protest in 2020 made me go back to Étienne de la Boétie’s great essay “Discourse of Voluntary Servitude” (c. 1550s) in order to understand better why this was happening. I started putting different versions of the essay online in English and French. See the Boetie index page His conclusion was that most people accepted the fact of and necessity for being “willing slaves” as a result of custom, education, and ultimately the threat of force. A very few had “a love of liberty” in their hearts which couldn’t be extinguished and struggled against this servitude. The frustrating thing is that he also realized that if enough people just said “no” to the state it would crumble. The problem was to figure out how to fan the spark of the love of liberty in those that had it into a stronger flame, as well as the bigger problem of creating a tiny spark in those who did not already have it. That too is our perennial problem and it has just got much, much worse.

4.) Rethinking the Strategy to achieve Liberty

In Nov. 2020 I also went back to the various papers I had on libertarian strategy going back to Rothbard’s seminal paper) “Toward a Strategy for Libertarian Social Change” (April, 1977) which I put online in a new clean copy (I had an old one there for over a decade but nobody paid any attention to it). I also got hold of several others papers from a conference on strategy which Koch and Rothbard organized in 1976 at the time of the founding of the Libertarian Party and the Cato Institute. These are very interesting and are not readily available. I wanted to provoke a more serious discussion of strategy given the current dire circumstances. See these papers here.

I started getting interested again in strategy back in 2015 when I began writing a few papers and we organised a Liberty Matters discussion on the spread of CL ideas. I wrote even more position papers when Liberty Fund was going through its “Strategic Refresh” in 2018 but these too were all ignored. Some of these are also listed under Nov. 2020 new additions on my website.

5.) The Growing number of Fronts on which we have to fight for liberty

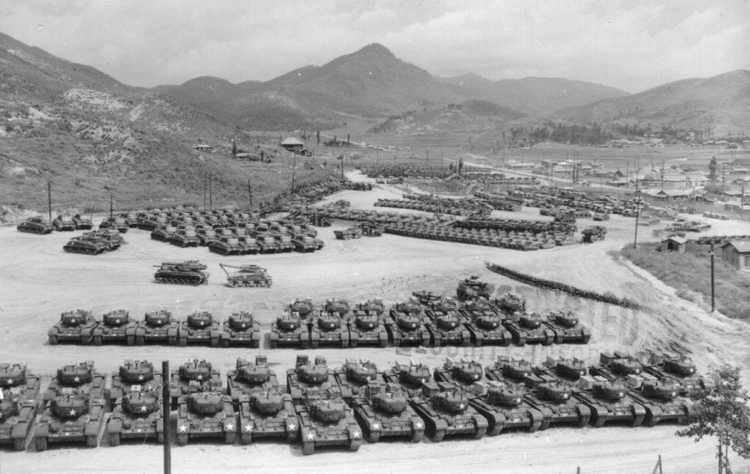

[M46 Patton and M4 Sherman Tanks massed in Korea]

Back in 2010 when Liberty Fund celebrated its 50th anniversary I thought that there was little to celebrate since in the previous 10 years it, along with the other well-funded liberty organizations, seemed to have had no impact in halting some of the greatest new threats to liberty, such as the expansion of wars in the Middle East (now going on for 20 years); the massive and secret surveillance of private emails and phone calls; the restrictions and impediments to plane travel implemented by a massive new bureaucracy; and most recently the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-9 which had seen the almost instantaneous conversion of nearly all economists into Keynesians (if they weren’t already).

It was at this time that I drew up my first list of four major ongoing and new threats to liberty which the liberty movement had failed to address adequately up to 2010. These were:

- War: the expansion of the warfare state following 9/11 and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and its further proliferation in Libya, Syria and elsewhere

- Presidential Power: the growth of presidential power and the abdication of Congress to restrain these powers, such as declaring and financing foreign wars, or ordering the execution of individuals deemed “enemies of the state” without court or congressional oversight

- The Surveillance State: the power of the NSA and other agencies to spy upon and surveil ordinary citizens at will

- Sound Money and Banking: the knee-jerk reversal to Keynesian orthodoxy following the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/9, concerning government debt, deficits, and monetary expansion

I tried to encourage my colleagues to discuss this but they were not interested. They were too busy “celebrating.”

Now 10 years later in 2020 not only have we not been able to counter these four serious threats to liberty, we can add three more to the above list:

- Protectionism: and the use protectionist trade policies under President Trump after 2016

- Socialism: the growth in interest in “socialism” since the 2018 elections; the open self-identification of many politicians as “democratic socialists” is a bad omen

- Radical Environmentalism: the Green movement (e.g. the Green New Deal) has become a powerful force and uses fear of “global warming” as cover for socialism; its impact on the thinking of school age children is very worrying for the the future of liberty

If these seven “pre-existing conditions” (to use a medical metaphor) were not enough to frighten lovers of liberty with the enormous effort and time which countering any one of these threats would require, we now face yet two more additional threats to add to my list:

- Critical Race Theory and Wokeness – which has exploded in the last few years and seems to have taken over all levels of education, but most especially the university sector; I fear that this has progressed to the point where we have lost at least one generation, perhaps two, to pro-liberty ideas

- Hygiene Socialism: the hysteria and panic over a virus which has come about because of the public’s change in their tolerance (and accurate evaluation) of risk, the uncritical acceptance of false mathematical models of the spread of the disease, and belief that government central planning and massive restrictions on individual liberty and economic activity can “halt” the spread of the disease and save more lives than it takes.

It is depressing when one lists these threats to liberty on one page. To switch to a military metaphor, it is hard to know where to begin to fight back on a battle field with so many fronts. Our army is small and theirs is so large and apparently growing in numbers and strength. If we only have scarce resources to fight on one or two fronts, which ones should we focus on? what should we do about the other fronts? can we still fight and win some skirmishes on the margin? what happens about the core or the HQ of the state’s armies? do we have to wait for some crisis or collapse to show people the folly of the old statist ways of doing things? how do we know that something worse won’t replace the current system? have we entered a new “Dark Ages” of liberty which was a fear Pierre Goodrich wrote about in one of the founding memoranda for Liberty Fund which he wrote in the late 1950s?

I was struck by this pessimism of Goodrich when I first read it. One function of the Online Library of Liberty, in the light of this, was to act as a “scriptorum” where dedicated (electronic) monks would copy the great books of liberty for the benefit of future generations , since the current generation had lost interest in and knowledge of these works. It was a very long-term strategy and one Goodrich seriously thought about when LF was founded. I wonder if anybody today is taking a similar long term perspective. And if so, does it really matter given the foes we now face on numerous fronts?

Conclusion

The year 2020 has turned out to be a watershed year in the struggle for liberty. Little did we expect that a corona virus (remember when they called it the “novel” corona virus which meant it was merely the latest of several such viruses we have encountered?) would turn the tables against liberty and the liberty movement so suddenly, so completely, and with so little resistance on the part of the public.

But we need to keep this latest attack on the principles, practices, and institutions of liberty in some historical perspective. I believe that when we do that our plight will appear to be even worse than we have imagined. I say this because this latest expansion of state power (what I have termed “hygiene socialism” or “lockdown socialism”) comes on top of the eight other major areas of expanded state power which have emerged over the last 20 years, which remain largely unchallenged (intellectually) and still intact (politically). Had we been able to make some headway in reducing these other manifestations of state power and intervention, weakening their intellectual justification, persuading voters to exercise their electoral power to elect politicians to begin dismantling key government programs, then we would be in a much better position to tackle head-on this latest manifestation of state power, but because it comes on top on these existing programs, our task has suddenly become much harder.

My great fear is that in order to continue to impose and expand hygiene socialism the state will seek and get enthusiastic public support to use these other, pre-existing programs to do this. This means that the corrupted system of money and banking will be called upon to “fund” programs to support failed businesses, locked-down workers, and drug manufacturers; the extensive system of surveillance of private citizens will be used to “trace” and “monitor” suspected disease carriers (or “ex-disease” carriers); the trade policy of “protection” for domestic industry will be expanded to make sure that “the nation” will be able to manufacture all of its “own” masks and vaccines and not be “dependent” on foreign manufacturers (especially the dreaded “Chinese”), and so on. The result will be an expanding and increasingly interlocked system of government programs and interventions which will be argued is “necessary” in order to secure the “safety of the people” (salus populi). Of course, this notion of “the safety of people” could be vastly expanded to other risks to life and limb which are even greater than covid 19. Once one has started down this slippery slope of statism there is no stopping once a certain momentum has built up.

Given the nine “battle fronts” on which we now have to fight the battle of ideas the big issue as far as I can see is whether or not we can identify the “golden thread” which ties all these different fronts together. If we could pick at that thread and unravel the whole cloth, we might have a chance of reversing the course of the battle. But I don’t know what that thread is. Do you?

[Chinese “Tank Man”]