It is not well known that Bastiat planned to write a multi-volume treatise on “the harmonies” and “the disharmonies” which he observed at work both in the economy and in the broader society which surrounded it. This treatise would have a volume or volumes on the “social harmonies,” the “economic harmonies”, and the various “disharmonies” which disturbed, or prevented from appearing, these social and economic harmonies. The volume on “the disharmonies” would also have included a “history of plunder” where Bastiat would analyze how the practice of plunder (la spoliation) had emerged in Europe and how it evolved into the system of “legal plunder” which existed in his own day.

Sadly, Bastiat was not able to even complete the first part of this ambitious project before he died at the age of 49, probably from throat cancer. What we know as the book Economic Harmonies was only half finished – he himself published a volume with the first 10 chapters in early 1850, and his fiends cobbled together an expanded edition using drafts and sketches of chapters they found among Bastiat’s papers which they published posthumously in mid-1851. The latter is the edition readers today know. He never wrote the volume on the Social Harmonies and left several essays and sketches of his theory and history of plunder.

I discuss the ideas behind this ambitious project and attempt a reconstruction of what it might have looked like (also see the list of chapters below), had he been able to finish it, in a new “paper” on “Bastiat on Harmony and Disharmony” which is available online. It is actually more like a “short book” than a paper at 114K words, 316 pp.! See

- HTML version: <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Bastiat/HarmonyDisharmony/index.html>

- PDF version: <davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Bastiat/HarmonyDisharmony/DMH-BastiatHarmonyDisharmony.pdf> [5.9MB]

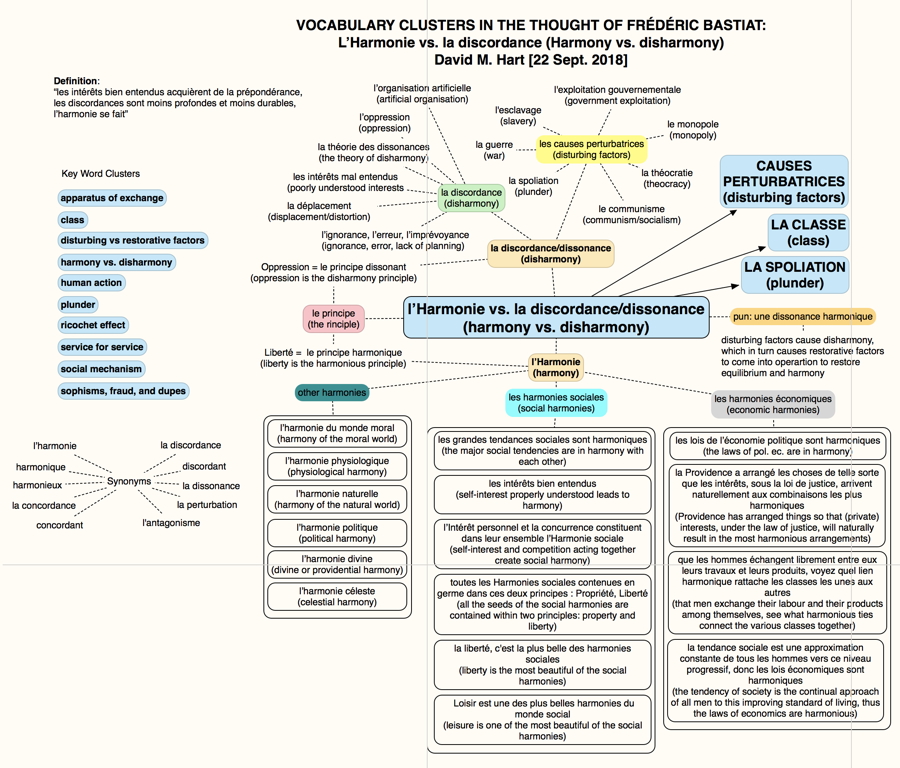

I have also drawn up some “concept maps” to show the very original and specific vocabulary Bastiat developed to discuss his thoughts on these topics. This vocabulary was sometimes hidden or glossed over in the two previous translations of Economic Harmonies which we have (the Stirling translation of the 1860s and the FEE translation of the 1960s). These concept maps can be found in an Appendix to the above paper. I include the one on “Harmony and Disharmony” here.

A Reconstruction of what might have been

I have tried to reorganize Bastiat’s chapters and other writings into something more coherent which follows his plan for a three volume work which dealt with “Social Harmonies,” “Economic Harmonies,” and “The Disharmonies” or “A History of Plunder.”

EH1 = 1st edition of Economic Harmonies (1850)

EH2 = 2nd edition of 1851

WSWNS = What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850)

ES1 = Economic Sophisms (1st series) (1846)

ES2 = Economic Sophisms (2nd series) (1848)

Volume 1: Social Harmonies:

- The two mottoes/sayings [EH2 XII] – one for all (the principle of fellow feeling) and everyone for themselves (the principle of individualism)

- Responsibility – solidarity [EH2 XX and XXI]

- Personal/Self interest or the social drive [EH2 XXII]

- Perfectibility [sketch EH2 XXIV]

- Public opinion (in chap. XXI “Solidarity”)

- liberty and equality [draft chap.]

- The relationship between political economy and morality [sketch EH2 XXV]

- The relationship between political economy and politics

- The relationship between political economy and legislation

- The relationship between political economy and religion. [sketch EH2 XXIII Evil]

Volume 2: Economic Harmonies:

- theoretical matters

- organisation [EH2 I]

- needs efforts, satisfactions [EH2 II and III]

- exchange [EH2 IV]

- value [EH2 V]

- wealth [EH2 VI]

- capital [EH2 VII]

- private property [EH2 VIII]

- communal property (the Commons) [EH2 VIII]

- property in land [EH2 IX]

- competition [EH2 X]

- Producer – Consumer [EH2 XI]

- The theory of Rent [EH2 XIII]

- policy/applied matters

- On money [Damned Money pamphlet]

- On credit [Free Credit debate with P]

- On wages [EH2 XIV]

- On savings [EH2 XV]

- On population [EH2 XVI]

- Private services, public services [EH2 XVII]

- On taxes [WSWNS 3 Taxes]

- On machines [WSWNS 8 Machines]

- Freedom of exchange – (lecture given at Taranne Hall to students in 1847??)

- On intermediaries [WSWNS 6 The Middlemen]

- Raw materials – finished products [ ES1 21 “Raw Materials” (c. 1845)]

- On luxury [WSWNS 11 Thrift and Luxury]

Volume 3: Disharmonies, or The History of Plunder:

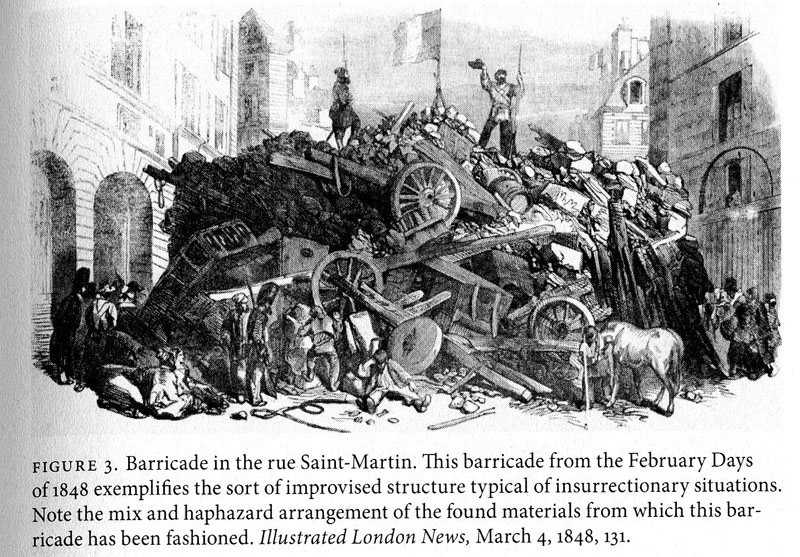

- Plunder [sketch in EH2 XVIII] (conclusion ES1, ES2 1 and 2)

- War [sketch in EH2 XIX]

- Slavery [ES2 1]

- Theocracy [ES2 1]

- Monopoly [ES2 1]

- Governmental exploitation [“functionaryism”]

- False fraternity or Communism [his anti-socialist pamphlets]