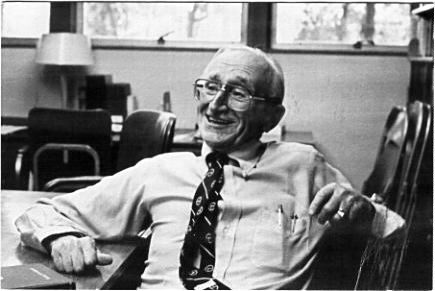

[Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992)]

[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

Since so many contemporary CL/Ls quote Hayek’s 1949 appeal for the rediscovery of a liberal utopia to guide and motivate liberals in their intellectual struggle against fascism, socialism, and other forms of government interventionism I thought it would be useful to put online two lengthy quotations from his work where he discusses this in more detail.

- F.A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism,” The University of Chicago Law Review (Spring 1949), pp. 417-420; reprinted in Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics (University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 178-194. Quotation on pp. 193-94.

- A section in LLL1 entitled “Spurious realism and the required courage to consider utopia”, LLL vol. 1 Rules and Order (1973), Chap. 3 Principles and Expediency, pp. 62-65.

“The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949)

(Section) VII

It may be that as a free society as we have known it carries in itself the forces of its own destruction, that once freedom has been achieved it is taken for granted and ceases to be valued, and that the free growth of ideas which is the essence of a free society will bring about the destruction of the foundations on which it depends. There can be little doubt that in countries like the United States the ideal of freedom today has less real appeal for the young than it has in countries where they have learned what its loss means. On the other hand, there is every sign that in Germany and elsewhere, to the young men who have never known a free society, the task of constructing one can become as exciting and fascinating as any socialist scheme which has appeared during the last hundred years. It is an extraordinary fact, though one which many visitors have experienced, that in speaking to German students about the principles of a liberal society one finds a more responsive and even enthusiastic audience than one can hope to find in any of the Western democracies. [193] In Britain also there is already appearing among the young a new interest in the principles of true liberalism which certainly did not exist a few years ago.

Does this mean that freedom is valued only when it is lost, that the world must everywhere go through a dark phase of socialist totalitarianism before the forces of freedom can gather strength anew? It may be so, but I hope it need not be. Yet, so long as the people who over longer periods determine public opinion continue to be attracted by the ideals of socialism, the trend will continue. If we are to avoid such a development, we must be able to offer a new liberal program which appeals to the imagination. We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage. What we lack is a liberal Utopia, a program which seems neither a mere defense of things as they are nor a diluted kind of socialism, but a truly liberal radicalism which does not spare the susceptibilities of the mighty (including the trade unions), which is not too severely practical, and which does not confine itself to what appears today as politically possible. We need intellectual leaders who are willing to work for an ideal, however small may be the prospects of its early realization. They must be men who are willing to stick to principles and to fight for their full realization, however remote. The practical compromises they must leave to the politicians. Free trade and freedom of opportunity are ideals which still may arouse the imaginations of large numbers, but a mere “reasonable freedom of trade” or a mere “relaxation of controls” is neither intellectually respectable nor likely to inspire any enthusiasm.

The main lesson which the true liberal must learn from the success of the socialists is that it was their courage to be Utopian which gained them the support of the intellectuals and therefore an influence on public opinion which is daily making possible what only recently seemed utterly remote. Those who have concerned themselves exclusively with what seemed practicable in the existing state of opinion have constantly found that even this had rapidly become politically impossible as the result of changes in a public opinion which they have done nothing to guide. Unless we can make the philosophic foundations of a free society once more a living intellectual issue, and its implementation a task which challenges the ingenuity and imagination of our liveliest minds, the prospects of freedom are indeed dark. But if we can regain that belief in the power of ideas which was the mark of liberalism at its best, the battle is not lost. The intellectual revival of liberalism is already underway in many parts of the world. Will it be in time? [194]

“Spurious realism and the required courage to consider utopia” (1973)

With respect to policy, the methodological insight that in the case [62] of complex spontaneous orders we will never be able to determine more than the general principles on which they operate or to predict the particular changes that any event in the environment will bring about, has far-reaching consequences. It means that where we rely on spontaneous ordering forces we shall often not be able to foresee the particular changes by which the necessary adaptation to altered external circumstances will be brought about, and sometimes perhaps not even be able to conceive in what manner the restoration of a disturbed ‘equilibrium’ or ‘balance’ can be accomplished. This ignorance of how the mechanism of the spontaneous order vvill solve such a ‘problem’ which we know must be solved somehow if the overall order is not to disintegrate, often produces a panic-like alarm and the demand for government action for the restoration of the disturbed balance.

Often it is even the acquisition of a partial insight into the character of the spontaneous overall order that becomes the cause of the demands for deliberate control. So long as the balance of trade, or the correspondence of supply and demand of any particular commodity, adjusted itself spontaneously after any disturbance, men rarely asked themselves how this happened. But, once they became aware of the necessity of such constant readjustments, they felt that somebody must be made responsible for deliberately bringing them about. The economist, from the very nature of his schematic picture of the spontaneous order, could counter such apprehension only by the confident assertion that the required new balance would establish itself somehow if we did not interfere with the spontaneous forces; but, as he is usually unable to predict precisely how this would happen, his assertions were not very convincing.

Yet when it is possible to foresee how the spontaneous forces are likely to restore the disturbed balance, the situation becomes even worse. The necessity of adaptation to unforeseen events will always mean that someone is going to be hurt, that someone’s expectations will be disappointed or his efforts frustrated. This leads to the demand that the required adjustment be brought about by deliberate guidance, which in practice must mean that authority is to decide who is to be hurt. The effect of this is often that necessary adjustments will be prevented whenever they can be foreseen.

What helpful insight science can provide for the guidance of policy consists in an understanding of the general nature of the spontaneous order, and not in any knowledge of the particulars of [63] a concrete situation, which it does not and cannot possess. The true appreciation of what science has to contribute to the solution of our political tasks, which in the nineteenth century was fairly general, has been obscured by the new tendency derived from a now fashionable misconception of the nature of scientific method: the belief that science consists of a collection of particular observed facts, which is erroneous so far as science in general is concerned, but doubly misleading where we have to deal with the parts of a complex spontaneous order. Since all the events in any part of such an order are interdependent, and an abstract order of this sort has no recurrent concrete parts which can be identified by individual attributes, it is necessarily vain to try to discover by observation regularities in any of its parts. The only theory which in this field can lay claim to scientific status is the theory of the order as a whole; and such a theory (although it has, of course, to be tested on the facts) can never be achieved inductively by observation but only through constructing mental models made up from the observable elements.

The myopic view of science that concentrates on the study of particular facts because they alone are empirically observable, and advocates even pride themselves on not being guided by such a conception of the overall order as can be obtained only by what they call ‘abstract speculation’, by no means increases our power of shaping a desirable order, but in fact deprives us of all effective guidance for successful action. The spurious ‘realism’ which deceives itself in believing that it can dispense with any guiding conception of the nature of the overall order, and confines itself to an examination of particular ‘techniques’ for achieving particular results, is in reality highly unrealistic. Especially when this attitude leads, as it frequently does, to a judgment of the advisability of particular measures by consideration of the ‘practicability’ in the given political climate of opinion, it often tends merely to drive us further into an impasse. Such must be the ultimate results of successive measures which all tend to destroy the overall order that their advocates at the same time tacitly assume to exist.

It is not to be denied that to some extent the guiding model of the overall order will always be an utopia, something to which the existing situation will be only a distant approximation and which many people will regard as wholly impractical. Yet it is only by constantly holding up the guiding conception of an internally consistent model which could be realized by the consistent application [64] of the same principles, that anything like an effective framework for a functioning spontaneous order will be achieved. Adam Smith thought that ‘to expect, indeed, that freedom of trade should ever be entirely restored in Great Britain is as absurd as to expect an Oceana or Utopia should ever be established in it.’ [FN14] Yet seventy year later, largely as a result of his work, it was achieved.

Utopia, like ideology, is a bad word today; and it is true that most utopias aim at radically redesigning society and suffer from internal contradictions which make their realization impossible. But an ideal picture of a society which may not be wholly achievable, or a guiding conception of the overall order to be aimed at, is nevertheless not only the indispensable precondition of any rational policy, but also the chief contribution that science can make to the solution of the problems of practical policy.