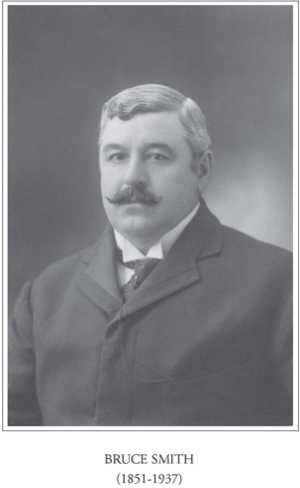

The important although little known Australian classical liberal Bruce Smith (1851–1937) was one of the very few voices in Australia arguing for a radical and consistent liberalism in opposition to the statist (i.e. interventionist) version of liberalism which was home-grown in the colonies and the equally interventionist “New Liberalism” which was being imported from Britain. Greg Lindsay and Gregory Melluish of the Centre for Independent Studies in Sydney attempted to revive interest in his work with the republication in 2005 of his main book Liberty and Liberalism: A Protest against the growing Tendency toward undue Interference by the State, with Individual Liberty, Private Enterprise and the Rights of Property (1887), with some assistance from myself. I got the text coded, they published it in book form, and I put it on the Online Library of Liberty which I directed. See it here.

I have now added the text to my own website, along with some biographical material about Smith, and a copy of another of his books Truisms of Statecraft: An Attempt to Define, in General Terms, the Origin, Growth, Purpose, and Possibilities, of Popular Government (London: Longmans, 1921). See the main page for Australian Classical Liberals and Libertarians, the Bruce Smith bio page, and the HTML version of Liberty and Liberalism here.

David Kemp devotes some space to discussing Smith’s ideas in A Free Country: Australians’ Search for Utopia 1861–1901 (2019) which suggests he is sympathetic to Smith’s kind of classical liberalism, which derived from the English radical liberal Herbert Spencer and the people around the Liberty and Property Defense League, which he contrasts with the other source of influence on Australian liberal thought, that of the much more moderate and even interventionist ideas of John Stuart Mill. The protectionists in Australia seized upon Mill’s glaring exception to the principle of free trade, namely the “infant industries argument” as a justification for the protectionist party in Victoria which ultimately was able to make this policy one of the foundation stones of Australia’s deeply flawed federation of 1901. The other dead-weight stones which were hung around the neck of Australian liberty were the racist White Australia policy, the deeply interventionist compulsory labour arbitration system, and the state socialism of government owned and run railways and other “infrastructure”). Smith opposed all of these awful policies but had little influence over the ultimate outcome.

As Greg Melluish notes in his Introduction:

Bruce Smith’s *Liberty and Liberalism* is significant for two major reasons. The first is that it was the one major critique of the new liberalism produced in the Australian colonies. The second is that it is the most important theoretical expression of classical liberalism written in Australia. It was an account of liberalism that owed a lot to the principles of Darwinian evolution. In part, its significance lies in the fact that it owes its intellectual substance to the Melbourne school of free trade liberalism which has largely been ignored by historians such as Stuart Macintyre who have focused primarily on statist liberals such as Syme, Pearson and Deakin.

And that his influence ultimately lies not in his “political success” or lack thereof but:

… the importance of Smith’s political career did not lie in his political achievements. They were not substantial. Rather Smith’s continuing presence in public life was important because through him the tradition of classical liberalism also continued to have a public presence. There has been a tendency to paint both Smith and his work on liberalism as some sort of anachronistic dinosaur, a vestige from an earlier age. This is both incorrect and highly ideological. It rests on the dangerous notion that liberalism was being ‘progressive’ by becoming more statist.

It seems that Australian libertarians have to still face the same charges some 140 years later.

In re-reading the book I came across a couple of my favourite passages which I include below as an appetiser to reading the entire book. The first is his view of what it is the limited state should actually do; and the second is his view of the role of the state in education, mass, compulsory, state education being one of the cornerstones of the edifice of the Australian state for both “left” and “right”.

On the proper function of a “legislator” (CIS ed. pp. 299-300):

The broad principles, then, which I should venture to lay down as guides for any one assuming the responsible position of a legislator are three in number.

1. The state should not *impose taxes*, or *use the public revenue* for any purpose other than that of *securing equal freedom to all citizens*.(29)

2. The state should not interfere with the *legally acquired property* of any section of its citizens for any other purpose than that of *securing equal freedom to all citizens;* and in the event of any such justifiable interference amounting to appropriation; then, only conditional upon the lawful owner being *fully compensated*.

3. The state should not in any way restrict *the personal liberty* of citizens for any other purpose than that of *securing equal freedom to all citizens*.I repeat that I do not offer these as *conclusive tests* of the wisdom of any proposed legislation. I claim for them this use, however, that they should, in every case, be applied to any such proposal; and if, on such application, the new rights sought to be conferred, and the restrictions on liberty which they must necessarily involve, do not conflict with either of the three principles, there can be little objection to its legislative sanction. If, however, any such proposal *is* found to come into conflict with either of those principles; then, I contend, a great responsibility is cast upon him or them who demand the interference of the legislature; and he or they should be forced to prove, conclusively, that the necessity for the proposal is *so urgent* that it overrides the consideration of its transgressing one of the fundamental principles upon which our social system has been built up. He should be compelled, too, to show a strong probability that the proposed means *will effect the desired end*, without producing an *equally or more injurious* result to society, in *some other direction*, or at *some other time*. The effect of the regular application of these principles to proposed measures would be, in the first place, to determine on which side the burden of proof lay; and then it would rest with those who have cast upon them the responsibility of giving the legislative sanction, to determine (1) whether the *necessity* has been proved; (2) whether, under all the circumstances of the case, that necessity is *sufficiently urgent* to justify the subversion of a principle which is immemorial, and which has for centuries served as one of the pillars of our social fabric; (3) whether it has been shown that the proposed measure will effect the purpose aimed at, without, at the same time, producing injurious results to society in *some other*, perhaps unsuspected, *direction*, or at *some other time*.(30)

Smith’s Notes

(29) I am well aware that the first of these three principles could, strictly speaking, be included within the second, for to impose taxes is really to interfere with property; and to use the public revenue, in which each and every citizen has an interest, practically produces a similar result; but inasmuch as the lapping of the two is not palpable, I have chosen to separate them.

(30) “It is not sufficient (says Professor Stanley Jevons) to show by direct experiment or other incontestable evidence that an addition of happiness is made. We must also assure ourselves that there is no equivalent or greater subtraction of happiness—a substraction which may take effect either as regards other people or subsequent times.”

And on education (CIS ed. pp. 307 ff.):

*State Education*.—I have no hesitation in characterising the maintenance of state education as a distinct transgression of the first principle of the three which I have deduced from an analysis of man’s wants as an individual member of society, viz., that the state should not *impose taxes, or use the public revenue* for any other purpose than that of *securing equal freedom to all citizens*. It is undoubtedly true that every citizen should have the *liberty* to be educated if he so wish; but state education, as now established in most English-speaking communities, involves a recognition of a right to be supplied with the *means* by which to secure such education. No one, I think, has ever seriously disputed the proposition with which I have opened this section of the present chapter. With the exception of Mr. Herbert Spencer’s treatment of the subject in his “Social Statics,” I do not think any other writer has recorded his objections to the system on that ground. …

… But now, having admitted so much, I have yet to ask—should the state *supply* this education? Are there not a hundred things more necessary for all classes? However desirable reading, writing, and arithmetic may be, mankind succeeded without them. Is not food more important—is it not absolutely indispensable? So also clothing, shelter, warmth in winter, medicine in sickness. Is it not more important that the food we eat should be wholesome, than that our education should be good? Yet the state takes upon itself none of these wants. It does not undertake the supply of meat, bread, butter, or milk. It does not concern itself about the thickness or sufficiency of our clothing; about the temperature of our dwellings. Surely the proper feeding of the *body* is of as much importance as the feeding of the *mind*. Then why should education be undertaken by the state? While many hundreds of children, in Great Britain, are being taught to read and write, they are suffering from a want of clothing, and in some cases from an empty stomach. Why does the state not come to the rescue in those more important wants? There must surely be some other reason for state interference in this matter. Now, the advocates of state education have John Stuart Mill on their side. Let us then see what arguments he advances. In the first place, he justifies the state taking education in hand on the ground that it is one of those commodities which the consumer cannot judge for himself. He, therefore, claims it as an exception to the rule of allowing the individual to be the judge of his own wants. Practically, this means that every man, being a judge of butter, or sugar, or bread, or meat, or cloth, or linen, he should be left to look after his own interest; but in matters in which he is *not* a “competent judge” it is “admissible in principle that the government should provide it” for him. Considering the authority from which this doctrine comes, it is indeed extraordinary. Let us see where it would lead. Mill himself admits that even in “material objects produced for our use,” it is “not true universally” that the consumer is the best judge. If this is so, which we may assume on the admission, should the state provide for the stupid people? Should the state undertake the function of advising citizens what is, and what is not a good article? This is really what Mill’s doctrine would lead to. To go further; if the state is only to interfere when the inability of the consumer to judge the article is tolerably universal, why should not the state take in hand the work now performed by lawyers, physicians, and chemists? How many of the public are “competent judges” of law or physic? How many of them are “competent judges” as to whether they really want such advice? Surely the state should come in here also! I cannot follow up the illustrations of its unsoundness as an argument; but it applies to such subjects of “consumption” as art, literature, the drama, and even the sciences. It is true that the masses are not “competent” judges of the higher branches of culture; but is it not unreasonable to assume that their ignorance is so profound that they cannot appreciate the advantages of reading the newspaper, writing a letter, and being able to correctly add up an account, or expeditiously check the money-change which they receive in their every-day transactions? Yet these are obvious results of the ordinary state-school curriculum, and if any part of the masses are so dense that they cannot really discern these advantages, I venture to think that when the schooling has been forced upon them it will not be to much purpose. But if this reason—the inability of the consumer to judge any commodity for himself—is a sufficient one for justifying the assumption by the state of the supply of that commodity, where is the result to terminate?