About Richard Overton

Richard Overton (c. 1599–1664) is one of the intellectual and political leaders of the Levellers during the English Revolution. Little is known about his early life although he probably graduated from Queens College, Cambridge and worked as an actor before becoming involved in political pamphleteering at which he excelled. He wrote dozens of pamphlets in the early 1640s in which he attacked Catholicism and the Anglican establishment. He may have been imprisoned for debt in 1642 which kept him silent for a while but he returned to the fray with a popular tract “Mans Mortalitie” (1643) in which he argued that man’s soul died with him and was not resurrected until Judgement Day. Overton became close friends with William Walwyn and John Lilburne who co-authored many tracts with him.

Gradually his concerns moved from the religious to more political and philosophical matters as he developed more general theories about the equality of all men under the law, the need for Parliament to represent the interests of all citizens, the need to replace the Monarch with a republican form of government, and opposition to the system of class and political privilege which governed the British state. In addition to many individual pamphlets he also wrote editorials for the Leveller weekly journal The Moderate.

As a leader of the Leveller movement he was often singled out and imprisoned in Newgate and The Tower between 1846-47 from which he continued to write and protest, most notable of these is his “An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyrany” (Oct. 1646) written or “fired” (as he put it) from the Newgate prison; and then again in 1649. After Cromwell crushed the Leveller movement in 1649 Overton sought exile in Holland and little is known about his activities after that date.

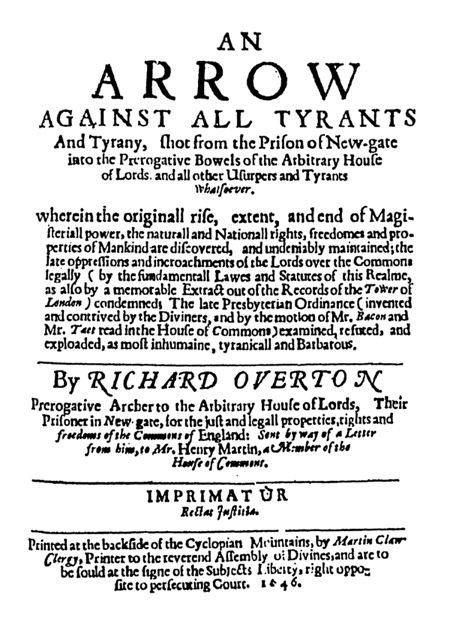

“An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyrany” is his best known pamphlet and it shows both Overton’s satirical and hard-hitting style of writing and the radicalism of his ideas. It begins with a typical long title which neatly summarizes his arguments, contains a mocking and irreverent place of publication in order to deceive the censors, and supporting documents to bolster his case for appeal. It then has an eloquent defence of the idea of the natural rights to liberty and property which all men have, regardless of their station in life, and is followed by two specific grievances against the growing encroachments on liberty by the House of Lords and the Presbyterian clergy, before closing with some veiled threats against what might happen to “England’s Bloody Parliament” if these grievances are not remedied.

About “An Arrow against all Tyrants and Tyrany”

See the whole pamphlet.

As he says, Richard Overton fired this arrow “against all tyrants” while he was in Newgate prison in October 1646. He was imprisoned there for lengthy periods between August 1646 and September 1647; and then again in the Tower of London with the other Levellers John Lilburne, William Walwyn, and Thomas Prince during the crackdown on the movement by Cromwell between March and November 1649. In spite of this he was able to write about 40 pamphlets in which he expressed some of the most radical and consistent political views of the Leveller movement. His ideas were strongly democratic (urging the right to vote of ordinary working men) and republican (thus breaking with the more moderate Parliamentarians who wanted to create a constitutional monarchy) and were based upon the following ideas.

He believed that under natural law all men were equal, that there existed a social contract which was the only legitimate foundation of society, that the traditional liberties of Englishmen had been crushed by the invading Normans who placed them under a “yoke” of tyranny, but that successive agreements made with the monarchs who followed (such as Magna Carta) had created a system of “fundamental laws” guaranteeing individual liberty which all monarchs and parliaments were obliged to uphold and defend, that ultimately the people were the sovereign power (not the King) and all representatives of the people were accountable to them.

In this justly famous pamphlet Overton begins by providing a clear and passionate defence of the idea of “self-ownership” (or “self propriety” as he called it) upon which rested all other claims to liberty by an individual. The opening paragraph of the pamphlet states:

TO every Individuall in nature, is given an individuall property by nature, not to be invaded or usurped by any: for every one as he is himselfe, so he hath a selfe propriety, else could he not be himselfe, and on this no second may presume to deprive any of, without manifest violation and affront to the very principles of nature, and of the Rules of equity and justice between man and man; mine and thine cannot be, except this be: No man hath power over my rights and liberties, and I over no mans; I may be but an Individuall, enjoy *my selfe* and my selfe propriety, and may write my selfe no more then my selfe, or presume any further; if I doe, I am an encroacher & an invader upon an other mans Right, to which I have no *Right.* For by naturall birth, all men are equally and alike borne to like propriety, liberty and freedome, and as we are delivered of God by the hand of nature into this world, every one with a naturall, innate freedome and propriety (as it were writ in the table of every mans heart, never to be obliterated) even so are we to live, every one equally and alike to enjoy his Birth-right and priviledge; even all whereof God by nature hath made him free.

And by individual, he meant all male individuals, not just the wealthy or privileged. According to Overton “by nature we are the sons of Adam” (the daughters of Adam would have to wait a few more centuries – although Mary Chidley and Margaret Fell might beg to disagree with him) from whom we have derived our natural rights to property and liberty. These natural rights belonged to everybody, and as he admonished a member of Parliament:

Be you therefore impartiall, and just, active and resolute care neither for favours nor smiles, and be no respector of persons, let not the *greatest Peers* in the Land, be more respected with you, then so many *old Bellowes-menders, Broom men, Coblers, Tinkers or Chimney-sweepers,* who are all equally *Free borne;* with the hudgest men, and *loftiest Anachims* in the Land.

However, these natural rights of “Free borne Englishmen” were violated by power hungry and ambitious “opportunity Politicians” and intolerant and oppressive Presbyterian Clergymen who behaved like so many “ravening wolves, even as roaring Lyons wanting their pray, going up and down, seeking whom they may devour.”

The true radicalism of Overton’s political views can be found in his comparison of the government to a school master privately employed by a father to teach his children and who can be removed at will if he does not not perform his job satisfactorily:

So that such so deputed, are to the *Generall* no otherwise, then as a Schoole-master to a particular, to this or that mans familie, for as such an ones Mastership, ordering and regulating power, is but by deputation, and that *ad bene placitum,* and may be removed at the parents or Head masters pleasure, upon neglect or abuse thereof, and be confer’d upon another (no parents ever giving such an absolute unlimited power to such over their children, as to doe to them as they list, and not to be retracted, controuled, or restrained in their exorbitances) Even so and no otherwise is it, with you our Deputies in respect of the Generall, it is in vaine for you to thinke you have power over us, to save us or destroy us at your pleasure, to doe with us as you list, be it for our weale, or be it for our wo …

After 1649 little is known of Overton’s movements. He spent some time in exile in the Netherlands only to resurface briefly in the mid-1650s when he became involved in Sexby’s plots to overthrow and perhaps even assassinate Cromwell (see his Killing no Murder (Sept. 1657)). He was arrested again in 1659 and may have spent time in prison. He seems to have completely disappeared from view by the end of 1662 and the place and date of his death are unknown.

A final thing to note is Overton’s hallmark insertion of a contemptuous and also fake statement about the name and location of the pamphlet’s publisher:

Printed at the backside of the Cyclopian Mountains, by Martin Claw-Clergy, Printer to the reverend Assembly of Divines, and are to be sould at the signe of the Subjects Liberty, right opposite to persecuting Court. 1646.

Pingback: Google

Pingback: tinder: tinder dating: the ultimate beginner's guide

Pingback: what happens when you take viagra

Pingback: free black people dating