A Selection of his Articles from the DEP (1852-53)

While he was writing his book Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare over the summer of 1849 Molinari was also working on 30 articles which would appear in the most important publication the Guillaumin publishing firm had undertaken up to that time, namely the Dictionnaire de l’Économie Politique (Dictionary of Political Economy). It was a key part of the Guillaumin firm’s strategy to counter the growing support for socialist ideas revealed by the success of socialist groups like the Montagnards during the 1848 Revolution, and the continuing support for interventionist and protectionist policies by Napoleon’s government during the Second Republic.

To counter these ideas among the general public Guillaumin published works like Bastiat’s Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848) and turned into cheap pamphlets several of his articles written for journals like Le Journal des débats (“The State”) and the Journal des Économistes (“Plunder and Law”) or which they commissioned as stand alone pamphlets like The Law (July 1850). Guillaumin also commissioned younger economists like Molinari to turn their hand to writing for a popular audience like his book Les Soirées.

To counter the false ideas held by the political and intellectual elites which governed France the Guillaumin undertook the massive DEP project in which Molinari played an important role, being a kid of de facto co-editor of the project under Charles Coquelin (who died before the project was completed). The purpose was to assemble a compendium of the state of knowledge of liberal political economy with hundreds of articles written by leading economists on key topics, biographies of important historical figures, annotated bibliographies of the most important books in the field, and tables of economic and political statistics.

The DEP project was most likely conceived in late 1848 or early 1849, was announced in the Guillaumin catalog of May 1849 as being “in preparation,” was made available in subscription form in August 1849, and the first volume of which was printed in book form in early to mid-1852. The end result was a two volume, nearly 2,000 page, double-columned, nearly 2 million word encyclopedia of political economy which appeared in 1852-53.

Molinari was a major contributor to the Project, writing 25 principle articles and five biographical articles. In the acknowledgements he was mentioned as one of the five key collaborators on the project. Other economists who made significant contributors to the project were the main editor Coquelin, who died suddenly in August 1852 before he could start work on volume 2 and who wrote 70 principle articles, Horace Say (29), Joseph Garnier (28), Ambroise Clément (22), and Courcelle-Seneuil (21). Maurice Block wrote most of the biographical entries and Bastiat contributed three which appeared posthumously. Molinari’s articles were the following (those in bold have been translated into English):

Biographical Articles (5):

- “Necker,” T. 2, pp. 272-74.

- “Peel (Robert),” T. 2, pp. 351-54.

- “Saint-Pierre (abbé de),” T. 2, pp. 565-66.

- “Sully (duc de),” T. 2, pp. 684-85.

Principle Articles (24):

- “Beaux-arts” (Fine Arts) , T. 1, pp. 149-57.

- “Céréales” (Grain), T. 1, pp. 301-26.

- “Civilisation” (Civilization) , T. 1, pp. 370-77.

- “Colonies,” T. 1, pp. 393-403.

- “Colonies agricoles” (Agricultural Colonies), T. 1, pp. 403-5.

- “Colonies militaires” (Military Colonies), T. 1, p. 405.

- “Émigration” (Emigration), T. 1, pp. 675-83.

- “Esclavage” (Slavery), T. 1, pp. 712-31.

- “Liberté des échanges (Associations pour la)” (Free Trade Associations), T. 2, p. 45-49.

- “Liberté du commerce, liberté des échanges” (Freedom of Commerce. Free Trade) , T. 2, pp. 49-63.

- “Mode” (Fashion) , T. 2, pp. 193-96.

- “Monuments publics” (Public Monuments), T. 2, pp. 237-8.

- “Nations” (Nations) , T. 2, pp. 259-62.

- “Noblesse” (The Nobility) , T2, pp. 275-81

- “Paix, Guerre” (Peace. War), T. 2, pp. 307-14.

- “Paix (Société et Congrès de la Paix)” (The Society and Congress for Peace), T. 2, pp. 314-15.

- “Propriété littéraire et artistique” (Literary and Artistic Property), T. 2, pp. 473-78

- “Servage” (Serfdom), T. 2, pp. 610-13

- “Tarifs de douane” (Customs Tariffs), T. 2, pp. 712-16.

- “Théâtres” (Theaters), T. 2, pp. 731-33.

- “Travail” (Labor), vol. 2, pp. 761-64.

- “Union douanière” (Customs Union), vol. 2, p. 788-89.

- “Usure” (Usury), vol. 2, pp. 790-95.

- “Villes” (Towns) , T. 2, pp. 833-38.

- “Voyages” (Travel), T. 2, pp. 858-60.

The seven articles in bold were translated into English for Lalor’s Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy (1881) (see below for details), and are available online here. All thirty in French are available here with an introduction in English.

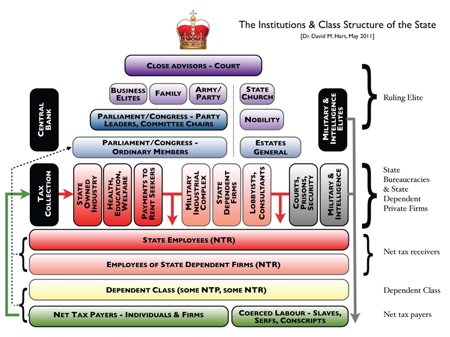

The topics he focused on were two that were dear to his heart and on which he had already written, namely free trade and slavery. Concerning free trade, he wrote the articles on Grain, Free Trade Associations, Freedom of Commerce. Free Trade, Customs Tariffs, and Customs Union. Concerning slavery, he wrote the articles on Slavery and Serfdom. On more specialised topics on which he would also write in Les Soirées , we should note those on Fine Arts, Literary and Artistic Property, Theaters, Labor, and Usury. Another group of topics that deserve special mention are those to which one normally would not expect to see economic analysis applied, such as Emigration, Fashion, Fine Arts, Public Monuments, and Travel. The latter suggest that Molinari had an innovative way of thinking about all manner of social and cultural problems and using economic analysis to deepen our understanding of them in new and interesting ways. Among these one would include the formation of cities and towns and his growing interest in class analysis

Thirty years after the appearance of the DEP the American political scientist and economist John Joseph Lalor (1840-1899) attempted to do something similar for the English-speaking world with his Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States (first ed. 1881-84, second edition 1899). In addition to his own formidable list of American authors he included translations of one hundred articles from the DEP including many by Bastiat, Henri Baudrillart, Michel Chevalier, Cherbuliez, Ambroise Clément, Charles Coquelin, Léon Faucher, Joseph Garnier, J.E. Horn, Louis Leclerc, H. Passy, members of the Say family, Courcelle-Seneuil, and of course Molinari. This constituted a veritable “who’s who” of the economists in the Guillaumin network. Just as America was moving further into the protectionist camp, Lalor and his colleagues were translating some of the hardest of hard-core French free trade advocates, such as Molinari’s “Freedom of Commerce. Free Trade,” and offering it to American readers. The impact of this infusion of French political economy into America seems to have been minimal if anything, but it was a remarkably undertaking.

See the list of all the articles from the DEP which were translated and published in Lalor’s Cyclopedia.