[Honoré Daumier’s “Le Défenseur (Council for the Defense),” c. 1862-1865.]

Note: This is part of a collection of posts on “The Current State of Liberty and the Threats it faces”.

In this post I want to discuss the following issues:

- the multi-dimensional nature of Liberty requires a multi-dimensional approach to arguing for it

- the main kinds of arguments we can use: moral, economic, political, historical

- identifying those who might be sympathetic to arguments for Liberty

- identifying those who are likely to be resistant to arguments for Liberty

- the impediments we face in making the argument for Liberty

The Multi-Dimensional Nature of Liberty requires a Multi-Dimensional Approach to arguing for it

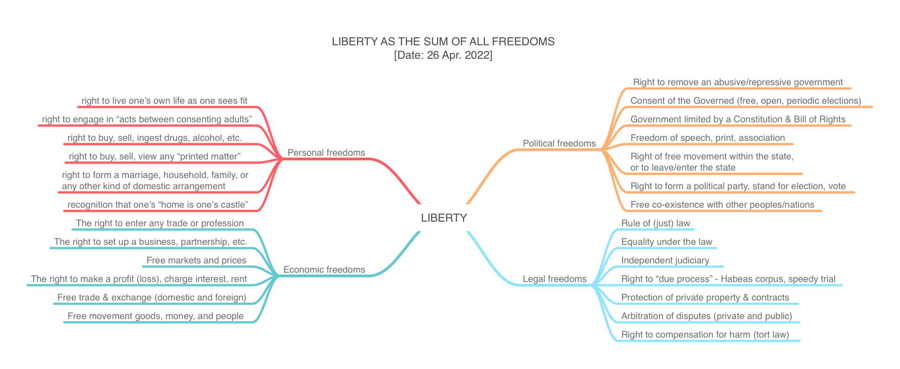

I will quote again here the important observation of the French political economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) who most eloquently made the point that “Liberty” is made up of a collection of other “freedoms”:

[French original] – Et qu’est-ce que la Liberté, ce mot qui a la puissance de faire battre tous les cœurs et d’agiter le monde, si ce n’est l’ensemble de toutes les libertés, liberté de conscience, d’enseignement, d’association, de presse, de locomotion, de travail, d’échange; d’autres termes, le franc exercice, pour tous, de toutes les facultés inoffensives; en d’autres termes encore, la destruction de tous les despotismes, même le despotisme légal, et la réduction de la Loi à sa seule attribution rationnelle, qui est de régulariser le Droit individuel de légitime défense ou de réprimer l’injustice.

[my revised translation 13 Aug. 2021] – And what is “Liberty,” this word that has the power of making all hearts beat faster and of moving the entire world, if it is not the sum of all freedoms? — freedom of conscience, teaching, and association, freedom of the press, freedom to travel, work, and trade, in other words, the free exercise by all people of all their non-aggressive abilities. And, in still other terms, isn’t freedom the destruction of all despotic regimes, even legal despotism, and the limiting of the law to its sole rational function which is to regulate the individual’s right of legitimate self defense and to prevent injustice?

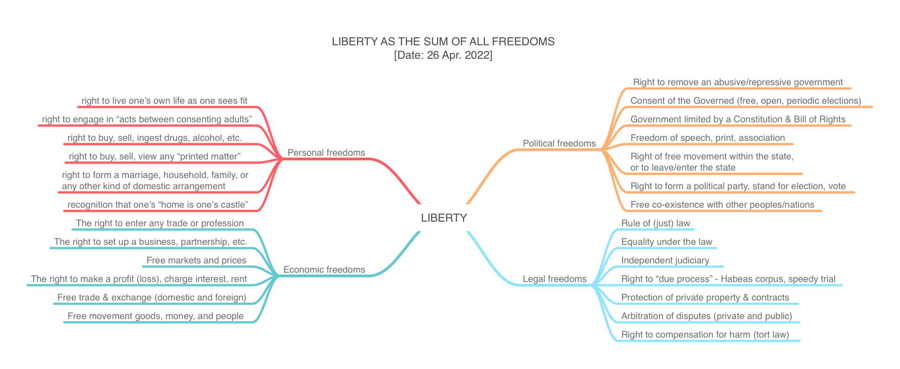

In my formulation of this insight, I group these “freedoms” into 4 major categories: personal freedoms, economic freedoms, political freedoms, and legal freedoms.

[See my post on “Liberty as the Sum of All Freedoms” (26 April, 2022) here and this accompanying schematic.]

.

.

Different political ideologies may (or may not) focus on a few freedoms from this broader list (or “palette” if you like) but only the CL appreciates the importance of “the group of four” as comprising a consistent whole based upon the foundational principles of avoiding the use of coercion and respecting every individual’s rights to life, liberty, and property.

Some Thoughts on Strategy

- if someone expresses interest in, say, economic liberty but not so much (if at all) for the other forms of liberty, then we need to show them the necessary and logical connections between the different kinds of liberty; this of course assumes that people think that logical consistency matters; this view was shared by Milton Friedman who believed economic and political liberty were intimately connected and that you couldn’t have one without the other (the existence of Singapore might be a good reason for rethinking Friedman’s position)

- if someone expresses interest in one kind of economic liberty but not other kinds, we need again to show them how one liberty is connected to the others, and how they rest on the same or very similar principles

The main Kinds of Arguments we can use: moral, economic, political, historical

It is my view that there are four grounds on which the case for CL rests: moral, economic, political, and historical grounds. These grounds can be used as the basis for different kinds of arguments we can use to advocate CL. Very briefly they can be summarised as follows:

- the moral grounds: CLs believe that there is a strong moral argument for having respect for the individual as a unique and important person with rights to themselves (self-ownership), and also rights to property and liberty; and that the use of coercion violates these fundamental rights

- the economic grounds: letting people be free to engage in all kinds of non-coercive economic activity, to trade with each for mutual benefit, is the best way we know how to increase prosperity for both these individuals and for the broader society in which they live and work

- the political grounds: “liberal democracy” operating within a constitutional framework and “the rule of (just) law” is the best means we know to limit the power of the predatory state in order to allow individuals to live their lives and go about their business as they fit, to guarantee the ownership and enjoyment of property, and protect the functioning of “civil society” [note here Hayek’s important distinction between “law” and “legislation” – the “rule of law” is completely different from the “rule of legislation”.]

- the historical grounds: in spite of the fact that I think that the old “Whig interpretation of history” and the more recent arguments of Francis Fukuyama about “the end of history” are incorrect, it is true that after centuries of often bitter and bloody conflict some countries were able to build fairly liberal societies which protected individual rights to life, liberty and property (what I have called “the Great Emancipation”), which was the precondition for “the Great Enrichment” the benefits of which we still enjoy today. The fact that this actually occurred in “liberal societies” and not authoritarian or communist ones is a very important factor in the case for CL. The other side of the coin, which CLs should not tire of telling people about, are the catastrophic results of central planning, whether attempted on a universal scale in the Soviet Union and Communist China, but also on a more modest scale by all governments around the world (in Australia the National Broadband Network is a good example, as was the attempt during the Covid lockdowns to bureaucratically decide which was an “essential industry” and which was not).

[See my posts on “Classical Liberalism as a Revolutionary Ideology of Emancipation” (13 Oct. 2021) here, and “A Balance Sheet of the Success and Failures of Classical Liberalism” (21 Apr. 2022) here.]

Since different people respond differently to different kinds of arguments, it is important to choose the right kind of argument to suit a particular person’s interests and inclinations.

Some Thoughts on Strategy

- Some people find “economic” arguments repulsive / heartless and respond better to ones based on moral or ethical arguments

- Other people reject ethical arguments (say based on natural law and natural rights principles) and thus are more interested in “hard headed” economic or utilitarian arguments which stress the waste and economic inefficiency of government intervention, or the impediments intervention erects in front of economic expansion and development

- if people insist that in a crisis “the government has to do something” we can point out how similar efforts have failed in the past (historical), how such efforts are usually doomed to failure (economic), and how such efforts usually result in an increase in the size and power of government which is very hard (if not impossible) to remove afterwards (political, historical)

- people often argue that there are certain “public goods” which only the government can provide; this argument can be countered with the many historical examples we have of non-government, voluntary, and for profit market solutions to these problems (historical)

Identifying those who might be sympathetic to arguments for Liberty

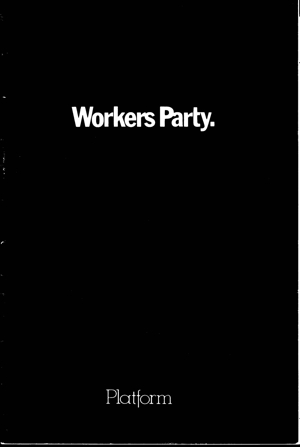

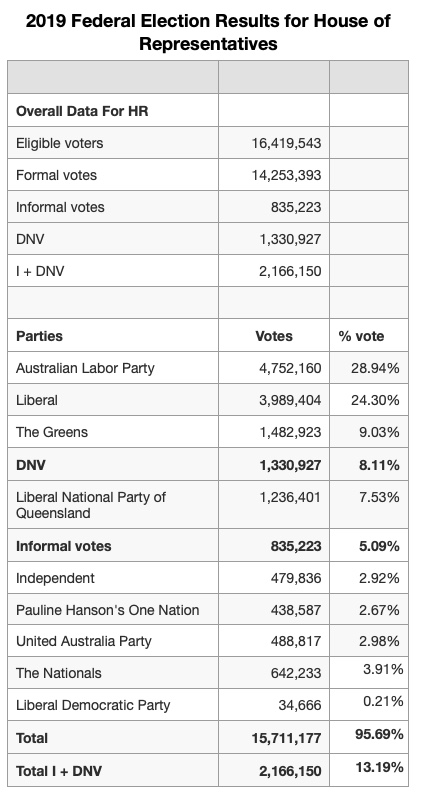

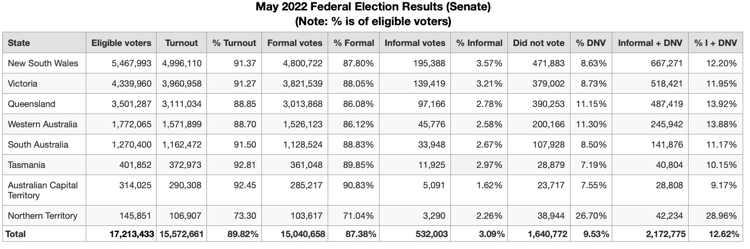

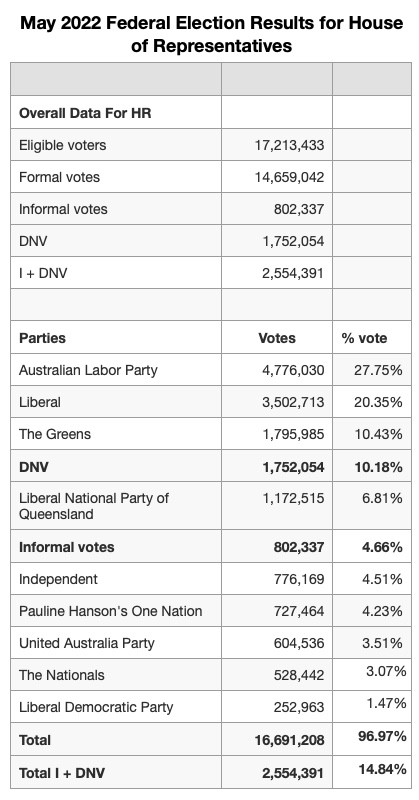

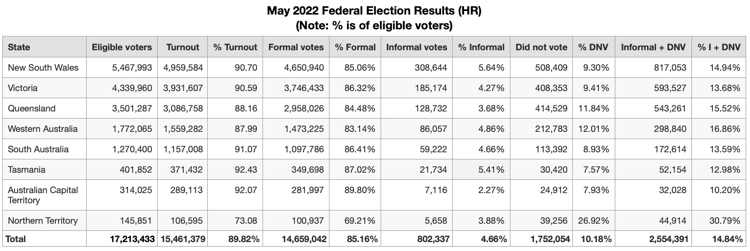

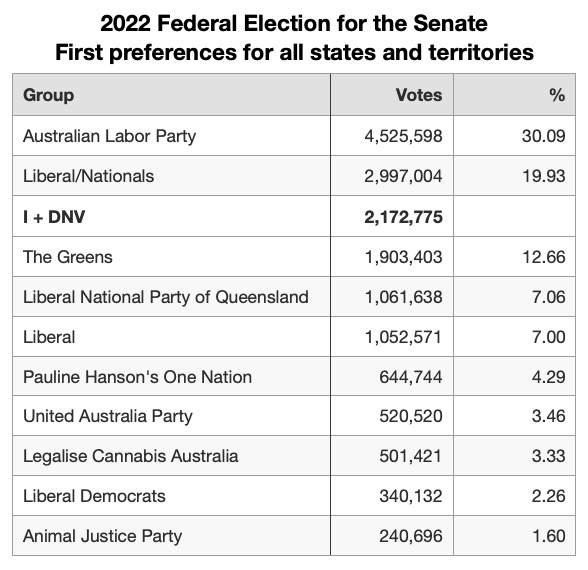

In spite of the pro-state and anti-market stance taken for decades in the school curriculums and adopted for the most part in the universities, there are still a few individuals who are sympathetic to the ideals of the free market and the limited state. Many have become disconnected from the political mainstream (and do not vote at all or vote “informal”, i.e. in non-state approved methods) or are resigned to choosing the “least-bad” alternative in elections, and therefore “hold their nose” when they are in the voting booth.

Here is my list of those who might be sympathetic to arguments for Liberty and on whom we might focus our limited time and resources:

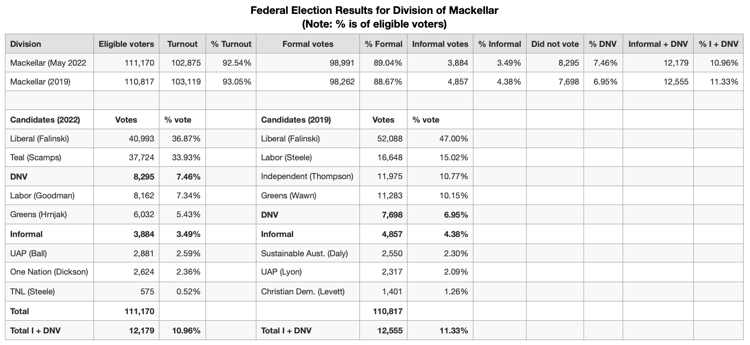

- the disconnected voter or the “swinging” voter who is “shopping around”; it is the job of a CL political party to find these people and persuade them to vote for candidates who truly believe in individual liberty and free markets. [See my post on this group in “Some Thoughts on the May 2022 Federal Election in Australia” (26 May 2022) here.]

- people who are still forming their political and economic opinions, such as students, or those who have become disillusioned with the status quo and are looking for an alternative; this is the job for groups like Mannkal, CIS, IPA, or FEE in the US

- educated people who might be swayed at the margin to vote for lower taxes and more limited government; they are not “true believers” but might be persuaded to become one in time (CIS, IPA, the Cato Institute in the US)

- sympathetic academics and intellectuals such as journalists, writers, artistic types (if there are any!) (IPA, CIS, Liberty Fund in the US)

- those groups who resent paying more in taxes than they receive in benefits, who are appalled at the waste and inefficiency of government, or who disapprove of some of the recipients of government subsidies and transfer payments; some of these people have been attracted to anti-establishment parties like One Nation or United Australia; whether they can be persuaded to join a more consistent CL group remains to be seen as they have “populist” economic notions which run against free market principles

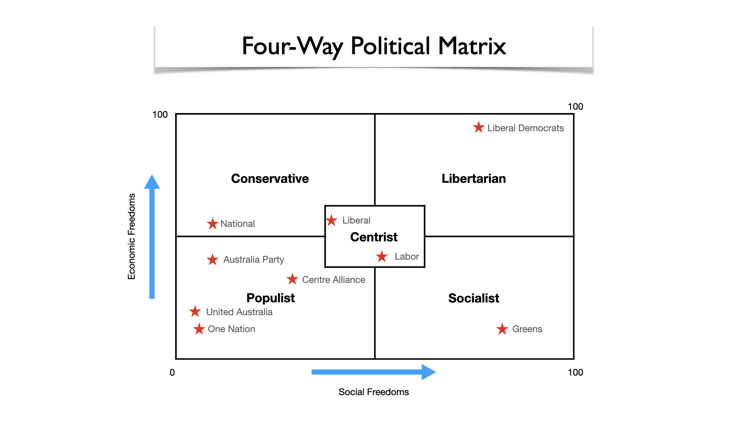

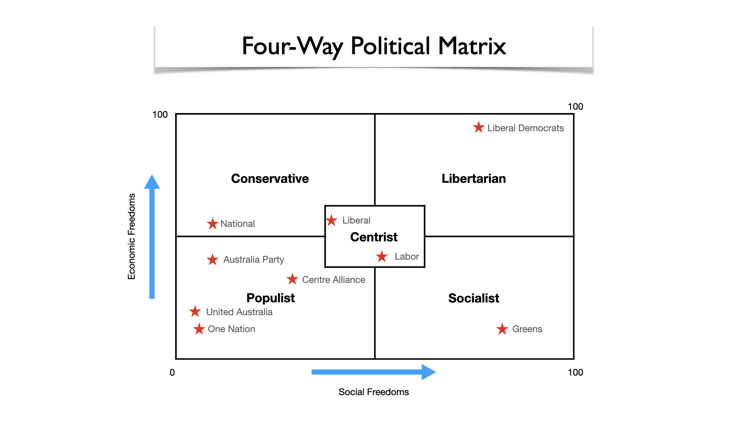

It helps in identifying political groups which are close to CL on some issues and thus potential allies, to have a more sophisticated way of positioning political parties than that provided by the traditional “left-Right” spectrum.

[See my posts on “Plotting Liberty: The Multi-Dimensionality of Classical Liberalism and the Need for a New ‘Left-Right’ Political Spectrum” (17 April, 2022) here and “The Spectrum of State Power: or a New Way of Looking at the Political Spectrum” (10 Aug., 2021) .]

I prefer a 4-way matrix like the following. It is my attempt to place Australian political parties in a matrix made up of “economic freedoms” on the y-axis and “social freedoms:” on the x-axis. There is a clustering of parties in the “Populist” quadrant, the “Centrist” position is populated by both the two major parties which are hostile to both sorts of freedoms, and there is only one party in the “Libertarian” quadrant which supports both kinds of freedoms. This shows how “interventionist” all the Australian political parties in fact are. The “Liberal” and Labor Parties are circling each other in the centre trying to attract the same set of voters.

Some Thoughts on Strategy

- I have indicated above which organisations might be the most appropriate ones to focus on these different groups of potential supporters of the ideal of liberty

- Given the small size of the CL movement in Australia it is important that we focus our limited resources according to a division of labour and expertise

- as my “Four-Way Political Matrix” shows, CL or libertarian political groups have more in common with “the left” on many social freedoms (gay rights, same-sex marriage, decriminalization of drug production/sale/use) than they do with “conservatives”; on the other hand they have more in common with populist groups who have a strong distrust in and dislike of traditional political elites and high taxes; and with the “Old” Liberal party when it came to deregulation and cutting taxes and when it has a so-called “Dries” faction which seems now to have become thoroughly “wet”.

- the tactic which a small group of CL elected representatives could adopt in Parliament is a version of Bill Clinton’s policy of “triangulation” where the CL politicians side with “the left” on social issues which promote liberty and with “the right” on economic issues which promote liberty.

Identifying those who are likely to be resistant to arguments for Liberty

I believe that there is a strong correlation between the ideas one holds and the interests one has, and that this connection cuts both ways. One’s interests often influence the ideas (and values) one holds – for example if one sees that there is easy money to be had by selling something to the government or getting a government privilege (like a monopoly or a protective tariff), then one quite likely has political views which support the right and duty of the government to provide these benefits and the obligation of taxpayers to pay for them, and to vote accordingly at election time. Conversely, if one has strong beliefs in the need for a powerful and interventionist welfare state one is probably inclined to work for an institution which makes this possible, such as in a government department dispensing welfare to the people, or in a university teaching students about the benefits of a welfare state and the evils of unregulated “capitalism”, thus one’s job provides one with an “interest” to protect, such as salary, retirement benefits, psychic satisfaction, and so on, which one will defend at the polling booth at election time.

Here is my list of those who are likely to be the most resistant to arguments for Liberty for the reasons given above:

- those who work for the state, such as politicians, senior bureaucrats, and their advisors; this group is commonly known as the “political class”

- another important group of people who work for the state are school teachers who work in the pubic schools

- those who benefit from the state, such as those who receive government privileges (subsidies, monopolies), and who receive benefits (welfare, pension) – the former are known as “crony capitalists”, the latter as the “dependent class” of welfare recipients

- those who are ideologically committed to a powerful state and large-scale government intervention in the economy, such as avowed socialists, Greens, Left wing academics and journalists (the ABC??)

Some Thoughts on Strategy

- The sad conclusion I have reached is that it may not be worth sacrificing our limited resources in appealing to most of these groups as they are made up of committed interventionists and statists who are adamantly opposed to free markets.

- some public sector school teachers (of economics, history, geography) might be reachable if they had alternative sources of information concerning the benefits of free markets (“capitalism”), the harms caused by state intervention, and the myths (both scientific and historical) concerning “the science” of catastrophic climate change; I do not know of any groups in Australia who are undertaking this important task of “re-educating the educators”; I have given some talks over the years to high school teachers and others about how they might better teach free market ideas to their students; I have done this via the Bastiat Society in the US [see some of my lectures here] as well as David Schmidt’s group at the University of Arizona – link. We need a branch of the Bastiat Society in Australia to find and reach out to people in the community who might be sympathetic.

- English high school teachers need to be provided with intellectual ammunition in order to defend the teaching of the classics or “Great Books”of the Western Tradition, which I believe has a very strong CL component within it [see my website]; I have been active for many years with the Association of Core Texts and Courses which is the professional association of college teachers of great books programs in the US; the Ramsay Institute has recently been set up in Sydney to promote the teaching of and learning about “Western Civilisation” which has been met with strong opposition from within the universities; I do not know if they have a program to reach out to high school teachers; so far they have largely ignored me in spite of many emails

- for decades Liberty Fund has organised small-group conferences (15 people) for academics who are sympathetic to CL ideas but who are “trapped” within very hostile academic institutions where they work on a day to day basis; many Australian academics have been fortunate to attend LF conferences both here (organised by Geoff Brennan) and in the US; there is nothing like that here in Australia and whether we have enough resources to do something similar for our academics is a moot point; I worked for LF for nearly 20 years building the Online Library of Liberty website to promote its publishing, conference, and Great Books of Liberty programs; it was getting millions of hits and downloads every year when I was summarily sacked in late 2019 and forced into early retirement.

The Impediments we Face in making the Argument for Liberty

The impediments we face in making the case for a more liberal society have been created by a combination of economic “interests” and false thinking (the “ideas” which they hold). Those who earn a salary paid for by taxpayers, enjoy a subsidy or monopoly, receive a welfare benefit, and so on will be very reluctant to relinquish these if a true CL party ever came to power and began dismantling the welfare/administrative state. People are likely to dismiss the intellectual arguments for a free market out of hand if they have deeply held misunderstandings about the benefits of free markets and the harms caused by government intervention. Thus, the combination of having a vested interest in the continuation of the status quo, as well as having false ideas about the government and free markets, is a very potent obstacle to the creation of a free society.

Some of the beliefs that people hold (both people in government as well as the voters) about the legitimacy of what the state does and what the people who work for the state do to deserve their position, are as follows:

- the state and the people who work for it are doing good things for society at large that would not be done at all if left to the market (public goods, HEW)

- that the free market (capitalism) is a dangerous rapacious force which tends towards monopoly and exploitation unless held tightly in check by the government and the regulatory state

- that although the state can make “mistakes” they are minor compared to the harms caused by “unfettered capitalism” and can be controlled by good people working within a well-intentioned government and bureaucratic structure

- that things can continue as they are, or continue to steadily improve indefinitely, with more government and bureaucratic intervention when necessary, regardless of the tax burden on tax payers, the regulatory burden on producers, and the financial burden on everybody caused by government borrowing and artificially low interest rates.

The following is a list of four key ideas which I think are common to many if not all forms of justifications for state control and intervention in the economy and in people’s lives in general; the morality of using coercion, overstating the extent of “market failure”, ignoring the extent of “government failure”, and the widespread ignorance of economic principles. To undermine or refute any one of these key ideas would, I think, take us a long way to persuading people to rethink their faith in government intervention in our lives:

- the morality of using coercion: traditional CLs (both “radical” liberals and “moderate” liberals in my terminology) believe that the initiation of the use of coercion against individuals is immoral and should be banned (note: some “modern” liberals reject this view as too “absolutist” and accept a considerable use of coercion by the state as an unfortunately “necessary evil” but this should be kept to an minimum if possible). Most people however see the state’s use of coercion as not only necessary but just if certain socially desirable results are to be achieved – this is the policy of “expediency”. Most people also do not see the actions of the state as coercive in the first place. To them, the coercive “iron fist” of the state is not visible – which leads me to conclude that here we have, to rephrase Adam Smith, the problem of “the invisible fist” of the state. This widespread belief has resulted in what I call “the normalisation of state coercion”. By this I mean the acceptance by the vast majority of the people that the use of state coercion is normal, necessary and inevitable in order to solve our social and economic problems. They thus hardly ever question this belief and demonstrate strong opposition when CLs/libertarians do question it.

- the frequency of market failure – there is a widespread belief that the market has inherent flaws which inevitably lead to serious problems unless “corrected” by government action (i.e government coercion). These “market failures” are typically thought to be things like the monopoly and predatory power of large corporations, the boom-bust economic cycle, environmental “degradation” caused by any industrial activity, and the inability to provide all kinds of “public goods”.

- ignoring the extent of government failure – the theoretical counterpart to the concept of “market failure” is the notion of “government failure” which is largely ignored; there is a near universal belief that governments and “experts” (technocrats) employed by the government can solve problems, “manage” the economy, and provide services which private individuals cannot; this belief has been maintained in spite of the many disastrous attempts by government in the 20th century to “plan” or “manage” the economy, and the theoretical work of the Public Choice school of economics, whose insights are almost universally ignored by the economics profession

- there is near universal public ignorance of basic economic insights which makes points 2 and 3 possible; for example, that there are opportunity costs for every economic decision one makes; that there are “the seen and the unseen” consequences of economic actions (especially government intervention in the economy); the idea that every action has a cost and a benefit which is different for different people and groups; the inevitability of “unintended consequences” of government regulations, and so on

Some Thoughts on Strategy

- making visible “the invisible fist” of the state – it should be the role of journalists to expose the true nature of state regulation by showing how those regulated and those who oppose this regulation are in fact coercively treated by the state and its officers; some coercive acts by the police were brought to our attention during the almost fascist lockdown in the state of Victoria last year, but it was largely ignored by the public (which in itself, shows the depth of the problem CLs face); the problem then is for us to find those journalists who are sympathetic to the free market, cultivate and encourage their work, and to educate them further in sound thinking about liberal political economy

- making the moral case that the use of coercion is wrong – in the 19thC in Britain there was widespread popular belief in moral principles such as “self help” and “minding one’s own business” and leaving others free to go about their business, as well as the utter immorality of slavery; this provided the moral backbone to the broader liberal movement of that period; we need to cultivate a similar set of moral principles in Australia but how this might be achieved in a moot point; such moral principles used to be part of dissenting church doctrine like the Methodists and the Quakers; however, most churches today preach a version of “the social gospel” which in my view is a form of socialism not liberalism;

- teaching the public about basic economic theory – especially concerning the benefits of the free market, the harms of government intervention, the myths about “market failure”, and the pervasiveness of “government failure; we need something like an Australian version of the “Bastiat Society” organised at the grass roots level to help teachers, self-employed people, and professionals learn more about economic ideas; if we were looking for the Australian equivalent of Bastiat we might look at William Hearn (1826-1888) the first professor of economics at the University of Melbourne, who was in fact a follower of Bastiat, or Bruce Smith (1851-1937) who was a member of the NSW Parliament and a radical liberal [I have put some of their work online at my personal website]; Bastiat made a name for himself by writing short articles for newspapers in an attempt to expose the fallacies of economic thinking which were widely held by the public and government officials; we need something similar today – a good modern example of someone working in the tradition of Bastiat are the “letters to the editor” written by Don Boudreaux at the Café Hayek) website.

Conclusion

The above comments paint a rather bleak picture of the threats which face the liberty movement and the enormous difficulties which we face in trying to resist them. I will conclude by saying that my recommendation is that we in the liberty movement should constantly stress the following two points, namely to emphasize the benefits of liberty to both individuals and the communities in which they live, and the harms caused by the use of state coercion and intervention.

One might hope that if these alternative visions of the benefits of liberty and the harms of state coercion can be presented to enough people in a form they find appealing and persuasive, then we in the liberty movement might be more confident about the future of liberty.

.

.