[The British Atlas holding up the Political Establishment.]

Note:

- This is part of a collection of posts on “The Current State of Liberty and the Threats it faces”.

- This is part 2 of a two-part post on “The Big Picture”. See part 1

7.) We need to show the public in a more convincing way the very considerable achievements of CL over the past 200 years

We need to show the public in a more convincing way the very considerable achievements of CL over the past 200 years. The achievements of CL have been enormous since CL first began challenging the Old Order of the monarchical/absolutist state (Throne) and the established church (Altar) in the 17th century, with most of its successes coming in the late 18th century (the American and French revolutions) and their aftermath in the 19th century.

These achievements can be summarized as the Great Emancipation, and the Great Enrichment. As a result of CL reforms and revolutions much of western Europe, America, and the English colonies were emancipated:

- from coerced labour such as slavery and serfdom (abolition)

- from the arbitrary authority of kings and princes (constitutional limits to state power, the rule of law, freedom of speech, low taxation)

- from “cruel & unusual punishment”, such as torture, the death penalty, arrest without court order, imprisonment without trial (trial by jury, independent judiciary, habeas corpus, punishments which “fit the crime”)

- from violations of property rights (legal protection of property, enforcement of contracts)

- from the arbitrary power of the Church (freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom from paying compulsory tithes)

- from restrictions and bans on associating with others on a voluntary basis (marriage and divorce laws, private clubs and associations (“civil society”))

- from restrictions on trade and industrial activity (free trade and deregulation, freedom to enter and practice a profession or trade)

- from restrictions on the movement of people, goods, and capital (freedom to move within the country, freedom to emigrate, free trade)

- from strict limits on who could participate in political activity such as voting and standing for election (democracy, freedom of association, freedom of speech)

- from war and conscription into the army (peace, low taxes and debt, laws of warfare, international arbitration)

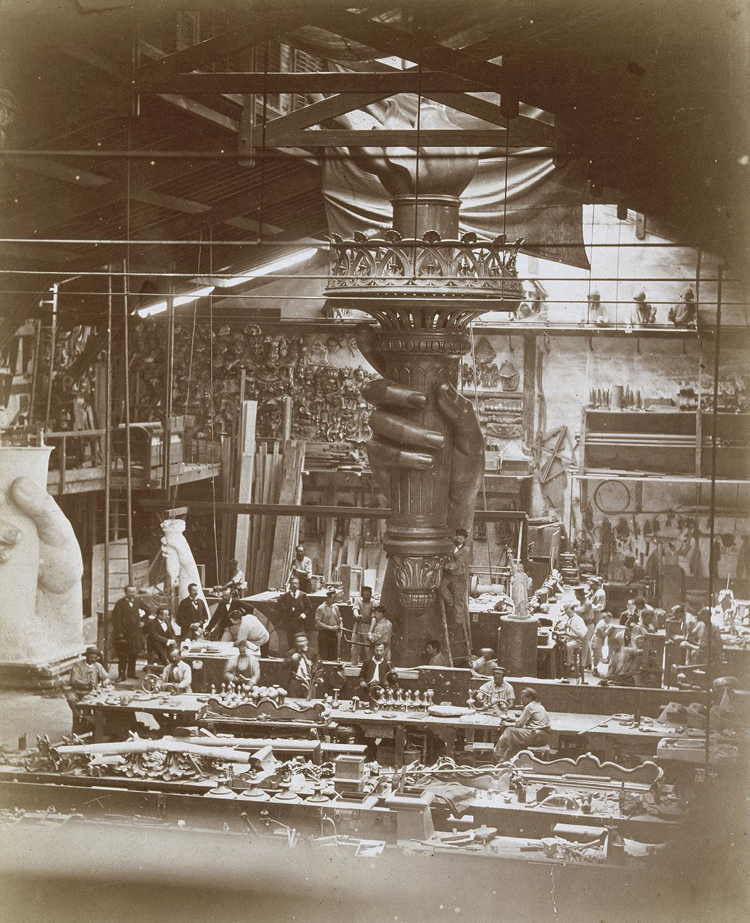

The great emancipation led directly to an explosion of wealth creation (market driven innovation, greater productivity of free production and free trade) which in turn led to longer life expectancy, lower infant morality (and childbirth deaths of mothers), reduction of disease, less demanding physical labour (mechanization), and greater home comforts for the first time in human history, especially for ordinary working people (piped water, sewers, heating, light). Although these emancipations and enrichment completely transformed European and American society and laid the foundation for our modern world they were left incomplete and unfinished, and, as a result, other ideologies less friendly, even very hostile to CL, have become dominant (socialism, welfare statism, fascism/populism).

Also see these related posts:

- “A Balance Sheet of the Success and Failures of Classical Liberalism” (21 Apr. 2022) here

8.) We need to be honest with ourselves about the failures of CL and the incomplete nature of the “liberal emancipation project”

We need to be honest with ourselves about the failures of CL and the incomplete nature of the “liberal emancipation project”. In spite of the considerable successes of the liberal “emancipation project” and the ensuing “great enrichment”, much was left undone, unfinished, and incomplete, which left the political and intellectual door open for other political ideologies to step in. These competing ideologies which replaced liberalism were nationalism and “social democracy” (interventionism), both of which had moderate and more extreme (i.e. violent and coercive) versions. These failures can be summarized as the inconsistent application of basic liberal principles, some complacency about the inevitability of liberal reform, several weaknesses or gaps in economic theory to explain certain problems, considerable political naïveté, and the loss of what had once been an inspiring liberal “vision” of the kind of society they wanted to create.

The emancipation project was left incomplete. This was a result of the inconsistent application of basic liberal principles to all members of society. The most glaring examples of this were unequal economic and political rights for women, indigenous people or ex-slaves, and gays and lesbians. Furthermore, the fact that there could be a group who could call themselves “liberal imperialists”, given the violence and privilege inherent in they way in which colonies and empires were created and maintained, suggests liberalism was changing into something which would soon become unrecognizable to its radical and even moderate founders. There was also a strong attitude of complacency about how the liberal project would continue as a result of the inevitable “evolution” of societies and institutions to an ever more “advanced” and liberal form. Why should liberals struggle to spread liberal ideas and practices if “evolution” would do this for them? and why even bother when it came to the “inferior” races and cultures who were literally the “subject” of the European Christian “civilizing mission”?

CL political and economic theory suffered from several weaknesses or gaps which made it difficult to understand or solve certain problems. We have already mentioned the problems posed by exaggerating the extent of and misunderstanding the reasons for “market failure”, and the related problem of ignoring the extent of and reasons for “government failure”. These theoretical problems would only be explained by developments in liberal political economic theory in the 20th century with the emergence of the Austrian and Public Choices schools of economic. Perhaps the most serious theoretical problem for CLs was their inability to offer a good explanation for the repeated occurence of the business cycle with its boom and bust, with the latter causing economic depressions and so much suffering for the poor and working classes. This theoretical failure meant that alternative theories such as the “new liberal” theory of “underconsumption” (Hobson) or the Marxist theory of the inevitable collapse of capitalism as monopoly and ruthless competition destroyed it from within, became increasingly attractive to workers, intellectuals, and politicians.

A more “political” weakness in CL theory was the tendency to view “democracy” as an end in itself rather than as a means to achieve other liberal ends such as the protection of life, liberty and property, and holding elected politicians accountable for their behaviour. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries liberals, especially republican liberals in America, saw democracy as a means of removing entrenched political elites who used the political system for their own ends at the expense of “the people” (i.e the ordinary working and tax-paying people). However, gradually democracy as a “process” came to be regarded as desirable in itself, and that it should be applied to more and more aspects of social and economic life. The end result would be a system where the “will of the people” should be consulted before any group decision could be made concerning every or nearly every social and economic arrangement individuals might wish to engage in.

At a more theoretical and philosophical level, we have the weakening and eventual abandonment of a belief in natural rights as the proper grounds for believing in “the right” individual had to their life, liberty, and property, and to be left alone by the government to exercise these rights, so long as they respected the “equal right” of others to their life, liberty, and property. By the late 19thC the theory of utilitarianism (Bentham, James Mill, and J.S. Mill) had replaced the natural law / natural rights perspective, with the added twist that utilitarian-minded politicians and bureaucrats could and should decide what activities or policies “maximized” a society’s “utility” or “happiness”, even if this meant taking or regulating the life, liberty, and property of some, if it could be “shown” that doing so would increase the total amount of utility / happiness of the majority. The end point would be reached when people believed that if individuals had any “rights” at all, they were the creation of “the government” or “the law” and thus were not an inherent part of what it meant to be a human being, and did not exist prior to the formation of government. Thus, these “rights” could be suspended or revoked at any time based upon the assessment of politicians and bureaucrats that in doing so the “welfare of the people” would be served. We saw this clearly during the Covid19 lockdowns and bans on travel, association, and commercial activity throughout the western world during 2020-22.

Many CLs were politically naive by placing considerable faith in the benevolence and omniscience of the state and its officials to solve pressing social and economic problems. [See the section above on “government failure” for details.] They expressed a similar faith in the ability and willingness of the “middling class” to make democracy work once they were granted the right to vote (after 1832 in Britain). Many CLs had doubts about the ability of the working class to behave “responsibly” if they were given the right to vote given their lack of education, “fickleness”, and susceptibility to being bribed by ruthless politicians. However, as democracy matured during the course of the 19thC it became clear that the middle class behaved exactly the way they had previously thought the working class would behave: they were easily misled and deceived by ruthless politicians, they voted for politicians who promised to give them “something for nothing,” and many from their ranks actively sought out other benefits from the state by lobbying for jobs and contracts. The net result is what we see today, the new democratic state was “captured” by vested interests, both old established groups who learned to adapt to and manipulate democratic institutions, as well as the newly enfranchised groups (business organisations, trade unions).

One reason why the newly enfranchised groups behaved this way was their ignorance of basic economic principles. Some of the liberal political economists tried to rectify this problem by attempting to explain basic economic ideas simply to the ordinary person via articles in the press. The most notable example of this was Frédéric Bastiat during the 1840s with his dozens of articles in which he debunked the “economic sophisms” commonly used to defend tariff protection, subsidies to industry, and handouts for the people. He failed in this task then, just as CLs today have failed to educate the public about these very same issues. Sometimes I feel that we have been trapped in a kind of “ideological Groundhog Day” where we have to keep repeating day after day the same arguments for liberty and against government intervention with no apparent success.

The “Loss” of the Intellectuals to Socialism. The group which might have persuaded the ordinary person of the moral and economic benefits of free markets were the “intellectuals”. However as the 19th century wore on the intellectual class increasingly moved away from CL and adopted socialist, nationalist, or other statist beliefs instead. Why the CL movement “lost” the intellectual class to socialism and statism in the late 19th century, and which still continues today, is an important question which modern day CLs still have to find an answer to and a way to reverse the situation. A common response is that the uncertainties of making a living in a free market where one’s work is only rewarded if consumers value your work enough to voluntarily pay for it, drove intellectuals into the apparently more certain and predictable arms of the state which provided them with secure jobs in the administration or the state funded academy. Another explanation is that intellectuals adopted the old aristocratic disdain for “productive labour” and did not want “to dirty their hands” with commerce. Why this was the case is unclear.

CLs lost their “Vision” of what a free society should be like, why this was desirable, and thus “lost” the moral high ground to the socialists and statists. Their loss of vision made their ideology less attractive to the young, who found an alternate and more attractive and inspiring vision in socialism/Marxism, nationalism, and fascism, and now environmentalism. One of the reasons why radical liberals in the late 18th and early 19th century were able to put forward an inspiring vision of what emancipation might achieve, and thus attract many people to the CL cause, was their passionate sense of justice, or rather their hatred of the injustice which they could see all around them. This passion came out in their polemical writing, best exemplified by Thomas Paine whose “Common Sense” (1776) and “The Rights of Man” (1791) inspired CLs on both sides of the Atlantic. Who in the late 19th century was writing similar inspiring essays to attract a new general of young people to CL? Very few – perhaps only the aging members of the last generation of “old liberals” like Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) and Auberon Herbert (1838-1906). This loss of “vision” was pointed out by Friedrich Hayek, James Buchanan, Murray Rothbard, and Robert Nozick in the second half of the 20th century, and again by Richard Ebeling and Peter Boettke in the 21st.

Also see these related posts:

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future I” (27 August, 2021) here

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future II: The Contribution of Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)” (29 Aug. 2021) here

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future III: Liberal Experiments, Frameworks, and Archipelagos” (11 Oct. 2021) here

- “Hayek on a Liberal Utopia” (11 Sept. 2021) here

9.) We need to be clear eyed about what still needs to be done if we truly wish to complete this great “liberal emancipation project” FOR ALL PEOPLE

We need to be clear eyed about what still needs to be done if we truly wish to complete this great “liberal emancipation project” FOR ALL PEOPLE. In my view CLs need to do the following things:

To complete the liberal “emancipation project” for all individuals. The “great emancipation” seemed to have stalled sometime in the late 19thC before its work had been completed. We need to restart the engine and make sure this time it gets applied to all groups equally, regardless of gender, race, or nationality.

To remove all the remaining impediments to the full flowering of “the great enrichment”. Similarly, the other great project of CL reform and betterment, the “great enrichment,” has stalled in the west (especially in Europe) and is hampered in other parts of the world by the clumsy and heavy handed approach taken by interventionist governments in places like India and China. We need to remove all the remaining impediments to the full flowering of “the great enrichment” so that all people everywhere can benefit.

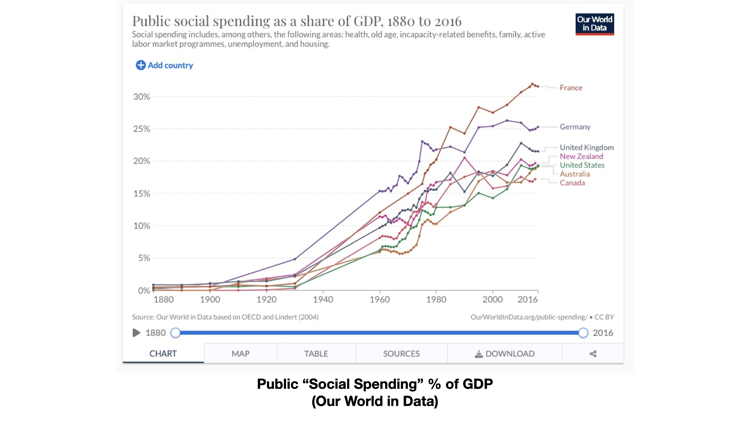

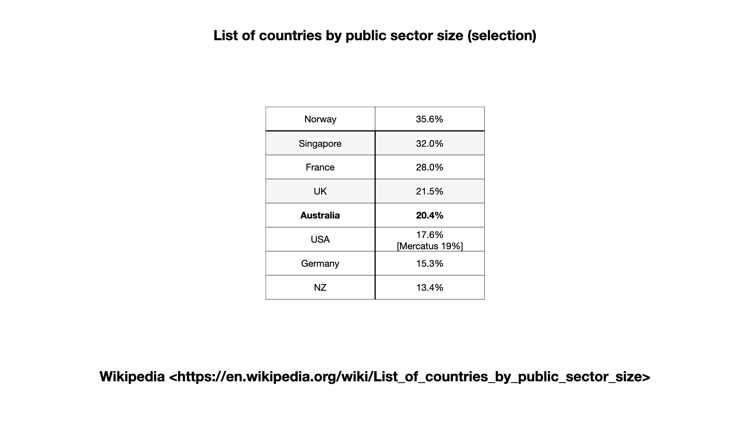

To remove the institutional incentives which encourage predation (both private and public). We need to reform or abolish political institutions in order to remove the incentives which encourage “predation” – both public and private. The great temptation for “predators” of all kinds is the enormous wealth which the state controls and can dispense to the well-connected few, or the most vocal voter blocks during election campaigns. To remove the temptation we need to cut the resources which the state can dispense, this means drastically cutting taxes and the size and power of the administrative and welfare state.

To challenge the ideological arguments used to legitimize / justify this predation and redistribution of wealth. These arguments are put forward by academics, intellectuals, and the press, and are widely shared by educated people. CLs need to offer counter arguments (which they have done for a couple of centuries) and to present them in a way which will win back the intellectual class to the cause of liberty. How best to do this is open to discussion.

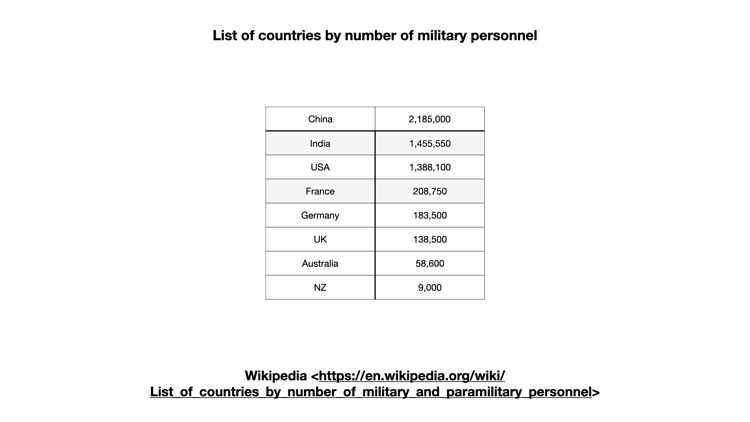

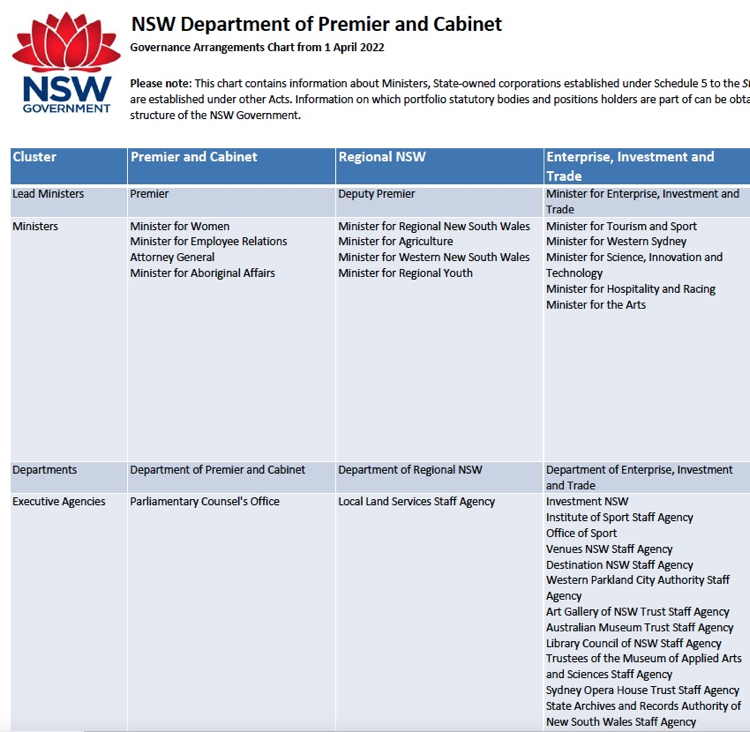

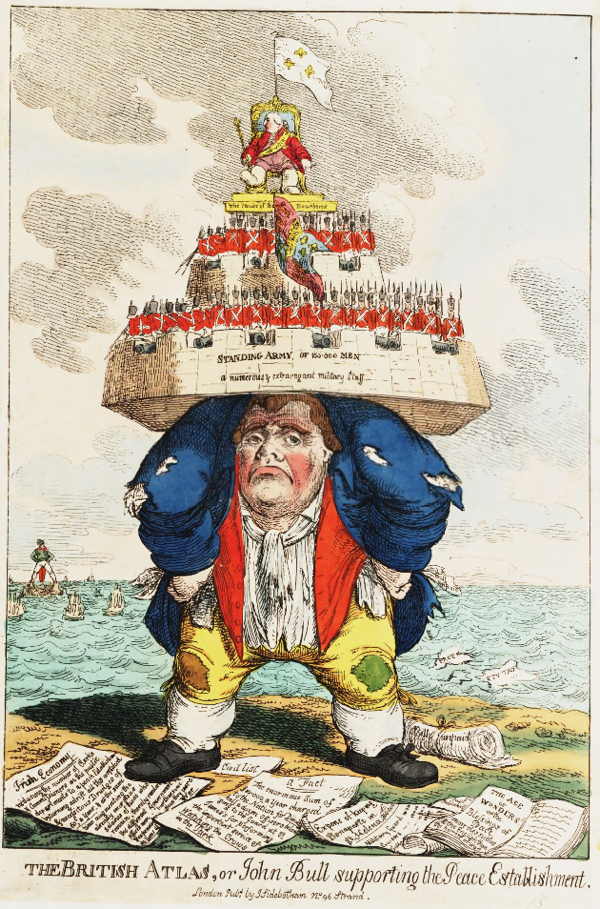

To find a solution to the serious political problem of dependency on the state. This dependency has taken the form of the large number of people who work directly for the state (“civil servants”), those individuals and firms which sell their goods and services to the state, those individuals and firms who have been given special privileges or monopolies from the state in order to earn a living, and those who are dependent on state transfer payments to survive (pensions, medicare, income support, unemployment benefits). Because so many people have now become dependent on, or beneficiaries of, the modern state the return to Liberty in a democracy has become a very difficult, perhaps impossible task. A tipping point of “no return” may well be reached when the number of voters who are dependent on the state for all or a large part of their income is greater than 50%. This will means that it becomes increasingly difficult for a CL party to persuade voters to cut or end their own source of income and financial support.

Conclusion

My quite depressing, but I think realistic, conclusion is the following:

1.) There has been a collapse / failure of the Liberty movement in the 20th & 21st centuries (both ideologically & politically). The rot within CL became apparent towards the end of the 19thC with the emergence of a “new liberalism” which accepted the need for the creation of a large and powerful welfare and regulatory state. After a period of near total eclipse of the Liberty movement during the Thirty Years War of the 20thC (1914-1945) there was an attempt to revive CL (the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947) which had some limited political success in the 1970s and 1980s (Thatcher and Reagan) before petering out. All so-called “liberal parties” today are dominated by “neo-liberals” whom I believe are “no-liberals” at all, i.e. they are LINOs (liberal in name only). Both the major blocks of political parties all support a form of “social democracy”, i.e. a form of “socialist” or “interventionist” democracy.

The revival of CL has been more marked in the ideological realm, where we have never seen so many CL scholars, intellectuals, and policy analysts and activists, which bodes well for the future. The problem seems to be the mismatch between the ideological growth of CL on the one hand and political failure of “liberal” parities (or advocates of Liberty within these existing parties) on the other hand.

2.) The rise of the modern warfare / welfare / regulatory / Keynesian / surveillance / hygiene state is unprecedented and seemingly unstoppable. The nearly universal “first response” of voters and governments to “crises” (whether real or manufactured) is to call for the government “to do something”. There is a majority who believe in the legitimacy and ability of “experts” to provide solutions to these crises and to implement them by any means possible. Far too many of those who expressed support for free markets and individual liberty abandoned their liberal principles and joined the statist band-wagon, thus severely weakening the Liberty movement. The most recent “crises” I have in mind are the terrorist attacks of 9/11 2001, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (2001, 2003), the Global Financial Crisis 2008, the Covid19 panic and lockdowns of 2019, and the ever growing “Global Climate Catastrophe”.

3.) So many people have become dependent on, or beneficiaries of, the modern state that the return to Liberty is a very difficult, perhaps impossible task. In democracies like ours we are seeing the convergence of two forces which work in favour of the state and its power. The first is ideological, where a majority of the people are hostile to free markets and support government intervention; the second is political, where a very large percentage (perhaps eventually a majority) of voters are dependent on the state for all or most of their income and act politically (electorally) to protect this interest. When the two forces pushing to maintain or expand the power of the state meet, CLs face a very, very difficult task if they wish to reverse course.

4.) There are serious practical / political problems in creating a “limited (protective) government” and then keeping this government truly “limited” over time. I believe this is a problem CLs have not faced up to adequately in the past and still do not have a satisfactory solution. The history of the Liberty movement shows us that there have been successful efforts to turn a big “predatory” State into a limited “protective” State. [See above for specific examples.] However the events of the 20thC and the first two decades of the 21stC have also shown us how a “limited government” can slowly but steadily become increasingly “unlimited”. This process of the expansion of state power is the result of another convergence of interests: the demands of the electorate, lobby groups, and rent-seekers who want government solutions to their problems, and the ambitious and self-interested behaviour of politicians and bureaucrats who step forward to provide these solutions and advance their careers at the same time. The traditional response of CLs has been that the power of the state can be kept in check by the following four things:

- constitutional limits on the actions of the state,

- a vigilant high or constitutional court to enforce these limits,

- a vigilant free press to expose and denounce those who violate these limits to power, and

- a vigilant and informed electorate who will vote to protect Liberty.

I think the course of the last century has shown how weak these four components to limiting the power of the state have been. “Vigilance” seems to have turned into “negligence.” How these limiting forces might be revived , or replaced by something else, is moot.

Atlas may eventually shrug, or he may not. Only time will tell.