[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

Introduction

Following the rise to power of Louis Napoleon, who declared himself Emperor Napoléon III in 1852, the radical French CL and political economist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) gave a lecture at the Musée royale de l’industrie belge in October 1852 on “Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériel” (Revolutions and despotism considered from the point of view of material interests). In this lecture he declared that it was the function of economists to be “les teneurs de livres de la politique” (the bookkeepers of politics) who should periodically draw up a balance sheet of the “profits and losses” or the “costs and benefits” of political activity. In his case it was the impact of the French Revolution in 1789 and another revolution on February 1848. [For the details of his political “bookkeeping” see my essay “Gustave de Molinari on Economists as the Bookkeepers of Politics: ‘Unfortunately, No One Listens To Economists’.” (23 April, 2020). Online.]

I want to do much the same here, but this time to draw up a list of the costs and benefits of a political and economic ideology, or rather the “successes” and “failures” of Classical Liberalism (henceforth “CL”). My conclusion is that the very considerable “benefits” or achievements of CL have not been recognized as they should have been, and that modern day CLs and libertarians have not adequately recognized and discussed the very obvious costs or “failures” of their tradition. What they can do to address the latter is a matter still to be resolved.

The Achievements of Liberalism

The achievements of CL have been enormous since CL first began challenging the Old Order of the monarchical/absolutist state (Throne) and the established church (Altar) in the 17th century, with most of its successes coming in the late 18th century (the American and French revolutions) and their aftermath in the 19th century.

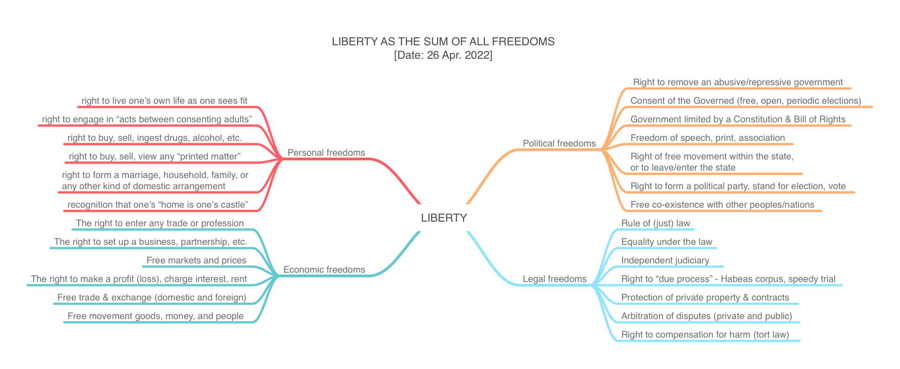

These achievements can be summarized as

- the Great Emancipation, and

- the Great Enrichment

The Great Emancipation

Richard Ebeling has called this movement the CL “crusades” for liberty and Peter Boettke “the emancipation project”. This freed millions of people from the bondage (Boettke’s word) of the Throne (the monarchy), the Altar (the established church), the Sword (the military), Slavery and Serfdom (the large land and plantation owners), the Plough (pre-industrial agriculture), and the Mercantile interests.

See the following posts for more information:

- “Classical Liberalism as a Revolutionary Ideology of Emancipation” (13 Oct. 2021) here

- “Classical Liberalism as the Philosophy of Emancipation II: The “True Radical Liberalism” of Peter Boettke” (17 Oct. 2021) here

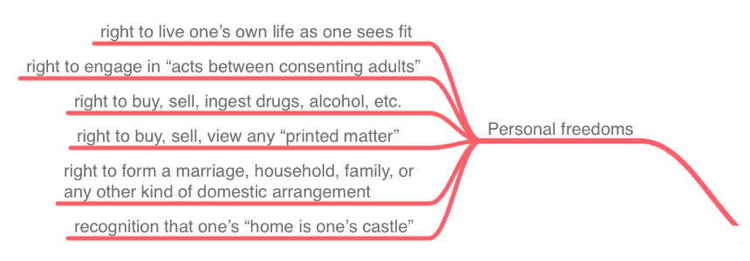

My list of “emancipations” is a compilation and expansion of Ebeling’s and Boettke’s lists. As a result of CL reforms and revolutions much of western Europe, America, and the English colonies were emancipated:

- from coerced labour such as slavery and serfdom (abolition)

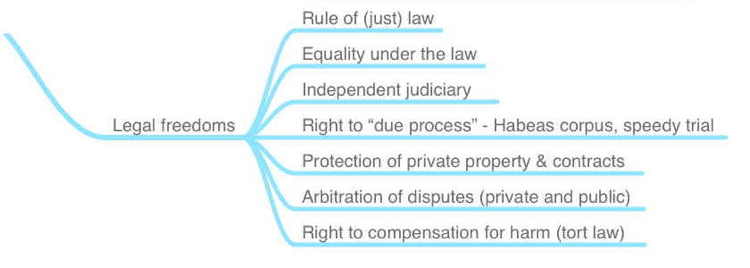

- from the arbitrary authority of kings and princes (constitutional limits to state power, the rule of law, freedom of speech, low taxation)

- from “cruel & unusual punishment”, such as torture, the death penalty, arrest without court order, imprisonment without trial (trial by jury, independent judiciary, habeas corpus, punishments which “fit the crime”)

- from violations of property rights (legal protection of property, enforcement of contracts)

- from the arbitrary power of the Church (freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom from paying compulsory tithes)

- from restrictions and bans on associating with others on a voluntary basis (marriage and divorce laws, private clubs and associations (“civil society”))

- from restrictions on trade and industrial activity (free trade and deregulation, freedom to enter and practice a profession or trade)

- from restrictions on the movement of people, goods, and capital (freedom to move within the country, freedom to emigrate, free trade)

- from strict limits on who could participate in political activity such as voting and standing for election (democracy, freedom of association, freedom of speech)

- from war and conscription into the army (peace, low taxes and debt, laws of warfare, international arbitration)

Note: There were many aspects of life in the 19th century which were never regulated by the state in any systematic manner, such as private activities such as prostitution, or the production, sale, and consumption of alcohol and drugs. It would only be in the 20th century, when liberal ideas and institutions were severely weakened that the state began to prohibit, sometimes ruthlessly, so-called “victimless crimes” like prostitution, alcohol, and drugs.

The Great Enrichment

This is Deidre McCloskey’s term and she has documented how the great emancipation led directly to an explosion of wealth creation (market driven innovation, greater productivity of free production and free trade) which in turn led to longer life expectancy, lower infant morality (and childbirth deaths of mothers), reduction of disease, less demanding physical labour (mechanization), and greater home comforts for the first time in human history, especially for ordinary working people (piped water, sewers, heating, light).

For a summary of her findings see this article:

Deirdre McCloskey, “The Great Enrichment” Discourse (July 13, 2020 here

and note the accompanying table showing the extraordinary increase in wealth which 1.4 to 2% annual growth can achieve:

The argument is that this modest annual growth was made possible for the first time in human history, and was only possible at all, because of CL reforms in ideas, behaviour, and institutions.

It is important to note that an important pre-condition for the Great Enrichment” was a change in thinking about the merits of productive labour. Traditional elites considered productive labour undertaken by themselves to be demeaning to one’s social status, thus one needed servants, serfs, and slaves to undertake the actual hard work to create wealth. For most of human history the ideal elites sought to copy was that of the warrior or the aristocratic land owner with the time and leisure and wealth to pursue “higher” ends. The sea change which made the Great Enrichment possible was for more and more people to see that productive labour (including running a business, engaging in trade, selling goods and services to ordinary consumers) was a “noble” activity in itself and that all impediments to such activity should be removed. This applied not just to others but also to oneself and one’s children, that it was no shame to “go into trade” as it was called. For example, a key indicator of how these ideas about labour had changed during the course of the 19th century in Britain was the number of “beer barons” who were awarded knighthoods and earldoms by the British monarchy.

The Failures of CL

Although these emancipations and enrichment completely transformed European and American society and laid the foundation for our modern world they were left incomplete and unfinished, and, as a result, other ideologies less friendly, even very hostile to CL, have become dominant (socialism, welfare statism, fascism/populism).

1.) The emancipation project was left incomplete with some groups left out or ignored (women, gays, indigenous people). This was due to a number of factors:

- the inconsistent application of liberal principles by believing that not all human beings had equal “rights” to life, liberty and property, or that if they had these rights they were already “protected” by their “guardians”, whether they be their husbands, fathers, or more “advanced” white men;

- complacency on the part of many CLs who believed that the continuation of the liberal project was “inevitable” as it was part of an unstoppable evolutionary process, or

- their religious arrogance since they believed that they had undertaken a Christian “civilizing mission” to bring God and liberal order to the colonies.

The exclusion of these groups opened the door for other political and economic ideologies to step into the gap left by the CLs and to offer an alternative route to their eventual emancipation by means of much greater state intervention.

2.) CL political and economic theory suffered from a series of weaknesses which made it vulnerable to criticism and being replaced by other ideologies which seemed to be able to offer explanations and solutions to current problems. These other “solutions” usually involved much greater state regulation and control of both private life and the economy. Some of the theoretical problems within CL theory included:

- viewing “democracy” as an end in itself rather than as a means to achieve a higher end (such as removing the power and privileges of the old elites, making politicians and government agents accountable “to the people”, placing strict limits on the power of the state; instead, democracy came to be seen as an end in itself which was applicable to larger and larger areas of human activity, such as economics, thus giving rise to the idea of “social democracy”

- the weakening of belief in natural rights as the foundation of liberty (which had radical implications) and its replacement by utilitarianism which was a far weaker defence of liberty in that it allowed many exceptions based upon bureaucratic and political calculations of “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” principle

- exaggerating the extent of and misunderstanding the reasons for “market failure” which led to the belief that the government (regulation) should be used to rectify these failures; the older “presumption of liberty” as the guiding principle of government policy was replaced with “the presumption of government intervention” to solve problems

- ignoring the problem of “government failure” by overestimating the ability of the state to regulate economic matters; the reasons for this failure of government would not be fully appreciated until the work of Mises and Hayek in the 1920s and 1930s (the problem of rational economic calculation under socialism, the problem of knowledge), and Buchanan and Tullock in the 1960s (the self-interested behaviour of politicians and bureaucrats)

- not being able to explain the cause of the business cycle and the economic depressions which were the result which hurt the working class and seriously disrupted industry and commerce; again, this problem would not be fully understood until Austrian economists (Hayek and Mises) developed their theories of the connection between the expansion of the money supply by governments, the “malinvestments” which this caused, resulting in a series of inevitable “corrections” and the repricing of goods.

3.) Many CLs were politically naive in thinking that coercion by the state was an acceptable means of pursuing liberal ends. The “new liberals” especially came to see the state not as a “necessary evil” but as a “positive good” for the spread of emancipation and enrichment. This “political naïveté” took several forms, such as

- their faith in the benevolence and omniscience of the state and its officials; CLs recognized that “private predation” undertaken by powerful private interests such as privileged landowners, manufacturers, merchants, and bankers and financiers had been a serious problem and was therefore the focus of many early CL reforms (abolition of serfdom, tariff protection, subsidies to favored industries), but they did not also recognize that “public predation” by the new democratic state itself was becoming a serious problem as well. To put this problem in the language of Public Choice (Buchanan and Tullock) it was naive of CLs to think that those who “make the rules of the game” (the members of Parliament) should also “referee the game”, and even “play in the game”. They too had their own vested interests which included the desire to wield power, to enjoy the “perks of office”, and to be re-elected.

- their willingness to let the new democratic state be “captured” by vested interests (both old and new); the new democratic state provided a mechanism for powerful political and economic elites to continue their predatory behaviour under cover of “national development” or “national security”; some of these elites were new, such as the newly wealthy and ambitious leaders of industry and commerce who sought the reintroduction of tariffs in the late 19th century, or supported the arms race as it provided large contracts for ship building among other things; others were members of the old elite who came from traditionally privileged groups who had benefited from the old order, such as wealthy landowning families who traditionally staffed the courts, the military, and the colonial administration; a third group were made of intellectuals who staffed the new bureaucracies which administered the expanded activities of the state in areas such as public works, transport, education, health, and welfare.

- their faith in the ability and willingness of the “middling class” to make democracy work; the argument was that an educated and morally upright middle class would make sure that the new democratic state would remain very limited in its powers, that it would only ensure that “the rules of the game” (the protection of life, liberty, and property) were adhered to and that the state would do nothing else; related to this idea was the notion that as the “working class” became more affluent they would come to share the values of the liberal middle class and would do likewise; what became apparent was that all social and economic classes wanted to use the power of the state to grant themselves privileges at the expence of others; this is what Bastiat described as the definition of the modern state:

> “L’Etat, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde” (The State is the great fiction by which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else) “The State” (JDD, 25 Sept. 1848) (CW2, p. 97)

4.) The inability to explain basic economic ideas simply to the ordinary person: this has been a long standing problem for CLs going right back to its origins; this is because many economic insights are not self-evident as they require a longer term perspective to appreciate (that a small amount of growth p.a. can lead to a doubling of income in a generation); that the results or consequences of government intervention cannot be seen immediately (Bastiat’s notion of “the unseen”) but emerge over time (such as shortages), whereas a government subsidy, price control, or welfare payments can be seen immediately (Bastiat’s “the seen”); that some incentives (or disincentives) can be rather subtle, as with Smith’s idea that the self-interest of a producer might lead as though an “invisible hand” were at work, to improve the well-being of society as a whole. So long as people acted on moral principles (that it was wrong to seek and get government handouts or privileges) then they did not need to know the finer points of economic theory to realize that government intervention was not a good thing; however, as this moral belief waned, they needed to understand the other, more technical and theoretical reasons to avoid government intervention, and this understanding they did and still do not have.

5.) The “Loss” of the Intellectuals to Socialism: the group which might have persuaded the ordinary person of the moral and economic benefits of free markets were the “intellectuals”, however as the 19th century wore on the intellectual class increasingly moved away from CL and adopted socialist, nationalist, or other statist beliefs instead. This movement away from CL was noted by writers such as Julian Benda, La Trahison des Clercs (The Treason of the Intellectuals or The Betrayal by the Intellectuals) (1927), Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942), and Friedrich A. Hayek, “The Intellectuals and Socialism” (1949). Why the CL movement “lost” the intellectual class to socialism and statism in the late 19th century is an important question which modern day CLs have to find an answer to and a way to reverse the situation. A common response is that the uncertainties of making a living in a free market where one’s work is only rewarded if consumers value your work enough to voluntarily pay for it, drove intellectuals into the apparently more certain and predictable arms of the state which provided them with secure jobs in the administration or the state funded academy. Another explanation is that intellectuals adopted the old aristocratic disdain for “productive labour” and did not want “to dirty their hands” with commerce. Why this was the case is unclear.

Of course, another response might be that CL is wrong both morally and economically speaking, that the “intellectual class” recognized this, and were therefore right to turn their backs on it.

[See Richard Ebeling, “Can Capitalism Survive? 80 Years After Schumpeter’s Answer” The Future of Freedom Foundation (Apr. 19, 2022) Online .]

6.) CLs lost their “Vision” of what a free society should be like: CLs lost their “vision” of what a fully free society might look like and why this was desirable, and thus “lost” the moral high ground to the socialists and statists. Their loss of vision made their ideology less attractive to the young, who found an alternate and more attractive and inspiring vision in socialism/Marxism, nationalism, and fascism. One of the reasons why radical liberals in the late 18th and early 19th century were able to put forward an inspiring vision of what emancipation might achieve, and thus attract many people to the CL cause, was their passionate sense of justice, or rather their hatred of the injustice which they could see all around them. This passion came out in their polemical writing, best exemplified by Thomas Paine whose “Common Sense” (1776) and “The Rights of Man” (1791) inspired CLs on both sides of the Atlantic. Who in the late 19th century was writing similar inspiring essays to attract a new general of young people to CL? Very few – perhaps only the aging members of the last generation of “old liberals” like Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) and Auberon Herbert (1838-1906).

This loss of “vision” was pointed out by Friedrich Hayek, James Buchanan, Murray Rothbard, and Robert Nozick in the second half of the 20th century, and again by Richard Ebeling and Peter Boettke in the 21st.

On CL Visions of the Future Free Society see:

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future I” (27 August, 2021) here

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future II: The Contribution of Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)” (29 Aug. 2021) here

- “Classical Liberal Visions of the Future III: Liberal Experiments, Frameworks, and Archipelagos” (11 Oct. 2021) here

- “Hayek on a Liberal Utopia” (11 Sept. 2021) here

What still needs to be done?

I will reserve discussion of this matter to a future post. In the meantime see my thoughts on the problems we face and some strategies to solve them:

- “Strategies to Achieve a Free Society” (24 March, 2022). Online and also here.