[Also see my post on “James Gillray on Debt and Taxes during the War against Napoleon (23 February, 2021).]

Last Monday (14 June) was “celebrated” here in Australia with a public holiday in most of the country. For some reason the eponymously named state of “Queensland” missed out. Perhaps they wanted to avoid the charade played by the rest of the country by “celebrating” her birthday on her real birthday (21 April 1926).

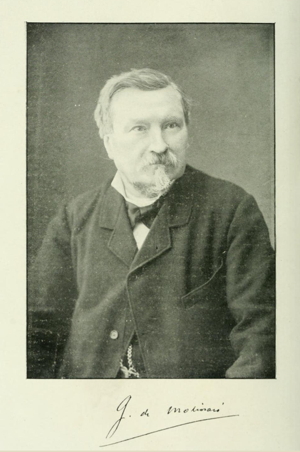

Not that it really matters for us republicans and libertarians as the “pomp and circumstance” of the modern monarchy (birthdays, royal weddings and births) merely hides the unpleasant truth about how monarchs got their power and authority in the first place (one of their ancestors was the dominant warlord of the day), and whether or not they acquired their vast property holdings and wealth in a legitimate fashion (through conquest and forcible seizure, subsidies from taxpayers) not by making voluntary exchanges of justly acquired or produced goods and services. [For a corrective, see the historical analyses of the origin of monarchies by Thomas Paine, Gustave de Molinari, and Franz Oppenheimer.] Instead they live off the interest and rent they receive from these holdings, along with a negotiated bequest or donation from the taxpayers (via Parliament) to cover the costs of their “official duties”. [Again, for a corrective see the work of the English radical Individualist John Wade who, in the Extraordinary Black Book (1832) collected the data concerning who got what from the British taxpayers as part of the “Civil List”.]

Furthermore, much of what we today associate with the “pomp and ceremony” and the “mystery” of divine or semi-divine rule, what has been called “royal tradition” is in fact a modern invention, perhaps started by the savvy Queen Victoria (1819-1901, reigned 1837-1901).

[See, The Invention of Tradition. Ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge University Press, 1983).] I have argued elsewhere that public ceremonies (whether monarchical or presidential) are a powerful means of instilling reference for and obedience to authority in the minds of the people. See the series of lectures I have given on “The Culture of Liberty vs. the Culture of Authority”; “Propaganda and Obedience to the State”, “Political Propaganda and the State: On Seeing through the Culture of Authority”.] And more recently, I have posted on the older work of Étienne de la Boétie on why people voluntarily submit to this form of “servitude” under a so-called constitutional monarchy, which is mostly of the mind, but which sometimes intrudes into “real politics” when the “crown” or his/her representatives start sacking governments (such as the dismissal of Gough Whitlam in 1975).

So it is a relief to sometimes go back into the past when monarchs were treated with much less fawning admiration and respect, such as the decades of the late 18th and early 19th centuries when the British political caricaturist James Gillray (1756-1815) was cutting lose with his witty and very sharp “cartoons” which showed the more grasping and repulsive behaviour of royals such as King George III and Queen Charlotte and their dissolute son George which would later become King George IV. One can only hope that our era might spawn its own Gillray to mock and expose the shenanigans of the current extended “royal family” which “rules” the U.K. along with its satellites and dependencies like the Commonwealth of Australia.

With this in mind, I have assembled a number of Gillray’s cartoons to serve as an example for contemporary cartoonists, as well as to help me temper my politically grumpy mood and assuage my troubled republican soul. These images are critical of several things which apply even today to the royal family:

- the sheer cost of supporting such an extended family and their hangers-on at taxpayer expense when ordinary people were suffering hardships and deprivation as a result of the economic impact of war (the wars against France in America in the 1740s, and then the American war of independence in the 1770s, and the war against the French Republic and then Napoleon in the 1790s)

- that behind the façade of upright and exemplary behaviour (supposedly as the head of the established Christian church) lay appalling personal behaviour which brought the state and the church into disrepute

- that royals could and should be represented as just like ordinary people and therefore not worthy of being regarded as any way superior or “chosen by God” to lead their subjects and act as “head of state”

How Royals want to be depicted in Official Portraits

[King George III (1738-1820) – reigned 1760-1820. Alan Ramsay’s depiction of George in his coronation robes.]

[Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte) (1744-1818) who was queen by marriage to King George III. Painting by Thomas Gainsboroguh 1781]

[King George IV (1762-1830) – reigned 1820-1830 (regent from 1811). He was the eldest child of George III and Charlotte.]

The Sordid Business of Royal Weddings and Births to continue the Line and Boost the Family Budget

The marriage of their sons to suitably wealthy European monarchs was a strategy used by George III and Charlotte to increase their wealth independently of the whims of Parliament. In “The Introduction” (22 November 1791) we see an ecstatic King and Queen literally leaping out of their thrones in anticipation of a huge dowry to be paid by the Prussian King for the marriage of his daughter Princess Frederica Charlotte to their son Prince Frederick, the Duke of York.

George cannot believe his eyes when he sees the bags of gold being offered and has to use his spy glass to make sure he has not made an error (this was a common trope by Gillray as George III’s eyesight was deteriorating). Charlotte stretches out her apron in order to receive the coins being carried by Frederica and a large mustachioed Prussian soldier who is escorting the young couple (the bags being carried by the soldier have the sum of £100,000 written on them). George and Charlotte are also happy because Frederick’s marriage was the first legitimate marriage of any of their sons and might produce an heir.

However, the reported amounts of the dowry were exaggerated but the newly wed Prince Frederick, the Duke of York, was granted an additional £18,000 a year from Parliament, and the George III contributed £12,000 a year out of the Civil List. This was in addition to the money he received from the established church in Ireland of £7,000 a year and the revenues generated by the Bishopric of Osnaburgh.

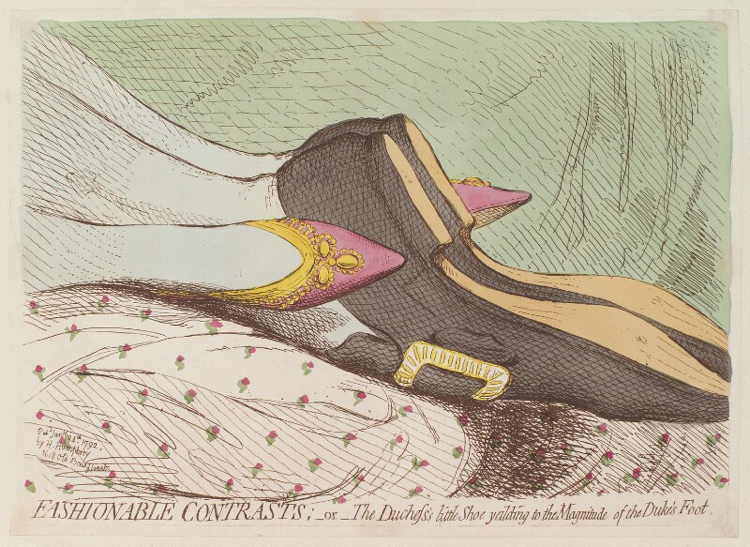

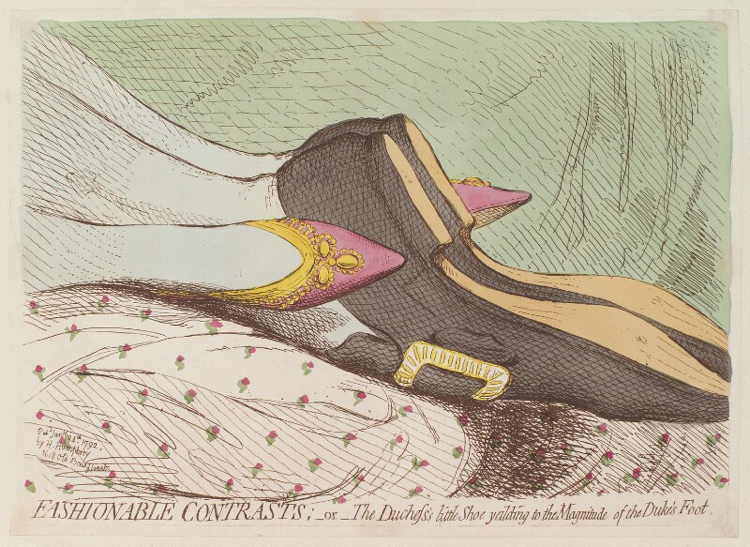

One could usually not accuse Gillray of being subtle, but on occasion he was, as this drawing “Fashionable Contrasts” (1792) demonstrates.

Five years before the birth of George’s (the Prince of Wales) daughter Charlotte, the marriage of his younger brother Frederick (the Duke of York) to Frederica Charlotte, the oldest daughter of the King of Prussia, became the subject of a media frenzy. Perhaps because she was very short, plain looking, and quite plump and thus without the hoped for “aristocratic bearing” one might want to see in a member of the royal family, the press fixated on the size of her feet, which were very small or “dainty” in polite speech. There was also the hope that this couple might produce a legitimate male heir to throne without the complications created by his older brother of an illegal marriage to a catholic or children conceived out of wedlock by one of his many mistresses.

Gillray’s contribution to this media frenzy was to depict two pairs of feet, one pair clearly male with buckles and quite large, lying atop another pair clearly female which were pink and bejeweled and very small. The full title of the drawing was “Fashionable contrasts; – or – the Duchess’s little shoe yielding to the magnitude of the Duke’s foot.”

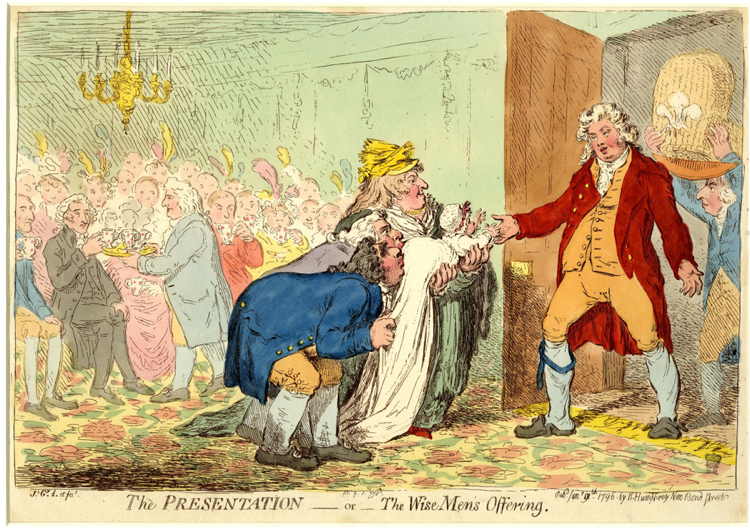

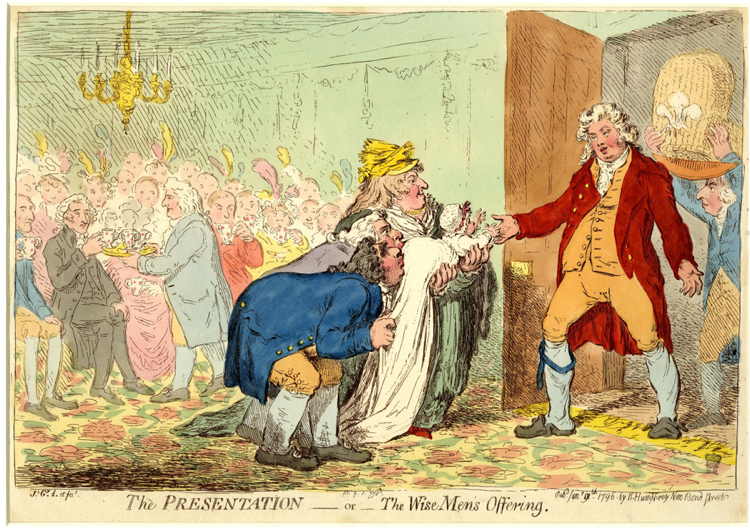

“The Presentation – or – the Wise Men’s Offering” (9 January 1796).

The son of George III, also a “George” (the future IV), was forced into a loveless marriage to his cousin Princess Caroline of Brunswick in order to get a dowry to pay off his considerable debts. They had one child (his only legitimate child and thus the presumptive heir to the throne), Charlotte, who was born on 7 Jan. 1976, before they separated and George went back to his mistresses.

Gillray has drawn a disheveled and presumably drunk George who has just arrived and is presented with his child (wrapped in swaddling cloth’s like Christ) by an old woman who may be the well-known prostitute and madame “Mother Windsor”. The gathering is of members of the Whig party who are trying to ingratiate themselves with the Prince. Two of their leaders, the two wise men of the party, Charles Fox and Richard Sheridan, are ostentatiously “ass kissing” the baby princess Charlotte. The message appears to be that everybody involved is “prostituting” themselves for something or other.

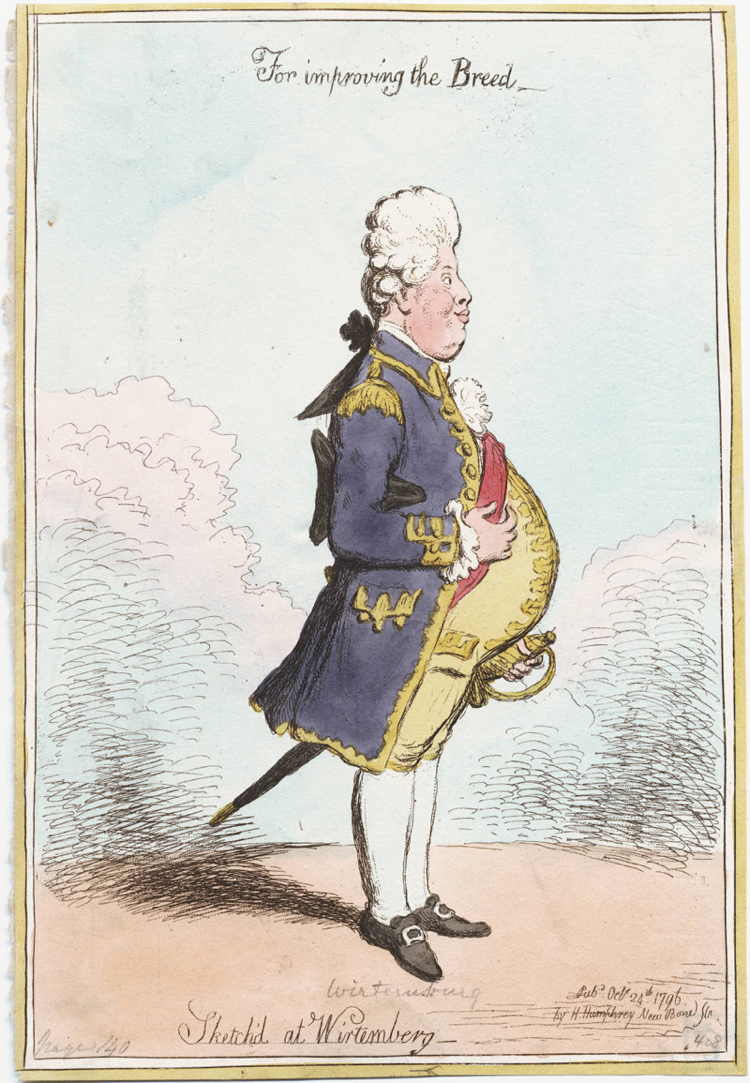

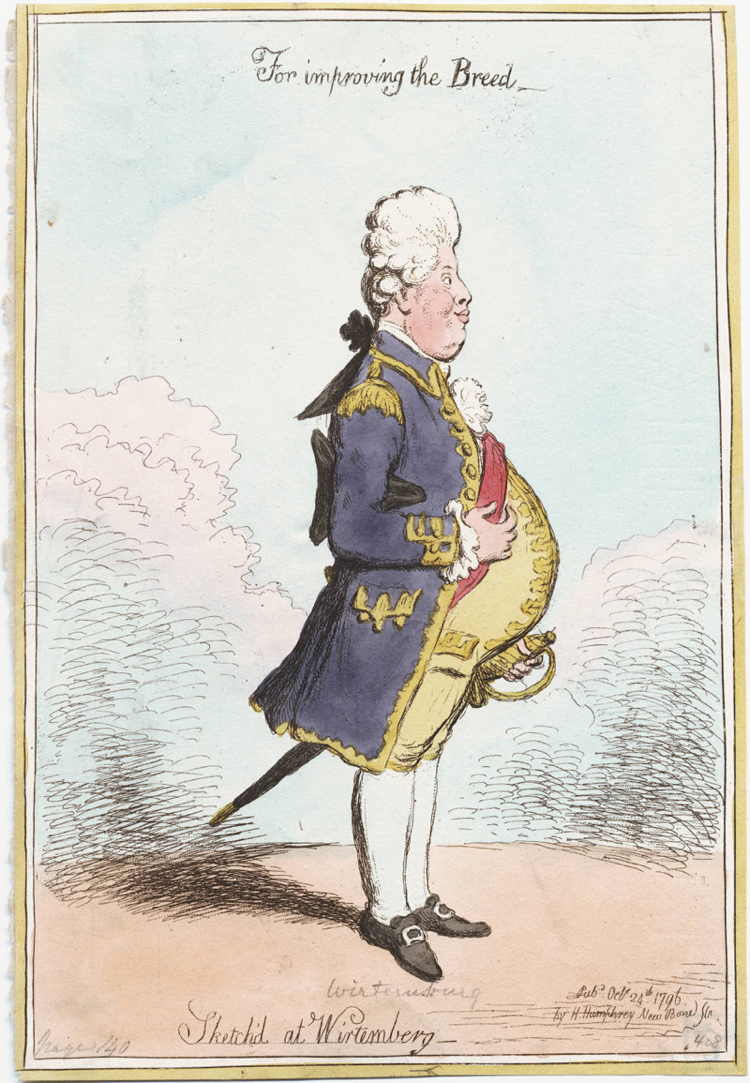

George III and Charlotte also had a daughter, Charlotte Augusta, or the Princess Royal, to marry off. After many years of negotiation for suitable terms, a marriage to the hereditary Prince Frederick of Wurtemberg was announced in 1796. Gillray immediately seized upon certain physical attributes of the Prince to satirize which appeared in the drawing “For Improving the Breed” (Oct. 24, 1796).

He was physically huge, being rather corpulent (as the size of his belly indicates), very tall for the period (some 6 feet 11 inches or 2.1 meters), and weighed 440 pounds or 200 kilos. For a family as sickly looking as George’s and Charlotte’s this German prince was seen by Gillray as a wonderful breeding opportunity to improve the English royal bloodline. One should also note the obviously phallic handle of the sword protruding just under his belly. The only thing missing is an image of his teeth to complete the picture.

In “The Bridal Night” (May 18, 1797) the extended royal family and their entourage are seen escorting, almost triumphally, the bridal couple into the bed chamber in Windsor Castle on their first night together.

I say “triumphal” as the picture on the wall behind the procession is of an elephant with a cupid sitting on its head blowing a trumpet with the title beneath “Le Triomphe de l’amour” (The Triumph of Love). The word “Love” may also be meant sarcastically as beneath the picture we can see Prime Minister Pitt with a sack of money labelled £80,000 which is the amount Parliament voted for her dowry (thus freeing George III and Charlotte from having to come up with the cash for the wedding to proceed). Thus the title should probably read “The Triumph of Money and Power”.

There is so much detail in the drawing that I will just quote the British Museum commentary on the image:

An elaborate design. The Prince of Würtemberg, grotesquely corpulent, conducts his bride in the procession (right to left) towards the bridal chamber which is led by the King and Queen. George III, plainly dressed and wearing a hat, partly concealed by a pillar, hurries forward; in each hand is a candle-stick holding a guttering candle-end (cf. BMSat 8117). The Queen, covered with jewels and her face hidden by a poke-bonnet, carries a steaming bowl of ‘Posset’. On the back of the Prince’s coat are slung five ribbons from which dangle the jewels of orders; three garters encircle his leg; a star decorates the bag of his wig. The Princess gazes at him from behind her fan. Round her waist is the ribbon of an order, to which is attached a jewel containing a whole length miniature of her husband, which exaggerates his corpulence.

Behind the Princess is a group of princes: the Prince of Wales, in regimentals, is fat and sulky. Prince William of Gloucester stands with splayed-out feet as in BMSat 8716. The Duke of Clarence (caricatured) puts a hand on the right arm of the Prince of Wales. Behind is the more handsome head of the Duke of York. These four heads are clever juxtapositions of variations on the family features. Behind them is the grotesque profile of the Stadholder with closed eyes. The sharp features of Lady Derby tower above the Stadholder. Next him is the Princess of Wales, not caricatured. Two princesses hold up their sister’s train, and, behind, a sea of feathered headdresses recedes in perspective under a lighted chandelier.

Salisbury (left), the Lord Chamberlain, standing stiffly in profile to the right, much caricatured, with wand and key as in BMSat 8649, holds open the door through which the King is about to pass. Pitt, on the outskirts of the procession, carries a sack inscribed ‘£80,000’ (the amount of the Princess’s dowry). On the wall is a large picture, inscribed ‘Le Triomphe de l’Amour’, of an elephant with a little cupid sitting on his neck blowing a trumpet.

It is not clear from the drawing how far into the royal bedchamber the procession is intending to go and how long they will stay. It is amusing to speculate.

Economising on Royal Expenditure: Faux and Real

After fighting and losing the war to prevent the independence of the American colonies the British were forced to capitulate and sign a peace agreement known as the Treaty of Paris in September 1783. This left the British state with massive debts to pay off which was done by levying taxes of all kinds on the ordinary working people of Britain. In this drawing, “A New Way to Pay the National Debt” (1786), Gillray shows how, while ordinary taxpayers were made to suffer, the elite and the Royal family profited from enormous grants authorized by Parliament.

The immediate political background to the drawing was the introduction by Prime Minister William Pitt of a bill in Parliament on 3 April 1786 to reduce the size of the debt, and the continuing refusal of George III to assume responsibility for the large personal debts run up by his son George, the Prince of Wales. Pitt submitted his bill before Parliament and debates began 5 and 6 April, 1786. One of the clauses of the bill concerned a supplementary grant to the “Civil List” (the annual payment to the Royal family and their entourage) of £210,000 to discharge their personal debts. By one estimate, the war against the American colonies had cost the government about £80 million which had increased the size of the national debt to about £250 million. To raise additional funds, the Pitt government imposed taxes a range of goods such as the following: wine, windows, spirits, tobacco, bricks and tiles, gold and silver plate, imported silk, men’s hats, women’s ribbons, perfume, hair powder, horse and carriages, and sporting licenses.

The drawing shows the arched entrance of the Royal Treasury outside of which are gathered in a semi-circle around King George and Charlotte a group of uniformed men playing their instruments and who have their pockets overflowing with coins. They represent the “placemen” who have received sinecures from the Crown and are now “playing George’s tune”. George III and Charlotte stand before a wheel barrow filled with sacks of money and their pockets are literally bulging with coins. George is holding a sack of money on which is written £100,000. Charlotte is also seen taking snuff out of a gold box. The Prime Minister William Pitt, also with pockets bulging with cash, is handing George III yet another large sack of money. On the wall behind them are wall posters and flyers with revealing slogans and titles on them. The central group is framed by a poor armless and legless beggar (possibly a disabled naval veteran) sitting on the ground to the left with his begging hat sitting empty between his legs; and to the right is the figure of George, the Prince of Wales, disheveled and wearing torn clothing receiving a supplementary bag of money with a note which reads “Accept £200000 from your Friend Orleans”, from a well-dressed Frenchman who perhaps is a representative of the French aristocrat, the Duc d’Orléans).

Although depicted as disheveled and impoverished, George the Prince of Wales had received and continued to receive substantial amounts of money from Parliament to fund his decadent lifestyle. When he turned 21 in 1783 he was granted a one off payment of £60,000 from Parliament and an annual income of £50,000. This generous amount was insufficient to cover his gambling and racing debts, and the expensive renovations to his home. To cover these additional expenses Parliament granted him a further £24,000 in 1787 to cover them.

Below the drawing are some amusing dedications, such as “Designed by Helagabalis” (a profligate Roman emperor), “Dedicated to Mons. Necker” (the French Minister of Finance who tried, and failed, to reorganize the French taxation system before the French Revolution), and “Executed by Sejanus” (the head of the Praetorian Guard under emperor Tiberius).

Concerning the posters on the rear wall, one commentator has deciphered them as:

To the left of the arch, for instance, is a notice headed with a violin and bow, announcing the arrival of large assortment of musicians from Germany for the royal entertainment. (Music was one of George’s passions.) This is juxtaposed to another notice containing “Last Dying Speech of Fifty-Four Malefactors executed for robbing a Hen-Roost,” suggestive of the plight of a desperate and starving British populace. The juxtaposition of the two may be intended to recall the cruel emperor Nero who, in the popular phrase, “fiddled while Rome burned.” A third notice suggests that charity from such a king is “a Romance,” an implausible fiction.

To the right of the arch, the handbills lament the spending of the King and Court with “Oeconomy, an old Song,” and suggest the feelings of the British electorate, imposed upon by Pitt’s succession of taxes with: “British Property a Farce,” and “Just published for the benefit of Posterity: The Dying Groans of Liberty.”

The British Museum entry for this drawing notes further that:

On the Treasury wall is a number of placards and torn shreds of paper: ‘Charity A Romance’ (torn); ‘God save the King’ (torn); ‘Last Dying Speech of Fifty-Four Malefactors executed for robbing a Hen-Roost’, headed by a number of bodies hanging from a gibbet (an allusion to the king’s farming activities at Windsor, see BMSat 6918, &c.); a bill headed by a violin and bow and inscribed ‘From Germany just arrived a large & Royal Asortment’ (on the king’s fondness for German musicians); ‘Œconomy an old Song’ (torn); ‘British Property a Farce’ (torn); ‘Just publish’d for the Benefit of Posterity: The Dying Groans of Liberty’; a placard with the Prince of Wales’s feathers and the motto ‘Ich Starve’ (torn), in place of ‘Ich dien’, and another with two clasped hands and the word ‘Orleans’ (torn). The last two are above the heads of the Prince and the Duc d’Orléans.

In the drawing “Frying Sprats, Toasting Muffins” (28 November 1791) Gillray mocks the supposed parsimoniousness of the King and Queen who, despite their vast wealth, cook meals for themselves (sprats or small fish, and muffins which were regarded as food which the poor would eat) over an open fire in order to save money. This is belied by the bulging sack of coins tied to the Queen’s waist. Their claim to be poor was a ploy to justify not spending their wealth on improving the lot of the poor of England or paying off their son’s very large debts, which they expected the Parliament to cover in a grant.

Another drawing mocking the frugality of the King and Queen was “Temperance enjoying a Frugal Meal” (28 July 1792) where George eats a couple of boiled eggs and the Queen a simple green salad.

Other indications of their frugality is the pitcher of water (not wine) standing beside the table, an empty picture frame on the wall showing that they do not spend money on frivolous artistic decorations, and the fact that the King’s britches have been mended with a patch.

The Physical and Moral Deficiencies of the Royals

One of the great myths of monarchy was, and still is to some degree, that those who were destined to rule over us are somehow physically, morally, and spiritually superior to us normal, mortal creatures, that they were somehow chosen by god, by destiny, or by history to assume this important role. But, given the behaviour of the royals in the 1790s and 1810, it was not difficult for Gillray to demonstrate the exact opposite, that they were gluttons, had serial mistresses, fathered children out of wedlock, amassed huge gambling and other debts, and had various physical disabilities, the least of which was being feeble sighted and the worst being feeble minded or even insane in the case of George III (after 1811).

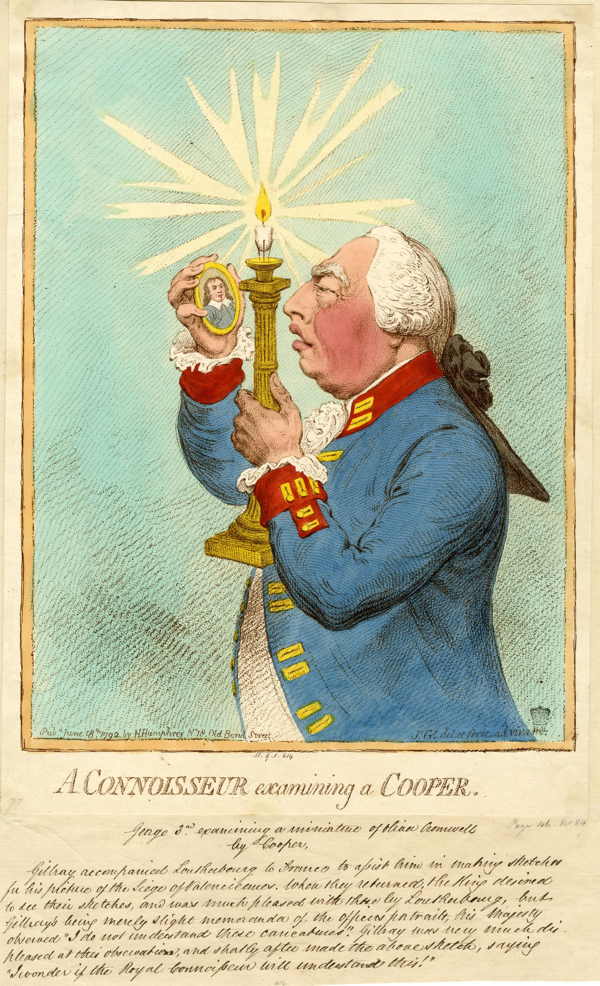

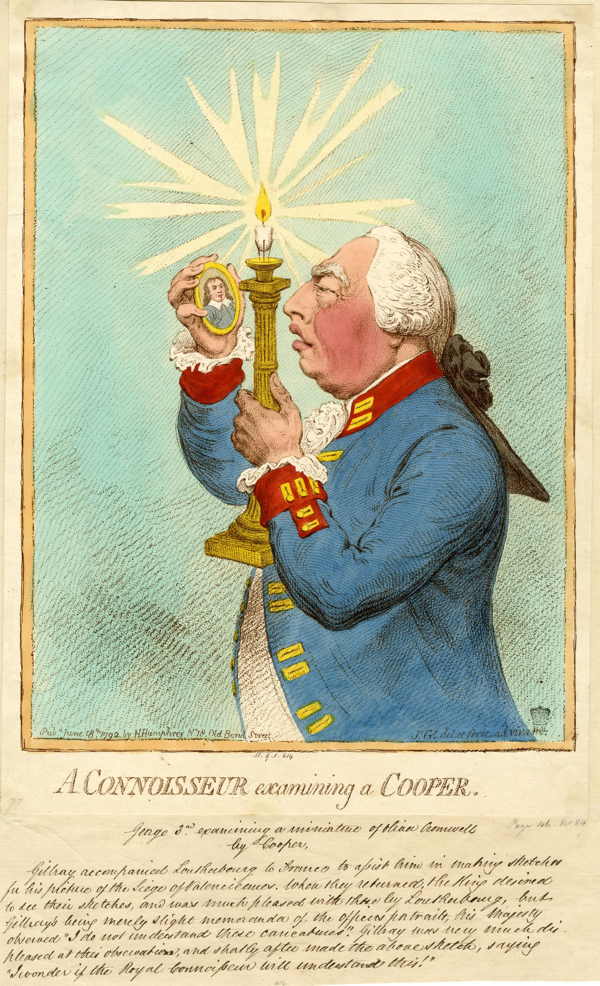

George III was a gift to caricaturists given his many physical weaknesses and obsessive behavior. For starters, he was obsessed with saving money (parsimoniousness) on trivial matters (symbolized by him re-using half finished wax candles) when the regime was in dire financial straits because of the massive cost of the wars waged during his reign. His health deteriorated, his eyesight began to fail, he suffered from dementia, and ultimately was declared unfit to rule, thus ushering in a period of regency after 1811 when his dissolute son, the future George IV ruled in his place. So it was an open invitation for caricaturists to link his physical weaknesses and failures to his political ones.

In the following two drawings Gillray links George III’s physical nearsightedness to his inability to see the two kinds of threat to his regime. One from the Republican or Cromwellian threat from within; and the second from Napoleon from without.

In “A Connoisseur Examining A Cooper” (18 June 1792) we see depicted George III squinting, even under the bright light of his stub of a candle (used to save money), to see the details of a small picture of Oliver Cromwell, who had ruled England as “Protector” between 1653 and 1658 following the overthrow and execution of Charles I in 1649. The picture of Cromwell had been painted by Samuel Cooper and George is supposed to be a connoisseur of fine art, hence the title of the drawing. The North American colonies had of course seceded from the British Crown in 1776 and the French had deposed King Louis XVI in September 1792 and executed him in January 1793. Many in England thought George might be next, including Gillray perhaps, as his very speculative though detailed drawing of a meeting of post-revolutionary British politicians planning the next step in “L’Assemblée Nationale, or Grand Co-operative Meeting in St. Ann’s Hill” (18 June 1804) seems to show (see below).

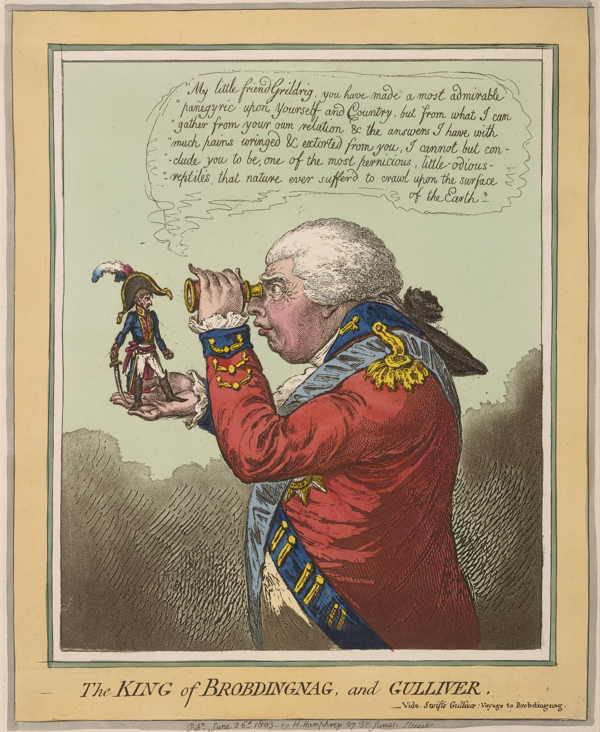

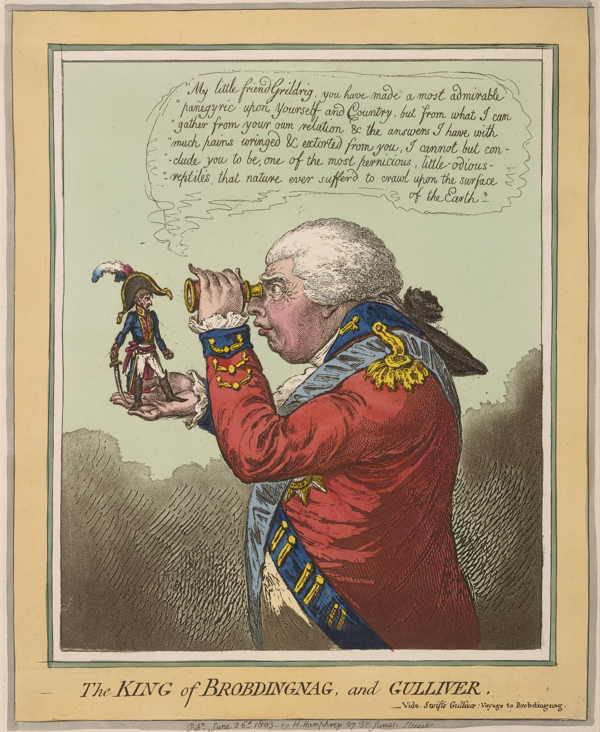

In the quite similar “The King of Brobdingnag and Gulliver” (26 June 1803) we have George III dressed in a military uniform examining through a spy glass a miniature Napoleon whom he is holding in the palm of his hand.

Gillray depicts Napoleon as Gulliver (from Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels (1726)) and George as the King of the fictional land of giants named Brobdingnag. The speech bubble is a quote from the novel where the King replies to Gulliver’s description of what English society and government was like:

My little friend Grildrig, you have made a most admirable panegyric upon Yourself and Country, but from what I can gather from your own relation & the answers I have with much pains wringed & extorted from you, I cannot but conclude you to be one of the most pernicious, little – odious -reptiles, that nature ever suffer’d to crawl upon the surface of the Earth.

The joke of course might be that Gillray has reversed matters and that King George is the “Lilliputian” and Napoleon the giant. Napoleon would not be cut down to size until a few years after this drawing was done in 1803, when his invasion of Spain (1808) began to fail and then his disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812 led to the complete route of his massive army.

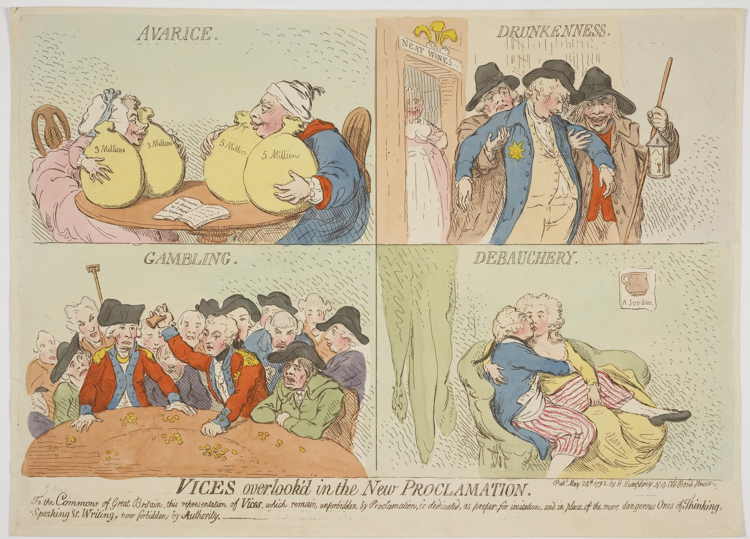

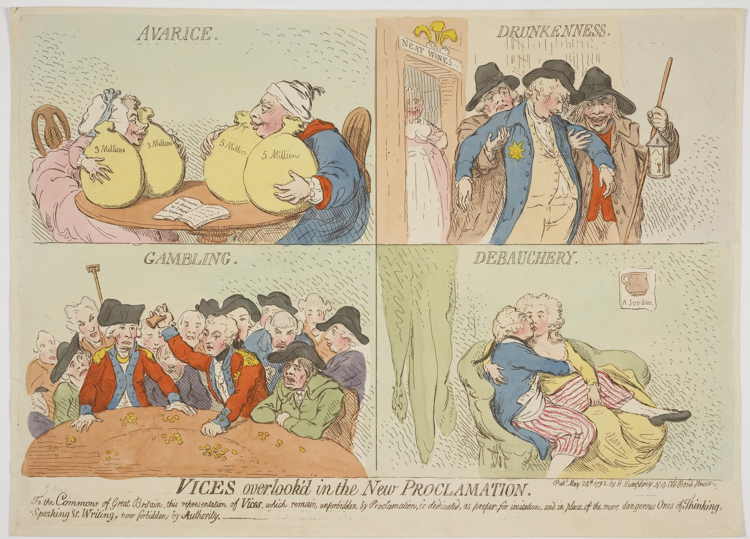

The moral deficiencies of the royal family were numerous and often the subject of Gillray’s barbs. One particularly damning drawing focused on four of the royals’ ”deadly sins” or vices, namely avarice, drunkenness, gambling, and debauchery – “Vices Overlook’d in the New Proclamation” (1792).

The drawing was a direct response to George III’s crackdown on the dissemination of revolutionary republican tracts like Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man which appeared on the streets of London in March 1791 and February 1792. The King issued a “Royal Proclamation Against Seditious Writings and Publications” in which he made a personal appeal to the people of England , his “faithful and loving subjects”, to resist such seditious material and to the magistrates to hunt down the authors, printers and distributors of such “wicked and seditious writings.”

Gillray used this drawing to point out the hypocrisy of the King acting against the “vice” of sedition while ignoring the vices committed by him, his wife, and his three sons, which he made explicit in the statement at the bottom:

To the Commons of Great Britain, this representation of Vices, which remain unforbidden by Proclamation, is dedicated, as proper for imitation, and in place of the more dangerous ones of Thinking, Speaking & Writing, now forbidden by Authority.

In the first panel is shown the vice of “avarice” in which the King and Queen are hugging large sacks of money while seated at a table in their pyjamas. The queen has two sacks each marked as containing three million pounds, while the King has two five million pound sacks. Open on the table is an account book on which is written “Account of Money at interest in Germany”, a reference to the rumor that the Queen kept secret accounts in banks in her native German state of Mecklenburg.

The second panel, called “drunkenness” shows a very drunk George (their eldest son, the Prince of Wales) being escorted out of a tavern cum brothel which serves strong “Neat Wines” (i.e. not watered down) by two burly looking nightwatchmen. The third panel shows another son Frederick, the Duke of York, standing at a gambling table surrounded by other gamblers getting further into debt. The fourth panel, called “debauchery”, shows Prince William Henry, the Duke of Clarence, wearing a naval officer’s jacket and striped pants, on a divan with his mistress Mrs. Jordan, whose name also appears as the title of picture on the wall, “A Jordan”, of a chamber pot.

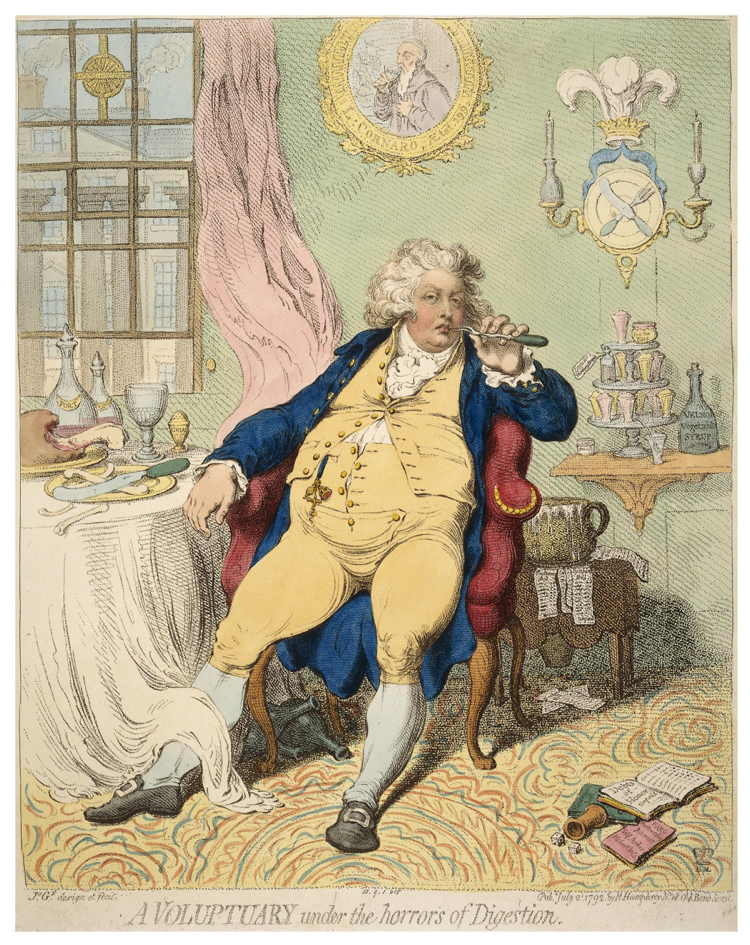

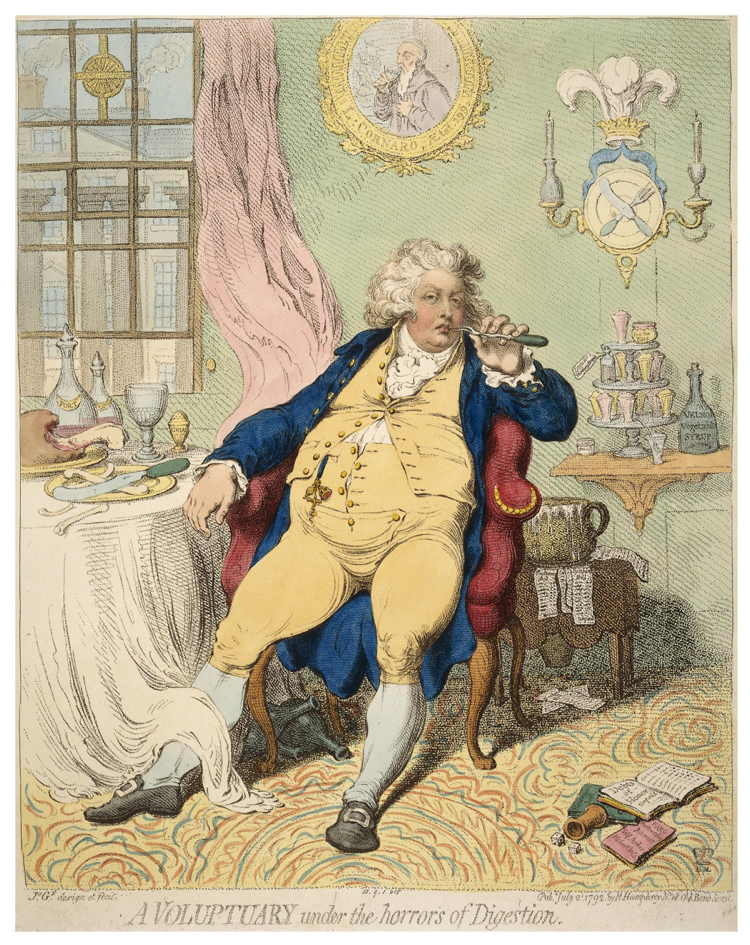

Gillray thought that the excesses of George, the Prince of Wales (or Whales as he was sometimes derisively called) deserved a drawing of its own. In “A Voluptuary under the Horrors of Digestion” (2 July 1792) we have a picture in which large circles predominate, thus emphasizing the circumference of his bloated belly in the middle of the picture.

George is reclining on a chair at his dining table having finished his meal. He picks his teeth with a fork, which is also part of his coat of arms hanging on the wall behind him – a crossed knife and fork surrounded by a wine bottle and wine glass each holding a candle. Beneath that is a multi-level cake server with all the medicines his diet and lifestyle requires – remedies for venereal disease, piles, and bad breath. Beneath that in turn is a chamber pot overflowing with his excrement which acts as a paper weight for all his unpaid bills.

On the floor are dice and some books about horse racing and gambling. Through the window at the top left of the picture is the outline of the unfinished and hugely expensive renovations he demanded for his home.

The Dangers faced by Royals when Living in a Revolutionary and Republican Age

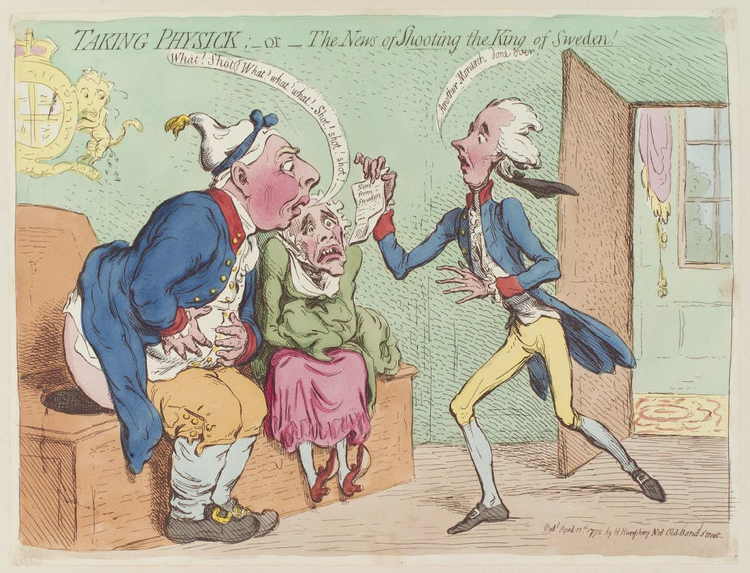

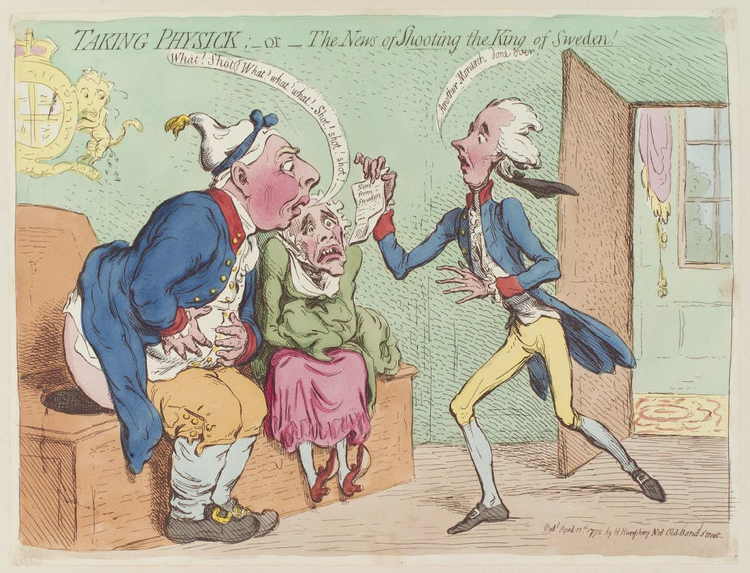

“Taking physick – or – the news of shooting the King of Sweden!” (1792).

George III and Charlotte are brought the news that yet another monarch has been killed (“done over”) by revolutionaries – this time the King of Sweden. They are both sitting in the lavatory literally shitting themselves in fear.

If a political assassination did not remove George III then another possibility was an uprising to install a constitutional monarchy. Gillray satirically imagined such a possibility in the very detailed and quite complex drawing of a meeting of an English equivalent of the French National Assembly of 1789: “L’Assemblée Nationale, or Grand Cooperative Meeting in St. Ann’s Hill” (18 June 1804).

Among the throng of people who were supposed to be the leaders and supporters of a new English Republic we can see in the centre Charles Fox and his wife. They are hosting a reception attended by the two major parties of the Opposition, the supporters of Fox and the supporters of Grenville, who might form a “coalition” or “co-operation” to run the republic. There is also a suggestion that with George III out of the way, his son might be persuaded to join the group as a figure-head. The half-figure on the right, dressed in a blue jacket is George (the Prince of Wales). He might be bought off to support the coup if they agreed to pay off his considerable gambling debts. For a more detailed description and attempt to identify all the figures present see the commentary at the British Museum website.

For those who like trivia, some of the incidental detail in the drawing is quite interesting. For example, the Prince of Wales has a paper in his back pocket on which is a quote from Shakespeare’s play Henry IV Part I, where Prince Hal says how he will appear to go along with their “unyoked humour” until such time as he decides to throw off “this loose behaviour” and redeem himself:

I know you all, and will awhile uphold

The unyoked humour of your idleness.

Yet herein will I imitate the sun,

Who doth permit the base contagious clouds

To smother up his beauty from the world,

That, when he please again to be himself,

Being wanted, he may be more wondered at

By breaking through the foul and ugly mists

Of vapors that did seem to strangle him.

If all the year were playing holidays,

To sport would be as tedious as to work;

But when they seldom come, they wished-for come,

And nothing pleaseth but rare accidents.

So when this loose behavior I throw off

And pay the debt I never promised,

By how much better than my word I am,

By so much shall I falsify men’s hopes;

And, like bright metal on a sullen ground,

My reformation, glittering o’er my fault,

Shall show more goodly and attract more eyes

Than that which hath no foil to set it off.

I’ll so offend to make offence a skill,

Redeeming time when men think least I will.

And adorning the back wall of the room are some interesting pictures described at the British Museum page as follows:

The room is palatial. The centre decoration of the wall is an elaborately carved candelabra on a bracket: Napoleon, crowned, naked, and grotesquely emaciated, supports on his shoulders a terrestrial globe, straddling across his large inverted Republican cocked hat (see BMSat 10247, &c.). He looks intently down at Fox. On the left. and in shadow is an oval bust portrait of George III, ‘Pater Patriae’. The frame is decorated with palm-branches. On the r., in a tropical landscape, Indians kneel or prostrate themselves with gestures of adoration before an enormous rising sun. They are ‘Worshipers of the Rising Sun’. The ornate frame is garlanded with grapes and surmounted by the Prince of Wales’s coronet and feathers.

The “Big Picture” of Kings, Politicians, and Emperors carving up the world for their own benefit

By 1805 when these two drawings were made Gillray had come to realize that the behaviour of kings and emperors, and politicians were very similar whether they were dealing with internal matters or foreign affairs. They behaved like “epicurean” diners who were willing to carve up the world for their own or their party’s (and supporters) benefit.

In “The Honors of the Sitting!! a Cabinet Picture” (January 30, 1805) we see George III sitting down to tea with the Tory politician Henry Addington who had been Prime Minister between 1801 and 1804. Peering anxiously through the window is Willam Pitt who had been PM between 1783-1801 and then again after Addington between 1804-1806. George is clearly playing one politician off against the other for his own benefit. At the table he shows Addington a multi-level serving platter with examples of all the kinds of “political goodies” he has to offer if Addington would come over to his side.

Addington had been made a Viscount and was now known as Viscount Sidmouth, which could be twisted to mean “Side-Mouth” or even “Side Board”. The commentary on the British Museum page) for this drawing describes the offerings as follows:

On the table stands a four-tiered dumb waiter. On the top-most shelf is a ducal coronet below are earl’s coronets, a star, and a ribbon; below again are (?) patents’ and on the lowest and largest shelf are loaves and fishes. Sidmouth sits grasping a knife and fork; on his plate is a fish, beside it a ‘loaf’ and a bottle of ‘Imperial Tokay’, the bottle stoppered with a crown. The King says: “Help yourself Doctor [cf. BMSat 9849] there is every thing you can wish for on the Side Board”. Addington answers, glancing sideways towards it, “They are indeed very inviting I cannot help turning a Side-mouth to them.” Pitt, outside a window immediately behind him (r.), looks into the room registering angry alarm; he says, “Zounds that Fellow will get all the Pickings.”

When transferred to the international sphere the political game of “the victor taking the spoils” is much the same in principle only with larger stakes. In “The plumb-pudding in danger: -or- State Epicures taking un Petit Souper” (1805) Pitt is back in office as Prime Minister and is show having dinner with Emperor Napoleon carving up a large plum pudding shaped like the earth.

Since Britain was the great naval power, Pitt has a fork shaped like a trident and is shown carving up the Atlantic Ocean to the west of Britain and including the West Indies. Napoleon, being the leader of a great land army uses a sword to cut off a large section of Europe including France Holland, Spain, Switzerland, Italy, and the Mediterranean, but leaving Sweden and Russia behind. Below the title at the top there is a quote from Shakespeare’s The Tempest iv. 1. : “the great Globe itself, and all which it inherit” with the further comment that it “ is too small to satisfy such insatiable appetites.”

In Act IV, sc. 1 of The Tempest Prospero finally gives his blessing to the marriage of Miranda and Ferdinand and then angrily and somewhat sadly reflects upon “this insubstantial pageant” which so preoccupied rulers to build and rule over “cloud-capp’d towers, gorgeous palaces, solemn temples, (and) the great globe itself”:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep. Sir, I am vex’d;

Bear with my weakness; my, brain is troubled:

Be not disturb’d with my infirmity:

If you be pleased, retire into my cell

And there repose: a turn or two I’ll walk,

To still my beating mind.