Talk given to a Conference on “A Brief History of Economic Thought,”

Institute for Liberal Studies, The University of Toronto, Bahen Centre

Friday 29 September, 2012

Online here

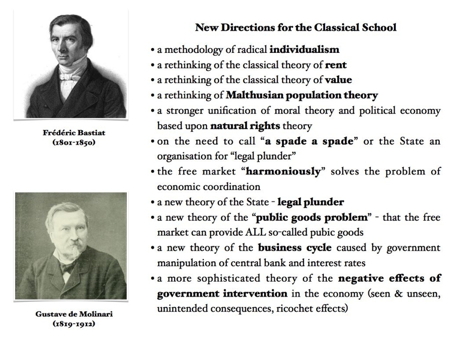

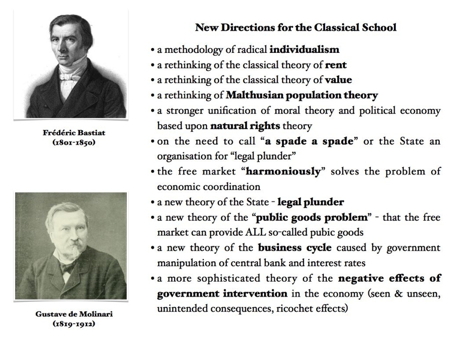

Abstract: The decade or so 1845-1856 saw a major re-thinking taking place in the nature of classical economic thought in France. The first generation of 19th century French political economy had built upon the legacy left by the Physiocrats of the 18thC (Quesnay, Turgot, et al.), and was comprised of Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), Charles Comte (1782-1837), Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862). They were active in the period between the appearance of Say’s Treatise in 1803 and the appearance of Dunoyer’s magnum opus De la Liberté du travail which appeared in 1845. A new second generation of French political economists emerged in the early 1840s under the umbrella provided by the Guillaumin publishing firm and the founding of the Political Economy Society and the Journal des Économistes in 1841-42. This younger generation was made up by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850), Charles Coquelin (1802-1852), Jean-Gustave Courcelle-Seneuil (1813-1892), and Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912). They made important contributions in the ten years between 1846-1856 which transformed the way economics was thought and done. Some of their innovations included the following: the appearance of a more radical radical libertarianism view of political economy in the areas of free banking (Coquelin), and the theory of plunder, subjective value theory, free trade and peace (Bastiat). They also began to challenge some of the key principles of the orthodox classical school of Ricardo, Malthus, and Smith, with new ideas about rent, value theory, and Malthusianism (Bastiat) and the private provision of public goods ( Molinari), and also free competitive banking (Coquelin). Some of these new directions in French political economy are discussed, with an emphasis on the work of Bastiat.