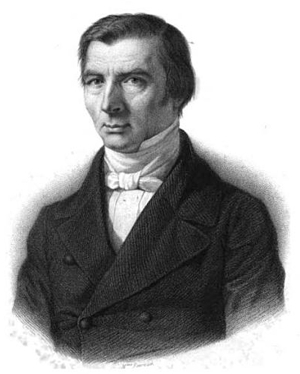

[Paris being encircled by the State: “The Fortifications of Paris and its Environs as adopted by the Chambers” (1841) . The pink area is the old part of the city which is surrounded by a customs wall with entry gates which was build in the 1780s to help the Farmers General collect taxes. The orange area is enclosed by a new wall of fortifications which surrounded the city and was build between 1841-44 and had a circumference of 33 km. The outer ring of red and green shapes are a series of 14 stand-alone forts and barracks which also surrounded the city.]

Molinari: “Liberty! That was the cry of the captives of Egypt, the

slaves of Spartacus, the peasants of the Middle Ages, and more

recently of the bourgeoisie oppressed by the nobility and religious

corporations, of the workers oppressed by masters and guilds. Liberty!

That was the cry of all those who found their property confiscated by

monopoly and privilege. Liberty! That was the burning aspiration of

all those whose natural rights had been forcibly repressed.” (S12)

This is a paper I will be giving at the Austrian Economics Research Conference (31 March to 2 April 2016) at the Mises Institute. The full title is “The Struggle against Protectionism, Socialism, and the Bureaucratic State: The Economic Thought of Gustave de Molinari, 1845-1855”.

It is actually a synopsis of a book-length work I have written which can be found here:

- HTML http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/EconomicThought/index.html

- PDF http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/EconomicThought/DMH_EconomicThoughtMolinari1845-55_28Mar2016.pdf.

It comes with two translations of essays by Molinari (in the Appendix), which are also available separately:

- “The Production of Security” article PDF http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/Molinari_ProductionSecurity.pdf

- “The 11th Soirée” chapter PDF http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Papers/Molinari/Molinari_Soiree11.pdf

Here is the abstract of the paper:

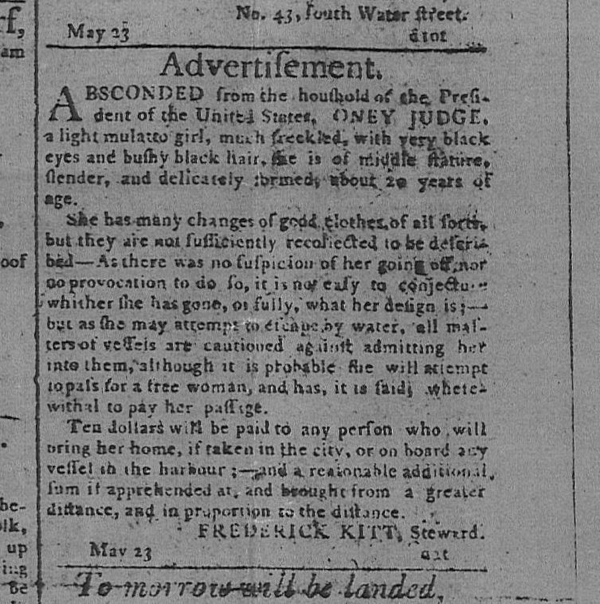

In the late-1840s in Paris there was an extraordinary group of economists who had gathered around the Guillaumin publishing firm to explore and promote free market ideas. One of these was the young Belgian economic journalist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) who was just starting out on his career which would lead him to eventually becoming one of the most important and prolific free market economists in Europe in the 19th century. In this paper I explore the first ten years of Molinari’s career as an economic journalist, author of a book on labor issues and slavery, and on the history of tariffs, a free trade activist, editor of classics of 18th century economic thought, lecturer on economics at the Athénée royal, activist in the 1848 Revolution, prolific author of articles in the Journal des Économistes, author of Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (Conversations on Saint Lazarus Street), contributor to the Dictionnaire de l’Économie politique, and, after going into self-imposed exile to Brussels after the coup d’état of Louis Napoleon in December 1851, professor of economics at the Musée royal de l’industrie belge, author of a treatise on economics, owner-editor of a newsletter L’Économiste belge, author of a book on the class analysis of Bonapartist despotism, and another popular book of “conversations” about free trade.

In the middle of this very hectic period of his life Molinari published a book for Guillaumin as part of their anti-socialist campaign after the February 1848 Revolution saw socialists seize power and attempt to implement some of their ideas, especially that of the “right to a job,” paid for at taxpayer expense, as part of the National Workshops program run by Louis Blanc. Within the new Constituent Assembly politicians like Frédéric Bastiat fought to terminate the National Workshops program and keep the “right to a job” clause out of the new constitution. Outside the Assembly the economists wrote scores of books and pamphlets to intellectually defeat socialist ideas at both the popular and the academic level. Molinari’s book was designed to appeal to educated readers and consisted of a collection of 12 “evenings” or “soirées” at which “a Conservative,” “a Socialist,” and “an Economist” debated important political and economic issues. In these conversations, the economist (Molinari) exposes the folly of both the conservative (who supported tariffs, subsidies, and limited voting rights) and the socialist (who supported government regulation of the economy, the right to a job for all workers, and the end to the “injustice” of profit, interest, and rent).

Molinari begins by arguing that society is governed by natural, immutable and absolute laws which cannot be ignored either by conservatives or socialists, and that the foundation for a peaceful and prosperous society is the right to private property. He then proceeds to explain the free market position on a host of topics to his skeptical audience. Some of the more controversial topics Molinari discusses include the following: intellectual property, eminent domain laws, public goods such as roads, rivers, and canals, inheritance laws, the ban on forming trade unions, free trade, the state monopoly of money, the post office, state subsidies to theaters and libraries, subsidies to religious groups, public education, free banking, government regulated industries, marriage and population growth, the private provision of police and defense, and the nature of rent. On all these issues, Molinari shows himself to be a radical supporter of laissez-faire economic policies.

For modern Austrian economists, what is most interesting about Molinari’s work from this period are the following:

- he believed that once freed from government regulations entrepreneurs would spring up in every industry to supply goods and services to customers

- he offers private and voluntary solutions to the problem of the provision of all so-called “public goods”, from the water supply to police services

- he seems to have inspired Rothbard to come up with his own theory of “anarcho-capitalism” in the 1950s and 1960s when he was writing MES and P&M

For modern libertarians, his book may well be the first ever one volume overview of the classical liberal position – much like an 1849 version of Rothbard’s own For a New Liberty (1973).