[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

The Multi-Dimensional Nature of Liberty

The full richness and complexity of the nature of Liberty is not well appreciated by most observers, especially mainstream media journalists and political scientists.

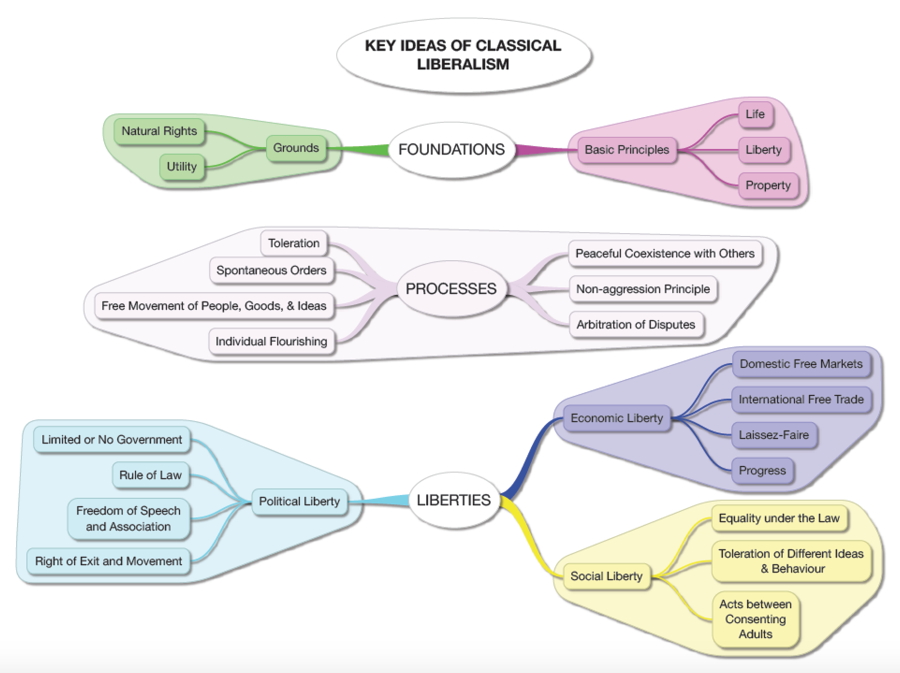

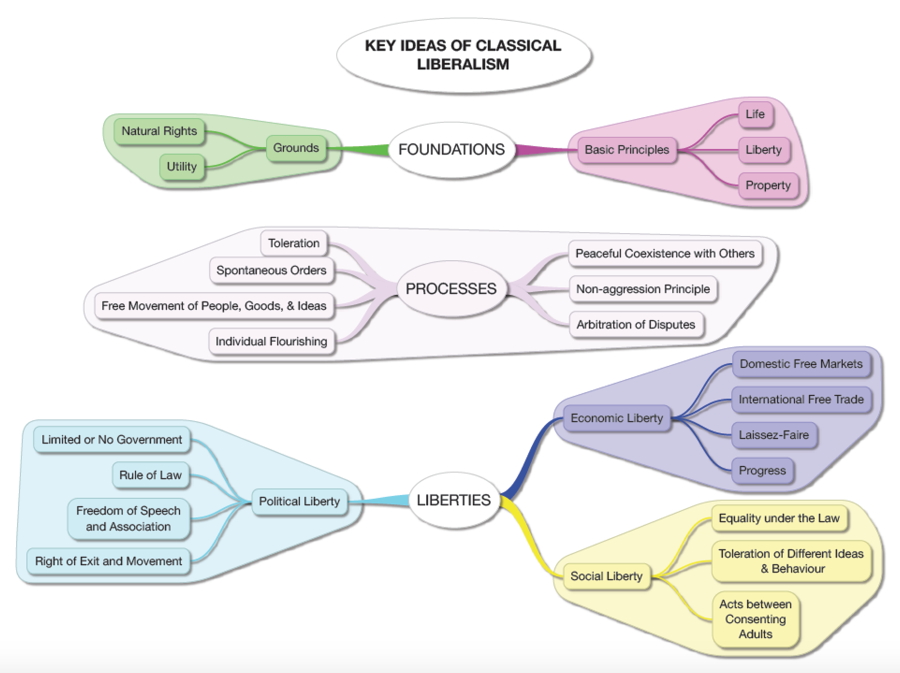

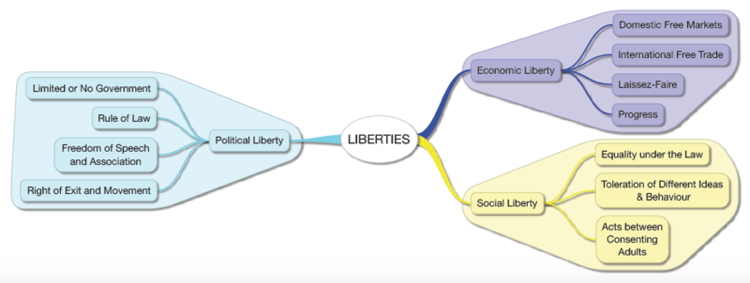

In other posts I have explored the relationship between the main components of a CL or Libertarian theory of Liberty which I will not repeat in detail here, only to assert that it is “multi-dimensional” in nature, consisting of at least three, and possibly four different threads or streams:

- political liberty

- economic liberty

- individual/personal/social liberty

- and sometimes legal liberty (if I don’t want to conflate this with the category of “political” liberty)

(See these posts for more information.)

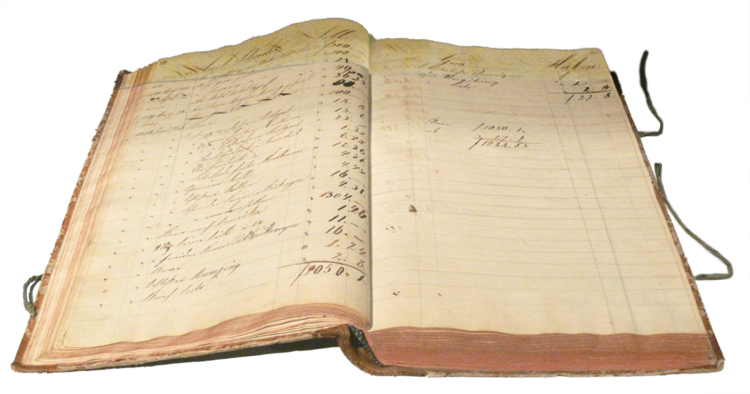

In this post on “The Key Ideas of Classical Liberalism: Foundations, Processes, Liberties” I discuss the meaning of this “concept map” of CL which I created:

Note: I have an updated version of these mind maps from April 2022 which is not yet online.

One can do the same for other political ideologies, determining what their position is on what they consider to be the proper power of the state, how much this power should be used to intervene in the affairs of the ordinary person, and how this might impinge upon the three kinds of liberty outlined above. This comparison can be done “qualitatively” (or “relatively”) by means of a “spectrum” (in one dimension) or a “political compass” or “matrix” (in 2 dimensions) which shows visually whether a society is more or less free in very general terms; or it can be done “qualitatively” by giving a score (say out of 10 or 100) for each of these liberties (perhaps in 2 or 3 dimensions) and then ranking the different regimes according to how much or how little freedom their citizens are able to exercise as measured by these scores.

I will discuss here some of the attempts to measure how much freedom a society “enjoys” (or “allows” its citizens to enjoy) and how successful I think these measurements are. Most are “qualitative” or “relative” in nature, such as

- the traditional Left-Right political spectrum with its 1 dimension

- my own “new political spectrum” between Liberty and Power (also 1 dimensional)

- David Nolan’s “Libertarian Spectrum” (1969) in 2 dimensions – Left (“liberal”) vs. Right (conservative) and Libertarian vs. Authoritarian

- a “simplified” Nolan chart in two dimensions and four quadrants – “Social” freedom and “economic” freedom

- the “Political Compass” which also uses “quadrants” and 2 dimensions, this time “Left” vs. “Right” and “Authoritarian” vs. “Libertarian.”

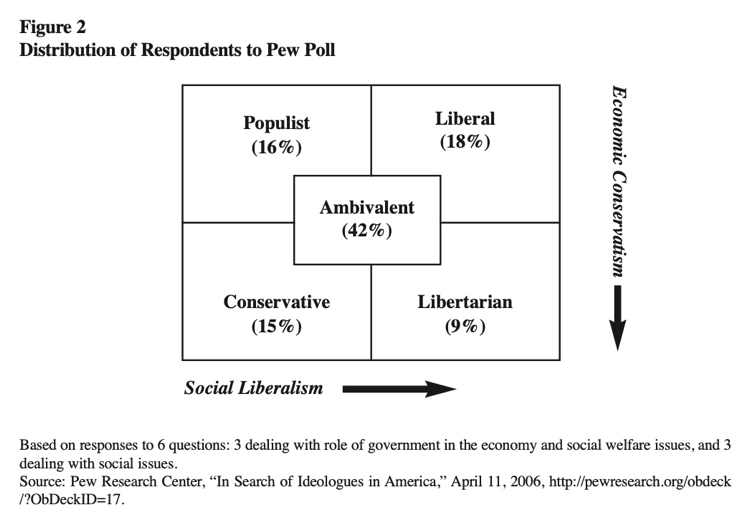

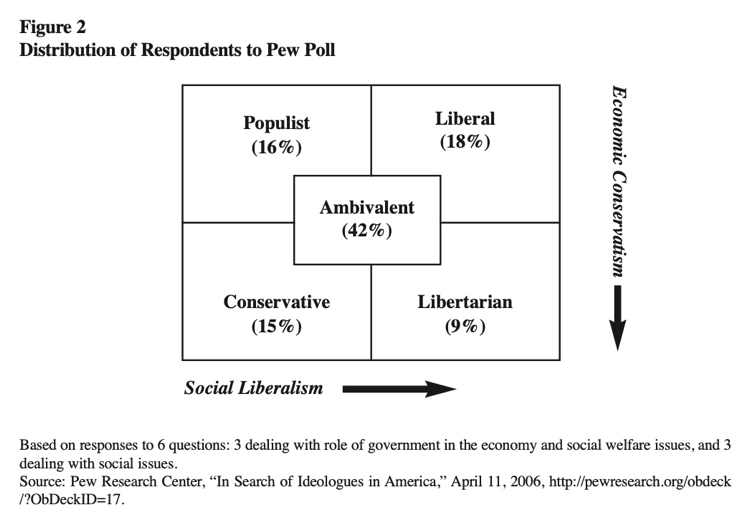

- David Boaz’s “Four-Way Matrix” in 2 dimensions – “social liberalism” and “economic conservatism” – which results in 4 quadrants of Populist, Liberal, Conservative, and Libertarian

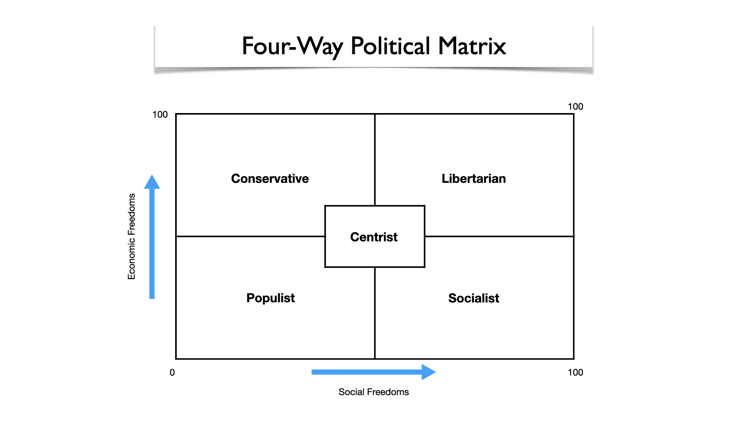

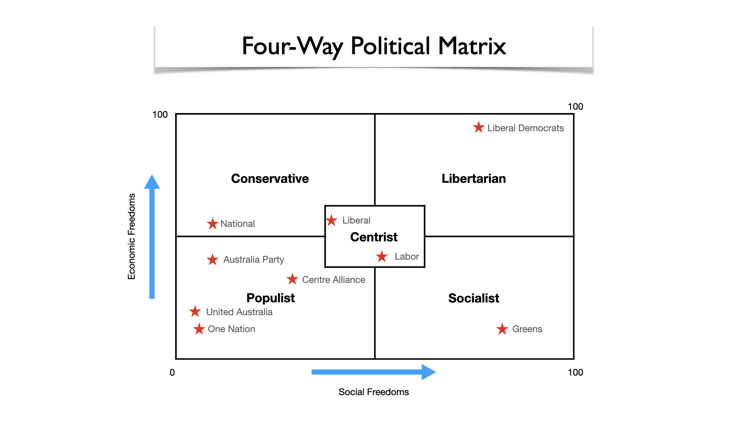

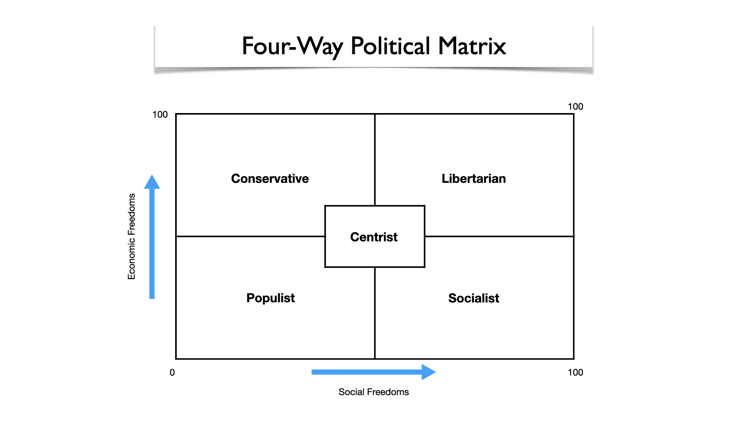

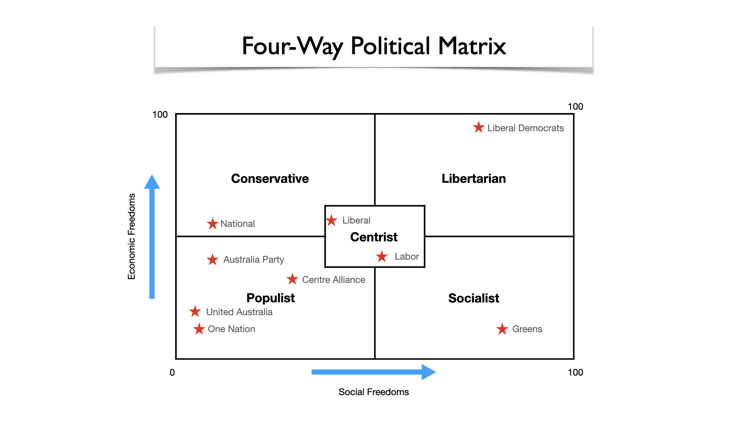

- my own version of the “Four-Way Political Matrix” revised for Australia politics – economic and social freedom – with the 4 quadrants of Conservative, Libertarian, Populist, and Socialist

My last example is a much more ambitious attempt at the “quantification” of the amount of “Human Freedom” by a team from Cato and the Fraser Institute. In their Human Freedom Index they try to quantify the amount of liberty (from 0-10) enjoyed in 165 countries across 82 different “indicators” of personal and economic liberty (thus using 2 dimensions). The results are then ranked by combining the individual scores of “personal liberty” and “economic liberty” into a “Human Freedom” total. One of the very interesting measurements they also provide is to show how different countries have risen or fallen in the rankings over time, giving the index a dynamic aspect which other political spectra or compasses do not.

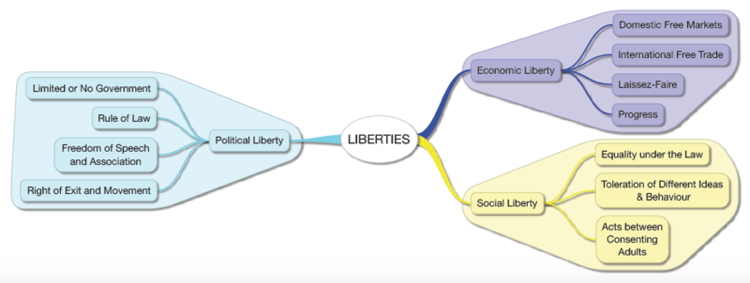

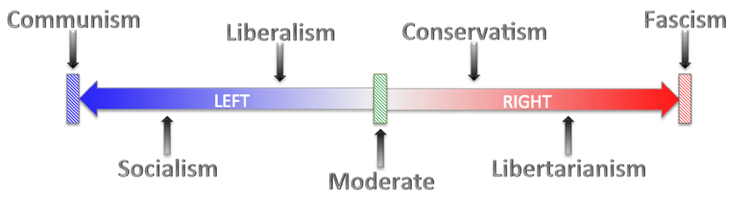

The Traditional “Left-Right” Political Spectrum (1 dimension)

What is wrong with this picture?

This is the most common depiction of the Left-Right Political Spectrum with “communism” and “socialism” on the far “Left” and Fascism on the far “Right”. However, there are many serious problems with depicting in this fashion the different political ideologies and the regimes they give rise to. For example,

- Libertarianism, almost as an afterthought, is placed next to “Fascism” as they are both thought to be be “right-wing”, which is absurd

- there are extreme forms of state power at both ends of spectrum; this implies that CL or “freedom” is somewhere in the “Moderate” centre, and denies CL’s revolutionary and emancipatory heritage

Side Note: since this spectrum was drawn up for an American audience,

- the colours are “wrong”, since the colour red traditionally has been associated with socialism

- there is no “Classical Liberal” position; “Conservatism” is the modern American equivalent

- It uses the American meaning of “Liberal” to mean “left of centre” or “social democracy”, i.e. Democrat

The Origin of the Terms “Left” and “Right”

I have often asked myself this question: When the Revolution comes, on what side of the Chamber/House should the Libertarians sit? On the Left or the Right, or somewhere in between, or should they refuse to take a seat entirely? (for those of you who are anarchists or “voluntaryists”) Of course, part of the answer depends on who is already sitting in the Chamber and who controls the government and for whose benefit.

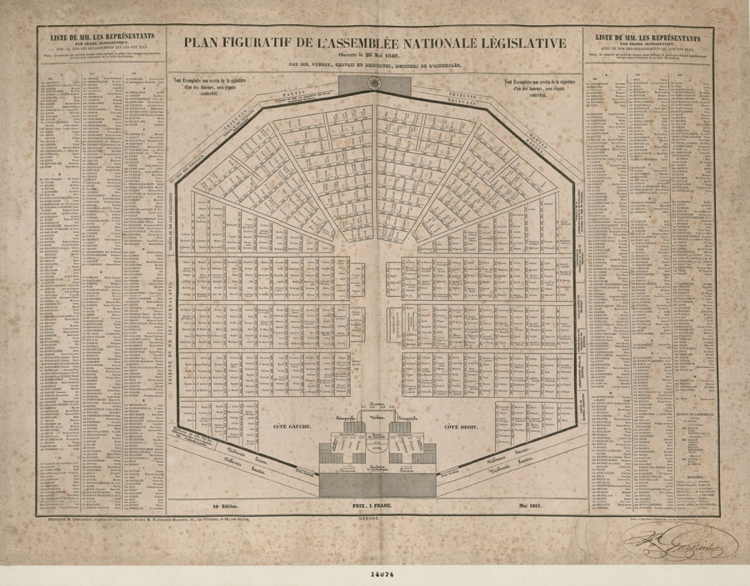

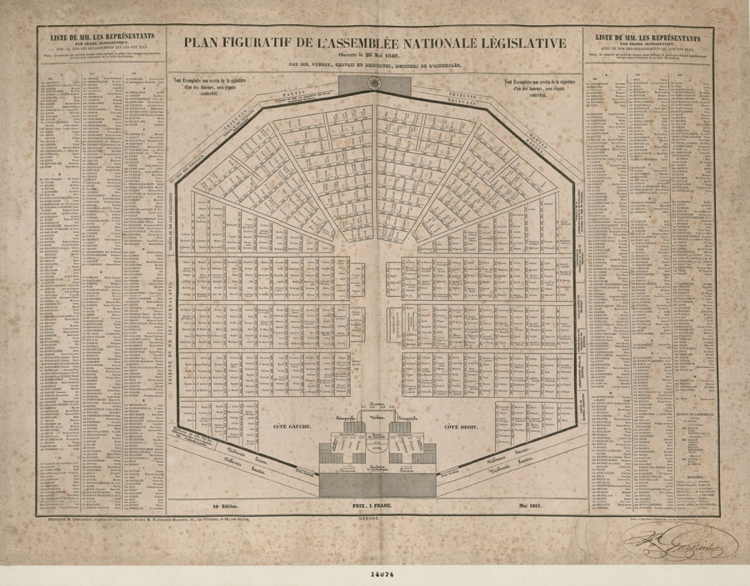

The terminology we use today to distinguish “left” and “right” along a political spectrum has its origins in the French Revolution (as many things do). Those who sat on the Left side of the Speaker in the Chamber opposed the status quo of “throne and altar”, the monarchy (plus the aristocracy and the military) and the established Catholic Church, who sat on the “Right” of the Speaker. Those on the Left supported a range of alternative ideas ranging from crackpot socialism and Rousseau-ianism, to English-style constitutional monarchism, to moderate American style republicanism, and advocates of laissez-faire and the free market. There was a complication to this practice which introduced a vertical component to the seating arrangement. The most radical of the socialists sat as a group high up on the back benches on the Left and so were naturally called “The Mountain” or the “Montagnards” (or Mountain People). Hence my new term of “up-wing” to add to “left-wing” and “right-wing”.

Frédéric Bastiat didn’t know where to sit in the Chamber in 1848

Here is another example of the problematical seating arrangements libertarians face when they get elected. When classical liberalism became a more potent force in the 1840s in England and France and yet another revolution broke in February 1848 the radical classical liberal economist Frédéric Bastiat was elected to the Constituent Assembly to represent his home Département of Les Landes and had to sit in the middle of the Chamber, voting sometimes with the Right to oppose high taxation, government funded make work schemes for the unemployed, and redistribution proposed by the socialist Left; and sometimes with the Left to oppose restrictions of free speech, association (trade unions), and high taxation on basic food supported by the conservative Right. Thus, it would appear Bastiat’s ideas were neither completely of the “Right” nor of the “Left” and this left him in a rather lonely position in a Chamber of 900 elected representatives.

This problem of the etiquette of the proper seating arrangements in the Chamber speaks to a broader issue of what exactly is “libertarianism” or “radical classical liberalism” (I use the terms interchangeably)?

- Is it a leftwing political position (radical in the sense of challenging the status quo) or a rightwing one (in the sense of wanting to “conserve” some or all of the status quo)?

- What are libertarians trying to change and what are they trying to conserve?

- What happens if some of their views are considered to be “leftwing” while others are considered to be “rightwing”?

- Have the ideas of these liberals/libertarians changed over time (or have societies changed)?

- Is the tradition “leftwing-rightwing” political spectrum broad enough to include libertarians, or do we need another dimension or “wing” (“up-wing” or “up-mountain” for example) do do them justice?

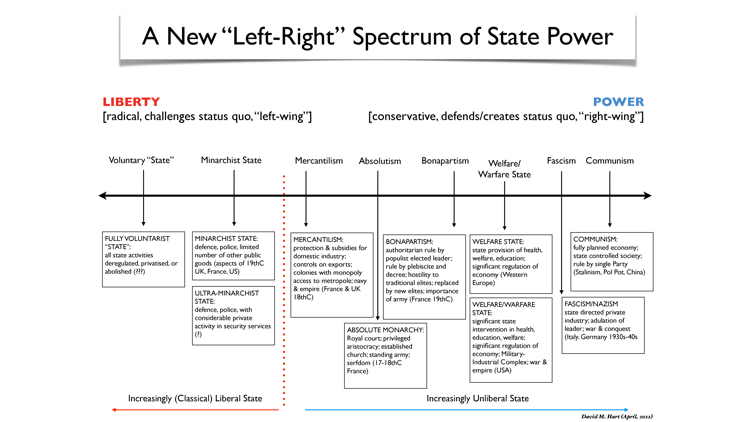

A new “Left-Right” Political Spectrum (1 dimension)

Introduction

What I want to argue here is that the traditional one dimensional left-right political spectrum is completely inadequate both because,

1.) it ignores the complexities of political views and policies in general; most political ideologies are a “bundle” of views of political, social, economic, and other matters, which are linked together more or less consistently ; this is true for the “major” political traditions like “socialism” and CL [see my essays on “What Classical Liberals were For” (13 Aug. 2021) hereand “The Key Ideas of CL” here]. For example, a country might be quite “liberal” when it comes to economics but be very poor when it comes to social and political freedoms (Singapore); alternatively, a country might have considerable political and social freedoms but have high taxes to fund a welfare state (thus reducing its economic freedoms). Even within liberalism itself, I believe we can identify three different sub-traditions (radical, moderate, and “new” liberalism) each of which has a different view of the what the power of the state should be.

2.) in particular it leaves no place for the libertarian position (what I consider to be the heir of the CLT, especially the version I call “radical liberalism”) since libertarians hold some views which are regarded as “rightwing” or “conservative” (low taxes, small government, gun ownership, rule of law), as well as those that are better described as “leftwing” (freedom of speech, association, sexual preference), and those that don’t fit in at all (anti-war, drug laissez-faire, political orneriness / general hostility to everything the government does).

3.) in addition, there are different kinds of “liberty” which need to be taken into account when making these distinctions, both between radically different political ideologies (such as Fascism, Communism, Bonapartism, Welfare State “Liberalism”, Classical Liberalism); as well as within the CL tradition itself (between radical liberals, moderate liberals, and “new” or “LINO” liberals).

Related to this is how the power of the state is exercised. The use of power can be categorised by how extensive its use is, how ruthlessly it is exercised, and by whom it is exercised (and against whom). Regarding extent, power/coercion can be applied comprehensively to every single aspect of our lives (Communism) or only partially in that some things are left relatively free but others are not (modern “Liberal Democracies”). Regarding its ruthlessness, the state can imprison and kill millions of dissenting individuals (Stalinism, Maoism), or governments can threaten, fine, or imprison dissenters but rarely kills them (modern “Liberal Democracies”). Regarding for whom/ on whom, power can be exercised by a particular class (such as aristocrats, crony capitalists, slave owners), or by politicians elected by “the people”.

To help understand these different types of power it is necessary to examine how they impact the different aspects of our lives and “liberties”, or in other words how they impinge upon our political/legal freedoms, economic freedoms, and social/individual freedoms.

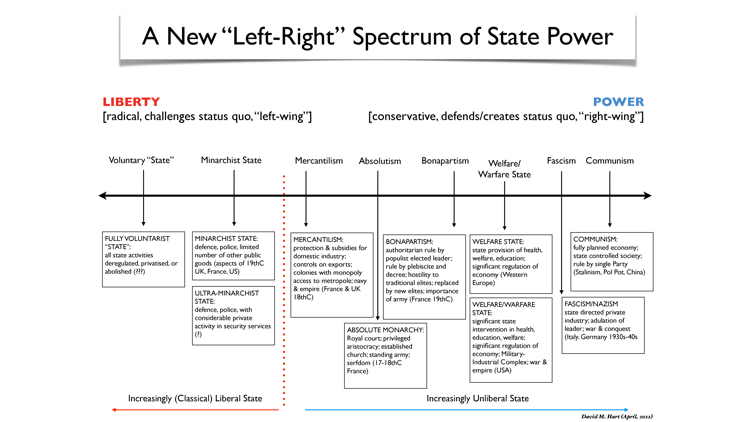

My new “Left-Right” Spectrum of State power

Let me offer here my own revised one-dimension “political spectrum” which attempts to resolve some of these problems by using the two end points of the spectrum as “Liberty” and “Power” instead of “Left” and “Right”.

My “ranking” is based upon a “qualitative” judgment on my part about how “interventionist” or “coercive” different political regimes and the ideology upon which they were based were . It would be useful to “quantify” this like the Cato/Fraser Institute’s do in their “Human Freedom Index” for countries today, but it is beyond my ability at the moment.

On the “Left” (I do this deliberately) there is complete “Liberty” and represent the position which challenges the status quo) and complete “Power” (or Statism) on the right which represents the position which wants to defend the status quo or to create a new one).

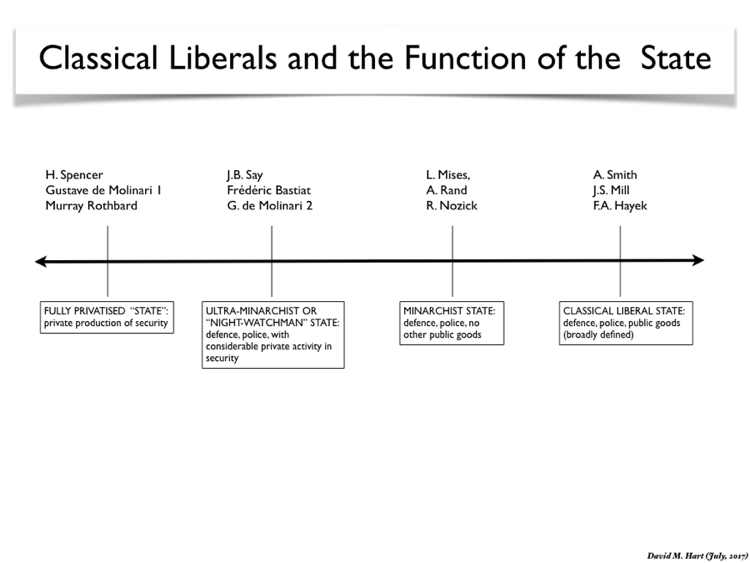

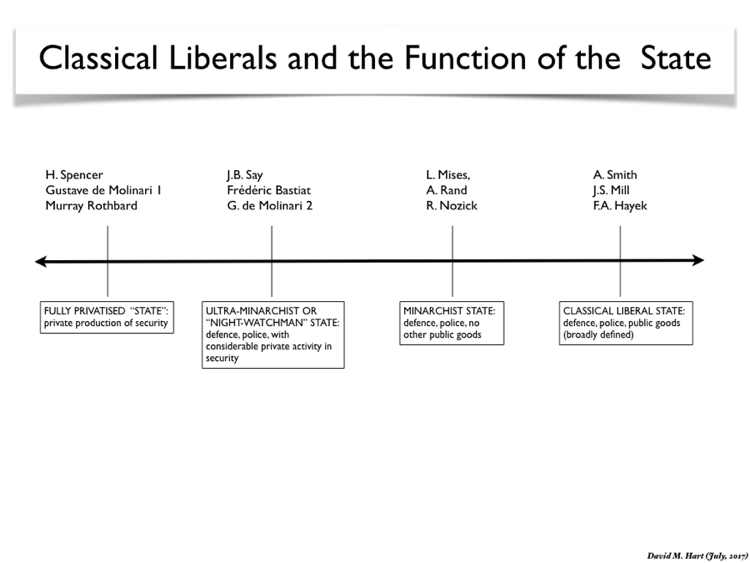

The types of states/regimes which I list here include, at the CL “Liberty” end of the spectrum:

FULLY PRIVATISED OR VOLUNTARIST “STATE”: private production of security, all state activities deregulated, privatised, or abolished [H. Spencer, Gustave de Molinari 1 (younger), Murray Rothbard]

ULTRA-MINARCHIST OR “NIGHT-WATCHMAN” STATE: defence, police, with considerable private or local provision of security [J.B. Say, Frédéric Bastiat, G. de Molinari 2 (older)]

CLASSICAL LIBERAL or MINARCHIST STATE: defence, police, some public goods (broadly defined), and sometimes education [A. Smith, J.S. Mill, F.A. Hayek, L. Mises, A. Rand, R. Nozick]

In contrast, the types of states/regimes which I list at the “Power” end of the spectrum:

COMMUNISM:

fully planned economy; state controlled society; rule by a single Party (Stalinism, Pol Pot, China)

FASCISM/NAZISM

state directed private industry; adulation of leader; war & conquest (Italy. Germany 1930s-40s

WELFARE STATE:

state provision of health, welfare, education; significant regulation of economy (Western Europe)

WELFARE/WARFARE STATE:

significant state intervention in health, education, welfare; significant regulation of economy; Military-Industrial Complex; war & empire (USA)

BONAPARTISM:

authoritarian rule by populist elected leader; rule by plebiscite and decree; hostility to traditional elites; replaced by new elites; importance of army (France 19thC)

ABSOLUTE MONARCHY:

Royal court; privileged aristocracy; established church; standing army; serfdom (17-18thC France)

MERCANTILISM:

protection & subsidies for domestic industry; controls on exports; colonies with monopoly access to metropole; navy & empire (France & UK 18thC)

I find this quite useful as a way of showing how societies have changed over time regarding how free or unfree they are. For example as a result of the “liberal revolutions” of the 18th and 19th centuries American and European societies moved from being less free to more free – thus moving from “right” (statist) to “left” (liberal)., via Absolute Monarchy to Mercantilism to various forms of Limited Government such as Constitutional Monarchy (UK) or Republicanism (US).

In the late 19th and 20th centuries the movement was in the other direction towards increasing state power, so from a Monarchist state (limited government) to Bonapartism, to an increasingly Welfare State and then a variety of state forms such as Fascism, Communism, the Welfare/Warfare state.

The key question for modern-day CLs is whether the direction of the past century can be reversed so that we can resume the movement (progress) towards liberty which took place in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

Admitting a Second and Third Dimension into the Picture: Charts, Compasses, Matrices, a Triangle, and a Cube

David Nolan’s Libertarian Spectrum” (1969)

Given the acknowledged weaknesses of the traditional “Left-Right” 1-dimensional spectrum, one solution is to use a 2 or 3-dimensional diagram (or more dimensions if you can understand the higher mathematics of multi-dimensional spaces), such as one dimension for economic liberties, another for political liberties, and a third for “personal” or “social” liberties. Two examples of this approach is David Nolan’s “Chart” (1969) and the commonly used today “Political Compass”.

David Nolan was one of the founders of the American Libertarian Party and it was an attempt to show how the libertarian ideology fitted into the broader political picture of America in the 1960s and 1970s, since it was largely ignored by the mainstream journalists and political scientists. Nolan’s Chart has come down to us in two versions, his original Chart of 1969 and a “simplified version which followed soon afterwards.

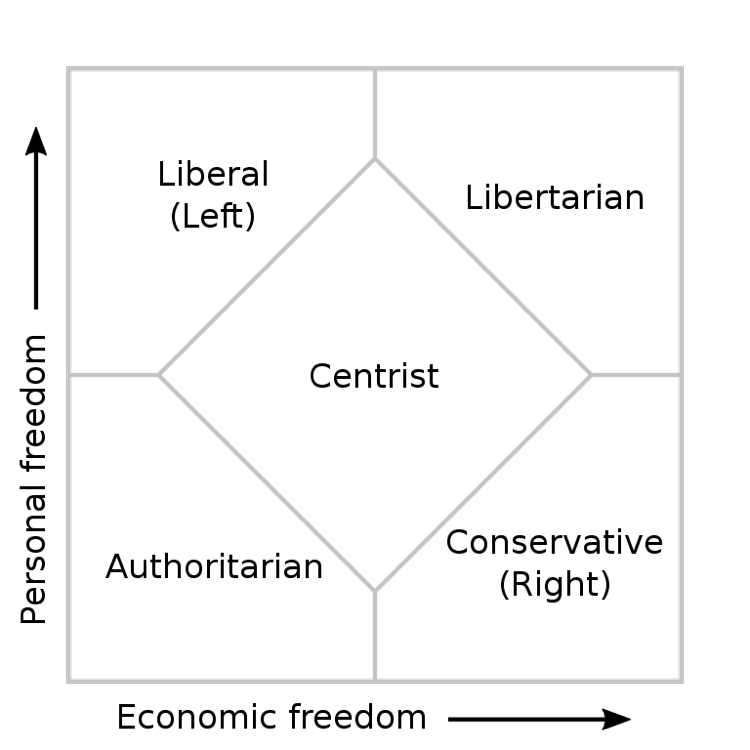

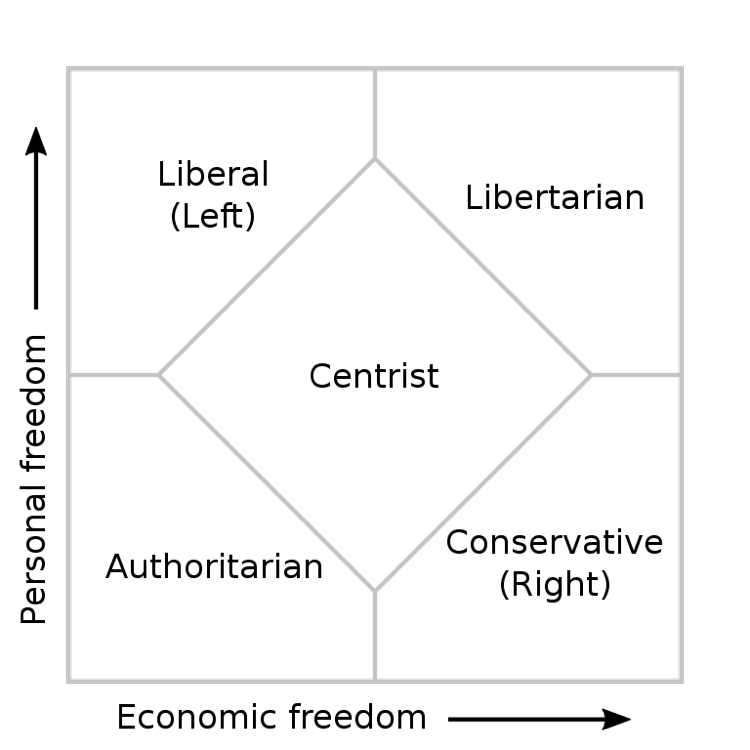

Nolan’s original Chart had 2 axes: a horizontal x-axis which was “Left” (Liberal) or “Right” (Conservative) and a vertical y-axis which had “Libertarian” vs. “Authoritarian”. Rather confusingly, there it also depicted two different kinds of “Freedom” (Personal and Economic) which sloped at an angle

A “simplified” version of the Chart was created to untangle some of this confusion. The main square was rotated to the right and had as its two axes a horizontal x-axis showing the degree of “Economic Freedom” (from 0-100) and a vertical y-axis for “Personal Freedom” (from 0-100) . The main square was divided into rough quadrants with a large square in the centre for the “Centrist” position. The four quadrants include the traditional categories of Liberal (Left), Conservative (Right) , as well as two new ones Authoritarian and Libertarian.

The “Political Compass” (2001)

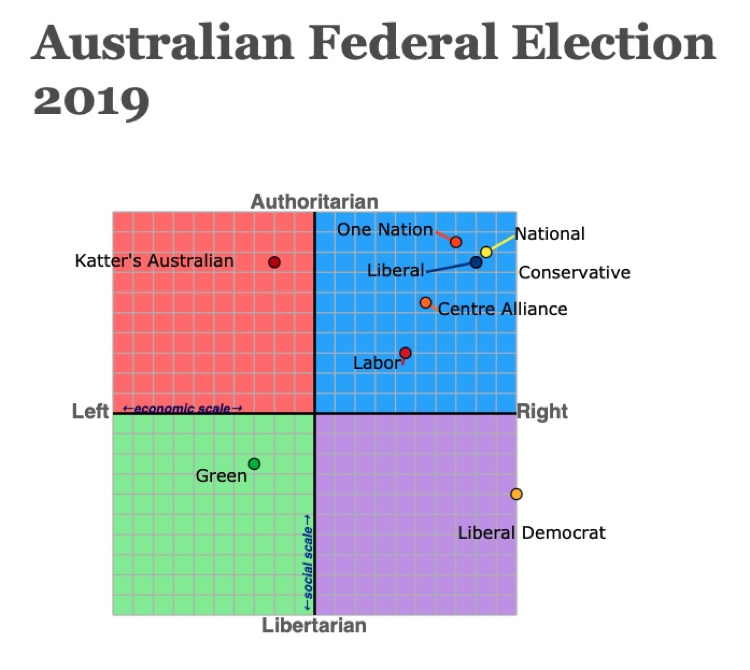

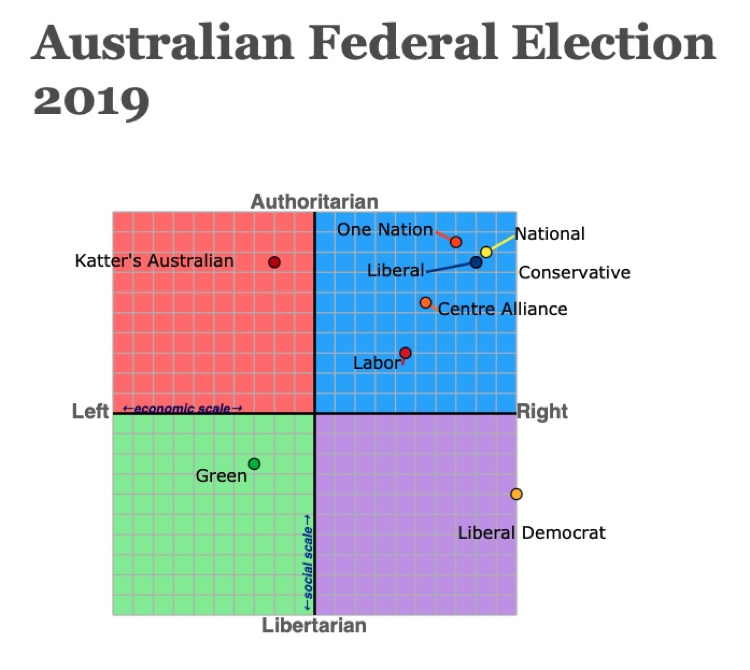

Quite similar to Nolan’s Chart is the commonly used “Political Compass” which also uses “quadrants” in which political parties are placed. The horizontal x-axis is again “Left” vs. “Right”; and the vertical y-axis is “Authoritarian” vs. “Libertarian.” An Australian “Political Compass” was created by for the 2019 election in which the main political parties are labelled. Most of the parties are clumped together in the top right quadrant (Authoritarian-Right. The libertarian Liberal Democrat Party is all alone in the Libertarian-Right quadrant.

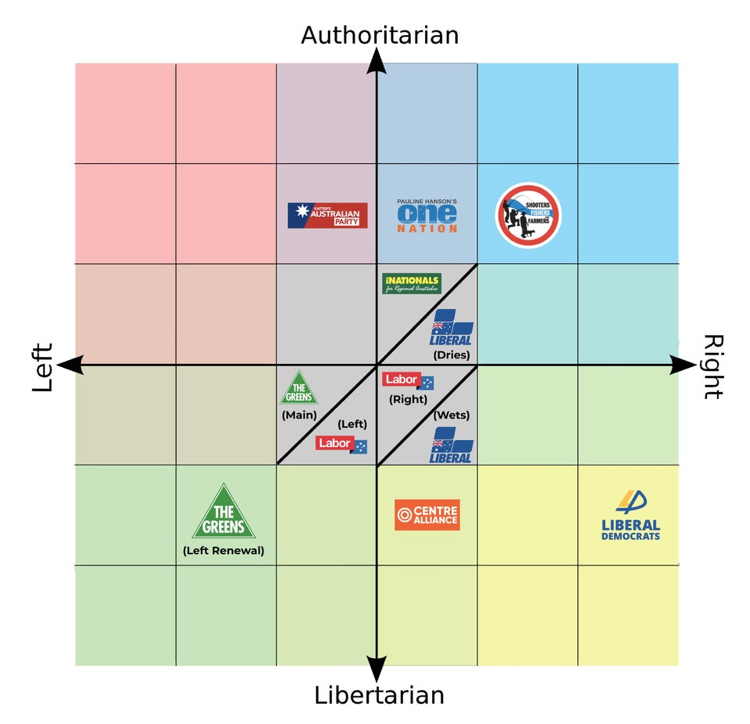

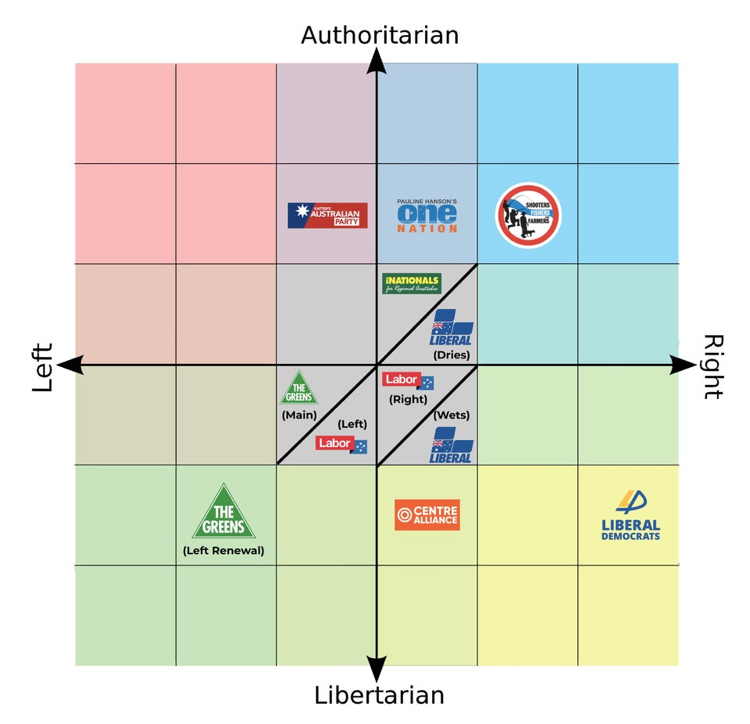

Another version for Australian political parties is below. It is more nuanced in that it tries to show the factions within the Greens (the main party and the “Left Renewal”), Labor (the right and left factions) and the Liberals (Dries (economic “rationalists”) and Wets). Another difference is that they locate all the main parties around the centre, thus identifying them as “Centrist”.

[See below for my version of this for Australian political parties.]

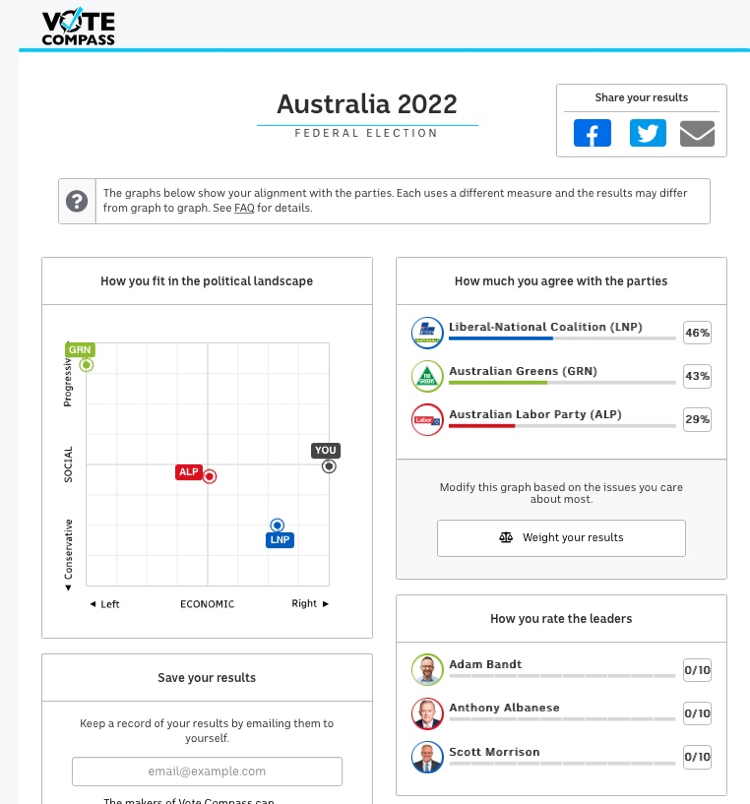

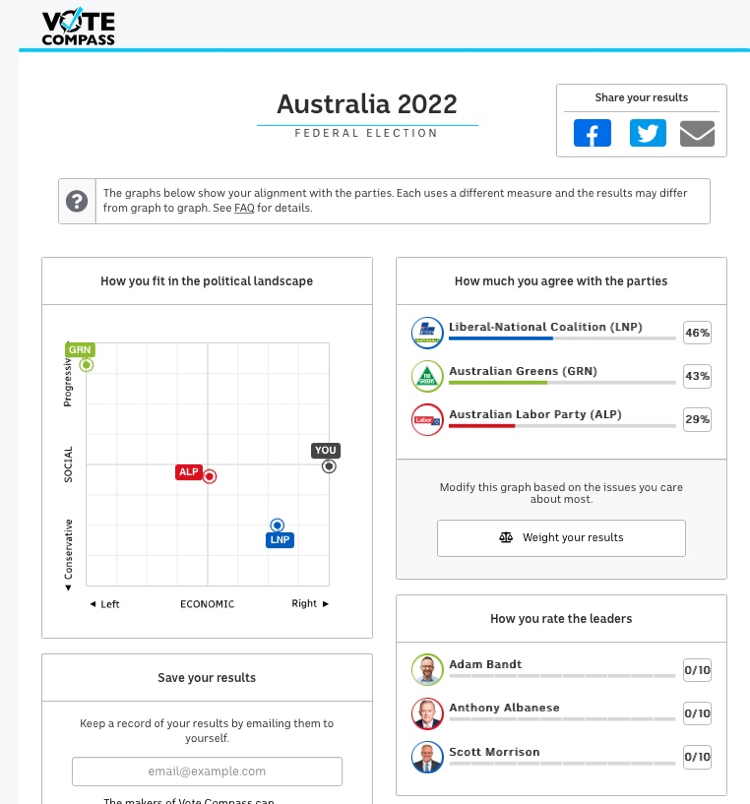

There is also a variation of this used by the ABC called the “Vote Compass” which has 2 dimensions: “Social” (conservative vs. progressive) and “Economic” (left vs. right). They have updated it for the 2022 election for the 2022 election – Election season has arrived and Vote Compass is back – ABC News.

I completed the questionnaire, and was ranked 100% “right” on the economics x-axis and zero on the “Social” y-axis.

David Boaz’s Four-Way Matrix

David Boaz (VP at the Cato Institute) further developed Nolan’s Chart in order to measure the “libertarian” vote in American elections which was not being captured by tradition ways of measuring voter’s values, since the mainstream continued to divide the political world into two main camps – liberal vs. conservative; or Democrat vs. Republican.

Boaz created a modification of David Nolan’s “simplified” chart in his article analyzing the state of play in the US in 2006:

David Boaz and David Kirby, “The Libertarian Vote” (October 18, 2006) Cato Policy Analysis No. 580.

The two axes are “Social Liberalism” and “Economic Liberalism” but the chart is not well designed (the x and y axes usually start at zero at the bottom left)

I have reworked this slightly to make it clearer and to use Australian political terms. Here is my version which I call the “Four-Way Political Matrix”:

And here is my attempt to place Australian political parties in this matrix. There is a clustering of parties in the “Populist” quadrant, the “Centrist” position is populated by both the 2 major parties, and there is only one party in the “Libertarian” quadrant. This shows how “interventionist” all the Australian political parties are

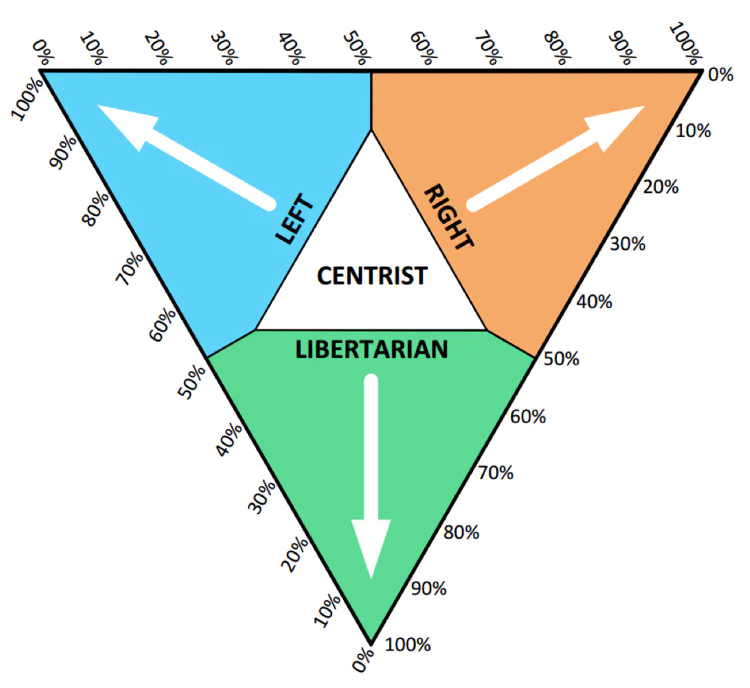

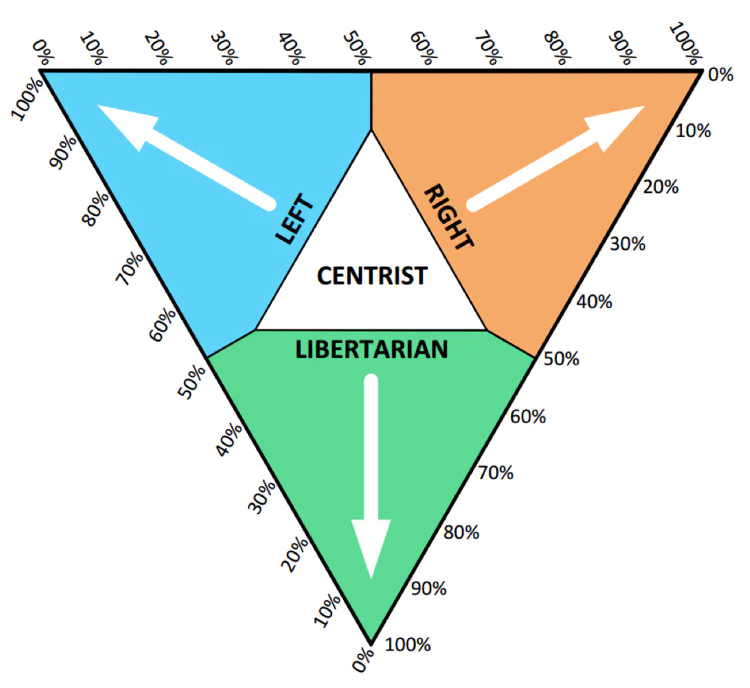

Nick Kastelein’s Political Triangle

As many commentators have pointed out, none of these “compasses” are very useful as they do not capture the complexity of political belief or voter behavior on a variety of issues. See for example in the Australian context, the critique by Nick Kastelein writing in The Spectator in 2018, who argued that the libertarians (the “other right” as he calls them) were once again being left out.

Nick Kastelein, “The other right: what’s wrong with the Political Compass” The Spectator Australia (17 Oct. 2018) Online.

However, his “political triangle” designed to reveal this “other right” is not very adequate either:

A common problem for these “compasses” and “matrices” is that they persist in using the Left-Right spectrum as their starting point, even though as I have tried to show above, this is problematical and mostly unhelpful in understanding the true/real differences between CL and other political ideologies.

A 3-Dimensional “Spectrum” or “Cube”

One enterprising author, Kelley Ross, has tried to create a 3-dimensional political spectrum (or rather a “cube”) in order to plot political ideologies according to the three main kinds of freedoms/liberties we are interested in: economic liberty (on the x axis), personal liberty (on the y axis), and political liberty (on the z axis)

Kelley L. Ross, “Positive & Negative Liberties in Three Dimensions” (1996) . Online.

This was an heroic effort but ultimately unreadable. I hope someone skilled in graphic art and design might be able to do a better job because the underlying idea is a sound one.

Quantitatively Speaking: The Cato/Fraser “Human Freedom Index”

The work of Vásquez et al. for the Cato and Fraser Institute’s annual “Human Freedom Index” is sensitive to this problem of complexity in their ranking of 165 countries according to the amount of freedom they enjoy.

The Human Freedom Index 2021. A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil, and Economic Freedom. Ian Vásquez, Fred McMahon, Ryan Murphy, and Guillermina Sutter Schneider (Cato Institute and Fraser Institute, 2021). Online – Human Freedom Index: 2021 | Cato Institute and PDF. Note: the Introduction to the volume is well worth reading.

The HFI uses a libertarian Lockean definition of liberty in their assessment. They state that :

pp. 9-10: The contest between liberty and power has been ongoing for millennia. For just as long, it has inspired competing conceptions of freedom. … Freedom in our usage is a social concept that recognizes the dignity of individuals and is defined by the **absence of coercive constraint**. … Freedom thus implies that individuals have the right to lead their lives as they wish as long as they respect the equal rights of others.

The IHF uses a rough 2-dimensional approach, ranking each country according to “Personal Freedom” and “Economic Freedom”, based upon 82 “distinct indicators” which fall into the following 12 areas:

- Rule of law

- Security and safety

- Movement

- Religion

- Association, assembly, and civil society

- Expression and information

- Relationships

- Size of government

- Legal system and property rights

- Sound money

- Freedom to trade internationally

- Regulation

Here are some of the findings of the Index.

The Top 30 Countries (note NZ is no. 2, Australis is 8 (down 4), UK is 14 (down 3), and US is 15; Singapore is quite low because of its lack of political and social freedoms at 48 (economic freedom is 2, but personal freedom is 88))

The Freedom Index for Australia:

Again, this is an heroic attempt to bring some order and understanding to a very complex state of affairs. I would like to see two additional main categories of assessment, namely “Political Freedom” and “Legal Freedom” to make it a bit more finely detailed and complete.

The authors admit that their ranking is incomplete because it leaves out a number of factors which I think are important if we want to get a better picture of the state of freedom in the world.

The editors admit that they can’t assess freedom to use drugs as they do not have consistent data. They also leave out (or do not specify up front) other examples of “prohibition” (like alcohol, cigarette advertising, or abortion) which I believe are serious violations of individual liberty. They also leave out other things like

- conscription (a form of temporary slavery)

- deliberately punitive taxes on (or outright prohibition of) so-called “sin” or “vices” like alcohol, cigarettes, and increasingly petrol in order to discourage their use and thus modify people’s behaviour

- states which invade, bomb, blockade other countries (another kind of “intervention”)

- compulsory voting

I think any true assessment of “freedom” needs to take these additional factors into account.

The Consequences for CLS today

There are several consequences which follow from thinking about the political spectrum and the multi-dimensional nature of liberty in these ways:

- it helps us identify better who we are, what we believe, we we came from, and where we are heading

- it helps us see how we differ from other political groups and ideologies, what we have in common, and what we do not; who are our potential allies and who are are main opponents

- it shows us where there might be opportunities for alliances between libertarians and other groups who share one or two of our ideas but not all of them; there are opportunities to align with those on “the left” on some issues, and with “the right” on others; I call this “triangulation” (based upon the tactics of Pres. Clinton)

- it provides a strategy for arguing with friends and colleagues; if they come from “the left” begin talking to them about things we share with them and once you have won their trust it might be time to gently broach “right wing” issues which they reject but you believe in (and vice versa for those on “the right”)

Until libertarian ideas are accepted by the majority (an unlikely event in my view anyway) this might be best we can hope for in the medium term if we want to spread our ideas to a broader audience and to engage our political opponents in debate.