The Cover Art of Boétie’s Discourse

I was drawn back to Étienne de la Boétie’s wonderful essay on “Voluntary Servitude” (written c. 1550, published 1576) because of recent events. Boétie asked perhaps the most fundamental question of political theory, namely, why does the majority allow itself, even asks for it , to be ruled by a small minority of people (a sovereign monarch, politicians in Parliament, the bureaucrats who run things, and the technocrats who advise the government). They allow this rule over them even when it is at their own expense in terms of their own property, the jobs they work or businesses they run, their freedom of movement and congregation, and even the ideas they are permitted to believe in or discuss.

As he put the question at the beginning of his essay:

I would only understand how it is possible and how it can be that so many Men, so many Cities, so many Nations, tolerate sometimes a single Tyrant, who has no Power but what they give him; who has no Power to hurt them but only so far as they have the Will to suffer him; who can do them no Harm except when they chuse rather to bear him than contradict him. A wonderful Thing, certainly, and nevertheless [5] so common, that we ought to have more Grief and less Astonishment, to see a Million of Millions of Men serve miserably, their Necks under the Yoke, not constrained by a greater Force but, as it were, enchanted and charmed by the single Name of one, whose Power they ought not to be afraid of, since he is alone, nor love his Qualities, since he is with regard to them inhuman and savage. Such is the Weakness of Mankind.

… BUT, good God!—what can this be? How shall we call this? What Misfortune [7] is this? What sort of unhappy Vice is it, to see an infinite Number, not only obey, but serve, not governed but tyrannised, having neither Goods, Parents, Children, nor Life itself which can be called theirs? To bear the Robberies, the Debaucheries, the Cruelties, not of an Army, not of a barbarous Camp, against which we ought to spend Blood, nay even our Lives, but of one Man : not a *Hercules* or *Sampson*, but a little Creature, and very often the most cowardly and effeminate of the whole Nation : One not accustomed to the Smoak of Battles, but scarcely to the Dust of Tilts and Tournaments

So, I decided to gather all the material I had on Boétie and put it online. Over the past few weeks I have put online 9 different versions of the essay – 5 in French (c. 1560s, 1576, 1577, 1892, 1922) and 4 in English translation (1735, 1942/1975, 1966). I also built two pages so one could view the different texts side-by-side. One is the 1922 illustrated version by the Catalonian engraver and typographer Louis Jou (1881-1968) with the illustrations surrounding the text on the left and a modern (also 1922) French version on the right. The second allows the reader to compare many of the different texts side-by-side, either French or English, or either on the right or on the left (depending on what is being compared).

As I searched online for various editions I came to realise two things; one, was that there have been more editions (especially in French) than I had realised; and secondly, that many of these editions had striking cover art. I arranged these covers by theme: chains and cages, classic portraits and art, oppressed figures and their oppressors, minimalist design and abstract art, cartoons and drawings, and advertising for events or performances

Below is a small sampling of what I have found. See this other page for the full collection.

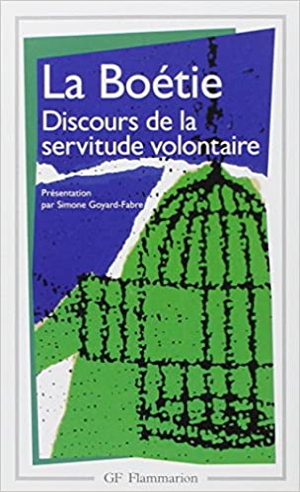

An edition by Flammarion (Jan. 1993) with a roughly drawn empty bird cage with the door open. It suggest that if we could only refuse to voluntarily grant servitude to the state, then we could fly away free as a bird.

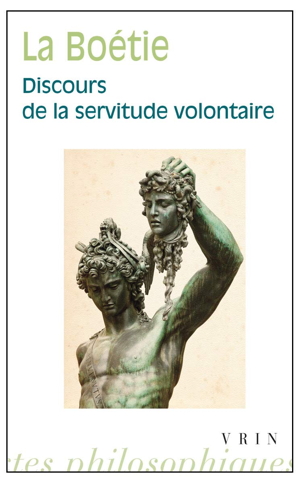

An edition by Vrin (Oct. 2014) with essays by André Tournon and Tristan Dagron. The image is Benvenuto Cellini’s statue of “Perseus with the Head of Medusa” (1545–1554). Perseus has beheaded the Gorgon Medusa whose hair is made up of snakes and who turns to stone anyone who looks at her. This is an unusual choice of image as Boétie did not advocate violent resistance to the state (like chopping its head off) but rather non0violent, passive resistance by withholding cooperation.

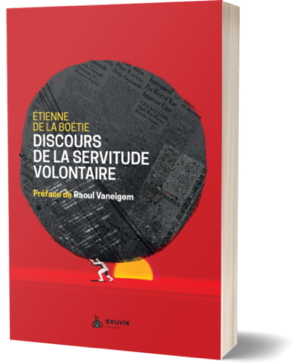

An edition by “Exuvie” (no date) with a preface by the Belgian anarchist Raoul Vaneigem. The image is of a very small figure of Atlas carrying on his shoulders a very large rock. It is interesting that the left have also seized upon Boétie’s essay. The German socialist anarchist Gustave Landauer translated it into German in 1910 and this Belgian anarchist wrote an introduction to this more recent edition. What struck me was the Randian connotation of the image: Boétie was in fact urging Atlas to “shrug” off the burden of the state in order to be free.

Another socialist version of Boétie. This is a German edition by Malik-Verlag (1924). It has a cover by the artist Georg Grosz which shows a submissive worker standing before a rich capitalist who is enjoying the finer things of life. Servitude according this interpretation is a result of working for wages within the capitalist system. Freedom will thus come about when the workers’ go on strike and overthrow the system in a socialist/Bolshevik revolution.

This edition by Payot (2016) shows the classic illustration from Thomas Hobbes’ book Leviathan (1652). The “leviathan” monarch’s body is composed of thousands of small figures of his subjects. If the individuals which made up the Leviathan’s body decided to walk away or do something else, then the “body politic” would collapse and the Leviathan would then no longer exist.

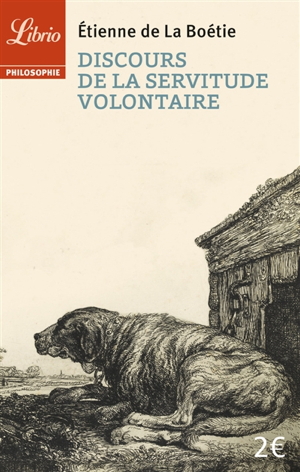

This is a striking but rather cryptic cover for the edition by Librio (Sept. 1993). It also contains Benjamin Constant’s “De la Liberté des Anciens et les Modernes”, and La Fontaine’s fable of “The Wolf and the Dog” (hence the cover illustration of the dog). In Fontaine’s fable the wolf was wild, free, but hungry; the dog was domesticated and well-fed but had the scars of the collar it wore around its neck. Thus people, by implication, can either lead a free but uncertain life (like the wolf), or have the security, regular meals, and shelter enjoyed by a house-trained and domesticated dog, but the sot of this is having to wear a collar and come at the master’s whistle or call.

Being a text-oriented person, I found this edition by Bouchene (Jan. 2015) beautiful, elegant, and clean. The cover shows the opening paragraphs of the Mesmes manuscript edition.