I would add a few more conditions to the very useful list Don drew up yesterday. These are

- the principle of proportionality

- the principle of consistency

- the principle of the “unseen” and unintended consequences of this intervention

- the principle of the impossibility (or great unlikelihood) of rational economic calculation by government planners

- the “precautionary principle” concerning state intervention

The principle of proportionality is that all risks should be treated according to the degree of their severity and their likelihood of occurring. One of the things that became clear very early on in the covid epidemic was that different age groups were affected very differently by the virus, and that some groups’ risk of serious illness or death was statistically insignificant (children and young adults), while others were at considerable risk of death (those over 70 who had other severe health problems). As with every other government regulation, a one-size-fits all policy is crude and unjust and usually causes more harm than good. Hayekian “local knowledge” is needed in order to address this issue and this is something government most unlikely to be able to provide. Furthermore, the effort and cost we should spend to counter a risk should be proportional to that risk, and in the case of old and sick people near the end of life, they and their families should make that decision not the state.

The principle of consistency is that like risks are treated alike. It has struck me as absurd that people would overreact to a risk which is less dangerous than other things the risk of which they have accepted for years or have only taken minimal steps to mitigate or avoid. In the case of covid, for most people it does not rank at the top of risky activities (such as driving a car, or walking down a dark street in the inner city) or the most common causes of death (over eating and drinking, lack of exercise, suicide) which they routinely engage in or accept. To be consistent, if the state is allowed to ban risky behaviour it should start at the top of this list and work its way down. If more people will die from heart disease or car accidents, for example, than covid, then the state should start by regulating or banning what food we can eat or liquids we can drink, or how much exercise we should have each week; or impose a “lockdown” on car usage to reduce car accidents; only then should it address the problem of covid by making the wearing of masks compulsory and imposing draconian “lockdown socialism” to restrict movement or public gatherings.

The principle of the “unseen” and unintended consequences of this intervention. According to this principle, it is almost certain, though not entirely predictable in all its details, that there will be Bastiat-ian “unseen” consequences to any state intervention. These may range from “economic” (increased costs, distortions in production and consumption), to “political” (the politicians who enact the legislation come to like their increased power and may well become corrupted as Acton predicted ted), or “moral” (individuals become increasingly used to and dependent upon government to “do something” to make them “safer”, and voluntary solutions are not undertaken as a result), to “medical” (resources which would have been devoted to assisting those who will die in large numbers of other diseases such as malaria, TB, diarrhea, or aids, are now diverted to finding a rushed vaccine for the new corona virus), and the now increasingly recognized “domestic” consequences (lockdowns increase death and injury within the home from depression, drug abuse, domestic violence, suicide).

The principle of the impossibility (or great unlikelihood) of rational economic calculation by government planners applies just as much to government public health and hygiene planners as it did to Stalinist central planners. Thus, it is up to advocates of government intervention to demonstrate how the central planning of the health economy in particular and the broader economy in general can avoid the fatal problems identified exactly 100 years ago by Mises in his essay “Economic Calculation under Socialism” (1920). Fort example, how is the distinction between “essential” and “non-essential” economic activity even possible in an economy as complex as ours? How do you avoid the problem of the overproduction of ventilators (which turned out not to be needed and in fact harmed the patients who were forced to use them), or the overproduction of temporary “Nightingale hospitals” in England or the underused naval vessels in New York harbor?

The “precautionary principle” concerning state intervention

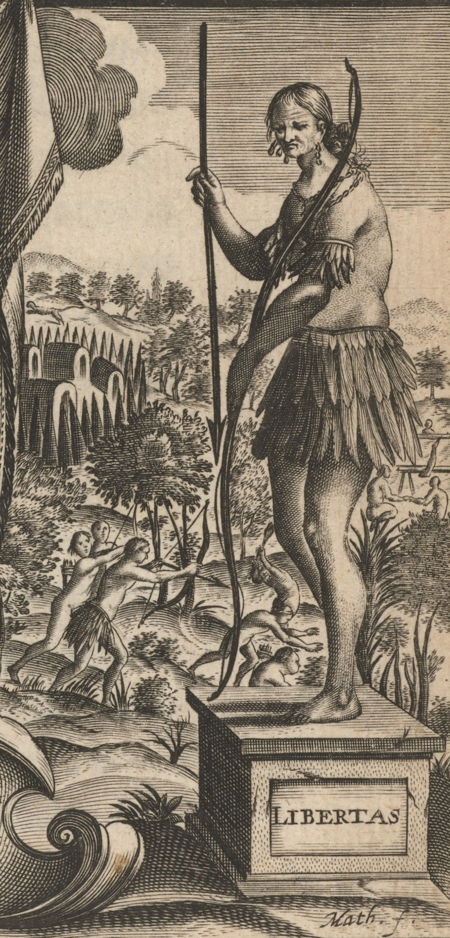

is that great caution should always be applied to permitting any acts of intervention by the state. We as libertarians and free market economists know that government intervention is coercive and thus violates individuals’ rights to liberty and property, that it often fails to achieve its objectives or even produces results the opposite of those it intended, that by the “ratchet effect” the state increases in size and power with every crisis and never returns to its previous level, that its actions often produce “collateral damage” including loss of life, etc. Thus, according to my new libertarian “precautionary principle” we should avoid at almost any cost allowing the state to intervene to “solve” problems. That is of course, if we value liberty, peace, and prosperity, and this gets to the nub of the problem, since it is now quite obvious that most people rank “safety” far ahead of liberty in their list of preferences. This has been the tragedy of 2020 which has made this preference abundantly clear.

I would argue then that all of the above “principles” inevitably leads us to conclude that there should be “the presumption of government failure” to complement “the presumption of liberty” when assessing whether or not the state should intervene in public health, or in any other matter.

Note: Don Boudreaux picked it up and published it on Café Hayek – “And a Presumption Also of Government Failure” Café Hayek (31 Dec. 2020) – with the following comment: I’m honored that the Australian political philosopher and historian of ideas David Hart expanded so wisely and so fruitfully on my recent post on Covid-19 and the presumption of liberty . I share below, in full, David’s essay, which he sent to me my e-mail.