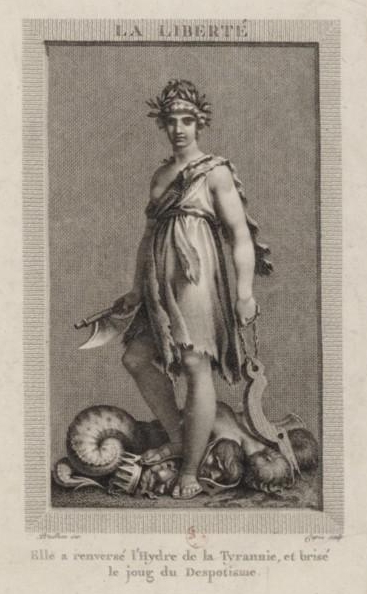

[Liberty has overturned the Hydra (monster) of Tyranny and smashed the yoke of Despotism (1793)]

[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

Several CL/L thinkers have regarded the efforts of groups of people over the past 400 or so years to create a freer society as a general and long-term “struggle” between Liberty and Power (Rothbard), or a series of “classical liberal crusades” (Ebeling) against various forms of institutionalised coercion and legal privilege.

MNR believes that throughout history there has been a struggle or “race” between the “Old Order” of privilege and plunder which he calls “Power”, and the new emerging order of free and emancipated individuals who live together and interact with each other via voluntary association and exchange and mutual respect for each other’s rights to LLP (life, liberty and property), or what he refers to collectively as “Liberty”. This struggle, Rothbard believes, takes place on an ideological level as a battle of ideas between those who justify the action of the state and its rulers on the grounds of “divine right,” tradition, the greater wisdom and knowledge of the elite who rule, or just mere expediency; and those who defend the ideas of natural rights, individual liberty, free markets and free exchange, productive labour, and peaceful coexistence. The struggle also takes place on a political level as those who wield Power are reluctant to give up their privileges, and those who seek Liberty resent the impositions which are made upon them and the violations of their rights to LLP. Now and again these two struggles, ideological and political, come together to produce a shift in the relationship between the forces of Power and the forces of Liberty, which on several occasions has resulted in the advance of Liberty and the retreat of Power. [See his essay “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” (1965) and Preface to FNL “The Libertarian Heritage: The American Revolution and Classical Liberalism” (1978).]

The best example of this struggle between Liberty and Power took place within the English-speaking world (the Empire and metropole) in the 140 years between the 1640s and the 1780s which saw three major revolts or revolutions led by “liberals” (although they did not call themselves by that name) seriously challenge and weaken the Power of the state. These challenges to state Power were the English Civil Wars and Revolution of the 1640s (with ideas drawn from the work of Edward Coke and Levellers like Richard Overton and John Lilburne), the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 (John Locke and the Whig party), and finally the American Revolution of 1776-1783 (Jefferson, Madison, Paine, et al.). On the strong connections between these “three British revolutions” see the collection of essays Three British Revolutions: 1641, 1688, 1776. Edited by J.G.A. Pocock (1980).

The most important of these “liberal revolutions” in MNR’s view was the sometimes quite violent American revolution, which he regards as a “classical liberal” revolution, and the less violent, more peaceful evolution of liberal institutions in late 18th and early 19thC, first in England and then later spreading to other parts of Europe (and their colonies like Australia and Canada). As the pamphlets of the period (1750s-1770s) clearly show, the ideology which motivated the rebels and revolutionaries was an explicitly liberal one and they shared MNR’s view that it was a struggle between the “liberty” of the British colonists and the “power” which the Crown and its officers wielded in the north American colonies. [See Bernard Bailyn, “Power and Liberty: A Theory of Politics” in The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1992), pp. 55-93; and Bernard Bailyn, “The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,” in S. Kurtz and J. Hutson, eds., Essays on the American Revolution (1973), pp. 26–27.]

What is interesting to note is that this struggle resulted in a nearly 100 year period of revolutions and upheavals across the entire “Trans-Atlantic” world where liberal, enlightened views about individual liberty, responsible and limited government, and free markets were put into practice with varying degrees of consistency and success. This is well discussed by historians like Robert Palmer in The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Challenge (1959) and The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Struggle (1964). Although, the incomplete nature of this revolutionary movement to achieve all its aims has been stressed by Jonathan Israel in The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848 (2017), and The Enlightenment That Failed: Ideas, Revolution, and Democratic Defeat, 1748-1830 (2019).

Richard Ebeling has a similar view which he describes as a series of “classical liberal crusades” for liberty. The passion with which CLs of this period engaged in these emancipatory movements justifies their being called “crusades”. For some, it was based upon their deeply held religious sensibilities (such as the Quakers’ desire to end slavery and war), while for others it was more secular and based upon their ideas of the justice of self-ownership, voluntary exchange and association, and private property, and their passion to enjoy these things for themselves as well as, most importantly, to extend them to others.

These “crusades” were more like individual campaigns in the broader liberal “battle” for emancipation. Whereas Rothbard focuses on the American Revolution which sought systemic change in the way entire societies were governed, the liberals who were active in these “crusades” sought to change only one, perhaps very glaring, injustice at a time.

The five CL “crusades” Ebeling identifies are the following:

1. the crusade against coerced labour such as slavery and serfdom (the abolitionism)

2. against the arbitrary authority of kings and princes (republicanism and the rule of law)

3. against restrictions on trade and industrial activity (free trade and deregulation)

4. against strict limits on who could participate in political activity (democracy) and

5. against war and conscription into the army (peace).

Below I have slightly reworded his more detailed description which he provides in his essay “The Beautiful Philosophy of Liberalism” (2018) and his book For a New Liberalism (2019), chap. 1 “The Classical Liberal History and Heritage of Freedom,” pp. 15-26 [on the “crusades pp. 19-25]:

The Five Great Classical-Liberal Crusades for Liberty:

1.) First was the freedom of the individual as possessing a right of self-ownership. [and against slavery]

2.) The second great classical-liberal crusade was for the recognition of and legal respect for civil liberties. [no unwarranted or arbitrary arrest and imprisonment; freedom of thought and religion, freedom of speech and the press, and freedom of association; the rule of law (justice was to be equal and impartial, and that all were answerable and accountable before the law, even those representing and enforcing the law in the name of the king)

3.) The third great classical-liberal crusade was for freedom of enterprise and free trade. [end of mercantilism (the system of government planning was then called)]

4.) The fourth classical-liberal crusade was for greater political liberty. [participation in choosing rulers – enlarged voting franchise]

5.) Finally, the fifth of the classical-liberal crusades of the 19th century was for, if not abolishing war, then at least reducing the frequency of international conflicts among nations and the severity of damage that came with military combat. [protect non-combatants, treatment of POWs, banning certain forms of warfare

These crusades for liberty began in the 17thC and continued until the mid- to late-19thC at which time Ebeling believes the CL movement lost its way and began to become both more conservative (or “moderate” in my terminology), that is to say it was content to sit on its laurels and not to pursue these crusades to their logical conclusions, and to drift towards socialism (i.e “new liberalism”) and other state-based solutions to the “social problems” which continued to plague European and American society.

For example, although there were some CLs (Condorcet, JS Mill) who advocated the right of women to own property, work for a living outside the home, attend college or university, enter any profession or trade they wished to, sign contracts, dissolve their unhappy marriage, and vote in elections and stand for election, the broader CL movement did not take up this movement for the emancipation of women with the same passion they had shown in the movement for the abolition of slavery or for free trade. In other words, it did not become another “classical liberal crusade” so other ideological and political groups took it up and made it their own.

The same could be said about the rights of indigenous people in the colonies run by the European powers (Britain and France) or the plight of ex/freed slaves in the US after the Civil War. Again, except for a handful, most CLs believed the colonised indigenous people were “lesser” or inferior human beings who were not yet ready for full participation in a more “civilised” society. They had to be “educated” and “Christinanised” before that could happen and in the meantime they had to be governed by a form of “tutelage” under their European governors and administrators.

In fact, the very notion of there being an acceptable form of imperialism (or colonialism), i.e.“liberal imperialism”, was a serious contradiction in CL thinking which would have disastrous consequences in the 2nd half of the 20thC when anti-colonial liberation movements began to get underway in earnest. When one looks at the leaders of these anti-colonial independence movements in the post-WW2 period it is apparent that they had studied in universities of the major European capital cities and had learnt, not the free market economic ideas of Mises and Hayek and the liberal political values of JS Mill, but Marxist and Leninist ideas about the central planning of the economy and the dictatorship of the party.

A third example would be the emancipation of gays who would not be allowed to enjoy equal rights under the rule of law until the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

MNR has other reasons to explain why the liberal revolution for emancipation was left unfinished by the end of the 19thC. Like Ebeling he thinks the CLs became complacent with the partial victories they had already achieved and preferred to defend the new status quo from challenges from the rising socialist movement from below and a reconsolidated conservative group from above, instead of pressing on to complete their liberal reform agenda. He also thought that CLs made a number of serious compromises with state power which enabled it to retain considerable power over the economy (such as control over a central bank and the issuing of currency), the armed forces (the retention of a standing army in peacetime, the expansion of the navy in an arms race with other imperial powers), and compulsory tax-payer funded public education (which enabled the state to instill ideas about nationalism and obedience to state in the minds of young people). Rothbard ties these compromises with state power to an underlying ideological cause, which was the gradually abandonment of the more radical defence of individual liberty on the grounds of natural law and natural rights which called for immediate abolition of theses injustices, and its replacement by a much more moderate, gradualist approach to reform based upon the theory of utilitarianism (FNL, pp. 14-15).

For Rothbard, in order to complete the liberal revolution the next “crusades” the CLs should have taken up in the late 19thC were the “separation” of money and the state, the “separation” of education and the state, and the “separation” of guns and the state; thus building upon their already quite successful crusade for the “separation of church and state”.

In spite of the incomplete nature of some of these CL “crusades” they were successful enough to completely transform western societies and lay the groundwork for an extended period of extraordinary prosperity, freedom, and peace which was unprecedented in human history and which we continue to enjoy today. This is in spite of the many setbacks resulting from the more recent period of the growth of government and its regulation of the economy and private life. Useful surveys of this unprecedented transformation of western society can be found in the recent work of Deidre McCloskey on Bouregois Society and the “Great Enrichment” which it made possible to lift 100s of millions of people out of the traditional state of poverty and oppression which they endured for millennia. Accompanying the “Great Enrichment” was what I call the “Great Emancipation” (following McCloskey’s lead in terminology) which is discussed above. On this see the works of Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe: State and Society in the Nineteenth Century (1983) and Jerome Blum, The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (1978).

Bibliography

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Enlarged Edition (The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1992). 1st ed. 1967. Especially chap. III “Power and Liberty: A Theory of Politics,” pp. 55-93.

Bernard Bailyn, “The Central Themes of the American Revolution: An Interpretation,” in S. Kurtz and J. Hutson, eds., Essays on the American Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1973), pp. 26–27.

Jerome Blum, The End of the Old Order in Rural Europe (Princeton University Press, 1978).

Richard M. Ebeling “The Beautiful Philosophy of Liberalism” The Future of Freedom Foundation (July 10, 2018) – online.

Richard Ebeling, For a New Liberalism (American Institute for Economic Research, 2019).

Theodore S. Hamerow, The Birth of a New Europe: State and Society in the Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983).

Jonathan Israel, The Expanding Blaze: How the American Revolution Ignited the World, 1775-1848 (Princeton University Press, 2017).

Jonathan Israel, The Enlightenment That Failed: Ideas, Revolution, and Democratic Defeat, 1748-1830 (Oxford University Press, 2019).

McCloskey’s “Bourgeois trilogy” on bourgeois virtues, dignity, and equality:

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues : Ethics for an Age of Commerce (University of Chicago Press, 2006).

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

- Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (University of Chicago Press, 2016).

Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Challenge (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1959).

Robert R. Palmer, The Age of the Democratic Revolution: The Struggle (Princeton University Press, 1964).

[Pocock] Three British Revolutions: 1641, 1688, 1776. Edited by J.G.A. Pocock (Princeton University Press, 1980).

Murrary N. Rothbard, “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought (Spring 1965, no. 1), pp. 4-22;

Murrary N. Rothbard, “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought (Spring 1965, no. 1), pp. 4-22.

Murray N. Rothbard, For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. Revised edition. (New York: Collier Macmillan, 1978), “Preface. The Libertarian Heritage: The American Revolution and Classical Liberalism,” pp. 1-19. Online at Mises Wire.