| (E)n général on gouverne trop … (mais) comment s’y prendre pour simplifier une machine administrative compliquée où les intérêts privés ont gagné du terrain sur l’intérêt public, comme une gangrène qui s’avance dans un corps humain lorsqu’elle n’est pas repoussée par le principe de vie qui tend à le conserver ?. Pour guérir cette maladie il faut observer comment s’étend la gangrène administrative. Tout homme qui exerce un emploi tend à augmenter l’importance de ses fonctions, soit pour faire preuve d’un zèle qui lui procure de l’avancement, soit pour rendre son emploi plus nécessaire et mieux payé, soit pour exercer plus de pouvoir, augmenter le nombre des personnes obligées d’avoir recours à lui et de solliciter sa bienveillance. Le remède doit suivre une marche contraire et tendre à diminuer les attributions. |

In general we are governed too much … (but) how do we go about reducing the size of a complicated administrative machine where private interests have gained ground over the public interest, like a gangrene which advances in a human body if it is not rejected by the life force which tends to protect it? To cure this disease we have to observe how the administrative gangrene is spread. Every person who is employed (by the state) tends to exaggerate the importance of his functions, whether this is to prove his zeal which will get him promoted, or to make his job (seem) more necessary and (thus) get paid more, or to exercise more power and (thus) increase the number of people who are obliged to come to him to sollicite his goodwill. The cure has to follow an opposite path and has to tend towards reducing the number of (their) duties. |

[J.B. Say “Cours à l’Athénée” (1819), 4th Séance, “Suite des consommations publiques,” Oeuvres, vol. IV, p. 117.]

Note: See also the following:

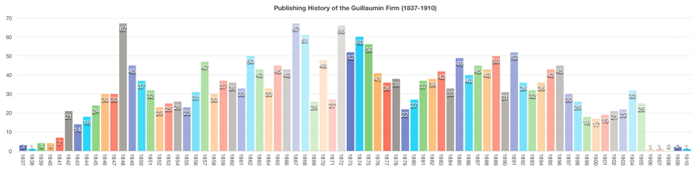

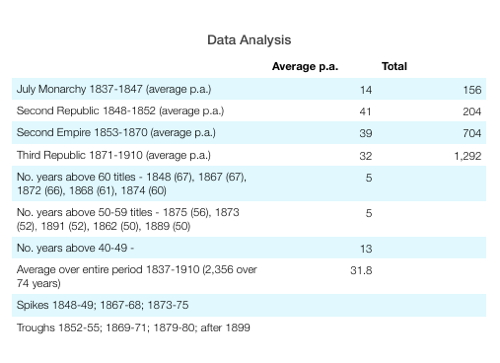

- my blog posts on “A Publishing History of the Guillaumin Firm (1837-1910)” (5 Aug. 2022) here and “The Guillaumin Network and the Paris School of Political Economy” (7 Aug. 2022) here

- my summary webpage on The Paris School

- a brief description of the Guillaumin firm and my list of their publications: “Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-64) and the Guillaumin Publishing Firm (1837-1910)” here

[This post is an excerpt from my longer paper on the Paris School. See this for the full references of works cited.]

Naming the Paris School

The uniqueness and importance of the “Paris School” of political economy has only recently (2006) got the attention it deserves. The late Michel Leter has meticulously reconstructed the membership of its three generations who were active during the nineteenth century. It was a coherent school of thought with a dense network of personal relationships which were mediated through several institutions and organisations based in Paris and which exerted considerable influence in the mid- and late-nineteenth century. This paper will discuss the emergence of the Paris School in the early years of the nineteenth century and its consolidation over three generations of thinkers into a coherent school of economic and social thought some 50 years later. The beginning and end points for the discussion are 1803, when Jean-Baptiste Say published the first edition of his Traité d’économe politique and the appearance of Guillaumin’s Dictionaire de l’économie politique (1852-53) some fifty years later.

Before Leter, the Austrian economist Murray Rothbard in his history of economic thought (1995) gave due recognition to what he called “the French Smithians” led by J.B. Say which gradually evolved into “the French laissez-faire school” with Frédéric Bastiat as “the central figure.” At the time, the Parisian economists were content to call themselves simply “les Économistes” just as the Physiocrats had done the previous century. Hence, the title of their journal founded in 1841 by Guillaumin, “Journal des économistes” (Journal of THE Economists). It only gradually occurred to some of them to call themselves a particular school of thought as the 1840s wore on, when a number of them came to appreciate the “Frenchness” of their way of looking at economics, as opposed to the English classical school founded by Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo, and their followers in France. This was at first implied with the inclusion of a preponderance of French authors in the 15 volume Collection des Principaux Économistes edited by Eugène Daire beginning in 1840 (of the 15 volumes 10 were by French authors and 5 by the Anglo-Scottish authors Smith, Malthus, Ricardo). In his introductory essay to the volume with works by the late 17th century economist Boisguilbert (1843) Daire claimed that the economists of his day were the most recent “links in the chain of knowledge” which began with Boisguilbert and then moved on to Quesnay, Smith, JBS, Malthus, Ricardo, and finally Rossi. Making French economists like Boisguilbert, Quesnay, J.-B. Say, and Rossi coequals of Smith, Malthus, and Ricardo is a claim no member of the English classical school would ever have made.

The realisation that the Paris economists were not just an offshoot of the Anglo-Scottish school, but something sui generis, became explicit when a small group began to break away from English orthodox thinking on the role of the state (Molinari), central banking (Coquelin), Smithian labour theory of value (Bastiat), Ricardian rent theory (Bastiat), and Malthusian population theory (Bastiat and Fontenay). Bastiat, for instance, came to realise he owed more of his intellectual development to another school of thought, “cette école éminemment française” (this eminently French school), of Say, Destutt de Tracy, Charles Comte, and especially Charles Dunoyer (whom he had read as a youth) than to “l’école de Malthus et de Ricardo” (the school of Malthus and Ricardo), or what his friend Roger de Fontenay rather dismissively called “cette école anglaise” (this English school).

Although Bastiat did not go on to form a school of his own, as Fontenay had hoped, he was recognised by later members of the Paris School as one of its leading members for his contributions to both economic reform and theory. When one of the members of the third generation of the Paris School, Frédéric Passy (1822-1912), was asked by the Swiss Christian Society of Social Economy in 1890 to give a lecture on what they called “L’École de la Liberté” (the School of Liberty) as part of a month long program of lectures reviewing the state of political economy in the French speaking world at the end of the nineteenth century what he gave was, in effect, a kind of requiem for the “Paris School” which he defended before a hostile audience of socialists and other interventionists. Passy acknowledged the importance of Bastiat in his conclusion by calling him “the most brilliant and purest representative of the doctrine of liberty.”

Various Streams of Economic Thought and their History

The Paris School was by no means monolithic in its thinking and had to contend with several sub-currents which flowed within it, as well as countering criticism of its ideas from competing schools outside. Within, it was based upon two different intellectual foundations. The older, home-grown thread which came from the Franco-Physiocratic school or what might be termed “the precursors” of Pierre de Boisguilbert (1646-1714), Richard Cantillon (1680-1734), François Quesnay (1694-1774), Étienne Bonnot de Condillac (1714-80), and Turgot (1727-81). Equally important was the Anglo-Scottish thread of Adam Smith (1723-1790), Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), Thomas Malthus (1766-1858), and David Ricardo (1772-1823).

Members of the Paris School, with the financial backing of Guillaumin, spent a lot of time rediscovering and promoting their diverse intellectual roots as the work of Adolphe Blanqui (1798–1854) and Eugène Daire (1798–1847) in our period reveal. And it would be done again fifty years later by Maurice Block. One of the first three books ever published by the Guillaumin firm when it opened in 1837 was Blanqui’s Histoire d’économie politique en Europe (1837) which was part history of economic thought and part economic history of Europe which went back to the ancient Greeks. It remained in print as long as Guillaumin lived, going through four editions. Guillaumin must have also invested heavily in one of the most ambitious publishing projects of the firm which saw in only its fourth year of operation the publication of the first volume of what would become 16 very large volumes called the Collection des Principaux Économistes under the editorship of Daire. It brought together in print the two threads mentioned above in a dramatic and striking visual way – 16 large volumes, with a total of 11,000 pages of classic texts and new notes by the editors, which could be purchased as a hardcover set for 200 fr. Guillaumin would do the same in its next big publishing project, the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852) which would also have the history of economic thought as a core component.

It is interesting to speculate why they placed so much importance on their intellectual heritage. Several reasons come to mind: they might want to show that free market ideas were not an “English import” but had deep roots in France going back to the 17th century; that there was a long tradition of thinking about economic theory and that this body of thought was a “science” like any other; and that their intellectual forebears had overcome political and other obstacles (the persecution of Boisguilbert by Louis XIV comes to mind) just as they were trying to do in their own time. However, I believe the major reason is that they wanted to show, as Daire eloquently put it in his remark about the “links in the chain of knowledge” that this French tradition continued up to their own day. Yet, how these two intellectual foundations could be reconciled with each other was a constant source of debate during our period. The thread of Boisguilbert-Turgot-Condillac-Say sometimes clashed with the so-called “classical” thread of Smith-Malthus-Ricardo, especially the latter’s notions of value, rent, and population, as the revisionist work of Bastiat in the mid-1840s would show.

Upon these foundations the early members of the Paris School such as Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832), Destutt de Tracy (1734-1836), and Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862), began doing their own innovative work on the entrepreneur, the nature of markets, and the new “industrialist” society which was emerging before their eyes. By the 1840s the school had matured into a well-organised group with its own journals, associations, a publishing firm, and contacts which extended well into the broader political and intellectual life of Paris. The main figures at this time were the publisher Gilbert Guillaumin (1801-1864) whose firm provided a locus for the school’s activities, Adolphe Blanqui (1798-1854), Eugène Daire (1798-1847), Charles Coquelin (1802-1852), and Michel Chevalier (1806-1879). Its main focus was on ending the policy of trade protection and then countering the rise of socialism in the 1848 Revolution.

The school was also developing its own smaller group of “young Turks” (not all of whom were young in age) within it who began pushing the boundaries of the school into new and more radical directions until the outbreak of the February Revolution 1848 forced the entire school to change direction. This latter group of radicals and anti-statists consisted of Charles Coquelin (1802-1852), Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912), and Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850), but their work was cut short through a combination of premature deaths and self-imposed exile from Paris following the rise to power of Louis Napoléon, soon to declare himself Napoléon III.

Outside the Paris School there were several schools of thought which were very hostile to their ideas and the policies based upon those ideas. This included an “Imperialist or Nationalist school” which supported protectionism and state support for favoured industries (Saint-Chamans, Ferrier, Lebastier, Lestisboudois); a “Social Reformist school”, also known as the “Sentimentalist” school, which wanted the state to take a more active role in addressing “the social problem” of poverty and poor living conditions in the factories – this had a religious Catholic version (social Catholicism) (Villeneuve-Bargemont and later Le Play), a Sismondian version (Sismondi), and a liberal version (Lammenais, Montalembert); a “Socialist school” which had various diverse elements within it (Fourier, Blanc, Considerant, Proudhon); and a “Saint-Simonian school” which sought technocratic, state directed reforms and public works – with a free trade version (Chevalier) and a Napoleonic version (Louis Napoléon).

It should also be noted that, at the very end of our period, another school of thought began to emerge which had its roots partly at least in Paris, namely the thought of Karl Marx. He spent time in Paris in the mid and late 1840s, which was the heyday of the Paris School, where he met Friedrich Engels, researched and wrote The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts (1844), and distributed the first copies of “The Communist Manifesto” (1848). Marx had minimal contact with members of the Paris School (discussed below) and his ideas were not known to the latter at this time.

What the Paris School believed in and what they opposed

In spite of differences between individual members of the Paris School there were some things they all by and large agreed upon. These included in general philosophical terms, a belief in individual liberty in both its political and economic dimensions, the right to self ownership and the right to own the things that the self was able to create or produce, and the right to trade one’s justly owned property and services with others both domestically and internationally (free trade).

More specifically, when it came to political liberty they believed in freedom speech, freedom of religion, freedom of association, representative government and a broader franchise, and the rule of law. Concerning economic liberty, they believed in private property, free markets, free trade, sound money, and low and more equally distributed taxes.

They also largely agreed on what they opposed. These included the following: protectionism and subsidies to industry, a state monopoly in education, state funding of churches, censorship, slavery, colonialism, conscription for the standing army, war, and socialism.

In spite of considerable agreement on many fundamental economic and political ideas, the school was divided over several key issues which they were never able to resolve, namely, republicanism vs. a constitutional monarchy, the number of public goods the government should provide, free banking, the cause of business cycles, and the extent of “tutelage” the government should provide for the poor and the ignorant and uneducated.

The Three Generations of the Paris School

We can identify three generations of individuals who made up the Paris School, grouped according to when they were born and when they were most active. The first generation of 13 individuals were born under the Old Regime and were active in the Empire (1803-1815) and the Restoration (1815-1830) when the first indications that a coherent school of thought began to emerge. It was in this early stage that we can see the first important productive period between 1815 and 1825 when a number of important books were published and innovative ideas were first introduced. The second generation of 26 individuals were born during the French Revolution and the First Empire and were active during the July Monarchy (1830-1848) and Second Republic (1848-1852). The 1830s was a difficult time for the school as it tried to rebuild itself after a number of deaths depleted their ranks, by working within the newly reconstituted Institute (1832) and creating their own organisations from scratch like the Guillaumin publishing form (1837). The third generation of 23 individuals were born during the Restoration period and were active in the late July Monarchy and later in the century. The period from 1842 to 1852 saw the flowering or “take-off” of the school into a well organised, active, and productive group of very like-minded individuals. This decade was the second important period for the number of important books and new ideas which appeared by members of the school, culminating with the publication of the Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852-53). The “flowering” of the Paris school lasted until 1877 when a restructuring of the state university system erected serious impediments to the further expansion of the school, after which it went into a decline which lasted until the death of one of its last major figures, Yves Guyot (1843-1928).