Most economists and social theorists, if they have ever heard of him, dismiss Frédéric Bastiat as a light-weight theorist. Joseph Schumpeter summed up the consensus view in 1954 describing him as “no theorist at all” with the very witty but false put down, that he was a clever journalist who got out of his depth in the swimming pool of theory and drowned.

In this paper I conclude that Bastiat was in fact a theorist of considerable skill and originality who had conceived of a multi-volume work on social and economic theory the outline of which I have been able to reconstruct from his scattered remarks:

- volume one would be a general theory of how human society in general functions, called Social Harmonies;

- volume two would be his economic theory, called Economic Harmonies; and

- the final volume or volumes would deal with disrupting factors or “disharmonies” and would be called A History and Theory of Plunder.

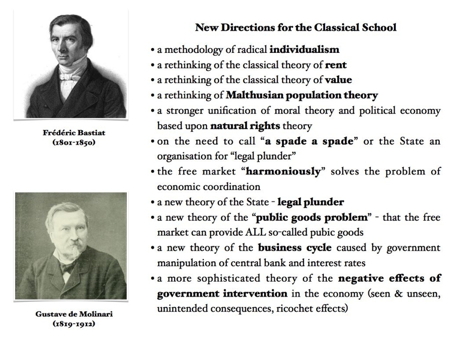

Not having time to complete this project because of his rapidly failing health (he died of throat cancer at the age of 49), Bastiat focused the time remaining to him to working on the Economic Harmonies. I have identified 16 elements of his economic thought which I believe demonstrate his sophistication and originality as an economic theorist. These include:

- an individualist methodology of the social sciences (in particular his invention of “Crusoe economics” to explore the logic of human action),

- an early form of subjective value theory,

- the interdependence or interconnectedness of all economic activity,

- the transmission of economic information through the economy,

- the idea of opportunity cost,

- the idea of the “ricochet effect” or multiplier, and

- his Public Choice-like theory of politics and “place-seeking”, among others.

Copies of the paper: