Further research into the origins and meaning of the national anthem, “Advance Australia Fair” (henceforth AAF), is revealing some interesting facts.

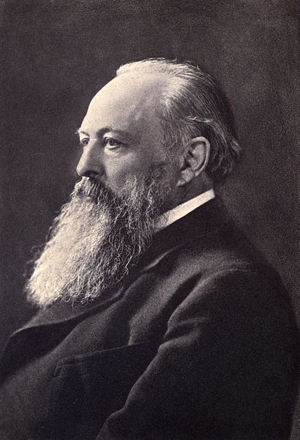

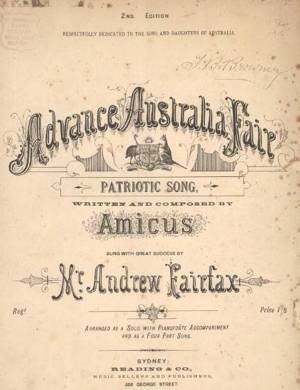

The Author: Peter Dodds McCormick (c. 1834-1916)

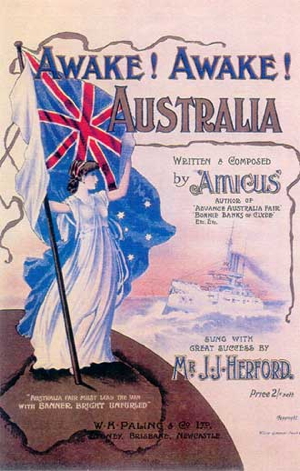

The author Peter Dodds McCormick (c. 1834-1916) (his nom de plume was “Amicus” – so shouldn’t this be “nom de tune”?) was a Scottish immigrant who came to Australia in 1855 and worked as a joiner / carpenter, then in a number of high schools in Sydney ( St. Mary’s National School and Plunkett St. Public School), and was active in the Presbyterian church and choirs (as music director of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of NSW), hence his interest in writing patriotic songs for the colony of NSW and then later the Commonwealth of Australia. He may have written around 30 patriotic and Scottish songs during his life.

Jim Fletcher in the NDB describes McCormick as “ultra-Scottish and ultra-patriotic” who liked to organise massed choirs such as “the 10,000 children and 1000 teachers at the 1880 Robert Raikes Sunday school centenary demonstration, and 15,000 schoolchildren at the laying of the foundation stone of Queen Victoria’s statue.” 1

Graeme Skinner tells us that AAF was “first sung at the St Andrew’s Day concert of the Sydney Highland Society on 30 November 1878.” McCormick later made some revisions to the words and this revised version was sung by a choir of 10,000 at the inauguration of the Commonwealth which was held in Centennial Park, in Sydney. The tune was also played by “massed bands” at the naming of the Federal capital celebrations in Canberra (Fletcher).2

A statue of McCormick in the grounds of The Scots Church in Margaret Street, Sydney [from the “Urban Ambler”].

The Difficult Birth of a National Anthem

AAF only became Australia’s official national anthem after a tortuous political process. A new anthem was sought by Gough Whitlam’s Labour Party government in 1972 as part of its “It’s Time” campaign to remake Australia along more progressive lines. The Australia Council for the Arts took submissions (receiving about 1400) and recommended a short list of three to go to a referendum – Banjo Paterson’s folk song “Waltzing Matilda” (1895), the South Australian poet Caroline Carleton’s “Song for Australia” (1859), and McCormick’s “Advance Australia Fair” (1878). A referendum was held in 1974 and AAF won with 51.4% of the vote.

The next government led by Malcolm Fraser of the Liberal Party was staunchly monarchist and so ditched the results of the referendum and returned to “God Save the Queen” in 1976. However, opposition to this old anthem persisted and another poll was held in 1977, this time including the monarchist anthem as one of the choices, with a repetition of the result from the earlier poll. The figures were:3

1977 poll (6,767,000):

Advance Australia Fair – 2 940 854 (43%)

Waltzing Matilda – 1 918 206 (28%)

God Save the Queen – 1 257 341 (18%)

Song of Australia – 652 858 (10%)

After Preferences (6,768,000):

Advance Australia Fair – 4 415 642 (65%)

Waltzing Matilda – 2 353 617 (35%)

After a considerable delay the Governor General of Australia, Sir Ninian Steven, officially proclaimed “Advance Australia Fair” as the national anthem on 19 April 1984.

Rewriting the Contested Lyrics

The cultural values of the Anglo-Scottish community in Australia in the late 19thC are clearly visible in the two songs I have come across, AAF and “Awake Australia” (see my earlier post on this, and have been pointed out by critics many times. These include:

- the assumption that Australia was open and unoccupied territory which was there for the taking (the “Crown” permitting of course, since it owned it all as a resulting Cook’s claiming in 1770). So much for the Lockean principle of ownership stemming from the first comer “mixing one’s labour” with the land and making it “theirs”

- that the land was the preserve of the immigrants from England, Scotland (like McCormick), and Ireland, and no others (as no one else is mentioned)

- the pro-British Empire sentiments, such as boasting that “Britannia rules the waves” and the glorification of martial values – the new Aussies would “rouse to arms like sires of yore” and that Britain’s “sons” still kept a “British soul” and would defend their “native strand” (i.e. their sandy beaches) from any foreign foes (Russian, French, Chinese?)

- the meaning of the word “fair” in the refrain. Did it mean “fair” as in “reasonable” or “fair” as in fair-skinned? It is open to interpretation.

The words to AAF have been changed many times over the decades in order to suit the changing needs of its listeners (and presumably the singers as well) to the point where it has become very politicized.

Firstly, by McCormick himself on the eve of Federation in 1901. For example he mentions the “Commonwealth”.

Then by the selection committee when the Labor government was looking for a replacement for “God Save the Queen”. When the song was proclaimed as the “national” anthem the following changes had been made to McCormick’s verse:

- “Australia’s sons, let us rejoice” was changed to “Australians all, let us rejoice”

- “To make our youthful Commonwealth” was changed to “To make this Commonwealth of ours”

- “For loyal sons beyond the seas” was changed to “For those who’ve come across the sea”

The original five verses were also cut down to only two (only the 1st and 3rd verses were kept). Those verses cut were no. 2 which was very pro-conquest and Empire; no. 4 which explicitly mentioned only Brits, Scots, and Irish as settlers; and no. 5 which was bellicose and male-oriented. The complete song is as follows with the kept verses 1 and 3 in bold:

Australians all let us rejoice,

For we are young and free;

We’ve golden soil and wealth for toil,

Our home is girt by sea;

Our land abounds in Nature’s gifts

Of beauty rich and rare;

In history’s page, let every stage

Advance Australia fair!

In joyful strains then let us sing,

“Advance Australia fair!”When gallant Cook from Albion sail’d,

To trace wide oceans o’er,

True British courage bore him on,

Till he landed on our shore.

Then here he raised Old England’s flag,

The standard of the brave;

With all her faults we love her still,

“Brittannia rules the wave!”

In joyful strains then let us sing

“Advance Australia fair!”Beneath our radiant Southern Cross,

We’ll toil with hearts and hands;

To make this Commonwealth of ours

Renowned of all the lands;

For those who’ve come across the seas

We’ve boundless plains to share;

With courage let us all combine

To advance Australia fair.

In joyful strains then let us sing

“Advance Australia fair!”While other nations of the globe

Behold us from afar,

We’ll rise to high renown and shine

Like our glorious southern star;

From England, Scotia, Erin’s Isle,

Who come our lot to share,

Let all combine with heart and hand

To advance Australia fair!

In joyful strains then let us sing

“Advance Australia fair!”Shou’d foreign foe e’er sight our coast,

Or dare a foot to land,

We’ll rouse to arms like sires of yore

To guard our native strand;

Brittannia then shall surely know,

Beyond wide ocean’s roll,

Her sons in fair Australia’s land

Still keep a British soul.

In joyful strains the let us sing

“Advance Australia fair”

The most recent change was made by the current Prime Minister, Scott Morrisson, who surreptitiously one weekend in late Dec. 2020, when everybody was on holidays or preoccupied by Christmas and New Year, changed the phrase “for we are young and free” to “for we are one and free.” This is problematical for several reasons. One is that Australia is definitely not “one” on the issue as the controversy about the words of the anthem and the date of our “national day” is hotly disputed. Second, aboriginal groups rightly state that their culture is not “young” as they are descendants of one of the oldest cultures on the planet. Only the Constitution of the nation state of Australia is “young”, at least in comparison. Thirdly, as a libertarian I do not regard Australia as “free” given its large welfare state, high rates taxation, massive bureaucratic regulation of our lives, and a history of high tariffs and government subsidies to privileged industries. In response to this, I have written my own version of the first verse of AAF which is included below,

Morrison’s act also raises the following question in my mind: Is the power to unilaterally change the words of the “national” anthem one of the enumerated powers of the PM under the Constitution? I think not.

Others have rewritten the anthem in an attempt to remove some of its more objectionable aspects. Jens Korff at “Creative Spirits” discusses and quotes a number of alternative versions of the anthem.4

Judith Durham (once a member of Australian pop group “The Seekers”) with the help of Kutcha Edwards has written a very good substitute which I include here.

Australia, celebrate as one, with peace and harmony.

Our precious water, soil and sun, grant life for you and me.

Our land abounds in nature’s gifts to love, respect and share,

And honouring the Dreaming, advance Australia fair.

With joyful hearts then let us sing, advance Australia fair.Australia, let us stand as one, upon this sacred land.

A new day dawns, we’re moving on to trust and understand.

Combine our ancient history and cultures everywhere,

To bond together for all time, advance Australia fair.

With joyful hearts then let us sing, advance Australia fair.Australia, let us strive as one, to work with willing hands.

Our Southern Cross will guide us on, as friends with other lands.

While we embrace tomorrow’s world with courage, truth and care,

And all our actions prove the words, advance Australia fair,

With joyful hearts then let us sing, advance Australia fair.And when this special land of ours is in our children’s care,

From shore to shore forever more, advance Australia fair.

With joyful hearts then let us sing, advance … Australia … fair.

Peter Vickery, a former Victorian Supreme Court judge and founder of “Recognition in Anthem”, has written in 2019 two new verses which he has entitled “Our People” and “Our Values”. Our People goes as follows:

For sixty thousand years and more

First peoples of this land

Sustained by Country, Dreaming told

By song and artist’s hand.

Unite our cultures from afar

In peace with those first here

To walk together on this soil

Respect for all grows there.

From everywhere on Earth we sing, Advance Australia Fair.

I have even come across a parody, “Advancing Australian Fires”, written by “Mick” at the height of the bushfires in the summer of 2019/20:5

Australians why do we rejoice

While we are all on fire?

Our leader is incompetent,

Let’s throw him on the pyre.For monied hands across the seas

We’ve pillaged land and sky.

Now we will reap what we have sown –

We’ll watch the nation fry.With no remorse let’s go all in,

Come strip Australia bare.

There have been two attempts to “Christianise” the song as the following examples show; The first was written by Dr Robin Lorimer Sharwood, fourth Warden of Trinity College in The University of Melbourne, and is apparently used within St Paul’s Cathedral Melbourne:6

O God, who made this ancient land,

And set it round with sea,

Sustain us all who dwell herein,

One people strong and free.

Grant we may guard its generous gifts,

Its beauty rich and rare.

In your great name, may we proclaim,

`Advance, Australia fair!’

With thankful hearts then let us sing,

`Advance Australia, fair!’Your star-bright Cross aslant our skies

Gives promise sure and true

That we may know this land of ours

A nation blessed by You.

May all who come within its bounds

Its peace and plenty share,

And grant that we may prayerfully

Advance Australia fair.

With thankful hearts then let us sing,

`Advance, Australia fair!’

There is another Christian verse of unknown origin:

With Christ our head and cornerstone,

We’ll build our nation’s might;

Whose way and truth and light alone

Can guide our path aright;

Our lives a sacrifice of love,

Reflect our Master’s care

With faces turned to heaven above

Advance Australia Fair!

In joyful strains then let us sing,

Advance Australia Fair!

In imitation of the New Zealanders who have an English and a Maori version of their anthem “God Defend New Zealand” (1876), someone in the Australian rugby fraternity wrote a verse in the Eora language which was sung at the Australia vs Argentina Tri Nations match last year. The words are as follows:7

Australiagal ya’nga yabun

Eora budgeri

Yarragal Bamal Yarrabuni

Ngurra garrigarrang

Nura mari guwing bayabuba

Diara-murrahmah-coing

Guwugu yago ngabay burrabagur

Yirribana Australiagal

Garraburra ngayiri yabun

Yirribana Australiagal

In order to get the meter right for the purpose of singing it to the tune of “Advance Australia Fair” the Eora words are very terse and the translation provided by the unnamed author is not very coherent or understandable to English ears.

Australian(s) do sing

People Good

Yellow Earth (ground) do not fatigue yourself

Country many (a very large number) sunrise

The sun setting red

Presently today future event tomorrow

This way Australian(s)

To dance bring sing

This way Australian(s)

It certainly leaves out the controversial parts of the English language version which in my view makes it a rewrite of the anthem not a true translation. Since the Eora language has not had any native speakers for a very long time it has had to be reconstructed by linguists from notebooks made by some of the observations made by science officers in the First Fleet (e.g. David Collins and Lt. William Dawes) .8

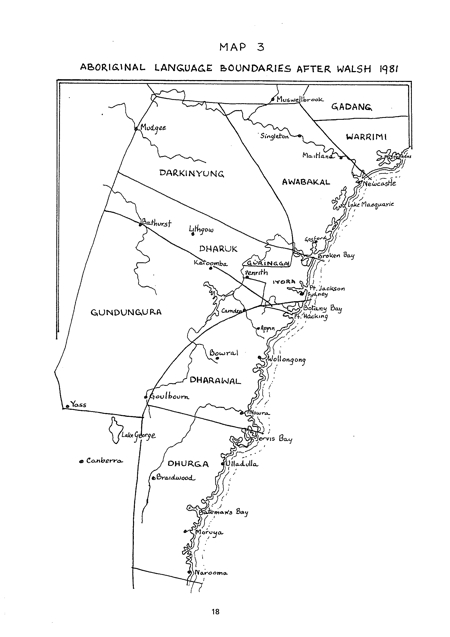

A further problem which comes to mind is the selection of only one aboriginal language for the translation. One could argue that Eora was the language of the clans which lived in the Sydney region at the time of the arrival of the First Fleet (estimated to be about 30 in number), but this became a “dead” language when the population was either wiped out by disease or “assimilated” into the broader community by the late 19thC. Why wasn’t a “living” aboriginal language chosen, one with perhaps the most native speakers alive today?

Map of Aboriginal languages in the Sydney area.

Since there are now so many different version to choose from, I thought I would add my own “libertarian” version of the national anthem to the mix.

Australians let’s all feel remorse

For we were strong and free;

Our golden soil and wealth from toil

Is taxed by tyranny.

Our land abounds with harmful laws

So we must take a vow;

For history’s sake, our children’s fate,

Let’s free Australia now!

With angry voice then let us shout,

Let’s free Australia now!

- Jim Fletcher, “McCormick, Peter Dodds (1834–1916)”, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 30 January 2021. [↩]

- Graeme Skinner, “McCormick, Peter” The Dictionary of Sydney (2008). [↩]

- Source: The Australian National Flag Association – “National Symbols – National Anthem”. [↩]

- Source: Jens Korff, “National anthem: Advanced, Aboriginal & Fair?” (1 Jan. 2021). [↩]

- Source: “Am I Right” website Advancing Australian Fires, Parody Song Lyrics of Peter Dodds McCormick, “Advance Australia Fair”. [↩]

- Source: David C. Leslie’s article. [↩]

- Source: NSW Government website, “Australia Day in NSW”. [↩]

- See the work by Jakelin Troy, The Sydney Language (Canberra 1993). [↩]