Updated: 25 Apr. 2022

[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

[See a larger version of this image.]

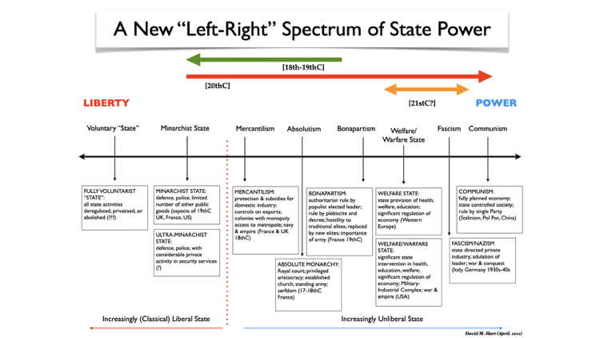

A key factor in distinguishing the differences between the various strains of liberalism is their attitude towards the state (not just between liberalism and other political philosophies like socialism, communism, fascism, etc – see my post on “The Spectrum of State Power: or a New Way of Looking at the Political Spectrum” (10 Aug., 2021) online.

Radical Liberals

For radical liberals and libertarians the state was thought to be a threat to, or even an enemy of, liberty since it was “the organisation of the political means of acquiring wealth” (Franz Oppenheimer) . Historically, this had certainly been the case where the state had been controlled by particular groups who used it to get benefits and privileges at the expence of ordinary citizens and tax-payers (slave owners, aristocratic landowners, favoured and privileged manufacturers, bankers who lent money to the state). In the present (i.e. the 18th and 19thC), even with written constitutions designed to limit the power of the state to very specific activities, and an electorate which had been opened up to previously excluded and exploited classes, the state was still an entity with a monopoly on the use of coercion. Its very existence meant that it was a tool which could be seized by vested interests and classes and used to benefit themselves and which could be exercised behind the legal shield of constitutional and legal propriety. In their view, plunder was still plunder, even it had been approved by a democratically elected body and conducted along proper constitutional and legal procedures. [See Bastiat’s notion of “la spoliation légale” (legal plunder).]

Whether or not the power of the state would be used that way was a matter for conjecture in the late 18th and 19th centuries as attempts to strictly limit the power of the state had never been tried before. That is why the American experiment in drafting a Constitution and Bill of Rights was so important for CLs of the period. If the Americans could succeed in permanently reducing and limiting the power of state and keeping it limited, then the case for limited government would be made.

However, even when this experiment was in its early days, there were sceptics who thought that, although a noble one, this experiment would eventually fail because the state provided too attractive a tool for unscrupulous “rent seekers” (I prefer the term “privilege seekers”) to use for their own benefit, as well as creating a vested interest to maintain or expand the power of state by professional politicians and bureaucrats (the “public choice” argument). This fear was expressed by the so-called “anti-federalists” (who were actually the true “federalists” not Madison and Hamilton who believed in a strong central state) in the 1780s , and then even more forcefully by radical liberals like Herbert Spencer in England in the 1870s and 1880s and Bastiat and Molinari in France in the late 1840s and later.

The radical liberal and libertarian hostility towards the state, on the grounds that its initiation of the use of coercion in everything it does is immoral and unjust, was summed up by Rothbard. In an essay in 1977 he asked the question of his readers, “Do you hate the state?” His answer was “There runs through For a New Liberty (and most of the rest of my work as well) a deep and pervasive hatred of the State and all of its works, based on the conviction that the State is the enemy of mankind. “ “Do you hate the state?”, Libertarian Forum (Vol. 10, No. 7, July 1977) online .

Moderate Liberals

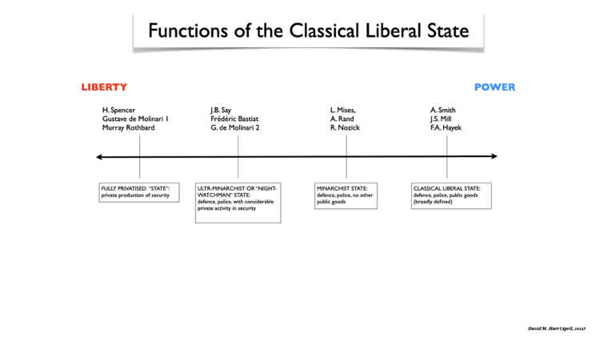

More optimistic were the moderate liberals who thought the state could be limited to a small number of very specific and “ennumerated” powers (to use the terminology of the American constitution). The economic argument for a limited state was made by Adam Smith who provided the “classic” formulation of this view, that the state should be limited to providing police, courts, national defence, some minimal welfare for the poor, and some public works (roads, post office, and possibly education).

By protecting property rights and upholding contracts the limited state provided the general legal framework for markets to operate. Once this had been achieved the state should not interfere in the private activities of men and women going about their lives and conducting their business activities. The assumption behind this was that an educated public would make sure the state did not step outside its proper bounds and that an independent judiciary and court system would ensure the protection of liberty and property rights, as well as a means by which citizens could protect their liberties by suing the state and its officials in the independent courts if they did not carry out their proper duties.

In other words, the moderate liberal position could be summed up by saying that, even thought he state could at times be dangerous and a threat to liberty (hence one had to be very wary), it was a “necessary evil” which was required to protect the “ liberal order.”

One of these assumptions, that an educated public would behave properly by respecting the rights of others and would make sure the state did not step outside its proper bounds (via the pressure of public opinion and frequent elections), led to the conclusion that the state should provide a minimal of free, state funded education to ensure that this happened. The debate about state funded, compulsory education tore apart the classical liberal movement during the 19thC. For example, in England, one of the leading radical liberals, Richard Cobden, was a strong supporter of state-funded education, whereas Herbert Spencer was not, as he believed it provided a “foot in the door” for the state to tax and regulate and compel the population (which might serve as a model for other attempts to “improve the lot of the people, something which the “new” liberals in the late 19thC certainly did), as well as a means for the state to indoctrinate children in pro-state beliefs. In France, liberals and liberal conservatives (like Guizot) used state funded education as a means to break the control the Catholic Church had over education and to propagate secular and republican political ideas. Even a very radical liberal like Gustave de Molinari, who was the first advocate and theorist of what later became known as “anarcho-capitalism”, believed that education should be made compulsory for all children but that it should not be provided or funded by the state. Even in 19thC America, where the state was much more limited than practically anywhere else, education was provided by the state (via local property taxes), albeit at a a very decentralised, local level. Even here, the state education system was used as a tool in the late 19thC to “Americanise” and “republicanise” immigrants from central and eastern Europe who tended to be Catholic and have other “bad” European habits and beliefs (such as drinking wine and beer) which were thought to be harmful to white, Protestant America.

“New” Liberals

For the growing number of “new” liberals in the late 19thC the state provision of education was just the first of many similar “services” the state should be providing to improve the lives of its citizens in a “positive” rather than “negative” way. The same reasons used by supporters of state education were used to justify the state provision of unemployment insurance, the regulation of factories and other forms of labour, public hygiene, as well as local utilities such as street lighting, gas supplies, and public transport. The Fabian socialists who were also emerging at this time called this activity by the state “municipal socialism”, and it was something that also strongly appealed to the “new” liberals.

In general, the new liberals rejected the great suspicion felt by radical and many moderate liberals of state action. They preferred to see the state as the protector and provider of greater liberty and opportunity, as a friend and benefactor (like a parent, or father) of the ordinary person, and not as their enemy.

In Australia, where the state had always played a greater role in people’s lives from the beginning of the penal colony run by the military (creating a kind of “military socialism”), by the late 19thC there was a opportunity to take the idea of “municipal socialism” even further, to create what was called at the time “colonial socialism.” The state (in the name the Crown) was the largest landowner in the country, infrastructure projects like ports and railways were thought to be impossible to finance via private capital and run by private companies (as they were done in the US) so it was argued that the colonial states had to step in to ensure economic development, and tariff protection for domestic industry was also thought to be essential (except in the state of NSW which was largely free trade). Even most Australian “liberals” were in favour of these measures, except for a handful of radical liberals like William Hearn at the University of Melbourne (a follower of the economic thought of Frédéric Bastiat) and the NSW MP Bruce Smith (who was a follower of Herbert Spencer). Thus, by the time of Federation in 1901 there was a broad consensus among the socialists in the Labor Party and the “liberals” in the Protectionist Party and the Free Trade Party about the need for a large role for the state in the new Commonwealth of Australia.

Radical liberalism was practically non-existent in Australia because of its later political development. Radical liberals in Britain had drawn upon the natural rights tradition as expressed in the writings of the Levellers (1640s), John Locke (16890s), and the Commonwealthmen (1720s and 1730s), which had also spread to the north American colonies on the eve of the Revolution, and were the guiding principles of the “classical liberalism” which emerged there (although not called that at the time). [See Rothbard’s chapter on “The American Revolution and Classical Liberalism” from For a New Liberty (1974) online at Mises Wire.] When Australians were thinking about independent colonial government in the 1850s this radical strain of liberalism was dying out in Britain (except for a few individuals such as Thomas Hodgskin – see his The Natural and Artificial Right to Property Contrasted (1832)) and was rapidly being replaced by the less radical utilitarian strain of liberalism whose main theorists were Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. One might say that if there were a guiding light for Australian liberalism it was Bentham and not Locke who held the torch aloft. Thus on the eve of Federation the ideas of JS Mill (moderate and rather weak as they were) and those of Thomas Green (a staunch advocate of the “new” much more interventionist strain of liberalism) had the greatest impact on the development of Australian liberalism. [See David Llewellyn , AUSTRALIA FELIX: Jeremy Bentham and Australian colonial democracy (PhD. thesis, University of Melbourne, July 2016).]

A sure indicator of the “moderate” even “compromised” nature of Australian liberalism was the widespread support for protectionism in the colonies and then for the first 70 odd years of the new Commonwealth. Belief in free trade was an absolute precondition for being a liberal (even a moderate liberal) at the time of Cobden and Gladstone. Not so in Australia. [Side note: The alliance between the Australian Liberal Party and the Country Party defended the policy of protection until it was gradually overturned ironically enough by the Labor Party under Hawke and Keating.]