The Dutch legal theorist Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) published the first edition of his important book on the Laws of War and Peace in 1625 while he was in exile in Paris. His second edition of 1670 was published in Amsterdam and came with two etchings, one of himself and another which was an allegorical etching of Justice, War, and Peace (or Bounty) which served as the frontispiece of the book.

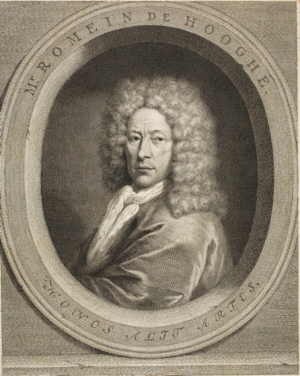

The engraver was Romeyn de Hooghe (1645 – 1708) who was a Dutch painter and engraver who made political prints in support King William of Orange (1650-1702). See Romeyn de Hooghe – Wikipedia.

Romeyn de Hooghe (1645 – 1708)

The portrait of Grotius:

See the larger version 1781×3042 px

The allegorical etching is a very interesting visual summary of Grotius’ book. A printed summary of his ideas can be found in Grotius’ “Prolegomena” to his book which I have made available in HTML.

That body of law, however, which is concerned with the mutual relations among states or rulers of states, whether derived from nature, or established by divine ordinances, or having its origin in custom and tacit agreement, few have touched upon. Up to the present time no one has treated it in a comprehensive and systematic manner ; yet the welfare of mankind demands that this task be accomplished. …

Such a work is all the more necessary because in our day, as in former times, there is no lack of men who view this branch of law with contempt as having no reality outside of an empty name. … Of like implication is the statement that for those whom fortune favours might makes right, and that the administration of a state cannot be carried on without injustice. …

Furthermore, the controversies which arise between peoples or kings generally have Mars as their arbiter. That war is irreconcilable with all law is a view held not alone by the ignorant populace ; expressions are often let slip by well-informed and thoughtful men which lend countenance to such a view. Nothing is more common than the assertion of antagonism between law and arms. …

Since our discussion concerning law will have been undertaken in vain if there is no law, in order to open the way for a favourable reception of our work and at the same time to fortify it against attacks, this very serious error must be briefly refuted. …

Man is, to be sure, an animal, but an animal of a superior kind, much farther removed from all other animals than the different kinds of animals are from one another; evidence on this point may be found in the many traits peculiar to the human species. But among the traits characteristic of man is an impelling desire for society, that is, for the social life—not of any and every sort, but peaceful, and organized according to the measure of his intelligence, with those who are of his own kind; this social trend the Stoics called ‘ sociableness’. …

This maintenance of the social order, which we have roughly sketched, and which is consonant with human intelligence, is the source of law properly so called. To this sphere of law belong the abstaining from that which is another’s, the restoration to another of anything of his which we may have, together with any gain which we may have received from it; the obligation to fulfil promises, the making good of a loss incurred through our fault, and the inflicting of penalties upon men according to their deserts. …

From this signification of the word law there has flowed another and more extended meaning. Since over other animals man has the advantage of possessing not only a strong bent towards social life, of which we have spoken, but also a power of discrimination which enables him to [ix] decide what things are agreeable or harmful (as to both things present and things to come), and what can lead to either alternative: in such things it is meet for the nature of man, within the limitations of human intelligence, to follow the direction of a well-tempered judgement, being neither led astray by fear or the allurement of immediate pleasure, nor carried away by rash impulse. Whatever is clearly at variance with such judgement is understood to be contrary also to the law of nature; that is, to the nature of man. …

Least of all should that be admitted which some people imagine, that in war all laws are in abeyance. On the contrary war ought not to be undertaken except for the enforcement of rights ; when once undertaken, it should be carried on only within the bounds of law and good faith. Demosthenes well said that war is directed against those who cannot be held in check by judicial processes. For judgements are efficacious against those who feel that they are too weak to resist; against those who are equally strong, or think that they are, wars [xii] are undertaken. But in order that wars may be justified, they must be carried on with not less scrupulousness than judicial processes are wont to be.

Let the laws be silent, then, in the midst of arms, but only the laws of the State, those that the courts are concerned with, that are adapted only to a state of peace; not those other laws, which are of perpetual validity and suited to all times.

See a larger version of 1800×3050 px

My analysis of the allegories used in the picture follows:

Standing on a round temple is Justice (she holds the scales of justice in her right hand) above Mars (war) who holds a sword in his right hand, next to whom is Peace or Abundance who holds a compass in her left hand (to measure out quantities), over which is draped a snake which is biting its own tail in a circle (a symbol of eternity), and who holds in her right hand the cornucopia (the horn of plenty). On either side of them and slightly behind are some shadowy figures whose meaning is not clear. Mars’ sword points to the left and in the distance is Neptune with his trident and his chariot pulled by horses. Since Holland and England were both aspiring sea powers this may be a reference to this fact. At the foot of the temple at the right are two figures, a man wearing a helmet who is holding another snake over a fire with his right hand (perhaps here a symbol of evil) and with his left holding a woman around her waste; she is a peasant girl who is wearing a bonnet and a yoke around her shoulders (a symbol of submission) and in her left hand an hour glass (a symbol of the passage of time and of death). At the left is a bearded man in the shadows who is also holding a snake over a fire. At the very bottom of the picture is a dead boar (a symbol of lust and ferocity) which has been sacrificed.

For further material by Grotius see:

- the main page for Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) which has links to the facsimile PDFs of the 1625 and 1670 editions in Latin

- an incomplete English translation done at the time of International Peace Conference at The Hague July 4th, 1899, with an introduction by David J. Hill, Assistant Secretary of State of the United States; and with a dedication “To the Memory of Hugo Grotius in Reverence and Gratitude from the United States of America” HTML

- and an 1925 edition edited by James Brown Scott for the Carnegie Institution, from which I made an HTML version of Grotius’ Prolegomena to the Three Books on The Law Of War And Peace” (1625, 1925)