See the full paper at my main website.

This is part of a book-length “introduction” (300 pp.) I have written to the translation of Molinari’s Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849). It includes a brief biography of Molinari; a discussion of the struggle against protection in France from the 1820s to the late 1840s; the socialist attack on private property and the legitimacy of profit, interest and rent in the 1840s; a brief history of the popularisation of economic theory and the role played by the “conversation” format; Molinari’s and the economists’ activities during the 1848 Revolution; and Molinari’s theory of liberty and the “natural laws” of political economy which he presents in Les Soirées.

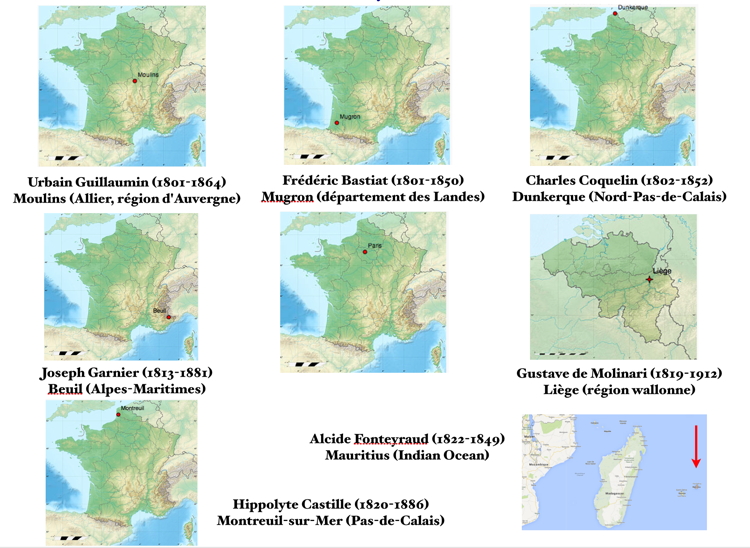

Abstract: In Paris in the 1840s there emerged a very special and unique collection of individuals who came together to promote classical liberal and free market thought and to fight socialism and interventionism. I call them “the Seven Musketeers” of French political economy. The term “Musketeer” comes from Gérard Minart’s new biography of Gustave de Molinari (2012) in which he described Frédéric Bastiat, Molinari, and 2 other colleagues (Guillaumin, Coquelin) as “The Four Musketeers”. This is quite appropriate as Dumas’ popular novel came out in 1844 [it was serialised in Le Siècle] and Bastiat, like D’Artagnan, came from the south-west province of Gascony. These economists formed a close band of liberal intellectuals and activists in Paris who were fighting protectionism and socialism not the Protestant enemies of the King of France as the original Musketeers were. My research has revealed that 7 individuals actually fit this description. They are made up of two generations who were key figures in the classical liberal and political economy movement. The 1st were born around 1800 and were in their mid to late 40s in 1848; the 2nd were born around 1820 and were in their late 20s in 1848.

The first generation comprised the publisher Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-1864) whose firm published books, pamphlets, and the Journal des Économistes (1841-1940), he was the intellectual entrepreneur who brought people together, organised the funding of the movement, and helped set up important organisations like the Political Economy Society; Charles Coquelin (1802-1852) who was an economist who specialised in free banking, was an eloquent public speaker, and editor of the monumental Dictionnaire de l’Économie politique (1852); and the relative late-comer Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) who was a free trade activist and journalist, a brilliant popularizer of economic thought, an economic theorist ahead of his time, head of the French Free Trade Association, and editor of its journal Le Libre-Échange (1846-48).

The second generation was made up of Joseph Garnier (1813-1881) who was an economics teacher, editor, and peace advocate; Hippolyte Castille (1820-1886) who was a journalist, popular historian, wrote for le Courrier français, and held regular soirées at his home on the rue Saint-Lazare (1843?-48); Alcide Fonteyraud (1822-1849) who was a specialist on Ricardo, a translator, and a gifted public speaker; and Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) who was a journalist, an economic theorist, and a sociologist. Molinari’s work on the private provision of all public goods (including police and defence) also appeared at this time.

These seven people came together for brief period in late the 1840s and early 1850s and changed French classical liberalism in a profound manner.They lobbied the government for tariff reform, organised a nation-wide free trade movement, took to the streets in the middle of the 1848 Revolution to hand out free market material to the rioting workers, stood successfully for election, organised an anti-socialist campaign with a stream of pamphlets and popular books, and organised an international Peace Conference. The organisations which they either founded or were active in included the following: the Guillaumin publishing firm 1835-1910; the Société d’économie politique (SEP) (founded 1842); the Journal des Économistes (JDE) (founded 1841-42, closed down in 1940 after the Nazi occupation of Paris); teaching economics in schools such as the Athénée and Collège de France; Castille’s Soirées 1843??-1848: the French Free Trade Association (FTA) (active 1846-48); activities during the February Revolution such as street journalism, the political club “Club for the Freedom of Working”, and an organised political faction in the Constituent Assembly; J. Garnier’s Friends of Peace conference; and the Académie français (reconstituted 1832) .

By 1852 they had largely dispersed through a combination of early deaths, political reaction, and exile. In addition to making an indelible mark on the classical liberal movement they also show the importance of outsiders who migrate to a city and enrich its intellectual life with new and radical ways of thinking.