Date: 1 Dec. 2014

A paper on “Seeing the ‘Unseen’ Bastiat: the changing Optics of Bastiat Studies. Or, what the Liberty Fund’s Translation Project is teaching us about Bastiat” given to the “Colloquium on Market Institutions & Economic Processes” at NYU

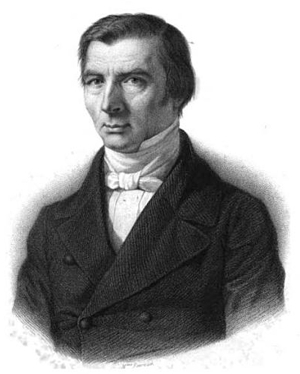

Abstract: The translation project being undertaken by Liberty Fund to translate the Collected Works of Frédéric Bastiat provides us with an opportunity to reassess the work of this mid-19th century French political economist. This paper examines the changing perception of Bastiat’s work from the late 1840s until the conference held in Mugron in June 2001 to celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birth when the decision was made to translate into English all of his available work for the first time. His contemporaries recognized his talents as a brilliant economic journalist, a free trade activist, and an elected politician who dabbled in economic theory but died in 1850 before he could complete his work. His reputation went into decline for the next 100 years as his approach to economics went against first the classical and then the neo-classical schools. Except for a very few economists like W.S. Jevons Bastiat was dismissed as a serious economic theorist. Joseph Schumpeter summed up the consensus view in 1954 describing him as not a theorist at all.

Even as Schumpeter was writing these words a rediscovery of Bastiat was taking place in New York with the first modern translation effort of some of his work by the Foundation for Economic Freedom in Irvington-on-Hudson and the students who attended Mises’ Seminar at NYU who formed the Circle Bastiat (especially Rothbard, Raico, and Liggio who went on to do important research on French classical liberal thought). Since then there has a been a steady though still small growth in interest in Bastiat’s work as an economist. To encourage this growth Liberty Fund decided to translate the entire corpus of his work in order to provide a better foundation for scholars to study his work. Only 25% of his available writings had been translated by FEE in the 1960s. The LF translation project will include his collected correspondence (vol. 1), a complete collection of his Economic Sophisms (vol. 3), all of his political and economic essays and articles (vols. 1, 2, 4), all of his free trade journalism and public speeches (vol. 6), and a critical edition of his unfinished magnum opus Economic Harmonies (vol. 5). It should also be noted that a similar rediscovery of the work of Bastiat is currently taking place in France, so this is a trans-atlantic phenomenon.

As Academic Editor for the project I can attest that there are many things which have hitherto been ignored or not known about the life and work of Bastiat which throw important light on the originality of Bastiat as an economic and social theorist, the interlocking networks of other classical liberals and economists with whom he worked in Paris in the late 1848s, and the reaction of the economists to the February Revolution of 1848 and the effort by socialists like Louis Blanc to create the first modern welfare state. I conclude by assessing the claims made by some contemporary economists that Bastiat was in fact an “Austrian” economist or perhaps even a “Public Choice” economist avant la lettre.