A Paper given at the “History of Thought” Session of the Society for the Development of Austrian Economics.

Southern Economic Association 83rd Annual Meeting,

November 23-25, 2013

Tampa, Florida

The paper is online here

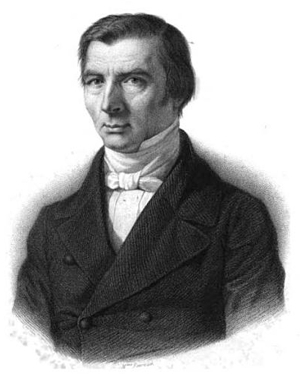

In this paper I would like to examine a theory Bastiat developed in the latter years of his life (1847-1850) on calculating the costs and benefits of what he called “the unseen”. This is an important part of Bastiat’s economic theory which has been ignored by researchers to date, partly because the relevant articles were not included in the FEE translation of his Economic Sophisms (but which will be included in LF’s new translation of the complete Sophisms), partly because of mistranslations of those that have been translated (the key word “ricochet” was often translated figuratively, often as “indirect” or “rebounds”, and not as the technical economic word Bastiat intended it to be), and partly because a full electronic version of his complete works did not exist until recently when comprehensive key word searches could be used for the first time to uncover the rich and colorful vocabulary Bastiat used in formulating his ideas on this topic.

The methodology used in this paper is a combination of history of ideas and linguistic analysis of his and other contemporary writings.

I will begin with a discussion of the idea of “the double incidence of loss” which Bastiat borrowed from the English free trader Perronet Thompson, Bastiat’s expansion of this idea, which originally included only three parties, to one which included many (perhaps millions) of interconnected parties in an economy (“the ricochet effect”), his failed attempts to use mathematics to scientifically calculate the losses caused by government interventions in the economy or by natural disasters, and his realization that there could be positive ricochet effects (PRE) as well as the negative ricochet effects (NRE) which is what he was most interested in when he began his analysis.

Bastiat’s theory of “the ricochet effect” led him to think about concepts such as opportunity costs, the multiplier effect (positive and negative), the use of mathematics to quantify costs and benefits of economic actions, the use of thought experiments (“Crusoe economics” and stories about the French everyman “Jacques Bonhomme”) to explore the nature of human action in the abstract (praxeology), the interconnectedness of all economic activity, the idea of unintended consequences, and the transmission of economic information to other economic actors via information “flows”.

This analysis only proves yet again what a loss his premature death was in 1850. The originality and richness of his ideas are striking and one can only speculate what he might have done to develop them had he lived longer.