Source of Data

Benoît Malbranque, “Liste complète des titres publiés par Guillaumin (1837-1910)”, Institut Coppet (janvier 2, 2017) here.

David M. Hart, “Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-64) and the Guillaumin Publishing Firm (1837-1910)” with my list of their titles. It also contains many links to individual Guillaumin book catalogs which were often appended to the books they published. I have plucked them out as I was editing the books to go online. Here.

See also my essay on “The Paris School of Political Economy 1803-1853” here and my main page on “The Paris School of Political Economy” on my website.

Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-64)

The book publisher and classical liberal activist Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-64). Guillaumin was a mid-19th century French classical liberal publisher who founded a publishing dynasty which lasted from 1835 to around 1910 and became the focal point for the classical liberal movement in France.

Guillaumin was orphaned at the age of five and was brought up by his uncle. He came to Paris in 1819 and worked in a bookstore before eventually founding his own b bookshop and publishing firm in 1835. He became active in liberal politics during the July Monarchy after the revolution of 1830 and made contact with a number of free market economists. He became a publisher in 1835 in order to popularize and promote classical liberal economic ideas, and the firm of Guillaumin eventually became the major publishing house for classical liberal ideas in 19th century France. Guillaumin helped found the Journal des économistes in 1841 and the following year he helped found the Société d’économie politique which became the main organization which brought like-minded classical liberals together for discussion and debate.

The business was located in the Rue Richelieu, no. 14, in a very central part of Paris not far from the River Seine, the Tuileries Gardens, the Louvre Museum, the Palais Royal, the Comédie Française theatre, and the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The above picture postcard shows the Molière fountain at the intersection of the Rue Richelieu (left) and the Rue Moliére (right) near the Théâtre du Palais Royal. The fountain was built in 1844 opposite the building, 40 Rue Richelieu, where Molière had once lived. The office which housed the Librairie de Guillaumin et Cie would have been about half way down the Rue Richelieu from the fountain.

His firm “Guillaumin” published hundreds of books on economic issues, making its catalog a virtual who’s who of the liberal movement in France. Their 1866 catalog listed 166 separate book titles, not counting journals and other periodicals. For example, he published the works of Jean-Baptiste Say, Charles Dunoyer, Frédéric Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari and many others, including translations of works by Hugo Grotius, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Charles Darwin.

By the mid-1840s Guillaumin’s home and business had become the focal point of the classical liberal lobby in Paris which debated and published material opposed to a number of causes which they believed threatened liberty in France: statism, protectionism, socialism, militarism, and colonialism. The historian Gérard Minart coined the term “le réseau Guillaumin” (the Guillaumin network) to describe the interconnected commercial, intellectual, political, and personal links which existed between the various liberal groups which met in or around the firm’s headquarters in Paris for several decades.

After his death in 1864 the firm’s activities were continued by his oldest daughter Félicité, and after her death it was handed over to his youngest daughter Pauline. The firm of Guillaumin continued in one form or another from 1835 to 1910 when it was merged with the publisher Félix Alcan.

Key Texts published between 1837 and 1852

During the period I am most interested in (1837-1852 – 16 years) the firm published 360 titles at an average rate of 22.5 p.a. Some of the more important and innovative of those texts are listed below. They include texts which were in fact published as well as those which must have been in production during that time and appeared very shortly afterwards. Who decided what titles to commission and publish and what criteria they used to choose them are not known. One can only infer that Gilbert Guillaumin as owner and founder of the firm had a strong say in this editorial policy.

- Encyclopédie du commerçant. Dictionnaire du commerce et des marchandises, 2 vols. (1837-39)

- Adolphe Blanqui, Histoire de l’économie politique en Europe depuis les anciens jusqu’à nos jours (1837)

- Louis Reybaud, Études sur les réformateurs contemporains ou socialistes modernes (1840)

- Journal des économistes, (1841-). Editors: Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (December 1841), Adolphe Blanqui (1842-43), Hippolyte Dussard (1843-45), Joseph Garnier (1845-55).

- Collection des principaux économistes, ed. Daire et al. (1840-48), 15 vols. Works by Say (1840, 1841), Boisguillebert (1843), Adam Smith (1843), Turgot (1844), Quesnay (1846), Condillac, Condorcet (1847) and translations of Malthus (1845, 1846), Ricardo (1847), Hume (1847-48), Franklin (1847-48), Bentham (1847-48).

- Annuaire de l’économie politique et de la statistique, 56 vols. (1844-1899)

- Dunoyer, De la Liberté du travail, 3 vols. (1845)

- Bastiat, Cobden et la ligue, ou l’Agitation anglaise pour la liberté du commerce, (1845)

- P.-J. Proudhon, Système des contradictions économiques ou Philosophie de la misère (1846)

- Bastiat, Sophismes économiques (1st series 1846, 2nd 1848)

- Molinari , Histoire du tarif (1847)

- Coquelin, Du Crédit et des Banques (1848)

- Garnier, Le droit au travail à l’Assemblée nationale : recueil complet de tous les discours prononcés (1848)

- Molinari, “De la Production de la sécurité,* (extrait du Journal des économistes) (1849)

- Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849)

- Bastiat, Harmonies économiques (1850, 1851)

- Bastiat, La Loi (1850)

- Garnier, Congrès des amis de la paix universelle réuni à Paris en 1849 (1850)

- Bastiat, Ce que l’on voit et ce que l’on ne voit pas ou l’économie politique en une leçon (1850)

- Gratuité du crédit, discussion entre M. Fr. Bastiat et M. Proudhon (version augmentée éditée par F. Bastiat) (1850)

- Bastiat, Harmonies économiques, 2ème édition augmentée (1851)

- MacCulloch , Principes d’économie politique (1851)

- Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, ed. Coquelin et Guillaumin, 2 vols. (1852-53)

- Fonteyraud, Mélanges d’économie politique (1853)

- Œuvres complètes de Frédéric Bastiat, 6 vol. (1854-1855)

I think the “jewell in the crown” of the Guillaumin firm in the early period was the monumental, 2 volume Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (1852-53) which was edited by Coquelin et Guillaumin himself. The DEP is a two volume, 1,854 page, double-columned encyclopedia of political economy and is unquestionably one of the most important publishing events in the history of 19th century French classical liberal thought and is unequalled in its scope and comprehensiveness. The aim was to assemble a compendium of the state of knowledge of liberal political economy with articles written by leading economists on key topics, biographies of important historical figures, annotated bibliographies of the most important books in the field, and tables of economic and political statistics.

The Economists believed that the events of the 1848 Revolution had shown how poorly understood the principles of economics were among the French public, especially its political and intellectual elites. One of the tasks of the DEP was to rectify this situation with an easily accessible summary of the entire discipline. The major contributors were the editor Charles Coquelin (with 70 major articles), Gustave de Molinari (29), Horace Say (29), Joseph Garnier (28), Ambroise Clément (22), Courcelle-Seneuil (21), and Maurice Block wrote most of the biographical entries.

Analysis of the Yearly Publication of Titles

Using the publishing data from Malbranque and my own lists of titles I have determined that:

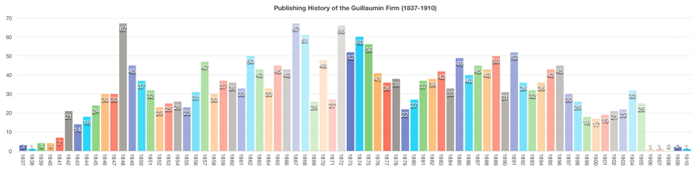

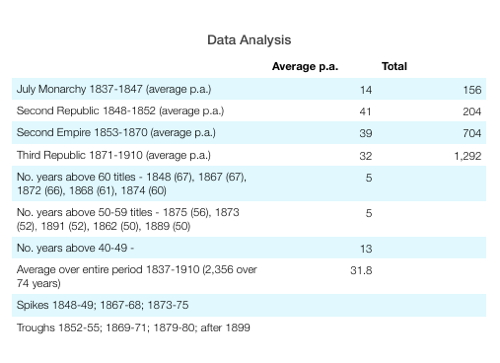

- between 1837 and 1910 (74 years) the Guillaumin firm published 2,356 titles at an average of 31.8 titles p.a.

- during the period we are interested in (1837-1852 – 16 years) the firm published 360 titles at an average of 22.5 p.a.

- during the July Monarchy (1837-1847) 156 titles were published at an average of 14 p.a.

- during the Second Republic (1848-1852) 204 titles were published at an average of 41 p.a.

- during the Second Empire (1853-1870) 704 titles were published at an average of 39 p.a.

- there were 5 years when 60 or more titles were published: 848 (67), 1867 (67), 1872 (66), 1868 (61), 1874 (60)

- there were 5 years when 50-59 titles were published: 1875 (56), 1873 (52), 1891 (52), 1862 (50), 1889 (50)

- we can see three periods when their activity spiked: 1848-49; 1867-68; 1873-75

- and three periods when there were troughs: 1852-55; 1869-71; 1879-80;

- and a general falling off of activity after 1899

Graph of Books Published by Year

See a larger version of this image (1470×360 px).

Data Summary