Here we have an official a portrait of Charles Stuart (1600-1649) done in the studio of Anthony van Dyck c. 1636. He is of course at the height of his powers and in his full regal regalia. He ruled from 1625 to 1649 when he was executed by Parliament.

When he was in prison awaiting his sentence and then execution Charles Stuart (King Charles I) wrote a defence of himself, his position, and his actions during the Civil Wars which he called “The Image or Icon of the King” (“Eikon Basilke” in Greek) which included some self-serving images, most notably a very detailed Frontispiece.

The full title of the book was: Εἰκὼν Βασιλική (the Image of the King), The Pourtrature of His Sacred Majestie in His Solitudes and Sufferings (1649) which we have put online. See the facs. PDF of the first edition – with the frontispiece and one without. Also an HTML version of the 1904 edition by Almack.

There were two demolitions of this “iconography of the king”, one a satirical image suggesting he was a mere puppet of the Catholic Church, and one in print by Milton denouncing Charles as a tyrant who deserved his death, in Eikonoklastes (the “iconoclast” or the destroyer of images) [HTML] and The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates [HTML] which Milton also published in 1649 and which was his second defence of regicide. As he subtitled The Tenure of Kings, “That it is Lawfull, and hath been held so through all Ages, for any who have the Power, to call to account a Tyrant, or wicked KING, and after due conviction, to depose and put him to death; if the ordinary MAGISTRATE have neglected or deny’d to doe it”.

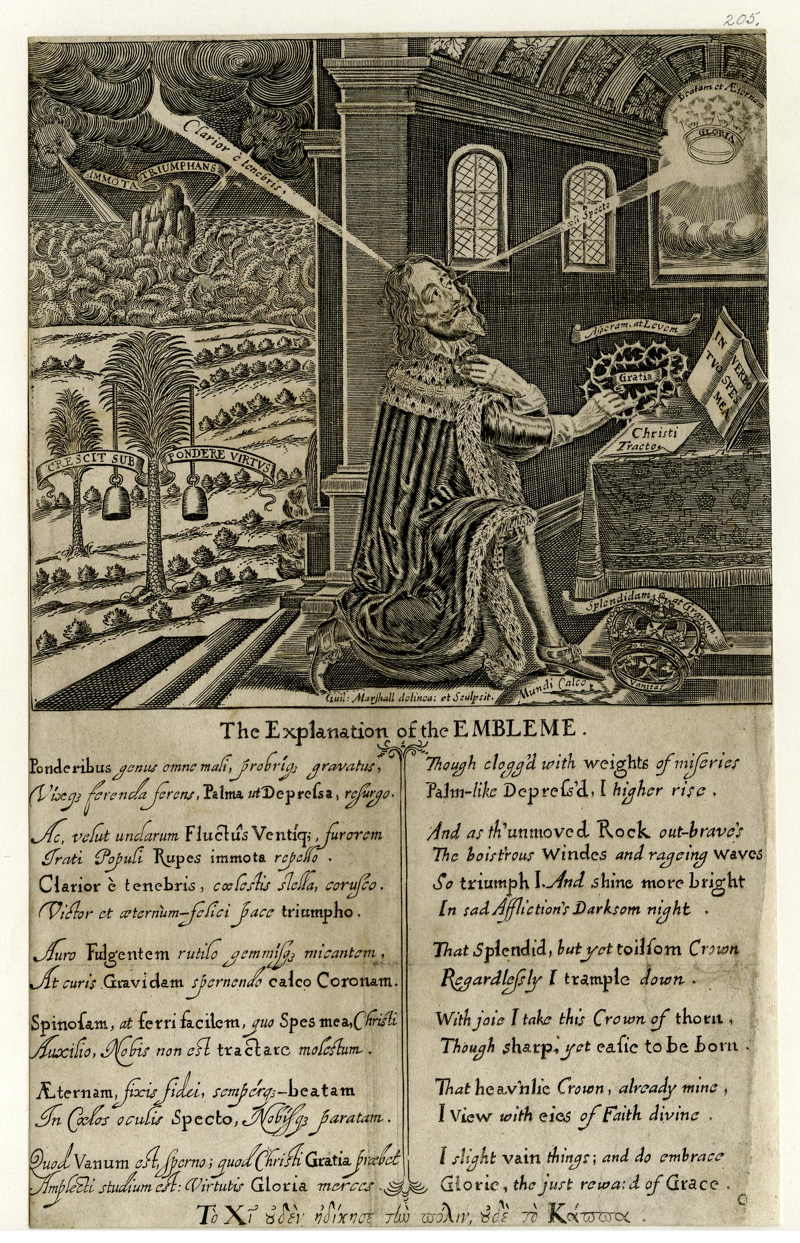

The Official Frontispiece

See also a slightly different and larger version: larger size 3162×2717 pixels.

Charles is depicted dressed in his finest robes and kneeling in what appears to be a small chapel. A beam of light from heaven (“sacred heat”) breaks through the dark clouds outside on the left and strikes him on the top of his head. At the same moment he is looking heavensward towards the upper right and sees one of the three crowns in the picture. This is “his” “Starrie Crown

of Gloirie ” which will be his after his execution. The world outside the chapel on the left is a scene of physical and man-made torment. Nature is pounding the rock (Charles is the rock) with violent waves and fierce storms (the civil wars and revolution of the past 7 years), but it/he stands “unmov’d triumphant”. In the fields stands a palm tree (another symbol of Charles) on which have been hung two heavy weights which one would think were designed to prevent it growing too tall (constitutional limits on his power?) but which have the opposite effect of causing it/him to grow (more straight and high). At his feet there is the second crown (his earthly crown) in the picture which lies at his feet (knocked from his head by the Parliamentary regicides and republicans) and which he now “disdains”, He now turns for solace to the Bible while holding the third crown, Christ’s “crown of thorns”, as he sees himslef as a martyr to the cause of monarchy and God.

In one edition from 1649 there is this “Explanation of the Frontispiece”:

A Sacred heat inspires my Soul to trie

If Pray’rs can give Me what the Warres denie,

Three Crowns distinctly here in order do

Present their objects to my knowing view,

Earths Crown lies humbled at my foot, disdain,

‘Twas bright, but heavie, and withal but vain,

And now by Grace a Crown of Thorns I greet.

Sharp was this Crown, but not so sharp as sweet:

This was Christs crown, my book upon my bord

Explains my heart, My hope is in thy Word.

My Starrie Crown

of Gloirie last I see,

As full of Blisse, as of Eternitie.

Now look behind, and midst most troubled skies

Behold, how clearer I from darknesse rise,

And stand unmov’d triumphant, like a Rock,

‘Gainst all the waves, & winds tempestuous shock

So like the Psalm, which heaviest weights do trie,

Virtue opprest, doth grow more straight and high.

In another editon there is a Latin and English key to the emblems:

The English reads:

Though clogg’d with weights of miseries

Palm-like Depress’d, I higher rise.And as th’unmoved Rock out-brave’s

The boist’rous Windes and rageing waves

So triumph I. And shine more bright

In sad Affliction’s Darksom night.That Splendid, but yet toilsom Crown

Regardlessly I trample down.With joie I take this Crown of thorn,

Though sharp, yet easy to be born.That heavn’nly Crown, already mine,

I view with eies of Faith divine.I slight vain things: and do embrace

Glorie, the just reward of Grace.

The Latin incrsiptions and labels in the large version of the Frontispiece are as follows in a literal translation:

- IMMOTA, TRIVMPHANS — “Unmoved, Triumphant” (scroll around the rock);

- Clarior é tenebris — “Brighter through the darkness” (beam from the clouds);

- CRESCIT SUB PONDERE VIRTVS — “Virtue grows beneath weights” (scroll around the tree);

- Beatam & Æternam — “Blessed and Eternal” (around the heavenly crown marked GLORIA (“Glory”); meant to be contrasted with:

- Splendidam & Gravem — “Splendid and Heavy” (around the Crown of England, removed from the King’s head and lying on the ground), with the motto Vanitas (“vanity“); and

- Asperam & Levem — “Bitter and Light”, the martyr’s crown of thorns held by Charles; contains the motto Gratia (“grace”);

- Coeli Specto — “I look to Heaven”;

- IN VERBO TVO SPES MEA — “In Thy Word is My Hope”;

- Christi Tracto — “I entreat Christ” or “By the word of Christ”;

- Mundi Calco — “I tread on the world”.

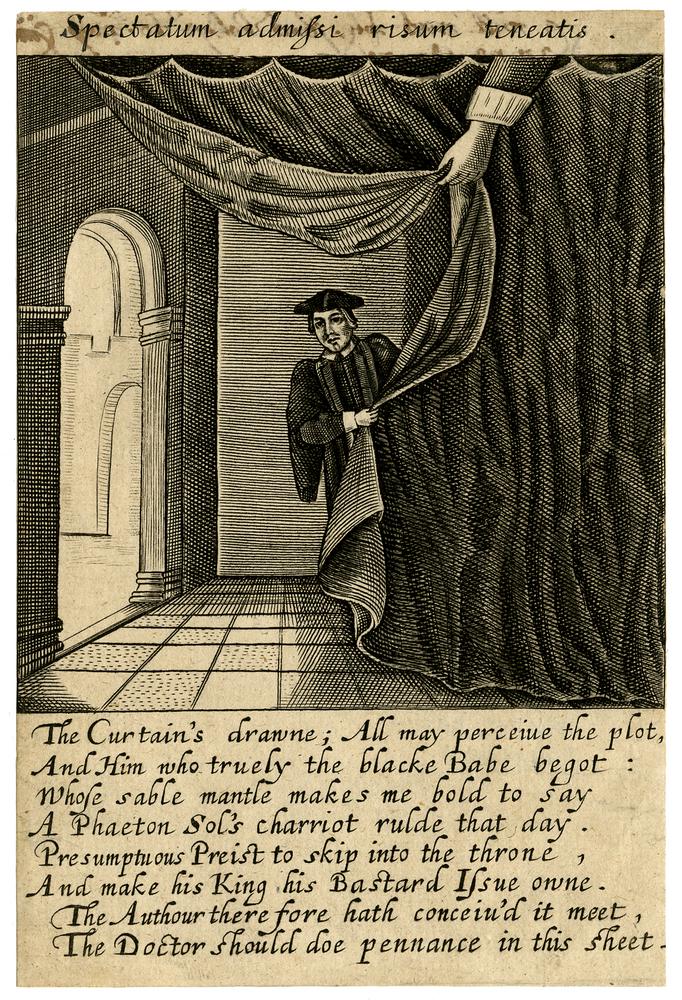

A Satirical Version of the Frontispiece

There is a satirical print held by the British Museum <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_P-2-43> from a book called Eikon alethine (The True Ikon or Image)) which mocks the idea that Charles had the brains to write a defense of his monarchy and that he had been manipulated as a puppet of the Church.

The image has the title “Spectatum admissi risum teneatis” (If you saw such a thing, could you restrain your laughter – a quote from Horace, Ars Poetica V) and reveals a cleric who had been hiding behind a curtain which has been pulled back by a hand reaching down from above (much like a hand in the Monty Python TV show). The poem below the image states:

The Curtain’s drawne; All may perceive the plot,

And Him who truely the blacke Babe begot:

Whose sable mantle makes me bold to say

A Phaeton Sol’s chariot ruled that day.

Presumptuous Priest to skip into the throne,

And make his King his Bastard Issue owne.

The Author therefore hath conceiv’d it meet,

The Doctor should doe pennance in this sheet.

Milton’s “Iconoclasm”, or the Smashing of Political Idolatry

Milton was very aware of what Charles and his supporters were attemtping to do in publishing the Eikon Basilike with its emblems of power in the Frontispiece, as these comments in the Preface show very clearly. I have put in bold some of the most striking passages:

First, then, that some men (whether this were by him intended, or by his friends) have by policy accomplished after death that revenge upon their enemies, which in life they were not able, hath been oft related. And among other examples we find, that the last will of Cæsar being read to the people, and what bounteous legacies he had bequeathed them, wrought more in that vulgar audience to the avenging of his death, than all the art he could ever use to win their favour in his lifetime. And how much their intent, who published these overlate apologies and meditations of the dead king, drives to the same end of stirring up the people to bring him that honour, that affection, and by consequence that revenge to his dead corpse, which he himself living could never gain to his person, it appears both by the conceited portraiture before his book, drawn out to the full measure of a masking scene, and set there to catch fools and silly gazers; and by those Latin words after the end, Vota dabunt quæ bella negarunt; intimating, that what he could not compass by war, he should achieve by his meditations: for in words which admit of various sense, the liberty is ours, to choose that interpretation, which may best mind us of what our restless enemies endeavour, and what we are timely to prevent. And here may be well observed the loose and negligent curiosity of those, who took upon them to adorn the setting out of this book; for though the picture set in front would martyr him and saint him to befool the people, yet the Latin motto in the end [Vota dabunt, quae bella negârunt], which they understand not, leaves him, as it were, a politic contriver to bring about that interest, by fair and plausible words, which the force of arms denied him. But quaint emblems and devices, begged from the old pageantry of some twelfthnight’s entertainment at Whitehall, will do but ill to make a saint or martyr: and if the people resolve to take him sainted at the rate of such a canonizing, I shall suspect their calendar more than the Gregorian. In one thing I must commend his openness, who gave the title to this book, Εἰκὼν Βασιλική, that is to say, The King’s Image; and by the shrine he dresses out for him, certainly would have the people come and worship him. For which reason this answer also is entitled, Iconoclastes, the famous surname of many Greek emperors, who in their zeal to the command of God, after long tradition of idolatry in the church, took courage and broke all superstitious images to pieces. But the people, exorbitant and excessive in all their motions, are prone ofttimes not to a religious only, but to a civil kind of idolatry, in idolizing their kings: though never more mistaken in the object of their worship; heretofore being won’t to repute for saints those faithful and courageous barons, who lost their lives in the field, making glorious war against tyrants for the common liberty; as Simon de Momfort, earl of Leicester, against Henry the IIId; Thomas Plantagenet, earl of Lancaster, against Edward IId. But now, with a besotted and degenerate baseness of spirit, except some few who yet retain in them the old English fortitude and love of freedom, and have testified it by their matchless deeds, the rest, imbastardized from the ancient nobleness of their ancestors, are ready to fall flat and give adoration to the image and memory of this man, who hath offered at more cunning fetches to undermine our liberties, and put tyranny into an art, than any British king before him: …

A very hard-hitting and quite funny rhetorical device which is so typical of Milton the political pamphleteer was to compare the desire of Charles to dominate Parliament (the “mother” of English liberty) and usurp its law-making capacity to that of the sun giving life-giving energy to the soil before anything could grow, or even more wickedly to compare Charles to a “mother-fucker” (the masculine tyrant raping “mother” Parliament) as this passage discussing Section XI “Upon the Nineteen Propositions” shows:

Yet so far doth self opinion or false principles delude and transport him, as to think “the concurrence of his reason” to the votes of parliament, not only political, but natural, “and as necessary to the begetting,” or bringing forth of any one “complete act of public wisdom as the sun’s influence is necessary to all nature’s productions.” So that the parliament, it seems, is but a female, and without his procreative reason, the laws which they can produce are but wind-eggs: wisdom, it seems, to a king is natural, to a parliament not natural, but by conjunction with the king; yet he professes to hold his kingly right by law; and if no law could be made but by the great council of a nation, which we now term a parliament, then certainly it was a parliament that first created kings; and not only made laws before a king was in being, but those laws especially whereby he holds his crown. He ought then to have so thought of a parliament, if he count it not male, as of his mother, which to civil being created both him and the royalty he wore. And if it hath been anciently interpreted the presaging sign of a future tyrant, but to dream of copulation with his mother, what can it be less than actual tyranny to affirm waking, that the parliament, which is his mother, can neither conceive or bring forth “any authoritative act” without his masculine coition? Nay, that his reason is as celestial and life-giving to the parliament, as the sun’s influence is to the earth: what other notions but these, or such like, could swell up Caligula to think himself a god?

No wonder that that the restored Stuarts put a price on Milton’s head and wanted to destroy all his books and pamphlets.