JOHN WADE,

The Black Book: An Exposition of Abuses in Church and State, Courts of Law, Municipal Corporations, and Public Companies (1835)

|

[Created: 7 May, 2023]

[Updated: May 18, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, The Black Book: An Exposition of Abuses in Church and State, Courts of Law, Municipal Corporations, and Public Companies; With a Précis of the House of Commons, Past, Present, and to Come. A New Edition, greatly enlarged and corrected. By the original Editor. With an Appendix. (London: Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange. MDCCCXXXV (1835).)http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1835-Wade_BlackBook/Wade_BlackBook1835-ebook.html

John Wade, The Black Book: An Exposition of Abuses in Church and State, Courts of Law, Municipal Corporations, and Public Companies; With a Précis of the House of Commons, Past, Present, and to Come. A New Edition, greatly enlarged and corrected. By the original Editor. With an Appendix. (London: Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange. MDCCCXXXV (1835).)

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

CONTENTS. [Abbreviated]

- Advertisement to the New Edition, p. Page iii

- Address to the New Edition, p. vii

- Dedication to the People, p. xi

- ADDENDUM: MINISTERIAL PLANS ON TITHES, p. xxxi

- CHAPTER I. CHURCH OF ENGLAND., p. 1

- CHAPTER II., p. 96

- CHAPTER III. CHURCH OF IRELAND., p. 138

- CHAPTER IV. REVENUES OF THE CROWN. p. 184

- CHAPTER V. CIVIL LIST. p. 212

- CHAPTER VI. PRIVY COUNCIL—DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS—AND CONSULAR ESTABLISHMENTS., p. 244

- CHAPTER VII. THE ARISTOCRACY. p. 254

- CHAPTER VIII. LAW AND COURTS OF LAW. p. 286

- CHAPTER IX. PROGRESS OF THE PUBLIC DEBT AND TAXES. p. 334

- CHAPTER X. EXPOSITION OF THE FUNDING-SYSTEM. p. 343

- CHAPTER XI. TAXATION AND GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE. p. 366

- CHAPTER XII. THE EAST INDIA COMPANY. p. 394

- CHAPTER XIII. THE BANK OF ENGLAND. p. 428

- CHAPTER XIV. MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS, COMPANIES, GUILDS, AND FRATERNITIES. p. 452

- CHAPTER XV. PLACES, PENSIONS, SINECURES, REVERSIONS, HALF-PAY, AND SUPERANNUATIONS. p. 479

- CHAPTER XVI. Alphabetic list of placemen, pensioners, sinecurists, compensationists, and grantees., p. 505

- CHAPTER XVII. HOUSE OF COMMONS, PAST, PRESENT, AND TO COME., p. 591

- APPENDIX. p. 627

- Endnotes

[xv]

CONTENTS.

- Advertisement to the New Edition, p. Page iii

- Address to the New Edition, p. vii

- Dedication to the People, p. xi

- ADDENDUM: MINISTERIAL PLANS ON TITHES, p. xxxi

- CHAPTER I. CHURCH OF ENGLAND.

- Introduction:—Christianity peculiarly the worship of the people 1

- Conduct of public men in respect of religious institutions, p. 2

- Tyburn or Tartarus the needful moral restraint of some persons, p. 3

- England—the only country to which ecclesiastical reform has not extended, p. 4

- The un-Christian conduct of the established Clergy—supporters of aristocratic wars—favourable to the African slave-trade—not favourable to education—not given to charity—and communicate little useful knowledge to the people, p. 6

- Religious opinions determined by education, p. 8

- Division of the subject, p. 9

- I.—origin and tenure of church property.

- Origin and fourfold division of tithes, p. 10

- New disposition of ecclesiastical property at the Reformation, p. 13

- Church property proved to be public property from legislative acts 16

- Eagle’s Legal Argument on tithes, p. 17

- Tenure of the clergy—same as other public functionaries, p. 18

- Clergy, tenants-at-will, may be ejected by their parliamentary landlords, p. 19

- II.—patronage of the church.

- Dr. Lushington’s error in considering advowsons private property 19

- Evasion of the laws against simony, p. 20

- Jews and Infidels may select persons for the Gospel ministry, p. 20

- Instance of sale advowsons, p. 21

- Patronage among the bishops, the king, aristocracy, and gentry, p. 21

- Recommendations of the present bishops to promotion, p. 23

- Examples of perversion of patronage by bishops Sparke, Sutton, and Pretyman, p. 24

- Clerical monopoly illustrated by examples, p. 28

- Number of the clergy and number of preferments shared among them, p. 30

- Singular division of parochial benefices into pluralities, p. 30

- More than one-third of incumbents pluralists, p. 31

- III.—sinecurism.—non-residence.—pluralities.—church discipline.

- Uncouth habiliments and dress of the clergy, p. 32

- Duties of the several orders of clergy, p. 33

- Discoveries of Mr. Wright on church discipline, p. 34

- Pretexts of the clergy for non-residence, p. 35

- Parsons’ indemnity bill, p. 39

- Dr. Johnson’s employment before he received a pension, p. 40

- Primate Sutton’s principle of church government, p. 41

- The priestly motto on Lambeth window, p. 41

- IV.—revenues of the established church.

- Suggestions for an authentic return of ecclesiastical revenues, p. 42

- Examples of increase in value of church property, p. 43

- Quarterly Review’s estimate of church revenues, p. 45

- Estimate of value of sees from authentic data, p. 47

- Lectureships, public charities, surplice fees, new churches, and other sources of clerical income, p. 48

- General Statement of church revenues, from tithe, church fees, &c. 52

- Revenues of the church monopolized by 7694 individuals, p. 53

- Impositions practised in repect of poor livings, p. 55

- Question briefly stated—Bishops, Dignitaries, and Aristocratic Pluralists, chiefly engross church income, p. 56

- Church of England without Poor Clergy, unless it be curates, p. 58

- Proportion in which revenues are divided among the several orders of clergy, p. 58

- Observations on unequal division of ecclesiastical revenues, p. 59

- Comparative cost of Church of England and other churches, p. 63

- V.—rapacity of the clergy exemplified.

- Conduct of the rich clergy in respect of First Fruits, p. 64

- Rapacious claims of the London clergy, p. 67

- True policy of the church expounded, p. 70

- Conduct of the clergy in respect of tithe compositions, p. 71

- Dean and chapter of Ely’s rapacious claim, p. 71

- Mode suggested for retaliating on the clergy, p. 72

- IV.—origin and defects of the church liturgy.

- Dr. Middleton’s researches in church history, p. 73

- Similarity of Catholic and Church of England worship, p. 74

- Opposite conduct of Whigs and Tories in respect of religion, p. 75

- Defects in the book of Common Prayer, p. 76

- Church Catechism, p. 77

- Strange mode of ordaining priests, p. 78

- Preference of church service to the random out-pourings of the conventicle, p. 79

- VII.—numbers, wealth, moral and educational efficiency of the dissenters.

- Dissenters, like Roman slaves, never numbered, p. 79

- Number of places of worship and attendants, p. 80

- Comparison of moral and educational efficiency of Separatists and Episcopalians, p. 81

- A Dissenter’s reasons for the non-payment of tithe, p. 83

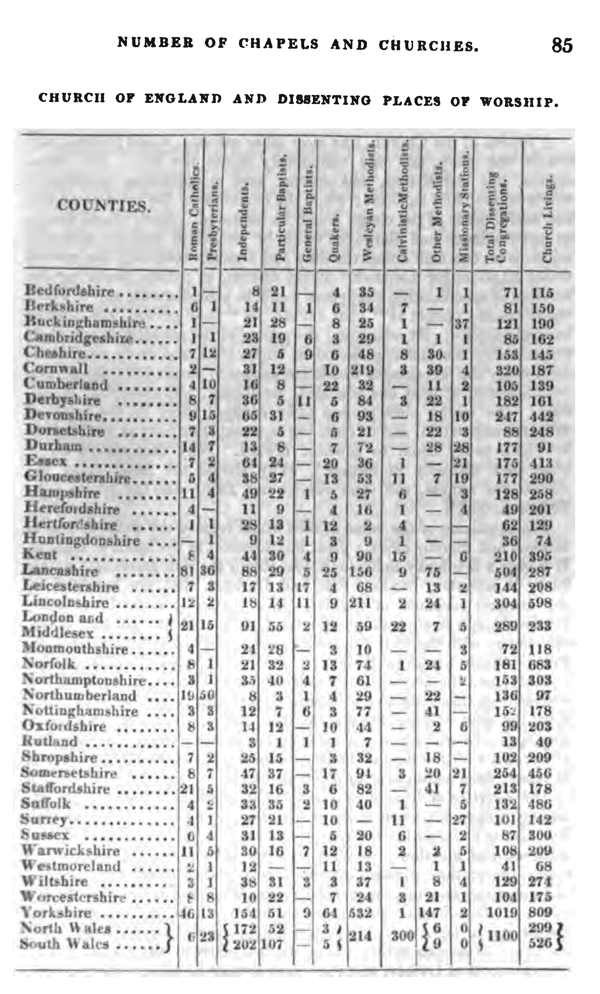

- Tabular statement of religious denominations in England, p. 85

- VIII.—who would be benefited by ecclesiastical reform?

- Church reform benefit the many and injure a few, p. 86

- Unfitness of the Clergy for secular functions, p. 86

- Unequal extent of benefices, p. 87

- Tithes should be commuted for an equivalent assessment on landlords 88

- Opinions of Lord Brougham, Burke, Watson, and Paley, on tithes 89

- Rights of lay-impropriators examined, p. 91

- Ought compensation to be allowed for Church Patronage?, p. 91

- Necessity of religious worship of some kind, p. 92

- Scotch example of church reformation, p. 93

- Example of Dissenters and Americans, p. 94

- Puerile attempts of the Bishops to save the church, p. 95

- I.—origin and tenure of church property.

- CHAPTER II.

- Alphabetic List of Bishops, Dignitaries, and Pluralists of the Church of England, p. 96

- Valuation of Sees and Dignities in the King’s Book, p. 131

- CHAPTER III. CHURCH OF IRELAND.

- Ireland, an illustration of Oligarchical government, p. 138

- A more revolting spectacle of ecclesiastical abuse than England, p. 139

- Irish proprietary mistake their true policy, p. 139

- Extent of acres appertaining to the Irish sees, p. 140

- Wealth bequeathed to their families by the bishops, p. 142

- Biographical notice of the late bishop Warburton, p. 143

- Injurious tendency of Act for composition of tithes, p. 144

- Pluralities, unions, and extent of benefices, p. 145

- Statement of sums to be paid in lieu of tithes in several parishes, the names of incumbents and patrons, p. 148

- Return of parishes which have compounded, and total amount of lay and clerical tithes, p. 152

- Ministers’ money and church fees, p. 153

- Estimate of the revenues of the Protestant establishment, p. 154

- Number of clergy among whom the revenues are divided, p. 154

- Constitution of the Deans and Collegiate Chapters, p. 155

- Eight hundred and fifty individuals possess 3195 ecclesiastical offices, p. 157

- Tabular statement of church patronage, p. 158

- Non-residence of bishops and parochial clergy, p. 160

- Oppressiveness of the Tithe System illustrated, p. 163

- Appointment of tithe committee in the House of Lords, p. 164

- Proportion of Roman Catholics and Protestants, p. 166

- State stipends paid to Dissenters—origin of Regium Donum, p. 169

- Management of the first fruits fund, p. 170

- Return of promotions in the Irish church, p. 172

- Intolerance of the church towards Dissenters and Catholics, p. 176

- Crisis of the Irish church at the close of 1831, p. 179

- General conclusions on the United Church of England and Ireland 182

- CHAPTER IV. REVENUES OF THE CROWN.

- Delusion practised in respect of the crown revenues, p. 184

- Origin and history of the crown lands, p. 186

- Abuses in the management of the landed revenues, p. 189

- Amount and appropriation of landed revenues, p. 192

- Expenditure on Regent-street, Charing-cross, Windsor Castle, &c. 193

- Pickings from palace jobs, p. 193

- Official statement of income and expenditure of landed revenues, p. 194

- Estimate of the value of crown lands, p. 195

- Sale of them recommended, p. 196

- Droits of the crown and admiralty, p. 197

- Origin of and examples of application of produce of admiralty droits, p. 197

- Four-and-a-half per cent. Leeward Island duties, p. 202

- Expended in parliamentary jobbing—Burke’s pension, p. 203

- Curious expedient of Tory ministers for raising a jobbing fund, p. 205

- West-India church establishment, p. 205

- Scotch hereditary revenues, p. 207

- Gibraltar duties—duchies of Cornwall—escheats—fines—and penalties, p. 208

- Statement of produce of hereditary revenues of the crown, p. 210

- CHAPTER V. CIVIL LIST.

- King’s household—its Gothic origin—and expensive establishment 212

- Departments of the lord chamberlain, lord steward, and master of the horse, p. 213

- Origin of the privy-purse and court pension-list, p. 215

- Publication of the court pension-list, p. 216

- Civil list allowance augmented a quarter of a million in 1820, p. 217

- Civil lists of George III. and George IV. 218

- Settlement of civil list of William IV. 219

- Remarks on the Whig civil list, p. 221

- Royal debts and expenditure during the two last reigns, p. 221

- Total expenditure from accession of Geo. III. to the death of Geo. IV. one hundred millions, p. 225

- The King exempt from taxes—a court and levee, p. 266

- Policy and character of the two late reigns, p. 228

- Peculiar death of Geo. IV. and his chief counsellors, p. 234

- Civil list accounts, p. 235

- Return of the incomes of the royal family, p. 237

- Expenditure on Windsor Castle and Buckingham Palace, p. 238

- Ancient payments out of English, Scotch, and Irish civil lists, with illustrative notes, p. 239

- CHAPTER VI. PRIVY COUNCIL—DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS—AND CONSULAR ESTABLISHMENTS.

- Number and constitution of the king’s privy council, p. 244

- Sir James Graham’s motion on the emoluments of privy counsellors 245

- Ambassadors and diplomatic missions, p. 247

- Consular establishments, p. 250

- Official returns relative to foreign ministers and consuls, p. 251

- Salaries and allowances as fixed by the Whig ministry, p. 252

- CHAPTER VII. THE ARISTOCRACY.

- Triumphs of knowledge over feudal barbarisms, p. 254

- Clergy, lords, and commons deviated from original objects of their institution, p. 256

- Tendency of right of primogeniture and entails, p. 258

- Objectionable privileges of the peerage, p. 260

- Injustice of aristocratic taxation, p. 262

- Incomes of landed interest, the legitimate fund for taxation, p. 265

- Specimen of partial exemptions from taxes, p. 266

- Aristocratic game laws—a specimen of late tyranny of the Boroughmongers, p. 268

- Incomes of the aristocracy, p. 271

- Anti-property theories of Robert Owen and St. Simon, p. 272

- Diminutive income of the Peerage compared with that of other classes, p. 275

- Different classes of society and their respective incomes, p. 277

- Taxes levied on the industrious orders, p. 278

- Increase of the peerage, p. 281

- More prolific than other classes of the community, p. 281

- Influence of Toryism of late reigns on character of the Peerage, p. 282

- Votes of the lords on Reform Bill, p. 283

- Absurdity of hereditary legislation, p. 283

- Sources of aristocratic monopoly and abuse, p. 284

- CHAPTER VIII. LAW AND COURTS OF LAW.

- Boasted independence of the Judges considered, p. 286

- Confused state of statute and common law, p. 287

- Judges do not understand the law, though the people are expected to comprehend it, p. 288

- Dunning’s mode of expounding acts of parliaments, p. 289

- A lawyer’s library described, p. 290

- Causes of the multiplication of statutes, p. 291

- Obscure language in which they are drawn—example from sir R. Peel’s acts, p. 293

- Hodge-podge acts—blunder in the forgery act of sir J. Scarlett, p. 295

- Legislation, an after-dinner amusement of the house of commons 296

- Number and emoluments of the professional classes, p. 297

- Debtor laws chief source of litigation and legal emoluments, p. 299

- Courts of request, &c. encourage a vicious system of credit, p. 301

- Summary of Legal Abuses and Defects:

- Objections against a stipendiary magistracy, p. 303

- Different laws in different places, p. 304

- Different laws for different persons, p. 305

- Absurdities of fines and recoveries, p. 307

- Defects in agreements for leases and conveyances, p. 308

- Arrest for debt—its injustice, p. 308

- Inconsistent liabilities of property for debt, p. 309

- Insecurity of titles to estates, p. 312

- Inconsistences of the marriage-laws, p. 312

- Monstrous costs of law-suits, p. 313

- Law of debtor and creditor, p. 315

- List of absurdities in judicial administration, p. 316

- Oppressions under the excise-laws, p. 321

- Prospects of legal reform, p. 325

- Official returns illustrative of law and courts of law, p. 329

- Working of the insolvent debtors’ act, p. 332

- CHAPTER IX. PROGRESS OF THE PUBLIC DEBT AND TAXES.

- Effects of taxes on wages and profits, p. 334

- Objects of the parliamentary wars waged since 1688, p. 335

- Short view of each reign, from the accession of William III. 336

- Increase of debt and taxes consequent on each war since the Revolution, p. 336

- Cost of war against independence of United States of America, p. 339

- Cost of the French war from 1793 to 1815, p. 340

- Conclusions on disastrous policy of the Borough-government, p. 342

- CHAPTER X. EXPOSITION OF THE FUNDING-SYSTEM.

- Feudal system had one advantage, p. 343

- Funds, exchequer-bills, and navy-bills explained, p. 344

- Progress and state of the Debt, to the year 1831, p. 346

- Annual charge entailed on the country by the war of 1793, p. 348

- Plans for redemption of the debt, p. 349

- Dead-weight-annuity project, p. 354

- New suggestions for liquidating the Debt, p. 356

- Catastrophe of the funding-system, p. 359

- Examination of question on violation of national faith, p. 360

- Severe distress consequent of an attack on the funds, p. 360

- A violation of national faith perpetuate the power of the Oligarchy 362

- The last resort of the Aristocracy, p. 363

- CHAPTER XI. TAXATION AND GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE.

- General principles of finance and taxation, p. 366

- Examples of the violation of these principles, p. 368

- Expense of public offices, p. 371

- The great “exchequer job”, p. 372

- Audit-office, p. 374

- Civil department of the army—Woolwich academy, p. 375

- Department of the navy and dock-yards, p. 376

- Increase in peace-establishments, p. 377

- Expenditure of the Colonies—utility of, p. 379

- Losses sustained by the colonial system, p. 381

- Factory system and slave-trade, p. 382

- Lord-lieutenant of Ireland, p. 383

- Coronation expenditure—absurdity of the pageant, p. 384

- II.—workings of taxation.

- Effect of monopolies in augmenting prices, p. 385

- Soap duties, p. 385

- Silk and hemp duties, p. 386

- Glass, paper, pamphlet, and advertisement duties, p. 386

- Sea policies, fire insurance, and stamp duties, p. 387

- Exemption of Ireland from taxation, p. 387

- Taxes on newspapers, and their influence on the press, p. 388

- The press, a fourth estate, p. 389

- Proposal to manage the public journals, p. 390

- Irresponsible power of the Times newspaper, p. 391

- Newspaper press not injured by abolition of stamp duties, p. 393

- Reduction in duties on like discovery of an useful invention, p. 393

- CHAPTER XII. THE EAST INDIA COMPANY.

- Political influence of Bank and East India Company, p. 394

- Origin and progress of the Company, p. 395

- Decennial settlement of lands in India, p. 398

- Indian wars and territorial acquisitions, p. 401

- Population and extent of the Anglo-Indian empire, p. 401

- Exploits of the Duke of Wellington in India, p. 404

- Government and patronage of India, p. 405

- Territorial revenues of India, p. 412

- Commercial intercourse with the Chinese, p. 413

- Commercial profits of the Company, p. 414

- People of England pay the Company’s dividend in the monopoly price of tea, p. 415

- Thoughts on the renewal of the Company’s charter, p. 418

- House list—treatment of “East Indians”—colonization—India-press, p. 420

- Rupture with the Chinese—Select Committee and Messrs. Lindsay & Co. 422

- The real point of interest between the Company and the people stated, p. 423

- Extravagant expenditure of Company and necessity of retrenchment, p. 424

- Facts relative to the India question, p. 425

- Accounts of the revenues and debts of the Company, p. 426

- Postscript on East India Company, p. 451

- CHAPTER XIII. THE BANK OF ENGLAND.

- A class of politicians with one idea, p. 428

- Mistaken views of political economists, p. 428

- Origin and progress of the Bank, p. 430

- Provisions of the Bank charter, p. 430

- Compelled to pay in shillings and sixpences, p. 431

- Issue notes of a low denomination, p. 432

- Contemporary increase of issues and government advances, p. 432

- Bank-restriction-act—legal tender—Lord King, p. 433

- Resumption of cash-payments in 1823, p. 435

- Mischiefs of irresponsible power of Bank over the circulation, p. 436

- Sources of Bank profits, and their enormous amount, p. 436

- Pitt and plunder system the chief source of Bank profits, p. 439

- Exclusive privileges of the Bank, p. 442

- Directors have not acted on sound principles of banking, p. 442

- Thoughts on a New Bank of England, p. 443

- Terms on which the Bank charter ought to be renewed, p. 444

- Dividends on Bank Stock, from establishment of Company, p. 445

- Return of persons convicted of forgery, p. 446

- Statement of affairs of the Bank, p. 447

- Annual sums payable to the Bank by the public, p. 448

- Account of distribution of profits among proprietors, p. 449

- Returns of circulation of notes in each year since 1792, p. 450

- Postscript on Bank and East India Company, p. 672

- CHAPTER XIV. MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS, COMPANIES, GUILDS, AND FRATERNITIES.

- Difficulty of fixing the public mind on a new subject, p. 452

- Corporations do not embody the interests of cities and towns, p. 453

- Origin of corporations, guilds, and fraternities, p. 454

- How popular constitution of corporate bodies destroyed, p. 455

- Customs and institutions of the ancient guilds, p. 456

- Rise and downfal of Merchant-Tailors Company of Bristol, p. 458

- Management and revenues of companies of the City of London, p. 460

- Oppressive and vexatious powers exercised by the City Companies 460

- corporations of cities and towns.

- Corporation of City of London, p. 464

- Corporation of Bristol, p. 467

- Corporation of Liverpool, p. 468

- Corporation of Bath, p. 469

- Corporation of Preston, p. 471

- Corporation of Lichfield, p. 471

- Corporation of Stafford, p. 472

- Corporation of Northampton, p. 472

- Corporation of Gloucester, p. 473

- Corporation of Leeds, p. 474

- Conduct of the corporations of Newcastle and Bristol, p. 474

- Suggestions for the reform of corporate bodies, p. 475

- Estate of the City of London, p. 476

- Dr. Brady’s interpretation of “communitatis”, p. 477

- CHAPTER XV. PLACES, PENSIONS, SINECURES, REVERSIONS, HALF-PAY, AND SUPERANNUATIONS.

- Progress through the recesses of the Oligarchy, p. 479

- Salaries and number of persons employed in the public offices, p. 480

- One million per annum might be saved by reductions in salaries, p. 481

- Civil and military pluralities, p. 482

- Half-pay and superannuations, p. 482

- Sinecures, reversions, and pensions, p. 484

- Monstrous legal sinecures in courts of law, p. 485

- Pension-roll amounts to £805,022 per annum, p. 489

- Infamous pension-act of 57 Geo. III. 490

- Unjust principle of granting compensations, p. 491

- List of “high and efficient public men”, p. 492

- Pensions to ex-lord-chancellors and judges, p. 493

- Compensation and retired allowances, p. 493

- Pensions under bankruptcy court act, p. 494

- Salaries and pensions exceeding £1000, p. 497

- Classification of 965 placemen, receiving £2,161,927 per annum, p. 499

- Sumptuous pickings of lawyers, p. 499

- Conduct of lawyers in respect of court fees, p. 500

- Reductions of the Whig ministry, p. 500

- General statement of annual expenditure of the country in salaries, pensions, sinecures, &c. 502

- Principles on which government has been carried on by Tory administrations, p. 503

- CHAPTER XVI.

- Alphabetic list of placemen, pensioners, sinecurists, compensationists, and grantees., p. 505

- Addendum to Place and Pension list, p. 589

- CHAPTER XVII. HOUSE OF COMMONS, PAST, PRESENT, AND TO COME.

- i.—progress of the constitution up to the reform bill.

- Iniquities of the Borough System doomed, and need not further exposure, p. 591

- Progress of the constitution up to the Reform Bill, p. 592

- Condition of the people under the Saxons, p. 592

- Origin and influence of the Middle Orders, p. 593

- House of Commons began to exercise legislative functions only a short time anterior to the Civil Wars, p. 594

- Revolution of 1688 did not concede to the industrious orders their share of political power, p. 595

- Causes of public prosperity subsequent to the Revolution, p. 595

- Constitutional deductions, p. 597

- ii.—adequacy of the reform bill to the wants of the nation investigated.

- Two principles on which the Reform Bill is founded, p. 598

- Groundless fears of the Alarmists, p. 598

- Real objects sought by the people, p. 599

- Previous political changes not altered the status of the Aristocracy 599

- Absurd apprehensions about levelling doctrines, p. 600

- Principles which ought to determine the elective qualification, p. 601

- Universal suffrage, impracticability and mischievousness of, p. 603

- Ten-pound qualification not a property qualification, p. 605

- Comparative results of universal and household suffrage, p. 606

- iii.—practical results from the adoption of the reform bill.

- Constitutional changes valueless in themselves, p. 606

- When settled people cease to agitate questions of civil rights, p. 607

- Practical benefits from parliamentary reform enumerated, p. 608

- iv.—statistics of representation.

- Freeholders in England and Wales, p. 609

- Registered freeholders in Ireland, p. 610

- Population, electors, houses, &c. of the fifty-six boroughs disfranchised by the Reform Bill, p. ib.

- Population, electors, &c. of the thirty semi-disfranchised boroughs 611

- Population, houses, &c. of boroughs not disfranchised, p. 612

- Welsh boroughs, p. 614

- Population, houses, &c. of the proposed New Boroughs, p. 615

- Population, electors, &c. of the Scotch cities and burghs, p. 616

- Limits of the proposed New Boroughs, p. 617

- Number of parliaments held in each reign, p. 621

- List of ancient boroughs, p. 622

- Progress of representation in different reigns, p. 622

- v.—retrospective glance at past houses of commons. 623

- Analysis of the house of commons elected in 1830, p. 626

- i.—progress of the constitution up to the reform bill.

- APPENDIX.

- 1. Inns of Court and Chancery, p. 627

- 2. Trinity College, Dublin, p. 623

- 3. Return of cities and towns with a population exceeding 10,000, not included in the Reform Bill, p. 636

- 4. Expenditure of the army, navy, ordnance, &c. 637

- 5. Sums expended under the head of Civil Contingencies, p. 638

- 6. Returns of Army and Navy half-pay and retired allowances, p. 640

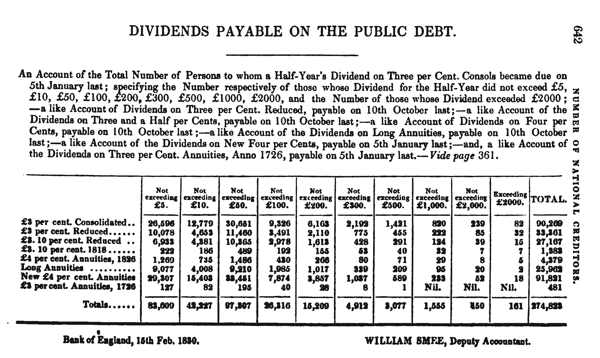

- 7. Number of public creditors and amount of their dividends, p. 642

- 8. Population, free and slaves, imports and exports of the Colonies, p. 643

- 9. House of Lords, origin and character of, p. 644

- 10. Borough lords and their Representatives, p. 646

- 11. Ecclesiastical Patronage of each of the Nobility, and the value of Rectories and Vicarages in their gift, p. 650

- 12. Return of the amount of church rates, county rates, and highway rates, &c. in each county of England and Wales, p. 668

- 13. Return of lay and clerical magistrates, p. 669

- 14. Commissioners of sewers, institution of, and abuses in their administration, p. 670

- 15. Progress of Population in Great Britain, p. 672

- 16. Postscript, p. 672

- Endnotes

[a]

“We must be free or die, who speak the tongue

Which Milton held. In everything we are sprung

That Shakspeare spake; the faith and morals hold

Of Earth’s first blood, have titles manifold._____”

Engraved for the Extraordinary Black Book from Originals by Percy Roberts.

published by, effingham wilson, royal exchange. london, 12th march, 1832.

[iii]

ADVERTISEMENT TO THE NEW EDITION.↩

The rapid sale of a large impression of The Black Book has speedily afforded an opportunity for again subjecting it to severe revision, and this it has undergone in every department. Besides improving the arrangement, the Lists of Places, Pensions, and Pluralists have been carefully corrected, and the illustrative notes revised. The reductions in salaries and allowances, the settlement of the Civil List, and other economical arrangements of Ministers, either actually effected, or in contemplation, have been noticed.

Besides correction, many parts have been greatly enlarged, as those on the Church, Legal Sinecures, the Bank of England, and East-India Company; in the former a section has been added on the Numbers, Wealth, and Educational Efficiency of the Dissenters; and in the last have been comprised the chief facts and considerations involved in the approaching renewal of the charters of these two powerful associations. In addition, several new chapters have been introduced on subjects of immediate national interest; one on the Origin and Present State of Corporations in Cities and Towns, and on Companies, Guilds and Fraternities: these form branches of the ancient institutions of the country, and an account of them was essential to the completeness of our work. A chapter has been added on the Principles of Finance, Abuses in the Government Expenditure, and the Workings of Taxation. Also a Précis of the House of Commons, Past, Present, and to Come; with details illustrative of the Reform Bill, and the present state of parties and opinions.

[iv]

In the Appendix will be found many new articles and tables of value, as those on the Ecclesiastical Patronage of the Nobility—the House of Lords—Inns of Court—Church Rates—Trinity College—Colonial Statistics—Civil Contingencies—Remarks on the Reports on Irish Tithes—Commissioners of Sewers—Lay and Clerical Magistrates, &c.

Notwithstanding our anxiety to be correct, we cannot be sure that in every case we have succeeded. Our work is an assemblage of facts and principles, and it would be wonderful, if, in so great a number, some errors had not escaped vigilance. Of errors of intention we know we are guiltless; of those which have originated in the inaccuracy of the official returns and other sources of information on which we have relied, we cannot be so confident.

All parliamentary and public documents, whatever could throw light on the Ecclesiastical Establishments, the Civil List and Hereditary Revenues, the Courts of Law and Judicial Administration, the Aristocracy, Public Offices, Funding System, Public Revenue, Pensions, Sinecures, and other departments of our work, have been consulted. Our object has been an honest one, and we have sought to attain it by honest means: nothing has been exaggerated, nor has a single fact been wilfully misstated; we needed not the aid of falsehood, our case being strong enough without it, and we refer to the references on our pages to attest the veracity of our sources of intelligence. The statements we have made we shall at all times be ready to defend, but cannot answer for those which have been mistakenly imputed to us. It has unfortunately happened, either from similarity of name or other circumstance, many representations have been placed to our account with which we had nothing in common, and of which any one might be convinced by reference to our publication. In a high quarter we have been most unjustly aspersed: we believe it was unintentional; but, consistently with honour, atonement ought to have been [v] made by open acknowledgement in the same place where the injury was inflicted. Instead of exaggeration we have leaned to an opposite course; whenever we had doubts, from the absence of authentic information, about the correctness of a statement, we omitted it altogether: if, in the statements of the emoluments of individuals, the errors on the side of redundancy were compared with those of deficiency, we know—and many names inscribed on our pages know too—which would preponderate. These, however, are the evils of a day, while the good we have done will be lasting. By the improvement of the Game Laws the Aristocracy have torn out one leaf from our pages; when, in like manner, they have torn out the rest, our labours will cease—and not till then.

The Black Book is the Encyclopedia of English politics for the Georgian era, and will last as long as the abuses it exposes shall endure. It was, originally, brought out in periodical numbers twelve years ago, and laboured under the disadvantages incident to that mode of publication. Defective as the publication was, it excited unusual interest; though ill-arranged, rough in manner, and incorrect in matter, it contained a striking development of Oligarchical abuse, and thus fixed the attention of the public. It was oftentimes reprinted, and upwards of 14,000 copies were sold, almost without the expense of advertisement, or any of those helps from literary notices which are usually deemed essential to give celebrity to the productions of the press. In the edition of last year an endeavour was made to remedy the defects of the first undertaking; in this we flatter ourselves the task has been nearly completed.

The object of the Editor at first was, and now has been, to show the manifold abuses of an unjust and oppressive system; to show the dire calamities it has inflicted on the country, and by what ramifications of influence it has been supported.

Government has been a corporation, and had the same interests and the same principles of action as monopolists. It [vi] has been supported by other corporations; the Church has been one, the Agriculturists another; the Boroughs a third, the East-India Company a fourth, and the Bank of England a fifth: all these, and interests like these, constituted the citadel and out-works of its strength, and the first object of each has been to shun investigation. We have, however, rent the vail; those who before doubted may, if they please, come and see, and be convinced.

In lieu of the old system we are told a new one is in progress of being substituted; intelligence, not patronage, is to form the pivot of public authority: the idea is a grand one,—it is worthy of the age, and we wait in hope to see it practically realized.

In conclusion we must observe that many opinions have been introduced, from which, we doubt not, our readers will dissent; we regret this, but it is unavoidable. Our object has been Truth, not to compromise with error, nor knowingly pander to any prejudice, aristocratic or democratic. We have an aversion to war, foreign and domestic; nor do we love spoliation either on the part of the People or their Rulers. The land is full of miseries; we share them not, neither do we profit by them; but it is the impulse of our nature to wish to see them alleviated. In place of a bad government we wish a good one substituted; for it is not individuals, but the power of the State, directed by intelligence, which must administer to the maladies of a nation. And even wisdom and good intentions, without co-operation on the part of the community, would be unavailing. Public disorders of long standing and extremely complicated require deliberation as well as remedial applications. But while we crave indulgence for an Administration we believe patriotic, it must be an indulgence accompanied with constant watchfulness, and even suspicion, on the part of the People.

March 16th, 1832.

[vii]

ADDRESS TO THE NEW EDITION.↩

In our Dedication, written about a twelvemonth since, we expressed a want of confidence in the Whig Ministry. In the interval they have gained on our esteem. They mean well, but the difficulties they have to surmount are great. Arrayed against them are all the interests identified with public abuses, and which have so long flourished by the ruin of the country; but they must be compelled to yield. The People are quiescent; it is the quiescence of hope: should doubt prevail, they will rise in their might and scatter the band—the factious band that would interpose its selfish ends between the weal of twenty-four millions of persons.

The People have nobly done their duty, and Ministers must do [viii] theirs. In the words of their chief, they are individually pledged to the Reform Bill; it is the tenure of administration. They know their power; and to have held office so long without the means and determination to accomplish the public wish, would have been basely perfidious,—it would have been treachery to the nation. Their honour is bound up in the Bill—our patriotic Monarch is faithful—the People are unanimous—and it must be carried in all its integrity. Every interest in the empire is abased, shaken, or powerless, except that of Reform, and it must triumph: it is essential to the harmony of the Constitution and the peace of the community.

Hitherto, in their domestic policy, Ministers have claims on the confidence of the public. In Ireland they have endeavoured to substitute national interests and toleration, for the reign of factions and religious feuds. They have not fomented plots, nor sought by new laws to abridge popular liberties. They have entered on the Augean stable of judicial abuses. They have cut down a part of our enormous establishments; they have even touched their own salaries, and meditate further reductions. In the work of economy has consisted their greatest difficulty; it tends to generate opposition and discontent among those who ought to be their servants, and, by impairing future prospects, dilutes the zeal of mercenary supporters; but it has conciliated the esteem of the People.

[ix]

Abroad they have maintained peace and leaned to the side of constitutional governments. The battle of continental freedom is not yet won. A terrible phalanx is couched in the North and East, which waits only the acquiescence or neutrality of this country to open a new crusade against liberal institutions. While England and France are united, the hordes of Tyrants will not break from their ambush. Englishmen are awake! Feudal pretexts of national rivalry and hereditary hate will not excite hostile feelings towards a nation with which so many interests in common ought to unite them in amicable bonds. They rightly appreciate the Aberdeen school of foreign politics; they will not again suffer the produce of industry to be squandered and future calamities entailed in support of aristocratic wars,—in support of wars to defend Misrule at home and Despotism abroad!

So long as Ministers pursue national objects, they will be supported. They have opposed to them only that delinquent Muster-roll with whose names are associated every lavish grant—every attack on public liberty—every insolence of authority for the last forty years. That they should be vanquished by a set like this, when supported by the People, is impossible. While, however, we seek for them popular aid, it is, we repeat, an aid accompanied with unceasing vigilance. Government is [x] power, and its agents will luxuriate in the enjoyment without strict responsibility. Its inherent tendency is to abuse, not to improvement. Individuals are slow to reform without imperative motives; governments are still more reluctant: they are always prompt to bequeath the redemption of their follies to their successors; while posterity has cause to lament that justice has not been contemporary with guilt.

March 17th, 1832.

[xi]

DEDICATION TO THE PEOPLE.↩

To the People our labours may be fitly inscribed—they are the tribunal of last resort,—also the victims of Misrule,—and to them, therefore, may be properly dedicated a record of the abuses from which they have long suffered, and of the means by which they may be alleviated.

All the blessings the nation ought to enjoy have been intercepted,—the rewards of industry, science, and virtue have been dissipated in iniquitous wars abroad—at home, in useless establishments, in Oligarchical luxury, folly, and profusion.

If we wanted proof of misgovernment—of incapacity and turpitude—Ireland affords a frightful example: it is not Mr. O’Connell who causes her agitation; he is only one of the fruits of Tyranny,—an effect, not the cause, of the disorders, which have originated in the neglect of her vast resources, in an unemployed population, an absentee proprietary, and a plundering church. To the wretchedness of Ireland, England is fast approaching, and [xii] just as little from the efforts of individual disturbers. It is not the manufacturing, but the agricultural districts which are now excited; these have always formed the exclusive domain of the Clergy and Aristocracy;—the rural population is exactly what tithes, game-laws, the country magistracy, Church-of-Englandism, and a luxurious and non-resident priesthood have made them. And what do we behold? The people have risen against their pastors and landlords, and have resorted to nightly outrage and revenge—the last resort of the oppressed for wrongs for which neither remedy nor inquiry has been vouchsafed.

We are not of the number of those who inculcate patient submission to undeserved oppression. A favourite toast of Dr. Johnson was, “Success to an insurrection of the Blacks!” Shall we say—Success to the rising of the Whites! We should at once answer yes, did we not think some measures would be speedily adopted to mitigate the bitter privations and avert the further degradation of the labouring classes.

A new era, we are told, is about to commence:—no more liberticide wars—no more squanderings of the produce of industry in sinecures and pensions—and, above all, reform is to be conceded. We wait in patience. Our diseases are manifold and require many remedies, but the last is the initiative of all the rest, involving at once the destruction of partial interests—of monopolies, corn-laws, judicial abuse, unequal taxation,—and giving full weight and expression to the general weal and intelligence. If Ministers are honest, they deserve and will require all the support the People can give them to overturn a system which is the reverse: if they are not, they will be soon passed under the ban of their predecessors, with the additional [xiii] infamy of having deceived by pledges which they never meant to redeem. We have hope, but no confidence.

Public opinion, and not Parliament, is omnipotent; it is that which has effected all the good which has been accomplished, and it is that alone which must effect the remainder. Unfortunately, Government can never be better constituted than it is for the profit of those who share in its administration; they have no interest in change, and their great maxims of rule are,—first, to concede nothing, so long as it can with safety be refused; secondly, to concede as little as possible; and, lastly, only to concede that little when every pretext for delay and postponement has been exhausted. Such are the arcana of those from whom reform is to proceed, and it is unnecessary to suggest the watchfulness, unanimity, and demonstrations by which they must be opposed.

Some of the Ministers are honest—they are all ingenious, and, no doubt, will have an ingenious plan, with many ingenious arguments for its support, concocted for our acceptance,—a plan with many convolutions, cycles, and epicycles—and, perhaps, endeavour to substitute the shadow for the substance! But it will avail them nothing; the balance is deranged, and it must be adjusted by a real increase of democratic power. The remedy, too, must be one of immediate action, not of gradual incorporation; it must not be patch-work—no disfranchising of non-resident voters—the transfer of the right of voting to great towns—the lessening of election expenses—and stuff of that sort. Such tinkering will not merit discussion, and would leave the grievance precisely in its original state.

[xiv]

We have fully stated our views on the subject in the concluding article of our work: by their accomplishment a real reform would be obtained, and all good would follow in their train. Our last wishes are, that the People, to whom we dedicate our labours, will be firm—united—and persevering; and, rely upon it, we are on the eve of as great a social regeneration as the destruction of Feudality, the abasement of Popery, or any other of the memorable epochs which have signalized the progress of nations.

February 1st, 1831.

[xxxi]

ADDENDUM.↩

MINISTERIAL PLANS ON TITHES.

We thought of submitting some observations on the recent reports of the two Houses of Parliament on Irish tithes, and the resolutions founded upon them, but, in looking over what we have written, we find the subject has been nearly exhausted in our copious articles on the united churches of England and Ireland. If the project of Ministers for converting arrears of tithes in Ireland into debts of the crown, and levying them by government process, be enforced, it concedes at once the important principle in dispute as to the tenure of church property. If an evasion of tithes may be prosecuted by the attorney-general, like an evasion of the excise or revenue laws, then is the income of the church identified with the income of the State, and the clergy admitted to be the stipendiaries of the public. Nothing, however, we apprehend, will ultimately result from the government measure: these are not the times to harden the tithe laws, and convert what has been hitherto treated as a civil delinquency, when committed by a whole body of Christians, into a criminal charge when committed by an entire kingdom. Ministers in this, as other emergencies, will be compelled to succumb to events. Public opinion obviously points to two inevitable conclusions,—first, the abolition of the Irish protestant establishment as a national church; and, secondly, the appropriation of the tithes and ecclesiastical revenue to the wants of society, and not suffering the former to be amalgamated with the rents of the landlords.

The increasing numbers and wealth of Dissenters indicate that the fate of tithes in Ireland involves their fate in England. Such are the conflicting claims of religionists that in all measures of general improvement, whether as respects popular education or parliamentary reform, the Government is embarrassed rather than supported by its alliance with any; and we doubt not the question will soon arise whether it would not be better policy for the State to withdraw its support from the privileged worship, rather than be compelled to adopt the alternative, which will be speedily forced upon its consideration, of granting a common support both to separatists and members of the national church.

In these movements there is nothing to excite alarm; least of all in the prompt extinction of tithe. It is an impolitic and impoverishing impost condemned by Mr. Pitt and every statesman of eminence, and the only miracle is that it has been so long upheld. The attempt to confound rent with tithe is monstrous. One is as much private property as the wages of the operative, and every one, rich or poor, is alike interested in maintaining its inviolability. The difference between them [xxxii] is almost as great as that between useful industry and downright robbery; or the sinecure of lord Ellenborough and the salary of an efficient servant of the public.

The most difficult part of the question is the settlement of existing interests. A substantial difference has always appeared to us to subsist between the claims of the clerical and lay-tithe owner, and we have expressed as much on a former occasion (p. 91). Beyond a life interest we imagine no one would claim a compensation for the clergy, and even for this it would be fair to accept a compromise. It is a plain case of bankruptcy, and in lieu of receiving the full value they must be content with a dividend. If such is their lot, they will not be alone in misfortune. What a sinking in the condition of most classes at this moment, and how many fortunes have been cut from under the possessors within the last twenty years! What fluctuations have been wrought by changes in the currency, the introduction of machinery, and improvements in mercantile law! The clergy cannot expect to be exempt from the vicissitudes of life. They ought, themselves, to practise the precepts of resignation it has been their duty to inculcate in others, and place their affections on treasures more enduring than temporal possessions.

If the occupation of the clergy be gone, it is their own fault, and they have only themselves to blame. Government has always been prompt to lend its aid to support the ecclesiastical establishment; but the days are past when the “arm of flesh” could be put forth to control the religious faith of a nation. The basis of the contract between Church and State is that the latter shall afford protection, on condition the former affords spiritual instruction, to the people. If, however, the people secede from the established communion, or if its ministers, from want of zeal—correct discipline—or soundness of doctrine—fail to make converts of the community over which they are the appointed pastors; why, then, it may be reasonably inferred that as the duties have ceased, or failed to be discharged, the stipends annexed to them ought to cease also; or, at least, the servants of the fallen or abandoned worship ought only to be paid temporary allowances—as was the case with the Catholic clergy at the Reformation—till such time as they can adjust themselves to the altered circumstances of society.

A consideration of a peculiar nature tends to augment the difficulties of this embarrassing subject, and the apprehensions naturally felt by many at the sinking state of the Irish protestant establishment. By the articles of Union the churches of the two kingdoms are united into one episcopal church, under the denomination of “the United Church of England and Ireland.” It was no doubt esteemed good policy in the framers of this great legislative measure to support the weakness of one church by the strength of the other; but in the existing circumstances of the two countries it is likely the English hierarchy will consider it true wisdom to imitate the example of a certain order of the creation, remarkable for prescience of coming calamites, and endeavour to scape from so perilous an alliance!

[1]

The Black Book: An Exposition of Abuses in Church and State, Courts of Law, Municipal Corporations, and Public Companies

CHAPTER I. CHURCH OF ENGLAND.↩

Religion and the institution of property, the pursuits of science, literature, and commerce have greatly benefited the human race. Christianity is peculiarly the worship of the people: among them it originated, and to the promotion of their welfare its precepts are especially directed. Under the influence of its dogmas the pride of man is rebuked, the prejudices of birth annihilated, and the equal claim to honour and enjoyment of the whole family of mankind impartially admitted.

Men of liberal principles have sometimes shown themselves hostile to the Gospel; forgetting, apparently, that it has been the handmaid of civilization, and that for a long time it mitigated, and, finally, greatly aided in breaking the yoke of feudality. They are shocked at the corruptions of the popular faith, and hastily confound its genuine principles with the intolerance of Bigotry, the oppression of tithes, the ostentation of prelacy, and the delinquencies of its inferior agents, who pervert a humble and consoling dispensation into an engine of pride, gain, and worldliness. In spite, however, of these adulterations, the most careless observer cannot deny the generally beneficial influence of the Christian doctrine, in promoting decorum and equality of civil rights, in spreading a spirit of peace, charity, and universal benevolence.

As education becomes more diffused, the ancillary power of the best of creeds will become less essential to the well-being of society. Religions have mostly had their origin in our depravity and ignorance; they have been the devices of man’s primitive legislators, who sought, by the creations of the imagination, to control the violence of his passions, and satisfy an urgent curiosity concerning the phenomena by which he is surrounded. But the progress of science and sound morals renders superfluous the arts of illusion; inventions, which are suited only to the nursery, or an imperfect civilization, are superseded; and men submitting to the guidance of reason instead of fear, the dominion of truth, unmixed with error, is established on the ruins of priestcraft.

[2]

Even now may be remarked the advance of society towards a more dignified and rational organization. The infallibility of popes, the divine right of kings, and the privileges of aristocracy, have lost their influence and authority: they once formed a sort of secular religion, and were among the many delusions by which mankind have been plundered and enslaved. Superstition, too, is gradually fading away by shades; and it is not improbable it may entirely vanish, ceasing to be an object of interest, further than as a singular trait in the moral history of the species. Formerly, all sects were bigots, ready to torture and destroy their fellow-creatures in the vain effort to enforce uniformity of belief; now, the fervour of all is so far attenuated, as to admit not only of dissent, but equality of claim to civil immunities. The next dilution in pious zeal is obvious. Universal toleration is the germ of indifference; and this last the forerunner of an entire oblivion of spiritual faith. Such appears the natural death of ecclesiastical power; it need not to be hastened by the rude and premature assaults of Infidelity, which only shock existing prejudices, without producing conviction: while the priesthood continue to aid the civil magistrate, their authority will be respected; but when, from the diffusion of science, new motives for the practice of virtue and the maintenance of social institutions are generally established, the utility of their functions will cease to be recognized.

Sensible men of all ages have treated with respect the established worship of the people. If so unfortunate as to disbelieve in its divine origin, they at least classed it among the useful institutions necessary to restrain the passions of the multitude. This was the predominant wisdom of the Roman government. Speaking of this great empire, in its most triumphant exaltation, Gibbon says, “The policy of the emperors and the senate, as far as it concerned religion, was happily seconded by the reflections of the enlightened, and by the habits of the superstitious part of their subjects. The various modes of worship which prevailed in the known world were all considered by the people as equally true; by the philosopher as equally false; and by the magistrate as equally useful. And thus toleration produced not only mutual indulgence, but even religious concord.” [*] Further on he continues, “Notwithstanding the fashionable irreligion which prevailed in the age of the Antonines, both the interests of priests and the credulity of the people were sufficiently respected. In their writings and conversation, the philosophers asserted the independent dignity of reason; but they resigned their actions to the command of law and custom. Viewing with a smile of pity the various errors of the vulgar, they diligently practised the ceremonies of their fathers, devoutly frequented the temple of the gods, and, sometimes condescending to act a part on the theatre of superstition, they concealed the sentiments of the atheist under the sacerdotal robes. Reasoners of such a temper were scarcely inclined to wrangle about their respective modes of faith or of worship. [3] It was indifferent to them what shape the folly of the multitude might choose to assume; and they approached with the same inward contempt and the same external reverence the altars of the Libyan, the Olympian, or the Capitoline Jupiter.”

Can it be supposed the statesmen and teachers of the nineteenth century are less adroit and sagacious than those of pagan Rome? Can it be supposed those whose minds have been enlightened by foreign travel, who have witnessed the conflict of opposite creeds, and who have escaped the mental bondage of cloisters and colleges in the freedom of general intercourse, are less penetrating than the magnates of the ancient world? Like them too, they will be equally politic in maintaining an outward respect for the errors of the vulgar. In the prevailing worship they recognize an useful auxiliary to civil government; prosecuting no one for dissent, it can as little offend the philosopher as politician; and the topics of all-absorbing interest it holds forth to every class, divert the vast majority from too intense a contemplation of sublunary misfortunes, or from the painful contrast of their privations with the usurpations and advantages of their superiors.

The policy of governing nations by enlightening the few and hoodwinking the many, is of very old standing. It is strongly inculcated by Machiavel in his Prince, and Dugald Stewart remarks, that public men of the present day mostly hold the double-doctrine; [*] that is, they have one set of principles which they openly profess in complacence to the multitude, and another, comprising their real sentiments, which they keep to themselves, or confide to intimate friends. The result of this sinister policy may be constantly remarked in the proceedings of legislative assemblies: in the discussion of questions bearing on the social interests, especially such as involve the principles of government, the theory of morals, or population, there is invariably maintained a conventional latitude, beyond which if any one trespass, it is deemed more creditable to his sincerity than understanding. It is only the vain and superficial who unreservedly assail popular opinions, and prophane with invective and ribaldry the sanctities of religion. Such rash controversialists are ignorant of the points d’appui upon which the welfare and harmony of society depend; and though it may happen that honour, philanthropy, or patriotism be sufficient guarantees for the discharge of social duties by some, there are others whose turpitude can only be restrained by the fear of Tyburn or Tartarus. Hence theological inquiries have lost much of their interest, and are, in fact, placed beyond the pale of discussion. The mysteries of religion are well understood by the intelligent of all classes; it is considered for the good of society that some should “believe and tremble,” while others enjoy, in private, the consciousness of superior light; and to those who impugn and to those who dogmatise in matters of faith, the same indulgence is extended as to well-meaning disputants, who utter, as new discoveries, commonplace or self-evident truths.

[4]

Having made these general observations on the utility of religion, considered as a civil institution for the government of mankind during a period of ignorance, we shall proceed to our more immediate object—an exposition of the Established Church of this country.

In our elucidations of this important inquiry, it is not our intention to interfere with the doctrines of the national religion. We have heard that there are more than one hundred different sects of Christians: so it would be highly presumptuous in mere laymen to decide which of these multifarious modes of worship is most consonant to the Scripture. A certain Protestant Archbishop said, “Popery was only a religion of knaves and fools;” therefore, let us hope the Church of England, to which the Right Reverend Prelate belonged, comprises the honest and enlightened. The main purpose of our inquiries, is not the dogmas, but the temporalities of the Church. To us the great possessions of the clergy have long appeared an immense waste, which wanted surveying and enclosing, if not by act of parliament, by the act of the people. Like some of our political institutions, the excellence of our religious establishment has been greatly over-rated; it has been described as the most perfect in Europe; yet we are acquainted with none in which abuses are more prevalent, in which there is so little real piety, and in which the support of public worship is so vexatious and oppressive to the community.

Most countries on the Continent have reformed their church establishments: wherever a large property had accumulated in the hands of the clergy, such property has been applied to the service of the nation; and we are now the only people who have a large mass of ecclesiastical wealth appropriated to the maintenance of an indolent and luxurious priesthood. Even in papal Rome the church property has been sold to pay the national debt; so that far more property belonging to the clergy is to be found in any part of England of equal extent than in the Roman state. The cardinals of Rome, the bishops, canons, abbotts, and abbesses, have no longer princely revenues. A cardinal who formerly had thousands has now only four or five hundred pounds a-year. Residence is strictly enforced, and no such thing as pluralities is known; the new proprietors of the Church estates live on them and improve them to the best advantage. In France, there has been a still greater ecclesiastical reformation. Before the Revolution the clergy formed one fifty-second part of the population. The total number of ecclesiastics, in 1789, was estimated at 460,000, and their revenues at £7,400,000. At present the total number of ecclesiastics of all ranks, Protestant and Catholic, is about 40,000, and their total incomes £1,460,000. [*] Throughout Germany and Italy there have been great reforms in spiritual matters; the property of the church has been sold or taxed for the use of the state, and the enormous incomes of the higher have been more equally shared among the lower order of the clergy. In the Netherlands, the charges for religion, which supply the wants of the [5] whole community, except those of a few Jews, do not, in the whole, exceed £252,000, or 10d. per head per annum, for a population of six millions. [*] Even in Spain, under the most weak and bigotted government, ecclesiastical reform has made progress. A large portion of the produce of tithe is annually appropriated to the exigences of the State, and the policy adopted of late has dispossessed the clergy of their wealth; and this body, formerly so influential, is now lightly esteemed, and very moderately endowed.

Wherever these reforms have been made, they have been productive of the most beneficial effects; they have been favourable to religion and morality, to the real interests of the people, and even to the interests of the great body of the clergy themselves; they have broken the power of an order of men at all times cruel and tyrannical, at all times opposed to reform, to the progress of knowledge, and the most salutary ameliorations; they have diffused a spirit of toleration among all classes, removed the restrictions imposed by selfish bigotry, and opened an impartial career to virtue and talent in all orders; they have spread plenty in the land by unfettering the efforts of capital and industry, paid the debts of nations, and converted the idle and vicious into useful citizens. Wherever these changes have been introduced, they have been gratefully received by the People, and well they might; for with such changes their happiness is identified, liberty and intelligence diffused.

To England, however, the spirit of ecclesiastical improvement has not yet extended; though usually foremost in reform, we are now behind all nations in our ecclesiastical establishment; though the Church of England is ostentatiously styled the reformed Church, it is, in truth, the most unreformed of all the churches. Popery, in temporal matters at least, is a more reformed religion than Church of Englandism. There is no state, however debased by superstition, where the clergy enjoy such prodigious wealth. The revenues of our priesthood exceed the public revenues of either Austria or Prussia. We complain of the poor-rates, of superannuation charges, of the army and navy, of overgrown salaries and enormous sinecures; but what are all these abuses, grievous as they are, to the abuses of our church establishment, to the sinecure wealth of the bishops, dignitaries, and aristocratical rectors and incumbents? It is said, and we believe truly, that the clergymen of the Church of England and Ireland receive, in the year, more money than the clergy of all the rest of the Christian world put together. The clergy of the United Church cost at least seven times more than the whole of the clergy of France, Catholic and Protestant, while in France there is a population of 32,000,000; whereas, of the 24,000,000 of people comprising the population of our islands, less than one-third, or 8,000,000, are hearers of the Established Religion.

Such a system, it is not possible, can endure. While reform and reduction are in progress in other departments, it is not likely the clergy [6] should remain in undisturbed enjoyment of their possessions. To protect them from inquiry, they have neither prescriptive right nor good works to plead. As a body they have not, latterly, been remarkable for their learning, nor some of them for exalted notions of morality. It would be unfair to judge any class from individual examples; but it is impossible to open the newspapers without being struck by the repeated details of clerical delinquency. When there is an instance of magisterial oppression, or flagrant offence, it is almost surprising if some father in God, some very reverend dean, or some other reverend and holy person, be not accused or suspected. In this respect they resemble the clergy of the Church of Rome before the Reformation. It is known that the catholic priesthood in the fourteenth century exceeded all other classes in the licentiousness of their lives, their oppression, and rapacity; it is known, too, that their vices arose from the immense wealth they enjoyed, and that this wealth was the ultimate cause of their downfal.

It is not to the credit of the established clergy, that their names have been associated with the most disastrous measures in the history of the country. To the latest period of the first war against American independence, they were, next to George III. its most obstinate supporters; out of the twenty-six English Bishops, Shipley was the only prelate who voted against the war-faction. [*] To the commencement and protracted duration of the French revolutionary war, they were mainly instrumental; till they sounded the ecclesiastical drum in every parish, there was no disposition to hostilities on the part of the people; it was only by the unfounded alarms they disseminated, respecting the security of property and social institutions, the contest was made popular. In this, too, the episcopal bench was pre-eminent. Watson was the only bishop who ventured to raise his voice against the French crusade, and he, finding his opposition to the court fixed him in the poorest see in the kingdom, in the latter part of his life appeared to waver in his integrity. In supporting measures for restraining the freedom of discussion, and for interdicting to different sects of religionists a free participation in civil immunities, they have mostly been foremost.

Uniformly in the exercise of legislative functions, our spiritual lawmakers have evinced a spirit hostile to improvement, whether political, judicial, or domestic, and shown a tenacious adherence to whatever is barbarous, oppressive, or demoralizing in our public administration. The African slave-trade was accompanied by so many circumstances of cruelty and injustice, that it might have been thought the Bishops would have been the most forward in their endeavours to effect its abolition. Yet the fact is quite the contrary. They constantly supported that infamous traffic, and so marked was their conduct in this respect, that Lord Eldon was led, on one occasion, to declare that the commerce in human bodies could not be so inconsistent with Christianity as some [7] had supposed, otherwise it would never have been so steadily supported by the right reverend prelates. The efforts of Sir Samuel Romilly and others to mitigate the severity of the Criminal Code never received any countenance or support from the Bishops. But the climax of their legislative turpitude consists in their conduct on the first introduction of the Reform Bill. Setting aside the political advantages likely to result from this great measure, one of its obvious consequences was the destruction of the shameless immoralities and gross perjuries committed in parliamentary elections. Yet the Heads of the Church, in their anti-reform speeches, never once adverted to this improvement; their fears appeared chiefly to centre on the ulterior changes in our institutions which might flow from the Bill, and which might involve a sacrifice of their inordinate emoluments, and under this apprehension they voted against the people and reform.

Public education is a subject that appears to have peculiar claims on the attention of the clergy; unless indeed, as instructors of the people, their functions are extremely unimportant, and certainly, in this world, do not entitle them to much remuneration. Yet this is a duty they have generally neglected. Had not a jealousy of the Dissenters roused them into activity, neither the Bell nor Lancaster plans of instruction would have been encouraged by them. A similar feeling appears to have actuated them in the foundation of King’s College, in which their object is not so much the diffusion of knowledge, as the maintenance of their influence, by setting up a rival establishment to the London University. In short, they have generally manifested either indifference or open hostility to the enlightenment of the people, and, in numerous instances of eleemosynary endowments, they have appropriated to their own use the funds bequeathed for popular tuition.

So little connexion is there between the instruction of the people and the Church establishment, that it may be stated as a general rule that the ignorance and degradation of the labouring classes throughout England are uniformly greatest where there are the most clergy, and that the people are most intelligent and independent where there are the fewest clergy. Norfolk and Suffolk, for instance, are pre-eminently parsons’ counties; Norfolk has 731 parishes, and Suffolk 510. Yet it has been publicly affirmed, by those well-informed on the subject, [*] that so far as instruction goes, the peasantry of these two counties are as ignorant as “Indian savages.” The same observation will apply to the southern and midland counties, which have been the chief scene of fires and popular tumults, and where the people have been debased by the maladministration of the poor-laws. Compare the state of these districts with that of the north of England, in which it is generally admitted the people are best instructed and most intelligent, and where, from the great extent of parishes, they can have little intercourse with the parsons. Cumberland has 104 parishes, Durham 75, Northumberland [8] 88, Westmoreland 32, Lancaster 70, West-Riding of Yorkshire 193, Chester 90. It appears that Norfolk alone has a great many more parsons than all these northern counties, containing about one-third of the population of the kingdom. In Lancashire there are only 70 parsons for a million and a half of people; yet so little detriment have they suffered from the paucity of endowed pastors, that barristers generally consider the intelligence of a Lancashire common jury equal to that of a special jury of most counties.

A feeling of charity is the great beauty of Christianity; it is, indeed, the essence of all virtue, for, if real, it imports a sympathy with the privations of others divested of selfish considerations. The rich and prosperous do not need this commiseration; if they are not happy, it is their own fault, resulting from their artificial desires and ill-regulated passions. But the poor, without the means of comfortable subsistence, have scarcely a chance of happiness, though equally entitled with others to share in the enjoyments of life. It is the especial duty of the clergy to mitigate extreme inequalities in the lot of their fellow-creatures. Yet it is seldom their labours are directed to so truly a Christian object; though wallowing in wealth, a large portion of which is the produce of funds originally intended for the destitute and unfortunate, they manifest little sympathy in human wretchedness. As a proof of their ordinary callousness, it may be instanced that, at the numerous public meetings to relieve the severe distress of the Irish, in 1822, not a single Irish bishop attended, when it was notorious the immense sums abstracted by that class from the general produce of the country had been a prominent cause of the miseries of the people.

The clergy might be usefully employed in explaining to popular conviction the causes of the privations of the people, and in enforcing principles more conducive to their comfort and independence. In the agricultural districts, where their authority is least disputed, and where the sufferings of the inhabitants are greatest, such a course might be pursued under peculiar advantages. Their remissness in this respect is less excusable, since they are relieved from cares which formerly engaged anxious attention. In the time of Hoadley, Barrow, and Tillotson, much of the zeal and talent of the church was consumed in theological controversy: the removal of civil disqualifications has tended to assuage the fervour of ecclesiastical disputation, and the clergy have only tithes, not dogmas, to defend. This tendency to religious tranquillity has been also promoted by the indifference of the people, who discovered that little fruit was to be reaped from polemical disquisitions, which, like the researches of metaphysicians, tended to perplex rather than enlighten. Men now derive their religions as they do parochial settlements, either from their parents or birth-place, and seldom, in after life, question the creed, whether sectarian or orthodox, which has been implanted in infancy. The all-subduing influence of early credulity is proverbial. Once place a dogma in the catechism, and it becomes stereotyped for life, and is never again submitted to the ordeal of examination.

[9]

By education most have been misled,

So they believe because they so were bred;

The priest continues what the nurse began,

And thus the child imposes on the man!—Hind and Panther.

It is the inefficiency of the clergy as public teachers, the hurtful influence they have exerted on national affairs, and their inertness in the promotion of measures of general utility, that induce men to begrudge the immense revenue expended in their support, and dispose them to a reform in our ecclesiastical establishment. To the Church of England, in the abstract, we have no weighty objection to offer; and should be sorry to see her spiritual functions superseded by those of any other sect by which she is surrounded. Our dislike originates in her extreme oppressiveness on the people, and her unjust dealings towards the most deserving members of her own communion. To the enormous amount of her temporalities, and abuses in their administration, we particularly demur. It is unseemly, we think, and inconsistent with the very principles and purposes of Christianity, to contemplate lofty prelates with £20,000 or £40,000 a-year, elevated on thrones, living sumptuously in splendid palaces, attended by swarms of menials, gorgeously attired, and of priests to wait upon their persons, emulating the proudest nobles, and even taking precedence of them in all the follies of heraldry. Beneath them are crowds of sinecure dignitaries and incumbents, richly provided with worldly goods, the wealthiest not even obliged to reside among their flocks; and those who reside not compelled to do any one act of duty beyond providing and paying a miserable deputy just enough to keep him from starving. Contrasted with the preceding, is a vast body of poor laborious ministers, doing all the work, and receiving less than the pay of a common bricklayer or Irish hodman: but the whole assemblage, both rich and poor, paid so as to be a perpetual burthen upon the people, and to wage, of necessity, a ceaseless strife with those whom they ought to comfort, cherish, and instruct.

These are part of the abuses to which we object, and which we are about to expose; and as we intend our exposition to be complete, it may be proper to state the order in which the several subjects will be treated.

1. We shall inquire into the origin and tenure of Church-property, clearly showing that Church-property is public property, originally intended for, and now available to public uses.

2. We shall inquire into the tenure of patronial immunities; exhibit the present state of Church-patronage, and show, by examples, its abuses and perversion to political and family interests.

3. We shall expose the system of Pluralities, Non-residence, and other abuses in Church Discipline.

4. We shall treat on the enormous Revenues of the Established Clergy, from tithes, church-lands, surplice-fees, public charities, Easter-offerings, rents of pews, and other sources.

5. We shall detail some extraordinary examples of Clerical Rapacity, [10] exemplified in the conduct of the higher clergy, in regard to Queen Ann’s Bounty, and of the Clergy generally, as regards First Fruits, Moduses, and Tithes in London.

6. We shall advert to the history, origin, and defects of the Church Liturgy.

7. We shall compare the Numbers, Wealth, Moral and Educational efficiency of the Protestant Dissenters with the Established Clergy.