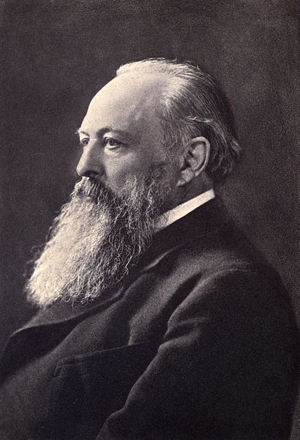

“Lord Acton” (John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton) (1834-1902) believed that historians should make moral judgements about the actions of the people they studied, in particular political and religious leaders. His best known statement of this view can be found in a series of letters he wrote to Bishop Creighton in 1887. They contain some of his most colorful language on the subject, such as his famous phrase, “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely”, as well as that historians should act like a “hanging judge” when it came time to judging the behaviour of such leaders.

The context of the letters was the question of how religious historians (Acton was a devout Catholic) should handle the corrupt and even criminal behaviour of many Popes, and the appalling treatment of dissidents and heretics during the Inquisition, such as censorship, banishment, imprisonment, torture, and brutal executions. This historical problem led Acton to talk about the universal nature of moral principles, their applicability to both rulers and those they ruled, the requirement for historians to use such principles in the assessment of historical figures, the tendency of these powerful historical figures to be “bad men”, and that it was the function of historians to “hang them”. In the third letter to Creighton, Acton quotes with some approval a conversation he had with John Bright, one of the leaders of the Anti-Corn Law League, who stated to him that “If the people knew what sort of men statesmen were, they would rise and hang the whole lot of them.” Whether Bright and Acton meant this literally or metaphorically is not clear.

Here is an extended quotation from one of these letters to Creighton:

Here, again, what I said is not in any way mysterious or esoteric. It appeals to no hidden code. It aims at no secret moral. It supposes nothing and implies nothing but what is universally current and familiar. It is the common, even the vulgar, code I appeal to.

Upon these two points we differ widely; still more widely with regard to the principle by which you undertake to judge men. You say that people in authority are not [to] be snubbed or sneezed at from our pinnacle of conscious rectitude. I really don’t know whether you exempt them because of their rank, or of their success and power, or of their date. The chronological plea may have some little value in a limited sphere of instances. It does not allow of our saying that such a man did not know right from wrong, unless we are able to say that he lived before Columbus, before Copernicus, and could not know right from wrong. It can scarcely apply to the centre of Christendom, 1500 after the birth of our Lord. That would imply that Christianity is a mere system of metaphysics, which borrowed some ethics from elsewhere. It is rather a system of ethics which borrowed its metaphysics elsewhere. Progress in ethics means a constant turning of white into black and burning what one has adored. There is little of that between St. John and the Victorian era.

But if we might discuss this point until we found that we nearly agreed, and if we do argue thoroughly about the impropriety of Carlylese denunciations, and Pharisaism in history, **I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope and King unlike other men, with a favourable presumption that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is the other way against holders of power, increasing as the power increases. Historic responsibility has to make up for the want of legal responsibility. Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men, even when they exercise influence and not authority: still more when you superadd the tendency or the certainty of corruption by authority. There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it. That is the point at which the negation of Catholicism and the negation of Liberalism meet and keep high festival, and the end learns to justify the means. You would hang a man of no position, like Ravaillac; but if what one hears is true, then Elizabeth asked the gaoler to murder Mary, and William III ordered his Scots minister to extirpate a clan. Here are the greater names coupled with the greater crimes. You would spare these criminals, for some mysterious reason. I would hang them, higher than Haman, for reasons of quite obvious justice; still more, still higher, for the sake of historical science.**

The standard having been lowered in consideration of date, is to be still further lowered out of deference to station. Whilst the heroes of history become examples of morality, the historians who praise them, Froude, Macaulay, Carlyle, become teachers of morality and honest men. Quite frankly, I think there is no greater error. The inflexible integrity of the moral code is, to me, the secret of the authority, the dignity, the utility of history. If we may debase the currency for the sake of genius, or success, or rank, or reputation, we may debase it for the sake of a man’s influence, of his religion, of his party, of the good cause which prospers by his credit and suffers by his disgrace. Then history ceases to be a science, an arbiter of controversy, a guide of the wanderer, the upholder of that moral standard which the powers of earth, and religion itself, tend constantly to depress. It serves where it ought to reign; and it serves the worst better than the purest.

Four years later, Acton would return to this topic in a lengthy introduction to a new edition of Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513) edited by Arthur Burd in 1891. I have put this Introduction online here. To make this essay easier to read I have put all his quotes in italics (he quotes works in Latin, French, German, Spanish, and Italian – as well as English), and have put in bold some of his comments and thoughts.

Whether one thinks Machiavelli wrote this notorious book in order to ingratiate himself with a ruthless Prince of his own day (the “ambitious” Machiavelli), or to warn, in a guarded fashion, readers of the true behavior of the ruthless leaders he observed around him (the “realist” or “republican Machiavelli), or as satire (the “comic” Machiavelli), Lord Acton respected Machiavelli’s “political sagacity”. He also thought that the practices he described had deep roots in European history which needed to be openly admitted and discussed by critical historians, and which were increasingly being adopted by politicians and leaders in his own day, especially in the nationalist movements in places like Italy and Germany.

Hidden among the thicket of untranslated quotations are many important observations about the nature of politics and the behavior of those who wield political power. Here are a selection:

- “that extraordinary objects cannot be accomplished under ordinary rules” – by this Acton/Machiavelli meant that many political feats, such as state building, empire and “nation” building, could not be achieved if politicians and “statesmen” were limited in their actions by normal moral precepts

- he chronicles a lengthy list of the kinds of actions politicians and religious leaders had taken to advance their interests, such as “murder by royal command”, and the violent suppression of “the rebel, the usurper, the heterodox or rebellious town”

- that these crimes had been improperly justified by historians and political theorists by a kind of moral relativism based on the ideas that “that public life is not an affair of morality, that there is no available rule of right and wrong, that men must be judged by their age, that the code shifts with the longitude, that the wisdom which governs the event is superior to our own”

- that it was wrong for these same theorists (such as nationalist historians or those who wrote hagiographic histories of kings and queens) to indulge in “the solecism of power” (the error of those who wield power) to only think about the glorious outcome (of say national unification) and to ignore the means taken to achieve that goal (war, revolution, oppression)

- Acton concluded that in order for these “extraordinary objects” to be achieved there had to be what he called “the emancipation of the State from the moral yoke” which was applicable to ordinary people

- the end result was what he termed “a Machiavellian restoration” which he saw taking place in late 19th century Europe, where there was “no righteousness apart from the State”, and where over the course of “our own” century we have “seen the course of its history twenty-five times diverted by actual or attempted crime”

Since Acton died soon after the start of the 20th century (as did other “old liberals” like Herbert Spencer and Gustave de Molinari) he did not live to see any of the atrocities states would inflict on the world in the bloody 20th century.