[Revised: 25 Apr. 2022]

[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

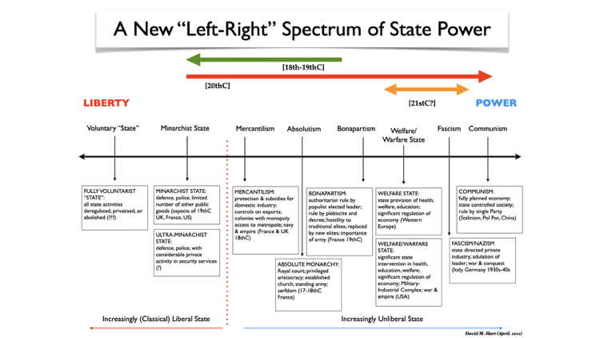

The degree to which classical liberals have upheld the principle that the state should not use (or at least minimise its use of) violence or coercion (the “non-aggression principle” (NAP)) is reflected in their attitudes about how powerful the state should be and what functions it is legitimate for it to engage in. Liberals have held a considerable range of views about what the proper functions of the state, should be. It is a topic which has divided liberals from the beginning, not to mention divided them from advocates of other political philosophies which support varying amounts of government coercion like conservatism, socialism, marxism, fascism, and other forms of government intervention in the economy (“interventionism”). Accordingly, we can assign all political points of view to a spectrum based upon their adherence to the NAP with one extreme being no limits to the power of the state to use (or initiate) aggression against individuals (“total power”) – what I term “the Right” – and the other being the strictest possible adherence to the NAP (or “total liberty”)- or what I term “the Left”. I have drawn up the following diagram to illustrate this version of the “political spectrum”:

[See a larger version of this image.]

It should be noted that the traditional “left-right spectrum” positions the total power of the communist state on “the left” and the nearly equally total power of the fascist/Nazi state of “the right”, which leaves the classical liberal state in the centre or the right of the centre. I think this way of distinguishing between different political philosophies and their different attitudes towards the use of state coercion (“power”) is misleading to say the least. In my “Liberty vs. Power” spectrum the ultra-minimal or severely limited state is at the far right, the total power of the communist state is at the far left, while the interventionist welfare state is to the left of the centre.

The reason for this is that historically “liberals” opposed the status quo of their day (for example, the absolutist state, or the mercantilist state”) and usually sat on the left hand-side of the speaker in the Chamber, while the defenders of the regime (the status quo) sat on the right of the Speaker. Thus it seems logical that, now that various forms of statism (such as the welfare state, the regulatory state, the warfare state) have become the new status quo, the opponents of these forms of interventionism should again be considered to be on “the left”.

Thus we have the following categories of more or less “statist” regimes situated on “the right”:

COMMUNISM: a fully planned economy; state controlled society; rule by single Party (Stalinism, Pol Pot, China)

FASCISM/NAZISM: state directed private industry; adulation of leader; war & conquest (Italy. Germany 1930s-40s

WELFARE STATE: state provision of health, welfare, education; significant regulation of economy (Western Europe, Australia)

WELFARE/WARFARE STATE: significant state intervention in health, education, welfare; significant regulation of economy; Military-Industrial Complex; war & empire (USA)

BONAPARTISM: authoritarian rule by populist elected leader; rule by plebiscite and decree; hostility to traditional elites; replaced by new elites; importance of army (France 19thC)

ABSOLUTE MONARCHY: Royal court; privileged aristocracy; established church; standing army; serfdom (17-18thC France)

MERCANTILISM: protection & subsidies for domestic industry; controls on exports; colonies with monopoly access to metropole; navy & empire (France & UK 18thC)

The coloured arrows in the table above show the historical movement beginning in the 18thC as liberal ideas began to have an impact. The policies of the mercantilist state in England and France were gradually reformed as a result of the influence of free trade ideas by theorists and activists such as Adam Smith and Richard Cobden in England and Jean-Baptiste Say and Frédéric Bastiat in France , so these countries began to move towards the “Liberty” end of the spectrum (the “left”). This progress was halted by the massive increase in state intervention which began during WW1 and which continued in the post-war period. Free trade and laissez-faire were abandoned and some nations turned to fascism (Italy and Germany) or communism (Russia, China). Thus the direction taken in the 20thC was towards the “Power” end of the spectrum (the “right”). After a brief flirtation with liberal reforms in the 1980s (Thatcher in Britain, Reagan in the US, David Longe in NZ) which shifted some countries to the Liberty end (the left), in the 21stC it seems we are headed back in the opposite direction once again.

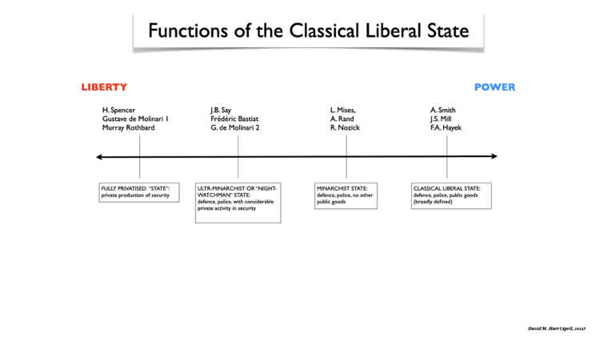

[See a larger version of this image.]

If we zoom into the “liberal” end of the political spectrum we can see some more detail about how different kinds of liberals have viewed the power of the state. Thus we can see the following:

CLASSICAL LIBERAL STATE: defence, police, public goods (broadly defined), education [A. Smith, J.S. Mill, F.A. Hayek]

MINARCHIST STATE: defence, police, no other public goods [L. Mises, A. Rand, R. Nozick]

ULTRA-MINARCHIST OR “NIGHT-WATCHMAN” STATE: defence, police, with considerable private or local provision of security [J.B. Say, Frédéric Bastiat, G. de Molinari 2 (older)]

FULLY PRIVATISED OR VOLUNTARIST “STATE”: private production of security, all state activities deregulated, privatised, or abolished [H. Spencer, Gustave de Molinari 1 (younger), Murray Rothbard]

Thus, to return to our distinction between “radical” liberals and “moderate” liberals, we can see that radical liberals have supported the “minarchist” or “ultra-minarchist” or even the “fully privatised” voluntary state; while moderate liberals have supported the “classical” functions of the state as articulated by Adam Smith for example.