ADAM SMITH,

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, vol. 1. (Cannan ed. 1904)

|

This is an e-Book from The Digital Library of Liberty & Power <davidmhart.com/liberty/Books> |

Source

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). 2 vols.

Editor's Note

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text, with links and back links to the main headings

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- margin notes have been "floated" right in order to remain within the 600px wide page of the eBook format

Contents of Volume I

- Preface p. v

- Editor’s Introduction p. page xiii

- Introduction and Plan of the Work p. 1

- BOOK I Of the Causes of Improvement in the productive Powers of Labour, and of the Order according to which its Produce is naturally distributed among the different Ranks of the People p. 5

- CHAP. I Of the Division of Labour p. ibid.

- CHAP. II Of the Principle which gives Occasion to the Division of Labour p. 15

- CHAP. III That the Division of Labour is limited by the Extent of the Market p. 19

- CHAP. IV Of the Origin and Use of Money p. 24

- CHAP. V Of the real and nominal Price of Commodities, or of their Price in Labour, and their Price in Money p. 32

- CHAP. VI Of the component Parts of the Price of Commodities p. 49

- CHAP. VII Of the natural and market Price of Commodities p. 57

- CHAP. VIII Of the Wages of Labour p. 66

- CHAP. IX Of the Profits of Stock p. 89

- CHAP. X Of Wages and Profit in the different Employments of Labour and Stock p. 101

- Part I. Inequalities arising from the Nature of the Employments themselves p. 102

- Part II. Inequalities occasioned by the Policy of Europe p. 120

- CHAP. XI Of the Rent of Land p. 145

- Part I. Of the Produce of Land which always affords Rent p. 147

- Part II. Of the Produce of Land which sometimes does, and sometimes does not, afford Rent p. 162

- Part III. Of the Variations in the Proportion between the respective Values of that Sort of Produce which always affords Rent, and of that which sometimes does and sometimes does not afford Rent p. 175

- Digression concerning the Variations in the Value of Silver during the Course of the Four last Centuries.

- First Period p. 177

- Second Period p. 191

- Third Period p. 192

- Variations in the Proportion between the respective Values of Gold and Silver p. 210

- Grounds of the Suspicion that the Value of Silver still continues to decrease p. 216

- Different Effects of the Progress of Improvement upon the real Price of three different Sorts of rude Produce p. ibid.

- First Sort p. 217

- Second Sort p. 219

- Third Sort p. 228

- Conclusion of the Digression concerning the Variations in the Value of Silver p. 237

- Effects of the Progress of Improvement upon the real Price of Manufactures p. 242

- Conclusion of the Chapter p. 247

- BOOK II Of the Nature, Accumulation, and Employment of Stock

- Introduction p. 258

- CHAP. I Of the Division of Stock p. 261

- CHAP. II Of Money considered as a particular Branch of the general Stock of the Society, or of the Expence of maintaining the National Capital p. 269

- CHAP. III Of the Accumulation of Capital, or of productive and unproductive Labour p. 313

- CHAP. IV Of Stock lent at Interest p. 332

- CHAP. V Of the different Employment of Capitals p. 340

- BOOK III Of the different Progress of Opulence in different Nations

- CHAP. I Of the Natural Progress of Opulence p. 355

- CHAP. II Of the Discouragement of Agriculture in the ancient State of Europe after the Fall of the Roman Empire p. 360

- CHAP. III Of the Rise and Progress of Cities and Towns, after the Fall of the Roman Empire p. 371

- CHAP. IV How the Commerce of the Towns contributed to the Improvement of the Country p. 382

- BOOK IV Of Systems of political Œconomy

- Introduction p. 395

- CHAP. I Of the Principle of the commercial, or mercantile System p. 396

- CHAP. II Of Restraints upon the Importation from foreign Countries of such Goods as can be produced at Home p. 418

- CHAP. III Of the extraordinary Restraints upon the Importation of Goods of almost all Kinds, from those Countries with which the Balance is supposed to be disadvantageous p. 437

- Part I. Of the Unreasonableness of those Restraints even upon the Principles of the Commercial System p. ibid.

- Digression concerning Banks of Deposit, particularly concerning that of Amsterdam p. 443

- Part II. Of the Unreasonableness of those extraordinary Restraints upon other Principles p. 452

- Endnotes to Volume I

[I-v]

PREFACE↩

THE text of the present edition is copied from that of the fifth, the last published before Adam Smith’s death. The fifth edition has been carefully collated with the first, and wherever the two were found to disagree the history of the alteration has been traced through the intermediate editions. With some half-dozen utterly insignificant exceptions such as a change of ‘these’ to ‘those,’ ‘towards’ to ‘toward,’ and several haphazard substitutions of ‘conveniences’ for ‘conveniencies,’ the results of this collation are all recorded in the footnotes, unless the difference between the editions is quite obviously and undoubtedly the consequence of mere misprints, such as ‘is’ for ‘it,’ ‘that’ for ‘than,’ ‘becase’ for ‘because’. Even undoubted misprints are recorded if, as often happens, they make a plausible misreading which has been copied in modern texts, or if they present any other feature of interest.

As it does not seem desirable to dress up an eighteenth century classic entirely in twentieth century costume, I have retained the spelling of the fifth edition and steadily refused to attempt to make it consistent with itself. The danger which would be incurred by doing so may be shown by the example of ‘Cromwel’. Few modern readers would hesitate to condemn this as a misprint, but it is, as a matter of fact, the spelling affected by Hume in his History, and was doubtless adopted from him by Adam Smith, though in the second of the two places where the name is mentioned inadvertence or the obstinacy of the printers allowed the usual ‘Cromwell’ to appear till the fourth edition was reached. I have been equally rigid in following the original in the matter of the use of capitals and italics, except that in deference to modern fashion I have allowed the initial words of paragraphs to appear [I-vi] in small letters instead of capitals, the chapter headings to be printed in capitals instead of italics, and the abbreviation ‘Chap.’ to be replaced by ‘Chapter’ in full. I have also allowed each chapter to begin on a fresh page, as the old practice of beginning a new chapter below the end of the preceding one is inconvenient to a student who desires to use the book for reference. The useless headline, ‘The Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,’ which appears at the top of every pair of pages in the original, has been replaced by a headline which changes with every chapter and, where possible, with every formal subdivision of a chapter, so that the reader who opens the book in the middle of a long chapter with several subdivisions may discover where he is immediately. The composition of these headlines has not always been an easy matter, and I hope that critics who are inclined to condemn any of them will take into account the smallness of the space available.

The numbers of the Book and Chapter given in the margin of the original are relegated, with the very necessary addition of the number of the Part of the chapter (if it is divided into numbered parts), to the top of the page in order to make room for a marginal summary of the text. In writing this summary I have felt like an architect commissioned to place a new building alongside some ancient masterpiece: I have endeavoured to avoid on the one hand an impertinent adoption of Smith’s words and style, and on the other an obtrusively modern phraseology which might contrast unpleasantly with the text.

The original index, with some slight unavoidable changes of typography, is reprinted as it appeared in the third, fourth and fifth editions, but I have added to it, in square brackets, a large number of new articles and references. I have endeavoured by these additions to make it absolutely complete in regard to names of places and persons, except that it seemed useless to include the names of kings and others when used merely to indicate dates, and altogether vain to hope to deal comprehensively with ‘Asia,’ ‘England,’ ‘Great Britain’ and ‘Europe’. I have inserted a few catchwords which may aid in the recovery of particularly striking passages, such as ‘Invisible hand,’ ‘Pots and pans,’ ‘Retaliation,’ ‘Shopkeepers, [I-vii] nation of’. I have not thought it desirable to add to the more general of the headings in the original index, such as ‘Commerce’ and ‘Labour,’ since these might easily be enlarged till they included nearly everything in the book. Authorities expressly referred to either in the text or the Author’s notes are included, but as it would have been inconvenient and confusing to add references to the Editor’s notes, I have appended a second index in which all the authorities referred to in the text, in the Author’s notes, and in the Editor’s notes are collected together. This will, I hope, be found useful by students of the history of economics.

The Author’s references to his footnotes are placed exactly where he placed them, though their situation is often somewhat curiously selected, and the footnotes themselves are printed exactly as in the fifth edition. The Editor’s notes and additions to Smith’s notes are in square brackets. Critics will probably complain of the trivial character of many of the notes which record the result of the collation of the editions, but I would point out that if I had not recorded all the differences, readers would have had to rely entirely on my expression of opinion that the unrecorded differences were of no interest. The evidence having been once collected at the expense of very considerable labour, it was surely better to put it on record, especially as these trivial notes, though numerous, if collected together would not occupy more than three or four pages of the present work. Moreover, as is shown in the Editor’s Introduction, the most trivial of the differences often throw interesting light upon Smith’s way of regarding and treating his work.

The other notes consist chiefly of references to sources of Adam Smith’s information. Where he quotes his authority by name, no difficulty ordinarily arises. Elsewhere there is often little doubt about the matter. The search for authorities has been greatly facilitated by the publication of Dr. Bonar’s Catalogue of the Library of Adam Smith in 1894, and of Adam Smith’s Lectures in 1896. The Catalogue tells us what books Smith had in his possession at his death, fourteen years after the Wealth of Nations was published, while the Lectures often enable us to say that a particular piece of information must have been taken from a book published before 1763. As it is known that Smith used the Advocates’ [I-viii] Library, the Catalogue of that library, of which Part II, was printed in 1776, has also been of some use. Of course a careful comparison of words and phrases often makes it certain that a particular statement must have come from a particular source. Nevertheless many of the references given must be regarded as indicating merely a possible source of information or inspiration. I have refrained from quoting or referring to parallel passages in other authors when it is impossible or improbable that Smith ever saw them. That many more references might be given by an editor gifted with omniscience I know better than any one. To discover a reference has often taken hours of labour: to fail to discover one has often taken days.

When Adam Smith misquotes or clearly misinterprets his authority, I note the fact, but I do not ordinarily profess to decide whether his authority is right or wrong. It is neither possible nor desirable to rewrite the history of nearly all economic institutions and a great many other institutions in the form of footnotes to the Wealth of Nations.

Nor have I thought well to criticise Adam Smith’s theories in the light of modern discussions. I would beseech any one who thinks that this ought to have been done to consider seriously what it would mean. Let him review the numerous portly volumes which modern inquiry has produced upon every one of the immense number of subjects treated by Adam Smith, and ask himself whether he really thinks the order of subjects in the Wealth of Nations a convenient one to adopt in an economic encyclopædia. The book is surely a classic of great historical interest which should not be overlaid by the opinions and criticisms of any subsequent moment—still less of any particular editor.

Much of the heavier work involved in preparing the present edition, especially the collation of the original editions, has been done by my friend Mrs. Norman Moor, without whose untiring assistance the book could not have been produced.

Numerous friends have given me the benefit of their knowledge of particular points, and my hearty thanks are due to them.

[I-ix]

[I-xiii]

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION↩

THE first edition of the Wealth of Nations was published on the 9th of March, [1] 1776, in two volumes quarto, of which the first, containing Books I., II. and III., has 510 pages of text, and the second, containing Books IV. and V., has 587. The title-page describes the author as ‘Adam Smith, LL.D. and F.R.S. Formerly Professor of Moral Philosophy in the University of Glasgow’. There is no preface or index. The whole of the Contents are printed at the beginning of the first volume. The price was £1 16s. [2]

The second edition appeared early in 1778, priced at £2 2s., [3] but differing little in appearance from its predecessor. Its pages very nearly correspond, and the only very obvious difference is that the Contents are now divided between the two volumes. There are, however, a vast number of small differences between the first and second editions. One of the least of these, the alteration of ‘late’ to ‘present,’ [4] draws our attention to the curious fact that writing at some time before the spring of 1776 Adam Smith thought it safe to refer to the American troubles as ‘the late disturbances’. [5] We cannot tell whether he thought the disturbances were actually over, or only that he might safely assume they would be over before the book was published. As ‘present disturbances’ also occurs close to ‘late disturbances,’ [6] we may perhaps conjecture that when correcting his proofs in the winter of 1775-6, he had altered his opinion and only allowed ‘late’ to stand by an oversight. A very large proportion of the alterations [I-xiv] are merely verbal, and made for the sake of greater elegance or propriety of diction, such as the frequent change from ‘tear and wear’ (which occurs also in Lectures, p. 208) to the more ordinary ‘wear and tear’. Most of the footnotes appear first in the second edition. A few corrections as to matters of fact are made, such as that in relation to the percentage of the tax on silver in Spanish America (vol. i., pp. 169, 170). Figures are corrected at vol. i., p. 327, and vol. ii., pp. 371, 374. New information is added here and there: an additional way of raising money by fictitious bills is described in the long note at vol. i., p. 294; the details from Sandi as to the introduction of the silk manufacture into Venice are added (vol. i., p. 379); so also are the accounts of the tax on servants in Holland (vol. ii., pp. 341-2), and the mention of an often forgotten but important quality of the land-tax, the possibility of reassessment within the parish (vol. ii., p. 329). There are some interesting alterations in the theory as to the emergence of profit and rent from primitive conditions, though Smith himself would probably be surprised at the importance which some modern inquirers attach to the points in question (vol. i., pp. 49-52). At vol. i., pp. 99, 100, the fallacious argument to prove that high profits raise prices more than high wages is entirely new, though the doctrine itself is asserted in another passage (vol. ii., p. 100). The insertion in the second edition of certain cross-references at vol. i., pp. 195, 311, which do not occur in the first edition, perhaps indicates that the Digressions on the Corn Laws and the Bank of Amsterdam were somewhat late additions to the scheme of the work. Beer is a necessary of life in one place and a luxury in another in the first edition, but is nowhere a necessary in the second (vol. i., p. 430; vol. ii., p. 355). The epigrammatic condemnation of the East India Company at vol. ii., p. 137, appears first in the second edition. At vol. ii., p. 284, we find ‘Christian’ substituted for ‘Roman Catholic,’ and the English puritans, who were ‘persecuted’ in the first edition, are only ‘restrained’ in the second (vol. ii., p. 90)—defections from the ultra-protestant standpoint perhaps due to the posthumous working of the influence of Hume upon his friend.

Between the second edition and the third, published at the end [I-xv] of 1784, [1] there are considerable differences. The third edition is in three volumes, octavo, the first running to the end of Book II., chapter ii., and the second from that point to the end of the chapter on Colonies, Book IV., chapter viii. The author by this time had overcome the reluctance he felt in 1778 to have his office in the customs added to his other distinctions [2] and consequently appears on the title-page as ‘Adam Smith, LL.D. and F.R.S. of London and Edinburgh: one of the commissioners of his Majesty’s Customs in Scotland; and formerly professor of Moral Philosophy in the University of Glasgow’. The imprint is ‘London: printed for A. Strahan; and T. Cadell, in the Strand’. This edition was sold at one guinea. [3] Prefixed to it is the following ‘Advertisement to the Third Edition’:—

‘The first Edition of the following Work was printed in the end of the year 1775, and in the beginning of the year 1776. Through the greater part of the Book, therefore, whenever the present state of things is mentioned, it is to be understood of the state they were in, either about that time, or at some earlier period, during the time I was employed in writing the Book. To this [4] third Edition, however, I have made several additions, particularly to the chapter upon Drawbacks, and to that upon Bounties; likewise a new chapter entitled, The Conclusion of the Mercantile System; and a new article to the chapter upon the expences of the sovereign. In all these additions, the present state of things means always the state in which they were during the year 1783 and the beginning of the present [5] year 1784.’

Comparing the second and the third editions we find that the additions to the third are considerable. As the Preface or ‘Advertisement’ just quoted remarks, the chapter entitled ‘Conclusion of the Mercantile System’ (vol. ii., pp. 141-60) is entirely new, and so is the section ‘Of the Public Works and Institutions which are necessary for facilitating particular Branches of Commerce’ (vol. ii., pp. 223-48). Certain passages in Book IV., chapter iii., on the absurdity of the restrictions on trade with France (vol. i., pp. 437-8 and 459-60), the three pages near the beginning of Book IV., chapter iv., upon the details of various drawbacks (vol. ii., pp. 2-5), the ten paragraphs on the herring fishery bounty (vol. ii., pp. 20-4) with the appendix on the same subject (pp. 435-7), and a portion of the discussion of the effects of the corn bounty (vol. ii., [I-xvi] pp. 10-11) also appear first in the third edition. With several other additions and corrections of smaller size these passages were printed separately in quarto under the title of ‘Additions and Corrections to the First and Second Editions of Dr. Adam Smith’s Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations’. [1] Writing to Cadell in December, 1782, Smith says:—

‘I hope in two or three months to send you up the second edition corrected in many places, with three or four very considerable additions, chiefly to the second volume. Among the rest is a short but, I flatter myself, a complete history of all the trading companies in Great Britain. These additions I mean not only to be inserted at their proper places into the new edition, but to be printed separately and to be sold for a shilling or half a crown to the purchasers of the old edition. The price must depend on the bulk of the additions when they are all written out.’ [2]

Besides the separately printed additions there are many minor alterations between the second and third editions, such as the complacent note on the adoption of the house tax (vol. ii., p. 328), the correction of the estimate of possible receipts from the turnpikes (vol. ii., p. 218, note ), and the reference to the expense of the American war (vol. ii., p. 409), but none of these is of much consequence. More important is the addition of the lengthy index surmounted by the rather quaint superscription ‘N.B. The Roman numerals refer to the Volume, and the figures to the Page’. We should not expect a man of Adam Smith’s character to make his own index, and we may be quite certain that he did not do so when we find the misprint ‘tallie’ in vol. ii., p. 320, reappearing in index ( s.v. Montauban) although ‘taille’ has also a place there. But the index is far from suggesting the work of an unintelligent back, and the fact that the ‘Ayr bank’ is named in it ( s.v. Banks), though nameless in the text, shows either that the index-maker had a certain knowledge of Scotch banking history or that Smith corrected his work in places. That Smith received a packet from Strahan ‘containing some part of the index’ on 17th November, 1784, we know from his letter to Cadell, published in the Economic Journal for September, 1898. Strahan had inquired whether the [I-xvii] index was to be printed in quarto along with the Additions and Corrections, and Smith reminded him that the numbers of the pages would all have to be altered to ‘accommodate them to either of the two former editions, of which the pages do not in many places correspond’. There is therefore no reason for not treating the index as an integral part of the book.

The fourth edition, published in 1786, is printed in the same style and with exactly the same pagination as the third. It reprints the advertisement to the third edition, altering, however, the phrase ‘this third Edition,’ into ‘the third Edition,’ and ‘the present year 1784’ into ‘the year 1784,’ and adds the following ‘Advertisement to the Fourth Edition’:—

‘In this fourth Edition I have made no alterations of any kind. I now, however, find myself at liberty to acknowledge my very great obligations to Mr. Henery Hop [1] of Amsterdam. To that Gentleman I owe the most distinct, as well as liberal information, concerning a very interesting and important subject, the Bank of Amsterdam; of which no printed account had ever appeared to me satisfactory, or even intelligible. The name of that Gentleman is so well known in Europe, the information which comes from him must do so much honour to whoever has been favoured with it, and my vanity is so much interested in making this acknowledgment, that I can no longer refuse myself the pleasure of prefixing this Advertisement to this new Edition of my Book.’

In spite of his statement that he had made no alterations of any kind, Smith either made or permitted a few trifling alterations between the third and fourth editions. The subjunctive is very frequently substituted for the indicative after ‘if,’ the phrase ‘if it was’ in particular being constantly altered to ‘if it were’. In the note at vol. i., p. 71, ‘late disturbances’ is substituted for ‘present disturbances’. The other differences are so trifling that they may be misreadings or unauthorised corrections of the printers.

The fifth edition, the last published in Smith’s lifetime and consequently the one from which the present edition has been copied, [I-xviii] is dated 1789. It is almost identical with the fourth, the only difference being that the misprints of the fourth edition are corrected in the fifth and a considerable number of fresh ones introduced, while several false concords—or concords regarded as false—are corrected (see vol. i., p. 108; vol. ii., pp. 215, 249). [1]

It is clear from the passage at vol. ii., p. 177, that Smith regarded the title ‘An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations’ as a synonym for ‘political œconomy,’ and it seems perhaps a little surprising that he did not call his book ‘ Political Œconomy ’ or ‘ Principles of Political Œconomy ’. But we must remember that the term was still in 1776 a very new one, and that it had been used in the title of Sir James Steuart’s great book, An Inquiry into the Principles of Political Œconomy: being an Essay on the Science of Domestic Policy in Free Nations, which was published in 1767. Nowadays, of course, no author has any special claim to exclusive use of the title. We should as soon think of claiming copyright for the title ‘Arithmetic’ or ‘Elements of Geology’ as for ‘Principles of Political Economy’. But in 1776 Adam Smith may well have refrained from using it simply because it had been used by Steuart nine years before, especially considering the fact that the Wealth of Nations was to be brought out by the publishers who had brought out Steuart’s book. [2]

From 1759 at the latest an early draft of what subsequently developed into the Wealth of Nations existed in the portion of Smith’s lectures on ‘Jurisprudence’ which he called ‘Police, Revenue and Arms,’ the rest of ‘Jurisprudence’ being ‘Justice’ and the ‘Laws of Nations.’ Jurisprudence he defined as ‘that science which inquires into the general principles which ought to [I-xix] be the foundation of the laws of all nations,’ or as ‘the theory of the general principles of law and government’. [1] In forecasting his lectures on the subject he told his students:—

‘The four great objects of law are justice, police, revenue and arms.

‘The object of justice is the security from injury, and it is the foundation of civil government.

‘The objects of police are the cheapness of commodities, public security, and cleanliness, if the two last were not too minute for a lecture of this kind. Under this head we will consider the opulence of a state.

‘It is likewise necessary that the magistrate who bestows his time and labour in the business of the state should be compensated for it. For this purpose and for defraying the expenses of government some fund must be raised. Hence the origin of revenue. The subject of consideration under this head will be the proper means of levying revenue, which must come from the people by taxes, duties, &c. In general, whatever revenue can be raised most insensibly from the people ought to be preferred, and in the sequel it is proposed to be shown how far the laws of Britain and other European nations are calculated for this purpose.

‘As the best police cannot give security unless the government can defend themselves from foreign injuries and attacks, the fourth thing appointed by law is for this purpose; and under this head will be shown the different species of arms with their advantages and disadvantages, the constitution of standing armies, militias, &c.

‘After these will be considered the laws of nations. . . .’ [2]

The connection of revenue and arms with the general principles of law and government is obvious enough, and no question arises as to the explanation on these heads given by the forecast. But to ‘consider the opulence of a state’ under the head of ‘police’ seems at first sight a little strange. For the explanation we turn to the beginning of the part of the lectures relating to Police.

‘Police is the second general division of jurisprudence. The name is French, and is originally derived from the Greek πολιτεία, which properly signified the policy of civil government, but now it only means the regulation of the inferior parts of government, viz.: cleanliness, security, and cheapness or plenty.’ [3]

That this definition of the French word was correct is well shown by the following passage from a book which is known to have [I-xx] been in Smith’s possession at his death, [1] Bielfeld’s Institutions politiques, 1760 (tom. i., p. 99).

‘Le premier Président du Harlay en recevant M. d’Argenson à la charge de lieutenant général de police de la ville de Paris, lui adressa ces paroles, qui méritent d’être remarquées: Le Roi, Monsieur, vous demande sûreté, netteté, bon-marché. En effet ces trois articles comprennent toute la police, qui forme le troisième grand objet de la politique pour l’intérieur de l’État.’

When we find that the chief of the Paris police in 1697 was expected to provide cheapness as well as security and cleanliness, we wonder less at the inclusion of ‘cheapness or plenty’ or the ‘opulence of a state’ in ‘jurisprudence’ or ‘the general principles of law and government’. ‘Cheapness is in fact the same thing with plenty,’ and ‘the consideration of cheapness or plenty’ is ‘the same thing’ as ‘the most proper way of securing wealth and abundance’. [2] If Adam Smith had been an old-fashioned believer in state control of trade and industry he would have described the most proper regulations for securing wealth and abundance, and there would have been nothing strange in this description coming under the ‘general principles of law and government’. The actual strangeness is simply the result of Smith’s negative attitude—of his belief that past and present regulations were for the most part purely mischievous.

The two items, cleanliness and security, he managed to dismiss very shortly: ‘the proper method of carrying dirt from the streets, and the execution of justice, so far as it regards regulations for preventing crimes or the method of keeping a city guard, though useful, are too mean to be considered in a general discourse of this kind’. [3] He only offered the observation that the establishment of arts and commerce brings about independency and so is the best police for preventing crimes. It gives the common people better wages, and ‘in consequence of this a general probity of manners takes place through the whole country. Nobody will be so mad as to expose himself upon the highway, when he can make better bread in an honest and industrious manner.’ [4]

He then came to ‘cheapness or plenty, or, which is the same thing, the most proper way of securing wealth and abundance’. [I-xxi] He began this part of the subject by considering the ‘natural wants of mankind which are to be supplied,’ [1] a subject which has since acquired the title of ‘consumption’ in economic treatises. Then he showed that opulence arises from division of labour, and why this is so, or how the division of labour ‘occasions a multiplication of the product,’ [2] and why it must be proportioned to the extent of commerce. ‘Thus,’ he said, ‘the division of labour is the great cause of the increase of public opulence, which is always proportioned to the industry of the people, and not to the quantity of gold and silver as is foolishly imagined’. ‘Having thus shown what gives occasion to public opulence,’ he said he would go on to consider:—

‘First, what circumstances regulate the price of commodities:

‘Secondly, money in two different views, first as the measure of value and then as the instrument of commerce:

‘Thirdly, the history of commerce, in which shall be taken notice of the causes of the slow progress of opulence, both in ancient and modern times, which causes shall be shown either to affect agriculture or arts and manufactures:

‘Lastly, the effects of a commercial spirit, on the government, temper, and manners of a people, whether good or bad, and the proper remedies.’ [3]

Under the first of these heads he treated of natural and market price and of differences of wages, and showed ‘that whatever police tends to raise the market price above the natural, tends to diminish public opulence’. [4] Among such pernicious regulations he enumerated taxes upon necessaries, monopolies, and exclusive privileges of corporations. Regulations which bring market price below natural price he regarded as equally pernicious, and therefore he condemned the corn bounty, which attracted into agriculture stock which would have been better employed in some other trade. ‘It is by far the best police to leave things to their natural course.’ [5]

Under the second head he explained the reasons for the use of money as a common standard and its consequential use as the instrument of commerce. He showed why gold and silver were commonly chosen and why coinage was introduced, and proceeded [I-xxii] to explain the evils of tampering with the currency, and the difficulty of keeping gold and silver money in circulation at the same time. Money being a dead stock, banks and paper credit, which enable money to be dispensed with and sent abroad, are beneficial. The money sent abroad will ‘bring home materials for food, clothes, and lodging,’ and, ‘whatever commodities are imported, just so much is added to the opulence of the country’. [1] It is ‘a bad police to restrain’ banks. [2] Mun, ‘a London merchant,’ affirmed ‘that as England is drained of its money it must go to ruin’. [3] ‘Mr. Gee, likewise a merchant,’ endeavoured to ‘show that England would soon be ruined by trade with foreign countries,’ and that ‘in almost all our commercial dealings with other nations we are losers’. [4] Mr. Hume had shown the absurdity of these and other such doctrines, though even he had not kept quite clear of ‘the notion that public opulence consists in money’. [5] Money is not consumable, and ‘the consumptibility, if we may use the word, of goods, is the great cause of human industry’. [6]

The absurd opinion that riches consist in money had given rise to ‘many prejudicial errors in practice,’ [7] such as the prohibition of the exportation of coin and attempts to secure a favourable balance of trade. There will always be plenty of money if things are left to their free course, and no prohibition of exportation will be effectual. The desire to secure a favourable balance of trade has led to ‘most pernicious regulations,’ [8] such as the restrictions on trade with France.

‘The absurdity of these regulations will appear on the least reflection. All commerce that is carried on betwixt any two countries must necessarily be advantageous to both. The very intention of commerce is to exchange your own commodities for others which you think will be more convenient for you. When two men trade between themselves it is undoubtedly for the advantage of both. . . . The case is exactly the same betwixt any two nations. The goods which the English merchants want to import from France are certainly more valuable to them than what they give for them.’ [9]

These jealousies and prohibitions were most hurtful to the richest nations, and it would benefit France and England especially, if ‘all [I-xxiii] national prejudices were rooted out and a free and uninterrupted commerce established’. [1] No nation was ever ruined by this balance of trade. All political writers since the time of Charles II. had been prophesying ‘that in a few years we would be reduced to an absolute state of poverty,’ but ‘we find ourselves far richer than before’. [2]

The erroneous notion that national opulence consists in money had also given rise to the absurd opinion that ‘no home consumption can hurt the opulence of a country’. [3]

It was this notion too that led to Law’s Mississippi scheme, compared to which our own South Sea scheme was a trifle. [4]

Interest does not depend on the value of money, but on the quantity of stock. Exchange is a method of dispensing with the transmission of money. [5]

Under the third heading, the history of commerce, or the causes of the slow progress of opulence, Adam Smith dealt with ‘first, natural impediments, and secondly, the oppression of civil government’. [6] He is not recorded to have mentioned any natural impediments except the absence of division of labour in rude and barbarous times owing to the want of stock. [7] But on the oppression of civil government he had much to say. At first governments were so feeble that they could not offer their subjects that security without which no man has any motive to be industrious. Afterwards, when governments became powerful enough to give internal security, they fought among themselves, and their subjects were harried by foreign enemies. Agriculture was hindered by great tracts of land being thrown into the hands of single persons. This led at first to cultivation by slaves, who had no motive to industry; then came tenants by steelbow (metayers) who had no sufficient inducement to improve the land; finally the present method of cultivation by tenants was introduced, but these for a long time were insecure in their holdings, and had to pay rent in kind, which made them liable to be severely affected by bad seasons. Feudal subsidies discouraged industry, the law of primogeniture, entails, and the expense of transferring land prevented the large estates from being divided. The restrictions [I-xxiv] on the export of corn helped to stop the progress of agriculture. Progress in arts and commerce was also hindered by slavery, as well as by the ancient contempt for industry and commerce, by the want of enforcement of contracts, by the various difficulties and dangers of transport, by the establishment of fairs, markets and staple towns, by duties on imports and exports, and by monopolies, corporation privileges, the statute of apprenticeship and bounties. [1]

Under the fourth and last head, the influence of commerce on the manners of a people, Smith pronounced that ‘whenever commerce is introduced into any country probity and punctuality always accompany it’. [2] The trader deals so often that he finds honesty is the best policy. ‘Politicians are not the most remarkable men in the world for probity and punctuality. Ambassadors from different nations are still less so,’ [3] the reason being that nations treat with one another much more seldom than merchants.

But certain inconveniences arise from a commercial spirit. Men’s views are confined, and ‘when a person’s whole attention is bestowed on the seventeenth part of a pin or the eightieth part of a button,’ [4] he becomes stupid. Education is neglected. In Scotland the meanest porter can read and write, but at Birmingham boys of six or seven can earn threepence or sixpence a day, so that their parents set them to work early and their education is neglected. To be able merely to read is good as it ‘gives people the benefit of religion, which is a great advantage, not only considered in a pious sense, but as it affords them subject for thought and speculation.’ [5] There is too ‘another great loss which attends the putting boys too soon to work’. The boys throw off parental authority, and betake themselves to drunkenness and riot. The workmen in the commercial parts of England are consequently in a ‘despicable condition; their work through half the week is sufficient to maintain them, and through want of education they have no amusement for the other but riot and debauchery. So it may very justly be said that the people who clothe the whole world are in rags themselves.’ [6]

[I-xxv]

Further, commerce sinks courage and extinguishes martial spirit; the defence of the country is handed over to a special class, and the bulk of the people grow effeminate and dastardly, as was shown by the fact that in 1745 ‘four or five thousand naked unarmed Highlanders would have overturned the government of Great Britain with little difficulty if they had not been opposed by a standing army’. [1]

‘To remedy’ these evils introduced by commerce ‘would be an object worthy of serious attention.’

Revenue, at any rate in the year when the notes of his lectures were made, was treated by Adam Smith before the last head of police just discussed, ostensibly on the ground that it was in reality one of the causes of the slow progress of opulence. [2]

Originally, he taught, no revenue was necessary; the magistrate was satisfied with the eminence of his station and any presents he might receive. The receipt of presents soon led to corruption. At first too soldiers were unpaid, but this did not last. The earliest method adopted for supplying revenue was assignment of lands to the support of government. To maintain the British government would require at least a fourth of the whole of the land of the country. ‘After government becomes expensive, it is the worst possible method to support it by a land rent.’ [3] Civilisation and expensive government go together.

Taxes may be divided into taxes upon possessions and taxes upon commodities. It is easy to tax land, but difficult to tax stock or money; the land tax is very cheaply collected and does not raise the price of commodities and thus restrict the number of persons who have stock sufficient to carry on trade in them. It is hard on the landlords to have to pay both land tax and taxes on consumption, which fact ‘perhaps occasions the continuance of what is called the Tory interest’. [4]

Taxes on consumptions are best levied by way of excise. They have the advantage of ‘being paid imperceptibly,’ [5] since ‘when we buy a pound of tea we do not reflect that the most part of the price is a duty paid to the government, and therefore pay it contentedly, [I-xxvi] as though it were only the natural price of the commodity’. [1] Such taxes too are less likely to ruin people than a land tax, as they can always reduce their expenditure on dutiable articles.

A fixed land tax like the English is better than one which varies with the rent like the French, and ‘the English are the best financiers in Europe, and their taxes are levied with more propriety than those of any other country whatever’. [2] Taxes on importation are hurtful because they divert industry into an unnatural channel, but taxes on exportation are worse. The common belief that wealth consists in money has not been so hurtful as might have been expected in regard to taxes on imports, since it has accidentally led to the encouragement of the import of raw material and discouragement of the import of manufactured articles. [3]

From treating of revenue Adam Smith was very naturally led on to deal with national debts, and this led him into a discussion of the causes of the rise and fall of stocks and the practice of stockjobbing. [4]

Under Arms he taught that at first the whole people goes out to war: then only the upper classes go and the meanest stay to cultivate the ground. But afterwards the introduction of arts and manufactures makes it inconvenient for the rich to leave their business, and the defence of the state falls to the meanest. ‘This is our present condition in Great Britain.’ [5] Discipline now becomes necessary and standing armies are introduced. The best sort of army is ‘a militia commanded by landed gentlemen in possession of the public offices of the nation,’ [6] which ‘can never have any prospect of sacrificing the liberties of the country’. This is the case in Sweden.

Now let us compare with this the drift of the Wealth of Nations, not as it is described in the ‘Introduction and Plan,’ but as we find it in the body of the work itself.

Book I. begins by showing that the greatest improvement in the productive powers of industry is due to division of labour. From division of labour it proceeds to money, because money is necessary [I-xxvii] in order to facilitate division of labour, which depends upon exchange. This naturally leads to a discussion of the terms on which exchanges are effected, or value and price. Consideration of price reveals the fact that it is divided between wages, profit and rent, and is therefore dependent on the rates of wages, profit and rent, so that it is necessary to discuss in four chapters variations in these rates.

Book II. treats first of the nature and divisions of stock, secondly of a particularly important portion of it, namely money, and the means by which that part may be economised by the operations of banking, and thirdly the accumulation of capital, which is connected with the employment of productive labour. Fourthly it considers the rise and fall of the rate of interest, and fifthly and lastly the comparative advantage of different methods of employing capital.

Book III. shows that the natural progress of opulence is to direct capital, first to agriculture, then to manufactures, and lastly to foreign commerce, but that this order has been inverted by the policy of modern European states.

Book IV. deals with two different systems of political economy: (1) the system of commerce, and (2) the system of agriculture, but the space given to the former, even in the first edition, is eight times as great as that given to the latter. The first chapter shows the absurdity of the principle of the commercial or mercantile system, that wealth is dependent on the balance of trade; the next five discuss in detail and show the futility of the various mean and malignant expedients by which the mercantilists endeavoured to secure their absurd object, namely, general protectionist duties, prohibitions and heavy duties directed against the importation of goods from particular countries with which the balance is supposed to be disadvantageous, drawbacks, bounties, and treaties of commerce. The seventh chapter, which is a long one, deals with colonies. According to the forecast at the end of chapter i. this subject comes here because colonies were established in order to encourage exportation by means of peculiar privileges and monopolies. But in the chapter itself there is no sign of this. The history and progress of colonies is discussed for its own sake, [I-xxviii] and it is not alleged that important colonies have been founded with the object suggested in chapter i.

In the last chapter of the Book, the physiocratic system is described, and judgement is pronounced against it as well as the commercial system. The proper system is that of natural liberty, which discharges the sovereign from ‘the duty of superintending the industry of private people and of directing it towards the employments most suitable to the interest of the society’.

Book V. deals with the expenses of the sovereign in performing the duties left to him, the revenues necessary to meet those expenses and the results of expenses exceeding revenue. The discussion of expenses of defence includes discussion of different kinds of military organisation, courts of law, means of maintaining public works, education, and ecclesiastical establishments.

Putting these two sketches together we can easily see how closely related the book is to the lectures.

The title ‘Police’ being dropped as not sufficiently indicating the subject, there is no necessity for the mention of cleanliness, and the remarks on security are removed to the chapter on the accumulation of capital. The two sections on the natural wants of mankind are omitted, [1] illustrating once more the difficulty which economists have generally felt about consumption. The next four sections, on division of labour, develop into the first three chapters of Book I. of the Wealth of Nations. At this point in the lectures there is an abrupt transition to prices, followed by money, the history of commerce and the effects of a commercial spirit, but in the Wealth of Nations this is avoided by taking money next, as the machinery by the aid of which labour is divided, and then proceeding by a very natural transition to prices. In the lectures the discussion of money led to a consideration of the notion that wealth consisted in money and of all the pernicious consequences of that delusion in restricting banking and foreign trade. This was evidently overloading the theory of money, and consequently banking is postponed to the Book about capital, on the ground that it dispenses with money, which is a dead stock, and thus economises capital, while the commercial policy is relegated [I-xxix] by itself to Book IV. In the lectures, again, wages are only dealt with slightly under prices, and profits and rent not at all; in the Wealth of Nations wages, profits and rent are dealt with at length as component parts of price, and the whole produce of the country is said to be distributed into them as three shares.

The next part of the lectures, that dealing with the causes of the slow progress of opulence, forms the foundation for Book III. of the Wealth of Nations. The influence of commerce on manners disappears as an independent heading, but most of the matter dealt with under it is utilised in the discussions of education and military organisation.

Besides consumption, two other subjects, stock-jobbing and the Mississippi scheme, which are treated at some length in the lectures, are altogether omitted in the Wealth of Nations. The description of stock-jobbing was probably left out because better suited to the youthful hearers of the lectures than to the maturer readers of the book. The Mississippi scheme was omitted, Smith himself says, because it had been adequately discussed by Du Verney.

Here and there discrepancies may be found between the opinions expressed in the lectures and those expressed in the book. The reasonable and straightforward view of the effects of the corn bounty is replaced by a more recondite though less satisfactory doctrine. The remark as to the inconvenience of regulations on foreign commerce having been alleviated by the fact that they encourage trade with countries from which imported raw materials came and discourage it with those from which manufactured goods came [1] does not reappear in the book. The passage in the Lectures is probably much condensed, and perhaps misrepresents what Adam Smith said. If it does not, it shows him to have been not entirely free from protectionist fallacies at the time the lectures were delivered. [2]

There are some very obvious additions, the most prominent being the account of the French physiocratic or agricultural system which occupies the last chapter of Book IV. The article on the relations of church and state (Bk. V., ch. i., pt. iii., art. 3) also appears to be a clear addition, at any rate in so far as the lectures on police [I-xxx] and revenue are concerned, but, as we shall see presently, tradition seems to say that Smith did deal with ecclesiastical establishments in this department of his lectures on jurisprudence, so that possibly the lecture notes are deficient at this particular point, or the subject was omitted for the particular year in which the notes were taken. Then there is the long chapter on colonies. The fact of colonies having attracted Adam Smith’s attention during the interval between the lectures and the publication of his book is not very surprising when we remember that the interval coincided almost exactly with the period from the beginning of the attempt to tax the colonies to the Declaration of Independence.

But these additions are of small importance compared with the introduction of the theory of stock or capital and unproductive labour in Book II., the slipping of a theory of distribution into the theory of prices towards the end of Book I., chapter vi., and the emphasising of the conception of annual produce. These changes do not make so much real difference to Smith’s own work as might be supposed; the theory of distribution, though it appears in the title of Book I., is no essential part of the work and could easily be excised by deleting a few paragraphs in Book I., chapter vi., and a few lines elsewhere; if Book II. were altogether omitted the other Books could stand perfectly well by themselves. But to subsequent economics they were of fundamental importance. They settled the form of economic treatises for a century at least.

They were of course due to the acquaintance with the French Économistes which Adam Smith made during his visit to France with the Duke of Buccleugh in 1764-6. It has been said that he might have been acquainted with many works of this school before the notes of his lectures were taken, and so he might. But the notes of his lectures are good evidence to show that as a matter of fact he was not, or at any rate that he had not assimilated their main economic theories. When we find that there is no trace of these theories in the Lectures and a great deal in the Wealth of Nations, and that in the meantime Adam Smith had been to France and mixed with all the prominent members of the ‘sect,’ including their master, Quesnay, it is difficult to understand why we should be asked, without any evidence, to refrain from believing that he [I-xxxi] came under physiocratic influence after and not before or during his Glasgow period.

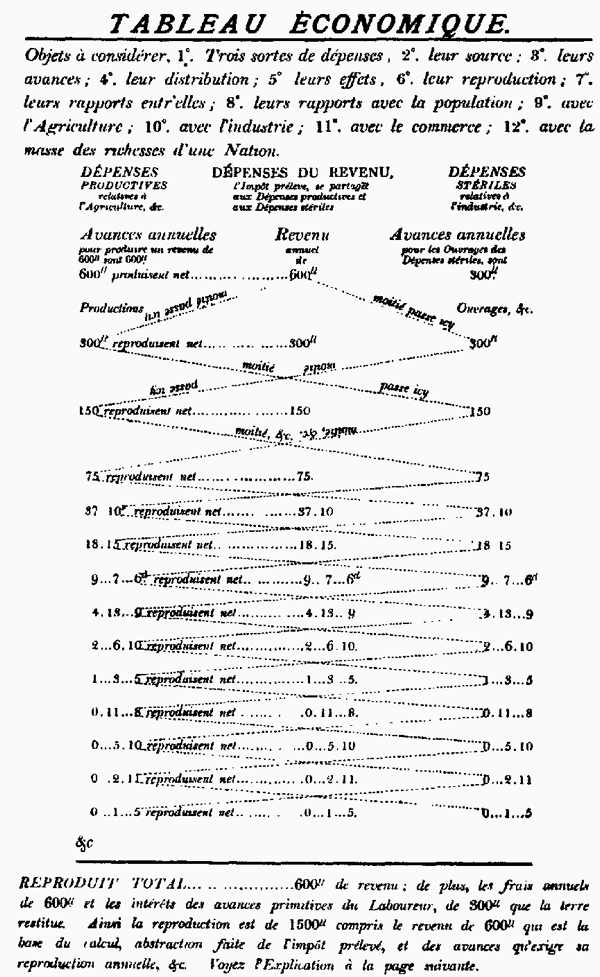

The confession of faith of the Économistes is embodied in Quesnay’s Tableau Économique, which one of them described as worthy of being ranked, along with writing and money, as one of the three greatest inventions of the human race. [1] It is reprinted on the next page from the facsimile of the edition of 1759, published by the British Economic Association (now the Royal Economic Society) in 1894.

Those who are curious as to the exact meaning of the zigzag lines may study Quesnay’s Explication, which the British Economic Association published along with the table in 1894. For our present purposes it is sufficient to see (1) that it involves a conception of the whole annual produce or reproduction of a country; (2) that it teaches that some labour is unproductive, that to maintain the annual produce certain ‘ avances ’ are necessary, and that this annual produce is ‘distributed’. Adam Smith, as his chapter on agricultural systems shows, did not appreciate the minutiæ of the table very highly, but he certainly took these main ideas and adapted them as well as he could to his Glasgow theories. With those theories the conception of an annual produce was in no way inconsistent, and he had no difficulty in adopting annual produce as the wealth of a nation, though he very often forgetfully falls back into older ways of speaking. As to unproductive labour, he was not prepared to condemn the whole of Glasgow industry as sterile, but was ready to place the mediæval retainer and even the modern menial servant in the unproductive class. He would even go a little farther and put along with them all whose labour did not produce particular vendible objects, or who were not employed for the money-gain of their employers. Becoming somewhat confused among these distinctions and the physiocratic doctrine of ‘ avances, ’ he imagined a close connexion between the employment of productive labour and the accumulation and employment of capital. Hence with the aid of the common observation that where a capitalist appears, labourers soon spring up, he arrived at the view that the amount of capital in a country determines [I-xxxii] the number of ‘useful and productive’ labourers. Finally he slipped into his theory of prices and their component parts the suggestion that as the price of any one commodity is divided between wages, profits and rent, so the whole produce is divided between labourers, capitalists, and landlords.

[I-xxxiii]

These ideas about capital and unproductive labour are certainly of great importance in the history of economic theory, but they were fundamentally unsound, and were never so universally accepted as is commonly supposed. The conception of the wealth of nations as an annual produce, annually distributed, however, has been of immense value. Like other conceptions of the kind it was certain to come. It might have been evolved direct from Davenant or Petty nearly a century before. We need not suppose that some one else would not soon have given it its place in English economics if Adam Smith had not done so, but that need not deter us from recording the fact that it was he who introduced it, and that he introduced it in consequence of his association with the Économistes.

If we attempt to carry the history of the origin of the Wealth of Nations farther back than the date of the lecture notes in 1763 or thereabouts, we can still find a small amount of authentic information. We know that Smith must have been using practically the same divisions in his lectures in 1759, since he promises in the last paragraph of the Moral Sentiments published in that year, ‘another discourse’ in which he would ‘endeavour to give an account of the general principles of law and government, and of the different revolutions they have undergone in the different ages and periods of society, not only in what concerns justice, but in what concerns police, revenue and arms, and whatever else is the object of law.’ It seems probable, however, that the economic portion of the lectures was not always headed ‘police, revenue, and arms,’ since Millar, who attended the lectures when they were first delivered in 1751-2, says:—

‘In the last part of his lectures he examined those political regulations which are founded not upon the principle of justice, but that of expediency, and which are calculated to increase the riches, the power and the prosperity of a state. Under this view, he considered the political institutions relating to commerce, to finances, to ecclesiastical and military establishments. What [I-xxxiv] he delivered on these subjects contained the substance of the work he afterwards published under the title of “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations”.’ [1]

Of course this is not necessarily inconsistent with the economic lectures having been denominated police, revenue, and arms, even at that early date, but the italicising of ‘justice’ and ‘expediency,’ if due to Millar, rather suggests the contrary, and there is no denying that the arrangement of ‘cheapness or plenty’ under ‘police’ may very well have been an afterthought fallen upon to justify the introduction of a mass of economic material into lectures on Jurisprudence. As to the reason why that introduction took place the circumstances of Smith’s first active session at Glasgow suggest another motive besides his love for the subject, which, we may notice, did not prevent him from publishing his views on Ethics first.

His first appointment at Glasgow, it must be remembered, was to the Professorship of Logic in January, 1751, but his engagements at Edinburgh prevented his performing the duties that session. Before the beginning of next session he was asked to act as deputy for Craigie, the Professor of Moral Philosophy, who was going away for the benefit of his health. He consented, and consequently in the session of 1751-2 he had to begin the work of two professorships, as to one of which he had very little previous warning. [2] Every teacher in such a position would do his best to utilise any suitable material which he happened to have by him, and most men would even stretch a point to utilise even what was not perfectly suitable.

Now we know that Adam Smith possessed in manuscript in the hand of a clerk employed by him certain lectures which he read at Edinburgh in the winter of 1750-1, and we know that in these lectures he preached the doctrine of the beneficial effects of freedom, and, according to Dugald Stewart, ‘many of the most important opinions in the Wealth of Nations ’. There existed when Stewart wrote, ‘a short manuscript drawn up by Mr. Smith in the year [I-xxxv] 1755 and presented by him to a society of which he was then a member’. Stewart says of this paper:—

‘Many of the most important opinions in The Wealth of Nations are there detailed; but I shall quote only the following sentences: “Man is generally considered by statesmen and projectors as the materials of a sort of political mechanics. Projectors disturb nature in the course of her operations in human affairs; and it requires no more than to let her alone, and give her fair play in the pursuit of her ends that she may establish her own designs.” And in another passage: “Little else is requisite to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice; all the rest being brought about by the natural course of things. All governments which thwart this natural course, which force things into another channel or which endeavour to arrest the progress of society at a particular point, are unnatural, and to support themselves are obliged to be oppressive and tyrannical.—A great part of the opinions,” he observes, “enumerated in this paper is treated of at length in some lectures which I have still by me, and which were written in the hand of a clerk who left my service six years ago. They have all of them been the constant subjects of my lectures since I first taught Mr. Craigie’s class, the first winter I spent in Glasgow, down to this day, without any considerable variation. They had all of them been the subjects of lectures which I read at Edinburgh the winter before I left it, and I can adduce innumerable witnesses both from that place and from this, who will ascertain them sufficiently to be mine.” ’ [1]

It seems then that, when confronted with the two professorial chairs in 1751, Smith had by him some lectures on progress, very likely explaining ‘the slow progress of opulence,’ and that, as anyone in such circumstances would have liked to do, he put them into his moral philosophy course.

As it happened, there was no difficulty in doing this. It seems nearly certain that Craigie himself suggested that it should be done. The request that Smith would take Craigie’s work came through Cullen, and in answering Cullen’s letter, which has not been preserved, Smith says, ‘You mention natural jurisprudence and politics as the parts of his lectures which it would be most agreeable for me to teach. I shall very willingly undertake both.’ [2] Craigie doubtless knew what Smith had been lecturing upon in Edinburgh in the previous winter and called it ‘politics’.

Moreover the traditions of the Chair of Moral Philosophy, as [I-xxxvi] known to Adam Smith, required a certain amount of economics. A dozen years earlier he had himself been a student when Francis Hutcheson was professor. So far as we can judge from Hutcheson’s System of Moral Philosophy, which, as Dr. W. R. Scott has shown, [1] was already in existence when Smith was a student, though not published till 1755, Hutcheson lectured first on Ethics, next upon what might very well be called Natural Jurisprudence, and thirdly upon Civil Polity. Through the two latter parts a considerable quantity of economic doctrine is scattered.

In considering ‘The Necessity of a Social Life,’ Hutcheson points out that a man in solitude, however strong and instructed in the arts, ‘could scarce procure to himself the bare necessaries of life even in the best soils or climates’.

‘Nay ’tis well known that the produce of the labours of any given number, twenty for instance, in providing the necessaries or conveniences of life, shall be much greater by assigning to one a certain sort of work of one kind in which he will soon acquire skill and dexterity, and to another assigning work of a different kind, than if each one of the twenty were obliged to employ himself by turns in all the different sorts of labour requisite for his subsistence without sufficient dexterity in any. In the former method each procures a great quantity of goods of one kind, and can exchange a part of it for such goods obtained by the labours of others as he shall stand in need of. One grows expert in tillage, another in pasture and breeding cattle, a third in masonry, a fourth in the chase, a fifth in iron-works, a sixth in the arts of the loom, and so on throughout the rest. Thus all are supplied by means of barter with the works of complete artists. In the other method scarce any one could be dexterous and skilful in any one sort of labour.

‘Again, some works of the highest use to multitudes can be effectually executed by the joint labours of many, which the separate labours of the same number could never have executed. The joint force of many can repel dangers arising from savage beasts or bands of robbers which might have been fatal to many individuals were they separately to encounter them. The joint labours of twenty men will cultivate forests or drain marshes, for farms to each one, and provide houses for habitation and inclosures for their flocks, much sooner than the separate labours of the same number. By concert and alternate relief they can keep a perpetual watch, which without concert they could not accomplish.’ [2]

[I-xxxvii]

In explaining the ‘Foundation of Property’ Hutcheson says that when population was scanty, the country fertile and the climate mild, there was not much need for developing the rules of property, but as things are, ‘universal industry is plainly necessary for the support of mankind’ and men must be excited to labour by self-interest and family affection. If the fruits of men’s labours are not secured to them, ‘one has no other motive to labour than the general affection to his kind, which is commonly much weaker than the narrower affections to our friends and relations, not to mention the opposition which in this case would be given by most of the selfish ones’. Willing industry could not be secured in a communistic society. [1]

The largest continuous block of economic doctrine in the System of Moral Philosophy is to be found in the chapter on ‘The Values of Goods in Commerce and the Nature of Coin’ which occurs in the middle of the discussion of contracts. In this chapter it is pointed out that it is necessary for commerce that goods should be valued. The values of goods depend on the demand for them and the difficulty of acquiring them. Values must be measured by some common standard, and this standard must be something generally desired, so that men may be generally willing to take it in exchange. To secure this it should be something portable, divisible without loss, and durable. Gold and silver best fulfil these requirements. At first they were used by quantity or weight, without coinage, but eventually the state vouched for quantity and quality by its stamp. The stamp being ‘easy workmanship’ adds no considerable value. ‘Coin is ever valued as a commodity in commerce as well as other goods; and that in proportion to the rarity of the metal, for the demand is universal.’ The only way to raise its value artificially would be by restricting the produce of the mines.

‘We say indeed commonly, that the rates of labour and goods have risen since these metals grew plenty; and that the rates of labour and goods were low when the metals were scarce; conceiving the value of the metals as invariable, because the legal names of the pieces, the pounds, shillings or pence, continue to them always the same till a law alters them. But a day’s digging or ploughing was as uneasy to a man a thousand years ago as it is now, though he could not then get so much silver for it: and a barrel of wheat, or beef, [I-xxxviii] was then of the same use to support the human body, as it is now when it is exchanged for four times as much silver. Properly, the value of labour, grain, and cattle are always pretty much the same, as they afford the same uses in life, where no new inventions of tillage or pasturage cause a greater quantity in proportion to the demand.’ [1]

Lowering and raising the coins are unjust and pernicious operations. Copious mines abate the value of the precious metals.

‘The standard itself is varying insensibly; and therefore if we would settle fixed salaries which in all events would answer the same purposes of life, or support those entituled to them in the same condition with respect to others, they should neither be fixed in the legal names of coin, nor in a certain number of ounces of gold and silver. A decree of state may change the legal names; and the value of the ounces may alter by the increase or decrease of the quantities of these metals. Nor should such salaries be fixed in any quantities of more ingenious manufactures, for nice contrivances to facilitate labour may lower the value of such goods. The most invariable salary would be so many days labour of men, or a fixed quantity of goods produced by the plain inartificial labours, such goods as answer the ordinary purposes of life. Quantities of grain come nearest to such a standard.’ [2]

Prices of goods depend upon the expenses, the interest of money employed, and the ‘labours too, the care, attention, accounts and correspondence about them’. Sometimes we must ‘take in also the condition of the person so employed,’ since ‘the expense of his station of life must be defrayed by the price of such labours; and they deserve compensation as much as any other. This additional price of their labours is the just foundation of the ordinary profit of merchants.’

In the next chapter, on ‘The Principal Contracts in a Social Life,’ we find the rent or hire of unfruitful goods, such as houses, justified on the ground that the proprietor might have employed his money or labour on goods naturally fruitful.

‘If in any way of trade men can make far greater gains by help of a large stock of money than they could have made without it, ’tis but just that he who supplies them with the money, the necessary means of this gain, should have for the use of it some share of the profit, equal at least to the profit he could have made by purchasing things naturally fruitful or yielding a rent. This shows the just foundation of interest upon money lent, though it be not naturally fruitful. Houses yield no fruits or increase, nor will some arable grounds yield any without great labour. Labour employed in managing [I-xxxix] money in trade or manufactures will make it as fruitful as anything. Were interest prohibited, none would lend except in charity; and many industrious hands who are not objects of charity would be excluded from large gains in a way very advantageous to the public.’ [1]

Reasonable interest varies with the state of trade and the quantity of coin. In a newly settled country great profits are made by small sums, and land is worth fewer years’ purchase, so that a higher interest is reasonable. Laws in settling interest must follow ‘these natural causes,’ otherwise they will be evaded. [2]

In the chapter ‘Of the Nature of Civil Laws and their Execution,’ we find that after piety the virtues most necessary to a state are sobriety, industry, justice and fortitude.

‘Industry is the natural mine of wealth, the fund of all stores for exportation by the surplus of which beyond the value of what a nation imports, it must increase in wealth and power. Diligent agriculture must furnish the necessaries of life and the materials for all manufactures; and all mechanic arts should be encouraged to prepare them for use and exportation. Goods prepared for export should generally be free from all burdens and taxes, and so should the goods be which are necessarily consumed by the artificers, as much as possible; that no other country be able to undersell like goods at a foreign market. Where one country alone has certain materials, they may safely impose duties upon them when exported; but such moderate ones as shall not prevent the consumption of them abroad.

‘If people have not acquired an habit of industry, the cheapness of all the necessaries of life rather encourages sloth. The best remedy is to raise the demand for all necessaries; not merely by premiums upon exporting them, which is often useful too; but by increasing the number of people who consume them; and when they are dear, more labour and application will be requisite in all trades and arts to procure them. Industrious foreigners should therefore be invited to us, and all men of industry should live with us unmolested and easy. Encouragement should be given to marriage and to those who rear a numerous offspring to industry. The unmarried should pay higher taxes as they are not at the charge of rearing new subjects to the state. Any foolish notions of meanness in mechanic arts, as if they were unworthy of men of better families, should be borne down, and men of better condition as to birth or fortune engaged to be concerned in such occupations. Sloth should be punished by temporary servitude at least. Foreign materials should be imported and even premiums given, when necessary, that all our own hands may be employed; and that, by exporting them again manufactured, we may obtain from abroad the price of our labours. Foreign manufactures and products ready for consumption should be made dear to the consumer by high duties, [I-xl] if we cannot altogether prohibit the consumption; that they may never be used by the lower and more numerous orders of the people whose consumption would be far greater than those of the few who are wealthy. Navigation, or the carriage of goods foreign or domestic, should be encouraged, as a gainful branch of business surpassing often all the profit made by the merchant. This too is a nursery of fit hands for defence at sea.

‘ ’Tis vain to allege that luxury and intemperance are necessary to the wealth of a state as they encourage all labour and manufactures by making a great consumption. It is plain there is no necessary vice in the consuming of the finest products or the wearing of the dearest manufactures by persons whose fortunes can allow it consistently with the duties of life. And what if men grew generally more frugal and abstemious in such things? more of these finer goods could be sent abroad; or if they could not, industry and wealth might be equally promoted by the greater consumption of goods less chargeable: as he who saves by abating of his own expensive splendour could by generous offices to his friends, and by some wise methods of charity to the poor, enable others to live so much better and make greater consumption than was made formerly by the luxury of one. . . . Unless therefore a nation can be found where all men are already provided with all the necessaries and conveniencies of life abundantly, men may, without any luxury, make the very greatest consumption by plentiful provision for their children, by generosity and liberality to kinsmen and indigent men of worth, and by compassion to the distresses of the poor.’ [1]

Under ‘Military skill and fortitude’ Hutcheson discusses what Adam Smith afterwards placed under ‘Arms,’ and decides in favour of a trained militia. [2]

In the same chapter he has a section with the marginal title ‘what taxes or tributes most eligible,’ which contains a repudiation of the policy of taxation for revenue only:—

‘As to taxes for defraying the public expenses, these are most convenient which are laid on matters of luxury and splendour rather than the necessaries of life; on foreign products and manufactures rather than domestic; and such as can be easily raised without many expensive offices for collecting them. But above all, a just proportion to the wealth of people should be observed in whatever is raised from them, otherways than by duties upon foreign products and manufactures, for such duties are often necessary to encourage industry at home, though there were no public expenses.’ [3]

This proportionment of taxation to wealth he thinks cannot be attained except by means of periodical estimation of the wealth of families, since land taxes unduly oppress landlords in debt and let [I-xli] moneyed men go free, while duties and excises are paid by the consumer, so that ‘hospitable generous men or such as have numerous families supported genteelly bear the chief burden here, and the solitary sordid miser bears little or no share of it’. [1]

It is quite clear from all this that Smith was largely influenced by the traditions of his chair in selecting his economic subjects. Dr. Scott draws attention to the curious fact that the very order in which the subjects happen to occur in Hutcheson’s System is almost identical with the order in which the same subjects occur in Smith’s Lectures. [2] We are strongly tempted to surmise that when Smith had hurriedly to prepare his lectures for Craigie’s class, he looked through his notes of his old master’s lectures (as hundreds of men in his position have done before and after him) and grouped the economic subjects together as an introduction and sequel to the lectures which he had brought with him from Edinburgh. Hutcheson was an inspiring teacher. His colleague, Leechman, says:—

‘As he had occasion every year in the course of his lectures to explain the origin of government and compare the different forms of it, he took peculiar care, while on that subject, to inculcate the importance of civil and religious liberty to the happiness of mankind: as a warm love of liberty and manly zeal for promoting it were ruling principles in his own breast, he always insisted upon it at great length and with the greatest strength of argument and earnestness of persuasion: and he had such success on this important point, that few, if any, of his pupils, whatever contrary prejudices they might bring along with them, ever left him without favourable notions of that side of the question which he espoused and defended’. [3]

Half a century later Adam Smith spoke of the Glasgow Chair of Moral Philosophy as an ‘office to which the abilities and virtues of the never-to-be-forgotten Dr. Hutcheson had given a superior degree of illustration’. [4]