JOHN WADE,

Appendix to the Black Book: An Exposition of the Principles and Practices of the Reform Ministry and Parliament ... (1835)

|

[Created: 7 May, 2023]

[Updated: June 28, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, Appendix to the Black Book: An Exposition of the Principles and Practices of the Reform Ministry and Parliament: the Church and the Dissenters; Catastrophe of The House of Lords; and Prospects of Tory Misrule ... (London: Effingham Wilson, 1835).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1835_Wade_BlackBookAppendix/Wade_BlackBook1835-Appendix-ebook.html

John Wade, Appendix to the Black Book: An Exposition of the Principles and Practices of the Reform Ministry and Parliament: the Church and the Dissenters; Catastrophe of The House of Lords; and Prospects of Tory Misrule: With Tables of Ecclesiastical and Election Statistics, and Corrections of Former Editions of The Black Book. By the Original Editor. Sixth Edition, with The ‘Crisis’ and a Characteristic List of the Anti-Reform Government. (London: Published By Effingham Wilson, Royal Exchange. MDCCCXXXV (1835)).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

[xi]

CONTENTS.

- The ‘Crisis’ page iii

- Advertisement to the First Edition p. vii

- CHAPTER I. General Principles and Practices of the Reform Ministry p. 2

- CHAPTER II. The Plough and the Loom; or, the relative importance of Agricultural and Commercial Industry p. 13

- CHAPTER III. The Church and the Dissenters:

- 1. Utility of an Established Church p. 24

- 2. Measures for the Relief of Dissenters p. 27

- 3. Tenure of Church Property p. 31

- CHAPTER IV. Working of the Excise Laws p. 34

- CHAPTER V. Poor Laws’ Amendment Act p. 38

- Lord Brougham’s Speech on the Poor Laws p. 46

- CHAPTER VI. Catastrophe of the House of Lords p. 49

- CHAPTER VII. Character and Composition of the First Reform Parliament p. 56

- CHAPTER VIII. Dissolution and Character of the Reform Ministry p. 63

- CHAPTER IX. The Duke of Wellington and the Tories p. 72 [xii]

- I. Report of the Commissioners of Ecclesiastical Revenue p. 76

- II. Remarks on the Ecclesiastical Report p. 78

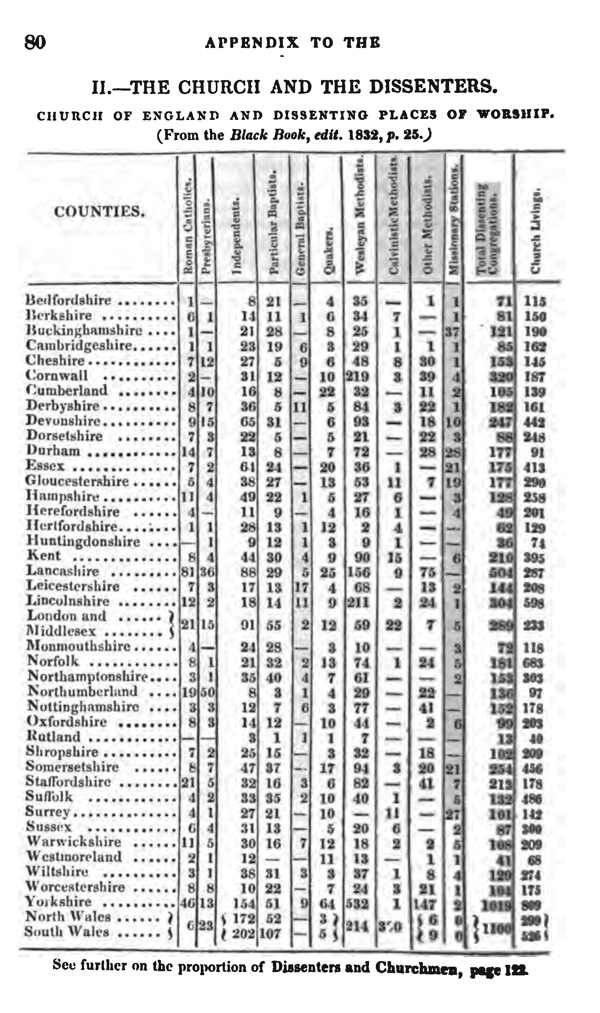

- III. Table of the Number of Church of England and Dissenting Places of Worship in the several Counties of England and in Wales p. 80

- IV. Public Offices—Commissions of Inquiry—Income of Public Charities—Grants of Ireland p. 81

- V. Representation of England and Wales at the last General Election p. 82

- VII. Lists of Majorities and Minorities during the last Two Sessions p. 94

- 1. Division on the Ballot p. 94

- 2. Naval and Military Sinecures p. 97

- 3. Bishops in the East Indies p. 98

- 4. West India Question p. 99

- 5. Chandos’ Motion on Agriculture p. 100

- 6. Session 1834.—Hume’s Motion on the Corn-Laws p. 100

- 7. Harvey’s Motion on the Pension-List p. 104

- 8. Repeal of the Septennial Act p. 107

- 9. Dissenters’ Admission into the Universities p. 108

- 10. Ingilby’s Motion on the Malt-Duty p. 109

- 11. Cobbett’s Motion on the Malt-Duty p. 110

- 12. For Removal of the Bishops from the House of Lords p. 110

- 13. Minority on Third Reading of the Poor Laws’ Amendment Act p. 111

- VIII. List of Placemen, Pensioners, Sinecurists, Grantees, &c. in the First Reformed House of Commons p. 111

- IX. Future Policy of the Tories, as exemplified in Extracts from the Speeches of the Duke of Wellington, Sir R. Peel, &c. 117

- X. Whig Claims to National Confidence p. 120

- XI. Return of the Annual Expense of the Militia, Yeomanry and Volunteers in each year since the Peace p. 121

- XII. Proportion of Churchmen and Dissenters in 203 Towns and Villages in England; from local Returns transmitted to the Congregational Union p. 122

- XIII. Obituary and Corrections of the last Edition of The Black Book p. 122

- XIV. List and Characteristic Additions of the Members of the Anti-Reform Administration p. 124

[a]

[b]

TORY MISRULE. “The People would be quiet if let alone, and if not there is a way to make them. There shall be no Reform so long as I hold a station in the Government. ”. Duke of Wellington, Nov. 2 1830.

[i]

APPENDIX

to the

BLACK BOOK:

an exposition of the

PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES

of the

REFORM MINISTRY AND PARLIAMENT:

THE CHURCH AND THE DISSENTERS;

CATASTROPHE OF THE HOUSE OF LORDS;

and

PROSPECTS OF TORY MISRULE:

with tables of ecclesiastical and election statistics, and corrections of former editions of the black book.

“His Grace is favourable to Reform—he must be favourable to Reform;—‘There stands his Grace between two bank directors!’ ”—“Not content with promises for the future, which I think you will find vain and unsubstantial, they refer to their past acts as proofs of their attachment to Reform; yet I think I shall demonstrate to you that they were only proofs of their inability to resist Reform.”

—Lord John Russell’s Speech, Totness, Dec. 2, 1834.

BY THE ORIGINAL EDITOR.

SIXTH EDITION,

with

THE ‘CRISIS’ and a CHARACTERISTIC LIST OF THE

ANTI-REFORM GOVERNMENT.

LONDON:

PUBLISHED BY EFFINGHAM WILSON, ROYAL EXCHANGE.

MDCCCXXXV.

[ii]

LONDON:

printed by w. marchant, ingram-court, fenchurch-street.

[iii]

THE ‘CRISIS.’↩

Since the publication of the first edition of the Appendix the Tory Ministry has been completed, and a list, with their characteristic additions, is placed at the end of the Addenda.

Failing to draw in the Stanley party, sir Robert Peel has madly thrown away the scabbard and identified his government with the Rodens and Knatchbulls—the Orangemen of Ireland, and the high churchmen of England. Acts, not evasive addresses, proclaim the policy of the new Administration; but happily the means are at hand to crush in embryo the Hydra visitation.

Electors have only to ask themselves,—For what was the late Ministry abruptly dismissed? For what is parliament prematurely dissolved? Is a Peel Cabinet, or a Peel House of Commons, likely to be more reforming than either? Is experience no longer to be our guide, but professions, rather than deeds performed and principles avowed, to be taken in earnest of the future conduct of statesmen? In so plain a matter there can be no mistake. Our course, in the approaching struggle, is as open as the heavens that cover us, and Reformers cannot possibly misunderstand each other or be misled by the common enemy they have to combat.

The base delusion sought to be practised by a perfidious branch of the Press has been repudiated with scorn by the Minister it was meant [iv] to serve. ‘Measures not men!’ croaked the wily Deceivers. But what said sir Robert Peel at the Mansion-house? Hear him!—

“I do not agree with the views of some persons, who are disposed to overlook the men who constitute a Government, and regard merely the measures they propose. I do not believe that any Government can be stable or permanent which does not possess public confidence. I do not believe that a cold approbation of measures, after previous scrutiny, will avail for the support of a Government, without reference to the heads which conceived and the hands which are to execute those measures.” —December 23, 1834.

Upright man, but mistaken and incapable Premier, we accept the test with thankfulness. But by what strange perversion of moral reasoning it has been sought to destroy the sole foundation of human judgment and confidence! In all the affairs of life to what do we trust their successful issue but to the ‘heads’ and ‘hands’ that conceive and direct them, and which past experience has accredited?

Upon this principle, Electors, the King seeks your opinion of his new servants. Let him have it with firmness and alacrity. There is now an end of mystification; the instruments of his will are before you; save one, they are to a man the opponents of the Reform Bill—the Ministry of the Six Acts—the Spy System—Tithe Massacres—Religious Intolerance, and European despotism. For the love of our species avert this threatened plague of nations! At your bidding the spectre of Misrule will disappear. Sir Robert is carried along by a torrent he cannot control, and will gladly withdraw from his irksome position when commanded by the voice of his countrymen. Let it be loudly and intelligibly expressed. By your moderation, discernment, and promptitude, place on record one more proud testimony to the excellence of representative institutions.

Select carefully the organs of your sentiments. Let eternal hostility to Tory domination be the first sine qua non of your suffrages. To carry out the principles of the Reform Acts, so as to purify, not to destroy, our institutions, another. These are cardinal points, and embrace in their full development Church Reform, Corporation Reform, Law Reform, Equality of Civil Immunities among all [v] classes of religionists; with the remaining et ceteras that constitute the roll of national grievances.

The agitation of constitutional novelties we deprecate. There will be time enough for that hereafter, if need be. At the existing crisis it would create divisions, by which the concentrated force necessary to destroy the mischief hatched by Bishops and Courtiers would be weakened. Pledges, however, ought to be demanded to the extent we have indicated. All untried men ought to be pledged, and all tried men, if still suspected; but surely it cannot be necessary to pledge those who have been tried and approved. Pledges are to guarantee the future; but what better guarantee can we have than past and accepted services?

With these intimations, which some perhaps may deem obtrusive, we commit our countrymen to the strife. That each and all will do their duty, regardless of intimidation, corruption, and base Journalism,* we fear not; and long before the vernal equinox, the black cloud which has gathered over the freedom and happiness of Britain be dissipated!

January 1, 1835.

[vi]

[vii]

ADVERTISEMENT TO THE FIRST EDITION.↩

The design of this Appendix is to supply omissions, and to correct and complete up to the present period the mass of information contained in former editions of The Black Book, especially the last edition, published in 1832.

The preliminary chapters were written prior to the change of administration, and comprise an exposition of the principles and practices of the Reform Ministry and Parliament up to the period of the former’s dissolution. They also embrace a brief elucidation of the important interests at issue between agriculture and commerce—the Church and the Dissenters—the rich and the poor—our fiscal administration—and other great questions which are long likely to engage public and parliamentary attention. The remaining chapters relate to the recent change of ministers and its probable consequences, and the purport of which is sufficiently indicated by their titles. In the Addenda is a collection of statistical information, explanatory of subjects of previous discussion, the existing state of the representation, and the character and composition of the Reform Parliament. Much of this detail is of permanent interest, and will also be found valuable for reference in the event of a general election.

The British constitution is in a dilemma, and in the chapter on the ‘Catastrophe of the House of Lords,’ we have taken the ‘bull by the horns,’ by shewing where the chief difficulty lies and the mode of extrication. Changes of ministers are only convulsive efforts to avoid an inevitable conclusion. Our discussion may be thought premature; but surely two years are long enough for carrying on a national deception which every one sees through, though its open avowal is by some deemed inexpedient. What the nomination boroughs were, the Peerage is—the national grievance—and until it be redressed—until the second estate of the realm be brought to harmonize with the Reform Parliament, we shall continue to vibrate on the [viii] agitating eve of a collision, the issues of which no man can gather up. It is not an unforeseen difficulty, it was foretold by Canning, Peel, and even Wellington, if not in words in idea, that the reform of the Lords would be an unavoidable consequence of the reform of the Commons.

Respecting the question which now fixes public attention, namely, the conflicting claims of the ‘Ins’ and the ‘Outs’, there seems little difficulty. The point at issue is simply this—Shall the people repose confidence in those who adopt reform from principle, or in those who repudiate it on principle. In private life the election would be promptly made. When men walk into danger with their eyes open—when they sin against knowledge—it is justly deemed a sign of weak or deranged intellect. He is a foolish shepherd who places over his flock a dog accustomed to bite sheep; nor less would be the fatuity of the people, if they trusted those who have always made them their prey, not watched over their welfare. Professions of reform will always be abundant. Who so base indeed as to profess otherwise? But the kind of reform makes all the difference. What a Radical deems reform, a Conservative deems destructive. It is not phrases but acts we want. To learn the future we must look to the past. What the Tories have been, we have still too many painful remembrances—an imperishable Debt, and a ‘dead weight,’ which alone, since the peace, has swallowed upwards of one hundred millions of the fruits of industry. Can this be forgotten by the toiling hives of Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Scotland? The Whigs are not without reproach; they have been timid in concession, but they have been great benefactors. In truth, when they gave us the Reform Bill, they gave us all, or nearly so, the rest being only a question of time in taking possession; the title-deeds and the power were put into our hands, and perhaps we have been too generous in consulting the convenience of the outgoing tenants!

For our parts we are always for choosing the least evil and the greatest good. On this principle we prefer a Whig to a Tory, and a Radical to either; but in our anxiety to serve a relative rather than a neighbour, we will not play the game of the common enemy of both.

Never since political strife began was there so outrageous an attempt as that which is now being made, on the credulity of the English nation. Those who have always been the foes of civil liberty, those who considered reform as synonymous with ‘revolution,’—who even thought the disfranchisement of East [ix] Redford a dangerous innovation on the constitution—are now put forward as the people’s best friends, as the fittest instruments to select to work out the consequences of the Reform Act which they reviled, opposed to the utmost, and dreaded as the harbinger of that retributive justice their misdeeds had so long provoked. The juggling of St. John Long, of Mahomet, or any other successful practiser on popular folly, was nothing to this, and we shall be curious to see how far it will succeed in a community heretofore distinguished by good sense and discrimination. To the dialectics of the shallow sophistry which it is sought to cram down by mere force of daily and impudent iteration, no answer is requisite, for its dupes and its authors must be alike contemptible.

We are obviously in a ‘crisis,’ though it may be denied by those who are unable or unwilling to comprehend the social elements in conflict. It is a crisis, too, into which the country has been deliberately, if not wantonly, precipitated. It is now established on unquestionable authority that no divisions existed in the late Cabinet likely to terminate in its dissolution. Lord John Russell, in his speech at Totness (Dec. 2nd), says pointedly, that ‘at no time was there the prospect of more unanimity than when the Cabinet was dissolved.’ Ministers were occupied in preparing plans of reform for the next session of parliament when they were abruptly dismissed, and he must be blind indeed who does not see the cause and the object when he sees the men by whom they have been supplanted. But Englishmen are great on great occasions, and they will not fail in the present emergency. Their old enemy is once more in the field; all the unclean things are collecting together to make a stand for the remnant of Corruption—for a rich sinecure Church, and the close Corporations that have so long rioted in the abuse of the trust property of the poor. It will be the Battle of the Bishops, for it is at their instigation, aided by the corporators, that the new war has commenced between the government and the people of England.*

[x]

It is an event for which we were certainly unprepared. We had consigned the Tory plunderers to the ‘tomb of the Capulets,’ as will be seen from the first page of our publication; having lost ‘the mind and motive’ force of the country, having exhausted all their arts of imposture, we never thought they would have the effrontery to re-appear in a public capacity. But their reign will be short; if not quietly disposed of by our parliamentary representatives, they will be crushed by the uprising of national execration at a general election. Meanwhile it will be interesting to observe their movements. They have already tried to pass themselves off as Reformers, but that is too clumsy a cheat to be long persisted in, and, thanks to the Reform Acts, there is no chance for gagging Bills, Habeas Corpus Suspension Acts, nor Seditious Meeting Bills:—therefore our opinion is that they will be driven to their old tricks, to try to alarm the proprietary of the kingdom, or to divert attention by a war about Belgium or Turkey, under pretext of maintaining national honour and preponderancy;—they will say nothing about the poor curates of England, nor the wretched peasantry of Ireland; their fears—pious and loyal souls!—will be all for the ‘interests of religion,’ the safety of the Monarchy, and the three estates; meaning thereby, as every one knows, tithes, pensions, cathedral sinecures, charity plunder, and a renewed lease of misrule!

These are certainly stale devices of the Pitt and Castlereagh system. Still, when one recollects the remark of Mr. Hume on the repeated success of similar arts of deception in all ages, and when, too, one sees that feats of ring-dropping, little-go, and other contrivances of fraud, continue daily to be played off with advantage in the metropolis, we cannot be sure that even Peel and his mountebank colleagues may not, for a time at least, meet with a certain degree of encouragement.

But that they will ultimately be driven from the stage there can be no doubt. Reformers are not so infatuated as to let their petty differences give a triumph to their common foe, and thereby lose the grand prize for which they have so long struggled—cheap—alike protective—and responsible government. If they cannot, at the ensuing election, secure the services of the best Reformer they will take the next best;—at all events they will unite and close their ranks against the entrance of the wily, hated, and well-known Tory.

December 15th, 1834.

[1]

APPENDIX TO THE Black Book.

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES OF THE REFORM MINISTRY.↩

The Tories, or, according to their new designation, the conservators of abuses, have become, like the Jacobites, little more than an historical name. The mind and motive force of the country have left them, and it is impossible they can again exercise political power. If they are wise, they will seek obscurity rather than keep alive the remembrance of their misdeeds. They cannot complain that their reign was short, nor dissolution premature. They lived the full natural term of authority, that is, they survived till they fairly sank under the re-active energies of the corruptions they had patronized, and by which their sway had been perpetuated.

If we revert to the state of public institutions, it is manifest they could not have been longer carried on without the corrective of new principles. The seeds of decay had extended to the secondary as well as primary departments of administration. Abuses were not more rife in the church, public offices, and pension list, than in the courts of law and great corporations of the kingdom. Under a pertinacious system of non-inquiry and non-reform the gangrene had spread through the entire body politic. What is more, the Tories had lost their moral influence. A pretended respect for antiquity, a dread of innovation, and other plausibilities under which they had carried on their plunderings, failed to delude the community; it was found that the superstition of toryism, like other superstitions, was bottomed on mere selfishness and spoliation.

The Whigs succeeded under circumstances well calculated to inspire hope and confidence in the nation. First, they had been reared in the salutary school of adversity; with claims to power equal to their opponents, they had been long excluded from the sweets of enjoyment. [2] Of course they entered office with a tempered and even humiliated spirit, and with no little ostentation of devotion to the popular will.

Secondly, they were bound by previous pledges; during a long course of opposition they had placed on record sentiments which they could not belie without the forfeiture of all claim to principle and character.

But the third and best guarantee of their conduct was in the state of the public mind. The people had been awakened to the defects of their institutions; they were unanimous and energetic in the determination that no pretext, no factious illusion, should avert their efficient reformation. While this spirit lasted, the Whigs could not swerve from the path of patriotism without endangering their official existence; and it was only as popular excitement subsided that their own zeal in well-doing abated. That such a change has come over them we will show by their acts; but before we do this, we shall advert to some leading measures as illustrative of the principles of whig government.

We pass over such acts as had no characteristic feature about them, and the course of which would have been similar whether directed by a whig or tory administration. Such were the renewal of the charters of the Bank of England and East India Company. The only thing we shall remark, on the agreements concluded with these great public bodies, is that ministers made an improvident bargain for the public; that they conceded advantages to these corporations, (especially to the Bank in the legal tender clause,) for which they ought to have obtained a higher price. That this was the case is proved by the rise in the price of the stocks of the two companies immediately after the arrangements had been completed. As respects the Bank, too, the opportunity ought not to have been lost of placing the whole trade of banking on a better foundation—of securing a currency of unchangeable value—and obtaining for the public not only the profit, but the security of a national circulation, issued under the authority and guarantee of the state.

The settlement of the West-India question is another great measure of the whig ministers. We pass over the ludicrous part of this business—namely, ministers first proposing to grant a loan of fifteen millions to the planters, and then suddenly transmuting the loan into a gift of twenty millions; let us attend to the principle of this transaction.

Had the planters a fair claim to compensation for the emancipation of their slaves? We say decidedly no. The ground on which the claim has been most plausibly defended is the fact that a vast property in slaves had grown up, if not under the sanction, at least under the connivance of acts of parliament, and that, as this property was about to be destroyed by another act of parliament, the owners of slaves had a just claim to compensation against the legislature, though none against the slaves themselves.

Our first reply to this is, that though acts of parliament had been passed to regulate the slave-trade, none had been passed recognizing a right of property in human beings. Quite the reverse; since it is a well-known maxim of the English law, that the moment a slave touches the British soil he is free, our laws repudiating the idea of a property [3] in the person of an individual. Even a negro enlisting in the British army thereby becomes free by statute, (10 Geo. IV. c. 6, s. 37), as a native of England. Against the colonial legislatures the planters may have had a valid claim to compensation; they may have admitted a property in slaves, but the statute and common law of England are exempt from the opprobrium.

If government was right in its treatment of the planters, it has been unjust towards other classes. We will cite two cases in illustration. Under the authority of the law the great brewers acquired a valuable property in public-houses; by an act of parliament opening the beer-trade the property was destroyed or depreciated, and no compensation was granted for the injury sustained. Prohibiting the beer-houses to retail beer to be consumed on the premises will inflict great injury on their proprietors. Yet, though these houses were opened under the express guarantee of an act of parliament, and the property therein may be greatly impaired by another act of parliament, no compensation will be given to the owners for the loss they have suffered.

The property in newspapers has become a great property; it has been created under, and its value may depend on the continuance of the existing stamp laws. It is impossible to foresee what might be the effect of the repeal of the stamp duties, but whatever this effect may be, however greatly newspaper property may be depreciated thereby, we will venture to say the owners would neither ask nor obtain indemnification.

Why ought such different measures of justice to be dealt to the different classes of the community? We can only ascribe it to the aristocracy still predominant in the government. Members of the House of Commons, members of the Cabinet, were interested in the slave question; they were owners of slaves, and so their losses must be compensated! It was not, therefore, for the maintenance of a principle, nor to do an act of impartial justice, but for the maintenance of a caste, that a permanent encumbrance has been entailed on the country of upwards of £600,000 a year,—a sum equal to the taxes on knowledge, and one-tenth of all the money levied for the relief of the poor of England.

The same selfish policy, the same devotion to aristocratic interests, maintains the discriminating duties between East and West India produce, by which the people of England have been taxed four millions annually for the benefit of the trans-Atlantic planters.

An injustice or abuse ought to be abated without compensation. It is contrary to law, as well as reason, that a man should profit by his own wrong-doing. But the Whigs have been constantly doing violence to this principle; they have not sought to reform, but to buy up the fee-simple of abuses at their full value. They have sought to change, not lighten the burden. An overgrown salary has been commuted into a superannuation, and a sinecure into a pension. The maxim acted upon is, that whoever has once had the fingering of the public money shall for ever after be maintained out of the public purse. It is the principle of the poor-laws; let a man obtain a settlement, and he thenceforward [4] claims support from the parish, and let a placeman once get into a government office, and he immediately and for ever sets up the pauper’s claim of being fed and clothed at the charge of the community. Some pensions have been granted on the most objectionable practice of the poor-law administration—namely, the allowance system. We have before us a parliamentary return of persons who receive compensation allowances for the loss of their offices until otherwise provided for; that is, while out of work they shall receive something less than full wages. According to this rule we are now maintaining a mass of tory ex-placemen. Mr. Goulburn receives £2000 a year; Mr. Croker, £1500; Mr. Planta, £1000; Mr. Courtenay, £1000; with many others. The condition on which all these pensions are received is that when they hold offices—that is, get into full employment—their pauper allowances shall cease. But why did not the Poor Law Bill abolish state allowances as well as parish allowances to the able-bodied but unemployed poor. Is it not as reasonable that John Wilson Croker and William Goulburn should have made provision for the vicissitudes of life out of their earnings as Jem Styles and Matthew Dawson?

In their Judicial Reforms the Whigs have gone on the tory maxim, that the holders of sinecures in the courts of law shall receive full pecuniary compensation. But we must protest against its justice; we can never admit of ‘vested rights’ in public abuses; we can never admit that the holders of life or reversionary interests in abuses in church or state are entitled to their full yearly value like the holders of a copyhold or freehold estate. But this favoured class seem even exempt from the changes in the value of property to which other classes are liable. Sinecures, whether lay or spiritual, are no longer sacred in public estimation—they are depreciated in value—they are, in fact, exposed to entire confiscation by the progress of opinion; yet they still continue to be bought up by government at their full nominal worth, in lieu of being extinguished by a compromise or dividend. In this way the great legal sinecures held by lord Ellenborough, the duke of Grafton, and others, ought to be got rid of. But the late reforms in the Court of Chancery have established a mischievous precedent. The monstrous sinecures of £11,000 a year, held by the rev. Thomas Thurlow, were purchased by an equivalent life-annuity payable out of bankrupt estates. The purse-bearer to the lord chancellor, and other officers in the court, were compensated in a similar manner. Lord Brougham received, as an equivalent for the loss of a portion of his sinecure patronage, an addition of one-fourth part to his retiring pension, making it £5000, in lieu of £4000, the highest sum paid to his predecessors.

Lord Brougham is a bitter enemy to the Poor Laws, as encouraging idleness and improvidence; but why does he countenance the application of principles to himself which he reprobates when applied to the less instructed portion of society? What is his pension but a compulsory rate levied on the community as a provision for old age, a large family, or scarcity of employment? These are, in truth, the very pretexts on which it has been justified. By a loss of patronage it is assumed his [5] lordship has not the same means of providing for his children, and his pension is deemed a provision to fall back on in old age or when unemployed. But surely this “great Westmoreland pauper” might provide for the casualties of life out of his enormous income as well as the poor man out of his wretched pittance. As to absolute want of employment there does not appear much to apprehend, as lord Lyndhurst has overcome that difficulty by descending to a chief-justiceship after being chancellor; or why not even descend to practise again at the bar, after the example of chief-justice Pemberton.* At all events there seems little need of a pension: the practice of granting pensions to ex-chancellors is one of the excrescences of the “Pitt and plunder” system, and ought to have disappeared with the first session of the Reformed Parliament.

By-the-by we might as well remark here on the enormous salary awarded to the lord chancellor by his whig friends, and which his lordship, up to this time, has condescended to receive. We do this without any personal ill-will, for we will readily admit no one deserves to be better paid than lord Brougham. But we look to principle and former professions. On examination before a parliamentary committee lord Brougham remarked on the almost impossibility that some of the tory ministers should not have been favourable to the continuance of the late war, seeing it added so enormously to their official gains. Lord Eldon was cited as an instance. Upon an average of three years during the war his lordship’s net income was £19,233, and in one year, 1811, it was £22,737. (Parliamentary Paper, No. 322, session 1831.) Lord Stowell lost £8000 a year by the cessation of hostilities as judge of the admiralty court. Even the king lost by the peace, as he had no longer the plunder of the droits of the crown and admiralty to supply his extravagance. It is inconceivable men would act so detestable a part with their eyes open, as to continue the miseries of war for mere official spoil; yet as lord Brougham most justly observed, “human frailty operates so, that without stating to ourselves the points we are erring upon, our interests work upon us unknown to ourselves.”

Now is lord Brougham more favourably circumstanced than his predecessor? Is he not surrounded by the same interest-begotten motives of action? By the establishment of the Bankruptcy Court his duties are considerably less than former chancellors; yet, allowing for the change in the value of money, his emoluments are greater than the average emoluments of lord Eldon during the war, and he has a retiring pension equal to the salary of the president of the United States of America. It is hardly possible, therefore, that he can see great defects in a system by which he so greatly profits, or be zealous in the reform of abuses. Hence his procrastinated, illusive, and abortive legal reforms. During the four years of his chancellorship not more has been effected than would have been effected under a tory or any other administration. The defects in our judicial system, and the chaos of absurdities in the statute [6] and common law of the realm, continue unredressed. Even the Court of Chancery is still pre-eminent for delay, cost, and circuity. And why not disintegrate the mass of incompatible duties in his lordship’s own office, by separating judicial from political functions, and removing the opprobrious farce of appealing from lord Brougham on the bench to lord Brougham on the woolsack? A love of patronage, of power, and emolument, are the lurking motives.*

In their Ecclesiastial Reforms the Whigs have been singularly unsuccessful, and the second session of the reformed parliament has terminated without any substantial improvement being effected either in the Irish or English branch of the United Church. It would occupy too much space to exhibit at length the abortions in principle and detail that have been propounded, still it is essential to give the reader an outline of what has been proposed, as illustrative of the views of ministers on church reform and indicative of future proceedings.

The Act (3 and 4 Will. IV. c. 37.) for regulating the temporalities of the Irish Church was the chief measure of the first session. By it the number of bishops is reduced from twenty-two to twelve, by the union of sees as the present incumbents die off. After the death of the present incumbents also, the enormous revenues of some of the sees are to be reduced; that of Armagh from its present amount of £14,500 to £10,000; that of Derry from £12,000 to £6,000; and all the other sees which may be worth more than £4000 to that sum. The exaction of vestry cess is abolished. So is also that of first fruits, in the stead of which there is to be imposed upon all livings above the actual yearly value of £300 an annual tax, varying in its rate according to the value of the living. Lastly, the leases of bishops’ lands are to be converted [7] into perpetuities, by which it is supposed a sum of £1,200,000 (it was originally calculated at three times that amount) will be realized. The fund arising from these prospective reductions and savings—for mind, it is all in future—is to be vested in commissioners, consisting of six prelates of the Irish Church and the Lord Chancellor and Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, and under their direction it is to be applied to the augmentation of small benefices, the building of churches and glebe houses, the meeting of the expenses hitherto defrayed out of the vestry cess, and other purely ecclesiastical objects. The fund so created it is calculated will ultimately yield a revenue of £155,000 a year.

Upon this first measure of reform two observations may be made. 1. It effected (with the exception of the see of Derry) no immediate reduction in the enormous revenues of the Irish clergy. 2. With the exception of the vestry cess, amounting to about £35,000 a year, not a single farthing is saved to the community; an enormous sinecure church establishment is still left to levy the same amount of revenue from the industry and property of Ireland. So far, then, as the people are concerned, the reform is totally valueless; it saves nothing for the poor, for education, nor for local improvements.

In lieu of a measure of this sort a very different proceeding was demanded. A crisis had happened in the affairs of Ireland; by what may be termed the natural course of events, the clergy had lost their tithes, and the church, instituted for the benefit of the people, had become alien and useless to them. Here, then, was an opportunity for getting rid of the entire grievance. Abolish the Irish Church as a national establishment; share among the clergy the remnant of property which events had left to them; let them have life stipends out of the produce of the bishops’ and other church lands. In lieu of tithe let a land-tax be levied for the maintenance of the destitute, for education, and for the extinction of those territorial rights which are the great obstacle to the reclamation of the bogs and wastes of Ireland.

By such a plan of reform the ecclesiastical establishment, which has been the principal source of impoverishment and civil strife, might have been made the great instrument for improving and tranquillizing the country.

Two other acts were passed relative to the Irish Church; one for effecting a compulsory composition for tithes payable by the landlord, and the other empowering government to make advances to the amount of one million to such of the clergy as had not been able to recover the tithes due to them, to be repaid by five annual instalments. The landlords are now the parties from whom the repayment of these instalments may be demanded, who have of course their remedy against occupiers of the soil. It is not improbable the money advanced to the Irish clergy will never be repaid except out of the pockets of the people of Great Britain. But we must leave this to come to the schemes introduced last session for the extinction of tithe.

First it was resolved, before any final arrangement took place, the law [8] itself should be restored, and the right of the clergy vindicated by enforcing the payment of tithe. In the execution of this preliminary essay, that noted person the Right Hon. E. G. Stanley most signally failed. After bringing into play all the resources of his vast genius—after employing horse, foot, and artillery, to collect the pigs, poultry, cattle, and chattels of the peasantry, the most energetic of secretaries could only raise £12,000, and this after an expenditure of £60,000.* Failing in this project, the next position assumed was that whatever might be the fate of tithes, the landlords had no right to a farthing of them. This was lord Althorp’s own explicit, firm, and decided declaration. Mr. Littleton followed with his celebrated resolution of the 20th of February, for the conversion of tithe into a land-tax, payable to the crown and redeemable by the landlords, the produce of such redemption to be invested in land for the benefit of the clergy.

To this proposition the objections were weighty and manifold. First, the policy of tying up in mortmain a mass of real property in the hands of the church or government, was not sanctioned by the experience of history. Secondly, the making the clergy stipendiaries of the state would not tend to elevate their office in public estimation, and gave a sanction to some of the popular notions respecting them. Lastly, it was not likely many of the Irish landlords would have money to spare to redeem their tithes, poor as they were known to be, and burdened as their estates mostly are with mortgages and settlements.

To surmount these difficulties the Great Agitator came forth, July 30th, with his famous proposition for at once giving a bonus of 40 per cent. to the landlords on condition that they would, in place of their tenantry, charge themselves with the payment of the remaining 60 per cent. of tithe. The plan was that the clergy should abate 221/2 per cent. of their full due,—namely, 21/2 per cent. for the expenses of collection, and 20 per cent for better security. Every incumbent therefore would receive 771. 10s. certain in lieu of £100 nominal income. Of this 771. 10s. the sum of £60 would be paid by the landlord, and the remainder, 171. 10s., be charged on the consolidated fund, that is, on general revenue of the empire. Ultimately, indeed, it was held forth [9] that the difference of £17 was to be paid out of what is called the Perpetuity Fund, that is, the fund already alluded to, arising from the sale of bishops’ leases in perpetuity; but as this fund is not likely to be realized during the present generation, it may be concluded that the tax-ridden people of England and Scotland would be saddled with the payment of nearly one-fifth of the tithes of the Irish clergy!

The plan we have last indicated is that which passed the House of Commons, but was rejected by the Lords as too unfavourable to the Church; but a plan more favourable to the Church and less favourable to the people is not, in our opinion, likely to be again submitted for their acceptance.

That it was favourable to the clergy may be easily illustrated. By the defection or hostility of the people tithe had become extinct as a property, as much so as if it had been swallowed up by the sea or an earthquake. Under such circumstances were not 771/2 per cent. a most bountiful equivalent? In our opinion it was too much. Few persons would give £77 for £100 tithe even in England, to be saddled with its insecurities and the expenses of collection. Many landlords would gladly accept £77 certain, indisputable, and in perpetuity, in place of a nominal £100 of their rents. Whether the Irish clergy were entitled to anything may be doubted. They had lost their property by the course of events, and how many other persons have lost their incomes by the vicissitudes of the times without receiving compensation? To wit, those who have been ruined or injured by tamperings with the currency, the Bank Restriction Act, and the reduction of the Five and Four per Cents. Stock of the National Debt. Government showed no sympathy for the sufferers in these instances, though it was, in fact, the author of their misfortunes. We repeat, then, that the tender to the Irish clergy was most liberal—more liberal, we are sure, than will ever be again offered.

Let us next advert to this plan of ecclesiastical reform as it would have affected the community. It is of importance to examine it with attention, as it may be made the foundation of ulterior projects for the extinction of tithe in England.

Two-fifths of the tithes were to be at once swamped in a bonus to the landlords. This was the most indefensible part of the scheme. If there were any point on which all men were agreed, it was on the fact that, come what might, no portion of the tithe ought to devolve to the owners of the soil. This was the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s own explicit and apparently unchangeable declaration. Next to the clergy no class was so deeply interested in the settlement of the tithe question as the landlords. It gave value, peace, and security to their possessions. In lieu of a bribe they ought to have made a sacrifice. But the source whence the bribe was to be taken outrages belief. It was not to be taken from the vast possessions of the Irish Church, but to be charged on the general revenue of the empire. Of the £40 out of every £100 to be given to the landlords, nearly one half was in great part to come out of the pockets of the dissenters of England and presbyterians of [10] Scotland. Here was ecclesiastical regeneration with a vengeance! In lieu of the reform of the rich sinecure church of Ireland opening new sources of public revenue, it would have entailed additional burdens on the community. The question of the secular appropriation of the surplus wealth of the church was perverted into a question for appropriating more money for its maintenance—and of which a whig aristocracy, who had with alacrity adopted this new scheme of public spoliation, and who are among the principal landowners of Ireland—and the rest of an absent proprietary, who had been the chief causes of the miseries of the country—were to have the sole benefit and advantage!

One of the most objectionable measures of last session—Poor Law Bill excepted—is the Civil Offices Pension Act. This act is founded on an act passed during the odious administration of lord Castlereagh. In 1817 the call for retrenchment was loud and unceasing, and in order to silence the popular cry a committee of the House of Commons recommended that certain of the most obnoxious sinecures should be abolished. But as this took away a portion of the corrupt matter at the disposal of the minister, it was proposed that the crown should be empowered to grant certain equivalent pensions to its adherents in lieu of the abolished sinecures. Accordingly the 57 Geo. III. c. 67, provided that all the chief and subaltern officers of government, from the first lord of the treasury down to the clerk of the ordnance and first and second secretaries of the Admiralty should be entitled to retiring pensions, varying from £3000 to £1000 per annum.

This, it must be confessed, was an odd mode of economical reform. The sinecures were abuses, and ought to have been swept away without placing another equivalent abuse at the disposal of the crown. The principle assumed was that sinecures were the property of our hereditary legislators and their dependents, and as this property was taken from them they had a right to be provided for in some other way; that either as sinecurists or pensioners they were entitled to a perpetual maintenance from the public!

Upon this bill of 1817—so base in its origin and so indefensible in principle—the Whig act of the present session for granting pensions to themselves is founded. The Act 4 and 5 Will. IV. c. 24 provides that the first lord of the treasury, the secretaries of state, the chancellor of the exchequer, first lord of the admiralty, president of the India board, and president of the board of trade, may each claim £2000 a year pension after two years’ service at one or different times; that the chief secretary of Ireland and secretary at war may claim £1400 a year after five years’ service, and that joint secretaries of the treasury, vice-president of board of trade, under secretaries of state, first and second secretary of the admiralty, and secretaries of India board, may each claim pensions from £1200 to £1000 for terms of service, varying from five to ten years.

Neither the public press nor the radical members of the House of Commons appear to have taken notice of this extraordinary measure [11] of a reform ministry. We shall, however, offer a few observations, first on the extravagance of this provision, and, secondly, on the principle of placing such a power of rewarding the high and efficient officers of government in the hands of the crown.

According to the act, the first lord of the treasury, after two years’ service, may claim a pension of £2000 for life, and the president of the board of trade a like sum after the same term of service. Supposing now these officers forty years of age, and that they retire from office after two or three years and live to the age of eighty they will receive, exclusive of interest, £80,000 of the public money, or £40,000 for each year of actual labour. A pretty reward this to lord Melbourne or Mr. Poulett Thomson for submitting for a couple of years to the drudgery of public life, exclusive of their official salaries and patronage while in office, and which we should have thought ample remuneration.

But why should the power of rewarding public services be vested in the crown, and not in the House of Commons? It is plain enough that it is only the favourites of the court or of the ministers that will receive pensions under this act. No servant of the people, however necessitous, will ever be benefited by it—only the parasites of power. It is in fact bribes for servility, so much additional influence to the crown, and a further provision for titled pauperism. Lord Brougham, however, concurred in the measure as well as the duke of Wellington, and the chief objection to it entertained by earl Grey was, that “it did not sufficiently enable the crown to reward public functionaries.”

There is another observation connected with this extraordinary provision of the Whigs,—namely, that it holds out a temptation to ministers to desert their employment without reasonable and adequate occasion. We do not mean to insinuate that the chance of £2000 a year for doing nothing was the cause of the retirement of lord Grey, Mr. Stanley, and sir James Graham; we do not mean to say that they acted from the same unworthy motives that lord Brougham says the paupers do—that they prefer one-half or one-third wages in idleness rather than whole wages and industry; still, as the same learned personage remarked, selfish motives do exert such an unerring influence over human conduct, unknown even to the parties themselves, that it is impossible to say to what extent they may have influenced the individuals mentioned. It cannot be denied that during last session ministers were always ready to withdraw from office; indeed, having made such a comfortable provision for themselves, and having placed in lucrative appointments their relatives and dependents, they had scarcely any motive longer to undergo the toils and anxieties of official life. They had, as the late premier recommended the bishops to do, put their ‘houses in order,’ and were prepared for the worst. The threat of retirement was really the talisman by which they governed the country. If the independent portion of the House of Commons was likely to prove refractory, a ministerial ‘strike’ was held in terrorem, which instantly procured implicit obedience.

Now to those honourable Members who really consider the services of [12] lord Althorp and colleagues essential to the government of this great empire—a necessity we confess we do not ourselves perceive—we would vouchsafe a word of advice. Why do they not take away from ministers all temptation to retirement?—why do they not obtain the repeal of an act which holds out a direct inducement to withdraw from office, and apply to them the same principle they are seeking to apply to the poor, that those who do not work neither shall they eat—at the public expense!

As our purpose is not to present a detailed history of the Whig Ministry merely to illustrate principles, we shall only indicate minor delinquencies. Of this sort was the grant of a pension of £2000 a year to Mr. Abercromby. The appointment of this gentleman to a Scotch sinecure judgeship of the Court of Exchequer, just on the eve of its abolition, was itself a mere job; and then on the reduction of the court to settle the honourable member on the country for life was an indefensible mode of providing for a friend totally unworthy of a reform government. Of the same character, or worse, was the creation of a new office for Mr. Macaulay—his father and other relatives having before been provided for—with a salary of £10,000 a year, and an ample retiring pension after four or five years service, as a means of paying him for half a dozen clever speeches, reviews, and party pamphlets. Not less objectionable was the appointment of sir John Byng to the governorship of Londonderry—a sinecure of £1200 a year. The Russo-Dutch loan and the guarantee given to Otho, king of Greece, were measures of questionable policy, by which a serious burden and responsibility have been imposed on the country. Then, one cannot forget their defence of naval and military sinecures—their opposition to a revision of the pension list—to the abolition of flogging in the army—to naval impressment—to the repeal of the septennial act—the stamp duties on newspapers—and the introduction of the ballot.

The measures on which the Whigs may justly pride themselves are their Reform Bill, their economical reductions in the public expenditure, their improvement of the constitution of the Scotch Burghs, and their foreign policy. They have also instituted many salutary inquiries into the civil and judicial administration of the country. But their foreign policy, next to the reform bill, is their proudest boast. They have not only preserved peace—so essential to the thorough reform of our institutions and the progress of constitutional liberty abroad—but they have severed the country from its tory connexions with the continental despotisms, and united her destinies to the free governments of France and the Peninsula. The union of the naval power of Britain with the military power of France is the guarantee of peace, or, if war should come, of victory against Tyrants!

[13]

CHAPTER II.

THE PLOUGH AND THE LOOM.↩

There is obviously a strong disposition in ministers and the reformed parliament to show special favour to agriculture. On the opening of the late session his Majesty is made to lament “the continuance of distress amongst the proprietors and occupiers of land.” All the more important measures subsequently introduced, as the repeal of taxes on husbandry and the reform of the tithe and poor laws, appear to have been deemed chiefly valuable as modes of rural relief. Now an important question offers,—is there any thing in the present state of agriculture, or its relative importance as a branch of national industry, that fairly gives precedency to the Plough over the Loom? or is the preference merely a feudal prejudice, or selfish desire on the part of the territorial classes to forward those pursuits in which they are most deeply interested?

As to the existence of agricultural distress, that is a condition inseparable from the cultivation of the soil. But that there is general and unusual distress among the farming classes, we deny, and for proof refer to the evidence (not Sir James Graham’s Report) given before the Agricultural Committee of last year. Relative distress will always subsist in agriculture. Farming is and always must be a poor trade. The inducements to invest capital in land are such, that the profits of farming must always be depressed below the profits of commerce and manufactures. This is not the only cause of depression. In England, where two-thirds of the land occupied are held by tenants-at-will, if a farmer’s profits increase, his rent will be proportionately increased. So that, pressed on one side by the greater competition of capital in his employment, and on the other by the increasing exactions of his landlord, it is obvious that he can never enjoy, for a lengthened period, an exuberant state of prosperity.

From this dilemma no protection can save him. Were the price of corn, by restrictions on importation, artificially forced up to 120s. a quarter, his condition would not be permanently bettered. There would still be agricultural distress for him. The exorbitant price of corn would force inferior land into cultivation, the produce of which, owing to the greater outlay in its cultivation, would barely remunerate the grower; so that the occupier would be still only able to obtain a bare [14] subsistence; and as to those occupying the richer soils, they would be reduced to their wonted level by the increase of rents.*

The partial distress of landlords, though it originates in different causes, seems as inevitable as that of their tenants. In Poland, in Russia, in Spain, and in every European community, the landed interest is in a state of pecuniary embarrassment. Every where estates are encumbered by debts, mortgages, and settlements. This, however, is not because their revenues are small, but because they are enormous. It is men of moderate, not of large incomes, that live within them. The former are compelled to practice economy, to look after their affairs, and live according to rule; the latter are exempt from these precautions. George IV. had a million a-year and was constantly in debt, and many of the great landholders, from similar improvident courses, are involved in a like predicament.

It follows that the mere existence of poverty among the proprietors and occupiers of land is no proof of the existence of general agricultural distress entitled to legislative relief. The landed interest has always been the favoured interest in this country; it has been favoured by the [15] progress of commercial and manufacturing industry, and it has been favoured by a most partial allocation of public burdens, and the general course of legislation. After shortly elucidating these circumstances in the progress of agriculture, we will proceed to show that, from changes in society, the time has passed when the landed interest ought to be considered the primary interest of the community.

Notwithstanding the complaints of the decay of agriculture, of farmers living on their capital, and of whole parishes being abandoned from the pressure of poor-rates, there can be little doubt that agriculture has been constantly extending. How otherwise can we account for the comparatively low prices of produce? Population has been steadily increasing, and unless the increase of food had kept pace with the increase of consumers, prices must have been enhanced by competition. It may be alleged that prices have been kept down by importation from abroad, but this is refuted by facts. In the last two years the foreign wheat and flour entered for home consumption have been very inconsiderable. The quantity of foreign wheat and flour kept for consumption in Britain, in the ten years ending in 1820, amounted to 5,206,321 quarters; and in the ten years ending in 1830, it amounted to 5,349,927 quarters.* No great difference. Yet in the interval from 1820 to 1831, population had increased two millions. Now whence has the food been obtained for this vast addition to the number of consumers? Certainly not from Ireland. The imports from Ireland during the last ten years do not exceed on the average 350,000 quarters a-year. But an increase of two millions of consumers requires an increase of at least two millions of quarters of wheat for their sustenance, and that the supply has been obtained is evident from the fact of the steadiness of prices. It may be concluded, therefore, that as this supply has neither been obtained from Ireland nor abroad, it has been obtained from the increasing produce of our own soil.

General facts of this nature entirely negative the idea of the decline of agriculture. They are much more satisfactory than the testimony of individuals; since the last, when honestly given, can only be founded on a limited observance and their own peculiar circumstances. Even witnesses examined by the Agricultural Committee of last year testified to the thriving state of husbandry. In Norfolk, Mr. Wright, an extensive land-agent, bore testimony to the progressive improvement in farming; and in Cambridgeshire and Suffolk the land is as well cultivated as ever, (p. 96.) In Cornwall, Mr. Coode stated that agriculture had improved. In Lancashire, Mr. Reed said (p. 179) the quantity of arable land had increased within the last seven years. Other witnesses testified to the same effect.

No doubt the profits of farming have fallen since the war, but the depression extends to every other department of industry. Taken as a body, in no other country do the agricultural classes enjoy such pre-eminent [16] advantages. Their estates have been fertilized by the wealth flowing from the successful pursuit of commerce and manufactures. They have better turnpike-roads to roll their carriages on, and canals to transport their produce, than can be found any where else. By the help of unrivalled mechanical inventions, they are enabled to buy their wearing apparel, their woollens, linens, silks, and calicoes, cheaper than in any other country. The possession of vast colonies brings within their reach all the choicest luxuries of the earth. Through these and other advantages the English aristocracy has become the richest and most favourably circumstanced in the world. It is remarked of lord Clive, (Universal Magazine, July, 1760,) who had killed himself, that he had £70,000 a-year, and was the richest subject of the king. Many individuals at present have four or five times that income. Foreigners view with astonishment the splendid seats of the nobility, their gorgeous and crowded assemblies, their massive sideboards of plate, splendid equipages, and other indications of territorial opulence!

Mere wealth, however, constitutes only a tithe of the social and political advantages enjoyed by the landed interest. 1. A landed qualification is the basis of eligibility to most civil and legislative functions. Without a qualification in land, no person is eligible to be a member of parliament, a sheriff, a justice of peace for the county, or a commissioner of land and assessed taxes. 2. By the law of entail, their property is protected from the just demands of creditors, when that of persons engaged in trade would be liable. 3. Their possessions are exempt from the legacy and auction duties. 4. A mass of sinecures in church and state are kept up solely for their profit and emolument. 5. In the levy of the assessed taxes and the imposition of turnpike-tolls, special favour is shown to all interests connected with agriculture. Lastly, it is now admitted by sir R. Peel and sir James Graham, that the cornlaws, which levy a tax of twenty or thirty millions on the people, are kept up solely for the preservation of the landed aristocracy as essential parts of the community.

The only drawbacks of the landed interest are tithes, poor-rates, and county-rates. The unfairness of representing these as peculiar burdens on land has been so often exposed, that it appears superfluous to advert to them. For a landowner to complain of tithes, it has been justly observed he might as well complain that his neighbour’s field is not his own, or that he is lord of only 900 in lieu of 1000 acres. For 1000 years at least the tithe-owner has been co-proprietor of the soil, and subject to his claim the landlord has succeeded to his possessions. The lien of the poor is hardly less inalienable; they have always been a charge upon the land, and justly so in return for their services. Then, again, as to the county-rates, the burden properly falls on the landowners, as it is chiefly for their convenience and security that the highways, prisons, and bridges are kept in repair.

Leaving these matters, let us come to the allocation of public burdens. The progress of taxation is a most instructive lesson in the science of government; it shows how a class, enjoying a monopoly of political [17] power, will pervert that power to its own selfish purposes, and to the neglect or depression of all the non-represented interests of the community.

The land-tax is a practical illustration of this truth. This impost has been stationary for a hundred and forty years, notwithstanding the vast increase in the value of landed property. Of forty-nine millions raised by taxes in the thirteen years of the reign of William III. the land-tax furnished £19,174,000. The landowners of that day, therefore bore two-fifths of the whole public revenue, and paid a direct tax to government, which was nominally one-fifth, and might be in reality one-sixth of their entire income.

As the old valuation and rate of assessment of 1692 have been continued to the present, the produce of the land-tax at this day, including the value of what has been redeemed, is the same as it was at the end of the seventeenth century, namely, two millions a-year. But two millions at the former period was about one-fifth of the land-rents, whereas it is now only one-fifteenth. It then formed nearly one-half the public revenue; it now constitutes about the twenty-fifth part. Here, then, is a striking instance of the dexterity with which the landowners have evaded their fair proportion of taxation, and this without being subjected to any countervailing burdens; for it must be borne in mind that when contributing one-fourth of their incomes to the state, they were subject then as now to the additional assessment of tithes, poor-rates, and county-rates.*

Let us now advert for a moment to the continental landowner. More the subject is investigated, and more enviable and favoured will appear the position of the British agriculturist; less ground there will appear for perpetuating the injustice of corn-laws, and seeking relief from existing burdens.

In France, the fonciere, or land-tax, produces about one-fourth part of the entire revenue of the country. The landowners of Austria are supposed to pay at least one-fourth, probably one-third of the entire mass of national taxation. From the statements of Mr. Jacob, it appears that in Hanover, Mecklenberg, Holstein, and Sleswick, the land-tax on the owner’s net profits varies from 20 to 25 per cent. including, however, tithes and school and poor rates, which are generally trifling in amount. In Prussia, the king’s tax on rent is 25 per cent.

It thus appears that in the most improved and civilized countries of the continent, about one-fourth of the whole public revenue is derived from a direct tax on land, while in Britain the land-tax supplies only one twenty-fifth part of the revenue. The landowners of the continent pay about one-fourth of their incomes to government, those of Britain about one fifteenth part.

It is worthy of remark, too, that while the land-tax in this country has been stationary since the reign of William III. it has been in a state [18] of progressive increase on the continent, the cadastres, or valuations, being raised or altered, from time to time, or superseded by new ones.

Having adverted to the privileges, exemptions, and special favour extended to agriculture, let us next inquire whether there is any ground for this preference, either in the superior numbers, industrial character, fiscal contributions, or intelligence and moral power of the agricultural classes: in a word, let us ascertain whether agriculture is, as heretofore considered, the primary, or only the secondary interest of the empire. A solution of these questions will determine the soundness of the policy, which has long been predominant in the legislature, of rendering the interests of the town subservient to the country population.

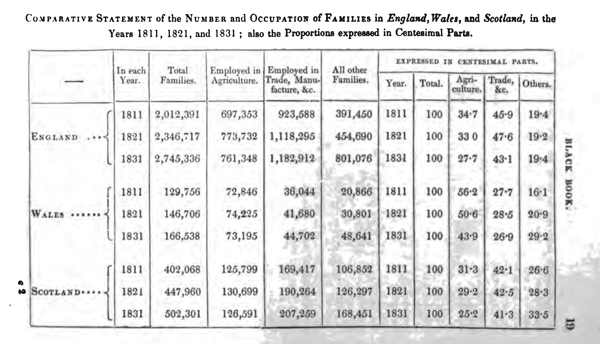

First as to numbers. In England, the proportion of the population employed in agriculture is smaller, perhaps, than in any other European community. In Italy, the proportion of agriculturists to non-agriculturists is as 100 to 31; in France, as 100 to 50; in England, rather more than as 27 to 100. It is a remarkable fact, that the proportion of persons employed in agriculture during the last thirty years has been gradually decreasing, while the proportion employed in trades has been increasing. A similar change in the industrial character of society is observable in Scotland and Wales, as will appear from the following statement of Mr. Rickman, inserted in the Appendix to the Report of the Agricultural Committee.

[19]

Table: COMPARATIVE STATEMENT of the NUMBER and OCCUPATION of FAMILIES in England, Wales, and Scotland, in the Years 1811, 1821, and 1831; also the Proportions expressed in Centesimal Parts.

[To view this wide table in HTML format open it in a new window.]

[20]

Mr. Marshall, in his Statistics of the British Empire, has classed the counties of England into the agricultural, manufacturing, and metropolitan, and given the following table of the increase per cent. in the population of each.

| ENGLAND. | 1801 to 1811. | 1811 to 1821. | 1821 to 1831. | 1700 to 1831. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural counties | 91/2 | 151/4 | 10⅔ | 84 | |

| Manufacturing counties | 181/4 | 201/4 | 221/4 | 295 | |

| Metropolitan counties | 161/4 | 181/8 | 151/4 | 147 | |

| Total | { England | 14⅜ | 17⅞ | 16 | 154 |

| { Wales | 13 | 171/4 | 12 | 117 | |

| { Scotland | 13 | 15 | 13 | 87 | |

| GREAT BRITAIN | 141/8 | 171/2 | 151/2 | 144 | |

From this and the preceding table, we derive two important facts:—First, that the number of persons employed in trade and manufactures far exceeds the number employed in agriculture, and, secondly, that the disproportion is rapidly augmenting. From 1700 to 1831, the population of the agricultural counties increased only 84 per cent., while the population of the manufacturing counties increased 295 per cent. Or, if we limit attention to the more authentic censuses taken from 1801 to 1831, it is obvious how rapidly manufacturing has been gaining on agricultural industry at each decennary enumeration.

So far then as numerical superiority is involved, the loom may claim decided precedency over the plough. This determines the most important consideration, for it is obviously men and not things that ought mainly to decide the course of legislation. But we shall find that trades and manufactures have another point of superiority, namely, in their power to augment the wealth of the community.

There are no authentic data for determining the relative proportion in which the different branches of industry add to the national income. Mr. Colquhoun, with his usual hardihood, has attempted to solve this question. He has given an estimate of the wealth annually realised in Great Britain and Ireland; we give his statement more as a curiosity and the conjectures of a shrewd calculator, than any thing else.

[21]

| £ | |

|---|---|

| Agriculture in all its branches (including pasture) | 217,000,000 |

| Mines and minerals, including coals | 9,000,000 |

| Manufactures in every branch | 114,000,000 |

| Inland trade | 31,500,000 |

| Foreign commerce and shipping | 46,000,000 |

| Coasting trade | 2,000,000 |

| Fisheries | 2,000,000 |

| Chartered and private banks | 3,500,000 |

| Foreign income remitted | 5,000,000 |

| £430,000,000 |

This estimate is chiefly valuable, as shewing the relative productive power of the several branches of national industry in the opinion of an ingenious writer; it is not applicable to existing circumstances, being prepared when the country was involved in war and paper-money, and when agriculture was of far greater relative importance than at present. We have no data for correcting the estimate up to the present. But the superior productive power of manufactures over agriculture may be readily inferred from the obvious facts of the greater number of persons employed therein, and the higher wages and profits realised. These are infallible criteria for determining the amount of wealth annually created in the two branches of national industry. Agriculture barely provides the community with its coarser food; all our luxuries, clothing, domestic conveniences, tools and machinery, shipping, navigation, and vast exports and imports are the results of commerce and manufactures. They have been the source even of agricultural wealth, as well as provided the means for internal improvements and a vast government expenditure.

The third point of superiority we claim for manufacturing industry is, that it contributes in a greater proportion to the public revenue of the country; agriculture not only contributes less to the mass of taxes in proportion to the smaller number of persons connected therewith, but absolutely less as will appear from a representation which appeared in the Times newspaper, April 2, 1834.

Our population in round numbers is 24,300,000, of which one-third or 8,100,000 is engaged in agriculture, and the remaining two-thirds, or 16,200,000, are engaged in other pursuits.

By the English scheme of taxation, the government taxes are for the most part common, and apply uniformly, and are paid by all classes of the community.*

[22]

These taxes may be ranged under the following heads:—

| 1. | The customs and excise, the gross produce of which, for the year ending 5th January, 1833, was | £36,411,482 |

| 2. | The stamp duties, the gross produce of which, for the same period, was | 7,119,892 |

| 3. | The assessed taxes, the gross produce of which, for the same period, was | 5,333,686 |

| 4. | The Post-office, the gross produce of which, for the same period, was | 2,175,291 |

| £51,040,351 |

And the agriculturists being one-third of the population, the proportion of this sum of £51,040,351, which they ought to pay according to their numbers, is £17,013,450: and now let us see what these men actually do pay, and then:—

| 1. | It is quite sure that of exciseable commodities, and those paying the customs’ duties, there is a much greater proportionate consumption in town than in the country; and therefore if the consumption of these commodities by the agriculturists is put down at three-tenths instead of one-third, this will be doing them more than justice, and three-tenths of £36,411,482 is | £10,923,444 |

| 2. | Of the stamp duties at least four-fifths are paid by the inhabitants of towns, and one-fifth only by the agriculturists, and one-fifth of £7,119,892 is | 1,423,978 |

| 3. | Of the assessed taxes four-fifths are paid by the inhabitants of towns, and one-fifth only by the agriculturists, and one-fifth of £5,333,686, is | 1,066,736 |

| 4. | Of the Post-office revenue 11-12ths are derived from the inhabitants of towns, and 1-12th only from the agriculturists, and 1-12th of £2,175,291, is | 181,274 |

| 13,595,432 | ||

| Proportionate contribution, as before stated | 17,013,450 | |

| Difference | 3,418,018 |

So that the agriculturists not only contribute in a small degree to the general revenue, but less by £3,418,018 than they ought to contribute in proportion to their numbers. Yet mirabile dictu! these men are considered the mainstay of the country, and the class for whose interests, in the opinions of a majority of a reformed Parliament, the interests of all other classes should be sacrificed.

Let us advert to the fourth and last consideration—the superior intelligence [23] and moral power of the trading and manufacturing population.

The entire mind and soul no less than the industrial activity and physical power of the community are concentrated in the metropolis and great towns of the kingdom. It is here where institutions of science, of education, and benevolence are founded and maintained. It was here even where civil liberty had its origin, was first claimed and conquered for the entire nation. Among the scattered population of the country, there is as little intelligence as combination for accomplishing objects of general utility. There is hardly any thing like personal independence—from the land-owners down to the farmer and mere labourer, it is a gradation of comparative slavery without the freedom either of thought or action which animates the manufacturer and operative. Hence it is that all great political movements, all great social ameliorations have had their origin and achievement in towns, not in the rural districts. It is commerce and manufactures, not agriculture that have impelled nations onward in the career of improvement. They have been the foundation of the freedom, glory, and magnificence of all great communities, of Tyre, Carthage, and Palmyra, no less than of Venice, Genoa, and the Netherlands. Wherever we find agriculture the sole or predominant industry of a state, there we may be well assured the people are poor and abject in spirit—poor in all the comforts and luxuries of living—women socially and physically degraded—and the whole frame of society debased by tyranny and superstition. Before our eyes, it is so even now in Italy, Spain, Poland, and Hungary. Without Paris, Lyons, and Marseilles, France would have had no revolution,—she would have still groaned under the double yoke of regal and ecclesiastical bondage. Without London, Birmingham, and Manchester, England would neither have had religious freedom nor parliamentary reform, but would have still been in the trammels of a plundering oligarchy and intolerant church.

Pursuing the contrast in its moral and municipal bearings, we are led to similar conclusions. The most degraded part of the population are the cultivators of the soil. Among them it is we find the cases of improvidence, vice, and illegitimate births most numerous. It is not in Leeds, Liverpool, or Manchester, but in the domain of the squire and parson that have been found the worst examples of parochial misgovernment.

But enough: with such facts, moral, statistical, and historical, does it not appear like national infatuation to tolerate the ostentatious imbecillities propounded by sir James Graham and sir R. Peel of the superior importance of agriculture, and that the landed aristocracy is the most essential interest of the community, in whose favour not only the great principle of commercial freedom should be violated, but every man, woman, and child in the country barefacedly and openly robbed!

[24]

CHAPTER III.

THE CHURCH AND DISSENTERS.↩

I.—: UTILITY OF AN ESTABLISHED CHURCH.