THOMAS CLARKSON

The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament (1808)

Two Volumes in One

|

[Created: 1 September, 2024]

[Updated: 29 March, 2025 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament. In Two Volumes. (London: Printed by R. Taylor and co., Shoe-Lane, for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, Paternoster-Row, 1808).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1808-Clarkson_Abolition/Clarkson_AbolitionSlaveTrade1808-ebook-2volsin1.html

Thomas Clarkson, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade by the British Parliament. In Two Volumes. (London: Printed by R. Taylor and co., Shoe-Lane, for Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme, Paternoster-Row, 1808).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Table of Contents for Vol. 1

VOL. I.

- Chap. 1. Introduction—Estimate of the evil of the Slave-trade—and of the blessing of the Abolition of it—Usefulness of the contemplation of this subject - p. 1

- Chap. 2. Those, who favoured the cause of the Africans previously to 1787, were so many necessary forerunners in it—Cardinal Ximenes—and others - - p. 30

- Chap. 3. Forerunners continued to 1787—divided now into four classes—First consists of persons in England of various descriptions, Godwyn, Baxter, and others p. 44

- Chap. 4. Second, of the Quakers in England, George Fox, and his religious descendants - - p. 110

- Chap. 5. Third, of the Quakers in America—Union of these with individuals of other religious denominations in the same cause - - - - p. 131

- Chap. 6. Facility of junction between the members of these three different classes - - - p. 193

- Chap. 7. Fourth consists of Dr. Peckard—then of the Author—Author wishes to embark in the cause—falls in with several of the members of these classes - p. 203

- Chap. 8. Fourth class continued—Langton—Baker—and others—Author now embarks in the cause as a business of his life - - - - p. 218

- Chap. 9. Fourth class continued—Sheldon—Mackworth—and others—Author seeks for further information on the subject—and visits Members of Parliament - p. 231 [589]

- Chap. 10. Fourth class continued—Author enlarges his knowledge—Meeting at Mr. Wilberforce’s—Remarkable junction of all the four classes, and a Committee formed out of them, in May 1787, for the Abolition of the Slave-trade - - - - - p. 243

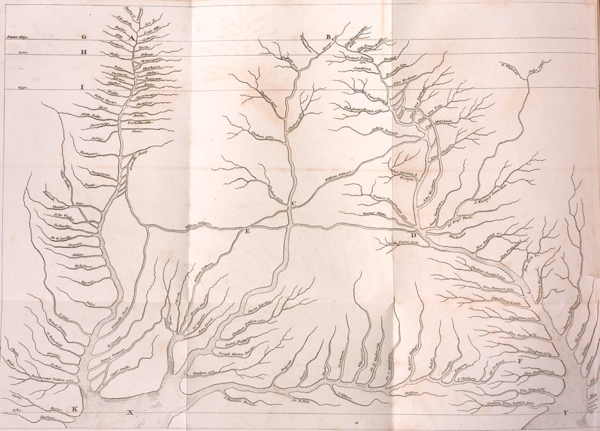

- Chap. 11. History of the preceding classes, and of their junction, shown by means of a map - p. 259

- Chap. 12. Author endeavours to do away the charge of ostentation in consequence of becoming so conspicuous in this work - - - - - p. 267

- Chap. 13. Proceedings of the Committee—Emancipation declared to be no part of its object—Wrongs of Africa by Mr. Roscoe - - - - p. 276

- Chap. 14. Author visits Bristol to collect information—Ill usage of seamen in the Slave-trade—Articles of African produce—Massacre at Calebar - - p. 292

- Chap. 15. Mode of procuring and paying seamen in that trade—their mortality in it—Construction and admeasurement of Slave-ships—Difficulty of procuring evidence—Cases of Gardiner and Arnold - - p. 320

- Chap. 16. Author meets with Alexander Falconbridge—visits ill-treated and disabled seamen—takes a mate out of one of the Slave-vessels—and puts another in prison for murder - - - - p. 345

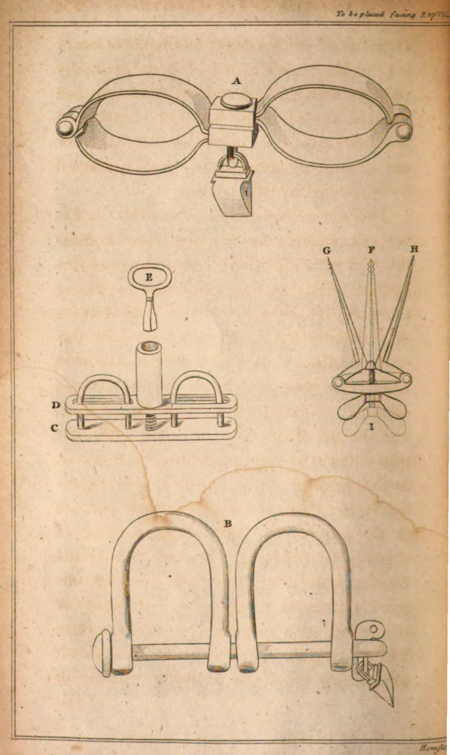

- Chap. 17. Visits Liverpool—Specimens of African produce—Dock-duties—Iron-instruments used in the traffic—His introduction to Mr. Norris - - p. 368

- Chap. 18. Manner of procuring and paying seamen at Liverpool in the Slave-trade—their treatment and mortality—Murder of Peter Green—Dangerous situation of the Author in consequence of his inquiries - - p. 391

- Chap. 19. Author proceeds to Manchester—delivers a discourse there on the subject of the Slave-trade—revisits [590] Bristol—New and difficult situation there—suddenly crosses the Severn at night—returns to London p. 415

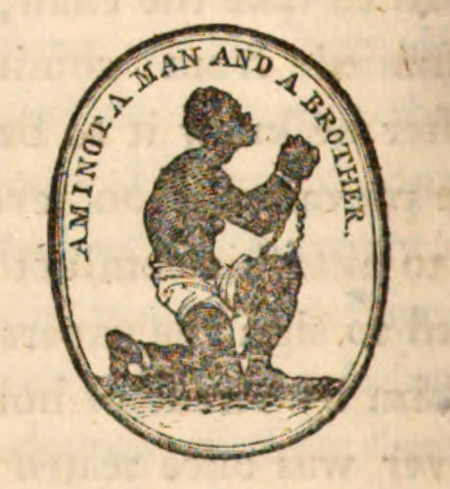

- Chap. 20. Labours of the Committee during the Author’s journey—Mr. Sharp elected chairman—Seal engraved—Letters from different correspondents to the Committee p. 441

- Chap. 21. Further labours of the Committee to February 1788—List of new Correspondents - - p. 458

- Chap. 22. Progress of the cause to the middle of May—Petitions to Parliament—Author’s interviews with Mr. Pitt and Mr. Grenville—Privy council inquire into the subject—examine Liverpool-delegates—Proceedings of the Committee for the abolition—Motion and debate in the House of Commons—Discussion of the general question postponed to the next session - - p. 469

- Chap. 23. Progress to the middle of July—Bill to diminish the horrors of the Middle Passage—Evidence examined against it—Debates—Bill passed through both Houses—Proceedings of the Committee, and effects of them. p. 527

Table of Contents for Vol. 2

VOL. II.

- Chap. 1. Continuation from June 1788 to July 1789—Author travels in search of fresh evidence—Privy council resume their examinations—prepare their report—Proceedings of the Committee for the abolition—and of the Planters and others—Privy council report laid on the table of the House of Commons—Debate upon it—Twelve propositions—Opponents refuse to argue from the report—Examine new evidence of their own in the House of Commons—Renewal of the Middle Passage-Bill—Death and character of Ramsay - p. 1 [591]

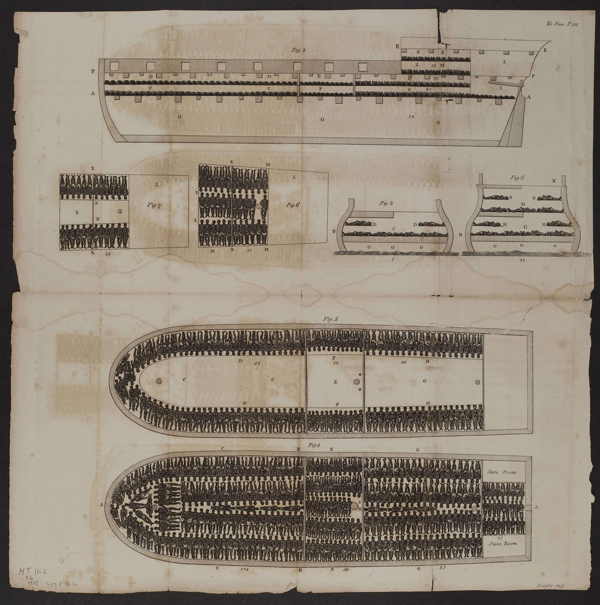

- Chap. 2. Continuation from July 1789 to July 1790—Author travels to Paris to promote the abolition in France—His proceedings there—returns to England—Examination of opponents’ evidence resumed in the Commons—Author travels in quest of new evidence on the side of the abolition—This, after great opposition, introduced—Renewal of the Middle Passage-Bill—Section of the Slave-ship—Cowper’s Negro’s Complaint—Wedgwood’s Cameos. p. 118

- Chap. 3. Continuation from July 1790 to July 1791—Author travels again—Examinations on the side of the abolition resumed in the Commons—List of those examined—Cruel circumstances of the times—Motion for the abolition of the trade—Debates—Motion lost—Resolutions of the Committee—Sierra Leone Company established p. 194

- Chap. 4. Continuation from July 1791 to July 1792—Author travels again—People begin to leave off sugar—Petition Parliament—Motion renewed in the Commons—Debates—Abolition resolved upon, but not to commence till 1796—The Lords determine upon hearing evidence on the resolution—This evidence introduced—Further hearing of it postponed to the next session - p. 346

- Chap. 5. Continuation from July 1792 to July 1793—Author travels again—Motion to renew the Resolution of the last year in the Commons—Motion lost—New motion to abolish the foreign Slave-trade—Motion lost—Proceedings of the Lords - - - p. 461

- Chap. 6. Continuation from July 1793 to July 1794—Author travels again—Motion to abolish the foreign Slave-trade renewed and carried—but lost in the Lords—Further proceedings there—Author, on account of declining health, obliged to retire from the cause - - p. 465

- Chap. 7. Continuation from July 1794 to July 1799—Various motions within this period - - p. 472 [592]

- Chap. 8. Continuation from July 1799 to July 1805—Various motions within this period - - p. 489

- Chap. 9. Continuation from July 1805 to July 1806—Author, restored, joins the Committee again—Death of Mr. Pitt—Foreign Slave-trade abolished—Resolution to take measures for the total abolition of the trade—Address to the King to negotiate with foreign powers for their concurrence in it—Motion to prevent new vessels going into the trade—all these carried through both Houses of Parliament - - - - p. 501

- Chap. 10. Continuation from July 1806 to July 1807—Death of Mr. Fox—Bill for the total abolition carried in the Lords—Sent from thence to the Commons—amended, and passed there, and sent back to the Lords—receives the royal assent—Reflections on this great event p. 564

THE HISTORY OF THE RISE, PROGRESS, AND ACCOMPLISHMENT OF THE ABOLITION OF THE SLAVE TRADE. VOLUME I.

[ii]

to

The Right Honourable WILLIAM, LORD GRENVILLE,

The Right Honourable CHARLES, EARL GREY,

(late Viscount Howick),

The Right Honourable FRANCIS, EARL MOIRA,

The Right Honourable GEORGE JOHN, EARL SPENCER,

The Right Honourable HENRY RICHARD, LORD HOLLAND,

The Right Honourable THOMAS, LORD ERSKINE,

The Right Honourable EDWARD, LORD ELLENBOROUGH,

The Right Honourable LORD HENRY PETTY,

The Right Honourable THOMAS GRENVILLE,

nine out of twelve of his majesty’s late cabinet ministers,

to whose wise and virtuous administration belongs

the unparalleled and eternal glory

of the annihilation

(as par as their power extended)

of one of the greatest sources of crimes and sufferings,

ever recorded in the annals of mankind;

and to the memories

of

The Right Honourable WILLIAM PITT,

and of

The Right Honourable CHARLES JAMES FOX,

under whose fostering influence

the great work was begun and promoted,

THIS HISTORY of the RISE, PROGRESS, and ACCOMPLISHMENT

of the ABOLITION of the SLAVE-TRADE

is respectfully and gratefully inscribed.

[I-1]

CHAPTER I.↩

No subject more pleasing than that of the removal of evils—Evils have existed almost from the beginning of the world—but there is a power in our nature to counteract them—this power increased by Christianity—of the evils removed by Christianity one of the greatest is the Slave-trade—The joy we ought to feel on its abolition from a contemplation of the nature of it—and of the extent of it—and of the difficulty of subduing it—Usefulness also of the contemplation of this subject.

I scarcely know of any subject, the contemplation of which is more pleasing than that of the correction or of the removal of any of the acknowledged evils of life; for while we rejoice to think that the sufferings [I-2] of our fellow-creatures have been thus, in any instance, relieved, we must rejoice equally to think that our own moral condition must have been necessarily improved by the change.

That evils, both physical and moral, have existed long upon earth there can be no doubt. One of the sacred writers, to whom we more immediately appeal for the early history of mankind, informs us that the state of our first parents was a state of innocence and happiness; but that, soon after their creation, sin and misery entered into the world. The Poets in their fables, most of which, however extravagant they may seem, had their origin in truth, speak the same language. Some of these represent the first condition of man by the figure of the golden, and his subsequent degeneracy and subjection to suffering by that of the silver, and afterwards of the iron, age. Others tell us that the first female was made of clay; that she was called Pandora, because every necessary gift, qualification, or endowment, was given to her by the Gods, but that she received from Jupiter at the same time, a box, from which, when opened, a multitude of [I-3] disorders sprung, and that these spread themselves immediately afterwards among all of the human race. Thus it appears, whatever authorities we consult, that those which may be termed the evils of life existed in the earliest times. And what does subsequent history, combined with our own experience, tell us, but that these have been continued, or that they have come down, in different degrees, through successive generations of men, in all the known countries of the universe, to the present day?

But though the inequality visible in the different conditions of life, and the passions interwoven into our nature, (both which have been allotted to us for wise purposes, and without which we could not easily afford a proof of the existence of that which is denominated virtue,) have a tendency to produce vice and wretchedness among us, yet we see in this our constitution what may operate partially as preventives and correctives of them. If there be a radical propensity in our nature to do that which is wrong, there is on the other hand a counteracting power within it, or an impulse, by means of the action of the Divine Spirit [I-4] upon our minds, which urges us to do that which is right. If the voice of temptation, clothed in musical and seducing accents, charms us one way, the voice of holiness, speaking to us from within in a solemn and powerful manner, commands us another. Does one man obtain a victory over his corrupt affections? an immediate perception of pleasure, like the feeling of a reward divinely conferred upon him, is noticed.—Does another fall prostrate beneath their power? a painful feeling, and such as pronounces to him the sentence of reproof and punishment, is found to follow.—If one, by suffering his heart to become hardened, oppresses a fellow-creature, the tear of sympathy starts up in the eye of another, and the latter instantly feels a desire, involuntarily generated, of flying to his relief. Thus impulses, feelings, and dispositions have been implanted in our nature for the purpose of preventing and rectifying the evils of life. And as these have operated so as to stimulate some men to lessen them by the exercise of an amiable charity, so they have operated to stimulate others, in various other ways, to the same end. Hence the philosopher [I-5] has left moral precepts behind him in favour of benevolence, and the legislator has endeavoured to prevent barbarous practices by the introduction of laws.

In consequence then of these impulses and feelings, by which the pure power in our nature is thus made to act as a check upon the evil part of it, and in consequence of the influence which philosophy and legislative wisdom have had in their respective provinces, there has been always, in all times and countries, a counteracting energy, which has opposed itself more or less to the crimes and miseries of mankind. But it seems to have been reserved for Christianity to encrease this energy, and to give it the widest possible domain. It was reserved for her, under the same Divine Influence, to give the best views of the nature, and of the present and future condition of man; to afford the best moral precepts, to communicate the most benign stimulus to the heart, to produce the most blameless conduct, and thus to cut off many of the causes of wretchedness, and to heal it wherever it was found. At her command, wherever she has been duly acknowledged, many of the evils of [I-6] life have already fled. The prisoner of war is no longer led into the amphitheatre to become a gladiator, and to imbrue his hands in the blood of his fellow-captive for the sport of a thoughtless multitude. The stern priest, cruel through fanaticism and custom, no longer leads his fellow-creature to the altar, to sacrifice him to fictitious Gods. The venerable martyr, courageous through faith and the sanctity of his life, is no longer hurried to the flames. The haggard witch, poring over her incantations by moon-light, no longer scatters her superstitious poison among her miserable neighbours, nor suffers for her crime.

But in whatever way Christianity may have operated towards the increase of this energy, or towards a diminution of human misery, it has operated in none more powerfully than by the new views, and consequent duties, which it introduced on the subject of charity, or practical benevolence and love. Men in ancient times looked upon their talents, of whatever description, as their own, which they might use or cease to use at their discretion. But the author of our religion was the first who taught that, [I-7] however in a legal point of view the talent of individuals might belong exclusively to themselves, so that no other person had a right to demand the use of it by force, yet in the Christian dispensation they were but the stewards of it for good; that so much was expected from this stewardship, that it was difficult for those who were entrusted with it to enter into his spiritual kingdom; that these had no right to conceal their talent in a napkin; but that they were bound to dispense a portion of it to the relief of their fellow-creatures; and that in proportion to the magnitude of it they were accountable for the extensiveness of its use. He was the first, who pronounced the misapplication of it to be a crime, and to be a crime of no ordinary dimensions. He was the first, who broke down the boundary between Jew and Gentile, and therefore the first, who pointed out to men the inhabitants of other countries for the exercise of their philanthropy and love. Hence a distinction is to be made both in the principle and practice of charity, as existing in ancient or in modern times. Though the old philosophers, historians, and poets, frequently [I-8] inculcated benevolence, we have no reason to conclude from any facts they have left us, that persons in their days did any thing more than occasionally relieve an unfortunate object, who might present himself before them, or that, however they might deplore the existence of public evils among them, they joined in associations for their suppression, or that they carried their charity, as bodies of men, into other kingdoms. To Christianity alone we are indebted for the new and sublime spectacle of seeing men going beyond the bounds of individual usefulness to each other—of seeing them associate for the extirpation of private and public misery—and of seeing them carry their charity, as a united brotherhood, into distant lands. And in this wider field of benevolence it would be unjust not to confess, that no country has shone with more true lustre than our own, there being scarcely any case of acknowledged affliction, for which some of her Christian children have not united in an attempt to provide relief.

Among the evils, corrected or subdued, either by the general influence of Christianity [I-9] on the minds of men, or by particular associations of Christians, the African [2] Slave-trade appears to me to have occupied the foremost place. The abolition of it, therefore, of which it has devolved upon me to write the history, should be accounted as one of the greatest blessings, and, as such, should be one of the most copious sources of our joy. Indeed I know of no evil, the removal of which should excite in us a higher degree of pleasure. For in considerations of this kind, are we not usually influenced by circumstances? Are not our feelings usually affected according to the situation, or the magnitude, or the importance of these? Are they not more or less elevated as the evil under our contemplation has been more or less productive of misery, or more or less productive of guilt? Are they not more or less elevated, again, as we have found it more or less considerable in extent? Our sensations will undoubtedly be in proportion to such circumstances, or our [I-10] joy to the appretiation or mensuration of the evil which has been removed.

To value the blessing of the abolition as we ought, or to appretiate the joy and gratitude which we ought to feel concerning it, we must enter a little into the circumstances of the trade. Our statement, however, of these needs not be long. A few pages will do all that is necessary! A glance only into such a subject as this will be sufficient to affect the heart—to arouse our indignation and our pity,—and to teach us the importance of the victory obtained.

The first subject for consideration, towards enabling us to make the estimate in question, will be that of the nature of the evil belonging to the Slave-trade. This may be seen by examining it in three points of view:—First, As it has been proved to arise on the continent of Africa in the course of reducing the inhabitants of it to slavery;—Secondly, In the course of conveying them from thence to the lands or colonies of other nations;—And Thirdly, In continuing them there as slaves.

To see it as it has been shown to arise in [I-11] the first case, let us suppose ourselves on the Continent just mentioned. Well then—We are landed—We are already upon our travels—We have just passed through one forest—We are now come to a more open place, which indicates an approach to habitation. And what object is that, which first obtrudes itself upon our sight? Who is that wretched woman, whom we discover under that noble tree, wringing her hands, and beating her breast, as if in the agonies of despair? Three days has she been there at intervals to look and to watch, and this is the fourth morning, and no tidings of her children yet. Beneath its spreading boughs they were accustomed to play—But alas! the savage man-stealer interrupted their playful mirth, and has taken them for ever from her sight.

But let us leave the cries of this unfortunate woman, and hasten into another district:—And what do we first see here? Who is he, that just now started across the narrow pathway, as if afraid of a human face? What is that sudden rustling among the leaves? Why are those persons flying from our approach, and hiding themselves in yon [I-12] darkest thicket? Behold, as we get into the plain, a deserted village! The rice-field has been just trodden down around it. An aged man, venerable by his silver beard, lies wounded and dying near the threshold of his hut. War, suddenly instigated by avarice, has just visited the dwellings which we see. The old have been butchered, because unfit for slavery, and the young have been carried off, except such as have fallen in the conflict, or have escaped among the woods behind us.

But let us hasten from this cruel scene, which gives rise to so many melancholy reflections. Let us cross yon distant river, and enter into some new domain. But are we relieved even here from afflicting spectacles? Look at that immense crowd, which appears to be gathered in a ring. See the accused innocent in the middle. The ordeal of poisonous water has been administered to him, as a test of his innocence or his guilt. He begins to be sick, and pale. Alas! yon mournful shriek of his relatives confirms that the loss of his freedom is now sealed.

And whither shall we go now? The night is approaching fast. Let us find some [I-13] friendly hut, where sleep may make us forget for a while the sorrows of the day. Behold a hospitable native ready to receive us at his door! Let us avail ourselves of his kindness. And now let us give ourselves to repose. But why, when our eyelids are but just closed, do we find ourselves thus suddenly awakened? What is the meaning of the noise around us, of the trampling of people’s feet, of the rustling of the bow, the quiver, and the lance? Let us rise up and inquire. Behold! the inhabitants are all alarmed! A wakeful woman has shown them yon distant column of smoke and blaze. The neighbouring village is on fire. The prince, unfaithful to the sacred duty of the protection of his subjects, has surrounded them. He is now burning their habitations, and seizing, as saleable booty, the fugitives from the flames.

Such then are some of the scenes that have been passing in Africa in consequence of the existence of the Slave-trade; or such is the nature of the evil, as it has shown itself in the first of the cases we have noticed. Let us now estimate it as it has been proved to exist in the second; or let us examine the [I-14] state of the unhappy Africans, reduced to slavery in this manner, while on board the vessels, which are to convey them across the ocean to other lands. And here I must observe at once, that, as far as this part of the evil is concerned, I am at a loss to describe it. Where shall I find words to express properly their sorrow, as arising from the reflection of being parted for ever from their friends, their relatives, and their country? Where shall I find language to paint in appropriate colours the horror of mind brought on by thoughts of their future unknown destination, of which they can augur nothing but misery from all that they have yet seen? How shall I make known their situation, while labouring under painful disease, or while struggling in the suffocating holds of their prisons, like animals inclosed in an exhausted receiver? How shall I describe their feelings as exposed to all the personal indignities, which lawless appetite or brutal passion may suggest? How shall I exhibit their sufferings as determining to refuse sustenance and die, or as resolving to break their chains, and, disdaining to live as slaves, to punish their oppressors? How shall I give [I-15] an idea of their agony, when under various punishments and tortures for their reputed crimes? Indeed every part of this subject defies my powers, and I must therefore satisfy myself and the reader with a general representation, or in the words of a celebrated member of Parliament, that “Never was so much human suffering condensed in so small a space.”

I come now to the evil, as it has been proved to arise in the third case; or to consider the situation of the unhappy victims of the trade, when their painful voyages are over, or after they have been landed upon their destined shores. And here we are to view them first under the degrading light of cattle. We are to see them examined, handled, selected, separated, and sold. Alas! relatives are separated from relatives, as if, like cattle, they had no rational intellect, no power of feeling the nearness of relationship, nor sense of the duties belonging to the ties of life! We are next to see them labouring, and this for the benefit of those, to whom they are under no obligation, by any law either natural or divine, to obey. We are to see them, if refusing the commands [I-16] of their purchasers, however weary, of feeble, or indisposed, subject to corporal punishments, and, if forcibly resisting them, to death. We are to see them in a state of general degradation and misery. The knowledge, which their oppressors have of their own crime in having violated the rights of nature, and of the disposition of the injured to seek all opportunities of revenge, produces a fear, which dictates to them the necessity of a system of treatment by which they shall keep up a wide distinction between the two, and by which the noble feelings of the latter shall be kept down, and their spirits broken. We are to see them again subject to individual persecution, as anger, or malice, or any bad passion may suggest. Hence the whip—the chain—the iron-collar. Hence the various modes of private torture, of which so many accounts have been truly given. Nor can such horrible cruelties be discovered so as to be made punishable, while the testimony of any number of the oppressed is invalid against the oppressors, however they may be offences against the laws. And, lastly, we are to see their innocent offspring, against whose personal liberty [I-17] the shadow of an argument cannot be advanced, inheriting all the miseries of their parents’ lot.

The evil then, as far as it has been hitherto viewed, presents to us in its three several departments a measure of human suffering not to be equalled—not to be calculated—not to be described. But would that we could consider this part of the subject as dismissed! Would that in each of the departments now examined there was no counterpart left us to contemplate! But this cannot be. For if there be persons, who suffer unjustly, there must be others, who oppress. And if there be those who oppress, there must be to the suffering, which has been occasioned, a corresponding portion of immorality or guilt.

We are obliged then to view the counterpart of the evil in question, before we can make a proper estimate of the nature of it. And, in examining this part of it, we shall find that we have a no less frightful picture to behold than in the former cases; or that, while the miseries endured by the unfortunate Africans excite our pity on the one [I-18] hand, the vices, which are connected with them, provoke our indignation and abhorrence on the other. The Slave-trade, in this point of view, must strike us as an immense mass of evil on account of the criminality attached to it, as displayed in the various branches of it, which have already been examined. For, to take the counterpart of the evil in the first of these, can we say, that no moral turpitude is to be placed to the account of those, who living on the continent of Africa give birth to the enormities, which take place in consequence of the prosecution of this trade? Is not that man made morally worse, who is induced to become a tiger to his species, or who, instigated by avarice, lies in wait in the thicket to get possession of his fellow-man? Is no injustice manifest in the land, where the prince, unfaithful to his duty, seizes his innocent subjects, and sells them for slaves? Are no moral evils produced among those communities, which make war upon other communities for the sake of plunder, and without any previous provocation or offence? Does no crime attach to those, who accuse others falsely, or who multiply and divide crimes for [I-19] the sake of the profit of the punishment, and who for the same reason, continue the use of barbarous and absurd ordeals as a test of innocence or guilt?

In the second of these branches the counterpart of the evil is to be seen in the conduct of those, who purchase the miserable natives in their own country, and convey them to distant lands. And here questions, similar to the former, may be asked. Do they experience no corruption of their nature, or become chargeable with no violation of right, who, when they go with their ships to this continent, know the enormities which their visits there will occasion, who buy their fellow-creature man, and this, knowing the way in which he comes into their hands, and who chain, and imprison, and scourge him? Do the moral feelings of those persons escape without injury, whose hearts are hardened? And can the hearts of those be otherwise than hardened, who are familiar with the tears and groans of innocent strangers forcibly torn away from every thing that is dear to them in life, who are accustomed to see them on board their vessels in a state of suffocation and in the agonies [I-20] of despair, and who are themselves in the habits of the cruel use of arbitrary power?

The counterpart of the evil in its third branch is to be seen in the conduct of those, who, when these miserable people have been landed, purchase and carry them to their respective homes. And let us see whether a mass of wickedness is not generated also in the present case. Can those have nothing to answer for, who separate the faithful ties which nature and religion have created? Can their feelings be otherwise than corrupted, who consider their fellow-creatures as brutes, or treat those as cattle, who may become the temples of the Holy Spirit, and in whom the Divinity disdains not himself to dwell? Is there no injustice in forcing men to labour without wages? Is there no breach of duty, when we are commanded to clothe the naked, and feed the hungry, and visit the sick and in prison, in exposing them to want, in torturing them by cruel punishment, and in grinding them down by hard labour, so as to shorten their days? Is there no crime in adopting a system, which keeps down all the noble faculties of [I-21] their souls, and which positively debases and corrupts their nature? Is there no crime in perpetuating these evils among their innocent offspring? And finally, besides all these crimes, is there not naturally in the familiar sight of the exercise, but more especially in the exercise itself, of uncontrolled power, that which vitiates the internal man? In seeing misery stalk daily over the land, do not all become insensibly hardened? By giving birth to that misery themselves, do they not become abandoned? In what state of society are the corrupt appetites so easily, so quickly, and so frequently indulged, and where else, by means of frequent indulgence, do these experience such a monstrous growth? Where else is the temper subject to such frequent irritation, or passion to such little control? Yes—If the unhappy slave is in an unfortunate situation, so is the tyrant who holds him. Action and reaction are equal to each other, as well in the moral as in the natural world. You cannot exercise an improper dominion over a fellow-creature, but by a wise ordering of Providence you must necessarily injure yourself.

Having now considered the nature of the [I-22] evil of the Slave-trade in its three separate departments of suffering, and in its corresponding counterparts of guilt, I shall make a few observations on the extent of it.

On this subject it must strike us, that the misery and the crimes included in the evil, as it has been found in Africa, were not like common maladies, which make a short or periodical visit and then are gone, but that they were continued daily. Nor were they like diseases, which from local causes attack a village or a town, and by the skill of the physician, under the blessing of Providence, are removed, but they affected a whole continent. The trade with all its horrors began at the river Senegal, and continued, winding with the coast, through its several geographical divisions to Cape Negro; a distance of more than three thousand miles. In various lines or paths formed at right angles from the shore, and passing into the heart of the country, slaves were procured and brought down. The distance, which many of them travelled, was immense. Those, who have been in Africa, have assured us, that they came as far as from the sources of their largest rivers, [I-23] which we know to be many hundred miles in-land, and the natives have told us, in their way of computation, that they came a journey of many moons.

It must strike us again, that the misery and the crimes, included in the evil, as it has been shown in the transportation, had no ordinary bounds. They were not to be seen in the crossing of a river, but of an ocean. They did not begin in the morning and end at night, but were continued for many weeks, and sometimes by casualties for a quarter of the year. They were not limited to the precincts of a solitary ship, but were spread among many vessels; and these were so constantly passing, that the ocean itself never ceased to be a witness of their existence.

And it must strike us finally, that the misery and crimes, included in the evil as it has been found in foreign lands, were not confined within the shores of a little island. Most of the islands of a continent, and many of these of considerable population and extent, were filled with them. And the continent itself, to which these geographically belong, was widely polluted by their [I-24] domain. Hence, if we were to take the vast extent of space occupied by these crimes and sufferings from the heart of Africa to its shores, and that which they filled on the continent of America and the islands adjacent, and were to join the crimes and sufferings in one to those in the other by the crimes and sufferings which took place in the track of the vessels successively crossing the Atlantic, we should behold a vast belt as it were of physical and moral evil, reaching through land and ocean to the length of nearly half the circle of the globe.

The next view, which I shall take of this evil, will be as it relates to the difficulty of subduing it.

This difficulty may be supposed to have been more than ordinarily great. Many evils of a public nature, which existed in former times, were the offspring of ignorance and superstition, and they were subdued of course by the progress of light and knowledge. But the evil in question began in avarice. It was nursed also by worldly interest. It did not therefore so easily yield to the usual correctives of disorders [I-25] in the world. We may observe also, that the interest by which it was thus supported, was not that of a few individuals, nor of one body, but of many bodies of men. It was interwoven again into the system of the commerce and of the revenue of nations. Hence the merchant—the planter—the mortgagee—the manufacturer—the politician—the legislator—the cabinet-minister—lifted up their voices against the annihilation of it. For these reasons the Slave-trade may be considered, like the fabulous hydra, to have had a hundred heads, every one of which it was necessary to cut off before it could be subdued. And as none but Hercules was fitted to conquer the one, so nothing less than extraordinary prudence, courage, labour, and patience, could overcome the other. To protection in this manner by his hundred interests it was owing, that the monster stalked in security for so long a time. He stalked too in the open day, committing his mighty depredations. And when good men, whose duty it was to mark him as the object of their destruction, began to assail him, he did not fly, but [I-26] gnashed his teeth at them, growling savagely at the same time, and putting himself into a posture of defiance.

We see then, in whatever light we consider the Slave-trade, whether we examine into the nature of it, or whether we look into the extent of it, or whether we estimate the difficulty of subduing it, we must conclude that no evil more monstrous has ever existed upon earth. But if so, then we have proved the truth of the position, that the abolition of it ought to be accounted by us as one of the greatest blessings, and that it ought to be one of the most copious sources of our joy. Indeed I do not know, how we can sufficiently express what we ought to feel upon this occasion. It becomes us as individuals to rejoice. It becomes us as a nation to rejoice. It becomes us even to perpetuate our joy to our posterity. I do not mean however by anniversaries, which are to be celebrated by the ringing of bells and convivial meetings, but by handing down this great event so impressively to our children, as to raise in them, if not continual, yet frequently renewed thanksgivings, [I-27] to the great Creator of the universe, for the manifestation of this his favour, in having disposed our legislators to take away such a portion of suffering from our fellow-creatures, and such a load of guilt from our native land.

And as the contemplation of the removal of this monstrous evil should excite in us the most pleasing and grateful sensations, so the perusal of the history of it should afford us lessons, which it must be useful to us to know or to be reminded of. For it cannot be otherwise than useful to us to know the means which have been used, and the different persons who have moved, in so great a cause. It cannot be otherwise than useful to us to be impressively reminded of the simple axiom, which the perusal of this history will particularly suggest to us, that “the greatest works must have a beginning;” because the fostering of such an idea in our minds cannot but encourage us to undertake the removal of evils, however vast they may appear in their size, or however difficult to overcome. It cannot again be otherwise than useful to us to be assured [I-28] (and this history will assure us of it) that in any work, which is a work of righteousness, however small the beginning may be, or however small the progress may be that we may make in it, we ought never to despair; for that, whatever checks and discouragements we may meet with, “no virtuous effort is ever ultimately lost.” And finally, it cannot be otherwise than useful to us to form the opinion, which the contemplation of this subject must always produce, namely, that many of the evils, which are still left among us, may, by an union of wise and virtuous individuals, be greatly alleviated, if not entirely done away: for if the great evil of the Slave-trade, so deeply entrenched by its hundred interests, has fallen prostrate before the efforts of those who attacked it, what evil of a less magnitude shall not be more easily subdued? O may reflections of this sort always enliven us, always encourage us, always stimulate us to our duty! May we never cease to believe, that many of the miseries of life are still to be remedied, or to rejoice that we may be permitted, if we will only make [I-29] ourselves worthy by our endeavours, to heal them! May we encourage for this purpose every generous sympathy that arises in our hearts, as the offspring of the Divine influence for our good, convinced that we are not born for ourselves alone, and that the Divinity never so fully dwells in us, as when we do his will; and that we never do his will more agreeably, as far as it has been revealed to us, than when we employ our time in works of charity towards the rest of our fellow-creatures!

[I-30]

CHAPTER II.↩

As it is desirable to know the true sources of events in history, so this will be realized in that of the abolition of the Slave-trade—Inquiry as to those who favoured the cause of the Africans previously to the year 1787—All these to be considered as necessary forerunners in that cause—First forerunners were Cardinal Ximenes—the Emperor Charles the Fifth—Pope Leo the Tenth—Elizabeth queen of England—Louis the Thirteenth of France.

It would be considered by many, who have stood at the mouth of a river, and witnessed its torrent there, to be both an interesting and a pleasing journey to go to the fountain-head, and then to travel on its banks downwards, and to mark the different streams in each side, which should run into it and feed it. So I presume the reader will not be a little interested and entertained in viewing with me the course of the abolition of the Slave-trade, in first finding its source, and then in tracing the different springs which have contributed to its increase. And here I may observe that, in doing this, [I-31] we shall have advantages, which historians have not always had in developing the causes of things. Many have handed down to us events, for the production of which they have given us but their own conjectures. There has been often indeed such a distance between the events themselves and the lives of those who have recorded them, that the different means and motives belonging to them have been lost through time. On the present occasion, however, we shall have the peculiar satisfaction of knowing that we communicate the truth, or that those, which we unfold, are the true causes and means. For the most remote of all the human springs, which can be traced as having any bearing upon the great event in question, will fall within the period of three centuries, and the most powerful of them within the last twenty years. These circumstances indeed have had their share in inducing me to engage in the present history. Had I measured it by the importance of the subject, I had been deterred: but believing that most readers love the truth, and that it ought to be the object of all writers to promote it, and believing [I-32] moreover, that I was in possession of more facts on this subject than any other person, I thought I was peculiarly called upon to undertake it.

In tracing the different streams from whence the torrent arose, which has now happily swept away the Slave-trade, I must begin with an inquiry as to those who favoured the cause of the injured Africans from the year 1516 to the year 1787, at which latter period a number of persons associated themselves in England for its abolition. For though they, who belonged to this association, may, in consequence of having pursued a regular system, be called the principal actors, yet it must be acknowledged that their efforts would never have been so effectual, if the minds of men had not been prepared by others, who had moved before them. Great events have never taken place without previously disposing causes. So it is in the case before us. Hence they, who lived even in early times, and favoured this great cause, may be said to have been necessary precursors in it. And here it may be proper to observe, that it is by no means necessary that all these [I-33] should have been themselves actors in the production of this great event. Persons have contributed towards it in different ways:—Some have written expressly on the subject, who have had no opportunity of promoting it by personal exertions. Others have only mentioned it incidentally in their writings. Others, in an elevated rank and station, have cried out publicly concerning it, whose sayings have been recorded. All these, however, may be considered as necessary forerunners in their day. For all of them have brought the subject more or less into notice. They have more or less enlightened the mind upon it. They have more or less impressed it. And therefore each may be said to have had his share in diffusing and keeping up a certain portion of knowledge and feeling concerning it, which has been eminently useful in the promotion of the cause.

It is rather remarkable, that the first forerunners and coadjutors should have been men in power.

So early as in the year 1503 a few slaves had been sent from the Portuguese settlements [I-34] in Africa into the Spanish colonies in America. In 1511, Ferdinand the Fifth, king of Spain, permitted them to be carried in greater numbers. Ferdinand, however, must have been ignorant in these early times of the piratical manner in which the Portuguese had procured them. He could have known nothing of their treatment when in bondage, nor could he have viewed the few uncertain adventurous transportations of them into his dominions in the western world, in the light of a regular trade. After his death, however, a proposal was made by Bartholomew de las Casas, the bishop of Chiapa, to Cardinal Ximenes, who held the reins of the government of Spain till Charles the Fifth came to the throne, for the establishment of a regular system of commerce in the persons of the native Africans. The object of Bartholomew de las Casas was undoubtedly to save the American Indians, whose cruel treatment and almost extirpation he had witnessed during his residence among them, and in whose behalf he had undertaken a voyage to the court of Spain. It is difficult to reconcile this proposal with the [I-35] humane and charitable spirit of the bishop of Chiapa. But it is probable he believed that a code of laws would soon be established in favour both of Africans and of the natives in the Spanish settlements, and that he flattered himself that, being about to return and to live in the country of their slavery, he could look to the execution of it. The cardinal, however, with a foresight, a benevolence, and a justice, which will always do honour to his memory, refused the proposal, not only judging it to be unlawful to consign innocent people to slavery at all, but to be very inconsistent to deliver the inhabitants of one country from a state of misery by consigning to it those of another. Ximenes therefore may be considered as one of the first great friends of the Africans after the partial beginning of the trade.

This answer of the cardinal, as it showed his virtue as an individual, so it was peculiarly honourable to him as a public man, and ought to operate as a lesson to other statesmen, how they admit any thing new among political regulations and establishments, which is connected in the smallest degree with injustice. For evil, when once [I-36] sanctioned by governments, spreads in a tenfold degree, and may, unless seasonably checked, become so ramified, as to affect the reputation of a country, and to render its own removal scarcely possible without detriment to the political concerns of the state. In no instance has this been verified more than in the case of the Slave-trade. Never was our national character more tarnished, and our prosperity more clouded by guilt. Never was there a monster more difficult to subdue. Even they, who heard as it were the shrieks of oppression, and wished to assist the sufferers, were fearful of joining in their behalf. While they acknowledged the necessity of removing one evil, they were terrified by the prospect of introducing another; and were therefore only able to relieve their feelings, by lamenting in the bitterness of their hearts, that this traffic had ever been begun at all.

After the death of cardinal Ximenes, the emperor Charles the Fifth, who had come into power, encouraged the Slave-trade. In 1517 he granted a patent to one of his Flemish favourites, containing an exclusive right of importing four thousand Africans [I-37] into America. But he lived long enough to repent of what he had thus inconsiderately done. For in the year 1542 he made a code of laws for the better protection of the unfortunate Indians in his foreign dominions; and he stopped the progress of African slavery by an order, that all slaves in his American islands should be made free. This order was executed by Pedro de la Gasca. Manumission took place as well in Hispaniola as on the Continent. But on the return of Gasca to Spain, and the retirement of Charles into a monastery, slavery was revived.

It is impossible to pass over this instance of the abolition of slavery by Charles in all his foreign dominions, without some comments. It shows him, first, to have been a friend both to the Indians and the Africans, as a part of the human race. It shows he was ignorant of what he was doing when he gave his sanction to this cruel trade. It shows when legislators give one set of men an undue power over another, how quickly they abuse it,—or he never would have found himself obliged in the short space of twenty-five years to undo that which he had countenanced as a great state-measure. [I-38] And while it confirms the former lesson to statesmen, of watching the beginnings or principles of things in their political movements, it should teach them never to persist in the support of evils, through the false shame of being obliged to confess that they had once given them their sanction, nor to delay the cure of them because, politically speaking, neither this nor that is the proper season; but to do them away instantly, as there can only be one fit or proper time in the eye of religion, namely, on the conviction of their existence.

From the opinions of cardinal Ximenes and of the emperor Charles the Fifth, I hasten to that which was expressed much about the same time, in a public capacity, by pope Leo the Tenth. The Dominicans in Spanish America, witnessing the cruel treatment which the slaves underwent there, considered slavery as utterly repugnant to the principles of the gospel, and recommended the abolition of it. The Franciscans did not favour the former in this their scheme of benevolence; and the consequence was, that a controversy on this subject sprung up between them, which was carried to this [I-39] pope for his decision. Leo exerted himself, much to his honour, in behalf of the poor sufferers, and declared “That not only the christian religion, but that Nature herself cried out against a state of slavery.” This answer was certainly worthy of one, who was deemed the head of the christian church. It must, however, be confessed that it would have been strange if Leo, in his situation as pontiff, had made a different reply. He could never have denied that God was no respecter of persons. He must have acknowledged that men were bound to love each other as brethren. And, if he admitted the doctrine, that all men were accountable for their actions hereafter, he could never have prevented the deduction, that it was necessary they should be free. Nor could he, as a man of high attainments, living early in the sixteenth century, have been ignorant of what had taken place in the twelfth; or that, by the latter end of this latter century, christianity had obtained the undisputed honour of having extirpated slavery from the western part of the European world.

From Spain and Italy I come to England. [I-40] The first importation of slaves from Africa by our countrymen was in the reign of Elizabeth, in the year 1562. This great princess seems on the very commencement of the trade to have questioned its lawfulness. She seems to have entertained a religious scruple concerning it, and, indeed, to have revolted at the very though: of it. She seems to have been aware of the evils to which its continuance might lead, or that, if it were sanctioned, the most unjustifiable means might be made use of to procure the persons of the natives of Africa. And in what light she would have viewed any acts of this kind, had they taken place, we may conjecture from this fact,—that when captain (afterwards Sir John) Hawkins returned from his first voyage to Africa and Hispaniola, whither he had carried slaves, she sent for him, and, as we learn from Hill’s Naval History, expressed her concern lest any of the Africans should be carried off without their free consent, declaring that “It would be detestable, and call down the vengeance of Heaven upon the undertakers.” Captain Hawkins promised to comply with the injunctions of Elizabeth in this respect. [I-41] But he did not keep his word; for when he went to Africa again, he seized many of the inhabitants and carried them off as slaves, which occasioned Hill, in the account he gives of his second voyage, to use these remarkable words:—“Here began the horrid practice of forcing the Africans into slavery, an injustice and barbarity, which, so sure as there is vengeance in heaven for the worst of crimes, will sometime be the destruction of all who allow or encourage it.” That the trade should have been suffered to continue under such a princess, and after such solemn expressions as those which she has been described to have uttered, can be only attributed to the pains taken by those concerned in it to keep her ignorant of the truth.

From England I now pass over to France. Labat, a Roman missionary, in his account of the isles of America, mentions, that Louis the Thirteenth was very uneasy when he was about to issue the edict, by which all Africans coming into his colonies were to be made slaves, and that this uneasiness continued, till he was assured, that the introduction of them in this capacity into his [I-42] foreign dominions was the readiest way of converting them to the principles of the christian religion.

These, then, were the first forerunners in the great cause of the abolition of the Slave-trade. Nor have their services towards it been of small moment. For, in the first place, they have enabled those, who came after them, and who took an active interest in the same cause, to state the great authority of their opinions and of their example. They have enabled them, again, to detail the history connected with these, in consequence of which circumstances have been laid open, which it is of great importance to know. For have they not enabled them to state, that the African Slave-trade never would have been permitted to exist but for the ignorance of those in authority concerning it—That at its commencement there was a revolting of nature against it—a suspicion—a caution—a fear—both as to its unlawfulness and its effects? Have they not enabled them to state, that falsehoods were advanced, and these concealed under the mask of religion, to deceive those who had the power to suppress it? Have they not enabled them [I-43] to state that this trade began in piracy, and that it was continued upon the principles of force? And, finally, have not they, who have been enabled to make these statements; knowing all the circumstances connected with them, found their own zeal increased and their own courage and perseverance strengthened; and have they not, by the communication of them to others, produced many friends and even labourers in the cause?

[I-44]

CHAPTER III.↩

Forerunners continued to 1787—divided from this time into four classes—First class consists principally of persons in Great Britain of various descriptions—Godwyn—Baxter—Tryon—Southern—Primatt—Montesquieu—Hutcheson—Sharp—Ramsay—and a multitude of others, whose names and services follow.

I have hitherto traced the history of the forerunners in this great cause only up to about the year 1640. If I am to pursue my plan, I am to trace it to the year 1787. But in order to show what I intend in a clearer point of view, I shall divide those who have lived within this period, and who will now consist of persons in a less elevated station, into four classes: and I shall give to each class a distinct consideration by itself.

Several of our old English writers, though they have not mentioned the African Slave-trade, or the slavery consequent upon it, in their respective works, have yet given their [I-45] testimony of condemnation against both. Thus our great Milton:—

“O execrable son, so to aspire

Above his brethren, to himself assuming

Authority usurpt, from God not given;

He gave us only over beast, fish, fowl,

Dominion absolute; that right we hold

By his donation;—but man over men

He made not lord, such title to himself

Reserving, human left from human free.”

I might mention bishop Saunderson and others, who bore a testimony equally strong against the lawfulness of trading in the persons of men, and of holding them in bondage, but as I mean to confine myself to those, who have favoured the cause of the Africans specifically, I cannot admit their names into any of the classes which have been announced.

Of those who compose the first class, defined as it has now been, I cannot name any individual who took a part in this cause till between the years 1670 and 1680. For in the year 1640, and for a few years afterwards, the nature of the trade and of the slavery was but little known, except to a few individuals, who were concerned in [I-46] them; and it is obvious that these would neither endanger their own interest nor proclaim their own guilt by exposing it. The first, whom I shall mention, is Morgan Godwyn, a clergyman of the established church. This pious divine wrote a Treatise upon the subject, which he dedicated to the then archbishop of Canterbury. He gave it to the world, at the time mentioned, under the title of “The Negros and Indians Advocate.” In this treatise he lays open the situation of these oppressed people, of whose sufferings he had been an eye-witness in the island of Barbadoes. He calls forth the pity of the reader in an affecting manner, and exposes with a nervous eloquence the brutal sentiments and conduct of their oppressors. This seems to have been the first work undertaken in England expressly in favour of the cause.

The next person, whom I shall mention, is Richard Baxter, the celebrated divine among the Nonconformists. In his Christian Directory, published about the same time as the Negros and Indians Advocate, he gives advice to those masters in foreign plantations, who have Negros and other slaves. In this [I-47] he protests loudly against this trade. He says expressly that they, who go out as pirates, and take away poor Africans, or people of another land, who never forfeited life or liberty, and make them slaves and sell them, are the worst of robbers, and ought to be considered as the common enemies of mankind; and that they, who buy them, and use them as mere beasts for their own convenience, regardless of their spiritual welfare, are fitter to be called demons than christians. He then proposes several queries, which he answers in a clear and forcible manner, showing the great inconsistency of this traffic, and the necessity of treating those then in bondage with tenderness and a due regard to their spiritual concerns.

The Directory of Baxter was succeeded by a publication called “Friendly Advice to the Planters: in three parts.” The first of these was, “A brief Treatise of the principal Fruits and Herbs that grow in Barbadoes, Jamaica, and other Plantations in the West Indies.” The second was, “The Negros Complaint, or their hard Servitude, and the Cruelties practised upon them by divers of [I-48] their Masters professing Christianity.” And the third was, “A Dialogue between an Ethiopian and a Christian, his Master, in America.” In the last of these, Thomas Tryon, who was the author, inveighs both against the commerce and the slavery of the Africans, and in a striking manner examines each by the touchstone of reason, humanity, justice, and religion.

In the year 1696, Southern brought forward his celebrated tragedy of Oronooko, by means of which many became enlightened upon the subject, and interested in it. For this tragedy was not a representation of fictitious circumstances, but of such as had occurred in the colonies, and as had been communicated in a publication by Mrs. Behn.

The person, who seems to have noticed the subject next was Dr. Primatt. In his “Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy, and on the Sin of Cruelty to Brute-animals,” he takes occasion to advert to the subject of the African Slave-trade. “It has pleased God,” says he, “to cover some men with white skins and others with black; but as there is neither merit nor demerit in complexion, the [I-49] white man, notwithstanding the barbarity of custom and prejudice, can have no right by virtue of his colour to enslave and tyrannize over the black man. For whether a man be white or black, such he is by God’s appointment, and, abstractedly considered, is neither a subject for pride, nor an object of contempt.”

After Dr. Primatt, we come to baron Montesquieu. “Slavery,” says he, “is not good in itself. It is neither useful to the master nor to the slave. Not to the slave, because he can do nothing from virtuous motives. Not to the master, because he contracts among his slaves all sorts of bad habits, and accustoms himself to the neglect of all the moral virtues. He becomes haughty, passionate, obdurate, vindictive, voluptuous, and cruel.” And with respect to this particular species of slavery he proceeds to say, “it is impossible to allow the Negros are men, because, if we allow them to be men, it will begin to be believed that we ourselves are not Christians.”

Hutcheson, in his System of Moral Philosophy, endeavours to show that he, who detains another by force in slavery, can make [I-50] no good title to him, and adds, “Strange that in any nation where a sense of liberty prevails, and where the Christian religion is professed, custom and high prospect of gain can so stupefy the consciences of men and all sense of natural justice, that they can hear such computations made about the value of their fellow-men and their liberty without abhorrence and indignation!”

Foster, in his Discourses on Natural Religion and Social Virtue, calls the slavery under our consideration “a criminal and outregeous violation of the natural rights of mankind.” I am sorry that I have not room to say all that he says on this subject. Perhaps the following beautiful extracts may suffice:

“But notwithstanding this, we ourselves, who profess to be Christians, and boast of the peculiar advantages we enjoy by means of an express revelation of our duty from heaven, are in effect these very untaught and rude heathen countries. With all our superior light we instil into those, whom we call savage and barbarous, the most despicable opinion of human nature. We, to the utmost of our power, weaken and dissolve [I-51] the universal tie, that binds and unites mankind. We practise what we should exclaim against as the utmost excess of cruelty and tyranny, if nations of the world, differing in colour and form of government from ourselves, were so possessed of empire, as to be able to reduce us to a state of unmerited and brutish servitude. Of consequence we sacrifice our reason, our humanity, our christianity, to an unnatural sordid gain. We teach other nations to despise and trample under foot all the obligations of social virtue. We take the most effectual method to prevent the propagation of the gospel, by representing it as a scheme of power and barbarous oppression, and an enemy to the natural privileges and rights of man.”

“Perhaps all that I have now offered may be of very little weight to restrain this enormity, this aggravated iniquity. However, I shall still have the satisfaction of having entered my private protest against a practice, which, in my opinion, bios that God, who is the God and Father of the Gentiles unconverted to christianity, most daring and bold defiance, and spurns at all the principles both of natural and revealed religion.”

[I-52]

The next author is sir Richard Steele, who, by means of the affecting story of Inkle and Yarico, holds up this trade again to our abhorrence.

In the year 1735, Atkins, who was a surgeon in the navy, published his Voyage to Guinea, Brazil, and the West-Indies, in his Majesty’s ships Swallow and Weymouth. In this work he describes openly the manner of making the natives slaves, such as by kidnapping, by unjust accusations and trials, and by other nefarious means. He states also the cruelties practised upon them by the white people, and the iniquitous ways and dealings of the latter, and answers their argument, by which they insinuated that the condition of the Africans was improved by their transportation to other countries.

From this time the trade beginning to be better known, a multitude of persons of various stations and characters sprung up, who by exposing it are to be mentioned among the forerunners and coadjutors in the cause.

Pope, in his Essay on Man, where he endeavours to show that happiness in the present depends, among other things, upon the hope of a future state, takes an opportunity [I-53] of exciting compassion in behalf of the poor African, while he censures the avarice and cruelty of his master:

“Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor’d mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk, or milky-way;

Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv’n

Behind the cloud-topt hill an humbler heav’n;

Some safer world in depth of woods embrac’d,

Some happier island in the watry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold.”

Thomson also, in his Seasons, marks this traffic as destructive and cruel, introducing the well-known fact of sharks following the vessels employed in it:

“Increasing still the sorrows of those storms,

His jaws horrific arm’d with three-fold fate,

Here dwells the direful shark. Lur’d by the scent

Of steaming crowds, of rank disease, and death,

Behold! he rushing cuts the briny flood,

Swift as the gale can bear the ship along,

And from the partners of that cruel trade,

Which spoils unhappy Guinea of her sons,

Demands his share of prey, demands themselves.

The stormy fates descend: one death involves

Tyrants and slaves; when straight their mangled limbs

Crashing at once, he dyes the purple seas

With gore, and riots in the vengeful meal.”

[I-54]

Neither was Richard Savage forgetful in his poems of the Injured Africans: he warns their oppressors of a day of retribution for their barbarous conduct. Having personified Public Spirit, he makes her speak on the subject in the following manner:—

“Let by my specious name no tyrants rise,

And cry, while they enslave, they civilize!

Know, Liberty and I are still the same

Congenial—ever mingling flame with flame!

Why must I Afric’s sable children see

Vended for slaves, though born by nature free,

The nameless tortures cruel minds invent

Those to subject whom Nature equal meant?

If these you dare (although unjust success

Empow’rs you now unpunish’d to oppress),

Revolving empire you and yours may doom—

(Rome all subdu’d—yet Vandals vanquish’d Rome)

Yes—Empire may revolt—give them the day,

And yoke may yoke, and blood may blood repay.”

Wallis, in his System of the Laws of Scotland, maintains, that “neither men nor governments have a right to sell those of their own species. Men and their liberty are neither purchaseable nor saleable.” And, after arguing the case, he says, “This is the law of nature, which is obligatory on all men, at all times, and in all places.—Would [I-55] not any of us, who should be snatched by pirates from his native land, think himself cruelly abused, and at all times entitled to be free? Have not these unfortunate Africans, who meet with the same cruel fate, the same right? Are they not men as well as we? And have they not the same sensibility? Let us not therefore defend or support an usage, which is contrary to all the laws of humanity.”

In the year 1750 the reverend Griffith Hughes, rector of St. Lucy, in Barbadoes, published his Natural History of that island. He took an opportunity, in the course of it, of laying open to the world the miserable situation of the poor Africans, and the waste of them by hard labour and other cruel means, and he had the generosity to vindicate their capacities from the charge, which they who held them in bondage brought against them, as a justification of their own wickedness in continuing to deprive them of the rights of men.

Edmund Burke, in his account of the European settlements, (for this work is usually attributed to him,) complains “that the Negroes in our colonies endure a slavery [I-56] more complete, and attended with far worse circumstances, than what any people in their condition suffer in any other part of the world, or have suffered in any other period of time. Proofs of this are not wanting. The prodigious waste, which we experience in this unhappy part of our species, is a full and melancholy evidence of this truth.” And he goes on to advise the planters for the sake of their own interest to behave like good men, good masters, and good Christians, and to impose less labour upon their slaves, and to give them recreation on some of the grand festivals, and to instruct them in religion, as certain preventives of their decrease.

An anonymous author of a pamphlet, entitled, An Essay in Vindication of the Continental Colonies of America, seems to have come forward next. Speaking of slavery there, he says, “It is shocking to humanity, violative of every generous sentiment, abhorrent utterly from the Christian religion—There cannot be a more dangerous maxim than that necessity is a plea for injustice, for who shall fix the degree of this necessity? What villain so atrocious, [I-57] who may not urge this excuse, or, as Milton has happily expressed it,

“and with necessity,

The tyrant’s plea, excuse his dev’lish deed?”

“That our colonies,” he continues, “want people, is a very weak argument for so inhuman a violation of justice—Shall a civilized, a Christian nation encourage slavery, because the barbarous, savage, lawless African hath done it? To what end do we profess a religion whose dictates we so flagrantly violate? Wherefore have we that pattern of goodness and humanity, if we refuse to follow it? How long shall we continue a practice which policy rejects, justice condemns, and piety revolts at?”

The poet Shenstone, who comes next in order, seems to have written an Elegy on purpose to stigmatize this trade. Of this elegy I shall copy only the following parts:

“See the poor native quit the Libyan shores,

Ah! not in love’s delightful fetters bound!

No radiant smile his dying peace restores,

No love, nor fame, nor friendship heals his wound.

“Let vacant bards display their boasted woes;

Shall I the mockery of grief display?

No; let the muse his piercing pangs disclose,

Who bleeds and weeps his sum of life away!

[I-58]

“On the wild heath in mournful guise he stood

Ere the shrill boatswain gave the hated sign;

He dropt a tear unseen into the flood,

He stole one secret moment to repine—

“Why am I ravish’d from my native strand?

What savage race protects this impious gain?

Shall foreign plagues infest this teeming land,

And more than sea-born monsters plough the main?

“Here the dire locusts’ horrids warms prevail;

Here the blue asps with livid poison swell;

Here the dry dipsa writhes his sinuous mail;

Can we not here secure from envy dwell?

“When the grim lion urg’d his cruel chase,

When the stern panther sought his midnight prey,

What fate reserv’d me for this Christian race?

O race more polish’d, more severe, than they—

“Yet shores there are, bless’d shores for us remain,

And favour’d isles, with golden fruitage crown’d,

Where tufted flow’rets paint the verdant plain,

And ev’ry breeze shall med’cine ev’ry wound.”

In the year 1755, Dr. Hayter, bishop of Norwich, preached a sermon before the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, in which he bore his testimony against the continuance of this trade.

Dyer, in his poem called The Fleece, expresses his sorrow on account of this barbarous trade, and looks forward to a day of [I-59] retributive justice on account of the introduction of such an evil.

In the year 1760, a pamphlet appeared, entitled, “Two Dialogues on the Mantrade, by John Philmore.” This name is supposed to be an assumed one. The author, however, discovers himself to have been both an able and a zealous advocate in favour of the African race.

Malachi Postlethwaite, in his Universal Dictionary of Trade and Commerce, proposes a number of queries on the subject of the Slave-trade. I have not room to insert them at full length. But I shall give the following as the substance of some of them to the reader: “Whether this commerce be not the cause of incessant wars among the Africans—Whether the Africans, if it were abolished, might not become as ingenious, as humane, as industrious, and as capable of arts, manufactures, and trades, as even the bulk of Europeans—Whether, if it were abolished, a much more profitable trade might not be substituted, and this to the very centre of their extended country, instead of the trifling portion which now subsists upon their coasts—And whether [I-60] the great hindrance to such a new and advantageous commerce has not wholly proceeded from that unjust, inhuman, unchristian-like traffic, called the Slave-trade, which is carried on by the Europeans.” The public proposal of these and other queries by a man of so great commercial knowledge as Postlethwaite, and by one who was himself a member of the African Committee, was of great service in exposing the impolicy as well as immorality of the Slave-trade.

In the year 1761, Thomas Jeffery published an account of a part of North America, in which he lays open the miserable state of the slaves in the West Indies, both as to their clothing, their food, their labour, and their punishments. But, without going into particulars, the general account he gives of them is affecting: “It is impossible,” he says, “for a human heart to reflect upon the slavery of these dregs of mankind, without in some measure feeling for their misery, which ends but with their lives—Nothing can be more wretched than the condition of this people.”

Sterne, in his account of the Negro girl in his Life of Tristram Shandy, took decidedly [I-61] the part of the oppressed Africans. The pathetic, witty, and sentimental manner, in which he handled this subject, occasioned many to remember it, and procured a certain portion of feeling in their favour.

Rousseau contributed not a little in his day to the same end.

Bishop Warburton preached a sermon in the year 1766, before the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, in which he took up the cause of the miserable Africans, and in which he severely reprobated their oppressors. The language in this sermon is so striking, that I shall make an extract from it. “From the free savages,” says he, “I now come to the savages in bonds. By these I mean the vast multitudes yearly stolen from the opposite continent, and sacrificed by the colonists to their great idol the god of gain. But what then, say these sincere worshippers of mammon? They are our own property which we offer up.—Gracious God! to talk, as of herds of cattle, of property in rational creatures, creatures endued with all our faculties, possessing all our qualities but that of colour, our brethren both by nature and grace, shocks all the [I-62] feelings of humanity, and the dictates of common sense! But, alas! what is there, in the infinite abuses of society, which does not shock them? Yet nothing is more certain in itself and apparent to all, than that the infamous traffic for slaves directly infringes both divine and human law. Nature created man free, and grace invites him to assert his freedom.”

“In excuse of this violation it hath been pretended, that though indeed these miserable outcasts of humanity be torn from their homes and native country by fraud and violence, yet they thereby become the happier, and their condition the more eligible. But who are you, who pretend to judge of another man’s happiness; that state, which each man under the guidance of his Maker forms for himself, and not one man for another? To know what constitutes mine or your happiness is the sole prerogative of him who created us, and cast us in so various and different moulds. Did your slaves ever complain to you of their unhappiness amidst their native woods and deserts? or rather let me ask, Did they ever cease complaining of their condition under you their lordly masters, [I-63] where they see indeed the accommodations of civil life, but see them all pass to others, themselves unbenefited by them? Be so gracious then, ye petty tyrants over human freedom, to let your slaves judge for themselves, what it is which makes their own happiness, and then see whether they do not place it in the return to their own country, rather than in the contemplation of your grandeur, of which their misery makes so large a part; a return so passionately longed for, that, despairing of happiness here, that is, of escaping the chains of their cruel task-masters, they console themselves with feigning it to be the gracious reward of heaven in their future state”—

About this time certain cruel and wicked practices, which must now be mentioned, had arrived at such a height, and had become so frequent in the metropolis, as to produce of themselves other coadjutors to the cause.