GEORGE BUCHANAN,

Dialogue concerning the Rights of the Crown of Scotland.

Translated into English by Robert MacFarlan (1799)

[Created: 31 October, 2024]

[Updated: 31 October, 2024] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

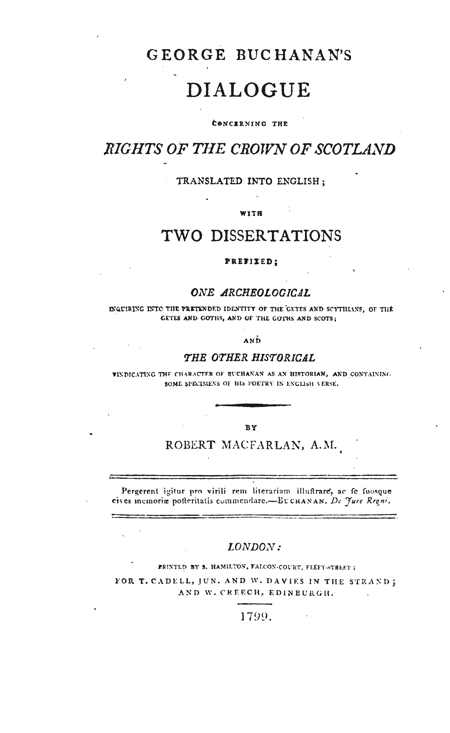

, George Buchanan's Dialogue concerning the Rights of the Crown of Scotland. Translated into English; with two dissertations prefixed; one archeological inquiring into the pretended identity of the Getes and Scythlans, of the Getes and Goths, and of the Goths and Scots; and the other historical vindicating the character of Buchanan as an historian, and containing some specimens of his poetry in english verse. By Robert Macfarlan, A.M. (London : Printed by S. Hamilton, Falcon-Court, Fleet-Street; for T. Cadell, jun. and W. Davies in the strand; and W. Creech, Edinburgh, 1799).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1799-Buchanan_DeJureRegni/Buchanan_Dialogue1799-ebook.html

George Buchanan's Dialogue concerning the Rights of the Crown of Scotland. Translated into English; with two dissertations prefixed; one archeological inquiring into the pretended identity of the Getes and Scythlans, of the Getes and Goths, and of the Goths and Scots; and the other historical vindicating the character of Buchanan as an historian, and containing some specimens of his poetry in english verse. By Robert Macfarlan, A.M. (London : Printed by S. Hamilton, Falcon-Court, Fleet-Street; for T. Cadell, jun. and W. Davies in the strand; and W. Creech, Edinburgh, 1799).

Editor's Note: We have only put online Buchanan's "Dialogue" not MacFarlan's essays. The "Dialogue" is pp. 81-205.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Table of Contents

DE JURE REGNI APUD SCOTOS;

A DIALOGUE CONCERNING THE RIGHTS OF THE CROWN IN SCOTLAND.

[81]

GEORGE BUCHANAN WISHES MUCH GOOD HEALTH TO JAMES THE SIXTH, KING OF THE SCOTS.↩

Several years ago, when public affairs were in the greatest confusion, I wrote on the prerogative of the Scottish crown a Dialogue, in which I endeavoured to explain from their very cradle, if I may use the expression, the mutual rights of our kings and of their subjects. Though that book seemed to have been serviceable at the time, by shutting the mouths of certain persons, who with importunate clamours rather inveighed against the existing state of things than weighed what was right in the scale of reason, yet influenced by the return of a little tranquillity, I also laid down my arms with pleasure on the altar of public concord. But having lately by accident lighted on this composition among my papers, and thought it interspersed with many remarks necessary to a person raised like you to an eminence so interesting to mankind, I have judged its publication expedient, that it might both testify my zeal for your service and also remind you of your duty to the community. Many circumstances also assure me that my endeavour on this occasion will not be fruitless; especially your age not yet corrupted by wrong opinions, and a genius above your years spontaneously urging you to everything noble; and an easy flexibility in obeying not only your preceptors [82] but also all wise monitors; and that judgment and sagacity in disquisition, which prevent you from allowing great weight to authority, when it is not supported by solid arguments. I see also that, by a kind of natural instinct, you so abhor flattery, the vile nurse of tyranny and the very pest of legal sovereignty, that you hate the solecisms and barbarisms of courtiers no less than they are relished and affected by those who in their own eyes appear connoisseurs in every species of elegance, and, as if they were delicate seasonings to conversation, interlard every sentence with majesties, lordships, excellencies, and, if it be possible, with other expressions of a still more offensive savour. Though you be at present secured from this error, both by the goodness of your natural disposition and by the instructions of your governors, yet I cannot help being somewhat afraid that the blandishments of that pander of vice, evil communication, should give a wrong bias to a mind that is yet so pliant and tender; especially as I am not ignorant with what facility our other senses yield to seduction. This treatise, therefore, I have sent you not only as a monitor, but also as an importunate and even impudent dun; that in this critical turn of life it may guide you beyond the rocks of flattery, and not only give you advice, but also keep you in the road which you so happily entered, and, in case of any deviation, replace you in the line of your duty. If you obey its directions, you will insure to yourself and to your family in the present life temporal tranquillity, and in the future, eternal glory. Farewell.

At Stirling on the 10th of January in the year of the Christian Era 1579.

[83]

A DIALOGUE CONCERNING THE RIGHTS OF THE CROWN IN SCOTLAND.↩

Translated from the Latin Original of George Buchanan

When, upon Thomas Maitland’s return lately from the continent, I had questioned him minutely about the state of affairs in France, I began, out of my attachment to his person, to recommend to him a perseverance in that career to glory which he had so happily begun, and to inspire him with the best hopes of the progress and result of his studies. For, if I, with moderate talents, with hardly any fortune, and in an illiterate age, had still maintained such a conflict with the iniquity of the times, as to be thought to have achieved something, assuredly those who were born in happier days, and possess time, wealth and genius in abundance, ought not to be deterred from so honourable a purpose by its labour; and, when aided by so many resources, cannot reasonably yield to despair. They should therefore proceed to use every effort in communicating splendour to literature, and in recommending themselves and their countrymen to the notice of posterity. If [84] they continued for a little their joint exertions, the consequence would be, that they would eradicate from the minds of men an opinion, that in the frigid regions of the globe the learning, politeness and ingenuity of the inhabitants diminish in proportion to their distance from the sun; for, though nature may have favoured the Africans, Egyptians, and most other nations with quicker conceptions and greater keenness of intellect, yet she has been so unkind to no tribe as to have entirely precluded it from all access to virtue and glory.

Here, when, according to his usual modesty, he had spoken of himself with diffidence, but of me with more affection than truth, the course of conversation at last led us so far, that, when he had questioned me concerning the convulsed state of our country, and I had made him such an answer as I thought calculated for the time, I began, in my turn, to ask him what sentiments either the French, or any strangers that he met in France, entertained concerning Scottish affairs; for I had no doubt that the novelty of the events would, as is usual, have furnished occasion and matter for political discussions.

“Why,” says he, “do you address to me such a question? For, since you know the whole train of events, and are not unacquainted with what most people say, and almost all think, you may easily conjecture, from the internal conviction of your own mind, what is, or at least what ought to be, the opinion of all mankind.”

B. But the more distant foreign nations are, and the fewer causes they have from that distance for anger, for hatred, for love, and for other passions likely to make the mind swerve from truth, the more ingenuous and open they commonly are in judging, and the more freely they speak what they [85] think; and this very freedom of speech and mutual interchange of thought removes much obscurity, disentangles many knotty points, converts doubts into certainties, and may shut the mouths of the dishonest and designing, and instruct the weak and unenlightened.

M. Would you have me be ingenuous in my answer?

B. Why not?

M. Though I was strongly actuated by a desire of revisiting, after a long absence, my country, my parents, my relations and friends, yet nothing inflamed this passion so much as the language of the untutored multitude. For, however firm I had thought the temper of my mind, rendered either by the effects of habit or by the precepts of philosophy, yet, when the event now under consideration occurred, I could not, by some fatality, conceal its softness and effeminacy. For, as the shocking enormity here lately exhibited was unanimously detested by all orders of men, and the perpetrator still uncertain, the vulgar, always swayed rather by momentary impulse than by sound discretion, imputed a fault of a few to the many; and the common hatred to the misdeed of private individuals so overwhelmed the whole nation, that even those who stood most remote from suspicion laboured under the infamy of other men’s crimes. Therefore, till this storm of calumny should subside into a calm, I readily took shelter in this port, where, however, I fear that I have struck against a rock.

B. For what reason, I beseech you?

M. Because the minds of all men, being already heated, seem to me likely to be so much inflamed by the atrocity of the late crime as to leave no room for defence. For how can I resist the attack [86] not only of the uninformed multitude, but even of those who assume the character of politicians, while both will exclaim that our ferocious rage was not satiated by murdering, with unparalleled cruelty, an innocent youth, but exhibited a new example of barbarity in the persecution of women, a sex that is spared even by hostile armies at the capture of cities? From what horror, indeed, will any dignity or any majesty deter men who are guilty of such outrage to their princes? After these enormities, whom will justice, morality, law, respect for sovereignty or reverence for legal magistracy, restrain through shame or check through fear? When the exercise of the supreme executive power is become the ridicule of the lowest rabble, when trampling upon every distinction between right and wrong, between honour and dishonour, men degenerate, almost by common consent, into savage barbarity. To these and still more atrocious charges I know that I shall be forced, upon my return to France, to listen, as the ears of all have in the meantime been so thoroughly shut as to be susceptible of no apology, nor even of a satisfactory defence.

B. But I will easily relieve you from this apprehension, and clear our nation from so false an imputation. For, if foreigners so heartily execrate the heinousness of the antecedent crime, where is the propriety of reprobating the severity of the subsequent punishment? Or, if they are vexed at the degradation of the queen, the former must necessarily meet with their approbation. Do you, therefore, choose to which of the two cases you wish to attach guilt; for neither they nor you, if you mean to be consistent, can either praise or dispraise both.

[87]

M. The murder of the king I certainly detest and abominate, and am glad that the odium of conscious guilt does not fall upon the public, but is attributable to the villany of a few desperadoes; but the latter act I cannot either wholly approve or disapprove. The detection by sagacity and industry of the most nefarious deed mentioned in any history, and the vengeance awaiting the wicked perpetrators from open hostilities, appear to me glorious and memorable achievements. But with the degradation of the chief magistrate, and with the contempt brought upon the royal name, which has been among all nations constantly held sacred and inviolable, I know not how all the nations of Europe will be effected, especially those that live under a regal government. As for myself, though not ignorant of the adverse pretences and allegations, I feel violent emotions either from the magnitude or novelty of the event; and the more so that some of its authors are connected with me by the closest intimacy.

B. Now, methinks, I can nearly discern what it is that affects you, but not perhaps so much as it touches those iniquitous estimators of other men’s merit, to whom you think satisfaction is due. Of those who will violently condemn the forcible seizure of the queen, I reckon three principal divisions. One is peculiarly pernicious, as it comprehends the panders to the lusts of tyrants, wretches who think no act unjust or dishonourable by which they conceive that kings may be gratified, and who measure every thing not by its intrinsic value, but by the passions of their masters. These are such venal devotees to the desires of another that they have retained freedom neither of speech nor of action. From this band proceeded the banditti, who, without any cause [88] of enmity, and merely with the hopes of preferment and power at court, sacrificed, in the most cruel manner, an innocent youth to another’s lust. While these hypocrites pretend to lament the fate of the queen, and to sigh and groan over her miseries, they mean only to provide for their own security, and really grieve at seeing the enormous reward for their execrable villany, which they had devoured in imagination, snatched out of their jaws. This sort of people ought, therefore, in my opinion, to be chastised not so much by words as by the severity of the laws and by the force of arms. Others look totally to their own affairs. These, though in other respects by no means bad men, are not vexed, as they would wish us to think, at the injury done to the public, but at their own domestic losses; and therefore seem to me to need consolation rather than any remedy derivable from reason or from law. The remainder consist of the rude and undistinguishing multitude, who wonder and gape at every novelty, who censure almost every occurrence, and think hardly anything right but what is either their own act or what is done under their own eye. For every departure from the practice of their ancestors they think a proportionate deviation from justice and equity. These being swayed neither by malice nor by envy, nor by any regard to self-interest, are generally susceptible of instruction and of being reclaimed from error, and commonly yield to the force of reasoning and conviction; a truth of which we now have, and formerly often had, experience in the case of religion; for

Where’s the savage we to tame should fear,

If he to culture lend a patient ear?

[89]

M. That remark we have more than once found to be perfectly just.

B. What if, in order to silence this multitude, you should ask the most clamorous and importunate their opinion concerning the fate of Caligula, of Nero and of Domitian; I presume that none of them would be so servilely attached to the regal name as not to acknowledge that they were justly punished?

M. Possibly what you say may be true. But the same persons will immediately exclaim that they do not complain of the punishment of tyrants, but feel indignant at the undeserved calamities of legal sovereigns.

B. Do not you then see how easily the multitude may be pacified?

M. Not yet. The matter seems to require more elucidation.

B. I will, by a few words, make it intelligible. The vulgar, according to you, approve the murder of tyrants, but compassionate the sufferings of kings. Do not you think, then, that if they should clearly understand the difference between a tyrant and a king, it will be possible, in most particulars, to alter their opinion?

M. Were all to acknowledge the justice of killing tyrants, it would open a wide inlet for the diffusion of light upon the subject. But some men there are, and those of no contemptible authority, who, though they subject legal sovereigns to penal laws, contend for the sacredness of tyrants; and, though their decision is certainly in my opinion absurd, yet they are ready to fight for their government, however extravagant and intolerable, as for their own altars and hearths.

B. I also have more than once met with various individuals who obstinately maintained the same [90] doctrine; but whether they were right or wrong we shall elsewhere more commodiously examine. In the meantime, if you will, let this point be taken for granted, upon condition that, if you do not afterwards find it sufficiently demonstrated, you may at pleasure resume the subject for discussion.

M. Upon these terms I have no objection.

B. We shall then establish it as an axiom that a king and a tyrant are contraries.

M. Be it so.

B. He then who has explained the origin and the causes of creating kings, and the duties of kings to their subjects, and of subjects to their kings, must be allowed to have, by the contrast, nearly explained whatever relates to the nature of a tyrant.

M. I think so.

B. And when the picture of each is exhibited, do not you think that the people will also understand what is their duty to each?

M. Nothing is more likely.

B. But in things extremely dissimilar, and withal of the same general class, there may be certain dissimilarities very apt to lead the inadvertent into error.

M. That may indisputably be the case, and particularly when an inferior character finds it easy to assume the appearance of a superior, and studies nothing so much as to impose upon ignorance.

B. Have you in your mind any distinct picture of a king and a tyrant, for, if you have, you will ease me of much labour?

M. The figure of both, which I have in my mind, I could certainly delineate with ease; but it would appear to your eyes, I fear, rude and misshapen. Therefore, lest, by forcing you to rectify my errors, the conversation should exceed the [91] due bounds, I choose rather to hear the sentiments adopted by you, who have the advantage of me both in age and experience, and not only know the opinions of others, but have also visited in person many states, and noted their manners and customs.

B. That I shall do, and with pleasure; nor shall I expound so much my own as the opinion of the ancients, that more weight and authority may accompany my words, as not being framed for the present occasion, but extracted from the doctrines of those who were entirely unconnected with this controversy, and delivered their sentiments with no less eloquence than brevity, without hatred, without favour or envy, for which they could not have the most distant motive; and I shall adopt principally the opinions not of those who grew old in the shades of inactivity, but of men who were in well-regulated states distinguished at home and abroad for wisdom and virtue. But, before I produce their testimony, I wish to ask you a few questions, that, when we have agreed upon some points of no small importance, I may not be compelled to deviate from my intended course, and to dwell either upon the explanation or confirmation of matters that are evident, and almost acknowledged truths.

M. Your plan I approve; and, therefore, if you have any question to ask, proceed?

B. Is it your opinion that there was a time when men lived in huts and even in caves, and strolled at random, without laws, without settled habitations, like mere vagrants, uniting in herds as they were led by fancy and caprice, or invited by some convenience and common advantage?

M. That is certainly my firm belief; for it is not only consonant to the order of nature, but also sanctioned by almost all the histories of all nations. Of [92] that rude and uncultivated life we have, from Homer’s pen, a picturesque description soon after the Trojan war among the Sicilians:—

By them no statute and no right was known,

No council held, no monarch fills the throne;

But high on hills or airy cliffs they dwell,

Or deep in caverns or some rocky cell;

Each rules his race, his neighbor not his care,

Heedless of others, to his own severe.

At the same period, too, Italy is said to have been equally uncultivated; so that, from the state of the most fertile regions of the globe, it is easy to form a conjecture that the rest were nothing but wild and desolate wastes.

B. But which of the two do you think most conformable to nature; that vagrant and solitary life, or the social and unanimous assemblage of men?

M. Undoubtedly the unanimous assemblage of men, whom

Utility herself, from whom, on earth,

Justice and equity derive their birth,

first collected into masses and taught,

Fenc’d by one wall, and by one key and bar,

From open’d gates to pour the tide of war.

B. What! do you imagine that utility was the first and principal cause of human union?

M. Why not? since the lesson inculcated by the greatest sages is, that men were made by nature for men.

B. To certain individuals, indeed, utility seems to have great influence, both in the formation and in the maintenance of society. But, if I am not mistaken, their assemblage claims a much higher [93] origin, and the bond of their union is of a much earlier and more venerable date. For, if every individual were to pay attention only to his own interest, there is ground for suspecting, I fear, that this very utility would rather dissolve than unite society.

M. That observation may, perhaps, be true. But I should be glad to hear what is your other source of human association.

B. It is a certain innate propensity, not only in men, but also in other animals of the gentler tribes, to associate readily, even without the allurements of utility, with beings of their own species. But of the brute creation it is not our present business to treat. Men we certainly find so deeply impressed, and so forcibly swayed by this natural principle, that, if any of them were to enjoy, in abundance, everything that is calculated either for the preservation and health of the body, or for the pleasure and amusement of the mind, he must, without human intercourse, experience life to be a burden. This is such a notorious truth that even the persons who, from a love of science and a desire of investigating truth, have retired from the bustle of the world and lived recluse in sequestered retreats, have neither been able, for a length of time, to bear a perpetual exertion of mind, nor, upon discovering the necessity of relaxation, to remain immured in solitude, but readily produced the very result of their studies; and, as if they had laboured for the common good, added the fruit of their labours to the common stock. Hence it is my opinion, that if any person be so attached to solitude as to shun and fly the society of men, he is actuated rather by a disease of the mind than a principle of nature. Such, according to report, was Timon of Athens, and Bellerophon of Corinth,

[94]

A wretch, who, preying in corrosive pain

On his own vitals, roam’d the Aleian plain

With comfortless and solitary pace,

Shunning the commerce of the human race.

M. Here our sentiments are not far from coincidence. But the term nature, adopted by you, is an expression, which, from habit, I often use rather than understand; and it is applied by others so variously, and to such a multitude of objects, that I am generally at a loss about the idea which it conveys.

B. At present I certainly wish nothing else to be understood by it but the light infused into our minds by the divinity; for, since God created this dignified animal

Erect, of deeper reach of thought possess’d,

And fit to be the lord of all the rest.

he not only bestowed upon his body eyes, by whose guidance he might shun what is adverse, and pursue what is adapted to his condition, but also presented to his mind a kind of light, by which he might distinguish vice and infamy from virtue and honour. This power some call nature, some the law of nature: I certainly hold it to be divine, and am thoroughly persuaded that

Nature and wisdom’s voices are the same.

Of this law, too, we have from God a kind of abridgement, comprehending the whole in a few words, when he commands us to love him with all our heart, and our neighbours as ourselves. The sacred volumes, in all the books which relate to the formation of mortals, contain hardly anything else but an explanation of this law.

M. Do you then conceive that human society derives its origin not from any orator or lawyer [95] that collected the dispersed tribes of men, but from God himself?

B. That is positively my opinion; and, in the words of Cicero, I think that nothing done upon earth is more acceptable to the sovereign Deity, that rules this world, than assemblages of men called states, and united upon principles of justice. The different members of these states politicians wish to have connected by ties similar to the coherence subsisting between all the limbs of our body, to be cemented by mutual good offices, to labour for the general interest, to repel dangers and secure advantages in common, and, by a reciprocation of benefits, to conciliate the affections of the whole community.

M. You do not then assign utility as the cause of men’s union in society, but the law implanted in our minds by God at our birth, which you hold to be a much higher and more divine origin?

B. I admit of utility as one cause, but not as the absolute mother of justice and equity, as some would have her; but rather as her handmaid, and one of the guardians of a well-regulated community.

M. Here also I have no difficulty in expressing my concurrence and assent.

B. Now as our bodies, which consist of repugnant principles, are liable to diseases, that is, to passions and certain internal commotions; so in like manner must those larger bodies called states, as they are composed of different, and in some measure, of incompatible ranks, conditions, and dispositions of men, and of men, too,

Who cannot, with a fixed and steady view,

Even for an hour a single plan pursue.

[96]

Hence, the latter must certainly, like the former, come to a speedy dissolution, unless their tumults are calmed by a kind of physician, who, adopting an equable and salutary temperament, braces the weaker parts by fomentations, checks the redundant humours, and provides for the several members, so that neither the feebler parts may waste through want, nor the stronger grow too luxuriant through excess.

M. These would be the consequences that must inevitably ensue.

B. By what name shall we qualify him who shall perform the part of physician to the body politic?

M. About the name I am not very anxious; but such a personage, whatever his name may be, I hold to be of the first excellence, and to have the strongest resemblance to the divinity. In this respect much forecast seems discovered in the wisdom of our ancestors, who distinguished an office so honourable in its own nature by a very splendid name. For you mean, I suppose, a king, a term, of which the import is such, that it renders a thing of the most excellent and transcendent nature almost visible to our eyes.

B. You judge rightly, for by that appellation we address the Deity; since we have not a more magnificent title to express the pre-eminence of his excellent nature, nor one better adapted for expressing his paternal care and affection. Why should I collect other words that are metaphorically used to signify the office of a king, such as father, shepherd of the people, guide, prince, and governor? The latest intention of all these expressions is to show that kings were made not for themselves but for the people. And, now that we seem agreed [97] about the name, let us, if you please, discuss the office, still treading the path which we have hitherto pursued.

M. What path I beseech you?

B. You recollect what has been just said, that states have a great resemblance to the human body, civil commotions to diseases, and kings to physicians. If therefore we understand the business of a physician, we shall not be far, I presume, from comprehending the duty of a king.

M. It my be so; for, by the comparative view which you have exhibited, they appear to have not only a great resemblance, but even a strong affinity.

B. Do not expect that I should here discuss every minute particular; for it is what is neither allowed by the limits of our time, nor required by the nature of the subject. But, if I show you that there is a striking similarity in the most prominent features, your own imagination will readily suggest what is omitted, and complete the picture.

M. Proceed, as you have begun.

B. Each seems also to have the same object in view.

M. What object?

B. The preservation of the body committed to his care.

M. I understand. For the one ought, as far as the nature of the case will admit, to maintain the human body, and the other the body politic, in a sound state; and, when they happen to be affected with a disease, to restore them to good health.

B. Your conception of the matter is just; for the office of each is twofold,—the maintenance of a sound, and the recovery of a distempered constitution.

M. Such is my idea.

B. For in both cases the diseases are similar.

[93]

M. So they seem.

B. For both are injured by a certain redundance of what is noxious, and by a deficiency of what is salutary; and they are both cured nearly by a similar process, either by nursing, or gently cherishing the body when emaciated, or relieving it when full and overburdened by the discharge of superfluities, and by moderate exercise and labour.

M. Such is the fact. But there seems to be this difference, that in the one the humours, in the other the morals, must be duly tempered.

B. You are perfect master of the subject; for the body politic, like the natural, has its peculiar kind of temperament, which I think we may, with the greatest propriety, denominate justice; since it is she that provides for its distinct members, and makes them perform their duties with uniformity. Sometimes by the operation of bleeding, sometimes by the discharge of noxious matter, she, by a kind of evacuation, expels redundancies; sometimes she rouses despondence and pusillanimity, and administers consolation to diffidence, and reduces the whole body to the temper mentioned above, and exercises it, when thus reduced, by suitable labours; so that, by a regular and due intermixture of labour and rest, she preserves, as far as the thing is possible, the renovated constitution.

M. To all your positions I would readily assent, had you not made justice the temperament of the body politic; for, by its very name and profession, temperance seems rightfully entitled to that office.

B. I think it of no great moment on which of the two you confer this honour. For, as all the virtues, of which the energy is visible in action, consist in the observation of a due and uniform medium, they are so mutually interwoven and [99] connected, that they seem all to have but one object, the moderation of the passions. Under whatever general head it may be classed, it is of little importance which of the two names you adopt; and yet that moderation, which is exerted in common affairs and in the ordinary commerce of life, may, in my opinion, be with the greatest propriety denominated justice.

M. Here I have no difficulty in yielding my assent.

B. Now, I imagine that the intention of the ancients in creating a king was, according to what we are told of bees in their hives, spontaneously to bestow the sovereignty on him who was most distinguished among his countrymen for singular merit, and who seemed to surpass all his fellows in wisdom and equity.

M. That is probably the fact.

B. But what must be done, if no such person can be found in the community?

M. By the law of nature mentioned before, an equal has neither the power nor right of assuming authority over his equals; for I think it but justice that among persons in other respect equal, the returns of command and obedience should also be equal.

B. But, if the people, from a dislike to an ambitious canvass every year, should choose to elect as king an individual not possessed indeed of every regal virtue, but still eminent for nobility, for wealth or military glory, might not he, with the greatest justice, be deemed a king?

M. Undoubtedly; for the people have a right of investing whom they please with the sovereign power.

B. Suppose that we should employ, for the cure of diseases, a man of considerable acuteness, but still [100] not possessed of extraordinary skill in the medical art, must we directly, upon his election by the generality, consider him as a physician?

M. By no means. For learning and experience in many arts, and not votes, constitute a physician.

B. What do you think of the artists in the other professions?

M. I think that the same reasoning is applicable to them all.

B. Do you believe that it requires any art to discharge the functions of a king?

M. Why should I not?

B. Can you give any reason for your belief?

M. I think I can; and it is that which is peculiar to all the arts.

B. What reason do you mean?

M. All the arts certainly originated in experience. For, while most people proceeded at random and without method in the performance of many actions, which others completed with superior skill and address, men of discernment, having remarked the results on both sides, and weighed the causes of these results, arranged several classes of precepts, and called each class an art.

B. By the means, therefore, of similar remarks, the art of sovereignty may be described as well as that of medicine?

M. That I think possible.

B. On what precepts then must it be founded?

M. I am not prepared to give you a satisfactory answer.

B. Perhaps its comparison with other arts may lead to its comprehension.

M. In what manner?

B. Thus. There are certain precepts peculiar to grammar, to medicine, and to agriculture.

[101]

M. I comprehend.

B. May we not call these precepts of grammar and medicine also arts and laws, and so on in other cases?

M. So I certainly think.

B. What do you think of the civil law? Is it not a system of precepts calculated for sovereigns?

M. So it seems.

B. Ought it not then to be understood by him who would be created a king?

M. The inference appears to be unavoidable.

B. What shall we then say of him who does not understand it? Do you conceive that, even after his nomination by the people, he shall not be called king?

M. Here you reduce me to a dilemma; for, to make my answer compatible with the preceding concessions, I must affirm that the suffrages of the people can no more make a king than any other artist.

B. What, then, do you think ought to be done in this case? For, if the person elected by common suffrage is not a king, I fear that we are not likely to have any legal sovereign.

M. I also am not without the same fear.

B. Is it your pleasure, then, that the position just laid down in comparing the arts should be discussed with greater minuteness?

M. Be it so, if you think it necessary.

B. Did we not, in the several arts, call the precepts of the several artists laws?

M. We did.

B. But I fear that we did not then use sufficient circumspection.

M. Why so?

B. Because it seems an absurdity to suppose that he who understands any art should not be an artist.

[102]

M. It is an absurdity.

B. Ought we not therefore to consider him, who can perform what belongs to art, an artist, whether it proceeds from the spontaneous impulse of nature, or from an habitual facility acquired by a constant repetition of similar acts?

M. I think so.

B. Him, then, who possesses either the method or the skill to do anything rightly, we may term an artist, if he has by practice acquired the requisite power?

M. With more propriety, undoubtedly, than the other who understands only the bare precepts, without practice and experience.

B. The precepts, then, are not to be considered as the art?

M. By no means; but rather the semblance of art, or, more nearly still, its shadow.

B. What then is that directing power in states that we are to call either the art or science of politics.

M. I suppose that you mean the providential wisdom, from which, as a fountain, all laws calculated for the benefit of human society must flow.

B. You have hit the mark. Therefore, if any man should possess this wisdom in the highest degree of perfection, we might call him a king by nature, not by suffrage, and invest him with unlimited power. But, if no such person can be found, we must be satisfied with the nearest approach to this excellency of nature, and, in its possessor grasping a certain resemblance of the desired reality, call him king.

M. Let us honour him with that title, if you please.

B. And, because there is reason to fear that he may not have sufficient firmness of mind to resist [105] those affections which may, and often do, cause deviations from rectitude, we shall give him the additional assistance of law, as a colleague, or rather as a regulator of his passions.

M. It is not, then, your opinion, that a king should in all matters be invested with arbitrary power?

B. By no means; for I recollect that he is not only a king, but also a man erring much through ignorance, offending much through inclination, and much almost against his will; as he is an animal readily yielding to every breath of favour or hatred. This imperfection of nature too is generally increased by the possession of office; so that here, if anywhere, I recognize the force of the sentiment in the comedy, when it says, that “by unrestrained authority we all become worse.” For this reason legislative sages supplied their king with law, either to instruct his ignorance or to rectify his mistakes. From these remarks you may, I presume, conceive, as in a typical representation, what my idea is of a genuine king’s duty.

M. In whatever regards the creation of kings, their name and their office, you have given me entire satisfaction; and yet, if you wish to make any additions, I am ready to listen. But, though my imagination hurries on with eagerness to the remainder of your discussion, one circumstance, which through your whole discourse gave me some offence, must not pass in silence; and it is this, that you seemed to be a little too hard upon kings; an act of injustice of which I have before frequently suspected you, when I heard the ancient republics and the modern state of Venice become in your mouth the subjects of extravagant encomiums.

B. In this case you did not form a just idea of my sentiments; for, among the Romans, the [104] Massilians, the Venetians, and others who held the directions of the laws to be more sacred than the commands of their kings, it is not so much the diversity as the equity of their civil administration that I admire; nor do I think it of much consequence whether the supreme magistrate be called kind, duke, emperor, or consul, if it be observed as an invariable maxim, that it was for the express purpose of maintaining justice and equity that he was invested with the magistracy. For, if the plan of government be founded on law, there is no just reason for disputing about its name. The person whom we call the Doge of Venice is nothing else but a legal sovereign; and the first Roman consuls retained not only the ensigns but also the powers of the ancient kings. The only difference was that, as, to your knowledge, was the case with the perpetual kings of the Lacedæmonians, the presiding magistrates were two, and established not for a perpetuity, but for a single year. Hence, we must still adhere steadily to what was asserted at the commencement, that kings were at first constituted for the maintenance of justice and equity. Had they been able to abide inviolably by this rule, they might have secured perpetual possession of the sovereignty, such as they had received it, that is, free and unshackled by laws. But, as the state of human affairs has, according to the usual progress of every created existence, a constant tendency to deterioration, regal government, which was originally instituted for the purposes of public utility, degenerated gradually into impotent tyranny. For, when kings observed no laws but their capricious passions, and finding their power uncircumscribed and immoderate, set no bounds to their lusts, and were swayed much by favour, much by hatred, and much by private interest, their domineering [105] insolence excited an universal desire for laws. On this account, statutes were enacted by the people, and kings were, in their judicial decisions, obliged to adopt, not what their own licentious fancies dictated, but what the laws, sanctioned by the people, ordained. For they had been taught, by many experiments, that it was much safer to trust their liberties to laws than to kings; since many causes might induce the latter to deviate from rectitude; and the former, being equally deaf to prayers and to threats, always maintained an even and invariable tenor. Kings being accordingly left, in other respects, free, found their power confined to prescribed limits only by the necessity of squaring their words and actions by the directions of law, and by inflicting punishments and bestowing rewards, the two strongest ties of human society, according to its ordinances; so that, in conformity to the expressions of a distinguished adept in political science, a king became a speaking law, and law a dumb king.

M. At the first outset of your discourse, you were so lavish in praise of kings, that the veneration due to their august majesty seemed to render them almost sacred and inviolable. But now, as if actuated by repentance, you confine them to narrow bounds, and thrust them, as it were, into the cells of law, so as not to leave them even the common freedoms of speech. Me you have egregiously disappointed; for I was in great hopes that, in the progress of your discourse, you would, either of your own accord or at my suggestion, restore what an illustrious historian calls the most glorious spectacle in the eyes of gods and men to its original splendour; but, by spoiling of every ornament, and circumscribing within a close prison the magistracy first known in the world, you have so [106] debased it, that to any person in his sober senses it must be an object of contempt rather than of desire. For can there be a man, whose brain is not deranged, that would not choose rather to rest satisfied with a moderate fortune in a private station, than, while he is intent upon other men’s business and inattentive to his own, to be obliged, in the midst of perpetual vexations, to regulate the whole course of his life by the caprice of the multitude? Hence, if it be proposed that this should everywhere be the condition of royalty, I fear that there will soon be a greater scarcity of kings than in the first infancy of our religion there was of bishops. Indeed, if this be the criterion by which we are to estimate kings, I am not surprised that the persons who formerly accepted of such an illustrious dignity, were found only among shepherds and ploughmen.

B. Mark, I beseech you, the egregious mistake which you commit, in supposing that nations created kings not for the maintenance of justice, but for the enjoyment of pleasure. Consider how much, by this plan, you retrench and narrow their greatness. And, that you may the more easily comprehend what I mean, compare any of the kings whom you have seen, and whose resemblance you wish to find in the king that I describe, when he appears at his levee dressed, for idle show, like a girl’s doll, in all the colours of the rainbow, and surrounded with vast parade by an immense crowd; compare, I say, any of these with the renowned princes of antiquity, whose memory still lives and flourishes, and will be celebrated among the latest posterity, and you will perceive that they were the originals of the picture that I have just sketched. Have you never heard in conversation, that Philip of Macedon, upon answering an old woman that [107] begged of him to inquire into a grievance of which she complained, “That he was not at leisure,” and upon receiving this reply, “Cease, then, to be a king;” —have you heard, I say, that this king, the conqueror of so many states, and the lord of so many nations, when reminded of his functions by a poor old woman, complied and recognised the official duty of a king? Compare this Philip, then, not only with the greatest kings that now exist in Europe, but also with the most renowned in ancient story, and you will find none his match in prudence, fortitude, and patience of labour, and few his equals in extent of dominion. Leonidas, Agesilaus, and other Spartan kings, all great men, I forbear to mention, lest I should be thought to produce obsolete examples. One saying, however, of Gorgo, a Spartan maid, and the daughter of king Cleomedes, I cannot pass unnoticed. Seeing his slave pulling off the slippers of an Asiatic guest, she exclaimed, in running up to her father, “Father, your guest has no hands.” From these expressions, you may easily form an estimate of the whole discipline of Sparta, and of the domestic economy of its kings. Yet, to this rustic, but manly, discipline, we owe our present acquisitions, such as they are; while the Asiatic school has only furnished sluggards, by whom the fairest inheritance, the fruit of ancestral virtue, has been lost through luxury and effeminacy. And, without mentioning the ancients, such not long ago among the Gallicians was Pelagius, who gave the first shock to the power of the Saracens in Spain. Though

Beneath one humble roof, their common shade,

His sheep, his shepherds, and his gods were laid;

[108]

yet the Spanish kings are so far from being ashamed of him, that they reckon it their greatest glory to find their branch of the genealogic tree terminate in his trunk. But, as this topic requires a more ample discussion, let us return to the point at which the digression began. For I wish, with all possible speed, to evince what I first promised, that this representation of royalty is not a fiction of my brain, but its express image, as conceived by the most illustrious statesmen in all ages; and, therefore, I shall briefly enumerate the originals from which it has been copied. Marcus Tullius Cicero’s volume concerning moral duties is in universal esteem, and in the second book of it you will find these expressions:—“In my opinion, not only the Medes, as Herodotus says, but also our ancestors, selected men of good morals as kings, for the purpose of enjoying the benefit of justice. For, when the needy multitude happened to be oppressed by the wealthy, they had recourse to some person of eminent merit, who might secure the weak from injury, and, with a steady arm, hold the balance of law even between the high and low. And the same cause, which rendered kings necessary, occasioned the institution of laws. For the constant object of pursuit was uniform justice, since otherwise it would not be justice. When this advantage could be derived from one just and good man, they were satisfied; but, when that was not the case, they enacted laws that should at all times, and to all persons, speak the same language. Hence the deduction is evident, that those were usually selected for supreme magistrates of whose justice the multitude entertained a high opinion; and, if besides they had the additional recommendation of wisdom, there was nothing which they thought themselves [109] incapable of acquiring under their auspices.” From these words you understand, I presume, what, in Cicero’s opinion, induced nations to wish both for kings and for laws. Here I might recommend to your perusal the works of Xenophon, who was no less distinguished for military achievements than for attachment to philosophy, did I not know your familiarity with him to be such that you can repeat almost all his sentences. Of Plato, however, and Aristotle, though I know how much you prize their opinions, I say nothing at present; because I choose rather to have men illustrious for real action, than for their name in the shades of academies, for my auxiliaries. The stoical king, such as he is described by Seneca in his Thyestes, I am still less disposed to offer to your consideration, not so much because he is not a perfect image of a good king, as because that pattern of a good prince is solely an ideal conception of the mind, calculated for admiration rather than a well-grounded hope ever likely to be gratified. Besides, that there might be no room for malevolent insinuations against the examples which I have produced, I have not travelled into the desert of the Scythians for men who either curried their own horses, or performed any other servile work incompatible with our manners, but into the heart of Greece, and for those men who, at the very time when the Greeks were most distinguished for the liberal and polite arts, presided over the greatest nations and the best-regulated communities, and presided over them in such a manner, that, when alive, they acquired the highest veneration among their countrymen, and left, when dead, their memory glorious to posterity.

M. Here, if you should insist upon a declaration of my sentiments, I must say that I dare hardly [110] confess either my inconsistency, or timidity, or other anonymous mental infirmity. For, whenever I read in the most excellent historians, the passages which you have either quoted or indicated, or hear their doctrines commended by sages whose authority I have not the confidence to question, and praised by all good men, they appear to me not only true, just, and sound, but even noble and splendid. Again, when I direct my eye to the elegancies and niceties of our times, the sanctity and sobriety of the ancients seem rather uncouth and destitute of the requisite polish. But this subject we may, perhaps, discuss some other time at our leisure. Now proceed, if you please, to finish the plan which you have begun.

B. Will you allow me, then, to make a brief abstract of what has been said? Thus we shall best gain a simultaneous view of what has passed, and have it in our power to retract any inconsiderate or rash concession.

M. By all means.

B. First of all, then, we ascertained that the human species was, by nature, made for society, and for living in a community?

M. We did so.

B. We also agreed that a king, for being a man of consummate virtue, was chosen as a guardian to the society.

M. That is true.

B. And, as the mutual quarrels of the people had introduced the necessity of creating kings, so the injuries done by kings to their subjects occasioned the desire of laws.

M. I own it.

B. Laws, therefore, we judged a specimen of the regal art, as the precepts of medicine are of the medical art.

[111]

M. We did so.

B. As we could not allow to either a singular and exact knowledge of his art, we judged it safer that each should, in his method of cure, follow the prescribed rules of his art, than act at random.

M. It is safer undoubtedly.

B. But the precepts of the medical art seemed not of one single kind.

M. How?

B. Some we found calculated for preserving, and others for restoring health.

M. The division is just.

B. How is it with the regal art?

M. It contains, I think, as many species.

B. The next point to be considered is, what answer ought to be given to the following question—“Can you think that physicians are so thoroughly acquainted with all diseases and their remedies that nothing farther can be desired for their cure?”

M. By no means. For many new kinds of diseases start up almost every age; and likewise new remedies for each are, almost every year, either discovered by the industry of men or imported from distant regions.

B. What do you think of the civil laws of society?

M. They seem, in their nature, to be similar, if not the same.

B. The written precepts of their arts then will not enable either physicians or kings to prevent or to cure all the diseases of individuals or of communities.

M. I deem the thing impossible.

B. Why, then, should we not investigate as well the articles which can, as those which cannot, come within the purview of laws?

M. Our labour will not be fruitless.

[116]

B. The matters which it is impossible to comprehend within laws seem to me numerous and important; and first of all comes whatever admits of deliberation concerning the future.

M. That is certainly one head of exception.

B. The next is a multitude of past events; such as those where truth is investigated by conjectures, or confirmed by witnesses, or wrung from criminals by tortures.

M. Nothing can be clearer.

B. In elucidating these questions, then, what will be the duty of a king?

M. Here I think that there is no great occasion for long discussion, since, in what regards provision for the future, kings are so far from arrogating supreme power, that they readily invite to their assistance counsel learned in the law.

B. What do you think of matters which are collected from conjectures, or cleared up by witnesses, such as are the crimes of murder, of adultery, and impoisonment?

M. These points, after they have been discussed by the ingenuity, and cleared up by the address of lawyers, I see generally left to the determination of judges.

B. And, perhaps, with propriety; for if the king should take it into his head to hear the causes of individuals, when will he have leisure to think of war, of peace, and of those important affairs which involve the safety and existence of the community? When, in a word, will he have time to recruit nature by doing nothing?

M. The cognisance of every question I do not wish to see devolved upon the king alone; because, if it were devolved, he, a single man, would never be equal to the task of canvassing all the causes of all his subjects. I therefore highly [113] approve the advice no less wise than necessary given to Moses, by his father-in-law, “To divide among numbers the burden of judicature;” upon which I forbear to enlarge, because the story is universally known.

B. But even these judges, I suppose, are to administer justice according to the directions of the laws?

M. They are, undoubtedly. But, from what you have said, I see that there are but few things for which the laws can, in comparison of those for which they cannot, provide.

B. There is another additional difficulty of no less magnitude, that all the cases, for which laws may be enacted, cannot be comprised within any prescribed and determinate form of words.

M. How so?

B. The lawyers, who greatly magnify their art, and would be thought the high-priests of justice, allege, That the multitude of cases is so great, that they may be deemed almost infinite, and that every day there arise in states new crimes, like new kind of ulcers. What is to be done here by the legislator, who must adapt his laws to what is present and past?

M. Not much, if he should not be some divinity dropped from heaven.

B. To these inconveniences add another, and that not a small difficulty, that, from the great mutability of human affairs, hardly any art can furnish precepts that ought to be universally permanent and invariably applicable.

M. Nothing can be truer.

B. The safest plan then seems to be, to entrust a skilful physician with the health of his patient, and a king with the preservation of his people: for [114] the physician, by venturing beyond the rules of his art, will often cure the diseased, either with their consent, or sometimes against their will; and the king will impose a new but still a salutary law upon his subjects, by persuasion, or even by compulsion.

M. I can see no obstacle to prevent him.

B. When both are engaged in these acts, do they not seem each to exert a vigour beyond his own law?

M. To me each appears to adhere to his art. For it was one of our preliminary positions, that it is not precepts that constitute art, but the mental powers employed by the artist in treating the subject-matter of art. At one thing, however, if you really speak from your heart, I am in raptures —that, compelled by a kind of injunction from truth, you restored kings to the dignified rank from which they had been violently degraded.

B. Come not so hastily to a conclusion, for you have not yet heard all. The empire of law is attended with another inconvenience. For the law, like an obstinate and unskilful task-master, thinks nothing right but what itself commands; while a king may perhaps excuse weakness and temerity, and find reason to pardon even detected error. Law is deaf, unfeeling, and inexorable. A youth may allege the slippery ground which he treads, as the cause of his fall, and a woman the infirmity of her sex; one may plead poverty, a second drunkenness, and a third friendship. To all these subterfuges what does the law say? Go, executioner, chain his hands, cover his head, and hang him, when scourged, upon the accursed tree. Now, you cannot be ignorant how dangerous it is, in the midst of so much human frailty, to depend for safety on innocence alone.

[115]

M. What you mention is undoubtedly pregnant with danger.

B. I observe, that, on recollecting these circumstances, certain persons are somewhat alarmed.

M. Somewhat, do you say!

B. Hence, when I carefully revolve in my own mind the preceding positions, I fear that my comparison of a physician and a king may, in this particular, appear to have been improperly introduced.

M. In what particular?

B. In releasing both from all bondage to precepts, and in leaving them the power of curing at their will.

M. What do you find here most offensive?

B. When you have heard me, I shall leave yourself to judge. For the inexpedience of exempting kings from the shackles of laws we assigned two causes, love and hatred, which, in judging, lead the minds of men astray. In the case of a physician, there is no reason to fear that he should act amiss through love, as from restoring the health of his patient he may even expect a reward. And again, if a sick person should suspect that his physician is solicited by prayers, promises, and bribes, to aim at his life, he will be at liberty to call in another; or, if another be not within his reach, he will naturally have recourse for a remedy to dumb books, rather than to a bribed member of the faculty. As to our complaint concerning the inflexible nature of laws, we ought to consider whether it is not chargeable with inconsistency.

M. In what manner?

B. A king of superior excellence, such as is visible rather to the mind than to the eye, we thought proper to subject to no law.

M. To none.

[161]

B. For what reason?

M. Because, I suppose, he would, according to the words of Paul, be a law to himself and to others; as his life would be a just expression of what the law ordains.

B. Your judgment is correct; and, what may perhaps surprise you, some ages before Paul, the same discovery had been made by Aristotle, through the mere light of nature. This remark I make solely for the purpose of showing the more clearly that the voice of God and of nature is the same. But, that we may complete the plan which has been sketched, will you tell me what object the original founders of laws had principally in view?

M. Equity, I presume, as was before observed.

B. What I now inquire is not what end, but rather what pattern, they kept before their eyes.

M. Though, perhaps, I understand your meaning, yet I wish to hear it explained, that, if I am right, you may corroborate my opinion; and, if not, that you may correct my error.

B. You know, I apprehend, the nature of the mind’s power over the body.

M. Some conception of it I can certainly form.

B. You must also know, that of whatever is not thoughtlessly done by men they have previously a certain picture in their mind, and that it is far more perfect than the works which even the greatest artists fashion and express by that model.

M. Of the truth of that observation I have myself, both in speaking and writing, frequently an experimental proof; for I am sensible that my words are no less inadequate to my thoughts than my thoughts to their objects. For neither can our mind, when confined in this dark and turbid prison of the body, clearly discern the subtile essence of all things; nor can we, by language, [117] convey to others our ideas, however preconceived, so as not to be greatly inferior to those formed by our own intellects.

B. What then shall we say was the object of legislators in their institutions?

M. Your meaning, I think myself not far from comprehending; and, if I mistake not, it is that they called to their aid the picture of a perfect king; and by it expressed the figure, not of his person but of his thoughts, and ordered that to be law which he should deem good and equitable.

B. Your conception of the matter is just; for that is the very sentiment which I meant to communicate. Now, I wish that you would consider what were the qualities which we originally gave to our ideal king. Did we not suppose him unmoved by love, by hatred, by anger, by envy, and by the other passions?

M. Such we certainly made his effigy, or even believed him to have actually been in the days of ancient virtue.

B. But do not the laws seem to have been, in some measure, framed according to his image.

M. Nothing is more likely.

B. A good king then will be no less unfeeling and inexorable than a good law.

M. He will be equally relentless; and yet, though I neither can effect, nor ought to desire, a change in either, I may still wish, if it be possible, to render both a little flexible.

B. But in judicial proceedings God does not desire us to pity even the poor, but commands us to look solely to what is right and equitable, and according to that rule alone to pronounce sentence.

M. I acknowledge the soundness of the doctrine, and submit to the force of truth. Since then we must not exempt the king from a dependence on [113] law, who is to be the legislator that we are to give him as an instructor?

B. Whom do you think most fit for the superintendence of this office?

M. If you ask my opinion, I answer, the king himself. For in most other arts the artists themselves deliver the precepts, which serve as memorandums to aid their own recollection, and to remind others of their duty.

B. I, on the contrary, can see no difference between leaving a king free and at large, and granting him the power of enacting laws: as no man will spontaneously put on shackles. Indeed, I know not whether it is not better to leave him quite loose, than to vex him with unavailing chains which he may shake off at pleasure.

B. But, since you trust the helm of state to laws rather than to kings, take care, I beseech you, that you do not subject the person, whom you verbally term king, to a tyrant

With chains and jails his actions to control,

And thwart each liberal purpose of his soul;

and that you do not expose him, when loaded with fetters, to the indignity of toiling with slaves in the field, or with malefactors in the house of correction.

B. Forbear harsh words, I pray; for I subject him to no master, but desire that the people, from whom he derived his power, should have the liberty of prescribing its bounds; and I require that he should exercise over the people only those rights which he has received from their hands. Nor do I wish, as you conceive, to impose these laws upon him by force; but declare it as my opinion, that, after an interchange of counsels with the king, the [119] community should make that a general statute which is conducive to the general good.

M. Would you then assign this province to the people?

B. To the people, undoubtedly, if you should not chance to alter my opinion.

M. Nothing, in my conception, can be more improper.

B. For what reason?

M. You know the proverb, “the people is a monster of many heads.” You are sensible, undoubtedly, of their great rashness and great inconstancy.

B. It was never my idea that this business should be left to the sole decision of all the people; but that, nearly in conformity to our practice, representatives selected from all orders should assemble as council to the king, and that, when they had previously discussed and passed a conditional act, it should be ultimately referred to the people for their sanction.

M. Your plan I perfectly understand; but I think that you gain nothing by your circumspective caution. You do not choose to leave a king above the laws. And, for what? Because there are in human nature two savage monsters, cupidity and irascibility, that wage perpetual war with reason. Laws, therefore, become an object of desire, that they might check their licentiousness, and reclaim their excessive extravagance to a due respect for legal authority. What purpose does it answer to assign him these counsellors selected from the people? Are they not equally the victims of the same intestine war? Do they not suffer as much as kings from the same evils? Therefore, the more assessors you attach to a king, the greater will be [120] the number of fools; and what is to be expected from them is obvious.

B. What you imagine is totally different from the result which I expect; and, why I expect it, I will now unfold. First of all, it is not absolutely true, as you suppose, that there is no advantage in a multitude of counsellors, though none of them, perhaps, should be a man of eminent wisdom. For numbers of men not only see farther, and with more discriminating eyes than any one of them separately, but also than any man that surpasses any single individual among them in understanding and sagacity; for individuals possess certain portions of the virtues, which, being accumulated into one mass, constitute one transcendent virtue. In medical preparations, and particularly in the antidote called mithridatic, this truth is evident; for though most of its ingredients are separately noxious, they afford, when mixed, a sovereign remedy against poisons. After a similar manner, slowness and hesitation prove injurious in some men, as precipitate rashness does in others; but diffused among a multitude, they yield a certain temperament or that golden mean, for which we look in every species of virtue.

M. Well, since you press the matter, let the people have the right of proposing and of enacting laws, and let kings be in some measure only keepers of the records. Yet when these laws shall happen to be contradictory, or to contain clauses indistinctly or obscurely worded, is the king to act no part, especially since, if you insist upon the strict interpretation of them according to the written letter, many absurdities must inevitably ensue? And here, if I produce as an example the hackneyed law of the schools, “If a stranger mount [121] the wall, let him forfeit his head,” what can be more absurd than that a country’s saviour, the man who overturned the enemies on their scaling-ladders, should himself be dragged as a criminal to execution?

M. You approve then of the old saying, “The extremity of law is the extremity of injustice.”

B. I certainly do.

M. If any question of this kind should come into a court of justice, a necessity arises for a merciful interpreter to mitigate the severity of the law, and to prevent what was intended for the general good from proving ruinous to worthy and innocent men.

B. Your sentiments are just; and, if you had been sufficiently attentive, you would have perceived that in the whole of this disquisition I have aimed at nothing else but at preserving sacred and inviolate Cicero’s maxim —“Let the safety of the people be the supreme law.” Therefore, if any case should occur in a court of justice of such a complexion, that there can be no question about what is good and equitable, it will be part of the king’s prospective duty to see the law squared by the fore-mentioned rule. But you seem to me, in the name of kings, to demand more than what the most imperious of them ever arrogate. For you know that, when the law seems to dictate one thing, and its author to have meant another, such questions, as well as controversies grounded upon ambiguous or contradictory laws, are generally referred to the judges. Hence arise the numerous cases solemnly argued by grave counsellors at the bar, and the minute precepts applicable to them in the works of ingenuous rhetoricians.

[122]

M. I know what you assert to be fact. But I think that, in this point, no less injury is done to the laws than to kings. For I judge it better, by the immediate decision of one good man, to end a suit, than to allow ingenious, and sometimes knavish, casuists, the power of obscuring, rather than of explaining the law. For, while the barristers contend not only for the cause of their clients, but also for the glory of ingenuity, discord is in the meantime cherished, religion and irreligion, right and wrong, are confounded; and what we deny to a king, we grant to persons of inferior rank, less studious, in general, of truth than of litigation.

B. You have forgotten, I suspect, a point which we just now ascertained.

M. What may that be?

B. That to the perfect king, whom we at first delineated, such unlimited power ought to be granted, that he can have no occasion for any laws; but that, when this honour is conferred on one of the multitude, not greatly superior, and perhaps even inferior to others, it is dangerous to leave him at large and unfettered by laws.

M. But what is all this to the interpretation of the laws?

B. A great deal; you would find, had you not overlooked a material circumstance, that now we restore in other words to the king, what we had before denied him, the undefined and immoderate power of acting at pleasure, and of unhinging and deranging every thing.

M. If I am guilty of any such thing, it is the guilt of inadvertence.

B. I shall, therefore, endeavour to express my ideas more perspicuously, that there be no misconception. [123] When you grant to the king the interpretation of the law, you allow him the power of making the law speak, not what the legislator intends, or what is for the general good of the community, but what is for the advantage of the interpreter, and, for his own interest, of squaring all proceedings by it, as by an unerring rule. Appius Claudius had, in his decemvirate, enacted a very equitable law, “That in a litigation concerning freedom, the claim of freedom should be favoured.” What language could be clearer? But the very author of this law, by his interpretation, made it useless. You see, I presume, how much you contribute, in one line, to the licentiousness of your king, by enabling him to make the law utter what he wishes, and not utter what he does not wish. If this doctrine be once admitted, it will avail nothing to pass good laws to remind a good king of his duty, and to confine a bad one within due bounds. Nay, (for I will speak my sentiments openly and without disguise,) it would be better to have no laws at all, than, under the cloak of law, to tolerate unrestrained and even honourable robbery.

M. Do you imagine that any king will be so impudent as to pay no regard to his reputation and character among the people, or so forgetful of himself and of his family, as to degenerate into the depravity of those whom he overawes and coerces by ignominy, by prison, by confiscation of goods, and by the heaviest punishments?

B. Let us not believe such events possible, if they are not already historical facts, known by the unspeakable mischiefs which they have occasioned to the whole world.

M. Where, I beseech you, are these facts to be traced?

[124]

B. Where! do you ask? As if all the European nations had not only seen, but also felt, the incalculable mischief done to humanity by, I will not say, the immoderate power, but by the unbridled licentiousness of the Roman pontiff. From what moderate, and apparently honourable, motives it first arose, with what little ground for apprehension it furnished the improvident, none can be ignorant. The laws originally proposed for our direction had not only been derived from the inmost recesses of nature, but also ordained by God, explained by his inspired prophets, confirmed by the Son of God, himself also God, recommended in the writings, and expressed in the lives, and sealed by the blood, of the most approved and sanctified personages. Nor was there, in the whole law, a chapter more carefully penned, more clearly explained, or more strongly enforced, than that which describes the duty of bishops. Hence, as it is an impiety to add, to retrench, to repeal, or alter, a single article in those laws, nothing remained for episcopal ingenuity but the interpretation. The bishop of Rome having assumed this privilege, not only oppressed the other churches, but exercised the most enormous tyranny that ever was seen in the world; for having the audacity to assume authority not only over men, but even over angels, he absolutely degraded Christ; except it be not degradation, that in heaven, on earth and in hell, the Pope’s will should be law; and that Christ’s will should be law only if the Pope pleases. For, if the law should appear rather adverse to his interest, he might, by his interpretation, mould it so as to compel Christ to speak, not only through his mouth, but also according to his mind. Hence, when Christ spoke by the mouth of the Roman pontiff, Pepin [125] seized the crown of Chilperic, and Ferdinand of Arragon dethroned Joan of Navarre; sons took up impious arms against their father, and subjects against their king; and Christ being himself poisoned, was obliged afterwards to become a poisoner, that he might, by poison, destroy Henry of Luxemburg.

M. This is the first time that I ever heard of these enormities. I wish, however, to see what you have advanced concerning the interpretation of laws a little more elucidated.

B. I will produce one single example, from which you may conceive the whole force and tendency of this general argument. “There is a law, that a bishop should be the husband of one wife;” and what can be more plain or less perplexed? But “this one wife the Pope interprets to be one church,” as if the law was ordained for not repressing the lust, but the avarice of bishops. This explanation, however, though nothing at all to the purpose, bearing on its face the specious appearance of piety and decorum, might pass muster, had he not vitiated the whole by a second interpretation. What then does this pontiff contrive? “The interpretation,” says he, “must vary with persons, causes, places, and times.” Such is the distinguished nobility of some men, that no number of churches can be sufficient for their pride. Some churches, again, are so miserably poor, that they cannot afford even to a monk, lately a beggar, now a mitred prelate, an adequate livelihood, if he would maintain the character and dignity of a bishop. By this knavish interpretation of the law there was devised a form, by which those who were called the bishops of single churches held others in commendam, and enjoyed the spoils of [126] all. The day would fail me should I attempt to enumerate the frauds which are daily contrived to evade this single ordinance. But, though these practices are disgraceful to the pontifical name and to the Christian character, the tyranny of the popes did not stop at this limit. For such is the nature of all things, that, when they once begin to slide down the precipice, they never stop till they reach the bottom. Do you wish to have this point elucidated by a splendid example? Do you recollect, among the emperors of Roman blood, any that was either more cruel or more abandoned than Caius Caligula?

M. None that I can remember.

B. Among his enormities which do you think the most infamous action? I do not mean those actions which clerical casuists class among reserved cases, but such as occur in the rest of his life.

M. I cannot recollect.

B. What do you think of his conduct in inviting his horse, called Incitatus, to supper, of laying before him barley of gold, and in naming him consul elect?

M. It was certainly the act of an abandoned wretch.

B. What then is your opinion of his conduct, when he chose him as his colleague in the pontificate?

M. Are you serious in these stories?

B. Serious, undoubtedly; and yet I do not wonder that these facts seem to you fictitious. But our modern Roman Jupiter has acted in such a manner as to justify posterity in deeming these events no longer incredibilities but realities. Here I speak of the pontiff, Julius the third, who [127] seems to me to have entered into a contest for superiority in infamy with that infamous monster, Caius Caligula.

M. What enormity of this kind did he commit?

B. He chose for his colleague in the priesthood his ape’s keeper, a fellow more detestable than that vile beast.

M. There was, perhaps, another reason for his choice.

B. Another is assigned; but I have selected the least dishonourable. Therefore, since not only so great a contempt for the priesthood, but so total a forgetfulness of human dignity, arose from the licentiousness of interpreting the law, I hope that you will no longer reckon that power inconsiderable.