JOHN TRENCHARD AND THOMAS GORDON,

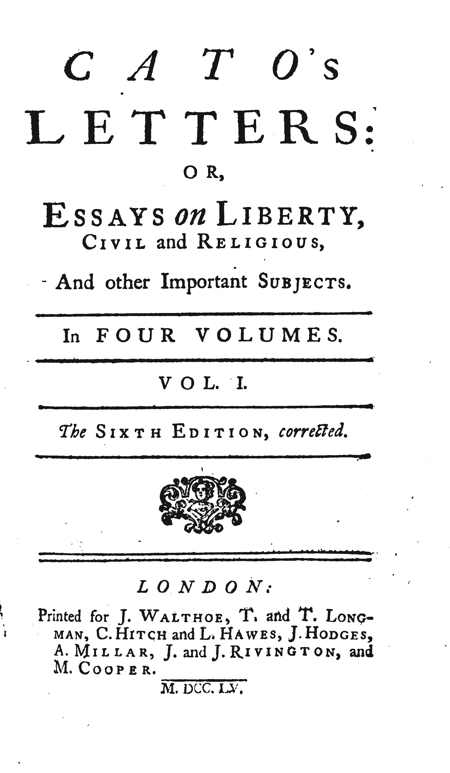

CATO’s LETTERS: or, Essays on Liberty, Civil and Religious, and Other Important Subjects (1720, 6th ed. 1755)

Four volumes in One

|

[Created: 7 May, 2023]

[Updated: June 2, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, Cato’s Letters: or, Essays on Liberty, Civil and Religious, and Other Important Subjects. In Four Volumes. The Sixth Edition, corrected. (London : J. Walthoe, et al. 1755).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1755-CatosLetters/CatosLetters1755-ebook.html

John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, Cato’s Letters: or, Essays on Liberty, Civil and Religious, and Other Important Subjects. In Four Volumes. The Sixth Edition, corrected. (London : Printed for J. Walthoe, T. and T. Longman, C. Hitch and L. Hawes, J. Hodges, A. Millar, J. and J. Rivington, and M. Cooper. MDCCLV (1755)). In four volumes.

- Volume 1: November 5, 1720 to June 17, 1721 - facs. PDF

- Volume 2: June 24, 1721 to March 3, 1722 - facs. PDF

- Volume 3: March 10, 1722 to December 1, 1722 - facs. PDF

- Volume 4: December 8, 1722 to December 7, 1723 - facs. PDF

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

[lxii]

The Contents of the Four Volumes of Cato's Letters

Table of Contents for Volume I.: November 5, 1720 to June 17, 1721

- Dedication to John Milner Esq; of Great Russell-Street Bloomsbury. [Gordon] p. iii

- The Preface [Gordon] p. xii

- No. 1. Saturday, November 5, 1720. Reasons to prove that we are in no Danger of losing Gibraltar. [Gordon] p. 1

- No. 2. Saturday, November 12, 1720. The fatal Effects of the South-Sea Scheme, and the Necessity of punishing the Directors. [Gordon] p. 5

- No. 3. Saturday, November 19, 1720. The pestilent Conduct of the South-Sea Directors, with the reasonable Prospect of publick Justice. [Gordon] p. 10

- No. 4. Saturday, November 26, 1720. Against false Methods of restoring Publick Credit. [Gordon] p. 15

- No. 5. Saturday, December 3, 1720. A further Call for Vengeance upon the South-Sea Plunderers; with a Caution against false Patriots. [Gordon] p. 20

- No. 6. Saturday, December 10, 1720. How easily the People are bubbled by Deceivers. Further Caution against deceitful Remedies for the publick Sufferings from the wicked Execution of the South-Sea Scheme. [Gordon] p. 25

- No. 7. Saturday, December 17, 1720. Further Cautions about new Schemes for publick Redress. [Gordon] p. 30

- No. 8. Saturday, December 24, 1720. The Arts of able guilty Ministers to save themselves. The wise and popular Conduct of Queen Elizabeth towards publick Harpies; with the Application. [Gordon] p, 36

- No. 9. Saturday, December 31, 1720. Against the projected Union of the Three Great Companies; and against remitting to the South-Sea Company any Part of their Debt to the Publick. [Trenchard] p. 42

- No. 10. Tuesday, January 3, 1721. The Iniquity of late and new Projects about the South-Sea considered. How fatally they affect the Publick. (Trenchard and Gordon) p. 51

- No. 11. Saturday, January 7, 1721. The Justice and Necessity of punishing great Crimes, though committed against no subsisting Law of the State. [Gordon] p. 66

- No. 12. Saturday, January 14, 1721. Of Treason: All Treasons not to be found in Statutes. The Right of the Legislature to declare Treasons. [Trenchard] p. 74

- No. 13. Saturday, January 21, 1721. The Arts of misleading the People by Sounds. [Trenchard] p. 83

- No. 14. Saturday, January 28, 1721. The unhappy State of despotick Princes, compared with the happy Lot of such as rule by settled Laws. How the latter, by abusing their Trust, may forfeit their Crown. [Trenchard] p. 88

- No. 15. Saturday, February 4, 1721. Of Freedom of Speech: That the same is inseparable from publick Liberty. [Gordon] p. 96

- No. 16. Saturday, February 11, 1721. The Leaders of Parties, their usual Views. Advice to all Parties to be no longer misled. [Gordon] p. 104

- No. 17. Saturday, February 18, 1721. What Measures are actually taken by wicked and desperate Ministers to ruin and enslave their Country. [Trenchard] p. 111

- No. 18. Saturday, February 25, 1721. The terrible Tendency of publick Corruption to ruin a State, exemplified in that of Rome, and applied to our own. [Trenchard] p. 117

- No. 19. Saturday, March 4, 1721. The Force of popular Affection and Antipathy to particular Men. How powerfully it operates, and how far to be regarded. [Gordon] p. 124

- No. 20. Saturday, March 11, 1721. Of publick Justice, how necessary to the Security and Well-being of a State, and how destructive the Neglect of it to the British Nation. Signal Instances of it. [Trenchard] p. 131

- No. 21. Saturday, March 18, 1721. A Letter from John Ketch, Esq. asserting his Right to the Necks of the over-grown Brokers. [Gordon] p.144

- No. 22. Saturday, March 25, 1721. The Judgment of the People generally sound, where not misled. With the Importance and Probability of bringing over Mr. Knight. (Trenchard and Gordon) p.153

- No. 23. Saturday, April 1, 1721. A memorable Letter from Brutus to Cicero, with an explanatory Introduction. [Gordon] p. 163

- No. 24. Saturday, April 8, 1721. Of the natural Honesty of the People, and their reasonable Demands. How important it is to every Government to consult their Affections and Interest. [Gordon] p. 177

- No. 25. Saturday, April 15, 1721. Considerations on the destructive Spirit of arbitrary Power. With the Blessings of Liberty, and our own Constitution. [Gordon] p. 184

- No. 26. Saturday, April 22, 1721. The sad Effects of general Corruption, quoted from Algernon Sidney, Esq. [Gordon] p. 195

- No. 27. Saturday, April 29, 1721. General Corruption, how ominous to the Publick, and how discouraging to every virtuous Man. With its fatal Progress whenever encouraged. [Gordon] p. 202

- No. 28. Saturday, May 6, 1721. A Defence of Cato against his Defamers. [Gordon]

- TO CATO p. 210

- No. 29. Saturday, May 13, 1721. Reflections occasioned by an Order of Council for suppressing certain impious Clubs that were never discovered. [Gordon] p. 218

- No. 30. Saturday, May 20, 1721. An excellent Letter from Brutus to Atticus; with an explanatory Introduction. [Gordon] p. 227

- No. 31. Saturday, May 27, 1721. Considerations on the Weakness and Inconsistencies of human Nature. [Gordon] p. 237

- No. 32. Saturday, June 10, 1721. Reflections upon Libelling. [Gordon] p. 246

- No. 33. Saturday, June 17, 1721. Cautions against the natural Encroachments of Power. [Gordon] p. 255

- Endnotes to Volume 1

Table of Contents for Volume II.: June 24, 1721 to March 3, 1722

- No. 34. Saturday, June 24, 1721. Of Flattery. [Gordon] p. 3

- No. 35. Saturday, July 1, 1721. Of publick Spirit. [Gordon] p. 11

- No. 36. Saturday, July 8, 1721. Of Loyalty. [Gordon] p. 18

- No. 37. Saturday, July 15, 1721. Character of a good and of an evil Magistrate, quoted from Algernon Sidney, Esq. [Gordon] p. 28

- No. 38. Saturday, July 22, 1721. The Right and Capacity of the People to judge of Government. [Gordon] p. 34

- No. 39. Saturday, July 29, 1721. Of the Passions; that they are all alike good or all alike evil, according as they are applied. [Gordon] p. 43

- No. 40. Saturday, August 5, 1721. Considerations on the restless and selfish Spirit of Man. [Gordon] p. 50

- No. 41. Saturday, August 19, 1721. The Emperor Galba’s Speech to Piso, with an Introduction. [Gordon] p. 56

- No. 42. Saturday, August 26, 1721. Considerations on the Nature of Laws. [Gordon] p. 64

- No. 43. Saturday, September 2, 1721. The natural Passion of Men for Superiority. [Gordon] p. 71

- No. 44. Saturday, September 9, 1721. Men not ruled by Principle, but by Passion. [Gordon] p. 44

- No. 45. Saturday, September 16, 1721. Of the Equality and Inequality of Men. [Gordon] p. 85

- No. 46. Saturday, September 23, 1721. Of the false Guises which Men put on, and their ill Effect. [Gordon] p. 91

- No. 47. Saturday, October 7, 1721. Of the Frailty and Uncertainty of human Judgment. [Gordon] p. 97

- No. 48. Saturday, October 14, 1721. The general unhappy State of the World, ftom the Baseness and Iniquity of its Governors in most Countries. [Gordon] p. 104

- No. 49. Saturday, October 21, 1721. Of the Power of Prejudice. [Gordon] p. 112

- No. 50. Saturday, October 28, 1721. An Idea of the Turkish Government, taken from Sir Paul Ricaut. [Gordon] p. 120

- No. 51. Saturday, November 4, 1721. Popularity no Proof of Merit. [Gordon] p. 128

- No. 52. Saturday, November II, 1721. Of Divine Judgments; the Wickedness and Absurdity of applying them to Men and Events. [Gordon] p. 135

- No. 53. Saturday, November 18, 1721. Dr. Prideaux's Reasoning about the Death of Cambyses, examined; whether the same was a Judgment for his killing the Egyptian God Apis. [Gordon] p. 144

- No. 54. Saturday, November 25, 1721. The Reasoning of Dr. Prideaux about the Fate of Brennus the Gaul, and of his Followers, examined; whether the same was a Judgment for an Intention to plunder the Temple of Delphos. [Gordon] p. 152

- No. 55. Saturday, December 2, 1721. The Lawfulness of killing Julius Caesar considered, and defended, against Dr. Prideaux. [Gordon] p. 165

- No. 56. Saturday, December 9, 1721. A Vindication of Brutus, for having killed Caesar. [Gordon] p. 177

- No. 57. Saturday, December 16, 1721. Of false Honour, publick and private. [Gordon] p. 192

- No. 58. Saturday, December 23, 1721. Letter from a Lady, with an Answer, about Love, Marriage, and Settlements. (A Woman, Trenchard, and Gordon) p. 201

- No. 59. Saturday, December 30, 1721. Liberty proved to be the unalienable Right of all Mankind. [Trenchard] p. 214

- No. 60. Saturday, January 6, 1722. All Government proved to be instituted by Men, and only to intend the general Good of Men. [Trenchard] p. 226

- No. 61. Saturday, January 13, 1722. How free Governments are to be framed so as to last, and how they differ from such as are arbitrary. [Trenchard] p. 236

- No. 62. Saturday, January 20, 1722. An Enquiry into the Nature and Extent of Liberty; with its Loveliness and Advantages, and the vile Effects of Slavery. [Gordon] p. 244

- No. 63. Saturday, January 27, 1722. Civil Liberty produces all Civil Blessings, and how; with the baneful Nature of Tyranny. [Gordon] p. 257

- No. 64. Saturday, February 3, 1722. Trade and Naval Power the Offspring of Civil Liberty only, and cannot subsist without it. [Trenchard] p. 267

- No. 65. Saturday, February 10, 1722. Military Virtue produced and supported by Civil Liberty only. [Gordon] p. 278

- No. 66. Saturday, February 17, 1722. Arbitrary Government proved incompatible with true Religion, whether Natural or Revealed. [Gordon] p. 292

- No. 67. Saturday, February 24, 1722. Arts and Sciences the Effects of Civil Liberty only, and ever destroyed or oppressed by Tyranny. [Gordon] p. 305

- No. 68. Saturday, March 3, 1722. Property and Commerce secure in a free Government only; with the consuming Miseries under simple Monarchies. [Gordon] p. 321

Table of Contents for Volume III.: March 10, 1722 to December 1, 1722

- No. 69. Saturday, March 10, 1722. Address to the Freeholders, &c. about the Choice of their Representatives. [Trenchard] p. 3

- No. 70. Saturday, March 17, 1722. Second Address to the Freeholders, &c. upon the same Subject.[Gordon] p. 12

- No. 71. Saturday, March 31, 1722. Polite Arts and Learning naturally produced in free States, and marred by such as are not free. [Gordon] p. 27

- No. 72. Saturday, April 7, 1722. In absolute Monarchies the Monarch seldom rules, but his Creatures instead of him. That Sort of Government a Gradation of Tyrants. [Gordon] p. 41

- No. 73. Saturday, April 21, 1722. A Display of Tyranny, its destructive Nature, and Tendency to dispeople the Earth. [Gordon] p. 55

- No. 74. Saturday, April 28, 1722. The Vanity of Conquerors, and the Calamities attending Conquests. [Gordon] p. 67

- No. 75. Saturday, May 5, 1722. Of the Restraints which ought to be laid upon publick Rulers. [Gordon] p. 75

- No. 76. Saturday, May 12, 1722. The same Subject continued. [Gordon] p. 84

- No. 77. Saturday, May 19, 1722. Of superstitious Fears, and their Causes natural and accidental. [Trenchard] p. 90

- No. 78. Saturday, May 26, 1722. The common Notion of Spirits, their Power and Feats, exposed. [Trenchard] p. 99

- No. 79. Saturday, June 2, 1722. A further Detection of the vulgar Absurdities about Ghosts and Witches. [Trenchard] p. 108

- No. 80. Saturday, June 9, 1722. That the two great Parties in England do not differ so much as they think in Principles of Politicks. [Trenchard] p. 118

- No. 81. Saturday, June 16, 1722. The Established Church of England in no Danger from Dissenters. [Trenchard] p. 125

- No. 82. Saturday, June 23, 1722. The Folly and Characters of such as would overthrow the present Establishment. [Trenchard] p. 132

- No. 83. Saturday, June 30, 1722. The vain Hopes of the Pretender and his Party. [Trenchard] p. 141

- No. 84. Saturday, July 7, 1722. Property the first Principle of Power. The Errors of our Princes who attended not to this. [Trenchard] p. 150

- No. 85. Saturday, July 14, 1722. Britain incapable of any Government but a limited Monarchy; with the Defects of a neighbouring Republick. [Trenchard] p. 159

- No. 86. Saturday, July 21, 1722. The terrible Consequences of a War to England, and Reasons against engaging in one. [Trenchard] p. 166

- No. 87. Saturday, July 28, 1722. Gold and Silver in a Country to be considered only as Commodities. [Trenchard] p. 176

- No. 88. Saturday, August 4, 1722. The Reasonableness and Advantage of allowing the Exportation of Gold and Silver, with the Impossibility of preventing the same. [Trenchard] p. 184

- No. 89. Saturday, August 11, 1722. Every Man's true Interest found in the general Interest. How little this is considered. [Trenchard] p. 192

- No. 90. Saturday, August 18, 1722. Monopolies and exclusive Companies, how pernicious to Trade. [Trenchard] p. 199

- No. 91. Saturday, August 25, 1722. How exclusive Companies influence and hurt our Government. [Trenchard] p. 206

- No. 92. Saturday, September 1, 1722. Against the Petition of the South-Sea Company, for a Remittance of Two Millions of their Debt to the Publick. [Trenchard] p. 213

- No. 93. Saturday, September 8, 1722. An Essay upon Heroes. [Gordon] p. 224

- No. 94. Saturday, September 15, 1722. Against Standing Armies. (Trenchard and Gordon) p. 234

- No. 95. Saturday, September 22, 1722. Further Reasonings against Standing Armies. [Trenchard] p. 244

- No. 96. Saturday, September 29, 1722. Of Parties in England; how they vary, and interchange Characters, just as they are in Power, or out of it, yet still keep their former Names. [Gordon] p. 258

- No. 97. Saturday, October 6, 1722. How much it is the Interest of Governors to use the Governed well; with an Enquiry into the Causes of Disaffection in England. [Trenchard] p. 266

- No. 98. Saturday, October 13, 1722. Address to the Members of the House of Commons. [Trenchard] p. 275

- No. 99. Saturday, October 20, 1722. The important Duty of Attendance in Parliament, recommended to the Members. [Gordon] p. 283

- No. 100. Saturday, October 27, 1722. Discourse upon Libels. [Trenchard] p. 292

- No. 101. Saturday, November 3, 1722. Second Discourse upon Libels. [Trenchard] p. 300

- No. 102. Saturday, November 10, 1722. The Contemptibleness of Grandeur without Virtue. [Trenchard] p. 307

- No. 103. Saturday, November 17, 1722. Of Eloquence, considered politically. [Trenchard] p. 313

- No. 104. Saturday, November 24, 1722. Of Eloquence, considered philosophically. [Gordon] p. 322

- No. 105. Saturday, December 1, 1722. Of the Weakness of the human Mind; how easily it is misled. [Trenchard] p. 330

- Endnotes to Volume 3

Table of Contents for Volume IV.: December 8, 1722 to December 7, 1723

- No. 106. Saturday, December 8, 1722. Of Plantations and Colonies. [Trenchard] p. 3

- No. 107. Saturday, December 15, 1722. Of publick Credit and Stocks. [Trenchard] p. 12

- No. 108. Saturday, December 22, 1722. Inquiry into the Source of moral Virtues. [Trenchard] p. 24

- No. 109. Saturday, December 29, 1722. Inquiry into the Origin of Good and Evil. [Trenchard] p. 31

- No. 110. Saturday, January 5, 1723. Of Liberty and Necessity. [Trenchard] p. 38

- No. 111. Saturday, January 12, 1723. The same Subject continued. [Trenchard] p. 47

- No. 112. Saturday, January 19, 1723. Fondness for Posterity nothing else but Self-love. Such as are Friends to publick Liberty, are the only true Lovers of Posterity. [Trenchard] p. 58

- No. 113. Saturday, January 26, 1723. Letter to Cato, concerning his many Adversaries and Answerers. [Gordon] p. 65

- No. 114. Saturday, February 2, 1723. The necessary Decay of Popish States shewn from the Nature of the Popish Religion. [Trenchard] p. 73

- No. 115. Saturday, February 9, 1723. The encroaching Nature of Power, ever to be watched and checked. [Trenchard] p. 81

- No. 116. Saturday, February 16, 1723. That whatever moves and acts, does so mechanically and necessarily. [Trenchard] p. 86

- No. 117. Saturday, February 23, 1723. Of the Abuse of Words, applied more particularly to the covetous Man and the Bigot. [Gordon] p. 96

- No. 118. Saturday, March 2, 1723. Free states vindicated from the common Imputation of Ingratitude. [Gordon] p. 104

- No. 119. Saturday, March 9, 1723. The same Subject continued. [Gordon] p. 112

- No. 120. Saturday, March 16, 1723. Of the proper Use of Words. [Trenchard] p. 118

- No. 121. Saturday, March 23, 1723. Of Good Breeding. [Gordon] p. 126

- No. 122. Saturday, March 30, 1723. Inquiry concerning the Operations of the Mind of Man, and those of other Animals. [Trenchard] p. 133

- No. 123. Saturday, April 6, 1723. Inquiry concerning Madness, especially religious Madness, called Enthusiasm. [Gordon] p. 144

- No. 124. Saturday, April 13, 1723. Further Reasonings upon Enthusiasm. [Trenchard] p. 152

- No. 125. Saturday, April 20, 1723. The Spirit of the Conspirators, Accomplices with Dr. Atterbury, in 1723, considered and exposed. [Gordon] p. 163

- No. 126. Saturday, April 27, 1723. Address to those of the Clergy who are fond of the Pretender and his Cause. [Gordon] p. 173

- No. 127. Saturday, May 4, 1723. The same Address continued. [Gordon] p. 181

- No. 128. Saturday, May 11, 1723. Address to such of the Laity as are Followers of the disaffected Clergy, and of their Accomplices. [Trenchard] p. 188

- No. 129. Saturday, May 18, 1723. The same Address continued. [Gordon] p. 197

- No. 130. Saturday, May 25, 1723. The same Address continued. [Trenchard] p. 207

- No. 131. Saturday, June 1, 1723. Of Reverence true and false. [Gordon] p. 216

- No. 132. Saturday, June 8, 1723. Inquiry into the Doctrine of Hereditary Right. [Trenchard] p. 225

- No. 133. Saturday, June 15, 1723. Of Charity, and Charity-Schools. [Trenchard] p. 236

- No. 134. Saturday, June 29, 1723. What small and foolish Causes often misguide and animate the Multitude. [Gordon] p. 247

- No. 135. Saturday, July 6, 1723. Inquiry into the indelible Character claimed by some of the Clergy. [Gordon] p. 254

- No. 136. Saturday, July 13, 1723. The Popish Hierarchy deduced in a great Measure from that of the Pagans. [Trenchard] p. 265

- No. 137. Saturday, July 20, 1723. Of the different and absurd Notions which Men entertain of God. [Trenchard] p. 274

- No. 138. Saturday, July 27, 1723. Cato's Farewell. (Trenchard and Gordon) p. 281

- Endnotes to Volume 4

AN APPENDIX Containing additional letters by Cato (24 August to 7 Decvember 1723

- No. 1. Saturday, August 24, 1723. That ambitious Princes rule and conquer only for their own Sakes; illustrated in a Dialogue between Alexander the Great and a Persian. [Gordon] p. 291

- No. 2. Saturday, September 14, 1723. Considerations upon the Condition of an absolute Prince. [Gordon] p. 299

- No. 3. Saturday, November 2, 1723. The same Subject continued. [Gordon] p. 305

- No. 4. Saturday, November 9, 1723. The same Subject continued. [Trenchard] p. 314

- No. 5. Saturday, November 30, 1723. Considerations upon the Condition of Prime Ministers of State. [Gordon] p. 322

- No. 6. Saturday, December 7, 1723. The same Subject continued. [Gordon] p. 328

CATO'S LETTERS:

or,

ESSAYS on LIBERTY,

Civil and Religious,

And other Important Subjects.

In FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

The Sixth Edition, corrected

DEDICATION TO JOHN MILNER, ESQ; OF GREAT RUSSEL-STREET BLOOMSBURY. [Gordon]↩

[I-iii]

SIR,

As shy as I know you to be of publick notice and eclat, let me for once draw, if not you, your name at least, from that recess which you value in proportion to the measure of felicity that you derive from it, and to your contempt for the blaze and tumult of publick life: A taste to which I have the pleasure of finding my own so entirely conformable.

Quiet passions and an easy mind constitute happiness; which is never found where these are not, and must cease to be, when these cease to support it. Mighty pomp and retinue, glaring equipages, and the attendance of crowds, are signs, indeed burdens, of greatness, rather than proofs of happiness, which I doubt is least felt where these its appearances are mostseen. The principal happiness which they seem to bring, is, that other peoplethink them marks of it; and very imperfect must be that happiness which a man derives not from what he himself feels, but from what another imagines. We may indeed be happy in our own dreams, but can never be happy by the dreams of others.

Happiest of all men, to me, seems the private man; nor can the opinion of ill-judging crowds make him less happy, because they may think others more so. He who can live alone without uneasiness, who can survey his past life with pleasure, who can look back without compunction or shame, forward without fear or rebuke; he, whose every day hath produced some good, at least is passed with innocence; the silent benefactor, the ready and faithful friend; he who is filled with secret delight, because he feels his heart full of benevolence, who finds pleasure in relieving and assisting; the domestic man, perhaps little talked of, perhaps less seen, beloved by his friends, trusted and esteemed by all that know him, often useful to such as know him not, enjoys such high felicity as the wealth of kingdoms and the bounty of kings cannot confer.

Imaginary happiness is a poor amends for the want of real. Nor can a better reason than this be urged against envying any man's grandeur and state, however mighty it be, however easy it appear. A great lot is ever accompanied with many cares; and whoever stands constantly in the eyes of the world, will be apt to feel a constant concern (perhaps even to anxiety) how to become his station and degree, or how to raise it, or how to keep it from sinking. The more he is set to view, the more glaring will be any blot in his character, and the more magnified: Nay, malignant eyes will be seeing blots where there are none; and ’tis certain, that, with all his grandeur, nay by the means and help of his grandeur, it will be always in the power of very little people to mortify him, when he can no ways in return hurt them: And thus the least man may become an overmatch for the greatest.

Men are more upon a level than is generally believed; or rather the advantage is commonly where ’tis least imagined, if we take our estimate where it ought to be taken, from the state and measure of their passions; since from this source their happiness or misery arises. Greatness accompanied with vexations, is worse than an humble state void of anxiety; and he who aims not at an elevated lot, is happier than he, who, having it, fears to lose it.

Happiness is therefore from within just as much as is virtue; and the virtuous man enjoys the most.

If with this goodness of mind he be also a wise man, and a master of his passions; if to good sense he have joined other laudable accomplishments, a competent acquaintance with books, with a thorough knowledge of the world, and of mankind; if he be a benevolent neighbour, a useful member of society, perfectly disinterested, and justly esteemed; if he have served and saved great numbers; if he be daily protecting the innocent, daily watching and restraining the guilty; his happiness must be complete, and all his reflections pleasing.

Who this happy man is, where this amiable character to be found, is what I pretend not to inform you; though I am persuaded that few that know you, will ask that question. My purpose here is, to desire your permission to prefix your name to the following edition of Cato's Letters, as well as to what I have said of Mr. Trenchard. He esteemed you as much as one man could another: You lived in a long course of intimacy with him: I have long lived, to my great advantage and pleasure, in an equal course of intimacy with you. You saw most of these papers before they came out, and many of them were first left to your perusal and judgment. You know in a great measure which were his, which were mine; and no man else whosoever was concerned or consulted. You know what motives produced them; how remote such motives were from views of interest; and that whilst they continuedin full credit with the publick, they were laid down, purely because it wasjudged that the publick, after all its terrible convulsions, was again become calm and safe.

You can vouch, that, as these letters were the work of no faction or cabal, nor calculated for any lucrative or ambitious ends, or to serve the purposes of any party whatsoever, but that they attacked falsehood and dishonesty in all shapes and parties, without temporizing with any, but doing justice to all, even to the weakest and most unfashionable, and maintaining the principles of liberty against the practices of most parties; so they were dropped without any sordid composition, and without any consideration, save that already mentioned. They had treated of most of the subjects important to the world, and meddled with publick measures and publick men only in great instances.

You know that in the character which I have here given of Mr. Trenchard, I have set him no higher than his own great abilities and many virtues set him; that his failings were small, his talents extraordinary, his probity equal; and that he was one of the worthiest, one of the ablest, one of the most useful men, that ever any country was blessed withal.

You know all the writings which he ever produced, and saw most of them before they were published. You know that whatever he wrote was occasional, the effect of present thought, and for immediate use, and that he never laid up writings in store; an undertaking quite opposite to his turn; and all his acquaintanceknew that he could never submit to such a task.

I mention this last particular in justice to him, that he may not be answerable for any work in which he had no share. Because I have been told that some, who knew nothing, or very little of him, perhaps never saw him, have fathered upon him writings which he never wrote; from no kindness to him, but purely because they were not disposed to let me be the author of a work which found such favourable reception from the world, though it was written several years after that worthy man, my friend, was dead. You, who are one of his executors, and saw all his papers, know, as the other executors perfectly do, that he left no writings at all behind him, but two or three loose papers, once intended for Cato's Letters, and afterwards laid aside; which papers of his, with some of mine of the same sort, you have in your hands.

As you have for many years seen whatever I in tended for the publick, you know by what intervals I translated Tacitus, and when it was that I wrote the discourses upon that author, since you perused both as I produced them, and the discourses prefixed to the first volume were not begun till three years after his death; nor those to the second till two years after the former. You can therefore vouch what an absurd falsehood they are guilty of who would ascribe these discourses to him, to whose valuable name I ever have done, I ever shall do, all honour and exact justice. Had he really written and owned that work, ’tis more than probable, that the same slanderers would have attributed it to somebody else.

I should not have once mentioned this ridiculous falsehood, which you and many others know to be a complete one in all its parts, had it not in some measure concerned the publick. Let this detection be the punishment of the little malicious minds who invented it; nor can there be a greater, if they have one honest passion remaining, that of shame or any other, to represent them to themselves in their own miserable colours, lying, envious, and contemptible. It is a lot sufficiently wretched, to be obliged to hate one's self; and to be hardened against just shame and remorse, is almost as bad. Doubtless it were better to have no soul, than to have a lying and malicious one; better not to be, than to be a false and spiteful being.

Unhappily for these undiscerning slanderers, who, whilst they mean me a reproach, make me a compliment, many of the reflections in the discourses upon Tacitus, are illustrated from books that have been written, and from facts that have happened since Mr. Trenchard's death, some of them long since his death.

It may be proper here to mention another mistake which has generally prevailed; that a noble peer of a neighbouring nation, now dead, had a chief, at least a considerable hand in Cato's Letters. Though what I have already said in this address to you abundantly contradicts this mistake; yet, for the satisfaction of the world, and for the sake of truth and justice, I here solemnly aver (and you well know what I aver to be strictly true) that this noble person never wrote a line of those letters, nor contributed a thought towards them, nor knew who wrote them, till all the world knew; nor was ever consulted about them before or after, nor ever saw any of them till they were published, except one by accident.

I am far from mentioning thus much as any reflection upon that able and learned nobleman, who professed a friendship for Mr. Trenchard and myself, and was so fond of these letters, that, from his great partiality in speaking of them, many people inferred them to be his own. I must add, that he sent once or twice, or oftener, some papers to be published under Cato's name; but as they were judged too particular, and not to coincide with Cato’s design, they were not used. He afterwards published some of them in another form. What heightened the report of his being the author of Cato's Letters, was, that there then came forth a public print of his lordship, with a compliment at the bottom to him, as Cato. I have been told, that this was officiously done by Mr. Toland.

My regard for the memory of Mr. Trenchard obliges me to take notice also of some men, who, since his death, have thought fit to have been very intimate with him; though, to my knowledge and yours, he hardly ever conversed with them, and always strove to shun them, such of them especially as he found to be void of veracity.

Let me add, that these letters are still so well received by the publick, that the last edition has been long since sold off and for above three years past it was scarcely possible to find a set of them, unless in publick auctions. I mention this, that the present edition may not seem owing to the frequent quotations made from them in our late party-hostilities. I flatter myself, that, as these papers contain truths and reasons eternally interesting to human society, they will at all times be found seasonable and useful. They have already survived all the clamour and obloquy of party, and indeed are no longer considered as party- writings, but as impartial lessons of liberty and virtue. Nor would it be a small recommendation of them to the world (if the world knew you as well as I know you) that they have ever had your approbation. I am therefore very proud, upon this publick occasion, to declare, that I have long experienced your faithful friendship; and that I am, with very great and very sincere esteem,

SIR,

Your most faithful and

Most humble servant,

T. Gordon

THE PREFACE↩

[I-xxi]

The following letters, first printed weekly, and then most of them gathered into collections from time to time, are now brought all together into four volumes. They were begun in November, 1720, with an honest and humane intention, to call for publick justice upon the wicked managers of the late fatal South-Sea scheme; and probably helped to procure it, as far as it was procured; by raising in a nation, almost sunk in despair, a spirit not to be withstood by the arts and wealth of the powerful criminals. They were afterwards carried on, upon various publick and important subjects, for nigh three years (except a few intermissions, which will appear by the dates) with a very high reputation; which all the methods taken to decry and misrepresent them could not abate.

The pleasing or displeasing of any party were none of the ends of these letters, which, as a proof of their impartiality, have pleased and displeased all parties; nor are any writers proper to do justice to every party, but such as are attached to none. No candid man can defend any party in all particulars; because every party does, in some particulars, things which cannot be defended; and therefore that man who goes blindly in all the steps of his party, and vindicates all their proceedings, cannot vindicate himself. It is the base office of a slave, and he who sustains it breathes improperly English air; that of the Tuilleries or the Divan would suit him better.

The strongest treatise upon the liberty of the press could not so well shew its great importance to civil liberty, as the universal good reception of these papers has done. The freedom with which they are written has been encouraged and applauded even by those who, in other instances, are enemies to all freedom. But all men love liberty for themselves; and whoever contends for slavery, would still preserve himself from the effects of it. Pride and interest sway him, and he is only hard-hearted to all the rest of the world.

The patrons of passive obedience would do well to consider this, or allow others to consider it for them. These gentlemen have never failed upon every occasion to shew effectually, that their patience was nothing increased by their principles; and that they always, very candidly and humanely, excluded themselves from the consequences of their own doctrines. Whatever their speculations have been, their practices have strongly preached, that no man will suffer injustice and violence, when he can help himself.

Let us therefore, without regarding the ridiculous, narrow, and dishonest notions of selfish and inconsistent men, who say and do contradictory things, make general liberty the interest and choice, as it is certainly the right of all mankind; and brand those as enemies to human society, who are enemies to equal and impartial liberty. Whenever such men are friends to truth, they are so from anger or chance, and not for her own sake, or for the sake of society.

I am glad, however, that by reading and approving many of Cato's Letters, they have been brought to read and approve a general condemnation of their own scheme. It is more than ever they did before; and I am not without hopes, that what they have begun in passion, may end in conviction. Cato is happy, if he has been the means of bringing those men to think for themselves, whose character it has been to let other men think for them: A character, which is the highest shame, and the greatest unhappiness, of a rational being. These papers, having fully opened the principles of liberty and power, and rendered them plain to every understanding, may perhaps have their share in preventing, for the time to come, such storms of zeal for nonsense and falsehood, as have thrown the three kingdoms more than once into convulsions. I hope they have largely helped to cure and remove those monstrous notions of government, which have been long instilled by the crafty few into the ignorant many.

It was no matter of wonder that these letters should be ill understood, and maliciously applied, by some, who, having no principles of their own, or vile ones, were apt to wrest Cato's papers and principles to favour their own prejudices and base wishes. But for such as have always professed to entertain the same sentiments of government with Cato, and yet have been offended with his sentiments; as this their offence was neither his fault nor intention, I can only be sorry for their sakes, that the principles which they avowed at all times should displease them at any time. I am willing to believe, that it was not the doctrine, but the application, that disobliged them. Nor was Cato answerable for this; themselves made it, and often made it wrong. All candid and well-bred men (if Cato may be reckoned in the number) abhor all attacks upon the persons and private characters of men, and all little stories invented or revived to blacken them. These are cowardly and barbarous practices; the work and ambition of little and malicious minds: Nor wanted he any such low and contemptible artifices to gain readers. He attended only to general reasonings about publick virtue and corruption, unbiassed by pique or favour to any man. In this upright and impartial pursuit he abused no man’s person; he courted no man’s fortune; he dreaded no man’s resentment.

It was a heavy charge upon Cato, which however wanted not vouchers (if they were in earnest) that he has spoken disrespectfully, nay, insolently, of the King. But this charge has been only asserted. If it were in the least true, I should be the first to own that all the clamour raised against him was just upon him. But the papers vindicate themselves; nor was any prince ever treated with more sincere duty and regard, in any publick or private writings, than his present Majesty has been in these. In point of principle and affection, his Majesty never had a better subject than Cato; and if he have any bad ones, they are not of Cato's making. I know that this nation cannot be preserved, if this establishment be destroyed; and I am still persuaded, that nothing tended more to his Majesty's advantage and popularity, or more to the credit of his administration, or more to the security of the subject, than the pursuing with quick and impartial vengeance those men, who were enemies to all men, and to his Majesty the most dangerous of all his enemies; a blot and a curse to the nation, and the authors of such discontents in some, and of such designs in others, as the worst men wanted, and the best men feared.

In answer to those deep politicians, who have been puzzled to know who were meant by Cicero and Brutus: Intending to deal candidly with them, and to put them out of pain and doubt, I assure them, that Cicero and Brutus were meant; that I know no present characters or story that will fit theirs; that these letters were translated for the service of liberty in general; and that neither reproof nor praise was intended by them to any man living. And if these guessing sages are in perplexity about any other passage in Cato's letters, it is ten to one but the same answer will relieve them. There was nothing in those letters analogous to our affairs; but as they are extremely fine, full of virtue and good sense, and the love of mankind, it was thought worth while to put them into English, as a proper entertainment for English readers. This was the utmost and only view; and it was at least an unkind mistake to suppose any other.

In one of Brutus's letters it is said, “We do not dispute about the qualifications of a master; we will have no master.” This is far from being stronger than the original: Nisi forte non de serveitute, sed de conditione serviendi, recusandum est a nobis. From whence some have inferred, that because Brutus was against having a master, therefore Cato was against having a king: A strange construction, and a wild consequence! As if the translator of Brutus's letters were not to follow the sense of Brutus: Or, as if there were no difference in England between a king and a master, which are just as opposite as king and tyrant. In a neighbouring country, indeed, they say that their monarch is born master of the kingdom; and I believe they feel it; as they do with a witness in Turkey. But it is not so here: I hope it never will be. We have a king made and limited by the law. Brutus having killed one usurper, was opposing another, overturning by violence all law: Where is the parity, or room for it?

The same defence is to be made for the papers that assert the lawfulness of killing Caesar. It has been a question long debated in the world; though I think it admits of little room for debate; the only arguments to be answered being prejudice and clamour, which are fully answered and exposed in these papers. What is said in them can be only applicable to those who do as Caesar and Brutus did; and can no otherwise affect our free and legal government, than by furnishing real arguments to defend it. The same principle of nature and reason that supported liberty at Rome, must support it here and every where, however the circumstances of adjusting them may vary in different places; as the foundations of tyranny are in all countries, and at all times, essentially the same; namely, too much force in the hands of one man, or of a few unaccountable magistrates, and power without a balance: A sorrowful circumstance for any people to fall into. I hope it is no crime to write against so great an evil. The sum of the question is, whether mankind have a right to be happy, and to oppose their own destruction? And whether any man has a right to make them miserable?

Machiavel puts Caesar upon the same foot with the worst and most detestable tyrants, such as Nabis, Phalaris, and Dionysius. “Nor let any man,” says he,

deceive himself with Caesar's reputation, by finding him so exceedingly eminent in history. Those who cried him up, were either corrupted by his fortune, or terrified by his power; for whilst his empire continued, it was never permitted to any man to say any thing against him. Doubtless if writers had had their liberty, they could have said as much of him as of Catiline: And Caesar is much the worst of the two, by how much it is worse to perpetrate a wicked thing, than to design it. And this may be judged by what is said of Brutus his adversary; for, not daring to speak in plain terms of Caesar, by reason of his power, they, by a kind of reverse, magnified his enemy.

He afterwards gives a summary of the doleful waste and crying miseries brought upon Rome and upon mankind by the imperial wolves his successors; and adds, that, by such a recapitulation, “it will appear what mighty obligations Rome and Italy, and the whole world, had to Caesar.”

I shall say no more of these papers either in general or particular. I leave the several arguments maintained in them to justify themselves, and cannot help thinking that they are supported by the united force of experience, reason, and nature, it is the interest of mankind that they assert; and it is the interest of mankind that they should be true. The opinion of the world concerning them may be known from hence; that they have had more friends and readers at home and abroad than any paper that ever appeared in it; nor does it lessen their praise, that they have also had more enemies.

Who were the authors of these letters, is now, I believe, pretty well known. It is with the utmost sorrow I say, that one of them is lately dead, and his death is a loss to mankind. To me it is by far the greatest and most shocking that I ever knew; as he was the best friend that I ever had; I may say the first friend. I found great credit and advantage in his friendship, and shall value myself upon it as long as I live. From the moment he knew me, ’till the moment he died, every part of his behaviour to me was a proof of his affection for me. From a perfect stranger to him, and without any other recommendation than a casual coffee-house acquaintance, and his own good opinion, he took me into his favour and care, and into as high a degree of intimacy as ever was shewn by one man to another. This was the more remarkable, and did me the greater honour, for that he was naturally as shy in making friendships, as he was eminently constant to those which he had already made. His shyness this way was founded upon wise and virtuous considerations. He knew that in a number of friendships, some would prove superficial, some deceitful, some would be neglected; and he never professed a friendship without a sincere intention to be a friend; which he was satisfied a private man could not be to many at once, in cases of exigency and trial. Besides, he had found much baseness from false friends, who, for his best offices, made him vile returns. He considered mutual friends as under mutual obligations, and he would contract no obligation which he was not in earnest to discharge.

This was agreeable to the great sincerity of his soul, which would suffer him to mislead no man into hopes and expectations without grounds. He would let no body depend upon him in vain. The contrary conduct he thought had great cruelty in it, as it was founding confidence upon deceit, and abusing the good faith of those who trusted in us: Hence hypocrisy on one side, as soon as it was discovered, begot hatred on the other, and false friendship ended in sincere enmity: A violence was done to a tender point of morality, and the reputation of him who did it lost and exposed amongst those who thought that he had the most.

He was indeed so tender and exact in his dealings with all sorts of men, that he used to lay his meaning and purposes minutely before them, and scorned to gain any advantage from their mistaking his intentions. He told them what he would and would not do on his part, and what he expected on theirs, with the utmost accuracy and openness. They at least knew the worst; and the only latitude which he reserved to himself was, to be better than his word; but he would let no man hope for what he did not mean. He thought that he never could be too plain with those whom he had to do with; and as men are apt to construe things most in their own favour, he used to foresee and obviate those their partial constructions, and to fix every thing upon full and express terms. He abhorred the misleading of men by artful and equivocal words; and because people are ready to put meanings upon a man’s countenance and demeanor, his sincerity extended even to his carriage and manner; and though he was very civil to every body, he ordered it so, that the forms of his civility appeared to mean no more than forms, and could not be mistaken for marks of affection, where he had none: And it is very true, that a man's behaviour may, without one word said, make professions and promises, and he may play the knave by a kind look.

He used to say, and from knowing him long and intimately I could believe him when he said, that he never broke a promise nor an appointment in his life, in any instance where it was practicable to keep them. If he were to make a visit at an hour, or to meet a friend at an hour, he was always there before the hour. He observed the same severe punctuality in every other engagement of his, and had a very ill opinion of such as did not make every promise of every kind a matter of morality and honour. He considered a man's behaviour in smaller matters, as a specimen of what he would do in matters that were greater; and that a principle of faithfulness, or the want of it, would shew itself in little as well as in considerable things; that he who would try your patience in the business of an appointment, would fail you in a business of property; that one who promised at random, and misled you without an intention to mislead you, was a trifling man, and wanted honesty, though he had no treachery, as he who did it with design was a knave; that from what cause soever they deceived you, the deceit was the same, and both were equally to be distrusted; that punctuality or remissness, sincerity or perfidiousness, runs, generally, through the whole of a man's life and actions, and you need only observe his behaviour in one or two, to know his behaviour in all; and a negligent man when he is neglected, has no reason to complain, no more than a false man when he is hated. In many instances, negligence has all the effects of falsehood, and is as far from virtue, though not so near vice.

As Mr. Trenchard was wary and reserved in the choice of his friends, so no small faults, no sudden prejudices nor gusts of humour or passion, could shake their interest in him, or induce him to part with them; nor could any calumnies, however artful, nor the most malicious tales and infusions, however speciously dressed up, lessen his regard for them. In those cases, as in all others, he would see with his own eyes, and have full proof, before he believed or condemned. He knew how easily prejudices and stories are taken up; he knew how apt malice and emulation are to creep into the heart of man, and to canker it; how quickly reports are framed, how suddenly improved; how easily an additional word or circumstance can transform good into evil, and evil into good; and how common it is to add words and circumstances, as well as to create facts. He was aware that too many men are governed by ill nature; that the best are liable to prepossessions and misinformation; and that if we listen to every spiteful tale and insinuation that men are prone to utter concerning one another, no two men in the world could be two days' friends. He therefore always judged for himself, unbiassed by passion or any man's authority; and when he did change, it was demonstration that changed him. He carried his tenderness even to his lowest servants; nor could his steward, who had served him many years, and given him long proof of great integrity and good understanding, ever determine him to turn away a servant, till he had satisfied himself that he ought to be turned away. He was not assured but his steward might be prejudiced, notwithstanding his probity: And the steward has told me, that he never went with any complaint to his master, how necessary soever for him to hear, but he went with some uneasiness and diffidence.

No man ever made greater allowances for human infirmities, and for the errors and follies of men. This was a character which he did not bear; but it is religiously true. He knew what feeble materials human nature was made of; perhaps no man that ever was born knew it better. Mankind lay as it were dissected before him, and he saw all their advantages and deformities, all their weaknesses, passions, defects, and excesses, with prodigious clearness, and could describe them with prodigious force. Man in society, man out of society, was perfectly known and familiar to his great and lively understanding, and stood naked to his eye, divested of all the advantages, supplements, and disguises of art. His reasonings upon this subject, as upon all others, were admirable, beautiful, and full of life.

As to his indulgence to human infirmities, he knew that without it every man would be an unsociable creature to another, since every man living has infirmities; that we must take men as they are, or not at all; that it is but mutual equity to allow others what we want and expect to ourselves; that as good and ill qualities are often blended together, so they often arise out of one another: Thus men of great wit and spirit are often men of strong passion and vehemence; and the first makes amends for the last: Thus great humourists are generally very honest men; and weak men have sometimes great good nature. Upon this foundation no man lived more easy and debonair with his acquaintance, or bore their failings better. Good nature and sincerity was all that he expected of them. But in the number of natural infirmities, he never reckoned falsehood and knavery, to which he gave no quarter. Human weaknesses were invincible; but no man was born a knave: He chooses his own character, and no sincere man can love him.

In his transactions with men, he had a surprising talent at bringing them over to his opinion. His first care was that it was sure, and well-grounded, and important; and then he was a prevailing advocate: He entered into it with all his might; and his might was irresistible. He saw it in its whole extent, with all the reasons and all the difficulties, and could throw both into a thousand surprising lights; and nothing could escape him. This a friend of his used to call bringing heaven and earth into his argument. He had indeed a vast variety of images, a deluge of language, mighty persuasion in his looks, and great natural authority. You saw that he was in earnest; you saw his excellent judgment, and you saw his upright soul.

He had the same facility in exposing and taking to pieces plausible and deceitful reasonings. This he did with vast quickness and brevity, and with happy turns of ridicule. Many a grave argument, delivered very plausibly and at large, in good and well-sounding language, he has quite defeated with a sensible jest of three words, or a pleasant story not much longer. He had a promptness at repartee, which few men ever equalled, and none ever excelled. He saw, with great suddenness, the strength and weakness of things, their justness or ridicule, and had equal excellence in shewing either.

The quickness of his spirit made him sometimes say things which were ill taken, and for which, upon recollection, he himself was always sorry. But in the midst of his greatest heat I never heard him utter a word that was shocking or dangerous: So great was his judgment, and the guard which he kept over himself and over the natural impetuosity of his temper. He was naturally a warm man; but his wisdom and observation gave him great wariness and circumspection in great affairs; and never was man more for moderate and calm counsels, or more an enemy to rash ones. He had so little of revenge in his temper, that his personal resentment never carried him to hurt any man, or to wish him hurt, unless from other causes he deserved it.

He had an immense fund of natural eloquence, a graceful and persuasive manner, a world of action, and a style strong, clear, figurative, and full of fire. He attended to sense much more than to the expression; and yet his expression was noble. Coming late into the House of Commons, and being but one session there, he could not exert his great talent that way with freedom; but the few speeches which he made were full of excellent strong sense; and he was always heard with much attention and respect. Whether he would have ever come to have spoke there with perfect ease and boldness, time, from which he is now taken away, could only shew. It is certain, in that short space he acquired very high esteem with all sorts of men, and removed many prejudices conceived against him, before he shewed himself in publick. He had been thought a morose and impracticable man, an imputation which nothing but ill-will, or ignorance of his true character, could lay upon him. He was one of the gayest, pleasantest men that ever lived; an enchanting companion, and full of mirth and raillery; familiar and communicative to the last degree; easy, kind-hearted, and utterly free from all grimace and stateliness. He was accessible to all men. No man came more frankly into conviction; no man was more candid in owning his mistakes; no man more ready to do kind and obliging offices. He had not one ambitious thought, nor a crooked one, nor an envious one. He had but one view; to be in the right, and to do good; and he would have heartily joined with any man, or any party of men, to have attained it. If he erred, he erred innocently; for he sincerely walked according to the best light that he had. Is this the character, this the behaviour, of a morose, of an impracticable man? Yet this was the character of Mr. Trenchard, as many great and worthy men, who once believed the contrary, lived to see.

He was cordially in the interest of mankind, and of this nation, and of this government; and never found fault with publick measures, but when he really thought that they were against the publick. According to the views which he had of things, he judged excellently; and often traced attempts and events to their first true sources, however disguised or denied, by the mere force of his own strong understanding. He had an amazing sagacity and compass of thinking; and it was scarce possible to impose appearances upon him for principles: And they who having the same good affections with him, yet sometimes differed in opinion from him, did it often from the difference of their understandings. They saw not so far into the causes and consequences of things: Few men upon earth did; very few. His active and inquisitive mind, full of velocity and penetration, had not the same limits with those of other men: It was all lightning, and dissipated in an instant the doubts and darkness which bewildered the heads of others. In a moment he unravelled the obscurest questions; in a moment he saw the tendency of things. I could give many undeniable instances, where every jot of the events which he foretold came to pass, and in the manner that he foretold. Without doubt, he was sometimes mistaken; but his mistakes did him no discredit; they arose from no defect in his judgment, and from no sourness of mind.

As he wanted nothing but to see the publick prosper, he emulated no man's greatness; but rejoiced in the publick welfare, whatever hands conducted it. No man ever dreaded publick evils more, or took them more to heart: At one time they had almost broke it. The national confusions, distresses, and despair, which we laboured under a few years ago gave him much anxiety and sorrow, which preyed upon him, and endangered his life so much, that had he staid in town a few days longer, it was more than probable he would never have gone out of it alive. He even dreaded a revolution; and the more, because he saw some easy and secure, who ought to have dreaded it most. This was no riddle to him then, and he fancied that he had lived to see the riddle explained to others.

The personal resentment which he bore to a great man now dead, for personal injuries, had no share in the opposition which he gave to his administration, how natural soever it was to believe that it had. He only considered the publick in that opposition; which he would have gladly dropped, and changed opposition into assistance, without any advantage or regard to himself, if he could have been satisfied that that great man loved his country as well as he loved power. Nor did he ever quarrel with any great man about small considerations. On the contrary, he made great allowances for their errors, for the care of their fortunes and families, and even for their ambition, provided their ambition was honestly directed, and the publick was not degraded or neglected, to satiate their domestick pride. He did not vainly expect from men that perfection and heroism which, he knew, were not to be found in men; and he cared not how much good ministers did to themselves, if by it they hurt not their country. He had two things much at heart; the keeping England out of foreign broils, and paying off the publick debts. He thought that the one depended upon the other, and that the fate and being of the nation depended upon the last; and I believe that few men who think at all, think him mistaken. For a good while before he died he was easier, as to those matters, than I had ever known him. He was pleased with the calm that we were in, and entertained favourable hopes and opinions. Nor is it any discredit to the present administration, that Mr. Trenchard was more partial to it than I ever knew him to any other. In this he sincerely followed his judgment; for it is most certain than he had not one view to himself; nor could any human consideration have withdrawn him from the publick interest. It was hard to mislead him; impossible to corrupt him.

No man was ever more remote from all thoughts of publick employments: He was even determined against them; yet he would never absolutely declare that he would at no time engage in them, because it was barely possible that he might. So nice and severe was his veracity! He had infinite talents for business; a head wonderfully turned for schemes, trains of reasoning, and variety of affairs; extreme promptness, indefatigable industry, a strong memory, mighty dispatch, and great adroitness in applying to the passions of men. This last talent was not generally known to be his: He was thought a positive, uncomplying man; and in matters of right and wrong he was so. But it is as true, that he knew perfectly how mankind were to be dealt with; that he could manage their tempers with great art, and bear with all their humours and weaknesses with great patience. He could reason or rally, be grave or pleasant, with equal success; and make himself extremely agreeable to all sorts of people, without the least departure from his native candour and integrity. As he chiefly loved privacy and a domestick life, he seldom threw himself in the way of popularity; but where-ever he sought it, he had it. One proof of this may be learned from the great town [∗] where he was chosen into Parliament; no man was ever more beloved and admired by any place. He found them full of prejudices against him, and left them full of affection for him. Very different kinds of men, widely different in principle, agreed in loving him equally; and adore his memory, now he is gone. The few sour men who opposed him there, owed him better things, and themselves no credit by their opposition.

In conversation he was frank, cheerful and familiar, without reserve; and entertaining beyond belief. His head was so clear, ready, and so full of knowledge, that I have often heard him make as strong, fine, and useful discourses at his table, as ever he wrote in his closet; though I think he is in the highest class of writers that have appeared in the world. He had such surprizing images, such a happy way of conceiving things, and of putting words together, as few men upon earth ever had. He talked without the pedantry of a man who loves to hear himself talk, or is fond of applause. He was always excellent company; but the time of the day when he shined most, was for three hours or more after dinner: Towards the evening he was generally subject to indigestions. The time which he chose to think in, was the morning.

He was acceptable company to women. He treated them with great niceness and respect; he abounded in their own chit-chat, and said a world of pleasant things. He was a tender and obliging husband; and indeed had uncommon cause to be so, as he well knew, and has shewn by his will: But he had worthy and generous notions of the kind regard which men owe to women in general, especially to their wives; who, when they are bad, may often thank their husbands. This was a theme that he often enlarged upon with great wisdom. He was very partial to the fair sex, and had a great deal of gallantry in his temper.

He was a friendly neighbour: he studied to live well with every body about him; and took a sensible pleasure in doing good offices. He was an enemy to litigiousness and strife; and, I think, he told me, that he never had a law-suit in his life. He was a kind and generous landlord; he never hurried nor distressed any of his tenants for rent, and made them frequent, and unasked, abatements. There were yearly instances of this. He was exact in performing all his covenants with them, and never forgot any promise that he had made them. Nor did he ever deny any tenant any reasonable favour: But he knew his estate well; they could not easily deceive him: And none but such as did so, or attempted it, were known to complain.

To his servants he was a just and merciful master. Under him they had good usage and plenty; and the worst that they had to apprehend in his service, was now and then a passionate expression. He loved to see cheerful faces about him. He was particularly tender of them in their sickness, and often paid large bills for their cure. For this his compassion and bounty he had almost always ill returns. They thought that every kindness done them, was done for their own sake; that they were of such importance to him, that he could not live without them; and that therefore they were entitled to more wages. He used to observe, that this ingratitude was inseparable from inferior servants, and that they always founded some fresh claim upon every kindness which he did them. From hence he was wont to make many fine observations upon human nature, and particularly upon the nature of the common herd of mankind.

Mr. Trenchard had a liberal education, and was bred to the law; in which, as I have heard some of his contemporaries say, he had made amazing progress. But politicks and the Irish Trust, [∗] in which he made a great figure, though very young, took him from the Bar; whither he never had any inclination to return. By the death of an uncle, and his marriage, he was fallen into an easy fortune, with the prospect of a much greater.

He was very knowing, but not learned; that is, he had not read many books. Few books pleased him: Where the matter was not strong, and fine, and laid close together, it could not engage his attention: He out-ran his author, and had much more himself to say upon the subject. He said, that most books were but title pages, and in the first leaf you saw all; that of many books which were valued, half might be thrown away without losing any thing. He knew well the general history and state of the world, and its geography every where. For a gentleman, he was a good mathematician; he had clear and extensive ideas of the astronomical system, of the power of matter and motion, and of the causes and production of things. He understood perfectly the interest of England in all its branches, and the interest and pretensions of the several great powers in Europe, with the state and general balance of trade every where. Upon these subjects, and upon all others that are of use to mankind, he could discourse with marvellous force and pertinency. Perhaps no man living had thought so much and so variously. He had a busy and a just head, and was master of any subject in an instant. He chiefly studied matters that were of importance to the world; but loved poetry, and things of amusement, when the thoughts were just and witty: And no body enjoyed pleasantries more. He had formerly read the classicks, and always retained many of their beautiful passages, particularly from Horace and Lucretius, and from some of the speeches in Lucan. He admired the fire and freedom of the last; as he did Lucretius for the loftiness of his conceptions: And Horace he had almost all by heart. He had the works of Cicero and Tacitus in high esteem: He was not a little pleased when I set about translating the latter. He thought no author so fit to be read by a free people, like this; as none paints with such wisdom and force the shocking deformities of that sort of consuming government, which has rendered almost the whole earth so thin and wretched.

He had a great contempt for logick, and the learning of the Schools; and used to repeat with much mirth an observation of Dr. Smith, late Bishop of Down, his tutor. The doctor used to say, that “Mr. Trenchard's talent of reasoning was owing to his having been so good a logician”; a character for which he was eminent at the university. The truth was, that his reasoning head made him excel in the subtleties of logick. Reason is a faculty not to be learned, no more than wit and penetration. Having as great natural parts as perhaps any man was ever born with, he wanted none of the shew and assistance of art; and many men, who carry about them mighty magazines of learning and quotation, would have made a poor figure in conversation with Mr. Trenchard. He highly valued learned men, when they had good sense, and made good use of their learning: But mere authorities, and terms, and the lumber of words, were sport to him; and he often made good sport of those who excelled in them. He had endless resources in his own strong and ready understanding, and used to strip such men of their armour of names and distinctions with wonderful liveliness and pleasantry. Having lost all the tackle of their art, they had no aids from nature. False learning, false gravity, and false argument, never encountered a more successful foe. Extraordinary learning and extraordinary wit seldom meet in one man: The velocity of their genius renders men of great wit incapable of that laborious patience necessary to make a man very learned. Cicero and Monsieur Bayle, had both, and so had our Milton and George Buchanan. I could name others; but all that I could mention are only exceptions from a general rule. As to Mr. Trenchard, the character of Aper, the Roman orator, suits him so much, that it seems made for him.

Aprum ingenio potius & vi naturae quam institutione & literis famam eloquentiae consecutum—communi eruditione imbutus, contemnebat potius literas quam nesciebat: Ingenium ejus nullis alienarum artium inniti videretur. Dialog. de Oratoribus.

He was not fond of writing; his fault lay far on the other side. He only did it when he thought it necessary. Even in the course of the following letters, he was sometimes several months together without writing one; though, upon the whole, he wrote as many, within about thirty, as I did. He wrote many such as I could not write, and I many such as he would not. But in this edition, to satisfy the curiosity of the publick, I have marked his and my own with the initial letters of our different names at the end of each paper. To him it was owing, to his conversation and strong way of thinking, and to the protection and instruction which he gave me, that I was capable of writing so many. He was the best tutor that I ever had, and to him I owed more than to the whole world besides. I will add, with the same truth, that, but for me, he never would have engaged in any weekly performance whatsoever. From any third hand there was no assistance whatever. I wanted none while I had him, and he sought none while he had me.

His notions of God were noble and refined; and if he was obnoxious to bigots, it was for thinking more honourably of the deity, and for exposing their stupid, sour, and narrow imaginations about him. There was more instruction in three extempore sentences of his upon this subject, than in threescore of their studied sermons. He taught you to love God; they only to dread him. He thought the gospel one continued lesson of mercy and peace; they make it a lasting warrant for contention, severity, and rage. He believed that those men, who found pomp and domination in the self-denying example and precepts of Jesus Christ, were either madmen, or worse—not in earnest; that such as were enemies to liberty of conscience, were enemies to human society, which is a frail thing kept together by mutual necessities and mutual indulgences; and that, in order to reduce the world to one opinion, the whole world must be reduced to one man, and all the rest destroyed.

He saw, with just indignation, the mad, chimerical, selfish, and barbarous tenets maintained by many of the clergy, with the mischievous effects and tendency of these tenets: He saw, as every man that has eyes may, that for every advantage which they have in the world, they are beholden to men and societies; and he thought it downright fraud and impudence, to claim as a gift from God, what all mankind knew was the manifest bounty of men, and the policy of states, or extorted from them; that ecclesiastical jurisdiction and revenues could have no other possible original; that it was a contradiction to all truth, to Christianity, and to all civil government, to allow them any other; that the certain effect of detaching the priesthood from the authority of the civil magistrate, was to enslave the civil magistrate, and all men, to the priesthood; and these claims of the clergy to divine right and independency, raised a combustion, a civil schism in the state (the only schism dangerous to society) made the laity the property or the enemies of the clergy, and taught the clergy avowed ingratitude for every bounty, indulgence, privilege, and advantage, which the laity, or any layman, could bestow upon them; since having all from God, they could consider laymen only as intruders, when laymen meddled with celestial rents, and pretended to give them what God had given them. I am apt to think that from this root of spiritual pride proceeds the too common ingratitude of clergymen to their patrons for very good livings. They think it usurpation in laymen to have church benefices in their gift. Hence their known abhorrence of impropriations; and we all know what they mean, when they find so much precipitancy and so many errors in the Reformation. It was a terrible blow to church dominion, and gave the laity some of their own lands again.

Some will say, that these are only a number of hot-headed men amongst the clergy; and I say, that I mean no other: I only wish that the cool heads may be the majority. That there are many such, I know and congratulate; and I honour with all my heart the many bishops and doctors, who are satisfied with the condition of the clergy, and are friends to conscience and civil liberty; for both which some of them have contended with immortal success.

But whatever offence the high claimers of spiritual dominion gave Mr. Trenchard, he was sincerely for preserving the Established Church, and would have heartily opposed any attempt to alter it. He was against all levelling in church and state, and fearful of trying experiments upon the constitution. He thought that it was already upon a very good balance; and no man was more falsely accused of an intention to pull it down. The establishment was his standard; and he was only for pulling down those who would soar above it, and trample upon it. If he offended churchmen, while he defended the legal church, the blame was not his. He knew of no authority that they had, but what the laws gave them; nor can they shew any other. The sanctions of a thousand synods, the names and volumes of ten thousand fathers, weigh not one grain in this argument. They are no more rules to us, than the oracles of Delphos, no more than a college of augurs. Acts of Parliament alone constitute and limit our church government, and create our clergy; and upon this article Mr. Trenchard only asserted what they themselves had sworn. Personally he used them with great civility where-ever he met them; and he was for depriving them of no part of their dignities and reversions. As to their speculative opinions, when he meddIed with them, he thought that he might take the same liberty to differ with them, which they took to differ with one another. For this many of them have treated his name very barbarously, to their own discredit. Laymen can sometimes fight, and be friends again. The officers and soldiers of two opposite camps, if they meet out of the way of battle, can be well-bred and humane to each other, and well-pleased together, though they are to destroy one another next day. But, I know not how it happens, clerical heat does not easily cool; it rarely knows moderation or any bounds, but pursues men to their death; and even after death it pursues them, when they are no longer subject to the laws or cognizance of men. It was not more good policy than it was justice in these angry men, to charge Mr. Trenchard with want of religion; as it is owning that a man may be a most virtuous man, and an excellent member of society, without it. But, as nothing is so irreligious as the want of charity; so nothing is more indiscreet.

As passionate as he was for liberty, he was not for a Commonwealth in England. He neither believed it possible, nor wished for it. He thought that we were better as we were, than any practicable change could make us; and seemed to apprehend, that a neighbouring republick was not far from some violent shock. I wish that he may have been mistaken; but the grounds of his opinion were too plausible.