DAVID HUME,

Political Discourses (1752)

|

[Created: 28 March, 2023]

[Updated: March 28, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

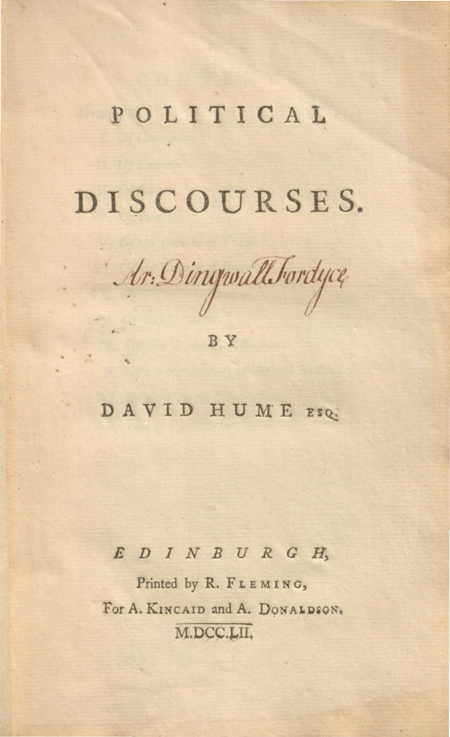

, Political Discourses. By David Hume Esq. (Edinburgh. Printed by R. Fleming, For A. Kincaid and A. Donaldson. M.DCC.LII.(1752)).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1752-Hume_PoliticalDiscourses/Hume_PoliticalDiscourses1752-ebook-enhanced.html

David Hume, Political Discourses. By David Hume Esq. (Edinburgh. Printed by R. Fleming, For A. Kincaid and A. Donaldson. M.DCC.LII.(1752)).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Table of Contents

- DISCOURSE I. Of Commerce. [p. 1]

- DISCOURSE II. Of Luxury. [p. 23]

- DISCOURSE III. Of Money. [p. 41]

- DISCOURSE IV. Of Interest. [p. 61]

- DISCOURSE V. Of the Balance of Trade. [p. 79]

- DISCOURSE VI. Of the Balance of Power. [p. 101]

- DISCOURSE VII. Of Taxes. [p. 115]

- DISCOURSE VIII. Of Public Credit. [p. 123]

- DISCOURSE IX. Of some remarkable customs. [p. 143]

- DISCOURSE X. Of the Populousness of antient Nations. [p. 155]

- DISCOURSE XI. Of the Protestant Succession. [p. 263]

- DISCOURSE XII. Idea of a perfect Commonwealth. [p. 281]

- Endnotes

ERRATA.↩

PAGE 9. line 18. read, He takes the field in his turn; and during his service, is chiefly maintain'd by himself. P. 49. add to the note, And as a recoinage of our silver begins to be requisite by the continual wearing of our shillings and sixpences, 'tis doubtful, whether we ought to imitate the example in king William's reign, when the clipt money was rais'd to the old standard. P. 72. l. 11. r. the price. P. 76. l. 14. for occasion r. accession. P. 89. l. 7. r. the entry of those wines of Languedoc, Guienne and other Southern provinces. P. 183. l. 11. r. of the government. P. 267. l. 3. for their r. the. P. 274. l. 6. r. exclude all high claims like those of their father and grandfather.

[1]

DISCOURSE I.

Of Commerce.↩

THE greatest part of mankind may be divided into two classes; that of shallow thinkers, who fall short of the truth, and that of abstruse thinkers, who go beyond it. The latter class are by far the most uncommon, and I may add, by far the most useful and valuable. They suggest hints, at least, and start difficulties, which they want, perhaps, skill to pursue, but which may produce very fine discoveries, when handled by men who have a more just way of thinking. At worst, what they say is uncommon; and if it should cost some pains to comprehend it, one has, however, the pleasure of hearing something that is new. An author is little to be valu'd, who tells us nothing but what we can learn from every coffee-house conversation.

ALL people of shallow thought are apt to decry even those of solid understanding as abstruse thinkers [2] and metaphysicians and refiners; and never will allow any thing to be just, which is beyond their own weak conceptions. There are some cases, I own, where an extraordinary refinement affords a strong presumption of falshood, and where no reasoning is to be trusted but what is natural and easy. When a man deliberates concerning his conduct in any particular affair, and forms schemes in politics, trade, oeconomy, or any business in life, he never ought to draw his arguments too fine, or connect too long a chain of consequences together. Something is sure to happen, that will disconcert his reasoning, and produce an event different from what he expected. But when we reason upon general subjects, one may justly affirm, that our speculations can scarce ever be too fine, provided they be just; and that the difference betwixt a common man and a man of genius, is chiefly seen in the shallowness or depth of the principles, upon which they proceed. General reasonings seem intricate, merely because they are general; nor is it easy for the bulk of mankind to distinguish, in a great number of particulars, that common circumstance, in which they all agree, or to extract it, pure and unmixt, from the other superfluous circumstances. Every judgment or conclusion, with them, is particular. They cannot enlarge their view to those universal propositions, which comprehend under them an infinite number of individuals, and include a whole [3] science in a single theorem. Their eye is confounded with such an extensive prospect, and the conclusions deriv'd from it, even tho' clearly exprest, seem intricate and obscure. But however intricate they may seem, 'tis certain, that general principles, if just and sound, must always prevail in the general course of things, tho' they may fail in particular cases; and 'tis the chief business of philosophers to regard the general course of things. I may add, that 'tis also the chief business of politicians; especially in the domestic government of the state, where the public good, which is, or ought to be their object, depends on the concurrence of a multitude of cases; not, as in foreign politics, upon accidents, and chances, and the caprices of a few persons. This therefore makes the difference betwixt particular deliberations and general reasonings, and renders subtilty and refinement much more suitable to the latter than to the former.

I THOUGHT this introduction necessary before the following discourses on commerce, luxury, money, interest, &c. where, perhaps, there will occur some principles, which are uncommon, and which may seem too refin'd and subtile for such vulgar subjects. If false, let them be rejected: but no one ought to entertain a prejudice against them, merely because they are out of the common road.

[4]

THE greatness of a state and the happiness of its subjects, however independent they may be suppos'd in some respects, are commonly allow'd to be inseparable with regard to commerce; and as private men receive greater security, in the possession of their trade and riches, from the power of the public, so the public becomes powerful in proportion to the riches and extensive commerce of private men. This maxim is true in general; tho' I cannot forbear thinking, that it may possibly admit of some exceptions, and that we often establish it with too little reserve and limitation. There may be some circumstances, where the commerce and riches and luxury of individuals, instead of adding strength to the public, may serve only to thin its armies, and diminish its authority among the neighbouring nations. Man is a very variable being and susceptible of many different opinions, principles, and rules of conduct. What may be true while he adheres to one way of thinking, will be found false, when he has embrac'd an opposite set of manners and opinions.

THE bulk of every state may be divided into husbandmen and manufacturers. The former are employ'd in the culture of the land. The latter work up the materials furnish'd by the former, into all the commodities, which are necessary or ornamental to human life. As soon as men quit their savage state, where they live chiefly by hunting[5] and fishing, they must fall into these two classes; tho' the arts of agriculture employ at first the most numerous part of the society[*] . Time and experience improve so much these arts, that the land may easily maintain a much greater number of men, than those who are immediately employ'd in its cultivation, or who furnish the more necessary manufactures to such as are so employ'd.

IF these superfluous hands be turn'd towards the finer arts, which are commonly denominated the arts of luxury, they add to the happiness of the state; since they afford to many the opportunity of receiving enjoyments, with which they would otherways have been unacquainted. But may not another scheme be propos'd for the employment of these superfluous hands? May not the sovereign lay claim to them, and employ them in fleets and armies, to increase the dominions of the state abroad, and spread its fame over distant nations? 'Tis certain, that the fewer desires and wants are found in the proprietors and labourers of land, the fewer hands do they employ; and consequently [6] the superfluities of the land, instead of maintaining tradesmen and manufacturers, may support fleets and armies to a much greater extent, than where a great many arts are requir'd to minister to the luxury of particular persons. Here therefore seems to be a kind of opposition betwixt the greatness of the state and the happiness of the subjects. A state is never greater than when all its superfluous hands are employ'd in the service of the public. The ease and convenience of private persons require, that these hands should be employ'd in their service. The one can never be satisfied, but at the expence of the other. As the ambition of the sovereign must entrench on the luxury of individuals; so the luxury of individuals must diminish the force, and check the ambition of the sovereign.

NOR is this reasoning merely chimerical; but is founded on history and experience. The republic of Sparta was certainly more powerful than any state now in the world, consisting of an equal number of people; and this was owing entirely to the want of commerce and luxury. The Helotes were the labourers: The Spartans were the soldiers or gentlemen. 'Tis evident, that the labour of the Helotes could not have maintain'd so great a number of Spartans, had these latter liv'd in ease and delicacy, and given employment to a great variety of trades and manufactures. The like policy may be remark'd in Rome; and indeed, thro' [7] all antient history, 'tis observable, that the smallest republics rais'd and maintain'd greater armies than states, consisting of triple the number of inhabitants, are able to support at present. 'Tis computed that, in all European nations, the proportion betwixt soldiers and people does not exceed one to a hundred. But we read, that the city of Rome alone, with its small territory, rais'd and maintain'd, in early times, ten legions against the Latins. Athens, whose whole dominions were not larger than Yorkshire, sent to the expedition against Sicily near forty thousand men [*] . Dionysius the elder, 'tis said, maintain'd a standing army of a hundred thousand foot and ten thousand horse, beside a large fleet of four hundred sail; [†] tho' his territories extended no farther than the city of Syracuse, about a third part of the island of Sicily, and some sea-port towns or garrisons on the coast of Italy and Illyricum. 'Tis true, the antient armies, in time of war, subsisted much upon plunder: But did not the enemy plunder in their turn? which was a more ruinous way of levying a tax, than any other that could be devis'd. In short, no probable reason can be given for the great power of the more antient states above the modern, but their [8] want of commerce and luxury. Few artizans were maintain'd by the labour of the farmers, and therefore more soldiers might live upon it. Titus Livius says, that Rome, in his time, would find it difficult to raise as large an army as that which, in her early days, she sent out against the Gauls and Latins [*] . Instead of those soldiers who fought for liberty and empire in Camillus's time, there were, in Augustus's days, musicians, painters, cooks, players and taylors. And if the land was equally cultivated at both periods, 'tis evident it could maintain equal numbers in the one profession as in the other. They added nothing to the mere necessaries of life, in the latter period more than in the former.

'TIS natural on this occasion to ask, whether sovereigns may not return to the maxims of antient policy, and consult their own interest, in this respect, more than the happiness of their subjects? I answer, that it appears to me almost impossible; and that because antient policy was violent, and contrary to the more natural and usual course of things. 'Tis well known with what peculiar laws Sparta was govern'd, and what a prodigy that republic is justly esteem'd by every one, who has consider'd human nature, as it has display'd itself in other nations and other ages. Were the testimony [9] of history less positive and circumstantial, such a government wou'd appear a mere philosophical whim or fiction, and impossible ever to be reduc'd to practice. And tho' the Roman and other antient republics were supported on principles somewhat more natural, yet was there a very extraordinary concurrence of circumstances to make them submit to such grievous burthens. They were free states; they were small ones; and the age being martial, all the neighbouring states were continually in arms. Freedom naturally begets public spirit, especially in small states; and this public spirit, this amor patriae, must increase, when the public is almost in continual alarm, and men are oblig'd, every moment, to expose themselves to the greatest dangers for its defence. A continual succession of wars makes every citizen a soldier: They take the field in their turn; and during their service are chiefly maintain'd by themselves. And, notwithstanding that this service is equivalent to a very severe tax, 'tis less felt by a people addicted to arms, who fight for honour and revenge more than pay, and are unacquainted with gain and industry as well as pleasure. [*] Not to mention the [10] great equality of fortunes amongst the inhabitants of the antient republics, where every field, belonging to a different proprietor, was able to maintain a family, and render'd the numbers of citizens very considerable, even without trade and manufactures.

BUT tho' the want of trade and manufactures, amongst a free and very martial people, may sometimes have no other effect than to render the public more powerful; 'tis certain, that, in the common course of human affairs, it will have a quite contrary tendency. Sovereigns must take mankind as they find them, and cannot pretend to introduce any violent change in their principles and ways of thinking. A long course of time, with a variety of accidents and circumstances, are requisite to produce those great revolutions, which so much diversify the face of human affairs. And the less natural any set of principles are, which support a particular society, the more difficulty will a legislator [11] meet with in raising and cultivating them. 'Tis his best policy to comply with the common bent of mankind, and give it all the improvements, of which it is susceptible. Now, according to the most natural course of things, industry and arts and trade increase the power of the sovereign as well as the happiness of the subjects; and that policy is violent, which aggrandizes the public by the poverty of individuals. This will easily appear from a few considerations, which will present to us the consequences of sloth and barbarity.

WHERE manufactures and mechanic arts are not cultivated, the bulk of the people must apply themselves to agriculture; and if their skill and industry increase, there must arise a great superfluity from their labour beyond what suffices to maintain them. They have no temptation, therefore, to increase their skill and industry; since they cannot exchange that superfluity for any commodities, which may serve either to their pleasure or vanity. A habit of indolence naturally prevails. The greater part of the land lyes uncultivated. What is cultivated, yields not its utmost, for want of skill or assiduity in the farmers. If at any time, the public exigencies require, that great numbers shou'd be employed in the public service, the labour of the people furnishes now no superfluities, by which these numbers can be maintain'd. The labourers cannot increase their skill and industry on a sudden. [12] Lands uncultivated cannot be brought into tillage for some years. The armies, mean while, must either make sudden and violent conquests, or disband for want of subsistence. A regular attack or defence, therefore, is not to be expected from such a people, and their soldiers must be as ignorant and unskilful as their farmers and manufacturers.

EVERY thing in the world is purchas'd by labour; and our passions are the only causes of labour. When a nation abounds in manufactures and mechanic arts, the proprietors of land, as well as the farmers, study agriculture as a science, and redouble their industry and attention. The superfluity, which arises from their labour, is not lost; but is exchang'd with the manufacturers for those commodities, which mens luxury now makes them covet. By this means, land furnishes a great deal more of the necessaries of life, than what suffices for those who cultivate it. In times of peace and tranquillity, this superfluity goes to the maintenance of manufacturers and the improvers of liberal arts. But 'tis easy for the public to convert many of these manufacturers into soldiers, and maintain them by that superfluity, which arises from the labour of the farmers. Accordingly we find, that this is the case in all civiliz'd governments. When the sovereign raises an army, what is the consequence? He imposes a tax. This tax obliges all the people to retrench what is least necessary to their subsistence. [13] Those, who labour in such commodities, must either enlist in the troops, or turn themselves to agriculture, and thereby oblige some labourers to enlist for want of business. And to consider the matter abstractly, manufactures increase the power of the state only as they store up so much labour, and that of a kind, which the public may lay claim to, without depriving any one of the necessaries of life. The more labour, therefore, is employ'd beyond mere necessaries, the more powerful is any state; since the persons engag'd in that labour may easily be converted to the public service. In a state without manufactures, there may be the same number of hands; but there is not the same quantity of labour, nor of the same kind. All the labour is there bestow'd upon necessaries, which can admit of little or no abatement.

THUS the greatness of the sovereign and the happiness of the state are, in a great measure, united with regard to trade and manufactures. 'Tis a violent method, and in most cases impracticable, to oblige the labourer to toil, in order to raise from the land more than what subsists himself and family. Furnish him with manufactures and commodities, and he will do it of himself. Afterwards, you will find it easy to seize some part of his superfluous labour, and employ it in the public service, without giving him his wonted return. Being accustom'd to labour, he will think this less [14] grievous, than if, at once, you oblig'd him to an augmentation of labour without any reward. The case is the same with regard to the other members of the state. The greater is the stock of labour of all kinds, the greater quantity may be taken from the heap, without making any sensible alteration upon it.

A PUBLIC granary of corn, a store-house of cloth, a magazine of arms; all these must be allow'd to be real riches and strength in any state. Trade and industry are really nothing; but a stock of labour, which, in time of peace and tranquillity, is employ'd for the ease and satisfaction of individuals, but in the exigencies of state, may, in part, be turn'd to public advantage. Could we convert a city into a kind of fortified camp; and infuse into each breast so martial a genius, and such a passion for public good as to make every one willing to undergo the greatest hardships for the sake of the public; these affections might now, as in antient times, prove alone a sufficient spur to industry, and support the community. It would then be advantageous, as in camps, to banish all arts and luxury; and, by restrictions on equipage and tables, make the provisions and forage last longer than if the army were loaded with a number of superfluous retainers. But as these principles are too disinterested and too difficult to support, 'tis requisite to govern men by other passions, and animate them with [15] a spirit of avarice and industry, art and luxury. The camp is, in this case, loaded with a superfluous retinue; but the provisions flow in proportionably larger. The harmony of the whole is still supported; and the natural bent of mens minds being more complied with, individuals, as well as the public, find their account in the observance of those maxims.

THE same method of reasoning will let us see the advantage of foreign commerce, in augmenting the power of the state, as well as the riches and happiness of the subjects. It increases the stock of labour in the nation; and the sovereign may convert what share of it he finds necessary to the service of the public. Foreign trade, by its imports, furnishes materials for new manufactures. And by its exports, it produces labour in particular commodities, which could not be consum'd at home. In short, a kingdom, that has a large import and export, must abound more with labour, and that upon delicacies and luxuries, than a kingdom, which rests contented with its native commodities. It is, therefore, more powerful, as well as richer and happier. The individuals reap the benefit of these commodities, so far as they gratify the senses and appetites. And the public is also a gainer, while a greater stock of labour is, by this means, stor'd up against any public exigency; that is, a greater number of laborious men are [16] maintain'd, who may be diverted to the public service, without robbing any one of the necessaries, or even the chief conveniencies of life.

IF we consult history, we shall find, that in most nations foreign trade has preceded any refinement in home manufactures, and given birth to domestic luxury. The temptation is stronger to make use of foreign commodities, which are ready for use, and which are entirely new to us, than to make improvements on any domestic commodity, which always advance by slow degrees, and never affect us by their novelty. The profit is also very great, in exporting what is superfluous at home, and what bears no price, to foreign nations, whose soil or climate is not favourable to that commodity. Thus men become acquainted with the pleasures of luxury and the profits of commerce; and their delicacy and industry, being once awaken'd, carry them to farther improvements, in every branch of domestic as well as foreign trade. And this perhaps is the chief advantage, which arises from a commerce with strangers. It rouses men from their lethargic indolence; and presenting the gayer and more opulent part of the nation with objects of luxury, which they never before dream'd of, raises in them a desire of a more splendid way of life than what their ancestors enjoy'd. And, at the same time, the few merchants, who possess the secret of this importation and exportation, make exorbitant [17] profits; and becoming rivals in wealth to the antient nobility, tempt other adventurers to become their rivals in commerce. Imitation soon diffuses all those arts; while domestic manufacturers emulate the foreign in their improvements, and work up every home-commodity to the utmost perfection, of which it is susceptible. Their own steel and iron, in such laborious hands, become equal to the gold and rubies of the Indies.

WHEN the affairs of the society are once brought to this situation, a nation may lose most of its foreign trade, and yet continue a great and powerful people. If strangers will not take any particular commodity of ours, we must cease to labour in it. The same hands will turn themselves towards some refinement in other commodities, which may be wanted at home. And there must always be materials for them to work upon; till every person in the state, who possesses riches, possesses as great plenty of home-commodities, and those in as great perfection, as he desires; which can never possibly happen. China is represented as one of the most flourishing empires in the world; tho' it has very little commerce beyond its own territories.

IT will not, I hope, be considered as a superfluous digression, if I here observe, that, as the multitude of mechanical arts is advantageous, so is the great number of persons, to whose share the productions [18] of these arts fall. A too great disproportion among the citizens weakens any state. Every person, if possible, ought to enjoy the fruits of his labour, in a full possession of all the necessaries, and many of the conveniencies of life. No-one can doubt, but such an equality is most suitable to human nature, and diminishes much less from the happiness of the rich than it adds to that of the poor. It also augments the power of the state, and makes any extraordinary taxes or impositions be paid with much more chearfulness. Where the riches are engross'd by a few, these must contribute very largely to the supplying the public necessities. But when the riches are disperst among multitudes, the burthen feels light on every shoulder, and the taxes make not a very sensible difference on any one's way of living.

ADD to this, that where the riches are in few hands, these must enjoy all the power, and will readily conspire to lay the whole burthen on the poor, and oppress them still farther, to the discouragement of all industry.

IN this circumstance consists the great advantage of England above any nation at present in the world, or that appears in the records of any story. 'Tis true, the English feel some disadvantages in foreign trade by the high price of labour, which is in part the effect of the riches of their artizans, as well as of [19] the plenty of money: But as foreign trade is not the most material circumstance, 'tis not to be put in competition with the happiness of so many millions. And if there were no more to endear to them that free government, under which they live, this alone were sufficient. The poverty of the common people is a natural, if not an infallible consequence of absolute monarchy; tho' I doubt, whether it be always true, on the other hand, that their riches are an infallible consequence of liberty. That seems to depend on particular accidents and a certain turn of thinking, in conjunction with liberty. My lord Bacon, accounting for the great advantages obtain'd by the English in their wars with France, ascribes them chiefly to the superior ease and plenty of the common people, amongst the former; yet the governments of the two kingdoms were, at that time, pretty much alike. Where the labourers and artizans are accustom'd to work for low wages, and to retain but a small part of the fruits of their labour, 'tis difficult for them, even in a free government, to better their condition, or conspire among themselves to heighten their wages. But even where they are accustom'd to a more plentiful way of life, 'tis easy for the rich, in a despotic government, to conspire against them, and throw the whole burthen of the taxes on their shoulders.

[20]

IT may seem an odd position, that the poverty of the common people in France, Italy, and Spain is, in some measure, owing to the superior riches of the soil and happiness of the climate; and yet there want not many reasons to justify this paradox. In such a fine mold or soil as that of those more southern regions, agriculture is an easy art; and one man, with a couple of sorry horses, will be able, in a season, to cultivate as much land as will pay a pretty considerable rent to the proprietor. All the art, which the farmer knows, is to leave his ground fallow for a year, as soon as it is exhausted; and the warmth of the sun alone and temperature of the climate enrich it, and restore its fertility. Such poor peasants, therefore, require only a simple maintenance for their labour. They have no stock nor riches, which claim more; and at the same time, they are for ever dependent on their landlord, who gives no leases, nor fears that his land will be spoil'd by the ill methods of cultivation. In England, the land is rich, but coarse; must be cultivated at a great expence; and produces slender crops, when not carefully manag'd, and by a method, which gives not the full profit but in a course of several years. A farmer, therefore, in England must have a considerable stock and a long lease; which beget proportional profits. The fine vineyards of Champagne and Burgundy, that oft yield to the landlord above five pounds per [21] acre, are cultivated by peasants, who have scarce bread: And the reason is, that such peasants need no stock but their own limbs, along with instruments of husbandry, which they can buy for 20 shillings. The farmers are commonly in some better circumstances in those countries. But the graziers are most at their ease of all those, who cultivate the land. The reason is still the same. Men must have profits proportionable to their expence and hazard. Where so considerable a number of the labouring poor as the peasants and farmers, are in very low circumstances, all the rest must partake of their poverty, whether the government of that nation be monarchical or republican.

WE may form a similar remark with regard to the general history of mankind. What is the reason, why no people living betwixt the tropics cou'd ever yet attain to any art or civility, or reach even any police in their government and any military discipline; while few nations in the temperate climates have been altogether depriv'd of these advantages? 'Tis probable, that one cause of this phaenomenon is the warmth and equality of weather in the torrid zone, that render cloaths and houses less requisite for the inhabitants, and thereby remove, in part, that necessity, which is the great spur to industry and invention. Curis acuens mortalia corda. Not to mention, that the fewer goods or possessions of this kind any people enjoy, [22] the fewer quarrels are likely to arise amongst them; and the less necessity will there be for a settled police or regular authority to protect and defend them from foreign enemies or from each other.

[23]

DISCOURSE II.

Of Luxury.↩

LUXURY is a word of a very uncertain signification, and may be taken in a good as well as a bad sense. In general, it means great refinement in the gratification of the senses; and any degree of it may be innocent or blameable, according to the age or country or condition of the person. The bounds betwixt the virtue and the vice cannot here be fixt exactly, more than in other moral subjects. To imagine, that the gratifying any of the senses, or the indulging any delicacy in meats, drinks, or apparel is, of itself, a vice, can never enter into any head, that is not disorder'd by the frenzies of a fanatical enthusiasm. I have, indeed, heard of a monk abroad, who, because the windows of his cell open'd upon a very noble prospect, made a covenant with his eyes never to turn that way, or receive so sensual a gratification. And such is the crime of drinking Champagne or Burgundy, preferably to small beer or porter. These indulgences are only vices, when they are pursu'd at the expence of some virtue, as liberality or charity: In like manner, as they are follies, when for them a man ruins his fortune, and reduces himself to want and beggary. Where they entrench upon [24] no virtue, but leave ample subject, whence to provide for friends, family, and every proper object of generosity or compassion, they are entirely innocent, and have in every age been acknowledg'd such by almost all moralists. To be entirely occupy'd with the luxury of the table, for instance, without any relish for the pleasures of ambition, study or conversation, is a mark of gross stupidity, and is incompatible with any vigour of temper or genius. To confine one's expence entirely to such a gratification, without regard to friends or family, is an indication of a heart entirely devoid of humanity or benevolence. But if a man reserve time sufficient for all laudable pursuits, and money sufficient for all generous purposes, he is free from every shadow of blame or reproach.

SINCE luxury may be consider'd, either as innocent or blameable, one may be surpris'd at those preposterous opinions, which have been entertain'd concerning it; while men of libertine principles bestow praises even on vitious luxury, and represent it as highly advantageous to society; and on the other hand, men of severe morals blame even the most innocent luxury, and represent it as the source of all the corruptions, disorders, and factions, incident to civil government. We shall here endeavour to correct both these extremes, by proving, first, that the ages of refinement and luxury are both the happiest and most virtuous; secondly, [25] that wherever luxury ceases to be innocent, it also ceases to be beneficial, and when carry'd a degree too far, is a quality pernicious, tho' perhaps not the most pernicious, to political society.

To prove the first point, we need but consider the effects of luxury both on private and on public life. Human happiness, according to the most receiv'd notions, seems to consist in three ingredients, action, pleasure, and indolence; and tho' these ingredients ought to be mixt in different proportions, according to the particular dispositions of the person, yet no one ingredient can be entirely wanting, without destroying, in some measure, the relish of the whole composition. Indolence or repose, indeed, seems not, of itself, to contribute much to our enjoyment; but like sleep, is requisite as an indulgence to the weakness of human nature, which cannot support an uninterrupted course of business or pleasure. That quick march of the spirits, which takes a man from himself, and chiefly gives satisfaction, does in the end exhaust the mind, and requires some intervals of repose, which, tho' agreeable for a moment, yet, if prolong'd, beget a languor and lethargy, that destroy all enjoyment. Education, custom, and example have a mighty influence in turning the mind to any of these pursuits; and it must be own'd, that, where they promote a relish for action and pleasure, they are so far favourable to human happiness. In times, [26] when industry and arts flourish, men are kept in perpetual occupation, and enjoy, as their reward, the occupation itself, as well as those pleasures, which are the fruits of their labour. The mind acquires new vigour; enlarges its powers and faculties; and by an affiduity in honest industry, both satisfies its natural appetites, and prevents the growth of unnatural ones, which commonly spring up, when nourish'd with ease and idleness. Banish those arts from society, you deprive men both of action and of pleasure; and leaving nothing but indolence in their place, you even destroy the relish of indolence, which never is agreeable, but when it succeeds to labour, and recruits the spirits, exhausted by too much application and fatigue.

ANOTHER advantage of industry and of refinements in the mechanical arts is, that they commonly produce some refinements in the liberal arts; nor can the one be carried to perfection, without being accompany'd, in some degree, with the other. The same age, which produces great philosophers and politicians, renown'd generals and poets, usually abounds with skilful weavers and ship-carpenters. We cannot reasonably expect, that a piece of woolen cloth will be wrought to perfection in a nation, that is ignorant of astronomy, or where ethics are neglected. The spirit of the age affects all the arts; and the minds of men, being once rous'd from their lethargy, and put into a fermentation, [27] turn themselves on all fides, and carry improvements into every art and science. Profound ignorance is totally banish'd, and men enjoy the privilege of rational creatures, to think as well as to act, to cultivate the pleasures of the mind as well as those of the body.

THE more these refin'd arts advance, the more sociable do men become; nor is it possible, that, when enrich'd with science, and possest of a fund of conversation, they should be contented to remain in solitude, or live with their fellow citizens in that distant manner, which is peculiar to ignorant and barbarous nations. They flock into cities; love to receive and communicate knowledge; to show their wit or their breeding; their taste in conversation or living, in cloaths or furniture. Curiosity allures the wise: Vanity the foolish: And pleasure both. Particular clubs and societies are every where form'd: Both sexes meet in an easy and sociable manner, and mens tempers, as well as behaviour, refine a-pace. So that beside the improvements they receive from knowledge and the liberal arts, 'tis impossible but they must feel an increase of humanity, from the very habit of conversing together, and contributing to each other's pleasure and entertainment. Thus industry, knowledge, and humanity are linkt together by an indissoluble chain, and are found, from experience as [28] well as reason, to be peculiar to the more polish'd and luxurious ages.

NOR are these advantages attended with disadvantages, that bear any proportion to them. The more men refine upon pleasure, the less will they indulge in excesses of any kind; because nothing is more destructive to true pleasure than such excesses. One may safely affirm, that the Tartars are oftner guilty of beastly gluttony, when they feast on their dead horses, than European courtiers with all their refinements of cookery. And if libertine love, or even infidelity to the marriage-bed, be more frequent in polite ages, when it is often regarded only as a piece of gallantry, drunkenness, on the other hand, is much less common: A vice more odious and more pernicious both to mind and body. And in this matter I would appeal not only to an Ovid or a Petronius, but to a Seneca or a Cato. We know, that Caesar, during Cataline's conspiracy, being necessitated to put into Cato's hands a billetdoux, which discover'd an intrigue with Servilia, Cato's own sister, that stern philosopher threw it back to him with indignation, and in the bitterness of his wrath gave him the appellation of drunkard, as a term more opprobrious than that with which he cou'd more justly have reproach'd him.

BUT industry, knowledge, and humanity are not advantageous in private life alone: They diffuse their beneficial influence on the Public, and render [29] the government as great and flourishing as they make individuals happy and prosperous. The encrease and consumption of all the commodities, which serve to the ornament and pleasure of life, are advantageous to society; because at the same time that they multiply those innocent gratifications to individuals, they are a kind of store-house of labour, which, in the exigencies of state, may be turn'd to the public service. In a nation, where there is no demand for such superfluities, men sink into indolence, lose all the enjoyment of life, and are useless to the public, which cannot maintain nor support its fleets and armies, from the industry of such slothful members.

THE bounds of all the European kingdoms are, at present, pretty near the same they were two hundred years ago: But what a difference is there in the power and grandeur of those kingdoms? Which can be ascrib'd to nothing but the encrease of art and industry. When Charles the VIII. of France invaded Italy, he carry'd with him about 20,000 men: And yet this armament so exhausted the nation, as we learn from Guicciardin, that for some years it was not able to make so great an effort. The late king of France, in time of war, kept in pay above 400,000 men; [*] tho' from Mazarine's death to his own he was engag'd in a course of wars, that lasted near thirty years.

[30]

THIS industry is much promoted by the knowledge, inseparable from the ages of arts and luxury; as on the other hand, this knowledge enables the public to make the best advantage of the industry of its subjects. Laws, order, police, discipline; these can never be carry'd to any degree of perfection, before human reason has refin'd itself by exercise, and by an application to the more vulgar arts, at least, of commerce and manufactures. Can we expect, that a government will be well model'd by a people, who know not how to make a spinning wheel, or to employ a loom to advantage? Not to mention, that all ignorant ages are infested with superstition, which throws the government off its bias, and disturbs men in the pursuit of their interest and happiness.

KNOWLEDGE in the arts of government naturally begets mildness and moderation, by instructing men in the advantages of humane maxims above rigour and severity, which drive subjects into rebellion, and render the return to submission impracticable, by cutting off all hopes of pardon. When mens temper is soften'd as well as their knowledge improv'd, this humanity appears still more conspicuous, and is the chief characteristic, that distinguishes a civiliz'd age from times of barbarity and ignorance. Factions are then less inveterate; revolutions less tragical; authority less severe; [31] and seditions less frequent. Even foreign wars abate of their cruelty; and after the field of battle, where honour and interest steel men against compassion as well as fear, the combatants divest themselves of the brute, and resume the man.

NOR need we fear, that men, by losing their ferocity, will lose their martial spirit, or become less undaunted and vigorous in defence of their country or their liberty. The arts have no such effect in enervating either the mind or body. On the contrary, industry, their inseparable attendant, adds new force to both. And if anger, which is said to be the whetstone of courage, loses somewhat of its asperity, by politeness and refinement; a sense of honour, which is a stronger, more constant, and more governable principle, acquires fresh vigour by that elevation of genius, which arises from knowledge and a good education. Add to this, that courage can neither have any duration, nor be of any use, when not accompany'd with discipline and martial skill, which are seldom found among a barbarous people. The antients remark'd that Datames was the only barbarian that ever knew the art of war. And Pyrrhus seeing the Romans marshal their army with some art and skill, said with surprize These barbarians have nothing barbarous in their discipline! 'Tis observable, that as the old Romans, by applying themselves solely to war, were the only unciviliz'd people that [32] ever possest military discipline; so the modern Italians are the only civiliz'd people, among Europeans, that ever wanted courage and a martial spirit. Those who wou'd ascribe this effeminacy of the Italians to their luxury or politeness, or application to the arts, need but consider the French and English, whose bravery is as uncontestable as their love of luxury, and their assiduity in commerce. The Italian historians give us a more satisfactory reason for this degeneracy of their countrymen. They shew us how the sword was dropt at once by all the Italian sovereigns; while the Venetian aristocracy was jealous of its subjects, the Florentine democracy apply'd itself entirely to commerce; Rome was govern'd by priests, and Naples by women. War then became the business of soldiers of fortune, who spar'd one another, and to the astonishment of the world, cou'd engage a whole day in what they call'd a battle, and return at night to their camps without the least bloodshed.

WHAT has chiefly induc'd severe moralists to declaim against luxury and refinement in pleasure is the example of antient Rome, which, joining, to its poverty and rusticity, virtue and public spirit, rose to such a surprising height of grandeur and liberty; but having learn'd from its conquer'd provinces the Grecian and Asiatic luxury, fell into every kind of corruption; whence arose sedition and civil wars, attended at last with the total loss of liberty. [33] All the Latin classics, whom we peruse in our infancy, are full of these sentiments, and universally ascribe the ruin of their state to the arts and riches imported from the East: insomuch that Sallust represents a taste for painting as a vice no less than lewdness and drinking. And so popular were these sentiments during the latter ages of the republic, that this author abounds in praises of the old rigid Roman virtue, tho' himself the most egregious instance of modern luxury and corruption; speaks contemptuously of Grecian eloquence, tho' the most elegant writer in the world; nay, employs preposterous digressions and declamations to this purpose, tho' a model of taste and correctness.

BUT it would be easy to prove, that these writers mistook the cause of the disorders in the Roman state, and ascrib'd to luxury and the arts what really proceeded from an ill model'd government, and the unlimited extent of conquests. Luxury or refinement on pleasure has no natural tendency to beget venality and corruption. The value, which all men put upon any particular pleasure, depends on comparison and experience; nor is a porter less greedy of money, which he spends on bacon and brandy, than a courtier, who purchases champagne and ortolans. Riches are valuable at all times and to all men, because they always purchase pleasures, such as men are accustom'd to and desire; nor can any thing restrain or regulate the love of money but [34] a sense of honour and virtue; which, if it be not nearly equal at all times, will naturally abound most in ages of luxury and knowledge.

OF all European kingdoms, Poland seems the most defective in the arts of war as well as peace, mechanical as well as liberal; and yet 'tis there that venality and corruption do most prevail. The nobles seem to have preserv'd their crown elective for no other purpose, but regularly to sell it to the highest bidder. This is almost the only species of commerce, with which that people are acquainted.

THE liberties of England, so far from decaying since the origin of luxury and the arts, have never flourish'd so much as during that period. And tho' corruption may seem to encrease of late years; this is chiefly to be ascrib'd to our establish'd liberty, when our princes have found the impossibility of governing without parliaments, or of terrifying parliaments by the fantom of prerogative. Not to mention, that this corruption or venality prevails infinitely more among the electors than the elected; and therefore cannot justly be ascrib'd to any refinements in luxury.

IF we consider the matter in a proper light, we shall find, that luxury and the arts are rather favourable to liberty, and have a natural tendency to preserve, if not produce a free government. In [35] rude unpolish'd nations, where the arts are neglected, all the labour is bestow'd on the cultivation of the ground; and the whole society divides into two classes, proprietors of land, and their vassals or tenants. The latter are necessarily dependent and fitted for slavery and subjection; especially where they possess no riches, and are not valu'd for their knowledge in agriculture; as must always be the case where the arts are neglected. The former naturally erect themselves into petty tyrants; and must either submit to an absolute master for the sake of peace and order; or if they will preserve their independency, like the Gothic barons, they must fall into feuds and contests amongst themselves, and throw the whole society into such confusion as is perhaps worse than the most despotic government. But where luxury nourishes commerce and industry, the peasants, by a proper cultivation of the land, become rich and independent; while the tradesmen and merchants acquire a share of the property, and draw authority and consideration to that middling rank of men; who are the best and firmest basis of public liberty. These submit not to slavery, like the poor peasants, from poverty and meanness of spirit; and having no hopes of tyrannizing over others, like the barons, they are not tempted, for the sake of that gratification, to submit to the tyranny of their sovereign. They covet equal laws, which may secure their property, [36] and preserve them from monarchical, as well as aristocratical tyranny.

THE house of commons is the support of our popular government; and all the world acknowledge, that it ow'd its chief influence and consideration to the encrease of commerce, which threw such a balance of property into the hands of the commons. How inconsistent, then, is it to blame so violently luxury, or a refinement in the arts, and to represent it as the bane of liberty and public spirit!

TO declaim against present times, and magnify the virtue of remote ancestors, is a propensity almost inherent in human nature; and as the sentiments and opinions of civiliz'd ages alone are transmitted to posterity, hence it is that we meet with so many severe judgments pronounc'd against luxury and even science, and hence it is that at present we give so ready an assent to them. But the fallacy is easily perceiv'd from comparing different nations that are contemporaries; where we both judge more impartially, and can better set in opposition those manners with which we are sufficiently acquainted. Treachery and cruelty, the most pernicious and most odious of all vices, seem peculiar to unciviliz'd ages; and by the refin'd Greeks and Romans were ascrib'd to all the barbarous nations, which surrounded them. They [37] might justly, therefore, have presum'd, that their own ancestors, so highly celebrated, possest no greater virtue, and were as much inferior to their posterity in honour and humanity as in taste and science. An antient Frank or Saxon may be highly extoll'd: But I believe every man would think his life or fortune much less secure in the hands of a Moor or Tartar, than in those of a French or English gentleman, the rank of men the most civiliz'd, in the most civiliz'd nations.

WE come now to the second position, which we propos'd to illustrate, viz. that as innocent luxury or a refinement in pleasure is advantageous to the public; so wherever luxury ceases to be innocent, it also ceases to be beneficial, and when carry'd a degree farther, begins to be a quality pernicious, tho', perhaps, not the most pernicious, to political society.

LET us consider what we call vicious luxury. No gratification, however sensual, can, of itself, be esteem'd vicious. A gratification is only vicious, when it engrosses all a man's expence, and leaves no ability for such acts of duty and generosity as are requir'd by his situation and fortune. Suppose, that he correct the vice, and employ part of his expence in the education of his children, in the support of his friends, and in relieving the poor; would any prejudice result to society? On the contrary, [38] the same consumption would arise; and that labour, which, at present, is employ'd only in producing a slender gratification to one man, would relieve the necessitous, and bestow satisfaction on hundreds. The same care and toil, which raise a dish of peas at Christmas, would give bread to a whole family during six months. To say, that, without a vicious luxury, the labour would not have been employ'd at all, is only to say, that there is some other defect in human nature, such as indolence, selfishness, inattention to others, for which luxury, in some measure, provides a remedy; as one poison may be an antidote to another. But virtue, like wholesome food, is better than poisons, however corrected.

SUPPOSE the same number of men, that are, at present, in Britain, with the same soil and climate; I ask, is it not possible for them to be happier, by the most perfect way of life, that can be imagin'd, and by the greatest reformation, which omnipotence itself could work in their temper and disposition? To assert, that they cannot, appears evidently ridiculous. As the land is able to maintain more than all its inhabitants, they cou'd never, in such an Utopian state, feel any other ills, than those which arise from bodily sickness; and these are not the half of human miseries. All other ills spring from some vice, either in ourselves or others; and even many of our diseases proceed from the same [39] origin. Remove the vices, and the ills follow. You must only take care to remove all the vices. If you remove part, you may render the matter worse. By banishing vicious luxury, without curing sloth and an indifference to others, you only diminish industry in the state, and add nothing to mens charity or their generosity. Let us, therefore, rest contented with asserting, that two opposite vices in a state may be more advantageous than either of them alone; but let us never pronounce vice, in it self, advantageous. Is it not very inconsistent for an author to assert in one page, that moral distinctions are inventions of politicians for public interest; and in the next page maintain, that vice is advantageous to the public? [*] And indeed, it seems, upon any system of morality, little less than a contradiction in terms, to talk of a vice, that is in general beneficial to society.

I THOUGHT this reasoning necessary, in order to give some light to a philosophical question, which has been much disputed in Britain. I call it a philosophical question, not a political one. For whatever may be the consequence of such a miraculous transformation of mankind, as would endow them with every species of virtue, and free them from every vice, this concerns not the magistrate, who aims only at possibilities. He cannot cure every vice, by substituting a virtue in its place. Very [40] often he can only cure one vice by another; and in that case, he ought to prefer what is least pernicious to society. Luxury, when excessive, is the source of many ills; but is in general preferable to sloth and idleness, which wou'd commonly succeed in its place, and are more pernicious both to private persons and to the public. When sloth reigns, a mean uncultivated way of life prevails amongst individuals, without society, without enjoyment. And if the sovereign, in such a situation, demands the service of his subjects, the labour of the state suffices only to furnish the necessaries of life to the labourers, and can afford nothing to those, who are employ'd in the public service.

[41]

DISCOURSE III.

Of Money.↩

MONEY is not, properly speaking, one of the subjects of commerce; but only the instrument, which men have agreed upon to facilitate the exchange of one commodity for another. 'Tis none of the wheels of trade: 'Tis the oil, which renders the motion of the wheels more smooth and easy. If we consider any one kingdom by itself, 'tis evident, that the greater or less plenty of money is of no consequence; since the prices of commodities are always proportion'd to the plenty of money, and a crown in Harry the VII's. time serv'd the same purpose as a pound does at present. 'Tis only the public, that draws any advantage from the greater plenty of money; and that only in its wars and negociations with foreign states. And this is the reason, why all rich and trading countries, from Carthage to Britain and Holland, have employ'd mercenary troops, which they hir'd from their poorer neighbours. Were they to make use of their native subjects, they would find less advantage from their superior riches, and from their great plenty of gold and silver; since the pay of all their servants must rise in proportion to the public opulence. Our small army in Britain [42] of 20,000 men are maintain'd at as great expence as a French army thrice as numerous. The English fleet, during the late war, requir'd as much money to support it as all the Roman legions, which kept the whole world in subjection, during the time of the emperors[*]

THE greater number of people and their greater industry are serviceable in all cases; at home and abroad, in private and in public. But the greater plenty of money is very limited in its use, and may even sometimes be a loss to a nation in its commerce with foreigners.

[43]

THERE seems to be a happy concurrence of causes in human affairs, which check the growth of trade and riches, and hinder them from being confin'd entirely to one people; as might naturally at first be dreaded from the advantages of an establish'd commerce. Where one nation has got the start of another in trade, 'tis very difficult for the latter to regain the ground it has lost; because of the superior industry and skill of the former, and the greater stocks, which its merchants are possest' of, and which enable them to trade for so much smaller profits. But these advantages are compensated, in some measure, by the low prices of labour in every nation, that has not an extensive commerce, and does not very much abound in gold and silver. Manufactures, therefore, gradually shift their places, leaving those countries and provinces, which they have already enrich'd, and flying to others, whither they are allur'd by the cheapness of provisions and labour; till they have enrich'd these also, and are again banish'd by the same causes. And in general, we may observe, that the dearness of every thing, from plenty of money, is a disadvantage, that attends an establish'd commerce, and sets bounds to it in every country, by enabling the poorer states to undersell the richer in all foreign markets.

THIS has made me entertain a great doubt concerning the benefit of banks and paper credit, which [44] are so generally esteem'd advantageous to every nation. That provisions and labour shou'd become dear by the encrease of trade and money, is, in many respects, an inconvenience; but an inconvenience that is unavoidable, and the effect of that public wealth and prosperity, which are the end of all our wishes. 'Tis compensated by the advantages we reap from the possession of these precious metals, and the weight which they give the nation in all foreign wars and negotiations. But there appears no reason for encreasing that inconvenience by a counterfeit money, which foreigners will never accept of, and which any great disorder in the state will reduce to nothing. There are, 'tis true, many people in every rich state, who, having large sums of money, wou'd prefer paper with good security; as being of more easy transport and more safe custody. If the public provide not a bank, private bankers will take advantage of this circumstance; as the goldsmiths formerly did in London, or as the bankers do at present in Dublin: And therefore 'tis better, it may be thought, that a public company should enjoy the benefit of that paper credit, which always will have place in every opulent kingdom. But to endeavour artificially to encrease such a credit, can never be the interest of any trading nation; but must lay them under disadvantages, by encreasing money beyond its natural proportion to labour and commodities, and thereby heightening their price to the merchant [45] and manufacturer. And in this view, it must be allow'd, that no bank cou'd be more advantageous than such a one as lockt up all the money it receiv'd, and never augmented the circulating coin, as is usual, by returning part of its treasure into commerce. A public bank, by this expedient, might cut off much of the dealings of private bankers and money jobbers; and tho' the state bore the charge of salaries to the directors and tellers of this bank, (for according to the preceeding supposition, it would have no profit from its dealings) the national advantage, resulting from the low price of labour and the destruction of paper credit, would be a sufficient compensation. Not to mention, that so large a sum, lying ready at command, would be a great convenience in times of public danger and distress; and might be replac'd at leisure, when peace and tranquillity were restor'd to the nation.

BUT of this subject of paper credit, we shall treat more largely hereafter. And I shall finish this essay of money, by proposing and explaining two observations, which may, perhaps, serve to employ the thought of our speculative politicians. For to these only I all along address myself. 'Tis enough that I submit to the ridicule sometimes, in this age, attach'd to the character of a philosopher, without adding to it that which belongs to a projector.

[46]

I. 'T WAS a shrewd observation of Anacharsis [*] the Scythian, who had never seen money in his own country, that gold and silver seem'd to him of no use to the Greeks, but to assist them in numeration and arithmetic. 'Tis indeed evident, that money is nothing but the representation of labour and commodities, and serves only as a method of rating or estimating them. Where coin is in greater plenty; as a greater quantity of it is then requir'd to represent the same quantity of goods; it can have no effect, either good or bad, taking a nation within itself: no more than it wou'd make any alteration on a merchant's books, if instead of the Arabian method of notation, which requires few characters, he shou'd make use of the Roman, which requires a great many. Nay the greater plenty of money, like the Roman characters, is rather inconvenient and troublesome; and requires greater care to keep and transport it. But notwithstanding this conclusion, which must be allowed just, 'tis certain, that since the discover of the mines in America, industry has encreas'd in all the nations of Europe, except in the possessors of those mines; and this may justly be ascrib'd, amongst other reasons, to the encrease of gold and silver. Accordingly we find, that in every kingdom, into which money begins to flow in greater abundance than formerly, every thing takes a new face; labour and [47] industry gain life; the merchant becomes more enterprizing; the manufacturer more diligent and skillful; and even the farmer follows his plough with greater alacrity and attention. This is not easily to be accounted for, if we consider only the influence, which a greater abundance of coin has in the kingdom itself, by heightening the price of commodities, and obliging every one to pay a greater number of these little yellow or white pieces for every thing he purchases. And as to foreign trade, it appears, that great plenty of money is rather disadvantageous, by raising the price of every kind of labour.

To account, then, for this phaenomenon, we must consider, that tho' the high price of commodities be a necessary consequence of the encrease of gold and silver, yet it follows not immediately upon that encrease; but some time is requir'd before the money circulate thro' the whole state, and make its effects be felt on all ranks of people. At first, no alteration is perceiv'd; by degrees, it raises the price first of one commodity, then of another; till the whole at last rises to a just proportion, with the new quantity of specie, which is in the kingdom. In my opinion, 'tis only in this interval or intermediate situation, betwixt the acquisition of money and rise of prices, that the encreasing quantity of gold and silver is favourable to industry. When any quantity of money is imported into a nation, it is [48] not at first disperst into many hands; but is confin'd to the coffers of a few persons, who immediately seek to employ it to the best advantage. Here are a set of manufacturers or merchants, we shall suppose, who have receiv'd returns of gold and silver for goods, which they sent to Cadiz. They are thereby enabled to employ more workmen than formerly, who never dream of demanding higher wages, but are glad of employment from such good paymasters. If workmen become scarce, the manufacturer gives higher wages; but at first requires an encrease of labour, and this is willingly submitted to by the artizan, who can now eat and drink better to compensate his additional toil and fatigue. He carries his money to market, where he finds every thing at the same price as formerly, but returns with greater quantity and of better kinds, for the use of his family. The farmer and gardener, finding that all their commodities are taken off, apply themselves with alacrity to the raising of more; and at the same time, can afford to take better and more cloaths from their tradesmen, whose price is the same as formerly, and their industry only whetted by so much new gain. 'Tis easy to trace the money in its progress thro' the whole commonwealth; where we shall find, that it must first quicken the diligence of every individual, before it encrease the price of labour.

[49]

AND that the specie may encrease to a considerable pitch, before it have this latter effect, appears, amongst other reasons, from the frequent operations of the French king on the money; where it was always found, that the augmenting the numerary value did not produce a proportional rise of the prices, at least for some time. In the last year of Louis the XIV. money was rais'd three sevenths, but prices augmented only one. Corn in France is now sold at the same price, or for the same number of livres, it was in 1683, tho' silver was then at 30 livres the mark, and is now at 50. [*] Not to mention, the [50] great addition of gold and silver, which may have come into that kingdom, since the former period.

FROM the whole of this reasoning we may conclude, that 'tis of no manner of consequence, with regard to the domestic happiness of a state, whether money be in a greater or less quantity. The good policy of the magistrate consists only in keeping it, if possible, still encreasing; because, by that means, he keeps a spirit of industry alive in the nation, and encreases the stock of labour, wherein consists all real power and riches. A nation, whose money decreases, is actually, at that time, much weaker and more miserable, than another nation, who possesses no more money, but is on the encreasing hand. This will be easily accounted for, if we consider, that the alterations in the quantity of money, either on the one side or the other, are not immediately attended with proportionable alterations in the prices of commodities. There is always an interval before matters be adjusted to their new situation; and this interval is as pernicious to industry, when gold and silver are diminishing, as it is advantageous, when these metals are encreasing. The workman has not the same employment from the manufacturer and merchant; tho' he pays the same price for every thing in the market. The farmer cannot dispose of his corn and cattle; tho' he must pay the same rent to his landlord. The [51] poverty and beggary and sloth, which must ensue, are easily foreseen.

II. The second observation I propos'd to make with regard to money, may be explain'd after the following manner. There are some kingdoms, and many provinces in Europe, (and all of them were once in the same condition) where money is so scarce, that the landlord can get none at all from his tenants; but is oblig'd to take his rent in kind, and either to consume it himself, or transport it to places, where he may find a market. In those countries, the prince can levy few or no taxes, but in the same manner: And as he will receive very small benefit from impositions so pay'd, 'tis evident, that such a kingdom has very little force even at home; and cannot maintain fleets and armies to the same extent, as if every part of it abounded in gold and silver. There is surely a greater disproportion betwixt the force of Germany at present and what it was three centuries ago, [*] than there is in its industry, people and manfactures. The Austrian dominions in the empire are in general well peopled and well cultivated, and are of great extent, but have not a proportionable weight in the balance of Europe; proceeding, as is commonly suppos'd, from their scarcity of money. How do all these facts agree with that principle of [52] reason, that the quantity of gold and silver is in itself altogether indifferent? According to that principle, wherever a sovereign has numbers of subjects, and these have plenty of commodities, he shou'd, of course, be great and powerful, and they rich and happy, independent of the greater or lesser abundance of the precious metals. These admit of divisions and sub-divisions to a great extent; and where they wou'd become so small as to be in danger of being lost, 'tis easy to mix them with a baser metal, as is practis'd in some countries of Europe; and by that means raise them to a bulk more sensible and convenient. They still serve the same purposes of exchange, whatever their number may be, or whatever colour they may be suppos'd to have.

To these difficulties I answer, that the effect, here suppos'd to flow from scarcity of money, really arises from the manners and customs of the inhabitants, and that we mistake, as is usual, a collateral effect for a cause. The contradiction is only apparent; but it requires some thought and reflection to discover the principles, by which we can reconcile reason to experience.

It seems a maxim almost self-evident, that the prices of every thing depend on the proportion betwixt commodities and money, and that any considerable alteration on either of these has the same [53] effect either of heightening or diminishing the price. Encrease the commodities, they become cheaper: Encrease the money, they rise in their value. As on the other hand, a diminution of the former, and that of the latter have contrary tendencies.

'TIS also evident, that the prices do not so much depend on the absolute quantity of commodities and of money, which are in a nation; as on that of the commodities, which come or may come to market, and of the money, which circulates. If the coin be lockt up in chests, 'tis the same thing with regard to prices, as if it were annihilated: If the commodities be hoarded in granaries, a like effect follows. As the money and commodities, in these cases, never meet, they cannot affect each other. Were we, at any time, to form conjectures concerning the prices of provisions, the corn, which the farmer must reserve for the maintenance of himself and family, ought never to enter into the estimation. 'Tis only the overplus, compar'd to the demand, that determines the value.

To apply these principles, we must consider, that in the first and more uncultivated ages of any state, e're fancy has confounded her wants with those of nature, men, contented with the productions of their own fields, or with those rude preparations, which they themselves can work upon [54] them, have little occasion for exchange, or at least for money, which, by agreement, is the common measure of exchange. The wool of the farmer's own flock, spun in his own family, and wrought by a neighbouring weaver, who receives his payment in corn or wool, suffices for furniture and cloathing. The carpenter, the smith, the mason, the taylor are retain'd by wages of a like nature; and the landlord himself, dwelling in the neighbourhood, is contented to receive his rent in the commodities rais'd by the farmer. The greatest part of these he consumes at home, in rustic hospitality: The rest, perhaps, he disposes of for money to the neighbouring town, whence he draws the materials of his expence and luxury.

BUT after men begin to refine on all these enjoyments, and live not always at home, nor are contented with what can be rais'd in their neighbourhood, there is more exchange and commerce of all kinds, and more money enters into that exchange. The tradesmen will not be paid in corn; because they want something more than barely to eat. The farmer goes beyond his own parish for the commodities he purchases, and cannot always carry his commodities to the merchant, who supplies him. The landlord lives in the capital or in a foreign country; and demands his rent in gold and silver, which can easily be transported to him. Great undertakers and manufacturers and merchants [55] arise in every commodity; and these can conveniently deal in nothing but in specie. And consequently, in this situation of society, the coin enters into many more contracts, and by that means is much more employ'd than in the former.

THE necessary effect is, that provided the money does not encrease in the nation, every thing must become much cheaper in times of industry and refinement, than in rude, uncultivated ages. 'Tis the proportion betwixt the money, that circulates, and the commodities in the market, that determines the prices. Goods, that are consum'd at home, or exchang'd with other goods in the neighbourhood, never come to market; they affect not, in the least, the current specie; with regard to it they are as if totally annihilated; and consequently this method of using them sinks the proportion on the side of the commodities, and encreases the prices. But after money enters into all contracts and sales, and is every where the measure of exchange, the same national cash has a much greater task to perform; all commodities are then in the market; the sphere of circulation is enlarg'd; 'tis the same case as if that individual sum were to serve a larger kingdom; and therefore, the proportion being here diminish'd on the side of the money, every thing must become cheaper, and the prices gradually fall.

[56]

BY the most exact computations, that have been form'd all over Europe, after making allowance for the change in the numerary value or the denomination, 'tis found, that the prices of all things have only risen three, or at most four times since the discovery of the West Indies. But will any one assert, that there is no more than four times the coin in Europe, that was in the fifteenth century and the centuries preceding it? The Spaniards and Portuguese from their mines, the English, French and Dutch, by their African trade, and by their interlopers in the West Indies, bring home about seven millions a year, of which not above a tenth part goes to the East Indies. This sum alone in five years would probably double the antient stock of money in Europe. And no other satisfactory reason can be given, why all prices have not risen to a much more exorbitant height, except that deriv'd from a change of customs and manners. Besides, that more commodities are produc'd by additional industry, the same commodities come more to market, after men depart from their antient simplicity of manners. And tho' this encrease has not been equal to that of money, it has, however, been considerable, and has preserv'd the proportion betwixt coin and commodities nearer the antient standard.

WERE the question propos'd, which of these methods of living in the people, the simple or the [57] refin'd, is the most advantageous to the state or public, I shou'd, without much scruple, prefer the latter, in a view to politics at least; and should produce this as an additional reason for the encouragement of trade and manufactures.

WHEN men live in the antient simple manner, and supply all their necessities from their domestic industry or from the neighbourhood, the sovereign can levy no taxes in money from a considerable part of his subjects; and if he will impose on them any burthens, he must take his payment in commodities, with which alone they abound; a method attended with such great and obvious inconveniencies, that they need not here be insisted on. All the money he can pretend to raise must be from his principal cities, where alone it circulates; and these, 'tis evident, cannot afford him so much as the whole state cou'd, did gold and silver circulate thro' the whole. But besides this obvious diminution of the revenue, there is also another cause of the poverty of the public in such a situation. Not only the sovereign receives less money, but the same money goes not so far as in times of industry and general commerce. Every thing is dearer, where the gold and silver are suppos'd equal; and that because fewer commodities come to market, and the whole coin bears a higher proportion to what is to be purchas'd by it; [58] whence alone the prices of every thing are fix'd and determin'd.

HERE then we may learn the fallacy of the remark, often to be met with in historians, and even in common conversation, that any particular state is weak, tho' fertile, populous, and well cultivated, merely because it wants money. It appears, that the want of money can never injure any state within itself: For men and commodities are the real strength of any community. 'Tis the simple manner of living which here hurts the public, by confining the gold and silver to few hands, and preventing its universal diffusion and circulation. On the contrary, industry and refinements of all kinds incorporate it with the whole state, however small its quantity may be: They digest it into every vein, so to speak; and make it enter into every transaction and contract. No hand is entirely empty of it; and as the prices of every thing fall by that means, the sovereign has a double advantage: He may draw money by his taxes from every part of the state, and what he receives goes farther in every purchase and payment.

WE may infer, from a comparison of prices, that money is not more plentiful in China, than it was in Europe three centuries ago: But what immense power is that empire possest of, if we may judge by the civil and military list, maintain'd by [59] it? Polybius [*] tells us, that provisions were so cheap in Italy during his time, that in some places the stated club in the inns was a semis a head, little more than a farthing: Yet the Roman power had even then subdu'd the whole known world. About a century before that period, the Carthaginian ambassadors said, by way of raillery, that no people liv'd more sociably amongst themselves than the Romans; for that in every entertainment, which, as foreign ministers, they receiv'd, they still observ'd the same plate at every table. [†] The absolute quantity of the precious metals is a matter of great indifference. There are only two circumstances of any importance, viz. their gradual encrease, and their thorough concoction and circulation thro' the state; and the influence of both these circumstances has been here explained.

IN the following discourse we shall see an instance of a like fallacy, as that above mention'd; where a collateral effect is taken for a cause, and where a consequence is ascrib'd to the plenty of money; tho' it be really owing to a change in the manners and customs of the people.

[61]

DISCOURSE IV.

Of Interest.↩