FRANCIS HOTOMAN,

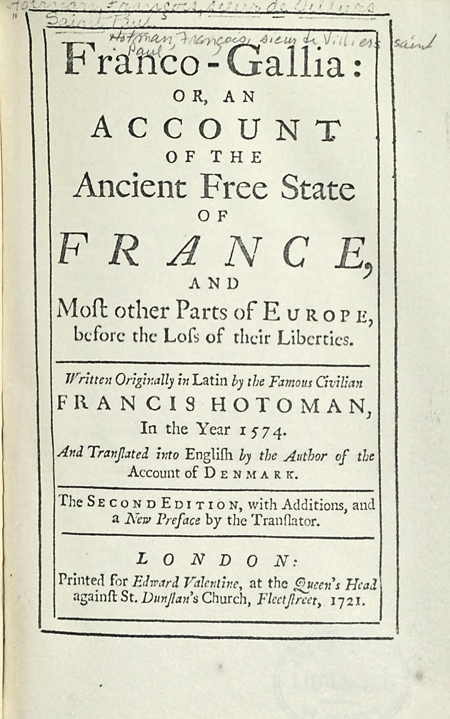

Franco-Gallia: Or, an Account of the Ancient Free State of France, and most other Parts of Europe, before the Loss of their Liberties (1574, 1721)

|

[Created: 12 September, 2024]

[Updated: 12 September, 2024] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, Franco-Gallia: Or, an Account of the Ancient Free State of France, and most other Parts of Europe, before the Loss of their Liberties. Written Originally in Latin by the Famous Civilian Francis Hotoman, In the Year 1574. And Translated into English by the Author of the Account of Denmark. The Second Edition, with Additions, and a New Preface by the Translator. (London: Edward Valentine, 1721).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1721-Hotman_Francgallia/Hotman_Francogallia1721-ebook.html

Francis Hotoman, Franco-Gallia: Or, an Account of the Ancient Free State of France, and most other Parts of Europe, before the Loss of their Liberties. Written Originally in Latin by the Famous Civilian Francis Hotoman, In the Year 1574. And Translated into English by the Author of the Account of Denmark. The Second Edition, with Additions, and a New Preface by the Translator. London: Printed for Edward Valentine, at the Queen's Head against St. Dunstan's Church, Fleetstreet, 1721.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

INDEX OF THE CHAPTERS ↩

- CHAP. I. The State of Gaul before it was reduced into the Form of a Roman ProvincePage 1

- CHAP. II. Probable Conjectures concerning the Ancient Language of the Gauls. 8

- CHAP. III. The State of Gaul, after it was reduced into the Form of a Province by the Romans. 14

- CHAP. IV. Of the Original of the Franks, who having possessed themselves of Gallia, changed its Name into that of Francia, or Francogallia. 20

- CHAP. V. Of the Name of the Franks, and their sundry Excursions; and what time they first began to establish a Kingdom in Gallia. 29

- CHAP. VI. Whether the Kingdom of Francogallia was Hereditary or Elective; and the Manner of making its Kings. 38

- CHAP. VII. What Rule was observed concerning the Inheritance of the Deceased King, when he left more Children than one. 48

- CHAP. VIII. Of the Salick Law, and what Right Women had in the Kings, their Father's Inheritance. 54

- CHAP. IX. Of the Right of Wearing a large Head of Hair peculiar to the Royal Family. 58

- CHAP. X. The Form and Constitution of the Francogallican Government. 63

- CHAP. XI. Of the Sacred Authority of the Publick Council. 77

- CHAP. XII. Of the Kingly Officers, commonly called Mayors of the Palace. 85

- CHAP. XIII. Whether Pipin was created King by the Pope, or by the Authority of the Francogallican Council. 90

- CHAP. XIV. Of the Constable and Peers of France. 97

- CHAP. XV. Of the continued Authority and Power of the Sacred Council, during the Reign of the Carlovingian Family. 104

- CHAP. XVI. Of the Capevingian Race, and the Manner of its obtaining the Kingdom of Francogallia. 110

- CHAP. XVII. Of the uninterrupted Authority of the Publick Council, during the Capevingian Line. 114

- CHAP. XVIII. Of the Remarkable Authority of the Council against Lewis the Eleventh. 118

- CHAP. XIX. Of the Authority of the Assembly of the States, concerning the most important Affairs of Religion. 125

- CHAP. XX. Whether Women are not as much debarr'd by the Francogallican Law from the Administration, as from the Inheritance of the Kingdom. 128

- CHAP. XXI. Of the Juridical Parliaments in France. 138

Missing Advertisement (not coded).

Franco-Gallia

Translated by

The Author of the Account of DENMARK.

The BOOKSELLER TO THE READER. ↩

The following Translation of the Famous Hotoman's Franco-Gallia was written in the Year 1705, and first publish'd in the Year 1711. The Author was then at a great Distance from London, and the Publisher of his Work, for Reasons needless to repeat, did not think fit to print the Prefatory Discourse sent along with the Original. But this Piece being seasonable at all Times for the Perusal of Englishmen and more particularly at this Time, I wou'd no longer keep back from the Publick, what I more than conjecture will be acceptable to all true Lovers of their Country.

[i]

THE TRANSLATOR's PREFACE. ↩

Many Books and Papers have been publish'd since the late Revolution, tending to justify the Proceedings of the People of England at that happy juncture; by setting in a true Light our just Rights and Liberties, together with the solid Foundations of our Constitution: Which, in truth, is not ours only, but that of almost all Europe besides; so wisely restor'd and establish'd (if not introduced) by the Goths and Franks, whose Descendants we are.

These Books have as constantly had some things, called Answers, written to [ii] them, by Persons of different Sentiments; who certainly either never seriously consider'd, that the were thereby endeavouring to destroy their own Happiness, and overthrow her Majesty's Title to the Crown: or (if they knew what they did) presumed upon the Lenity of that Government they decry'd; which (were there no better Reason) ought to have recommended it to their Approbation, since it could patiently bear with such, as were doing all they could to undermine it.

Not to mention the Railing, Virulency, or personal false Reflections in many of those Answers, (which were always the Signs of a weak Cause, or a feeble Champion) some of them asserted the Divine Right of an Hereditary Monarch, and the Impiety of Resistance upon any Terms whatever, notwithstanding any Authorities to the contrary.

Others (and those the more judicious) deny'd positively, that sufficient Authorities could be produced to prove, that a free People have a just Power to defend themselves, by opposing their Prince, who endeavours to oppress and enslave them: And alledged, that whatever was said or done tending that way, proceeded from a Spirit of Rebellion, and Antimonarchical Principles.

[iii]

To confute, or convince this last Sort of Arguers (the first not being worthy to have Notice taken of them) I set about translating the Franco-Gallia of that most Learned and Judicious Civilian, Francis Hotoman; a Grave, Sincere and Unexceptionable Author, even in the Opinion of his Adversaries. This Book gives an Account of the Ancient Free State of above Three Parts in Four of Europe; and has of a long time appeared to me so convincing and instructive in those important Points he handles, that I could not be idle whilst it remain'd unknown, in a manner, to Englishmen: who, of all People living, have the greatest Reason and Need to be thoroughly instructed in what it contains; as having, on the one hand, the most to lose, and on the other, the least Sense of their Right, to that, which hitherto they seem (at least in a great measure) to have preserv'd.

It will be obvious to every Reader, that I have taken no great Pains to write elegantly. What I endeavour at, is as plain a Stile as possible, which on this Occasion I take to be the best: For since the Instruction of Mankind ought to be the principal Drift of all Writers (of History especially); whoever writes to the Capacity of most Readers, in my Opinion most fully answers the End.

[iv]

I am not ignorant, how tiresome and difficult a Piece of Work it is to translate, nor how little valued in the World. My Experience has convinced me, that 'tis more troublesome and teazing than to write and invent at once. The Idiom of the Language out of which one translates, runs so in the Head, that 'tis next to impossible not to fall frequently into it. And the more bald and incorrect the Stile of the Original is, the more shall that of the Translation be so too. Many of the Quotations in this Book are drawn from Priests, Monks, Friars, and Civil Lawyers, who minded more, in those barbarous Ages, the Substance than the Stile of their Writings: And I hope those Considerations may atone for several Faults, which might be found in my Share of this Work.

But I desire not to be misunderstood, as if (whilst I am craving Favour for my self) I were making any Apology for such a Number of mercenary Scribblers, Animadverters, and Translators, as pester us in this Age; who generally spoil the good Books which fall into their Hands, and hinder others from obliging the Publick, who otherwise would do it to greater Advantage.

I take this Author to be one of those few, that has had the good Luck to escape them; and I make use of this Occasion to [v] declare, that the chief Motive which induces me to send abroad this small Treatise, is a sincere desire of instructing the only Possessors of true Liberty in the World, what Right and Title that have to that Liberty; of what a great Value it is; what Misery follows the Loss of it; how easily, if Care be taken in time, it may be preserv'd: And if this either opens the Eyes, or confirms the honourable Resolutions of any of my worthy Countrymen, I have gained a glorious End; and done that in my Study, which I shou'd have promoted any other way, had I been called to it. I hope to die with the Comfort of believing, that Old England will continue to be a free Country, and know itself to be such; that my Friends, Relations and Children, with their Posterity, will inherit their Share of this inestimable Blessing, and that I have contributed my Part to it.

But there is one very great Discouragement under which both I, and all other Writers and Translators of Books tending to the acquiring or preserving the publick Liberty, do lie; and that is, the heavy Calumny thrown upon us, that we are all Commonwealth's-Men: Which (in the ordinary Meaning of the Word) amounts to Haters of Kingly Government; now without broad, malicious Insinuations, that we are no great Friends of the present.

[vi]

Indeed were the Laity of our Nation (as too many of our Clergy unhappily are) to be guided by the Sense of one of our Universities, solemnly and publickly declared by the burning of Twenty seven Propositions (some of them deserving that Censure, but others being the very Foundation of all our Civil Rights;) I, and many like me, would appear to be very much in the wrong. But since the Revolution in Eighty-eight, that we stand upon another and a better Bottom, tho no other than our own old one, 'tis time that our Notions should be suited to our Constitution. And truly, as Matters stand, I have often wondred, either how so many of our Gentlemen, educated under such Prejudices, shou'd retain any Sense at all of Liberty, for the hardest Lesson is to unlearn; St. Chrysostom. or how an Education so diametrically opposite to our Bill of Rights, shou'd be so long encouraged.

Methinks a Civil Test might be contrived, and prove very convenient to distinguish those that own the Revolution Principles, from such as Tooth and Nail oppose them; and at the same time do fatally propagate Doctrines, which lay too heavy a Load upon Christianity it self, and make us prove our own Executioners.

The Names of Whig and Tory will, I am afraid, last as long among us, as those [vii] of Guelf and Ghibelline did in Italy. I am sorry for it: but to some they become necessary for Distinction Sake; not so much for the Principles formerly adapted to each Name, as for particular and worse Reasons. For there has been such chopping and changing both of Names and Principles, that we scarce know who is who. I think it therefore necessary, in order to appear in my own Colours, to make a publick Profession of my Political Faith; not doubting but it may agree in several Particulars with that of many worthy Persons, who are as undeservedly aspers'd as I am.

My Notion of a Whig, I mean of a real Whig (for the Nominal are worse than any Sort of Men) is, That he is one who is exactly for keeping up to the Strictness of the true old Gothick Constitution, under the Three Estates of King (or Queen) Lords and Commons; the Legislature being seated in all Three together, the Executive entrusted with the first, but accountable to the whole Body of the People, in Case of Male Administration.

A true Whig is of Opinion, that the Executive Power has as just a Title to the Allegiance and Obedience of the Subject, according to the Rules of known Laws enacted by the Legislative, as the Subject has to Protection, Liberty and Property: And so on the contrary.

[viii]

A true Whig is not afraid of the Name of a Commonwealthsman, because so many foolish People, who know not what it means, run it down: The Anarchy and Confusion which these Nations fell into near Sixty Years ago, and which was falsly called a Commonwealth, frightning them out of the true Construction of the Word. But Queen Elizabeth, and many other of our best Princes, were not scrupulous of calling our Government a Commonwealth, even in their solemn Speeches to Parliament. And indeed if it be not one, I cannot tell by what Name properly to call it: For where in the very Frame of the Constitution, the Good of the Whole is taken care of by the Whole (as 'tis in our Case) the having a King or Queen at the Head of it, alters not the Case; and the softning of it by calling it a Limited Monarchy, seems a Kind of Contradiction in Terms, invented to please some weak and doubting Persons.

And because some of our Princes in this last Age, did their utmost Endeavour to destroy this Union and Harmony of the Three Estates, and to be arbitrary or independent, they ought to be looked upon as the Aggressors upon our Constitution.

This drove the other Two Estates (for the Sake of the publick Preservation) into the fatal Necessity of providing for themselves; [ix] and when once the Wheel was set a running, 'twas not in the Power of Man to stop it just where it ought to have stopp'd. This is so ordinary in all violent Motions, whether mechanick or political, that no body can wonder at it.

But no wise Men approved of the ill Effects of those violent Motions either way, cou'd they have help'd them. Yet it must be owned they have (as often as used, thro an extraordinary Piece of good Fortune) brought us back to our old Constitution again, which else had been lost; for there are numberless Instances in History of a Downfal from a State of Liberty to a Tyranny, but very few of a Recovery of Liberty from Tyranny, if this last have had any Length of Time to fix it self and take Root.

Let all such, who either thro Interest or Ignorance are Adorers of absolute Monarchs, say what they please; an English Whig can never be so unjust to his Country, and to right Reason, as not to be of Opinion, that in all Civil Commotions, which Side soever is the wrongful Aggressor, is accountable for all the evil Consequences: And thro the Course of his reading (tho my Lord Clarendon's Books be thrown into the Heap) he finds it very difficult to observe, that ever the People of England took up Arms against their Prince, but when constrain'd [x] to it by a necessary Care of their Liberties and true Constitution.

'Tis certainly as much a Treason and Rebellion against this Constitution, and the known Laws, in a Prince to endeavor to break thro them, as 'tis in the People to rise against him, whilst he keeps within their Bounds, and does his Duty. Our Constitution is a Government of Laws, not of Persons. Allegiance and Protection are Obligations that cannot subsist separately; when one fails, the other falls of Course. The true Etymology of the word Loyalty (which has been so strangely wrested in the late Reigns) is an entire Obedience to the Prince in all his Commands according to Law; that is, to the Laws themselves, to which we owe both an active and passive Obedience.

By the old and true Maxim, that the King can do no Wrong, nobody is so foolish as to conclude, that he has not Strength to murder, to offer Violence to Women, or Power enough to dispossess a Man wrongfully of his Estate, or that whatever he does (how wicked soever) is just: but the Meaning is, he has no lawful Power to do such Things; and our Constitution considers no Power as irresistible, but what is lawful.

And since Religion is become a great and universal Concern, and drawn into our [xi] Government, as it affects every single Man's Conscience; tho my private Opinion, they ought not to be mingled, nor to have any thing to do with each other; (I do not speak of our Church Polity, which is a Part of our State, and dependent upon it) some account must be given of that Matter.

Whiggism is not circumscrib'd and confin'd to any one or two of the Religions now profess'd in the World, but diffuses it self among all. We have known Jews, Turks, nay, some Papists, (which I own to be a great Rarity) very great Lovers of the Constitution and Liberty; and were there rational Grounds to expect, that any Numbers of them cou'd be so, I shou'd be against using Severities and Distinctions upon Account of Religion. For a Papist is not dangerous, nor ought to be ill us'd by any body, because he prays to Saints, believes Purgatory, or the real Presence in the Eucharist, and pays Divine Worship to an Image or Picture (which are the common Topicks of our Writers of Controversy against the Papists;) but because Popery sets up a foreign Jurisdiction paramount to our Laws. So that a real Papist can neither be a true Governor of a Protestant Country, nor a true Subject, and besides, is the most Priest-Ridden Creature in the World: and (when uppermost) can bear with no body [xii] that differs from him in Opinion; little considering, that whosoever is against Liberty of Mind, is, in effect, against Liberty of Body too. And therefore all Penal Acts of Parliament for Opinions purely religious, which have no Influence on the State, are so many Encroachments upon Liberty, whilst those which restrain Vice and Injustice are against Licentiousness.

I profess my self to have always been a Member of the Church of England and am for supporting it in all its Honours, Privileges and Revenues: but as a Christian and a Whig, I must have Charity for those that differ from me in religious Opinions, whether Pagans, Turks, Jews, Papists, Quakers, Socinians, Presbyterians, or others. I look upon Bigotry to have always been the very Bane of human Society, and the Offspring of Interest and Ignorance, which has occasion'd most of the great Mischiefs that have afflicted Mankind. We ought no more to expect to be all of one Opinion, as to the Worship of the Deity, than to be all of one Colour or Stature. To stretch or narrow any Man's Conscience to the Standard of our own, is no less a Piece of Cruelty than that of Procrustes the Tyrant of Attica, who used to fit his Guests to the Length of his own Iron Bedsted, either by cutting them shorter, or racking them longer. What [xiii] just Reason can I have to be angry with, to endeavour to curb the natural Liberty, or to retrench the Civil Advantages of an honest Man (who follows the golden Rule, of doing to others, as he wou'd have others do to him, and is willing and able to serve the Publick) only because he thinks his Way to Heaven surer or shorter than mine? No body can tell which of us is mistaken, till the Day of Judgment, or whether any of us be so (for there may be different Ways to the same End, and I am not for circumscribing God Almighty's Mercy:) This I am sure of, one shall meet with the same Positiveness in Opinion, in some of the Priests of all these Sects; The same Want of Charity, engrossing Heaven by way of Monopoly to their own Corporation, and managing it by a joint Stock, exclusive of all others (as pernicious in Divinity as in trade, and perhaps more) The same Pretences to Miracles, Martyrs, Inspirations, Merits, Mortifications, Revelations, Austerity, Antiquity, &c. (as all Persons conversant with History, or that travel, know to be true) and this cui bono? I think it the Honour of the Reformed Part of the Christian Profession, and the Church of England in particular, that it pretends to fewer of these unusual and extraordinary Things, than any other Religion we know of in the World; being [xiv] convinced, that these are not the distinguishing Marks of the Truth of any Religion (I mean, the assuming obstinate Pretences to them are not;) and it were not amiss, if we farther enlarg'd our Charity, when we can do it with Safety, or Advantage to the State.

Let us but consider, how hard and how impolitick it is to condemn all People, but such as think of the Divinity just as we do. May not the Tables of Persecution be turn'd upon us? A Mahometan in Turky is in the right, and I (if I carry my own Religion thither) am in the Wrong. They will have it so. If the Mahometan comes with me to Christendom, I am in the right, and he in the wrong; and hate each other heartily for differing in Speculations, which ought to have no Influence on Moral Honesty. Nay, the Mahometan is the more charitable of the two, and does not push his Zeal so far; for the Christians have been more cruel and severe in this Point than all the World besides. Surely Reprizals may be made upon us; as Calvin burnt Servetus at Geneva, Queen Mary burnt Cranmer at London. I am sorry I cannot readily find a more exact Parallel. The Sword cuts with both Edges. Why, I pray you, may we not all be Fellow-Citizens of the World? And provided it be not the Principle of one or more [xv] Religions to extirpate all others, and to turn Persecutors when they get Power (for such are not to be endured;) I say, why shou'd we offer to hinder any Man from doing with his own Soul what he thinks fitting? Why shou'd we not make use of his Body, Estate, and Understanding, for the publick Good? Let a Man's Life, Substance, and Liberty be under the Protection of the Laws; and I dare answer for him (whilst his Stake is among us) he will never be in a different Interest, nor willing to quit this Protection, or to exchange it for Poverty, Slavery, and Misery.

The thriving of any one single Person by honest Means, is the Thriving of the Commonwealth wherein he resides. And in what Place soever of the World such Encouragement is given, as that in it one may securely and peaceably enjoy Property and Liberty both of Mind and Body; 'tis impossible but that Place must flourish in Riches and in People, which are the truest Riches of any Country.

But as, on the one hand, a true Whig thinks that all Opinions purely spiritual and notional ought to be indulg'd; so on the other, he is for severely punishing all Immoralities, Breach of Laws, Violence and Injustice. A Minister's Tythes are as much his Right, as any Layman's Estate can be his; and no Pretence of Religion or Conscience can warrant the substracting of them, [xvi] whilst the Law is in Being which makes them payable: For a Whig is far from the Opinion, that they are due by any other Title. It wou'd make a Man's Ears tingle, to hear the Divine Right insisted upon for any human Institutions; and to find God Almighty brought in as a Principal there, where there is no Necessity for it. To affirm, that Monarchy, Episcopacy, Synods, Tythes, the Hereditary Succession to the Crown, &c. are Jure Divino; is to cram them down a Man's Throat; and tell him in plain Terms, that he must submit to any of them under all Inconveniencies, whether the Laws of his Country are for it or against it. Every Whig owns Submission to Government to be an Ordinance of God. Submit your selves to every Ordinance of Man, for the Lord's Sake, says the Apostle. Where (by the way) pray take notice, he calls them Ordinances of Man; and gives you the true Notion, how far any thing can be said to be Jure Divino: which is far short of what your high-flown Assertors of the Jus Divinum wou'd carry it, and proves as strongly for a Republican Government as a Monarchical; tho' in truth it affects neither, where the very Ends of Government are destroyed.

A right Whig looks upon frequent Parliaments as such a fundamental Part of the Constitution, that even no Parliament can [xvii] part with this Right. High Whiggism is for Annual Parliaments, and Low Whiggism for Triennial, with annual Meetings. I leave it to every Man's Judgment, which of these wou'd be the truest Representative; wou'd soonest ease the House of that Number of Members that have Offices and Employments, or take Pensions from the Court; is least liable to Corruption; wou'd prevent exorbitant Expence, and soonest destroy the pernicious Practice of drinking and bribing for Elections, or is most conformable to ancient Custom. The Law that lately pass'd with so much Struggle for Triennial Parliaments shall content me, till the Legislative shall think fit to make them Annual.

But methinks (and this I write with great Submission and Deference) that (since the passing that Act) it seems inconsistent with the Reason of the thing, and preposterous, for the first Parliament after any Prince's Accession to the Crown, to give the publick Revenue arising by Taxes, for a longer time than that Parliament's own Duration. I cannot see why the Members of the first Parliament shou'd (as the Case now stands) engross to themselves all the Power of giving, as well as all the Merit and Rewards due to such a Gift: and why succeeding Parliaments shou'd not, in their turn, have it in their [xviii] Power to oblige the Prince, or to streighten him, if they saw Occasion; and pare his Nails, if they were convinced he made ill Use of such a Revenue. I am sure we have had Instances of this Kind; and a wise Body of Senators ought always to provide against the worst that might happen. The Honey-Moon of Government is a dangerous Season; the Rights and Liberties of the People run a greater Risk at that time, thro their own Representatives Compliments and Compliances, than they are ever likely to do during that Reign: and 'tis safer to break this Practice, when we have the Prospect of a good and gracious Prince upon the Throne, than when we have an inflexible Person, who thinks every Offer an Affront, which comes not up to the Height of what his Predecessor had, without considering whether it were well or ill done at first.

The Revenues of our Kings, for many Ages, arose out of their Crown-Lands; Taxes on the Subject were raised only for publick Exigencies. But since we have turn'd the Stream, and been so free of Revenues for Life, arising from Impositions and Taxes, we have given Occasion to our Princes to dispose of their Crown-Lands; and depend for Maintenance of their Families on such a Sort of Income, as is thought unjust and ungodly in most Parts of the [xix] World, but in Christendom: for many of the arbitrary Eastern Monarchs think so, and will not eat the Produce of such a Revenue. Now since Matters are brought to this pass, 'tis plain that our Princes must subsist suitable to their high State and Condition, in the best manner we are able to provide for them. And whilst the Calling and Duration of Parliaments was precarious, it might indeed be an Act of Imprudence, tho not of Injustice, for any one Parliament to settle such a Sort of Revenue for Life on the Prince: But at present, when all the World knows the utmost Extent of a Parliament's possible Duration, it seems disagreeable to Reason, and an Encroachment upon the Right of succeeding Parliaments (for the future) for any one Parliament to do that which another cannot undo, or has not Power to do in its turn.

An Old Whig is for chusing such Sort of Representatives to serve in Parliament, as have Estates in the Kingdom; and those not fleeting ones, which may be sent beyond Sea by Bills of Exchange by every Pacquet-Boat, but fix'd and permanent. To which end, every Merchant, Banker, or other money'd Man, who is ambitious of serving his Country as a Senator, shou'd have also a competent, visible Land Estate, as a Pledge to his Electors that he intends to abide by them, and has the same Interest [xx] with theirs in the publick Taxes, Gains and Losses. I have heard and weigh'd the Arguments of those who, in Opposition to this, urged the Unfitness of such, whose Lands were engaged in Debts and Mortgages, to serve in Parliament, in comparison with the mony'd Man who had no Land: But those Arguments never convinced me.

No Man can be a sincere Lover of Liberty, that is not for increasing and communicating that Blessing to all People; and therefore the giving or restoring it not only to our Brethren of Scotland and Ireland, but even to France it self (were it in our Power) is one of the principal Articles of Whiggism. The Ease and Advantage which wou'd be gain'd by uniting our own Three Kingdoms upon equal Terms (for upon unequal it wou'd be no Union) is so visible, that if we had not the Example of those Masters of the World, the Romans, before our Eyes, one wou'd wonder that our own Experience (in the Instance of uniting Wales to England) shou'd not convince us, that altho both Sides wou'd incredibly gain by it, yet the rich and opulent Country, to which such an Addition is made, wou'd be the greater Gainer. 'Tis so much more desirable and secure to govern by Love and common Interest, than by Force; to expect Comfort and Assistance, in Times of Danger, from our next Neighbours, than to find [xxi] them at such a time a heavy Clog upon the Wheels of our Government, and be in dread lest they should take that Occasion to shake off an uneasy Yoak: or to have as much need of entertaining a standing Army against our Brethren, as against our known and inveterate Enemies; that certainly whoever can oppose so publick and apparent Good, must be esteem'd either ignorant to a strange Degree, or to have other Designs in View, which he wou'd willingly have brought to Light.

I look upon her Majesty's asserting the Liberties and Privileges of the Free Cities in Germany, an Action which will shine in History as bright (at least) as her giving away her first Fruits and Tenths: To the Merit of which last, some have assumingly enough ascribed all the Successes she has hitherto been blessed with; as if one Set of Men were the peculiar Care of Providence and all others (even Kings and Princes) were no otherwise fit to be considered by God Almighty, or Posterity, than according to their Kindness to them. But it has been generally represented so, where Priests are the Historians. From the first Kings in the World down to these Days, many Instances might be given of very wicked Princes, who have been extravagantly commended; and many excellent ones, whose Memories lie overwhelmed with Loads of Curses and [xxii] Calumny, just as they proved Favourers or Discountenancers of High-Church, without regard to their other Virtues or Vices: for High-Church is to be found in all Religions and Sects, from the Pagan down to the Presbyterian; and is equally detrimental in every one of them.

A Genuine Whig is for promoting a general Naturalization, upon the firm Belief, that whoever comes to be incorporated into us, feels his Share of all our Advantages and Disadvantages, and consequently can have no Interest but that of the Publick; to which he will always be a Support to the best of his Power, by his Person, Substance and Advice. And if it be a Truth (which few will make a Doubt of) that we are not one third Part peopled (though we are better so in Proportion than any other Part of Europe, Holland excepted) and that our Stock of Men decreases daily thro our Wars, Plantations, and Sea-Voyages; that the ordinary Course of Propagation (even in Times of continued Peace and Health) cou'd not in many Ages supply us with the Numbers we want; that the Security of Civil and Religious Liberty, and of Property, which thro God's great Mercy is firmly establish'd among us, will invite new Comers as fast as we can entertain them; that most of the rest of the World groans under the Weight of Tyranny, [xxiii] which will cause all that have Substance, and a Sense of Honour and Liberty, to fly to Places of Shelter; which consequently would thoroughly people us with useful and profitable Hands in a few Years. What should hinder us from an Act of General Naturalization? Especially when we consider, that no private Acts of that Kind are refused; but the Expence is so great, that few attempt to procure them, and the Benefit which the Publick receives thereby is inconsiderable.

Experience has shown us the Folly and Falsity of those plausible Insinuations, that such a Naturalization would take the Bread out of Englishmen's Mouths. We are convinced, that the greater Number of Workmen of one Trade there is in any Town, the more does that Town thrive; the greater will be the Demand of the Manufacture, and the Vent to foreign Parts, and the quicker Circulation of the Coin. The Consumption of the Produce both of Land and Industry increases visibly in Towns full of People; nay, the more shall every particular industrious Person thrive in such a Place; tho indeed Drones and Idlers will not find their Account, who wou'd fain support their own and their Families superfluous Expences at their Neighbour's Cost; who make one or two Day's Labour provide for four Days Extravagancies. And this is the [xxiv] common Calamity of most of our Corporation Towns, whose Inhabitants do all they can to discourage Plenty, Industry and Population; and will not admit of Strangers but upon too hard Terms, thro the false Notion, that they themselves, their Children and Apprentices, have the only Right to squander their Town's Revenue, and to get, at their own Rates, all that is to be gotten within their Precincts, or in the Neighbourhood. And therefore such Towns (through the Mischief arising by Combinations and By-Laws) are at best at a Stand; very few in a thriving Condition (and those are where the By-Laws are least restrictive) but most throughout England fall to visible Decay, whilst new Villages not incorporated, or more liberal of their Privileges, grow up in their stead; till, in Process of Time, the first Sort will become almost as desolate as Old Sarum, and will as well deserve to lose their Right of sending Representatives to Parliament. For certainly a Waste or a Desert has no Right to be represented, nor by our original Constitution was ever intended to be: yet I would by no means have those Deputies lost to the Commons, but transferr'd to wiser, more industrious, and better peopled Places, worthy (thro their Numbers and Wealth) of being represented.

[xxv]

A Whig is against the raising or keeping up a Standing Army in Time of Peace: but with this Distinction, that if at any time an Army (tho even in Time of Peace) shou'd be necessary to the Support of this very Maxim, a Whig is not for being too hasty to destroy that which is to be the Defender of his Liberty. I desire to be well understood. Suppose then, that Persons, whose known Principle and Practice it has been (during the Attempts for arbitrary Government) to plead for and promote such an Army in Time of Peace, as wou'd be subservient to the Will of a Tyrant, and contribute towards the enslaving the Nation; shou'd, under a legal Government (yet before the Ferment of the People was appeas'd) cry down a Standing Army in Time of Peace: I shou'd shrewdly suspect, that the Principles of such Persons are not changed, but that either they like not the Hands that Army is in, or the Cause which it espouses; and look upon it as an Obstruction to another Sort of Army, which they shou'd like even in Time of Peace. I say then, that altho the Maxim in general be certainly true, yet a Whig (without the just Imputation of having deserted his Principles) may be for the keeping up such a Standing Army even in Time of Peace, till the Nation have recover'd its Wits again, and chuses Representatives who are [xxvi] against Tyranny in any Hands whatsoever; till the Enemies of our Liberties want the Power of raising another Army of quite different Sentiments: for till that time, a Whiggish Army is the Guardian of our Liberties, and secures to us the Power of disbanding its self, and prevents the raising of another of a different Kidney. As soon as this is done effectually, by my Consent, no such thing as a mercenary Soldier should subsist in England. And therefore The arming and training of all the Freeholders of England, as it is our undoubted ancient Constitution, and consequently our Right; so it is the Opinion of most Whigs, that it ought to be put in Practice. This wou'd put us out of all Fear of foreign Invasions, or disappoint any such when attempted: This wou'd soon take away the Necessity of maintaining Standing Armies of Mercenaries in Time of Peace: This wou'd render us a hundred times more formidable to our Neighbours than we are; and secure effectually our Liberties against any King that shou'd have a mind to invade them at home, which perhaps was the Reason some of our late Kings were so averse to it: And whereas, as the Case now stands, Ten Thousand disciplin'd Soldiers (once landed) might march without considerable Opposition from one End of England to the other; were our Militia well [xxvii] regulated, and Fire-Arms substituted in the Place of Bills, Bows, and Arrows (the Weapons in Use when our training Laws were in their Vigor, and for which our Laws are yet in Force) we need not fear a Hundred Thousand Enemies, were it possible to land so many among us. At every Mile's End, at every River and Pass, the Enemy wou'd meet with fresh Armies, consisting of Men as well skill'd in military Discipline as themselves; and more resolv'd to fight, because they do it for Property: And the farther such an Enemy advanced into the Country, the stronger and more resolved he wou'd find us; as Hanibal did the Romans, when he encamped under the Walls of Rome, even after such a Defeat as that at Cannæ. And why? Because they were all train'd Soldiers, they were all Freemen that fought pro aris & focis: and scorn'd to trust the Preservation of their Lives and Fortunes to Mercenaries or Slaves, tho never so able-body'd: They thought Weapons became not the Hands of such as had nothing to lose, and upon that Account were unfit Defenders of their Masters Properties; so that they never tried the Experiment but in the utmost Extremity.

That this is not only practicable but easy, the modern Examples of the Swissers and Swedes is an undeniable Indication. [xxviii] Englishmen have as much Courage, as great Strength of Body, and Capacity of Mind, as any People in the Universe: And if our late Monarchs had the enervating their free Subjects in View, that they might give a Reputation to Mercenaries, who depended only on the Prince for their Pay (as 'tis plain they had) I know no Reason why their Example shou'd be followed in the Days of Liberty, when there is no such Prospect. The Preservation of the Game is but a very slender Pretence for omitting it. I hope no wise Man will put a Hare or a Partridge in Balance with the Safety and Liberties of Englishmen; tho after all, 'tis well known to Sportsmen, that Dogs, Snares, Nets, and such silent Methods as are daily put in Practice, destroy the Game ten times more than shooting with Guns.

If the restoring us to our Old Constitution in this Instance were ever necessary, 'tis more eminently so at this time, when our next Neighbours of Scotland are by Law armed just in the manner we desire to be, and the Union between both Kingdoms not perfected. For the Militia, upon the Foot it now stands, will be of little Use to us: 'tis generally compos'd of Servants, and those not always the same, consequently not well train'd; rather such as wink with both Eyes at their own firing a Musket, [xxix] and scarce know how to keep it clean, or to charge it aright. It consists of People whose Reputation (especially the Officers) has been industriously diminished, and their Persons, as well as their Employment, rendred contemptible on purpose to enhance the Value of those that serve for Pay; insomuch that few Gentlemen of Quality will now a-days debase themselves so much, as to accept of a Company, or a Regiment in the Militia. But for all this, I can never be persuaded that a Red Coat, and Three Pence a Day, infuses more Courage into the poor Swaggering Idler, than the having a Wife and Children, and an Estate to fight for, with good wholsome Fare in his Kitchen, wou'd into a Free-born Subject, provided the Freeman were as well armed and trained as the Mercenary.

I wou'd not have the Officers and Soldiers of our most Brave and Honest Army to mistake me. I am not arguing against them; for I am convinced, as long as there is Work to do abroad, 'tis they (and not our home dwelling Freeholders) are most proper for it. Our War must now be an Offensive War; and what I am pleading for, concerns only the bare Defensive Part. Most of our present Generals and Officers are fill'd with the true Sprit of Liberty (a most rare thing) which demonstrates [xxx] the Felicity of her Majesty's Reign, and her standing upon a true Bottom, beyond any other Instance that can be given; insomuch, that considering how great and happy we have been under the Government of Queens, I have sometimes doubted, whether an Anti-Salick Law wou'd be to our Disadvantage.

Most of these Officers do expect, nay (so true do I take them to be to their Country's Interest) do wish, whenever it shall please God to send us such a Peace as may be relied upon both at home and abroad, to return to the State of peaceable Citizens again; but 'tis fit they should do so, with such ample Rewards for their Blood and Labours, as shall entirely satisfy them. And when they, or the Survivors of them, shall return full of Honour and Scars home to their Relations, after the Fatigues of so glorious a Service to their Country are ended; 'tis their Country's Duty to make them easy, without laying a Necessity upon them of striving for the Continuance of an Army to avoid starving. The Romans used to content them by a Distribution of their Enemies Lands; and I think their Example so good in every thing, that we could hardly propose a better. Oliver Cromwell did the like in Ireland, to which we owe that Kingdom's [xxxi] being a Protestant Kingdom at this Day, and its continuing subject to the Crown of England; but if it be too late to think of this Method now, some other must be found out by the Wisdom of Parliament, which shall fully answer the End.

These Officers and Soldiers thus settled and reduced to a Civil State, wou'd, in a great measure, compose that invincible Militia I am now forecasting; and by reason of their Skill in military Affairs, wou'd deserve the principal Posts and Commands in their respective Counties: With this advantageous Change of their Condition, that whereas formerly they fought for their Country only as Soldiers of Fortune, now they shou'd defend it as wise and valiant Citizens, as Proprietors of the Estates they fight for; and this will gain them the entire Trust and Confidence of all the good People of England, who, whenever they come to know their own Minds, do heartily hate Slavery. The Manner and Times of assembling, with several other necessary Regulations, are only proper for the Legislative to fix and determine.

A right Whig lays no Stress upon the Illegitimacy of the pretended Prince of Wales; he goes upon another Principle than they, who carry the Right of Succession so far, as (upon that Score), to undo all [xxxii] Mankind. He thinks no Prince fit to govern, whose Principle it must be to ruin the Constitution, as soon as he can acquire unjust Power to do so. He judges it Nonsense for one to be the Head of a Church, or Defender of a Faith, who thinks himself bound in Duty to overthrow it. He never endeavours to justify his taking the Oaths to this Government, or to quiet his Conscience, by supposing the young Gentleman at St. Germains unlawfully begotten; since, 'tis certain, that according to our Law he cannot be looked upon as such. He cannot satisfy himself with any of the foolish Distinctions trump'd up of late Years to reconcile base Interest with a Show of Religion; but deals upon the Square, and plainly owns to the World, that he is not influenc'd by any particular Spleen: but that the Exercise of an Arbitrary, Illegal Power in the Nation, so as to undermine the Constitution, wou'd incapacitate either King James, King William, or any other, from being his King, whenever the Publick has a Power to hinder it.

As a necessary Consequence of this Opinion, a Whig must be against punishing the Iniquity of the Fathers upon the Children, as we do (not only to the Third and Fourth Generation, but) for ever: since our gracious God has declared, that he will no [xxxiii] more pursue such severe Methods in his Justice, but that the Soul that sinneth it shall die. 'Tis very unreasonable, that frail Man, who has so often need of Mercy, shou'd pretend to exercise higher Severities upon his Fellow-Creatures, than that Fountain of Justice on his most wicked revolting Slaves. To corrupt the Blood of a whole Family, and send all the Offspring a begging after the Father's Head is taken off, seems a strange Piece of Severity, fit to be redressed in Parliament; especially when we come to consider, for what Crime this has been commonly done. When Subjects take Arms against their Prince, if their Attempt succeeds, 'tis a Revolution; if not, 'tis call'd a Rebellion: 'tis seldom consider'd, whether the first Motives be just or unjust. Now is it not enough, in such Cases, for the prevailing Party to hang or behead the Offenders, if they can catch them, without extending the Punishment to innocent Persons for all Generations to come?

The Sense of this made the late Bill of Treasons (tho it reach'd not so far as many wou'd have had it) a Favourite of the Old Whigs; they thought it a very desirable one whenever it cou'd be compass'd, and perhaps if not at that very Juncture, wou'd not have been obtained all: 'twas necessary for Two different Sorts of People to [xxxiv] unite in this, in order for a Majority, whose Weight shou'd be sufficient to enforce it. And I think some Whigs were very unjustly reproach'd by their Brethren, as if by voting for this Bill, they wilfully exposed the late King's Person to the wicked Designs of his Enemies.

Lastly, The supporting of Parliamentary Credit, promoting of all publick Buildings and Highways, the making all Rivers Navigable that are capable of it, employing the Poor, suppressing Idlers, restraining Monopolies upon Trade, maintaining the liberty of the Press, the just paying and encouraging of all in the publick Service, especially that best and usefullest Sort of People the Seamen: These (joined to a firm Opinion, that we ought not to hearken to any Terms of Peace with the French King, till it be quite out of his Power to hurt us, but rather to dye in Defence of our own and the Liberties of Europe) are all of them Articles of my Whiggish Belief, and I hope none of them are heterodox. And if all these together amount to a Commonwealthsman, I shall never be asham'd of the Name, tho given with a Design of fixing a Reproach upon me, and such as think as I do.

Many People complain of the Poverty of the Nation, and the Weight of the Taxes. [xxxv] Some do this without any ill Design, but others hope thereby to become popular; and at the same time to enforce a Peace with France, before that Kingdom be reduced to too low a Pitch: fearing, lest that King shou'd be disabled to accomplish their Scheme of bringing in the Pretender, and assisting him.

Now altho 'tis acknowledg'd, that the Taxes lye very heavy, and Money grows scarce; yet let the Importance of our War be considered, together with the Obstinacy, Perfidy, and Strength of our Enemy, can we possibly carry on such a diffusive War without Money in Proportion? Are the Queen's Subjects more burden'd to maintain the publick Liberty, than the French King's are to confirm their own Slavery? Not so much by three Parts in four, God be prais'd: Besides, no true Englishman will grudge to pay Taxes whilst he has a Penny in his Purse, as long as he sees the Publick Money well laid out for the great Ends for which 'tis given. And to the Honour of the Queen and her Ministers it may be justly said, That since England was a Nation, never was the publick Money more frugally managed, or more fitly apply'd. This is a further Mortification to those Gentlemen, who have Designs in View which they dare not own: For whatever [xxxvi] may be, the plausible and specious Reasons they give in publick, when they exclaim against the Ministry; the hidden and true one is, that thro the present prudent Administration, their so hopefully-laid Project is in Danger of being blown quite up; and they begin to despair that they shall bring in King James the Third by the Means of Queen Anne, as I verily believe they once had the Vanity to imagine.

[1]

A Short EXTRACT OF THE LIFE OF Francis Hotoman, ↩

Taken out of Monsieur Bayle's Hist. Dict. and other Authors.

FRANCIS HOTOMAN (one of the most learned Lawyers of that Age) was Born at Paris the 23d of August, 1524. His Family was an Ancient and Noble one, originally of Breslaw, the Capital of Silesia. Lambert Hotoman, his Grandfather, bore Arms in the Service of Lewis the 11th of France, and married a rich Heiress at Paris, by whom he had 18 Children; the Eldest of which (John Hotoman) had so plentiful an Estate, that he laid down the Ransom-Money for King Francis the First, taken at the Battel of Pavia: Summo galliæ bono, summâ cum suâ laude, says Neveletus,[2] Peter Hotoman his 18th Child, and Maistre des Eaux & Forrests. Master of the Waters and Forests of France (afterwards a Counsellor in the Parliament of Paris) was Father to Francis, the Author of this Book. He sent his Son, at 15 Years of Age, to Orleans to study the Common Law; which he did with so great Applause, that at Three Years End he merited the Degree of Doctor. His Father designing to surrender to him his Place of Counsellor of Parliament, sent for him home: But the young Gentleman was soon tired with the Chicane of the Bar, and plung'd himself deep in the Studies of Les belles Lettres. Humanity and the Roman Laws; for which he had a wonderful Inclination. He happen'd to be a frequent Spectator of the Protestants Sufferings, who, about that Time, had their Tongues cut out, were otherwise tormented, and burnt for their Religion. This made him curious to dive into those Opinions, which inspired so much Constancy, Resignation and Contempt of Death; which brought him by degrees to a liking of them, so that he turn'd Protestant. And this put him in Disgrace with his father, who thereupon disinherited him; which forced him at last to quit France, and to retire to Lausanne in Swisserland by Calvin's and Beza's Advice; where his great Merit and Piety promoted him to the Humanity-Professor's Chair, which he accepted of for a Livelihood, having no Subsistance from his Father. There he married a young French Lady, who had fled her Country upon the Score of Religion: He afterwards remov'd to Strasburg, where he also had a Professor's Chair. The Fame of his great Worth was so blown about, that he was invited by all the great Princes to their several Countries, particularly by [3] the Landgrave of Hesse, the Duke of Prussia, and the King of Navarre; and he actually went to this last about the Beginning of the Troubles. Twice he was sent as Ambassador from the Princes of the Blood of France, and the Queen-Mother, to demand Assistance of the Emperor Ferdinand: The Speech that he made at the Diet of Francfort is still extant. Afterwards he returned to Strasburg; but Jean de Monluc, the Bishop of Valence, over-persuaded him to accept of the Professorship of Civil Law at Valence; of which he acquitted himself so well, that he very much heighten'd the Reputation of that University. Here he received two Invitations from Margaret Dutchess of Berry, and Sister to Henry the Second of France, and accepted a Professor's Chair at Bourges; but continued in it no longer than five Months, by reason of the intervening Troubles. Afterwards he returned to it, and was there at the time of the great Parisian Massacre, having much-a-do to escape with his Life; but having once got out of France (with a firm Resolution never to return thither again) he took Sanctuary in the House of Calvin at Geneva, and publish'd Books against the Persecution, so full of Spirit and good Reasoning, that the Heads of the contrary Party made him great Offers in case he wou'd forbear Writing against them; but he refused them all, and said, The Truth shou'd never be betray'd or forsaken by him. Neveletus says, "That his Reply to those that wou'd have tempted him, was this: Nunquam sibi propugnatam causam quæ iniqua esset: Nunquam quæ jure & legibus niteretur desertam præmiorum spe vel metu periculi."—He afterwards went to Basel in Swisserland, and from thence (being [4] driven away by the Plague) to Mountbelliard, where he buried his Wife. He returned then to Basel (after having refused a Professor's Chair at Leyden) and there he died of a Dropsy in the 65th Year of his Age, the 12th of February, 1590.

He writ a great many learned Books, which were all of them in great Esteem; and among them an excellent Book de Consolatione. His Francogallia was his own Favourite; tho' blamed by several others, who were of the contrary Opinion: Yet even these who wrote against him do unanimously agree, that he had a World of Learning, and a profound Erudition. He had a thorough Knowledge of the Civil Law, which he managed with all the Eloquence imaginable; and was, without dispute, one of the ablest Civilians that France had ever produced: This is Thuanus and Barthius's Testimony of him. Mr. Bayle indeed passes his Censure of this Work in the Text of his Dictionary, in these Words: "Sa Francogallia dont il faisoit grand etat est celuy de tous ses ecrits que l'on aprouve le moins:"—and in his Commentary adds, "C'est un Ouvrage recommendable du costè de l'Erudition; mais tres indigne d'un jurisconsulte Francois, si l'on en croit mesme plusieurs Protestants." I wou'd not do any Injury to so great a Man as Monsieur Bayle; but every one that is acquainted with his Character, knows that he is more a Friend to Tyranny and Tyrants, than seems to be consistent with so free a Spirit. He has been extremely ill used, which sowres him to such a degree, that it even perverts his Judgment in some measure; and he seems resolved to be against Monsieur Jurieu, and that Party, in every thing, right or wrong. Whoever reads his Works, may trace throughout all Parts of [5] them this Disposition of Mind, and see what sticks most at his Heart. So that he not only loses no Occasion, but often forces one where it seems improper and unseasonable, to vent his Resentments upon his Enemies; who surely did themselves a great deal more wrong in making him so, than they did him. 'Tis too true, that they did all they cou'd to starve him; and this great Man was forced to write in haste for Bread; which has been the Cause that some of his Works are shorter than he design'd them; and consequently, that the World is deprived of so much Benefit, as otherwise it might have reap'd from his prodigious Learning, and Force of Judgment. One may see by the first Volume of his Dictionary, which goes through but two Letters of the Alphabet, that he forecasted to make that Work three times as large as it is, cou'd he have waited for the Printer's Money so long as was requisite to the finishing it according to his first Design. Thus much I thought fit to say, in order to abate the Edge of what he seems to speak hardly of the Francogallia; tho' in several other Places he makes my Author amends: And one may without scruple believe him, when he commends a Man, whose Opinion he condemns. For this is the Character he gives of this Work: "C'est au fond un bel Ouvrage, bien ecrit, & bien rempli d'erudition: Et d'autant plus incommode au partie contraire que l'Auteur se contente de citer des faits." Can any thing in the World be a greater Commendation of a Work of this Nature, than to say it contains only pure Matter of Fact? Now if this be so, Monsieur Bayle wou'd do well to tell us what he means by those Words, Tres indigne d'un jurisconsulte Francois. Whether a French [6] Civilian be debarr'd telling of Truth (when that Truth exposes Tyranny) more than a Civilian of any other Nation? This agrees, in some measure, with Monsieur Teissier's Judgment of the Francogallia, and shews, that Monsieur Bayle, and Monsieur Teissier and Bongars, were Bons Francois in one and the same Sense. "Son Livre intitulè, Francogallia, luy attira AVEC RAISON (and this he puts in great Letters) les blame des bons Francois. For (says he) therein he endeavours to prove, That France, the most flourishing Kingdom in Christendom, is not successive, like the Estates of particular Persons; but that anciently the Kings came to the Crown by the Choice and Suffrages of the Nobility and People; insomuch, that as in former Times the Power and Authority of Electing their Kings belonged to the Estates of the Kingdom, so likewise did the Right of Deposing their Princes from their Government. And hereupon he quotes the Examples of Philip de Valois, of King John, Charles the Fifth, and Charles the Sixth, and Lewis the Eleventh: But what he principally insists on, is to show, That as from Times Immemorial, the French judg'd Women incapable of Governing; So likewise ought they to be debarr'd from all Administration of the Publick Affairs."

This is Mr. Boyle's Quotation of Teissier, by which it appears how far Hotoman ought to be blamed by all true Frenchmen, AVEC RAISON. But provided that Hotoman proves irrefragably all that he says (as not only Monsieur Bayle himself, but every body else that writes of him allows) I think it will be a hard matter to persuade a disinteress'd Person, or any other but [7] a bon Francois, (which, in good English, is a Lover of his Chains) that here is any just Reason shewn why Hotoman shou'd be blam'd.

Monsieur Teissier, altho' very much prejudiced against him, was (as one may see by the Tenor of the above Quotation, and his leaving it thus uncommented on) in his Heart convinc'd of the Truth of it; but no bon Francois dares own so much. He was a little too careless when he wrote against Hotoman, mistaking one of his Books for another; viz. his Commentary ad titulum institutionum de Actionibus, for his little Book de gradibus cognationis; both extremely esteemed by all learned Men, especially the first: Of which Monsieur Bayle gives this Testimony: "La beauté du Stile, & la connoissance des antiquités Romaines eclatoient dans cet Ouvrage, & le firent fort estimer."

Thuanus, that celebrated disinteress'd Historian, gives this Character in general of his Writings. "He composed (says he) several Works very profitable towards the explaining of the Civil Law, Antiquity, and all Sorts of fine Literature; which have been collected and publish'd by James Lectius, a famous Lawyer, after they had been review'd and corrected by the Author. Barthius says, that he excelled in the Knowledge of the Civil Law, and of all genteel Learning Belles Literature Ceux la mesmes qui ont ecrits contre luy (says Neveletus) tombent d'accord quil avoit beaucoup de lecture & une profonde Erudition."

The Author of the Monitoriale adversus Italogalliam, which some take to be Hotoman himself, has this Passage relating to the Francogallia: "Quomodo potest aliquis et succcensere qui est tantum relator & narrator facti? Francogallista [8] enim tantum narrationi & relationi simplici vacat, quod si aliena dicta delerentur, charta remaneret alba."

It was objected to him, that he unawares furnish'd the Duke of Guise and the League at Paris with Arguments to make good their Attempts against their Kings. This cannot be deny'd; but at the same time it cannot be imputed to Hotoman as any Crime: Texts of Scripture themselves have been made use of for different Purposes, according to the Passion or the Interests of Parties. Arguments do not lose their native Force for being wrong apply'd: If the Three Estates of France had such a fundamental Power lodg'd in them; who can help it, if the Writers for the League made use of Hotoman's Arguments to support a wrong Cause? And this may suffice to remove this Imputation from his Memory.

He was a Man of a very handsome Person and Shape, tall and comely; his Eyes were blewish, his Nose long, and his Countenance venerable: He joined a most exemplary Piety and Probity to an eminent Degree of Knowledge and Learning. No Day pass'd over his Head, wherein he employ'd not several Hours in the Exercise of Prayer, and reading of the Scriptures. He wou'd never permit his Picture to be drawn, tho' much intreated by his Friends; however (when he was at his last Gasp, and cou'd not hinder it) they got a Painter to his Bed's-side, who took his Likeness as well as 'twas possible at such a time. Basilius Amerbachius assisted him during his last Sickness, and James Grinæus made his Funeral-Sermon. He left two Sons behind him, John and Daniel; besides a great Reputation, and Desire of him, [9] not only among his Friends and Acquaintance, but all the Men of Learning and Probity all over Europe.

Explication of the Roman Names

mention'd by Hotoman.

Ædui |

People of Chalons and Nevers, of Autun and Mascon. |

Agrippina Colonia, |

Cologn. |

Arverni, |

P. of Auvergne and Bourbonnais. |

Armorica, |

Bretagne and Normandy. |

Aquitani, |

P. of Guienne and Gascogn. |

Atrebates, |

P. of Artois. |

Attuarii, |

P. of Aire in Gascogn. |

Augustodunum, |

Autun. |

Aureliani, |

P. of Orleans. |

Aquisgranum, |

Aix la Chapelle. |

Ambiani, |

P. of Amiens. |

Alsaciones, |

P. of Alsace. |

Bigargium, |

Bigorre forté. |

Bibracte, |

Bavray, in the Diocese of Rheims. |

Bituriges, |

P. of Bourges. |

Carisiacum, |

Crecy. |

Cinnesates, |

P. on the Sea-Coast, between the Elb and the Rhine. |

Carnutes, |

P. of Chartres and Orleans. |

Ceutrones, |

P. of Liege. |

| Ceutones, | P. of Tarentaise in Savoy. |

Condrusii, |

P. of the Condros in Flanders. |

Dusiacum, |

non liquet. |

Eburones, |

P. of the Diocese of Liege, and of Namur. |

Gorduni, |

P. about Ghent and Courtray. |

Grudii, |

P. of Lovain. |

Hetrusci, |

P. of Tuscany. |

Laudunum, |

Laon. |

Lexovium, |

Lisieux. |

Lentiates, |

People about Lens. |

Levaci, |

P. of Hainault. |

Leuci, |

P. of Metz, Toul and Verdun. |

Lingones, |

P. of Langres. |

Lugdunum, |

Lyons. |

Lutetia, |

Paris. |

Massilia, |

Marseilles. |

Marsua, |

non liquet. |

Nervii, |

P. of Hainault and Cambray. |

Nitiobriges, |

P. of Agenois. |

Novemopulonia, |

Gascony. |

Noviomagum, |

Nimeguen. |

Pannonia, |

Hungary. |

Pleumosii, |

P. of Tornay and Lisle. |

Rhatia, |

Swisserland. |

Rhemi, |

P. of Rheims. |

Senones, |

P. of Sens and Auxerre. |

Sequani, |

P. of Franche Comté. |

Sequana, |

the River Seine. |

Suessiones, |

P. of Soissons. |

Trecassini, |

P. of Tricasses in Champagne. |

Treviri, |

P. of Triers, and Part of Luxemburg. |

Toxandri, |

P. of Zealand. |

Tolbiacum, |

non liquet. |

Vencti, |

P. of Vannes. |

Vesontini, |

P. of Besançon. |

Ulbanesses, |

non liquet. |

Witmarium, |

non liquet. |

[i]

The Author's Preface.↩

To the most Illustrious and Potent Prince FREDERICK, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria, &c. First Elector of the Roman Empire, His most Gracious Lord, Francis Hotoman, wishes all Health and Prosperity.

'Tis an old Saying, of which Teucer the Son of Telamon is the supposed Author, and which has been approved of these many Ages, A Man's Country is, where-ever he lives at Ease. Patria est ubicunq; est bene. For to bear even Banishment it self with an unconcern'd Temper of Mind like other Misfortunes and Inconveniences, and to despise the Injuries of an ungrateful Country, which uses one more like a Stepmother than a true Mother, seems to be the Indication of a great Soul. But I am of a quite different Opinion: For if it be a great Crime, and almost an Impiety not to live under and suffer patiently the Humours and harsh Usage of our Natural Parents; 'tis sure a much greater, not to endure those of our Country, which wise Men have unanimously preferr'd to their Parents. 'Tis indeed the Property of a wary self-interested Man, to measure his Kindness for his Country by his own particular Advantages: But such a sort of Carelesness and [ii] Indifferency seems a Part of that Barbarity which was attributed to the Cynicks and Epicureans; whence that detestable Saying proceeded, When I am dead, let the whole World be a Fire. Which is not unlike the Old Tyrannical Axiom; Let my Friends perish, so my Enemies fall along with them. Me mortuo terra misceatur incendio. Pereant amici dum una inimici intercidant. But in gentle Dispositions, there is a certain inbred Love of their Country, which they can no more divest themselves of, than of Humanity it self. Such a Love as Homer describes in Ulysses, who preferred Ithaca, tho' no better than a Bird's Nest fix'd to a craggy Rock in the Sea, to all the Delights of the Kingdom which Calypso offer'd him.

Nescio quâ natale Solum dulcedine cunctos

Ducit, & immemores non finit esse sui:

Was very truly said by the Ancient Poet; When we think of that Air we first suck'd in, that Earth we first trod on, those Relations, Neighbours and Acquaintance to whose Conversation we have been accustomed.

But a Man may sometimes say, My Country is grown mad or foolish, (as Plato said of his) sometimes that it rages and cruelly tears out its own Bowels.—We are to take care in the first Place, that we do not ascribe other Folks Faults to our innocent Country. There have been may cruel Tyrants in Rome and in other Places; these not only tormented innocent good Men, but even the best deserving Citizens, with all manner of Severities: Does it therefore follow, that the Madness of these Tyrants must be imputed to their Country? The [iii] Cruelty of the Emperor Macrinus is particularly memorable; who as Julius Capitolinus writes, was nicknamed Macellinus, because his House was stained with the Blood of Men, as a Shambles is with that of Beasts. Many such others are mention'd by Historians, who for the like Cruelty (as the same Capitolinus tells us) were stil'd, one Cyclops, another Busiris, a 3d Sciron, a 4th Tryphon, a 5th Gyges. These were firmly persuaded, that Kingdoms and Empires cou'd not be secur'd without Cruelty: Wou'd it be therefore reasonable, that good Patriots shou'd lay aside all Care and Solicitude for their Country? Certainly they ought rather to succour her, when like a miserable oppressed Mother, she implores her Childrens Help, and to seek all proper Remedies for the Mischiefs that afflict her.

But how fortunate are those Countries that have good and mild Princes! how happy are those Subjects, who, thro' the Benignity of their Rulers may quietly grow old on their Paternal Seats, in the sweet Society of their Wives and Children! For very often it happens, that the Remedies which are made use of prove worse than the Evils themselves. 'Tis now, most Illustrious Prince, about Sixteen Years since God Almighty has committed to your Rule and Government a considerable Part of Germany situate on the Rhine. During which time, 'tis scarce conceivable what a general Tranquility, what a Calm (as in a smooth Sea) has reigned in the whole Palatinate; how peaceable and quiet all things have continued: [iv] How piously and religiously they have been governed: Go on most Gracious Prince in the same Meekness of Spirit, which I to the utmost of my Power must always extol. Proceed in the same Course of gentle and peaceable Virtue; Macte Virtute; not in the Sense which Seneca tells us the Romans used this Exclamation in, to salute their Generals when they return'd all stain'd with Gore Blood from the Field of Battel, who were rather true Macellinus's: But do you proceed in that Moderation of Mind, Clemency, Piety, Justice, Affability, which have occasion'd the Tranquility of your Territories. And because the present Condition of your Germany is such as we see it, Men now-a-days run away from Countries infested with Plunderers and Oppressors, to take Sanctuary in those that are quiet and peaceable; as Mariners, who undertake a Voyage, forecast to avoid Streights, &c. and Rocky Seas, and chase to sail a calm and open Course.

There was indeed a Time, when young Gentlemen, desirous of Improvement, flock'd from all Parts to the Schools and Academies of our Francogallia, as to the publick Marts of good Literature. Now they dread them as Men do Seas infested with Pyrates, and detest their Tyrannous Barbarity. The Remembrance of this wounds me to the very Soul; when I consider my unfortunate miserable Country has been for almost twelve Years, burning in the Flames of Civil War. But much more am I griev'd, when I reflect that so many have [v] not only been idle Spectators of these dreadful Fires (as Nero was of flaming Rome) but have endeavour'd by their wicked Speeches and Libels to blow the Bellows, whilst few or none have contributed their Assistance towards the extinguishing them.

I am not ignorant how mean and inconsiderable a Man I am; nevertheless as in a general Conflagration every Man's Help is acceptable, who is able to fling on but a Bucket of Water, so I hope the Endeavours of any Person that offers at a Remedy will be well taken by every Lover of his Country. Being very intent for several Months past on the Thoughts of these great Calamities, I have perused all the old French and German Historians that treat of our Francogallia, and collected out of their Works a true State of our Commonwealth; in the Condition (wherein they agree) it flourished for above a Thousand Years. And indeed the great Wisdom of our Ancestors in the first framing of our Constitution, is almost incredible; so that I no longer doubted, that the most certain Remedy for so great Evils must be deduced from their Maxims.

For as I more attentively enquired into the Source of these Calamities, it seemed to me, that even as human Bodies decay and perish, either by some outward Violence, or some inward Corruption of Humours, or lastly, thro' Old Age: So Commonwealths are brought to their Period, sometimes by Foreign Force, sometimes by Civil Dissentions, at other Times by being worn [vi] out and neglected. Now tho' the Misfortunes that have befallen our Commonwealth are commonly attributed to our Civil Dissentions, I found, upon Enquiry, these are not so properly to be called the Cause as the Beginning of our Mischiefs. And Polybius, that grave judicious Historian, teaches us, in the first place, to distinguish the Beginning from the Cause of any Accident. Now I affirm the Cause to have been that great Blow which our Constitution received about 100 Years ago from that Lewis the XI. Prince, who ('tis manifest) first of all broke in upon the noble and solid Institutions of our Ancestors. And as our natural Bodies when put out of joint by Violence, can never be recover'd but by replacing and restoring every Member to its true Position; so neither can we reasonably hope our Commonwealth shou'd be restor'd to Health, till through Divine Assistance it shall be put into its true and natural State again.

And because your Highness has always approv'd your self a true Friend to our Country; I though it my Duty to inscribe, or, as it were, to consecrate this Abstract of our History to your Patronage. That being guarded by so powerful a Protection, it might with greater Authority and Safety come abroad in the World. Farewel, most illustrious Prince; May the great God Almighty for ever bless and prosper your most noble Family.

Your Highness's most Obedient,

12 Kal. Sep.

1574.

Francis Hotoman.

Francogallia.

[1]

CHAP. I.↩

The State of Gaul, before it was reduced into a Province by the Romans.

My Design being to give an Account of the Laws and Ordinances of our Francogallia, as far as it may tend to the Service of our Commonwealth, in its present Circumstances; I think it proper, in the first place, to set forth the State of Gaul, before it was reduced into the Form of a Province by the Romans: For what Cæsar, Polybius, Strabo, Ammianus, and other Writers have told us concerning the Origin, Antiquity and Valour of that People, the Nature and Situation of their Country, and their private Customs, is sufficiently known to all Men, tho' but indifferently learned.

We are therefore to understand, that the State of Gaul was such at that time, that neither was the whole under the Government of a [2] single Person: Nor were the particular Civitas, a Commonwealth. Commonwealths under the Dominion of the Populace, or the Nobles only; but all Gaul was so divided into Commonwealths, that the most Part were govern'd by the Advice of the Nobles; and these were called Free; the rest had Kings. But every one of them agreed in this Institute, that at a certain Time of the Year a publick Council of the whole Nation should be held; in which Council, whatever seem'd to relate to the whole Body of the Commonwealth was appointed and establish'd. Cornelius Tacitus, in his 3d Book, reckons Sixty-four Croitates; by which is meant (as Cæsar explains it) so many Regions or Districts; in each of which, not only the same Language, Manners and Laws, but also the same Magistrates were made use of. Such, in many Places of his History, he principally mentions the Cities of the Ædui, the Rhemi and Arverni to have been. And therefore Dumnorix the Æduan, when Cæsar sent to have him slain, began to resist, and to defend himself, and to implore the Assistance of his Fellow Citizens; often crying out, That he was a Freeman, and Member of a Free Commonwealth, lib. 5. cap. 3.

To the like purpose Strabo writes in his Fourth Book: Ἀριστοκρατικαὶ δ' ἦσαν αἱ πλείους τῶν πολιτειῶν, ἔνα δ' ἡγεμόνα ἡρούντο κατ' ἐνιαυτόν τὸ παλαιόν ὡς δ' αὕτως εἰς πόλεμον ἐἷς ὑπὸ τοῦ πλήθους ἀπεδείκνυτο στρατηγός. "Most of the Commonwealths (says he) were govern'd by the Advice of the Nobles: but every Year they anciently chose a Magistrate; as also the People chose a General to manage their Wars." The like Cæsar, lib. 6. Cap. 4. writes in these Words: "Those Commonwealths which are esteem'd to be under the best Administration, have made a Law, that if any [3] Man chance to hear a Rumour or Report abroad among the Bordering People, which concerned the Commonwealth, he ought to inform the Magistrates of it, and communicate it to no body else. The Magistrates conceal what they think proper, and acquaint the Multitude with the rest: For of Matters relating to the Community, it was not permitted to any Person to talk or discourse, but in Council."—Now concerning this Common Council of the whole Nation, we shall quote these few Passages out of Cæsar. "They demanded, (says he) lib. 1. cap. 12. a General Council of all Gallia to be summon'd; and that this might be done by Cæsar's Consent." Also, lib. 7. cap. 12.—"a Council of all Gallia was summon'd to meet at Bibracte; and there was a vast Concourse from all Parts to that Town."—And lib. 6. cap. 1—"Cæsar having summon'd the Council of Gaul to meet early in the Spring, as he had before determin'd: Finding that the Senenes, Carnates and Treviri came not when all the rest came, he adjourned the Council to Paris."—And, lib 7. cap. 6. speaking of Vercingetorix,—"He promis'd himself, that he shou'd be able by his Diligence to unite such Commonwealths to him as dissented from the rest of the Cities of Gaul, and to form a General Council of all Gallia; the Power of which, the whole World should not be able to withstand."

Now concerning the Kings which ruled over certain Cities in Gallia the same Author makes mention of them in very many Places; Out of which this is particularly worthy our Observation: That it was the Romans Custom [4] to caress all those Reguli whom they found proper for their turns: That is, such as were busy men, apt to embroil Affairs, and to sow Dissentions or Animosities between the several Commonwealths. These they joined with in Friendship and Society, and by most honourable publick Decrees called them their Friends and Confederates: And many of these Kings purchased, at a great Expence, this Verbal Honour from the Chief Men of Rome. Now the Gauls called such, Reges, or rather Reguli, which were chosen, not for a certain Term, (as the Magistrates of the Free Cities were) but for their Lives; tho' their Territories were never so small and inconsiderable: And these, when Customs came to be changed by Time, were afterwards called by the Names of Dukes, Earls, and Marquisses.