JOHN TOLAND,

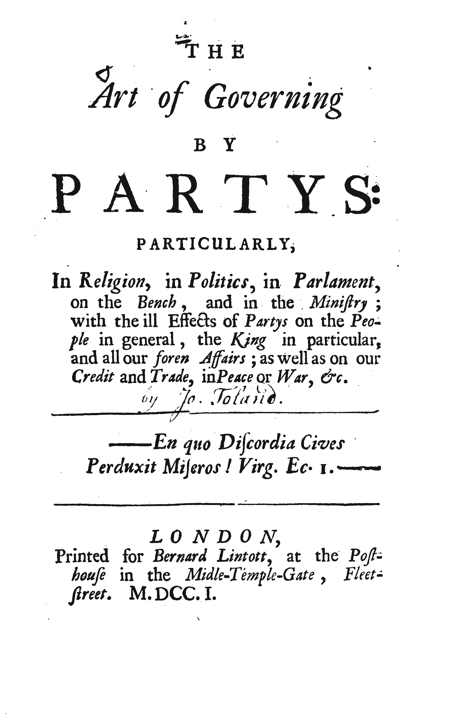

The Art of Governing by Partys: Particularly, in Religion, in Politics, in Parlament, on the Bench, and in the Ministry (1701)

|

[Created: 12 February, 2022]

[Updated: 5 July, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, The Art of Governing by Partys: Particularly, in Religion, in Politics, in Parlament, on the Bench, and in the Ministry; with the ill Effects of Partys on the People in general, the King in particular, and all our foren Affairs; as well as on our Credit and Trade, in Peace or War, &c. (London, B. Lintott, 1701).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1701-Toland_GoverningByPartys/Toland_GoverningByPartys-ebook.html

John Toland, The Art of Governing by Partys: Particularly, in Religion, in Politics, in Parlament, on the Bench, and in the Ministry; with the ill Effects of Partys on the People in general, the King in particular, and all our foren Affairs; as well as on our Credit and Trade, in Peace or War, &c. (London, B. Lintott, 1701).

En quo Discordia Cives

Perduxit Miseros ! Virg. Ec. 1.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Table of Contents

- Dedication to William, III, King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland.

- CHAP. I. The Author's Apology and Design. p. 1

- CHAP. II. The Art of Governing by Parties in Religion. p. 11

- CHAP. III. The Art of Governing by Parites in Politics. p. 31

- CHAP. IV. The Art of Governing by Parties in Parlament. p. 56

- CHAP. V. The Art of Governing by Parties on the Bench. p. 79

- CHAP. VI. The Art of Governing by Partys in the Ministry. p. 92

- CHAP. VII. The ill effects of Parties on the People in general, and the King in particular. p. 116

- CHAP. VIII. The ill Effects of Parties on all our foren Affairs. p. 141

- CHAP. IX. The only Remedy against all the Michief of Partys, is a Parlament equally Constituted. p. 164

- Conclusion. p. 176

- Faults of the Press to be thus corrected., p. 181

- Endnotes

To William, III. King of England, Scotland, France, and Ireland.↩

Statholder of Gelderland, Holland, Zealand, Utrecht, and Overyssel.

Supreme Magistrat of the two most Potent and flourishing Commmonwealths in the UNIVERSE.

May it please your Majesty,

It has bin always counted the greatest Happiness of Princes to be acquainted with the Sentiments of their Subjects, for want of which the best of 'em have often taken wrong measures, which made their Actions produce very dioffernt Effects from their good Intentions: not that the People affect to [page] hide their Thoughts (their complaints being generally represented louder, than the Grievances own'd to be hard) but Flatters are ready to persuade Kings that nothing can be amiss during their Reigns; evil or insufficient Counsillors dare not reveal the bad Consequences of their own unapprov'd Ministry; and, where a Nation is divided into Parties, that side, who is in possession of the Royal Favor, will suffer none to approach the Throne that wou'd discover the severities they exercise on [page] their Adversaries. 'Tis not to be doubted, SIR, but you have all the Information of this sort, that a Prince of such finish'd Wisdom and Experience can judg necessary; yet the writer of the following Treatise cou'd not think it unbecoming his Duty to present it to your Majesty, having there, with all possible Freedom and Impartiality, presum'd to lay before you the true state of your Subjects as to their Contrary Interests and Affections. It will easily appear (but principally, tis hop'd, to your Majesty) [page] that the chief aim of the Author was to do the most acceptable service to his Country in this critical Juncture; and yet he questions not but one sort of people will be displeas'd with him for having don Justice to your unparallel'd Zeal for Liberty (a Thing so unusual with crown'd Heads) and which they are as sorry shou'd be known, as usable to conceal: while another sett of Men will be still more offfended, because he is not an humble Prostitute after their Example, and for touching on those miscarriages whereof [page] they know themselves deserve the Blame, tho tey are ungratefully striving to charge 'em Elsewhere. But if your Majesty is pleas'd to approve of this small Essay, as intended for your Service, he'll expect no ohter Reward but to see a better Reformation practis'd than he was capable to propose; his Happiness being necessartily involv'd in the common Good, and without it no condition of Life being honorable, satisfactory, or secure.

[1]

CHAP. I.

The Author's Apology and Design. ↩

IN the prosecution of this Discourse, som people may think that I speak more freely than in Prudence I ought to do ; while others will be apt to censure me as acting out of my Sphere, and medling in matters which are none of my Concerns : but one thing I dare undertake and promise, that all unbyast Readers will think me Impartial; and I know my self to be neither aw'd by hopes or fears, nor gain’d by Favor or Bribes. Tho' all do not sit at the Helm, yet each Person on Board is equally interested about the preservation of the Ship, and may give fair warning of those Rocks [2] and Shelves which are not apprehended nor observ’d by others. Every Man is bound to assist his Country by his Advice, as well as by his Purse, or the use of his Arm; and as the Collective body of the Government is made up of many individuals, so whatever is propos’d for the Honor, Profit, or Safety of the whole, must still originally proced from som one Man, whether in the Parlament, Council, Cabinet, or after the manner I presume to do at present: and so the matter is submitted to the approbation or dislike of the greater number. This has been always an allow'd custom in England , at which none was ever displeas’d but such as were conscious of their own demerits, and had no stomach to hear their Crimes divulgd for fear of Punishment or Disgrace. As for so openly telling my mind, 'tis the honestest way of dealing; whereas obscure hints and artificial disguises are generally interpreted beyond what the Author ever intended : for what one seems afraid of saying plainly and directly, is thought by others to be naught beyond expression. Nor am I without that due regard which every one ought to have for his own [3] preservation; but I know where I am, and what I assert. I deliver nothing but the naked truth, which is the strongest, and consequently the boldest thing in the world. I live in a free Government where Men may vent their thoughts secure from the dread of Informers, represent their Greviances, yet not be counted factious, and expect redress without claiming more than their due. We have known Rules and stated Measures of our Actions. Every Man has the same right to his Property as the Magistrat to the execution of his Office: and the meanest Countryman has his action and remedy at Law against the King no less than against any of his fellow Subjects.In these and the like priviledges consists a great part of our Happiness above theirs who at no extraordinary distance from us graon under the yoke of absolute dominion. There the will of the Prince being his Law, the Judges are oblig’d to interpret it solely for his interest without any respect to the Hardships endur'd by private Men when they interfere with the pleasure of their Master. There the people are beggarly and slavish, but the Monarch is Great and Mighty, the [4] prime Nobility and Gentry being reduc'd to depend on his liberality, the Stoutest of the commons forc'd to serve in his Troops for Bread, and all degrees of Persons made the Instruments of gratifing his Vanity, Rapaciousness, or Luft. In the mean time his Clergy, Army ,and Officers of State are finely pamper'd and making a flourishing show, while the rest of his miserable Subjects languish and decay : for he aws their Consciences by his Priests, Compels their Bodies by his Soldiers,and drains their Purses by his Ministers, who all consequently share the Spoil with him as necessary Tools for his purpose,and a reward of their Iniquity. Now because no complaints dare be heard in France or Denmark , will any body say that nothing's ąmiss there? Is their Unity so much to be admir'd, when they must not use their reason to examin, and that they agree even about their Religious Tenets as Men do about Colors in the Dark. Heaven be prais'd this is not our Condition. I write within the reach of no Tyrant; but under the wings of a Valiant, Wise, and Just Prince, who is pleas’d with nothing so much as being circumscrib’d by [5] the Laws, lest for all his upright intentions he should be mistaken in his duty.Whenever therefore he is engag'd in bad Councils (as their is no absolute Perfection of Men or things) he is no sooner made sensible of his error, but he presently changes his measures, and denies nothing to the Nation which they earnestly desire and think indispensably necessary for their Prosperity and Safety. The many excellent Laws, to which (after som previous hesitation) he has agreed, are an undeniable proof of his good disposition, if we knew how to improve it; witness the Acts for Triennial Parlaments, for regulating Trials of High-Treason, concerning Mines and Ores, the late Law for Resumtions, those against Standing Armies, and several besides. It were to be wish’d, I confess, that the extreme Lenity of his Temper did not hinder him from showing greater marks of his displeasure as gainst those who have somtimes unworthily abus'd his favor, exasperated the best part of the Nation against them for breaking their trust, and temted many well meaning persons to have an ill opinion of the public [6] Administration. Seasonable and exemplary Justice on such wicked Men cou'd not fail both of clearing himself from all ill grounded Jeolousies, and of effectually discouraging others in the same stations from imitating the vicious courses of their Predecessors. Yet in excuse of this, it must be own'd that such Criminals have not only the secret of evading the censure of the Law, but that they even have frequently grown above fearing his Majesty's animadversion, combining together, and linking themselves into such powerful Factions that none of their number must be touch'd without disobliging the whole Party, which is not always safe tho’ never so just. 'Tis obsery'd that after good Government is destroy’d, its expiring virtue procures some Credit to the beginning of the succeeding Tyranny; in like manner the general depravation of Morals contracted under the Reign of one or more Tyrants, cannot be immediately reform’d by the utmost vigilance of a virtuous Prince, which makes it no strange thing if som dark clouds are observ’d to eclipse the lustre of his management. He is therefore much to be pitied, if he cannot [7] discern the Men who are not less able than willing to serve him faithfully ; and then only to be blam'd when he industriously picks out the worst, or makes an honest Man turn Knave before he is capable to do his business. Of all the Plagues which have infested this Nation since the death of Queen Elizabeth, none has spread the Contagion wider, or brought us nearer to utter ruin, than the implacable animosity of contending Parties. Tho' 'tis a thing never to be expected (nor perhaps so desirable as som may fancy) that all men shou'd agree about all things ; yet it is the most wicked master-piece of Tyranny purposely to divide the sentiments, affections, and interests of a People, that after they have mutually spent their Force against one another, they may the more easily becom a common prey to Arbitrary Power. There have bin many opposite Factions in England heretofore, partly occasion’d by dubious Titles to the Crown, partly to restrain the exorbitancy of fom Kings who invaded Liberty, and all Men continu'd uneasie till by Perswasion or Force such quarrels were adjusted. But till the accession of the Stuarts to the [8] Imperial Throne of this Realm, we never knew the Art of Governing by Parties. It was set on foot among us by the first of that Race, and was dayly improving under his Successor, till at last it fatally turn'd on himself, and depriv'd him both of his Crown and Life. But because this execrable Policy was brought to perfection under Charles the Second, I shall display som of its worst effects in his Reign, and the dismal influence it has an all our Affairs ev'n at this time. As soon as this King was restor’d to sit in the Saddle of his Ancestors, he wholly apply'd his thoughts (as he intended long before) to establish Popery and Despotic Power on the ruins of our Religion and Liberty. The revenge he ow'd his Fathers Death, together with the remembrance of his particular Sufferings, contributed not a little to alienat his Heart from all tenderness for the English : but he was fixt in his Arbitrary Designs, by the example of Foren Princes; and reconcil'd to the Roman Faith by the Authority of his Mother, the importunity of the Priests, and his own vitious inclination. A few of the [9] Nobility, Gentry, and Clergy, who accompanied him in his Exile, knew of his change ; the most quick sighted sort of People at home had violent suspitions of it; but he never thought fit quite to take off the Mask till he came to dy, and that his usual dissimulation cou'd do him no farther service. Popery and Slavery being the two great Blessings he intended to intail upon us and our Posterity, as they were the chief motives of his Actions, so they are the only Keys by which we can decipher the mysteries of his Reign. He cou'd not hope to perswade or force a compliance from a free Nation, and the Head of the Protestant Interest : what he was not able to compass therefore by open violence, he attemted with much success by secret fraud. Hinc illæ lachyrmæ. This is the true spring of all those pernicious Divisions, names of distinction, Parties, Factions, Clubs, and Cabals, which have ever since distracted, torn, and very nigh consum'd us. High and Low Churchmen, Conformists and Fanaticks, Whigs and Tories, Loyalists and Rebels, Patriots and Courtiers, with the like opprobrious nick-names, are the abominable fruits [10] of his Policy. My business is not to write the History of his Reign, but to give a succinct account of the Parties he created for our Destruction, and the malignant influence they have at this very time on our Government. Wherfore I shall consider them, as in the first place they respect our Religion, secondly our Politics, thirdly the High-Court of Parlament, fourthly Inferior Court of Judicature, and fifthly the Ministers of State. I'll make no separat head of our Morals, because they were debaucht, not only by the pattern shew'd us at Court, but also by a concurrence of many causes to be mention'd under the foregoing Heads. In the next place, I'll briefly shew what ill effects those Parties have now on the People in general, the King in particular, and all our affairs abroad. Lastly, as a prevention or perfect cure of this distemper, I'll offer som advice about the Election of Members fit to Represent and Serve the Nation in Parlament.

[11]

CHAP. II.

The Art of Governing by Parties in Religion. ↩

'TIs not more common (nor indeed more natural) for Men to vary from one another in the color of their Hair, the air of their Face, or the measure of their Stature, than it is for them to disagree in their opinions (whether relating to Religion or any other subject) by reason of their different opportunities, applications or capacities, and that things are not plac'd in the same degree of light to all sorts of People. Nobody wonders that he has not the same [12] taste or fancy with others; nay, he'll make allowance for it in eating or drinking, in chusing a Mistress, a House, a Suit of Clothes ; and yet he's apt to be amaz’d or angry that every one is not of the same Religion with himself, which makes him (like the Tyrant of old) for stretching or cutting all the World to his own size. Mens actions are never more inconsistent than in this Point; for they all naturally desire a Liberty of worshipping in that way which they believe to be most acceptable to the Deity, and they think it the highest Injustice to be deny'd this Privilege by any Government; but they are no sooner grown the reigning Party themselves, than they fall to Persecute all that Dissent from them; and so in their several turns, as every Party happens to get uppermost, they tolerat no other Religion, because they think their own to be the best. I am not examining now the Equity or Injustice of this Procedure, but barely relating matters of Fact. The establish'd Church of England laid very great Hardships on the Nonconformists [13] before the last Civil Wars; and the Nonconformists paid the Churchmen home in their own Coin with Intereft, when they got the Power into their hands. The Church being restor'd again with the Monarchy , Charles the Second was too well acquainted with the Nature of Mankind, to let an opportunity slip which made so much for the Game he design'd to play; and therefore pretending a wonderful Zeal for the Hierarchy, he animated the Bishops (who were prone enough to Revenge, on the account of their late Sufferings) to oppress and extirpat the Presbyterians, Independents, Anabaptists, Quakers and Protestant Dissenters of all sorts. In the mean time, the Complyance of these being fear'd about all things, it was render'd wholly impossible by the hard Terms which were offerd them. He perfectly knew their main Scruples against Conformity, and having a Parlament of the same temper with his Clergy, he got such Oaths, Tests, and Declarations fram’d, as he was sure they could never swallow, which would necessitat them (as in [14] effect it did ) to form themselves in to a separat Party, and, notwithstanding their privat Dissentions, to unite together for their common Liberty against the Court and the Church. All this while he made the Clergy believe that it was his Affection to them which producd those Severities against their Enemies, frightning them from time to time with his Apprehensions lest Presbytery should ever prevail again: nor was he less industrious with the Royalists, to keep the Commomwealtb-men under. And, in order to secure them both, he pretended that they could not invest him with too great a Power , declaring, that no body must expect to partake of his Favor who was not a good Churchman as well as a true Royalist ; and that all others were Rebels in their Hearts, only waiting for a fit occasion to destroy both Church and State. The Pulpits immediatly founded with nothing else but Passive Obedience and Non-resistance to all the King's Commands, of what nature soever under pain of Eternal Damnation ; that if our Property, Religion [15] or Lives should be attack'd by him; we must have recourse to no defence but Prayers and Tears; and that Monarchy as well as Episcopacy was of Divine Right, with the like extravagant Doctrins. In short, the poor Dissenters were us'd like Dogs, prohibited to meet together for Divine Worship, expos'd to the Scorn and Rage of the Mob, crowded and starv’d in Jails, som forc'd and som flying into foren Countries, to the inexpressible damage of Trade, dispeopling the Kingdom, and diminishing the Public Revenues. But above all, the Protestant Interest was daily weaken’d by such as most pretended (and most of them, no doubt, design’d) to support it; for the mistaken Zeal of som, and the restless Ambition of others among the dignified Clergy, deluded the Herd of their Admirers. At length the continual Encroachments made on the civil Constitution, under pretence of suppressing Phanaticks, and the barefac'd Countenance given at the same time to avow'd Papists, (being receiv’d into the chiefest Trust and Confidence) [16] open'd all Mens Eyes, and discover'd the black Designs of the Court. The Laity grew weary of being the Drudges of the Clergy to ruin innocent People, very devout in their way, true to the Liberties of their Country, and the irreconcilable Enemies of Popery. It is certainly , says the Duke of Buckingham in the House of Lords, a very uneasie kind of Life to any man, that has either Christian Charity, Good Nature, or Humanity, to see his Fellow-subjects daily abus’d, devested of their Liberties and Birthrights, and miserably thrown out of their Posessions and Freeholds, only because they cannot agree with fom others in Opinions and Niceties of Religion,to which their Consciences will not give them leave to assent, and which, even by the consent of those who would impose them are no way necessary to Salvation . When the generality of the People began to utter their Complaints in such Language as this, and that the best Men on all sides were for mutually tolerating one another, or coming into a stricter Union, then the subtil King, finding it make for his purpose, would be the first to grant Dissenters [17] Liberty, and even to dispense with the Penal Laws in their favor. By this means he hop'd to kill two Birds with one Stone: for by the same dispensing Prerogative he could recall this Toleration at his pleasure; but (what was the main thing aim'd at) he could as well repeal all other Laws, if he were allow'd to suspend any one by his own Authority. He doubted not but the Dissenters would accept of Ease on any Terms, tho' he found himself mistaken: for such of them as happn’d to be Members of Parlament, oppos'd this Suspending Power the fiercest of any, and the Monarch plainly betray'd his own Plot, since he could never be induc'd to confirm their Liberty by Laws which the Parliament seem'd willing to enact; as there was one Bill expresly pass’d both Houses to this purpose, but stoln or mislaid by his order, when he ought to have given it his Assent. On the contrary, when he heard that there was a Project of Comprehension on foot, he ask'd the Archbishop, whether he was for it, who replying, He had heard of such a thing; No, said the [18] King, I'll keep the Church of England pure and unmixt . But I cannot so well excuse the conduct of the Dissenters in the Reign of his Successor. No Popish Prince in the World did ever suffer Heretics (as they call them) to live peaceably in his Dominions, but when he wanted Power to deal with them: now King James not being able to Dragoon his Protestant Subjects, nor to bring them by shoals to Smithfield, was resolv’d, in imitation of his pious Brother, to dash them in pieces against one another. All the moderat part of the Church of England had endeavor'd to exclude him from the Crown, or to frustrat his tyrannical Designs; and at last the mistaken Zealots themselves, with the high-flyers for Court-Favor and Preferment, whose Bigottry and Violence brought the Nation within an Ace of its Ruin; when they saw all Civil and Military Posts a filling with Papists, and that after they had perform'd his Drudgery, they might turn or burn, as they lik’d, for they were not the Priests he minded to exalt : all these, I say, were now for [19] Resistance, as much as ever they were for Obedience before ; nothing was heard but The Temple of the Lord, the Temple of the Lord ; and their Cry reach'd even into Holland. The grateful Prince desir'd no better, being glad at heart to be rid in such a manner of those whose infinit Obligations he never intended to repay; and so he very unexpectedly turns all his Favor towards the Dissenters, whom he mortally hated during his whole Life, and was the principal Author of their Miseries. Tho' this preposterous Kindness cozen'd very few of them, yet who now but they ? None more admitted into his Privacy, their former Persecutions solely laid to the charge of the Bishops, who were grown the most rebellious and worst of Men, while just on the sudden a Phanatick was the most loyal and peaceable Creature on Earth, next to a Papist. To crown the Work, he assumes the Power of dispensing with the Penal Laws of every kind, and in spight of all Tests, imploys both Papists and Dissenters in Offices of Trust and Honor. All wise Men saw, that [20] the advancement of Popery was the only thing at bottom, while one Party of Protestants were cajold till they had help'd to ruin the other, and might then enjoy the gracious Favor of being last destroy'd themselves. I am far from blaming the Dissenters for meeting in public to perform their Worship ; whatever was design'd by the King, they were bound to do their Duty whenever they had opportunity: but I absolutely condemn such as made Addresses to him on this account, or accepted Offices in Corporations, which was in plain truth to thank him for governing without Law, and to act by virtue of his Arbitrary Power. 'Tis true, the bulk of Dissenters abhorr'd these Proceedings of their Brethren, their Enemies themselves being Judges ; and tho' Pen, Lob, Allop, and a few like them, were familiar in his Closet, they were disown'd therein by the best of their several Communions. For my part, setting the Virtues and Failings of both sides in a just parallel, I am of opinion, that neither of them ought to reproach the other, [21] nor unmeasurably to overvalue themselves; I mean, with respect to one another : for as they have each of them been Persecutors and Persecuted, and that the Church defended the Protestant Religion from the Pulpit and the Press against K. James , as the Dissenters did our Civil Liberty against King Charles ; To both of them have hitherto unanimoully maintain'd our Religion by their Wealth, Swords and Pens, under the auspicious Conduct of King William , the unfeign'd Protector of both. The Body of the Church was always right, and the Dissenters have now got that Liberty establish'd by a Law, which every honest man wish'd them from his Heart before. The People of both sides are dispos'd to be quiet, as long as their Priests will let them: They think not a jot the worse of one another, for not walking the same way to Church on Sunday , because they joyn’d company the Saturday before to Market: They judge of one anothers Honesty by their Dealings, and not from their Notions : Trade is vigorously carry'd on without distinction: [22] other Protestants dare venture now to settle among us, and not, as formerly, shun our inhospitable Shore: no man is forc'd to inform against his Neighbor, or to disturb his own Relations : both sides are under mutual (and I hope indissoluble) ties of Marriages, Interests, and Friendship; and, in one word, we all enjoy the incomparable Blessings of Unity, Peace, and Liberty. I once met with a Person who profess’d himself amaz’d to find so many Englishmen, in the late Reigns, endeavoring to subvert our Constitution ; but, I think, there's greater reason to wonder, that after what has pass’d, there could be found one man, who entertain’d a design of repealing the Toleration : and yet not a few such there be, Men tainted with the old Leven, who maintain a profound Respect for their old Master, and are secret Admirers of the old Whore of Babylon . I'll not insist on their ill-natur'd Grumblings ever since this Revolution, nor the little Arts they have cop’yd from the Royal Brothers (and which they have been striving to put in practice these last two or three [23] years) I mean, their attacking the Quakers first, as the weakest Party, thinking they'l be abandon’d by all the rest, who sooner or later must expect to fall under the same Condemnation ; but let no man help to fire his Neighbor's House, that loves the safety of his own. At this very time there's more than ordinary Talk of this Affair, and som Cardidats for places in Parlament being exalted with Chimerial Hopes, or thinking to gratify a certain warm Set of Gentlemen, make large Promises of promoting it; but, I dare say, there's no County or Burrough in England will chuse them, if once they discover their Intentions. However, it won't be amiss on this occation to put our Church in mind of her Pious Resolutions, and the sincere Vows she made in the days of her Calamity. One of her stoutest Champions against Rome, in the last Reign, delivers the Sense of his Party in these words: [1] The Church of England, says be, is so sensible of the Iniquity as well as Folly of that method (of Persecution) that there [24] is no ground to suspect She will ever be guilty of it for the future. They whom no Arguments could heretofore convert, the Court (whose Tools they were in that mischievous and unchristian Work, and by whom they were instigated to all the Severities which they are now blam'd for) by objecting it to them as their Reproach and Disgrace, and by seeking to improve the Resentments of those who had suffer'd by Penal Laws, to becom a united Party with the Papists for their Subversion) has brought them at once to be asham'd of what they did, and to Resolutions of promoting all Christian Liberty for the time to com. And should there be any peevish and ill-natur'd Ecclefiaftics, who,upon a turn of Affairs,would be ready to assume their former Principles and pursue their wonted Course; we may be secure against all fear of their being successful in it, not only by finding the majority as well as the more learned both of the dignify'd and inferior Clergy unchangeably fixt and determin’d against it, but by having the whole Nobility and Gentry, and those noble Princes, whose Right it will be next to ascend the Throne, fully possest with all the Generous and Christian Purposes we can defire, of making [25] provi sion for Liberty of Conscience by a Lav . This Passage is not only pertinent to my present design, but a perfect Abstract and Confirmation of this whole Account: Nor do I question in the least, but that, as this Judicious Author obierves, the soundest part of the Clergy, and all the Gentlemen of England , will unanimously make good what they have so happily concurr’d with the King, and our late Queen, to establish. [2] Another acknowledges, That the Nation has scarce forgiven som of the Church of England the Persecution into which they have suffer'd themselves to be cozen'd: tho' now that they see Popery bare-fac'd, the stand they have made, and the vigorous opposition that they have given to it, is that which makes all Men willing to forget what is past, and raises again the Glory of a Church that was not a little stain'd by the Indiscretion and Weakness of those who were too apt to believe and hope, and so suffer'd themselves to be made a Property to those who would make them a Sacrifice. A third Author, to name no more, highly extols the Dissenters [26] for their unshaken Behavior under Charles the Second: [3] That Honest People, says he, tho' hated and malign’d by their Brethren, rather than be found aiding the King in his Usurpations over the Kingdom, have chosen to undergo the utmost Calamities they could be made subject unto, either thro the execution of those Laws which had bin made against them, or thro our Princes and their Ministers wrecking their Malice upon them in arbitrary and illegal methods. Now as the Churchmen, who forget this Language, and are for breaking the present Toleration, deserve to be censur’d, so the Dissenters have not been wholly blameless in this Reign; they have shewn but too much Countenance to the late Attemts against the Quakers , which will make others have the less Compassion for themselves, if ever they should fall again under the Lash of their Enemies, which is a thing not impossible. I know they justifie their promoting Penal Laws against the Socinians, as if it had not bin for any difference in Religion, but on the account of Blasphemy : but let them [27] read Fox's Martyrology, and they'll find Queen Mary 's Judges made use of that Distinction before them; for they pretended not to burn the Protestants for any speculative Notions, but for refusing actual Worship to Jesus Christ in the Sacrament, which they interpreted a denying of Honor to God, and so to be consequently Blasphemy. They would likewise do well not to ingage one another in public Disputations, nor to accept of Challenges to this purpose from their Adversaries. 'Twas never known that such Meetings produc'd any good effects, where the Antagonists (like so many Gladiators) eagerly contend for Victory, and mind nothing less than the search of Truth. Each Party misrepresents the other in the accounts they give of their Proceedings: besides that, this is the ready way to occasion Tumults, to the endangering the public Peace. 'Tis not Liberty but Licentiousness, and was never intended by the Toleration. If they be not likewise fatally blind, they may perceive the Endeavors which are us'd to draw them into a Paper War, which they ought by all means to avoid. But [28] their most general Failing is, being a little too much Courtiers of late. I know this to be an honest Mistake, partly occasion'd by their fear of the Common Enemy, and partly out of gratitude to the King, for being so instrumental in procuring their Liberty. A great deal is certainly to be allow'd in both these cases, but yet such Pretences may be carried too far ; witness their being last Year almost all for a Standing Army, and for som other invidious points. I heard an eminent Person say, not long since, That the Dissenters were the Tories of this Reign; and, that they made as great Bugbears of France and Popery on all occasions now, as others made in former days of the Monarchy and Church. I have bin the longer on this Head of governing by Parties in Religion , because it enters more or less into all our other Divisions, and has bin not only the chiefest, but also the most successful Machine of the Conspirators against our Government, well knowing with what fury Men oppose one another, when they imagin they are fighting for God, and hazarding the Salvation of their Souls. [29] But we must in Justice observe, that King William is so far from setting his Subjects together by the Ears about Religion, or making it only a politic Fetch to serve his privat Ends, that on his Accession to the Throne, he (together with the late Queen) summond a Convocation of the Clergy, either wholly to compose our Differences, or to make the terms of Communion with our Church so easie, that very few Protestants, at home or abroad, would scruple conforming with it. The chief Heads recommended in their Commission were, Convenient Alterations in the Liturgy, Ceremonies, and Canons; the correcting of Abuses in Ecclesiastical by Courts ; the Examination of Persons who were to be admitted into Orders, as well as the removing of scandalous Ministers; and Reformation of Manners in the Clergy and People. If you know who obstructed such pious Designs, you likewise know who repine and murmur at the present Toleration. But we despair not of yet seeing a better Temper towards the accomna plishing, so desirable a Union, which [30] can never be effected but in the way of Peace and mutual Condescensions : for, as Sir William Temple rightly observes, Whosoever designs the change of Religion in a Contry or Government, by any other means than that of a general Conversion of the People, or the greatest part of them, designs all the Mischiefs to a Nation that use to usher in or attend the two greatest Distempers of a State, Civil War or Tyranny ; which are Violence, Oppression, Cruelly, Rapine, Intemperance, Injustice; in short, the miserable Effusion of Human Blood, and the Confusion of all Laws, Orders, and Virtues among Men. Such Consequences as these, I doubt, are somthing more than the disputed Opinions of any Man, or any particular Assembly of Men, can be worth; since the great and general End of all Religion, next to Mens Happiness hereafter, is their Happiness here . To conclude this Point; both Parties may safely take the friendly Advice of one not servilely addicted to either, when they consider that Themistius, a Heathen Philosopher, being heartily concern'd for the common Good, offer'd such convincing Reasons against Persecution [31] to Valens the Arian Emperor, that he stop'd his Severities against the Orthodox Christians.

CHAP. III.

The Art of Governing by Parites in Politics.↩

AS King Charles deluded the Clergy into his measures by the fear of Presbytery , his next Trick was to divide the Laity in their Politics, and to possess the Royalists with apprehensions of a Commonwealth. All the World knows that England is under a free Government, whose Supreme Legislative Power is lodgd in the King, Lords, and Commons, each of which have their peculiar Privileges and Prerogatives; no Law can pass without their common Authority or Consent; and they are a mutual check and balance on one another's Oversights or Encroachments. This [32] Government is calculated for the Interest of all the Parties concern’d, which are all the Inhabitants of England ; wherfore it depends on their Good will, and is supported by their Wealth and Power. Bur in Absolute Monarchy all things are only subservient to the Pleasure or Grandeur of the Prince, who therfore by force of Arms maintains his Dominion over the People, on whom he looks but as his Herd and Inheritance, to be us'd and dispos'd as he thinks convenient. In opposition to such arbitrary Governments, those have bin call'd Commonwealths, where the common good of all was indifferently defign'd and pursu’d. But tho' they agree in their main end , yet they often differ about the means, in the names of their Magistracies, and som other Circumstances. Thus the two Kings of Sparta had no more Authority than a Duke of Venice ; and the Statholder of Holland has more real Power tho' less State and Dignity than either of them. A Commonwealth, when the Administration lies in the People, is call'd a Democracy, when [33] 'tis solely or for the most part in the Nobility, 'tis then an Aristocracy ; but when 'tis shar'd between the Commons, the Lords, and the supreme Magistrate (term him King, Duke, Emperor, or what you please) 'tis then a mixt form, and is by Polybius and many Judicious Politicians among the Ancients esteem'd the most equal, lasting, and perfect of all others. In this sense England is undeniably a Commonwealth, tho' it be ordinarily stild a Monarchy because the chief Magistrat is call'd a King. Such as are afraid therfore that England should becom a Commonwealth, may be suspected not to understand their own Language, and those who talk of making it one, may dream of turning it into an Aristocracy or Democracy, but can never make it more a Commonwealth than it is already. This is our admirable Constitution. But it will be thought strange, that any Persons fhould be found endeavoring to strip themselves of their Liberty, and to leave all their Posterity enslav'd ; yet experience will not let us doubt that [34] there is any thing so absur'd into which som may not be cheated or corrupted. The several Factions who usurp'd the Government, and maintain’d themselves by military Force before the Restauration, assum'd the Title of a Commonwealth, tho' they were the farthest imaginable from the thing. The People, who smarted under their Tyranny, abhorr’d the very name ever after ; tho' they have given sufficient demonstration since that time, that there are not more passionat Lovers of Liberty on Earth. King Charles, who wanted no Cunning, took the advantage of their mistake, and bubl'd us almost out of our Constitution before we perceiv'd it under hand. Every body was afraid of relapsing into the former Confusions; and he dextrously insinuated by his Instruments, that nothing but the increase of his Prerogative could possibly prevent it. All the Dissenters from the Eltablish'd Church were made to pass for Commonwealths Men, nor cou'd a Man escape that Imputation who grudg’d the King any power, tho' never so [35] dangerous, insomuch that all Mouths were stop'd, and the friends of their Country cou'd only privatly lament its approaching Ruin. At last the patience of good Men being quite worn out, they begun to complain loudly of their grievances, and the Creatures of Prerogative as loudly oppos’d them, which made them mortally hate one another of course, while the King laugh’d in his sleeves at the sport, and took special care to keep their animosities alive. The charge of Rebellion was urg'd as much by one side, as deni’d by the other; and both made the highest pretences to Loyalty, tho' each of them wou'd wholly Ingross that virtue to themselves. They branded one another with opprobrious Names. In Parlament they were call'd Patriors and Loyalists, or the Court and Country Parties: but in all other Places they were distinguish'd into Whigs and Tories, being the names of Highwaymen in Scotland and Ireland ; the Courtiers intending thereby to make the Patriots pass for Presbyterians, and the Patriots reproaching the [37] Courtiers with Popery. Considering all things, 'tis a much greater wonder that the Whigs were not quite destroy'd, than that they had a great while the worst on't, being excluded from all Favor at Court, and doom'd to Hell by the Church, as if Heaven and Earth had combin'd against them. Under color of keeping them under Hatches, a great part of the Protestants were disarm’d, turn'd our of their posts in Corporations, debarr'd from all Offices of Profit or Honor, standing Forces kept on foot, and, not to be too particular, there was nothing so Arbitrary or Illegal which was not encourag'd by the Tories, against the Whigs, tho they might be sure to suffer by it themselves (as plainly they did) at last. The Papists all the while were not only conniv'd at, secretly carest, and allow'd to be very Loyal Subjects, but also publicly tolerated and admitted against Law into Civil and Military Imployments. But no Engin serv'd half so well as the deluded or ambitious Churchmen to inflame these differences, and to render [36] that Party odious which they took for Enemies to themselves and the King : for the Clergy can make a sudden and universal insinuation of whatever they please, by reason of their subordinate degrees, and their being posted more commodiously than any Army, one at least in every Parish all over the Kingdom. They publish'd therefore and infus'd every where the orders of the Court, they were very busie, and had no small influence in Elections for Members of Parlament. They Preach'd not only Passive-Obedience and Non-Resistance, but recommended and approv'd all the King's illegal proceedings in taking away the Charters or Freedoms of Towns ; making of unqualifi'd Sheriffs, and packing of Juries to deprive Men of their lives under forms of Law; imposing Arbitrary and Exorbitant Fines on such Persons as did but complain or modestly assert our Rights; the frequent Proroguing and Dissolving o: Parlaments, without giving them time or opportunity to consider the good of the Nation: and, as if all this and a great [38] deal besides were not enough, they ridicul'd the horrid Plots of the Papists against their own Religion, and labor'd to fasten them on their Protestant Brethren. Such as these were the Men who then appropriated to themselves the name of the Church of England, but were really the scandal and betrayers of it, mercenary Drudges of the Court, and the bubl'd Tools of Popery. But to their eternal Honor, most of those who were eminent for their Learning, Birth, or good Sense, continu'd stedfast to the true Interest of the Protestant Religion, and our excellent Government. Tho the Conspirators and Desertors made a mighty noise, yet their number was contemptible in Comparison of the honest Churchmen, who were not to be frighted or cosen'd out of their Duty. Indeed moderat Men were disincourag’d at that time; but they bore it patiently, as became their Character. They were all both Clergy and Laymen made to pass for Whigs, and the Whigs to be all Presbyterians; yet much the greatest and ablest part of those call'd Whigs then, [39] and at this present time, are sincere Members of the Church of England : but som will admit none to be a true Churchman, who is for allowing any Liberty of Conscience to others; and if they mean the Church of Rome while they pretend the Church of England , they are certainly in the right. In Ireland, where they had no measures to observe in King James's time, the Papists exclaim'd against High-Churchmen, Low-Churchmen, and all Protestants promiscuously, as a pack of disloyal Whigs; which, one would think, shou'd perswade them now to a stricter union, or, at least, to forbear all contumelious distinctions. We may perceive what nunbers were gain'd, and what advances were made to arbitrary Power in the late Reigns, by the Addresses and Abhorrences then presented from all parts of England , fom thanking the King for dissolving a Parlament, others that he condescended to let any meet, and many incouraging him to summon none at all. There wanted not such as maintain'd the natural and divine right of Arbitrary power it self [40] as well as of Kingship, witness the Publication of Filmer's Patriarcha ; and those thought themselves very modest who (with Doctor Brady ) made us legal Slaves, affirming that we lost all Title to Liberty or Property by the Conquest of William the Norman, and that any thing possest by Englishmen since was from the favor of our Kings, which they might recall at their pleasure. In such perillous times 'tis no wonder if several noble and worthy Patriots lost their lives by privat Assassinations, captious quirks of Law, false and perjur'd Evidence; nor was any method thought too dishonest or barbarous to reach those who wou'd otherwise be rubs in the way of their designs. Notwithstanding all these Discouragements, that Party who espous’d the defence of Liberty and Property maintain’d themselves against the craft and power of Lewd and Arbitrary Kings, against a flattering Clergy, a prostitute Ministry, a corrupt set of Judges, a mercenary Army, and Justices purposely chosen to oppress them. There are great complaints [41] now of the Immortality of the Nation, and I wish there were not such just reasons for it: but with all our failings it can scarce be paralel'd in History, that any People under the like Circumstances preserv'd their Liberty. This may well be allow'd for a miracle, tho I must reckon it a greater that any remains of these Animosities shou'd disturb us under the present King, who is no way ingag’d in the treacherous designs of his Predecessors; but on the contrary came generously to rescue us from Popery and Slavery, and to secure us for ever hereafter from those worst of Plagues. Yet there's but too much of these ill humors stirring among us still. Divisions ought carefully to be avoided in all good Governments, and a King can never lessen himself more than by heading of a Party; for therby he becoms only the King of a Faction, and ceases to be the common Father of his people. If he's visibly partial to one Party, and confers on them only all Places of Honor and Profit ; he naturally makes the other Party hate him, who, finding themselves [42] unjustly excluded from Confidence and Preferment, will be incessantly laboring to destroy him as their Enemy and Oppressor. The Matter is still worse if instead of Governing his whole Kingdom, he's actually Govern’d himself by a Party; for they care not in what dishonorable, difficult, or desperat attemts they involve him, to gratifie their revenge on the other side, whom they fail not to represent as Enemies to his Person, or Dangerous to his Government, and they are sure to be treated accordingly. But the worst of all is, when he not only chuses to Govern by a Party, but is given to change sides as he finds it make for his turn, or as either of them happens to outbid the other in executing his projects, or complying with his desires. Then all the Administration grows unsteddy, Councils uncertain, no Union at home, less Credit abroad, and a general slackness in Execution; no body knowing what Party to please, or how to act with security, since what is allow'd by those in present power, may for no other reason be [43] disaprov'd by the others when it coms to their turn to be the Favorits. And such Revolutions are quickly made : for as soon as one Party looles their Credit with the Nation, or refuses to grant any of the Princes demands tho never so unseasonable, they are turn’d off without farther Ceremony, and their mortal Foes advanc'd into the Sadle. If a Man were so indifferent or hard-hearted as to sport with our Calamitys, it were no unpleasant entertainment to consider what miserable handles are taken somtimes when the disgrace of a Party is resolv’d. The Knavery, for instance, or Miscarriage of som few is heavily charg'd on all those of the same denomination, and nothing less can do than wholly to change hands for the opposit Faction ; just as if there were no wiser or honester Men among the Whigs, than those who were lately turn’d out. But as his present Majesty dos not govern by such Arts, so there are not produc'd for an Example ; nor is there any fear of his imploying Tories on this account. As no [44] mortal, tho' incomparable for virtue, or in never so exalted a station, is secure from the censures of Jealous, Weak, and Malitious Persons; so we must not dissemble that even King William was calumniated by many to affect this method of governing by Parties that is in Plain English of governing by Tricks. The unhappy accidents that gave occasion to this surmise are very accountable : and I question not so to vindicat his Majesty from such an unjust Imputation, that he must stand clear of it in the minds of all his loving Subjects. Pursuant to his Heroic and God-like design, he resolvd on his first coming here to abolish our infamous distinctions both in Church and State, and intended to receive the good Men of all Parties into equal Favor, Protection, and Trust : not that he design’d to Imploy any who continu'd still a Tory ; that is, who retain'd his old notions of Passive Obedience, unlimited Prerogative, the divine right of Monarchy, or who was averse to Liberty of Conscience. But thinking that, according to their own [45] declar'd Resolutions, they had quitted such wicked Principles as had lately endanger'd their Ruin, he elevated several of them to the most eminent Posts in the Kingdom. Nor was he too hasty in trusting them, considering that in the latter end of King James's Reign they openly acknowledg'd their shame for being made such tools to his Brother and him, pretended a world of sorrow for contributing so much to our past and present misfortunes, and exprest hearty resolutions of future amendment. And, in effect, all differences seem'd to be forgot when the Prince of Orange landed. But alas ! the Tories quickly return’d to their Vomit, they fiercely oppos’d the making him King, would have him at most but a Regent accountable to his Father-in-Law, whom they positively refus’d to abjure, us'd their utmost endeavors to restore the Latter, affirming him still to be the rightful King, and allow'd the former to be only a King de facto. Notwithstanding this ungenerous Treatment , King Willam, a I said before, admitted several of them into [46] his Councils and Ministry, without gaining the Party to his Interest; they appear'd displeas’d with his good Fortune, rejoic'd whenever they heard of his ill Success, and som of them dayly betray'd him by means of those very trusts he had plac'd in their hands. The frequent discovery of their Plots, Correspondence, and Treacheries, with a universal series of design’d mismanagements in every Part of the Goverment, opend the Eys of all who were unalterable friends to their Country; and they made the K. fo fensible of his own and the Nations most dangerous Condition, that he betook himself to the only proper remedy of saving both, which was by placing the Administration in the Hands of Persons that had oppos’d the late Usurpations, help'd to advance himself to the Throne , and were all their Lives the profess’d Enemies of Popery and France. Yet (according to that merciful disposition which is natural to him) he laid aside the Torys, som so Privatly, som so gently, and others with so much seeming Reluctancy, that many of the warm [47] Whigs exceeded the Bounds of Decency on that account; they Swore that all Kings were alike, that the Fault lay in the Office and not in the Persons, that every one of them lov'd Arbitrary Power and Consequently Men of Arbitrary Principles, that they had only chang’d the Huntsman but that the Hounds were to be still the same : and that they hop'd for little benefit from having the Whigs prefer’d, believing that either they must do such things as were only fit for Torys, or that they must be soon turn'd out as a parcel of stubborn, opinionative, and uncourtly Fellows, who were strangers to the Art of pleasing Kings, Cheating the People, and inriching themselves. However they were quickly cur’d of their Mistake, the King fell in heartily with the Public Interest, his new Ministers serv'd him faithfully for a considerable Time, and all our Affairs took a better Face both at Home and Abroad, by Land and Sea. But see the Instability of human Councils , som of those surly Whigs grew by degrees the most pliant Gentlemen [48] imaginable, they cou'd think no revenue too great for the King nor would suffer his Prerogative to be lessen'd, they were on frivolous pretences for keeping up a Standing Army to our further Peril and Charge, they filled all Places in their disposal with their own Creatures, combin'd together for their common Impunity, whoever found fault with their Conduct they represented him as an Enemy to the Goverment, and even oppos’d the best of Laws, lest the Torys, as they said, shou'd partake of the Benefit. Surely these Gentlemen, if it were in their Power, wou'd not suffer the Sun to shine on any but themselves and their Faction. But as this Language, this Partiality, this Conduct, were directly contrary to the Principles and Practices of the Whigs (and the Torys themselves will do Justice to the old Whigs) so these Apostats were abandon’d by their former Friends, and left to the support of their own Interest,which appear'd to be so very little with any Party that the King did wisely cashier them. Indeed som People who were well enough pleas'd [49] with this piece of Justice, are yet so weak as to fear lest he shou'd now establish a Tory Ministry ; but this is in good earnest to think him weaker than themselves, since he has already experienc'd both the Inconsistency of a Tory Administration with the Genius of the Kingdom, and their irreconcilable hatred of his own Person. 'Tis manifeft by all his steps that he loves not to govern by Partys, but rather when his Ministers form themselves into Partys, he'l have nothing to do with them any longer: But what need they be afraid ; for supposing the worst (tho I am confident the supposition is absurd ) what can he gain by taking in the Torys, whose Interest can hold no balance with that of the Liberty and Property Men? He may soon be reduc'd to the same straights and uneasiness, as in the first four years of his Reign, and be oblig'd to hear the same ungrateful clamors again: or suppose yet farther, that the Torys (from a sense of the violence of their Nature, and the smalness of their number) shou'd attemt to govern by [50] force, as they did in the late Reigns, then let them remember that they have to do with. Whigs, Men that will neither be frighted nor flatter'd out of their Liberties ; Men that will adhere to their principles in spight of Discountenance, Prisons, Exile, or Proscriptions; and Men, in short, that may be cheated twice, but will make sure work the third time. They have som Fools and Knaves among them, as all great Bodies must needs have, when there was a Judas among twelve Apostles : but nine parts in ten of the Kingdom are certainly in the scale of Liberty. Now to leave suppositions, ’tis notoriously known that they were the Whigs themselves who bore hardest on som of the late Ministry, that they were Whigs who wrote all the Books against standing Armys, or for making the Fleet and Militia useful ; and that no Tory cou'd openly oppose the Court but on a Whíggilh bottom, leaving the honor of their secret Conspiracies to their own Principles. But as I have made it plain that King William has never yet degraded himself [51] to becom the Head of any Party : so I dare engage he'll never do it the rest of his time, which I pray God may be long and prosperous. Next to our Preservation, his chiefest Care will be to bring us all into the same Interest, which is the only thing that can heal our Divisions. The mischiefs proceeding from the difference of Partys are too much felt not to be known, and I shall have occasion in this Treatise to mention the worst of them: but there's one particularly which is not so easily perceiv’d, yet has as pernicious effects as any of the rest ; and it is that a world of People change their Principles or act in contradiction to them, while at the same time they go under their old denomination, whereby the simplest, and therefore the greatest part of their friends, are frequently cheated. For such a person having bin all his Life reputed a Whig (for example) and still calling himself to, they continue their good opinion of him tho he is the most corrupt Man a live, and is purchafing Wealth or Honor at the [52] price of those Liberties which they intrusted him to preserve. Nay tho somtimes with their own eyes they see him do what they wou'd approve in no other, and cannot defend in him, yet they are apt to imagin that he steps out of the common road with som honest design; and so he is supported by the credit of that Party which he is discrediting or destroying all the while. I need not bring examples of what we behold every day. On the contrary, if one who was a Tory in the late Reigns asserts our common Rights with all the Reason and Vigor that may be ; yet they'll never believe him sincere, and will often oppose their own Interest because promoted by one, who they cannot be perswaded, intends them any good. Thus they run headlong into two extremes, as if no Man once in the right cou'd ever be afterwards in the Wrong, or no Man once in the Wrong cou'd ever com to be again in the Right. The former of these Opinions is as foolish as the latter is uncharitable. But there's one evident Inference to be drawn from [54] those people's mistakes, that we may be often deceivid in Men, but never in Principles. Men may go backwards and forwards, but Principles are eternally the same; wherfore the Actions of a Man, and not his Profession, are the best demonstration of his Principles. The warmest opposers of Prerogative in the three last Parlaments of Charles the II. were either Cavaliers, or the Children of such; and the Liberties of England are not a little beholding in this Reign to Torys, I mean to persons so esteem'd, or who perhaps were in reality such before they had better information. But shou'd it be demanded if I wou'd have no distinction made between Whigs and Torys, if I wou'd have them both indifferently taken into the Ministry, or chosen into Parfament ? I answer, in the first place, that those, who, out of privat designs or particular Quarrels, combine together, and enroll themselves into such Factions, ought to be excluded our of all places on all hands. But I answer secondly, that understanding Whigs and Torys as I have stated [54] those Names in the former part of this Chapter, there can be no balancing in prefering a Whig to a Tory ; that is, a free Goverment to Arbitrary Power, the Protestant Religion to Popery, England to France, and, if I may add one thing more, King William to King James. But then it must be remember'd that no great heed is to be given to names or times ; for the best way of discovering the true Whigs is by their actions. Yet one Observation ought to be made, and it is, that as the apostat Whigs of our time deserve to be mark'd with Infamy; so the leading Torys who formerly dipt their hands in the Blood of their fellow Citizens, or who were the principal Agents and Instruments of the Court, ought in my opinion to be excluded out of all Trust. Every body wou'd justly wonder to see those Judges now on the Bench, who then declar'd for the King's Will against our Laws, and implicitly serv'd all his purposes of Impoverishing, Inflaving, or Murdering his Subjects. But wou'd it not be as great wonder to [55] see any of King Charles's French Pensionors, or of King James's evil Counsillers, restor'd to Favoror Preferment in the present Government, which was set up not only to reform the disorders introducd by those persons, but also to prevent the like for the time to com. But as there is no danger of such a fatal error, so this is spoken only for Caution. Thus I have given an account how the Nation was divided in their Politics, and how both the Parties have bin plaid one against another, the better to subdue or destroy them. It will have this use for the future, that as oft as the like course is taken, we may guess what is meant by it, and consequently be prepar'd for our Defence : for, as the Proverb says, forewarn'd forearm'd.

[56]

CHAP. IV.

The Art of Governing by Parties in Parlament. ↩