JAMES TYRRELL,

A Brief Disquisition of the Law of Nature according to ... Cumberland (1692)

|

[Created: 10 June, 2023]

[Updated: June 13, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, A Brief Disquisition of the Law of Nature according to the principles and method laid down in the Reverend Dr. Cumberland's Latin treatise on that subject ... (London: Richard Balwin, 1692).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1692-Tyrrell_LawNature/Tyrrell_LawOfNature1692-ebook.html

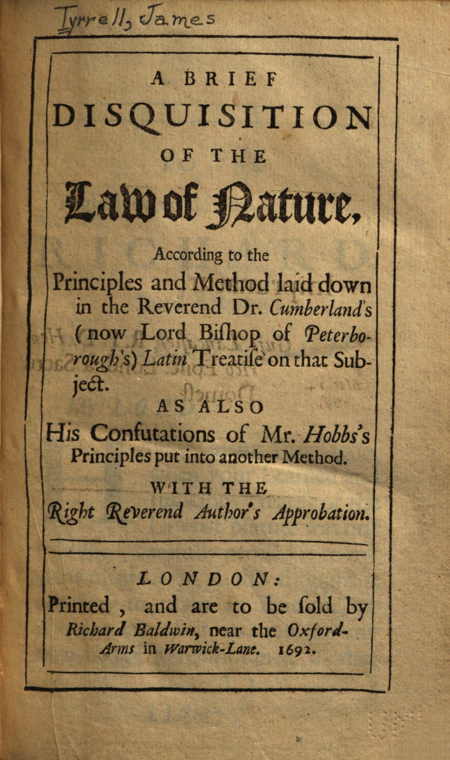

James Tyrrell, A Brief Disquisition of the Law of Nature, According to the Principles and Method laid down in the Reverend Dr. Cumberland's (now Lord Bishop of Peterborough) Latin Treatise on that Subject. As also His Confutations of Mr. Hobbs's Principles put into another Method. With the Right Reverend Author's Approbation. (London: Printed, and are to be sold by Richard Baldwin, near the Oxford-Arms in Warwick-Lane. 1692).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Table of Contents"

- TO THE Right Reverend Father in GOD, RICHARD, Lord Bishop of PETERBOROUGH. pp. iii-xvi

- THE PREFACE TO THE READER, By way of INTRODUCTION. pp. xvii-lvii

- TO THE BOOKSELLER. p. lviii-xil

- OF THE Law of NATURE, And its OBLIGATION. pp. 1-229

- [Analytical Table of Contents] pp. lx-lxxii

- The Contents of the First Chapter. p. lx

- The Contents of the Second Chapter. p. lxiii

- The Contents of the Third Chapter. p. lxvi

- The Contents of the Fourth Chapter. p. lxviii

- The Contents of the Fifth Chapter. p. lxxi

- CHAP. I. p. 1

- CHAP. II. p. 45

- CHAP. III. p. 104

- CHAP. IV. p. 148

- CHAP. V. p. 193

- [Analytical Table of Contents] pp. lx-lxxii

- THE HEADS OF THE SECOND PART. BEING A Confutation of Mr. H's Principles. pp. 231-249

- The Heads of the First Principle. p. 231

- The Heads of the Second Principle. p. 233

- The Heads of the Third Principle. p. 233

- Heads of the Fourth Principle. p. 235

- The Heads of the Fifth Principle. p. 237

- The Heads of the Sixth Principle. p. 239

- The Heads of the Seventh Principle. p. 241

- The Heads of the Eighth Principle. p. 244

- The Heads of the Ninth Principle. p. 245

- The Heads of the Tenth Principle. p. 247

- The Second Part: Wherein the Moral Principles of Mr. Hobb's De Cive & Leviathan, are fully Consid'red, and Confuted. pp. 251-396

- INTRODUCTION. p. 251

- PRINCIPLE I. p. 253

- PRINCIPLE II. p. 266

- PRINCIPLE III. p. 270

- PRINCIPLE IV. p. 277

- PRINCIPLE V. p. 297

- PRINCIPLE VI. p. 302

- PRINCIPLE VII. p. 315

- PRINCIPLE VIII. 358

- PRINCIPLE IX. p. 369

- PRINCIPLE X. p. 385

- Books Printed for Richard Baldwin. p. 397

[iii]

TO THE Right Reverend Father in GOD, RICHARD, Lord Bishop of PETERBOROUGH.↩

My LORD,

HAving, many Years agon, when your Learned and Judicious Treatise of the Laws of Nature was first published, carefully perused it to my great satisfaction, I also thought it necessary to make an Epitome, or Abridgment of it, as well for my own better Remembrance, as that [PB] I believed it might be also useful, as an Introduction to Ethicks, for some near Relations of mine, for whom I then designed it. These Papers, after they had lain by me several Years, I happened to shew to some Friends of mine, (and in particular to the Honourable Mr. Boyle;) who so well approved of the Undertaking, that they encouraged me to make it publick, as that which might give great satisfaction to those of the Nobility and Gentry of our own Nation, (as well as others of a lower rank) who either do not understand Latin, or else had rather read Epitomes of greater Works, than take the Pains to peruse the Originals. Which Task, tho' not very grateful to me, yet I was prevailed with to undertake, and to look over those Papers again, and add several considerable [PB] Passages out of the Treatise itself; and this not for Fame's sake, or the honour of being thought an Author, since I was satisfied, that nothing of that nature could be due to one, who does not pretend to more, than to Translate or Abridge another Man's Labours: Yet I am willing, in pursuance of your Lordship's Principle, to sacrifice all these little private Considerations to the Publick Good, as being sensible, that in the Trade of Learning (as in other Trades) divers, who cannot be Inventors, or chief Merchants, may yet do the Publick good service by venting other Mens Notions in a new dress; especially since I have also observed, that things of this kind, if well done, (and with due acknowledgment to the Authors from whence they are borrowed) as they have proved beneficial to [PB] those whose Education, or constant Employments in their own Professions, will not give them leave to peruse many Volumes, written perhaps in a Language they are no great Masters of; so also, they have not failed of some Commendation from all Candid Readers. Thus Monsieur Rohault's Abridgment of Des Cartes's Philosophy, and Monsieur Bernier's of Gassendus's, (to mention no more) have been received with general Applause, not only by all Ingenious Men of the French, but also of our own Nation, who understand that Language.

And the Learned and Inquisitive Dr. Burnet hath thought an Undertaking of this kind so useful for our Nobility and Gentry, as to give us his own elegant Translations, or rather Abridgments in English, of his two ingenious Treatises of the Theory [PB] of the Earth. And I doubt not, but your Lordship would have done somewhat in this kind, with this admirable Work of yours, had not the constant Employments of your Sacred Function, as well as your other severe and useful Studies, hindred you from it.

But, perhaps, it may be thought by some, that this Task hath been very well performed already by Dr. Parker, late Bishop of Oxford, in his Treatise, entituled▪ A Demonstration of the Laws of Nature, and therefore needs not be done over again. But to this I shall only say, that as he hath borrowed all that is new in that Work from your Lordship's Book, so it is with so slight an acknowledgment of that Obligation, that since he owns himself beholding to you for no more than the first Hint, or main Notion, no [PB] wonder if he hath fallen very short of the Original from whence he borrowed it, both in the clearness, as well as choice of the Arguments or Demonstrations, and in the particular setting forth of those Rewards and Punishments derived (by God's appointment) from the Nature of Men, and the Frame of Things; which can only be done according to that exact Method your Lordship hath there laid down. Tho', I confess, there is one thing that is particular in that Authors Undertaking, (viz.) That excellent Account he there gives us of the great Differences and Uncertainties among the most famous of the Heathen Philosophers, concerning Mans Soveraign Good, or Happiness, chiefly for want of the certain belief of a future state, and that clear conviction we now have, that Mens [PB] chiefest Good or Happiness consists in God's Love and Favour towards them: As also his observation, That, notwithstanding all that can be said of the Natural Rewards of Vertue, and Punishments of Vice, nothing but the reasonable hope and expectation of Happiness in a Life to come, can in all Cases bear us up under all the Miseries, Sorrows and Calamities of this. And herein I must own I agree with him; and therefore hope your Lordship will pardon me, if I have in the ensuing Discourse insisted somewhat more particularly upon these future Rewards and Punishments, which I doubt not may very well be proved from Reason, and the necessity of supposing them, in order to the asserting and vindicating God's Justice and Providence: Tho' I grant, that the Gospel, or Divine Revelation, hath given [PB] us more firm grounds for this our Belief, than we had before by the mere light of Nature.

But supposing this Work of Bishop Parker never so well performed; as I do not deny, but it hath all the advantages of a Popular and Gentile Stile, and that neat Turn he gives to all his Writings; and therefore I have not scrupled to transcribe, out of his Discourse, one or two Passages, where I thought either his way of urging your Lordship's Arguments, or the close summing them up, was not to be mended by any other Pen: Yet since (as I have already observed) the whole is not done from your Lordship's Work, and is also too concise, and full of Digressions, and besides wants your solid Confutations of Mr. H.'s Principles, it seems necessary, that another Treatise more exact in the [PB] kind, should be published as more agreeable to your Lordship's Original: Whether this which I now present you with, be such, I must submit to your Lordship's and the Reader's judgment.

But since I have undertaken this difficult Province with your Lordships approbation, it is fit, that I give you, as well as the Reader, some account of the Method I have followed in this Treatise, and wherein it differs from yours.

First then, to begin with the Preface, The substance of it is wholly yours, except the Introduction concerning the usefulness of the Knowledge of the true Grounds of the Law of Nature, in order to a right understanding of Moral Philosophy, nay Christianity itself.

But for a Conclusion to the Preface, I have also made some Additions, [PB] wherein. I have shewn your Principle of Endeavouring the Common Good, is not a new Invention, but that which several Great Men had before delivered, as the only firm Rule, by which to try not only all our Moral Actions, but all Civil Laws, whether they are right and just; that is, agreeable to right Reason, or not. And I have also concluded it with a set of Principles, very necessary to be understood, for the proving the Truth of all Natural Religion, and the Law of Nature, tho' the two last alone are the Subject of your Lordship's Book, as well as of my Abridgment of it.

But to speak more particularly of the Discourse itself, since I here design no more than an Epitome, I hope your Lordship will not take it ill, if I have omitted most of your rare [PB] Instances and Parallels drawn from the Mathematicks, many of which are above the capacity of common Readers, (tho' therein your Lordship hath shewn your self a Great Master) and have confined my self only to such plain and easie Proofs and natural Observations as Men of all capacities may understand. So also if in the Chapter of Humane Nature, I have left out divers curious Anatomical Observations, wherein the Structure of Mens Bodies differs from that of Beasts, if I thought they were at all questionable or doubtful, or such as did not directly tend to the proving, that Mens Bodies are fitted and ordained by God for the Prosecution of the Common Good of others of their own Kind, above all other Creatures.

[PB]

I have also made bold to contract the Chapters in your Work, into a lesser number, having disposed the substance of them into other places, or else quite omitted some, as not so necessary to our purpose: As for example, I have placed most of the Matter of the third Chapter, De bono naturali, partly in the explanation of the word Good, in our Description of the Law of Nature, in the third Chapter, reserving what remained of it to the second part for the Confutation of that Principle of Mr. H. That no Action is Good or Evil in the State of Nature. So likewise for the fourth Chapter, De Dictaminibus Practicis, I have set down the Substance of it (omitting the Mathematical Illustrations) in our second Chapter of Humane Nature. So also the sixth Chapter, [PB] entituled, De iis quae in Lege Naturali continentur. And the seventh and eighth, De Origine Dominii, & Virtutum Moralium. I have partly disposed the substance of them into the first Chapter of the Nature of Things, but chiefly into your fourth Chapter, reducing all the Laws of Nature, and Moral Vertues therein contained, into this one Principle, of Endeavouring the Common Good of Rational Beings. But as for your last Chapter, viz. that part of it which contains the Consectaria, or Consequences deducible from the foregoing Chapters, in relation to the Law of Moses, and all Civil Laws; I have made bold to omit, since it is plain enough, that all the Precepts of the Decalogue do tend either (in the first Table) to the Honour and Glory of God, in his commanding himself to be [PB] the sole Object of our Worship, and that without any Images of himself; or else (in the second Table) to our Duties towards others, wherein the highest Vertue and Innocence are prescribed. And so likewise, that all the Laws of the Supreme Civil Powers have no Authority, but as they pursue this Great Rule, or Law of Nature, of procuring the Common Good of Rational Beings; that is, the Honour and Worship of God, and the Peace and Happiness of their Subjects, and of Mankind in general: And whereas your Lordship hath here also solidly and briefly confuted many Gross Errors in Mr. H.'s Morals, as well as Politicks, some of those Confutations I have made use of in the second Part, viz. those that relate to that Author's Moral Principles, which, if they are false, [PB] his Politick ones will fall of themselves.

To conclude, I must beg your Lordships Pardon, if I have made bold to alter your Method, as to your Confutation of Mr. H.'s Principles. For whereas you have thought fit to do it in the Body of your Work, and as they occurred under the several Heads you treat of; since I perceiv'd the placing your Answers after that manner, did disturb the Connexion and Perspicuity of the Discourse, I thought it better to cast those Answers into a distinct part, digested under so many Heads, or Propositions, in the order in which they stand in Mr. H.'s Books, de Cive, and Leviathan, where the Reader, if he pleases, may compare what I have quoted out of him.

[PB]

And I hope your Lordship will not take it amiss in me, if (to render the Work more pleasant and grateful to common Readers, and that it may not look like a bare Translation) I have added several Notions and Observations, some of my own knowledge, and others out of History, and the Relations of Modern Travellers, concerning the Customs of those Nations commonly counted Barbarous, who yet by their amicable living together, without either Civil Magistrates, or written Laws, serve sufficiently to confute Mr. H.'s extravagant Opinion, That all Men by Nature are in a State of War.

I have likewise presumed to add those Aphorisms of Good and Evil contained in Bishop Wilkins's Treatise of Natural Religion, and Dr. Moor's Enchiridion Ethicum, that [PB] the Reader may see them all at once, tho' I confess they are most of them to be found (tho' dispersedly) in your Lordship's Work. I have also inserted some things, in answer to the Objections at the end of the first Part, out of that noble contemplative Philosopher, Mr. Lock's Essay of Humane Vnderstanding; since he proceeds upon the same Principles with your Lordship, and hath divers very new and useful Notions concerning the Manner of Attaining the Knowledge of all Truths, as well Natural, as Divine, and the Certainty we have of them.

But, I fear, I have trespass'd too much upon your Lordship's Patience, by so long an Epistle, and therefore shall conclude with my Prayers for your Lordship's Happiness and Health, since I am confident you cannot but prove more [PB] useful for the common good of our Church and State, in this high and publick Station to which Their Majesties have thought fit to call you, than you could have been in a more private Condition: And I hope your Lordship will look upon this Dedication as a small Tribute of Gratitude, which all the World must owe you for your Learned and not Common Undertakings, of which Obligation none ought to be (or indeed is) more sensible than,

My LORD,

Your Lordship's most faithful

and humble Servant,

JAMES TYRRELL.

[PB]

THE PREFACE TO THE READER, By way of INTRODUCTION.↩

I Suppose you are not ignorant, that the Study of Moral Philosophy, or the Laws of Nature, was preferred (by Plato, Aristotle, Socrates, and Tully, the wisest of the Heathen Philosophers) above all other knowledge, whether Natural or Civil, and that deservedly, as well in respect of its usefulness, as certainty, since it was to that alone (as most agreeable to the Natural Faculties of Mankind) that Men, before they were assisted by Divine Revelation, owed the Discovery of their [PB] Natural Duties, to God, themselves, and all others: as Cicero hath shewn us at large in those three excellent Treatises, De Officiis, De Finibus, and De Legibus. And tho' I grant we Christians have now clearer and higher Discoveries of all Moral Duties, by the Light of the Gospel, yet is the Knowledge of Natural Religion, or the Laws of Nature, still of great use to us, as well for the confirmation as illustration of all those Duties, since by their Knowledge, and the true Principles on which they are founded, we may be convinced, that God requires nothing from us in all the practical Duties of revealed Religion, but our reasonable Service; that is, what is really our own interest, and concerns our good and happiness to observe, as the best and most perfect Rule of Life, whether God had ever farther enforced them or not by any revealed Law. And tho' I do not deny, that our Saviour Jesus Christ hath highly advanced and improved these Natural Laws, by more excellent and refined Precepts of Humility, Charity, and Self-denial, than were discovered before by the wisest of the Heathen Philosophers, especially as to the greater assurance we have of that grand Motive to Religion and Vertue, the immortality of the Soul, or a Life either eternally happy or miserable, when this is ended: Yet certainly it was this Law of Nature, or [PB] Reason alone, by which Mankind was not only to live, but also to be judged, before the Law given to Moses, and it must be for not living up to this Natural Light, that the Heathens shall be condemned, who never yet heard of Christ, or of a revealed Religion, and so cannot (as St. Paul expresly declares to the Romans) believe on him of whom they have not heard, Rom. 10.14. And therefore the same Apostle, in the first Chapter of the same Epistle, appeals to the knowledge of God, from the things that are seen, that is, the Creation of the World, as the foundation of all Natural Religion, and their falling [notwithstanding this knowledge,] into that gross Idolatry they professed, as the only reason, why God gave them up to their own hearts lusts, because that when they knew God, they glorified him not as God, neither were thankful, but became vain in their imaginations, and their foolish heart was darkned, v 21. And so likewise in the second Chapter, the Apostle farther tells them, that when the Gentiles, who have not the Law, do by nature the things contained in the Law, these having not the Law, are a Law unto themselves, shewing the work of the Law written in their hearts; that is, the Law of Nature or Reason, as the main substance or effect of the Mosaical Law. And that it is by this Law alone, that they [PB] shall be judged, mark what immediately follows, Their consciences bearing witness, and their own thoughts (or reasonings, as it is rather to be rendred) in the mean while accusing or excusing each other. And indeed the Apostle supposes the Knowledge of God as a Rewarder of Good Works, as the foundation of all Natural, as well as revealed Religion, and the first Principle of saving Faith, as appears in his Epistle to the Hebrews, Chap. 11. v. 6. But without faith it is impossible to please him, for he that comes unto God must first believe that he is, and that he is a rewarder of all them that diligently seek him. But I need speak no more of Natural Religion, and how necessary it is to the true Knowledge of the Revealed, since the Reverend and learned Dr. Wilkins, Late Bishop of Chester, hath so well perform'd that Noble Vndertaking, in that excellent Posthumous Treatise, published by the Reverend Dr. Tillotson, now Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, to which nothing needs to be added by so mean a Pen as mine.

But since the Laws of Nature, as derived from God the Legislator, are the foundation of all Moral Philosophy and true Politicks, as being those which are appealed to in all Controversies between Civil Soveraigns, and also are the main Rules of those mutual Duties between [PB] Soveraigns and their Subjects: It is worth while to enquire how these Laws may be discovered to proceed from God as a Legislator. Now whereas this can only be done by one of these two ways, (viz.) Either from the certain and manifest Effects and Consequences that proceed from their observation; Or, 2dly, From the Causes from which they are derived. The former of these hath been already largely treated of by others, especially by the most learned Hugo Grotius, in his admirable Work, De Jure Belli & Pacis. And by his Brother William, in that small Posthumous Treatise, De Principiis Juris Naturalis. And by the Iudicious Monsieur Puffendorf, in his learned Treatise, De Jure Naturae & Gentium: As also by our own Countryman, Dr. Sharrock. Who have all undertaken to prove their certainty from their general belief and reception by the wisest and most civilized Nations in all Ages. To which we may also add the learned Mr. Selden, in that most elaborate Work, De Jure Gentium juxta placita Hebraeorum. And as I do acknowledge, that those Great Men have all deserved very well in their way, so I think none deserves greater commendation, than that excellent Work of Grotius the Elder, which as it was the first in its kind, so it is worthy of enduring as long as Vertue and Iustice shall be in esteem among Mankind. And [PB] tho' the Objections which are wont to be brought against this Method of proving the Laws of Nature, are not of so great moment, as to render it altogether fallacious or useless, as some would have it to be; yet I freely acknowledge they can chiefly serve to convince Men of sincere and honest minds, and who are naturally disposed to Vertue and right Reason: So that I conceive it were more useful, as well as certain, to seek for a firmer and clearer Demonstration thereof, from a strict search and inquisition into the Nature of things, and also of our own selves, by which I doubt not but we may attain not only to a true Knowledge of the Laws of Nature, but also of that true Principle on which they are founded, and from whence they are all derived.

But it will not consist with the narrow bounds of a Preface, to propose and answer all the Objections that may be made against their Method of proving the Law of Nature, from the Consent of Nations, neither perhaps can it be done at all to the universal satisfaction even of indifferent persons; since it may be still urged by those that do not admit them, that altho' some Dictates of Right Reason may be indeed approved of by our Vnderstandings, and are commonly received and practised by most Nations for their general usefulness and conveniency: Yet it must be acknowledged, that there [PB] is still required the Knowledge of God as a Legislator, by whose Authority alone they can obtain the force of Laws. The Proof of which (tho' the most material part of the Question) hath been hitherto omitted, or but slightly touch'd, by former Writers on this Subject.

But besides the Objections of some of the Ancients, Mr. Selden and Mr. Hobbs have also argued against this Method, tho' upon divers Principles, and from different Designs, the latter intending, that no body should receive these Dictates of Reason, as obligatory to outward Actions, before a Supreme Civil Power be instituted, who shall ordain them to be observed as Laws. And tho' he sometimes vouchsafes them that Title, yet in his De Cive, cap. 14. he tells us,

"That in the state of Nature they are but improperly called so, and that tho' the Laws of Nature may be found largely described in the Writings of Philosophers, yet are they not for this cause to be called Laws, any more than the Writings or Opinions of Lawyers are Laws, till confirmed and made so by the Supreme Powers."

But, on the other side, Mr. Selden more fairly finds fault with the want of Authority in these Dictates of Reason, (considered only as such) that he may from hence shew us a necessity of recurring to the Legislative Power [PB] of God, and that he may thereby make out, that those Dictates of Reason do only acquire the force of Laws, because all our knowledge of them is to be derived from God alone, who when he makes these Rules known to us, does then (and not before) promulgate them to us as Laws. And so far I think he is in the right, and hath well enough corrected our common Moralists, who are wont to consider these Dictates of Reason as Laws, without any sufficient proof, that they have all the Conditions required to make them so, viz. That they are established and declared to us by God as a Legislator, who hath annexed to them sufficient Rewards and Punishments. But I think it is evident, that if these Rational Dictates can by any means be proved to proceed from the Will of God, the Author of Nature, as Rules for all our Moral Actions, they will not need any Humane Authority, much less the Consent or Tradition of any one or many Nations to make them known to be so: Therefore, tho' I grant this learned Author hath taken a great deal of pains to prove from divers general Traditions of the Iewish Rabbins, that God gave certain Commands to Adam, and after to Noah, contained in these seven Precepts, called by his Name; and that those various Quotations this learned Author hath there produced, do clearly prove, that the Iews believe, that [PB] all Nations whatever, altho' they do not receive the Laws of Moses, yet are obliged to observe the same Moral Laws, which they conceive to be all contained under the Precepts above mentioned; and tho' this Work is indeed most learnedly and judiciously performed, and may prove of great use in Christian Theology, yet I must confess it still seems to me, that he hath not sufficiently answered his own Objection concerning Mens Ignorance, or want of Discovery of the Law-giver; for altho' it should be granted, that those Traditions they call the Precepts of Noah, should be never so generally or firmly believed by the whole Iewish Nation, yet are they not therefore made known to the rest of Mankind, and one of them, viz. That of not eating any Part or Member of a living Creature, is justly derided and received with scorn by all other Nations. So that it seems evident to me, that the unwritten Traditions of the learned Men of any one Nation, cannot be looked upon as a sufficient promulgation made by God as a Law-giver, of those Laws or Precepts therein contained; and that all Nations, who perhaps have never heard of Adam or Noah, should be condemned for not living according to them, especially when we consider, that it is but in these latter Ages of the World, that the Iewish Rabbins began to commit these Traditions to Writing; and that it is most [PB] probable the ancient Iews knew nothing of them, since neither Josephus, nor Philo Judaeus, take any notice of these Precepts in their Writings.

Therefore that the Divine Authority of those Dictates of Right Reason, or Rules of Life, called the Laws of Nature, may more evidently be demonstrated to all considering Men, it seemed to me the best and fittest Method to inquire first into their Natural Causes, as well internal as external, remote as near, since by this Series of Causes and Effects, we may at last be more easily brought to the knowledge of the Will of God, their first Cause, from whose intrinsick Perfections and extrinsick Sanctions, by fit Rewards and due Punishments, we have endeavoured to shew, that as well their Authority as Promulgation is derived.

I know indeed, that the greatest part of former Writers have been content, to suppose, that these Dictates of Reason, and all Acts conformable thereunto, are taught us by Nature, or at most do only affirm in general, that they proceed from God, without shewing us which way, or the manner how. Therefore it seemed highly necessary to us, that we ought to inquire more exactly how the force of Objects from without, and of our own Notions or Idea's from within us, do both concur towards the [PB] imprinting, and fixing these Principles in our Minds, as Laws derived from the Will of God himself; which Work if it be well performed, we hope may prove of great use, not only to our own Nation, but to all Mankind; because from hence it may appear, both by what means Men's Vnderstandings, may attain to a true, and natural Knowledge of the Divine Will, or Laws of God; So that if they practise them not, they may be left without excuse: And this Principle will likewise serve for a general Rule, by which the Municipal Laws of every Common-wealth may be tryed, whether they are Iust, and Right, or not; that is agreeable with the Laws of Nature, and so may be corrected, and amended by the supreme Powers, when-ever they have deviated from this great End of the common Good. And from hence may also be demonstrated, that there is somewhat in the Nature of God, as also in our own, and all other Men's Natures, which administers present Comfort and Satisfaction to our Minds, from good Actions, as also firm Hopes, or Presages of a future Happiness, as a Reward for them when this Life is ended; whereas on the other side the greatest Misery, and most dismal Fears, do proceed from wicked, or evil Actions, from whence the Conscience seems furnished, as it were with Whips, and Scorpions [PB] to correct and punish all Vice, and Improbity: So that it may from hence appear, that Men are not deluded in their moral Notions, either by Clergy-men, or Politicians.

I grant, the Platonists undertake to dispatch all these Difficulties a much easier way, only by supposing certain innate Idea's of moral Good, and Evil, imprest by God upon the Souls of Men. But I must indeed confess my self not yet so happy, as to be able thus easily to attain to so great a Perfection, as the Knowledge of the Laws of Nature by this natural Instinct, or Impression: And it doth not seem to me either safe, or convenient to lay the whole Stress of Natural Religion, and Morality upon an Hypothesis, which hath been exploded by all Philosophers, except themselves, and which can never alone serve to convince those of Epicurean Principles, for whom we chiefly design this Work: But whosoever will take the Pains to peruse, what hath been written, against these innate Idea's by the inquisitive, and sagacious Dr. Ioh. Lock. Author of the late Essay of humane Understanding, will find them very hard, if not impossible to be proved to have ever been innate in the Souls of Men, before they came into the World: Therefore as I shall not take upon me, absolutely to deny the Being, or Impossibility of such Idea's, so I shall not make use of any Arguments [PB] drawn from thence in this Discourse, Though I heartily wish that any Reasons, or Motives, which may serve to promote true Vertue, and Piety may prevail as far as they deserve, with all sincere and honest Men.

And the same Reasons, which deterred me from supposing any natural Laws innate in our Minds, have also made me not presently suppose, as many do (without any due proof) That such Idea's have existed in the Divine Intellect from all Eternity. And therefore I looked upon it as more proper, and necessary to begin from those things, which are most known, and familiar to us by our Senses, and from thence to prove that certain Propositions of immutable Truth prescribing our Care of the Happiness, or common Good of all rational Agents considered together, are necessarily imprinted upon our Minds from the Nature of things, and which the first Cause perpetually determines so to act upon them: And that in the Terms of these Propositions, are intrinsecally included an evident Declaration of their Truth, and certainty, as proceeding from God the first Cause in the very intrinsick Constitution of things: From whence it will be also manifest, that such practical Propositions are truly and properly Laws, as being declared, and established by due Rewards, and Punishments annexed to them by him, as the supreme Legislator.

[PB]

But after it shall appear, that the Knowledge of these Laws, and a Practice conformable to them are the highest Perfection, or most happy State of our Rational Natures: It will likewise follow, that a Perfection Analogous to this Knowledge, and a Practice conformable to these Laws, must necessarily be in the first Cause; from whence proceeds, not only our own Natural Perfections, but also the most wise Ordination of all Effects without us, for the common Conservation, and Perfection of the whole Natural System, or Vniverse, which our Eyes daily behold: For that is look'd upon by me among the things most certainly prov'd, That it must be first known, what Iustice is, and what those Laws enjoyn, in whose Observation all Iustice consists, before we can distinctly know, that Iustice is to be attributed to God, and that his Iustice is to be considered by us as a Pattern, or Example for us to imitate. Since we do not know God by an immediate Intuition of his Essence, or Perfections, but only from the outward Effects of his Providence, first known by our Senses, and Experience: Neither is it safe to affix Attributes to him, which we cannot sufficiently understand, or make out from things without us.

Having now shewn you in general, the difference between our Method, and that which [PB] others have hitherto followed, it is fit we here declare, in as few words as we can, the chief Heads of those things which we have delivered in this Treatise. Supposing therefore those natural Principles concerning the Laws of Motion, and Rest sufficiently demonstrated by Naturalists (especially such as depend upon Mathematical Principles) since we have only here undertaken to demonstrate the true Grounds of Moral Philosophy, and to deduce them from some supposed Knowledge of Nature, and as they refer to our Moral Practice; I have here therefore supposed all the Effects of corporeal Motions, which are natural and necessary, and performed without any Intervention of humane Liberty, to be derived from the Will of the first Cause. And, 2dly. (which Mr. H. himself likewise in his Leviathan admits) that from the Consideration, and Inquisition into these Causes, and from the Powers, and Operations of natural Bodies, may be discovered the Existence of one Eternal, Infinite, Omnipotent Being, which we call God.

So that every Motion impress'd upon the Organs of our Senses, whereby the Mind is carried on to apprehend things without us, and to give a right Iudgment upon them, is a natural Effect; which by the Mediation of other inferiour Causes, owes its Original to the [PB] first Cause. From whence it follows, that God by these natural Motions of Causes, and Effects delineates the Idea's, or Images of all natural and moral Actions on our Minds; And that the same God, after he hath thus made us draw various Notions, from the same Objects, does then excite us to compare them with each other, and then joyn them together, and so determines us to form true Propositions of the things, thus singly received and understood. So that sometimes a thing is exposed whole, and all at once to our View, and sometimes it is more naturally considered successively; or according to its several parts; And the Mind thereby perceives that the Notion of awhole, signifies the same, with that of all the several Idea's of the particular parts put together, and so is thence carried on to make a Proposition of the Identity of the whole, with all its parts. And can truly affirm, that the same Causes, which preserve the whole, must also conserve all its constituent parts; and then from a diligent Contemplation of all these Propositions, (which may justly challenge the Title of the more general Laws of Nature;) we may observe, that they are all reduceable to one Proposition; from whose fit, and just Explication, all the Limits, or Exceptions, under which the particular Propositions are proposed, may be sought for, and [PB] discovered, as from the Evidence of that one Proposition, which may be reduced into this, or the like Sence, (viz.) The endeavour as far as we are able of the common good of the whole System of Rational Beings conduces, as far as lies in our Power to the good of all its several Parts or Members, in which our own Felicity is also contained as part thereof; Whereas the Acts opposite to this Endeavour, do bring along with them Effects quite opposite thereunto, and will certainly procure our own Ruine, or Misery at last. Therefore the whole Summ of this Proposition, may be reduced to these three Things. 1. That which concerns the Matter of it, to wit, the Knowledge of its Terms drawn from the Nature of Things. 2. Its form, (viz.) the Connexion of those Terms contained in this practical Proposition, and particularly such, which because of the Rewards, and Punishments annexed to them, may make it deserve to be called a Divine, Natural Law, as proceeding from God the Authour of Nature. Or, 3. The Deduction of all other natural Laws from this, as their Foundation, and Original, from that Respect, or Proportion they bear to the common Good, or happiest State of the whole aggregate Body of Rational Beings.

But as to the Explication of the Terms of this Proposition: I hope the Reader will [PB] not be scandaliz'd, that we attribute Reason to God, and have reckoned him as the Head of Rational Beings, since we do not thereby mean, that Sort of Reason which consists in deducing Conclusions from prior Propositions, but rather that absolute Omniscience, and perfect Wisdom, which we understand to be in God, which Cicero himself could not better describe, than by the Name of Adulta Ratio; or, the most perfect Reason. And if we Mortals can know, or apprehend any aright, thing of him, it is as we do partake of some part, though in an infinitely lower Degree of that only true Knowledge, and Vnderstanding. So that if we can once rightly judge, that the common Good of Rational Beings, is the greatest of all others; it is no doubt true, and no otherwise true, than as it is so apprehended by the Divine Intellect; As when it is demonstrated to us, that the three Angles of a Triangle, are equal to two right ones, no doubt, but the Deity it self, had before the same Idea of it. So likewise if we have affirmed, that we can contribute any thing to the good, and happiness of rational Beings, by our Benevolence towards them, and so may seem to suppose, that there is a certain good common to us, and the Deity▪ and which we may some way serve to promote: We desire to be understood not as if we imagin'd, that by our testifying [PB] our Love, and Honour towards God, in any internal, or external Acts of Worship; we could add, or contribute any thing to his infinite Happiness, and Perfections; but only as judging it more gratefull, and agreeable to his Nature, if by our Deeds we express our Gratitude and Obedience to him, by imitating him in our Care of the common good of Mankind, than if we deny his Being, or blaspheme his Attributes, and violate, or contemn his Laws: So likewise, if in our Thoughts, Words and Actions, we express our Worship, and Love towards him, we doubt not but it is more pleasing, and agreeable to his Divine Nature, than if by the contrary Actions we should signifie our neglect, or hatred of him. For if we abstractively compare any two rational Natures together, we must acknowledge a greater Similitude, when one of them agrees, and co-operates with the other, than if we should suppose a Disagreement or Discord between them, or that the End or Design intended by the one should be crossed, or opposed by the other. Neither do I see what can hinder, but that the same may be affirmed, if one of these rational Natures be supposed to be God, and the other only Man. Therefore, as it is known by our common Sense, that it is more gratefull to any Man to be beloved, and honoured, than to be hated, and contemned. So [PB] it may be found by a manifest Analogy of reason, that it is more gratefull to God, the Head of rational Beings to be belov'd, and honour'd by the Service and Worship of us Men, than to be hated, and contemned. For as the Desire of being beloved argueth no Imperfection in us; so likewise in God, it is so far from giving the least Suspicion thereof, that on the contrary, it rather argues his Goodness, since our Natures are perfected, to the highest Degree they are capable of, by our Love to him, and Obedience to his Commands. So that, when we speak of any Good, common to us with the Divine Nature, it is only to be understood Analogically; for those things which we perceive to conserve, or perfect our own Nature we call gratefull to us, that is, as they render the Mind pleased, and full of Ioy, Pleasure, and Satisfaction: And though we confess we cannot contribute any thing to the infinite Perfection of the Deity, Yet since this Ioy, or Complacency proceeding from our Love, and Service towards him may be conceived without any Imperfection, they I think may be safely attributed to his Divine Nature, and look'd upon as a sort of good endeavoured by us for him, since God esteems our Love, and Service as the only Tribute we can pay him, and therefore he hath inseparably annexed the highest Rewards to this Love of [PB] himself (as shall be proved in this following Discourse) which certainly he would never have done, unless it had been his Will, that we should thus love, and worship him. So that though I grant, that the Divine Good or Happiness is not at all advanced by our Worship of him; yet will not this at all derogate from our definition of endeavouring the Common good of Rational Beings, which may be made out by these following Considerations.

1. That all Rational Beings, or Agents are, and must be considered together, as naturally, and necessarily constituting one intellectual System, or Society; because they agree together, to prosecute one chief End, Viz. The good of the Vniverse, or World, especially of that intellectual System; by the fittest Means applicable to that End since, whilst they are truly rational, they cannot differ in judging what is that best End; nor avoid chusing the same necessary Means, leading thereunto.

2. That although God, the Head of this intellectual System, be indeed uncapable of any Addition to his infinite Happiness, and Perfection, yet the whole System (in as much as it includes all finite rational Beings) is capable of Improvement in these its finite parts, which Improvement God cannot only desire, but ever did, and will promote both by his own Power, as also by that of all subordinate voluntary Agents, [PB] whereby God's Essential Goodness becomes manifest to us: And the good of the whole System may reasonably be judged as grateful, or pleasing to God the head thereof, although it can add nothing to himself: thus in Embryons all the other Members daily grow, and improve, after the Head or Brain is supposed to have attained its full bigness.

These voluntary, or free Actions of the subordinate Agents, when they concur with God's wisdom and goodness, are naturally and evidently known to be more pleasing (as being rewarded by him) than malevolent Actions opposite to this chief end, which fight both against God and Men; nor does the consideration of God's rewarding such good Actions, imply any addition to his Divine Perfections. So that our Benevolence towards God, and consequently, our worship of him, is but our free acknowledgment, that he naturally, and essentially is (what he ever was and will be) the same infinite, good, and wise Disposer, and Governour of the whole System of rational Beings; and this our benevolence by giving him Glory, Love, Reverence, and Obedience fulfils all the Duties of humanity towards those of our own kind, which answers both the Tables of the moral, or natural Law; and in this consent of our minds with the divine Intellect, consists that compleat harmony of the Vniverse of intellectual Beings.

[PB]

The great influence of these Principles upon all the parts of natural Religion, may be more fully express'd and made out; by these following considerations.

1. The voluntary acknowledgment and consent of our minds to the Perfections of the divine Nature and Actions, include the agreement, and concurrence of our chief Faculties, viz. The understanding, and will, therewith; and moreover, naturally excite all our Affections to comply with them, and so strongly dispose us in our future Life, and Actions, to compose our selves to the imitation thereof, to the utmost of our Abilities; particularly these Principles naturally produce in us. First, Praises, and Thanksgivings to God, private and publick, for goods already done to our selves, or others, wherein the Essence of Prayer is contained.

2. Hence also arise Hope, Affiance, or Trust in God, which I willingly acknowledge is fullest of assurance, when founded not only on observations, or past experience of Providence; but hath also revealed promises annex'd, relating to future Good. 3. To conclude, when our Acknowledgment, and high esteem of the divine Attributes move us to the imitation thereof, we must needs thereby arise to those high degrees of Charity, or the endeavour of the greatest publick good which [PB] we observe in God to prosecute, and such Charity imports not only exact Iustice to all, but that overflowing bounty, tenderness and sympathy with others, beyond which humane Nature cannot arrive; because these not only harmoniously consent with the like Perfections in God, but also co-operate with him, to the improvement of the finite parts of the rational System, whereof he is the infinite, yet Sympathizing head, who declares he takes all that is done to the Members of this intellectual Society, as done to himself.

Nevertheless, I profess my self to understand this Sympathy, or compassion in God in such a Sence only, as it is understood in Holy Writ, for that infinite concern for the good of his best Creatures, which is contained in his infinite goodness, and is a real perfection of his Nature, not implying any mistake of others for himself, nor any capacity of being lessened or hurt by the power of any mans malice, but yet fully answers, (nay infinitely exceeds) that solicitous care, and concern for the good of others, which Charity and Compassion work in the best of men.

In short, if the Reader will take the pains to peruse the Three first Chapters of this Discourse, he will find, that we have, in explaining the terms of this Proposition, not only given a bare interpretation of Words, but also [PB] have proposed the true Notions, and Natures of those things, from whence they are taken; as far as is necessary for our purpose, and may observe that by one, and the same labour we have directly, and immediately explained the Power, and necessity of those humane Actions, which are required to the common Happiness of all men, and also to the private good, and necessity of particular Persons. Altho' it seemed most convenient to use such general words, which may in some Sence be attributed to the Divine Majesty, and to have done it with that Design, that by the help of this Analogy thus supposed, not only our obligation to Piety and Vertue, but also the Nature of Divine Iustice, and Dominion may be from hence better understood.

But as for what concerns the form of this Proposition it is evident, that it is wholly practical, as that which determines concerning the certain effects of humane Actions. But it is also to be noted, that altho' the words, conduces, or renders, in either of these Propositions, are put in the present Tense; Yet it is not limited to any time present, but abstracts from it: And because its truth doth chiefly depend upon the Identity of the whole, with the parts; it is as plainly true of all future time, and is as often used by us in this Discourse with respect to future, as well as present [PB] Actions. And therefore this Proposition is more fit for our purpose, because built upon no particular Hypothesis; for it doth not suppose men born in a Civil State, nor yet out of it, neither see any Kindred or Relation to be among men, as derived from the same common Parents, as we are taught by the Holy Scriptures; since the obligation of the Laws of Nature is to be demonstrated to those who do not yet acknowledge them: Neither on the other side doth it suppose, (as Mr. H. doth in his de Cive) a great many men already grown, and sprung up out of the Earth like Mushrooms; But our Proposition, and all those things which we have deduced from it, might have been understood, and acknowledged by the first Parents of mankind, if they had only considered themselves together with God, and their Posterity which was to come into the world. Neither may it less easily be understood and admitted by those Nations, which have not yet heard of Adam and Eve.

Neither may it be amiss to observe, concerning the Sence of this Proposition, that in the same words in which the Cause of the greatest, and best effect is laid down, there is also delivered in short the means to the chiefest end, because the effect of a rational Agent, after it is conceived in its mind, and that it hath determined to bestow its endeavours [PB] in producing it, is called the End, and the Acts, or Causes by which it endeavours to effect it, are called the means; and from this observation, may be shown a true method of reducing all those things which Moral Philosophers have spoken about the means to the best end, into natural Theorems concerning the Power of humane Actions, in producing such Effects; and in this form, they may more easily be examined whether they are true, or not, and may be more evidently demonstrated so to be; and also we may hence learn by the like Reason, how easily all true knowledge of the force of those natural Causes, which we may any way apply to our use, does suggest fit Mediums for the attaining of the end intended, and so may be applyed to Practice according to occasion: Lastly, from thence it appears, that either of these Propositions, which we have now laid down, do so far approach to the nature of a Law, as they respect an end truly worthy of it, viz. The common good of all rational Beings; or else (if you please to word it otherwise) the Honour, or Worship of God, conjoyned with the common Good, and Happiness of mankind.

And tho' it doth not yet appear, that this Proposition is a Law, because the Lawgiver is not yet mentioned, nevertheless I doubt not but you will find in the Body of this Discourse, that it hath all [PB] things necessary to render it so, viz. God, considered as a Legislator, and his Will or Commands sufficiently declared to us, as a Law from the very constitution of our Natures, as also of other things without us; and likewise established by sufficient Rewards, and Punishments both in this life, and the next; neither do we suppose it can be more evidently proved, that God is the Author of all things, than that he is also the Author of this Proposition, concerning the common good of rational Beings, or concerning his own Honour, and Worship conjoyned with the common Good of mankind: And tho' I confess we have been more exact, and have dwelt longer upon the Rewards, that we may expect from the observation of this Law, than upon the Punishments, which are appointed for the breach of it; and tho' I know the Civilians have rather placed the Sanction of Civil Laws in Punishments, than Rewards; yet I hope we have not offended, tho' we a little deviate from their Sense, and make it part of the Sanction of this Law, that it is established by Rewards, as well as Punishments; since it seems more agreeable to the Nature of things, whose foot-steps are strictly to be followed, to consider the positive Idea's of Causes, and Effects in our minds, and which do not receive either Negations, or Privations by our outward Senses; and our Affections [PB] ought rather to be moved by the Love, or Hopes, of a present, or future Good; than by the Fear, or hatred of the contrary Evil: For as no man is said to Love, Life, Health, and those grateful motions of the Nerves, or Spirits which are called corporeal Pleasures, because he may avoid Death, Sickness, or Pain; but rather from their own intrinsick Goodness, or Agreeableness with our humane Natures; so likewise no rational Man desires the Perfections of the mind, to wit, the more ample and distinct knowledge of the most noble Objects, the most happy State of rational Beings, can only give him; and all this, not only that he▪ may avoid the mischiefs of Ignorance, Envy, and Malevolence; but because of that great Happiness, which he finds by experience to spring from such vertuous Actions, and Habits, and which render it most ungrateful to us, to be deprived of them; and so the Causes also of such Privations are judg'd highly grievous, and troublesome: From whence it also appears, that even Civil Laws themselves, when they are established by Punishments, (e. g.) by the fear of Death, or loss of Goods, (if we consider the thing truly) do indeed force men to yield obedience to them from the love of Life, or Riches; which they find can only be preserved by their observation. So that the avoiding of Death, and Poverty is but in other words, love [PB] of Life, and Riches; as he who by two Negatives would say he would not want Life, means no more, but that he desires to enjoy it: To which we may likewise add, that Civil Laws themselves ought to be considered from the end which the Law-makers regard in making them, as also which all good Subjects design in observing them; to wit, the publick Good of the Commonwealth (part of which is communicated to all of them in particular, and so brings with it a natural Reward of their obedience,) rather than from the Punishments they threaten, by whose fear some only are deterred from violating them; and those of the worst, and most wicked sort of Men.

But tho' we have shewn, that the Sum of all the Precepts or Laws of Nature, as also of the Sanctions annexed to them, are briefly contained in this Proposition; yet its Subject, is still but an endeavour to the utmost of our Power, of the common Good of the whole System of rational Beings, this limitation of the utmost of our Power implies, that we do not think our selves capable of adding any thing to the Divine Perfections which we willingly acknowledge to be beyond our Power. So that here is at once exprest both our Love towards God, and Good will to mankind, who are the constituent parts of this System. But the Predicate of this Proposition is, that which conduces to the [PB] good of all its singular Parts, or Members, and in which our own Happiness, is contained as one part thereof. Since all those good things, which we can do for others, are but the Effects of this endeavour: so that the Sum of all those Goods (of which also our own Felicity consists) can never be mist of either in this Life, or a better, as the Reward of our obedience thereunto. So to the contrary Actions, Misery in this Life, or in that to come, are the Punishments naturally due. But the Connexion of the Predicate with the Subject, is both the Foundation of the truth of this Proposition; and also a Demonstration of the natural Connexion, between this obedience, and the Rewards, as also between the Transgression, and the Punishments.

From whence the Readers will easily observe, the true Reason for which this practical Proposition, and all others which may be drawn from thence, do oblige all rational Creatures to know, and understand it; whilst other Propositions (suppose Geometrical ones) tho' found out by right Reason, and so are Truths proceeding from God himself, yet do not oblige men to any Act, or Practice pursuant to them; but may be safely neglected by most Men, to whom the Science of Geometry may not be necessary; whereas the Effects of the endeavour of the common Good, do intimately concern the Happiness of all mankind, (upon whose joynt or [PB] concurrent Wills, and Endeavours, every single mans Happiness doth after some sort depend) so that this Endeavour, can by no means be neglected without endangering the losing all those hopes of Happiness, which God hath made known to us, from our own Nature and the Nature of things; and so hath sufficiently declared the Connexion of Rewards and Punishments, with all our Moral Actions, from whose Authority, as well this general Proposition, as all others, which are contained in it, must be understood to become Laws.

So that from the terms of this Proposition, it is apparent, that the adequate, and immediate effect of our thus acting, and concerning which this Law is established; is whatever is grateful to God, and beneficial to Men, that is, the natural Good of all the parts of the whole System of rational Beings; Nay further, is the greatest of all Goods, which we can imagine, or perform for them; since it is greater than the like good of any particular part, or Member of the same System. And farther, it is thereby sufficiently declared, that the Felicity of particular Persons, is derived from this happy State of the whole System; as the Nutrition of any one Member of an Animal is produced by a due Distribution of the whole Mass of Blood diffused through all the parts of the Body. From whence it appears, that this Effect must needs [PB] be the best, since it shews us, that not the private Felicity of any single Man is the principal end of God the Legislator, or ought to be so of any one, who will truly obey his Will; and by a Parity of reason it also appears, that those humane Actions, which from their own natural force, and Efficacy are apt to promote the common Good, are certainly better, than those which do only serve the private Good of any one Man, and that by the same proportion, as a common Good is greater than a private: So likewise those Actions, which take the nearest way to attain this effect as an End, are called Right, because of their natural Similitude with a right or straight line, which is always the shortest between the two Terms. But the same Actions, when compared with a Natural, or positive Law, as a rule of Life, or Manners, and are found conformable to it, are called morally good, and also right; that is, agreeable to the Rule, but the Rule it self is called right, or straight, as it shews the nearest way to the End. But I shall referr you for the clearer Explication of these things, to what we have farther said concerning them in the Discourse its self, especially in the Second part, wherein we prove against Mr. H's Principle, that there is a true Natural, and Moral Good antecedent to Civil Laws.

[PB]

But however, it may not be amiss to give you in short the method which we take to prove, that this Law of endeavouring the common Good, is really and indeed, and not Metaphorically a Law. 1. This general Supposition being premised, That all particular Persons who can either promote or oppose this common Good are parts of that whole Body of mankind, which is either preserved, or prejudiced by their endeavours. We shall not now descend to the particular Proofs as they are drawn from the Causes of such Actions of which we have partly treated in the Chapter of humane Nature, and partly from their natural Effects and Consequences, of which we have largely discoursed, in the Chapter of the Obligation of the Law of Nature; as also in the Second part in our Observation on Mr. H's Principles; all which may nevertheless be reduced to these plain Propositions. 1. As I have observed it is manifest, that our Felicity, or highest Reward is essentially connected by God the Legislator, with the most full, and constant exercise of our natural Powers employed about the noblest Objects, and greatest Effects they can be capable of as proportioned to them; from whence it may be gathered, that all men endued with these Faculties are naturally obliged under the penalty of losing, or missing of this their Happiness, to exercise those Powers about [PB] the worthiest Objects, (viz.) God, and Mankind. Nor can it be long doubted, whether our Faculties may be more happily exercised in maintaining Friendship, or Enmity with them; for I, think it is certain, there can be no Neutral State in which God and Men, can neither be beloved, nor hated; or in which we can stand so far Neuters, as neither to do things gratefull, nor ungratefull to them. But if it be granted, that there is a manifest Necessity (if we will be truly happy) of preserving Amity both with God and Men, here is thereby presently declared the Sanction of this general Law of Nature, which we are now enquiring into, for this alone establishes all Natural Religion, and also all those things, which are necessary to the Happiness and preservation of Mankind, which are, besides Piety towards God, 1. A peaceable Commerce and Agreement of divers Nations, which are treated of by the Law of Nations, which is but a Branch or subordinate Member of this great Law of Nature. 2. The Constitution, and Conservation of a Civil Society, or Common-wealth, which is the Scope of all Civil Laws. And, 3. The Continuance of Domestick Relations, and private Friendships, concerning which the general Rules of Ethicks, as also the more particular ones of Oeconomies do prescribe. And therefore, we have put together [PB] many things in the Chapter of humane Nature, by which all particular Persons of sound Minds are some way rendred capable of so large a Society, and are either more nearly, or remotely disposed to it. And we do here intreat the Reader, that he will not consider those things, each of them singly, or apart, but all together; since from all of them conjoyned, he may raise a sufficient Argument to prove the Existence, and evince the Sanction of this most general Law of Nature, and that Men will necessarily fail of their Happiness, which chiefly consists in the Adequate, or proper Exercise of their rational Faculties, unless they will exercise them in cultivating this Amity, or Love both with God, and Men; to which Ends they are before all other Animals particularly adapted.

But from the Effects of such Actions conducing to the Common good of Rational Beings, we have also further shewn in the Chapter of the Obligation of the Laws of Nature, that this Sanction by sufficient Rewards, and Punishments, is most commonly connected with such Actions. And it is manifest, that in the first place God, as the best and wisest of Rational Beings is to be loved, and honoured by such Actions or Endeavours, as that the Goods, and Fortunes of all innocent Persons of what Nation soever, are thereby secured as far as [PB] lies in our Power, and all things profitable for particular Persons, procured according to the Proportion they bear to the good of the whole Body of Mankind; so that this Law will not permit any thing to be done, which the Care of the whole doth not allow: Nor can any thing be supposed more worthy a rational Creature, and from whence greater Effects can proceed, than a Will always propeuse towards the good of this whole Body governed by the Conduct of a Right Vnderstanding.

Therefore, since it can certainly be foreknown, that such Effects will follow from this Endeavour, no Man can be ignorant that all the Ioys, and present Comforts of true Piety, are therein contained, together with the hopes of a blessed Immortality, besides those many Conveniencies of Peace, and commerce with those of other Nations, and all those Emoluments both of Civil, and Domestick Government, and private Friendships which are connected with this Endeavour, as the common Rewards thereof, and which cannot by any Means within our Power be otherwise obtained. So that, he who neglects the Care of the Common good, doth also reject the true Causes of his own Felicity, and embraces those of his Misery, as a Punishment due to his Folly. In short, since it is manifest from the Nature of things, that the highest Happiness which we can procure for our [PB] selves, proceeds from our Care both of Piety to God, and Love and Peace with Men. And that the Endeavour of these can only be found in his Soul, who truly studieth the common Good of all Rational Beings, it is also evident, that the greatest Rewards, that any one can acquire, are necessarily connected with this Endeavour, and that the Loss, or Deprivation of this Felicity, doth necessarily adhere as a Punishment to the opposite Actions. The former of these, which declares the true Causes of all that Felicity, which particular Persons can thereby obtain, we have proved from Natural Effects found by Experience. The latter, (viz.) that Piety to God, and Charity or Benevolence towards all Men, are contained in the Endeavour of the common Good; and we have also proved in the fourth Chapter, that all Vertues, both private and publick, are contained in this Endeavour.

But because the Connexion of Rewards and Punishments, which follow those Acts which are for the common Good, or opposite to it, is something obscured by those Evils which often befall good Men, and those good Things which too frequently happen to Evil ones, it is enough to our Purpose to shew, that notwithstanding all these the Connexion between them is so sufficiently constant, and manifest in the Nature of things, that from thence may be [PB] certainly gathered the Sanction of the Law of Nature, commanding the former, and prohibiting the latter Actions. And we may suppose those Punishments to suffice for its Sanction, which, (all things rightly weighed) much exceed the Gain that may arise from any Act done contrary to this Law. But in comparing of the Effects which do follow good Actions on one hand, and Evil ones on the other those good, or evil Things ought not to be reckoned in to the Account, which either cannot be acquired, or avoided by any humane Prudence, or Industry; such as are those which proceeding from the Natural Necessity of External Causes, may happen to any one by mere Chance, which are wont to fall out alike, both to good and bad. Therefore we shall only take those into our Account, which may be foreseen and prevented by humane Foresight, as some way depending upon our own Wills or Acts.

But I must also acknowledge, that these Effects do not all depend upon our own particular Powers, but many of them do also proceed from the good Will and Endeavours of other Rationals; yet since it may be known from their Natures, as they are, is agreeable to our own, that the common Good is the best, and greatest End which they can propose to themselves, and that their Natural Reason requires that they should act for an End, and rather for this [PB] than any other less good, or less perfect: And that it is moreover known by Experience, that such Effects of Vniversal Benevolence, may be for the most part obtained from others, by our own benevolent Actions; it is just that those Effects should be numbred or esteemed among those Consequences, which do for the most part so fall out, because every Man is esteemed able to do whatever he can perform, or obtain by the Assistance of others. So that the whole Reward which is connected to good Actions, by the natural Constitution of Things, is somewhat like those Tributes of which the publick Revenues consist, which do not only arise out of constant Rents, but also out of divers contingent Payments, such as Custom, or Excise upon Commodities, whose value, although it be very great, yet is not always certain, though they are often farmed out, at a certain Rate. Therefore in the reckoning up of these Rewards, not only those parts thereof ought to come into Account, which immutably adhere to good Actions, such as are that Happiness, which consists in the Knowledge and Love of God, and good Men, the absolute Government of our Passions, the sweet Harmony, and Agreement betwixt the true Principles of our Actions, and all the parts of our Lives, the Favour of the Deity, and the Hopes of a blessed Immortality proceeding from all these: But there ought [PB] also to be taken into the Account, all those Goods, which do, (though contingently) adhere to them, and which may either happen to us from the good Will of others, or flow from that Concord, and Society, which is either maintained between divers Nations, or those of the same Common-wealth; and which we do as far as we are able, procure for our selves by such benevolent Actions. And by the like Reason, we may also understand of what particulars all that Misery, or those Punishments may consist, which is connected with those Acts, that are hurtfull to the common Good.

So that all of us may learn from the Necessity of the Condition in which we are born, and live, to esteem contingent Goods; and to be drawn to act by the Hopes of them; for the Air it self, which is so necessary for our subsistence, and Preservation doth not always benefit our Bloud, or Spirits, but is sometimes infected with deadly Steams, and Vapours: Nor can our Meat, Drink or Exercise always preserve our Lives, but do often generate Diseases. And Agriculture it self doth not always pay the Husband-man's Toyl with the expected Gain, but sometimes he even loses by it. And sure we are not less naturally drawn to the Endeavour of the common Good, than we are to such natural Actions from the Hope of a Good, that may but probably proceed from them. But [PB] how justly we may hope for a considerable Return from all others, joyntly considered, for all our Labours bestowed upon the common Good; we shall be able to make the best Account of, when we consider what our own Experience, and the History of all Nations for the time past, may teach us to have befallen those who have either regarded, or despised this great End.

But because the whole Endeavour of this common Good, contains no more but the Worship of the Deity, the Care of Fidelity, Peace, and Commerce betwixt Nations, and the instituting, and maintaining Government both Civil and Domestick, as also particular Friendships, as the parts thereof taken together, it is manifest, that the Endeavour thereof exprest by a mutual Love and Assistance must in some Degree be found among all Nations, as necessary to their own Happiness and Preservation: Nay, it seems farther manifest to me, that those who attain but to the Age of Manhood do owe all those past Years, much more to the Endeavour of others bestowed upon the common Good, than to their own Care, which in their tender Age was almost none at all. For we then do altogether depend upon, and owe our Preservation to that Obedience, which others yield as well to Oeconomical Precepts, as to all Laws both Civil and Religious, which do wholly proceed from this Care of the common Good. Whereas [PB] it is certain, that if afterwards we expose our Lives to danger, Yea, if we lose them for the publick Good, we should lose far less for its sake, than we did before receive from it; for we do then only lose the uncertain Hopes of future Enjoyments, whereas it is certain that scarce so much as the Hope of them can remain to particular Persons where the common Good is destroyed, for we have thence received the real Possession of all those Contentments of Life, with which we are blest: And therefore we are bound in Gratitude, as well as by Interest, to return those again whenever they are lawfully required of us; though I grant (for the Honour of the Gospel) that the firmest Encouragements, and greatest Reward we Men can have for exposing, nay, losing our Lives for the Benefit, or Service of the Commonwealth, is that Happiness we may justly expect in another Life after this.

These things seem evident to us, as resembling that Method whereby we are naturally taught, that the Health, and Strength of our whole Body is preserved by the good Estate of its particular Members, in its receiving Food, and Breath: Although sometimes Diseases may breed within the Body, or divers outward Accidents (as Wounds, Bruises, and the like) do happen to it from without, which may hinder [PB] the particular Members from receiving that Nourishment, which is necessary for them: And we are taught after the same Manner by the Acts, immediately promoting the common good, that the Happiness of particular Men, (which are the Members of this natural System) may no less certainly be expected, nor are less naturally derived from thence, than the Strength of our Hands doth proceed from the due State of the whole Mass of Bloud, and nervous Iuice: Though we confess that many things may happen, which may cause this general Care of the whole Body of Mankind, not always to meet with the good Effect we desire; so that particular Persons may certainly, infallibly enjoy all the Felicity they can hope for, or expect: Yet this is no Argument against it, any more than that the taking in of Air, and Aliments, (however necessary for the whole Body) should prevent all those Accidents, and Distempers it is subject to, since it may happen as well by the violent, and unjust Actions of our fellow Subjects, (like the diseased Constitution of some inward part) or by the Invasion of a foreign Enemy (like a Blow, or other outward Violence) that good Men may be deprived in this Life of some Rewards of their good Deeds, and may also suffer divers outward Evils; Yet since these [PB] are more often repelled by the Force of Concord, and Civil Government, or are often shook off after some short Disturbances, either by our own private Power, or else by that of the Civil Sword, as Diseases are thrown off by a healthfull Crisis, or Effort of Nature. So that notwithstanding all these Evils, Men are more often recompenced with greater Goods, partly from the Assistance of others, but chiefly from that of Civil Government, or else of Leagues made with Neighbouring States: From whence it is that Mankind hath never been yet destroyed; notwithstanding all the Tyranny and Wars, that Men's unreasonable Passions have exercised, and raised in the World, and that Civil Governments, or Empires, have been more lasting than the most long lived Animals. From all which it is apparent, that the deprived Appetites of divers Men, or those Passions which do often produce Motions so opposite to the common Good, ought no more to hinder us from acknowledging the Natural Propensions of all the rest of Mankind (considered together) to be more powerfully carried towards that which we every Day see may be procured thereby, (viz.) The Conservation and farther Perfection of the whole Body of Mankind, than that divers Diseases breeding in the parts of Animals, or any outward Violence should hinder us from [PB] acknowledging, that the Frame of their Bodies, and the Natural Function of their parts are fitted, and intended by God, for the Conservation of Life, and the Propagation of their Species.

But that we may carry on this Similitude, (between a living Body and its particular Members, with the whole Body of Mankind, and all the Individuals contained under it,) a little farther, I will here give you Monsieur Pascal's Excellent Notion concerning this common Good, as it is published in those Fragments, Vide Chap. des Pensees Morales. Entituled, Les Pensees de Monsieur Pascal, since it both explains and confirms our Method.

‘He there supposes, That God having made the Heavens, and the Earth, and divers other Creatures, not at all sensible of their common Happiness, would also make some rational Beings which might know him, and might make up one Body consisting of rational Members; and that all Men are Members of this Body, so that it is necessary to their happiness, that all particular Men, as Members of this Body, conform their particular Wills to the Vniversal Will of God, that governs the whole Body, as the Head or Soul thereof. And though it often happens, that one Man falsly supposes himself an independent Being, and so will make himself [PB] the only Centre of all his Actions; yet he will at last find himself whilst in this State, (separated from the Body of rational Beings, and who not having any true Principle of Life, or Motion, doth nothing but wander about) distracted in the uncertainty of his own Being; but if ever he comes to a true knowledge of himself, he will find, that he is not that whole Body, but only a small Member of it, and hath no proper Life, and Motion, but as he is a part thereof: So that to regulate our Self-love, every Man ought to imagine himself, but one small part of this Body of Mankind, composed of so many intelligent Members, and to know what Proportion of Love every Man oweth himself, let him consider what Degree of Love the Body bears to any one small single part, and so much Love, that part (if it had sense) ought to bestow upon it self, and no more: All Self-love that exceeds this is unjust.’

So far this sagacious contemplative Gentleman thought long since, though I confess he doth not proceed to shew in what manner the Good of every individual Person depends upon the Happiness of the whole Body of Mankind, as our Author hath here done; though no doubt, he was excellently well fitted to do it, if he had lived to reduce those excellent Thoughts, into a set Discourse.

[PB]