JOHN LOCKE,

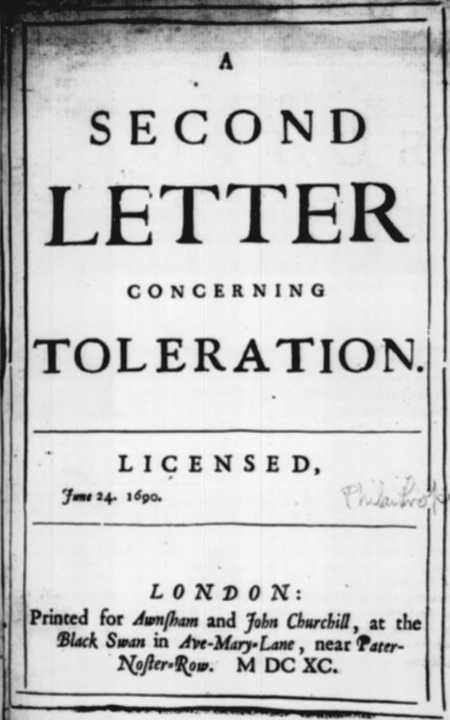

A Second Letter on Toleration (1690)

|

[Created: 8 March, 2024]

[Updated: 12 March, 2024] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, A Second Letter concerning Toleration (London : Printed Awnsham and John Churchill, at the Black Swan in Ave-Mary-Lane, near Pater-Noster-Row, MDCXC 1690).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1690-Locke_Toleration2/Locke_Toleration1690-ebook.html

Philanthropus (John Locke), A Second Letter concerning Toleration (London : Printed Awnsham and John Churchill, at the Black Swan in Ave-Mary-Lane, near Pater-Noster-Row, MDCXC 1690).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

TO THE AUTHOR OF THE Argument of the Letter concerning Toleraration, briefly considered and answered.

SIR,

YOU will pardon me if I take the same Liberty with you, that you have done with the Author of the Letter concerning Toleration; to consider your Arguments, and endeavour to shew you the Mistakes of them. For since you have so plainly yeilded up the Question to him, and do own that the Severities he would disswàde Christians from, are utterly unapt, Pag. 12, 13, 14. and improper to bring Men to imbrace that Truth which must save them; I am not without some hopes to prevail with you, to do that your self, which you say is the only justifiable Aim of Men differing about Religion, even in the use of the severest Methods: viz. Carefully and impartially to weigh the whole matter, and thereby to remove that Prejudice which makes you yet favour some Remains of Persecution: Promising my self that so ingenious a Person will either be convinced by the Truth which appears so very clear and evident to me; or else confess, that, were either you or I in Authority, we should very unreasonably and very unjustly use any Force upon the other which differ'd from him, upon any pretence of want of Examination. And if Force be not to be used in your case or mine, because unreasonable, [2] or unjust; you will, I hope, think fit that it should be forborn in all others, where it will be equally unjust and unreasonable; as I doubt not but to make it appear it will unavoidably be, where ever you will go about to punish Men for want of Consideration. For the true way to try such Speculations as these, is to see how they will prove when they are reduc'd into Practice.

The first thing you seem startled at, in the Author's Letter, is the largeness of the Toleration he proposes: And you think it strange that he would not have so much as a Pagan, Mahometan, Pag. 1. or Jew, excluded from the Civil Rights of the Commonwealth, because of his Religion. We pray every day for their Conversion, and I think it our Duty so to do: But it will, I fear, hardly be believed that we pray in earnest, if we exclude them from the other ordinary and probable means of Conversion; either by driving them from, or persecuting them when they are amongst us. Force, you allow, is improper to convert Men to any Religion. Toleration is but the removing that Force. So that why those should not be tolerated as well as others, if you wish their Conversion, I do not see. But you say, it seems hard Pag. 2. to conceive how the Author of that Letter should think to do any Service to Religion in general, or to the Christian Religion, by recommending and perswading such a Toleration. For how much soever it may tend to the Advancement of Trade and Commerce, (which some seem to place above all other Considerations) I see no reason, from any Experiment that has been made, to expect that true Religion would be a gainer by it; that it would be either the better preserved, the more widely propagated, or rendred any whit the more fruitful in the Lives of its Professors by it. Before I come to your Doubt it self, Whether true Religion would be a gainer by such a Toleration; give me leave to take notice, that if, by other Considerations, you mean any thing but Religion, your Parenthesis is wholly besides the matter; and that if you do not know that the Author of the Letter places the Advancement of Trade above Religion, your Insinuation is very uncharitable. But I go on.

You see no reason, you say, from any Experiment that has been made, to expect that true Religion would be a gainer by it. True Religion and Christian Religion are, I suppose, to you and me, the same thing. But of this you have an Experiment in its first appearance in [3] the World, and several hundreds of Years after. It was then better preserv'd, more widely propagated (in proportion) and render'd more fruitful in the Lives of its Professors, than ever since; tho then Jews and Pagans were tolerated, and more than tolerated, by the Governments of those places where it grew up. I hope you do not imagine the Christian Religion has lost any of its first Beauty, Force, or Reasonableness, by having been almost 2000 Years in the World; that you should fear it should be less able now to shift for it self, without the help of Force. I doubt not but you look upon it still to be the Power and Wisdom of God for our Salvation; and therefore cannot suspect it less capable to prevail now, by its own Truth and Light, than it did in the first Ages of the Church, when poor contemptible Men, without Authority, or the countenance of Authority, had alone the care of it. This, as I take it, has been made use of by Christians generally, and by some of our Church in particular, as an Argument for the Truth of the Christian Religion; that it grew and spread, and prevailed, without any Aid from Force, or the Assistance of the Powers in being. And if it be a mark of the true Religion, that it will prevail by its own Light and Strength; (but that false Religions will not, but have need of Force and foreign Helps to support them) nothing certainly can be more for the advantage of true Religion, than to take away Compulsion every where. And therefore it is no more hard to conceive how the Author of the Letter should think to do Service to Religion in general, or to the Christian Religion, than it is hard to conceive that he should think there is a true Religion, and that the Christian Religion is it; which its Professors have always own'd not to need Force, and have urged that as a good Argument to prove the truth of it. The Inventions of Men in Religion need the Force and Helps of Men to support them. A Religion that is of God wants not the Assistance of Human Authority to make it prevail. I guess, when this dropp'd from you, you had narrow'd your Thoughts to your own Age and Country: But if you will enlarge them a little beyond the Confines of England, I do not doubt but you will easily imagine that if in Italy, Spain, Portugal, &c. the Inquisition; and in France their Dragooning; and in other parts those Severities that are used to keep or force Men to the National Religion, were taken away; and instead thereof the Toleration [4] propos'd by the Author were set up, the true Religion, would be a gainer by it.

The Author of the Letter says, Truth will do well enough, if Pag. 49. she were once left to shift for her self. She seldom hath received, and he fears never will receive much Assistance from the Power of great Men, to whom she is but rarely known, and more rarely welcome. Errors indeed prevail, by the Assistance of Foreign and borrowed Succours. Truth makes way into our Vnderstanding by her own Light, and is but the weaker for any borrowed Force that Violence can add to her. These words of his (how hard soever they may seem to you) may help you to conceive how he should think to do Service to True Religion, by recommending and perswading such a Toleration as he proposed. And now, pray tell me your self, whether you do not think True Religion would be a gainer by it, if such a Toleration establish'd there, would permit the Doctrine of the Church of England to be freely preached, and its Worship set up, in any Popish, Mahometan, or Pagan Country? If you do not, you have a very ill Opinion of the Religion of the Church of England, and must own that it can only be propagated and supported by Force. If you think it would gain in those Countries, by such a Toleration, you are then of the Author's Mind, and do not find it so hard to conceive how the recommending such a Toleration might do Service to that which you think True Religion. But if you allow such a Toleration useful to Truth in other Countries, you must find something very peculiar in the Air, that must make it less useful to Truth in England. And 'twill savour of much partiality, and be too absurd, I fear, for you to own, that Toleration will be advantagious to True Religion all the World over, except only in this Island; Though, I much suspect, this, as absurd as it is, lies at the bottom; And you build all you say upon this lurking Supposition, that the National Religion now in England, back'd by the Publick Authority of the Law, is the only True Religion, and therefore no other is to be tolerated. Which being a Supposition equally unavoidable, and equally just, in other Countries, (unless we can imagine that every where but in England Men believe what at the same time they think to be a Lie) will in other Places exclude Toleration, and thereby hinder Truth from the means of propagating it self.

What the Fruits of Toleration are, which in the next words you [5] complain do remain still among us, and which you say give no Encouragement to hope for any Advantages from it; what Fruits, I say, these are, or whether they are owing to the want or wideness of Toleration among us, we shall then be able to judg, when you tell us what they are. In the mean time, I will boldly say, that if the Magistrates will severely and impartially set themselves against Vice, in whomsoever it is found; and leave Men to their own Consciences, in their Articles of Faith, and Ways of Worship; True Religion will be spread wider, and be more fruitful in the Lives of its Professors, than ever hitherto it has been, by the imposition of Creeds and Ceremonies.

You tell us, that no Man can fail of finding the Way of Salvation, Pag. 7. who seeks it as he ought. I wonder you had not taken notice, in the places you quote for this, how we are directed there to the right way of seeking. The words (John vii. 17.) are; If any Man will do his Will, he shall know of the Doctrine whether it be of God. And, Psalm XXV. 9, 12, 14. which are also quoted by you, tell us, The Meek will he guide in Judgment, and the Meek will he teach his Way. What Man is he that feareth the Lord, him shall he teach in the Way that he shall chuse. The Secret of the Lord is with them that fear him, and he will shew them his Covenant. So that these places, if they prove what you cite them for, that no Man can fail of finding the Way of Salvation, who seeks it as he ought; they do also prove that a good Life is the only way to seek as we ought; and that therefore the Magistrates, if they would put Men upon seeking the way of Salvation as they ought, should, by their Laws and Penalties, force them to a good Life; A good Conversation being the readiest and surest way to a right Understanding. Punishments and Severities thus apply'd, we are sure, are both practicable, just, and useful. How Punishments will prove in the way you contend for, we shall see when we come to consider it.

Having given us these broad Marks of your Good-will to Toleration, you tell us, 'Tis not your Design to argue against it, but Pag. 3. only to enquire what our Author offers for the proof of his Assertion. And then you give us this Scheme of his Argument.

1. There is but one Way of Salvation, or but one True Religion.

2. No Man can be saved by this Religion, who does not believe it to be the True Religion.

[6]

3. This Belief is to be wrought in Men by Reason and Argument, not by outward Force and Compulsion.

4. Therefore all such Force is utterly of no use for the promoting True Religion, and the Salvation of Souls.

5. And therefore no Body can have any Right to use any Force or Compulsion, for the bringing Men to the True Religion.

And you tell us, the whole strength of what that Letter urged for the Purpose of it, lies in this Argument; Which I think you have no more reason to say, than if you should tell us, that only one Beam of a House had any strength in it, when there are several others that would support the Building, were that gone.

The purpose of the Letter is plainly to defend Toleration, exempt from all Force; especially Civil Force, or the Force of the Magistrate. Now if it be a true Consequence, that Men must be tolerated, if Magistrates have no Commission or Authority to punish them for Matters of Religion; then the only strength of that Letter lies not in the unfitness of Force to convince Mens Vnderstanding. Vid. Let. p. 7.

Again; If it be true that Magistrates being as liable to Error as the rest of Mankind, their using of Force in Matters of Religion, would not at all advance the Salvation of Mankind, (allowing that even Force could work upon them, and Magistrates had Authority to use it in Religion) then the Argument you mention is not the only one, in that Letter, of strength to prove the Necessity of Toleration. V. Let. P. 8. For the Argument of the unfitness of Force to convince Mens Minds being quite taken away, either of the other would be a strong proof for Toleration. But let us consider the Argument as you have put it.

The two first Propositions, you say, you agree to. As to the Third, Pag. 4. you grant that Force is very improper to be used to induce the Mind to assent to any Truth. But yet you deny that Force is utterly useless for the promoting True Religion, and the Salvation of Mens Souls; which you call the Author's 4th Proposition: But indeed that is not the Author's 4th Proposition, or any Proposition of his, to be found in the Pages you quote, or any where else in the whole Letter, either in those terms, or in the sense you take it. In the 8th Page, which you quote, the Author is shewing that the Magistrate has no Power, that is not Right, to make use of Force in Matters of Religion, for the Salvation of Mens Souls. And the reason he gives for it there, is, because force has no efficacy, [7] to convince Mens Minds; and that without a full perswasion of the Mind, the Profession of the true Religion it self is not acceptable to God. Vpon this ground, says he, I affirm that the Magistrate's Power extends not to the establishing any Articles of Faith, or Forms of Worship, by the force of his Laws. For Laws are of no force at all without Penalties; and Penalties in this case are absolutely impertinent, because they are not proper to convince the Mind. And so again, Pag. 27. which is the other place you quote, the Author says; What soever may be doubted in Religion, yet this at least is certain; that no Religion which I believe not to be true, can be either true, or profitable unto me. In vain therefore do Princes compel their Subjects to come into their Church-Communion, under the pretence of saving their Souls. And more to this purpose. But in neither of those Passages, nor any where else, that I remember, does the Author say that it is impossible that Force should any way, at any time, upon any Person, by any Accident, be useful towards the promoting of true Religion, and the Salvation of Souls; for that is it which you mean by utterly of no use. He does not deny that there is any thing which God in his Goodness does not, or may not, sometimes, graciously make use of, towards the Salvation of Mens Souls (as our Saviour did of Clay and Spittle to cure Blindness) and that so, Force also may be sometimes useful. But that which he denies, and you grant, is that Force has any proper Efficacy to enlighten the Understanding, or produce Belief. And from thence he infers, that therefore the Magistrate cannot lawfully compel Men in matters of Religion. This is what the Author says, and what I imagine will always hold true, whatever you or any one can say or think to the contrary.

That which you say is, Force indirectly and at a distance may do Pag. 5. some Service. What you mean by doing Service at a distance, towards the bringing Men to Salvation, or to imbrace the Truth, I confess I do not understand; unless perhaps it be what others, in propriety of Speech, call by Accident. But be it what it will, it is such a Service as cannot be ascribed to the direct and proper Efficacy of Force. And so, say you, Force, indirectly, and at a distance, may do some Service. I grant it: Make your best of it. What do you conclude from thence, to your purpose? That therefore the Magistrate may make use of it? That I deny. That such an indirect, and at a distance Vsefulness, will authorize the Civil Power in the use of it, that will never be prov'd. Loss of Estate [8] and Dignities may make a proud Man humble: Sufferings and Imprisonment may make a wild and debauched Man sober: And so these things may indirectly, and at a distance, be serviceable towards the Salvation of Mens Souls. I doubt not but God has made some, or all of these, the occasions of good to many Men. But will you therefore infer, that the Magistrate may take away a Man's Honour, or Estate, or Liberty, for the Salvation of his Soul; or torment him in this, that he may be happy in the other World? What is otherwise unlawful in it self (as it certainly is to punish a Man without a fault) can never be made lawful by some Good that, indirectly and at a distance, or if you please, indirectly and by accident, may follow from it. Running a Man through may save his Life, as it has done by chance, opening a lurking Imposthume. But will you say therefore that this is lawful, justifiable Chirurgery? The Gallies, 'tis like, might reduce many a vain, loose Protestant, to Repentance, Sobriety of Thought, and a true sense of Religion: And the Torments they suffer'd in the late Persecution, might make several consider the Pains of Hell, and put a due estimate of Vanity and Contempt on all things of this World. But will you say, because those Punishments might, indirectly and at a distance, serve to the Salvation of Mens Souls, that therefore the King of France had Right and Authority to make use of them? If your indirect and at a distance Serviceableness may authorize the Magistrate to use Force in Religion, all the Cruelties used by the Heathens against Christians, by Papists against Protestants, and all the persecuting of Christians one amongst another, are all justifiable.

But what if I should tell you now of other Effects, contrary Effects, that Punishments in matters of Religion may produce; and so may serve to keep Men from the Truth and from Salvation? What then will become of your indirect, and at Pag. 5. a distance Vsefulness? For in all Pleas for any thing because of its usefulness, it is not enough to say as you do (and is the utmost that can be said for it) that it may be serviceable: But it must be considered not only what it may, but what it is likely to produce: And the greater Good or Harm like to come from it, ought to determine of the use of it. To shew you what Effects one may expect from Force, of what usefulness it is to bring Men to imbrace the Truth, be pleas'd to read what you [9] your self have writ. I cannot but remark, say you, that these Pag. 13. Methods (viz. depriving Men of their Estates, Corporal Punishments, starving and tormenting them in Prisons, and in the end even taking away their Lives, to make them Christians) are so very improper in respect to the Design of them, that they usually produce the quite contrary Effect. For whereas all the use which Force can have for the advancing true Religion, and the Salvation of Souls, is (as has already been shewed) by disposing Men to submit to Instruction, and to give a fair hearing to the Reasons which are offer'd for the enlightning their Minds and discovering the Truth to them; These Cruelties have the Misfortune to be commonly look'd upon as so just a Prejudice against any Religion that uses them, as makes it needless to look any further into it; and to tempt Men to reject it, as both false and detestable, without ever vouchsafing to consider the rational Grounds and Motives of it. This Effect they seldom fail to work upon the Sufferers of them. And as to the Spectators, if they be not beforehand well instructed in those Grounds and Motives, they will be much tempted likewise, not only to entertain the same Opinion of such a Religion, but withal to judg much more favourably of that of the Sufferers; who, they will be apt to think, would not expose themselves to such Extremities, which they might avoid by compliance, if they were not throughly satisfied of the Justice of their Cause. Here then you allow that taking away Mens Estates or Liberty, and Corporal Punishments, are apt to drive away both Sufferers and Spectators, from the Religion that makes use of them, rather than to it. And so these you renounce. Now if you give up Punishments of a Man, in his Person, Liberty, and Estate, I think we need not stand with you, for any other Punishments may be made use of. But, by what follows, it seems you shelter your self under the name of Severities. For moderate Punishments, as you call them in another place, you think may be serviceable; indirectly, and at a distance serviceable, to bring Men to the Truth. And I say, any sort of Punishments disproportioned to the Offence, or where there is no fault at all, will always be Severity, unjustifiable Severity, and will be thought so by the Sufferers and By-standers; and so will usually produce the Effects you have mentioned, contrary to the Design they are used for. Not to profess the National Faith, whilst one believes it not to be true; not to enter into Church-Communion with the Magistrate, as long as one judges the Doctrine there professed to [10] be erroneous, or the Worship not such as God has either prescribed, or will accept; this you allow, and all the World with you must allow, not to be a fault. But yet you would have Men punished for not being of the National Religion; that is, as you your self confess, for no fault at all. Whether this be not Severity, nay so open and avow'd Injustice, that Pag. 14. it will give Men a just Prejudice against the Religion that uses it, and produce all those ill Effects you there mention, I leave you to consider. So that the name of Severities in opposition to the moderate Punishments' you speak for, can do you no Service at all. For where there is no Fault, there can be no moderate Punishment: All Punishment is immoderate, where there is no Fault to be punished. But of your moderate Punishment we shall have occasion to speak more in another place. It suffices here to have shewn, that, whatever Punishments you use, they are as likely to drive Men from the Religion that uses them, as to bring them to the Truth; and much more likely; as we shall see before we have done: And so, by your own Confession, they are not to be used.

One thing in this Passage of the Author, it seems, appears absurd to you; that he should say, That to take away Mens Lives, to make them Christians, was but an ill way of expressing a Design of their Salvation. I grant there is great Absurdity some where in the case. But it is in the Practice of those who, persecuting Men under a pretence of bringing them to Salvation, suffer the Temper of their Good-will to betray it self, in taking away their Lives. And whatever Absurdities there be in this way of proceeding, there is none in the Author's way of expressing it; as you would more plainly have seen, if you had looked into the Latin Original, where the words are Vita denique ipsâ privant, ut fideles, ut salvi siant (Pag. 5.) which tho more literally, might be thus render'd, To bring them to the Faith and to Salvation; yet the Translator is not to be blamed, if he chose to express the Sense of the Author, in words that very lively represented the extream Absurdity they are guilty of, who under pretence of Zeal for the Salvation of Souls, proceed to the taking away their Lives. An Example whereof we have in a neighbouring Country, where the Prince declares he will have all his Dissenting Subjects sav'd, and pursuant thereunto has taken away the Lives of many of them. For thither at [11] last Persecution must come: As I fear, notwithstanding your talk of moderate Punishments, you your self intimate in these words; Not that I think the Sword is to be used in this Pag. 23. business, (as I have sufficiently declared already) but because all coactive Power resolves at last into the Sword; since all (I do not say, that will not be reformed in this matter by lesser Penalties, but) that refuse to submit to lesser Penalties, must at last fall under the stroke of it. In which words, if you mean any thing to the busines in hand, you seem to have a reserve for greater Punishments, when lesser are not sufficient to bring Men to be convinced. But let that pass.

You say, If Force be used, not instead of Reason and Arguments, Pag. 5. that is, not to convince by its own proper Efficacy, which it cannot do, &c. I think those who make Laws, and use Force, to bring Men to Church-Conformity in Religion, seek only the Compliance, but concern themselves not for the Conviction of those they punish; and so never use Force to convince. For, pray tell me; When any Dissenter conforms, and enters into the Church-Communion, is he ever examined to see whether he does it upon Reason, and Conviction, and such Grounds as would become a Christian concern'd for Religion? If Persecution (as is pretended) were for the Salvation of Mens Souls, this would be done; and Men not driven to take the Sacrament to keep their Places, or to obtain Licenses to sell Ale, (for so low have these holy Things been prostituted) who perhaps knew nothing of its Institution; and considered no other use of it but the securing some poor secular Advantage, which without taking of it they should have lost. So that this Exception of yours, of the use of Force, instead of Arguments, to convince Men, I think is needless; those who use it, not being (that ever I heard) concern'd that Men should be convinced.

But you go on in telling us your way of using Force, only to Pag. 5. bring Men to consider those Reasons and Arguments, which are proper and sufficient to convince them; but which, without being forced, they would not consider. And, say you, Who can deny but that, indirectly, and at a distance, it does some Service, towards bringing Men to imbrace that Truth, which either through Negligence they would never acquaint themselves with, or through Prejudice they would reject and condemn unheard? Whether this way of Punishment is like to increase, or remove Prejudice, we have already seen. And what [12] that Truth is, which you can positively say, any Man, without being forced by Punishment, would through carelesness never acquaint himself with, I desire you to name. Some are call'd at the third, some at the ninth, and some at the eleventh hour. And whenever they are call'd, they imbrace all the Truth necessary to Salvation. But these slips may be forgiven, amongst so many gross and palpable Mistakes, as appear to me all through your Discourse. For Example: You tell us that Force used to bring Men to consider, does indirectly, and at a distance, some Service. Here now you walk in the dark, and endeavour to cover your self with Obscurity, by omitting two necessary parts. As, first, who must use this Force: which, tho you tell us not here, yet by other parts of your Treatise 'tis plain you mean the Magistrate. And, secondly, you omit to say upon whom it must be used; who it is must be punished: And those, if you say any thing to your purpose, must be Dissenters from the National Religion, those who come not into Church-Communion with the Magistrate. And then your Proposition in fair plain terms will stand thus. If the Magistrate punish Dissenters, only to bring them to consider those Reasons and Arguments which are proper to convince them; who can deny but that indirectly, and at distance, it may do Service, &c. towards bringing Men to embrace that Truth which otherwise they would never be acquainted with? &c. In which Proposition, 1. There is something impracticable. 2. Something unjust. And, 3. Whatever Efficacy there is in Force (your way apply'd) to bring Men to consider and be convinced, it makes against you.

1. It is impracticable to punish Dissenters, as Dissenters, only to make them consider. For if you punish them as Dissenters (as certainly you do, if you punish them alone, and them all without exception) you punish them for not being of the National Religion. And to punish a Man for not being of the National Religion, is not to punish him only to make him consider; unless not to be of the National Religion, and not to consider, be the same thing. But you will say the design is only to make Dissenters consider; and therefore they may be punished only to make them consider. To this I reply; It is impossible you should punish one with a design only to make him consider, whom you punish for something else besides want of Consideration; or if you punish him whether he consider or no; as you do, if [13] you lay Penalties on Dissenters in general. If you should make a Law to punish all Stammerers; could any one believe you, if you said it was designed only to make them leave Swearing? Would not every one see it was impossible that punishment should be only against Swearing, when all Stammerers were under the penalty? Such a proposal as this, is in it self, at first sight, monstrously absurd. But you must thank your self for it. For to lay penalties upon Stammerers, only to make them not swear, is not more absurd and impossible than it is to lay Penalties upon Dissenters only to make them consider.

2. To punish Men out of the Communion of the National Church, to make them consider, is unjust. They are punished because out of the National Church: And they are out of the National Church, because they are not yet convinced. Their standing out therefore in this State, whilst they are not convinced, not satisfied in their Minds, is no Fault; and therefore cannot justly be punished. But your method is, Punish them, to make them consider such Reasons and Arguments as are proper to convince them. Which is just such Justice, as it would be for the Magistrate to punish you for not being a Cartesian, only to bring you to consider such Reasons and Arguments as are proper and sufficient to convince you: When it is possible, 1. That you being satisfied of the truth of your own Opinion in Philosophy, did not judg it worth while to consider that of Des Cartes. 2. It is possible you are not able to consider, and examine, all the Proofs and Grounds upon which he endeavours to establish his Philosophy. 3. Possibly you have examined, and can find no Reasons and Arguments proper and sufficient to convince you.

3. What ever indirect Efficacy there be in Force, apply'd by the Magistrate your way, it makes against you. Force used by the Magistrate to bring Men to consider those Reasons and Arguments, which are proper and sufficient to convince them, but which without being forced they would not consider; may, say you, be serviceable indirectly, and at a distance, to make Men imbrace the Truth which must save them. And thus, say I, it may be serviceable to bring Men to receive and imbrace Falshood, which will destroy them. So that Force and Punishment, by your own confession, not being able directly, by its proper Efficacy, to do Men any good, in reference to their future Estate; though it be sure directly to do them harm, in reference to their present condition [14] here; and indirectly, and in your way of applying it, being proper to do at least as much harm as good; I desire to know what the Vsefulness is which so much recommends it, even to a degree that you pretend it needful and necessary. Had you some new untry'd Chymical Preparation, that was as proper to kill as to save an infirm Man, (of whose Life I hope you would not be more tender than of a weak Brother's Soul) would you give it your Child, or try it upon your Friend, or recommend it to the World for its rare Usefulness? I deal very favourably with you, when I say as proper to kill as to save. For Force, in your indirect way, of the Magistrates applying it to make Men consider those Arguments that otherwise they would not; to make them lend an Ear to those who tell them they have mistaken their Way, and offer to shew them the right; I say in this Way, Force is much more proper, and likely, to make Men receive and imbrace Error than the Truth.

1. Because Men out of the right Way are as apt, I think I may say apter, to use Force, than others. For Truth, I mean the Truth of the Gospel, which is that of the True Religion, is mild, and gentle, and meek, and apter to use Prayers and Intreaties, than Force, to gain a hearing.

2. Because the Magistrates of the World, or the Civil Soveraigns (as you think it more proper to call them) being Pag. 16. few of them in the right Way; (not one of ten, take which side you will) perhaps you will grant not one of an hundred, being of the True Religion; 'tis likely your indirect way of using of Force would do an hundred, or at least ten times as much harm as good: Especially if you consider, that as the Magistrate will certainly use it to force Men to hearken to the proper Ministers of his Religion, let it be what it will; so you having set no Time, nor bounds, to this consideration of Arguments and Reasons, short of being convinced; you, under another pretence, put into the Magistrate's Hands as much Power to force Men to his Religion, as any the openest Persecutors can pretend to. For what difference, I beseech you, between punishing you to bring you to Mass; and punishing you to bring you to consider those Reasons and Arguments which are proper and sufficient to convince you that you ought to go to Mass? For till you are brought to consider Reasons and Arguments proper and sufficient to convince you; that is, till you are convinced; you are [15] punished on. If you reply, you meant Reasons and Arguments proper and sufficient to convince them of the Truth. I answer, if you meant so, why did you not say so? But if you had, it would in this case do you little service. For the Mass, in France, is as much supposed the Truth, as the Liturgy here. And your way of applying Force will as much promote Popery in France, as Protestantism in England. And so you see how serviceable it is to make Men receive and imbrace the Truth that must save them.

However you tell us, in the same Page, that if Force so applied, Pag. 5. as is above mentioned, may in such sort as has been said, i. e. Indirectly, and at a distance, be serviceable to bring Men to receive and imbrace Truth, you think it sufficient to shew the usefulness of it in Religion. Where I shall observe, 1st. That this Vsefulness amounts to no more but this, That it is not impossible but that it may be useful. And such a Vsefulness one cannot deny to Auricular Confession, doing of Penance, going of a Pilgrimage to some Saint, and what not. Yet our Church do's not think fit to use them: though it cannot be deny'd but they may have some of your indirect, and at a distance usefulness; that is, perhaps may do some service, indirectly, and by accident.

2. Force your way apply'd, as it may be useful, so also it may be useless. For, 1st, Where the Law punishes Dissenters, without telling them it is to make them consider, they may through ignorance and over-sight neglect to do it, and so your Force proves useless. 2. Some Dissenters may have considered already, and then Force imploy'd upon them must needs be useless; unless you can think it useful to punish a Man to make him do that which he has done already. 3. God has not directed it: and therefore we have no reason to expect he should make it successful.

3. It may be hurtful: nay it is likely to prove more hurtful than useful. 1st. Because to punish Men for that, which 'tis visible cannot be known whether they have perform'd or no, is so palpable an Injustice, that it is likelier to give them an aversion to the Persons and Religion that uses it, than to bring them to it. 2ly. Because the greatest part of Mankind being not able to discern betwixt Truth and Falshood, that depend upon long and many Proofs, and remote [16] Consequences; nor have ability enough to discover the false Grounds, and resist the captious and fallacious Arguments of Learned Men versed in Controversies; are so much more expos'd, by the Force which is used to make them hearken to the Information and Instruction of Men appointed to it by the Magistrate, or those of his Religion, to be led into Falshood and Error, than they are likely this way to be brought to imbrace the Truth that must save them; by how much the National Religions of the World are, beyond comparison, more of them False or Erroneous, than such as have God for their Author, and Truth for their Standard. And that seeking and examining, without the special Grace of God, will not secure even knowing and learned Men from Error. We have a famous instance in the two Reynold's (both Scholars, and Brothers, but one a Protestant, the other a Papist) who upon the exchange of Papers between them, were both turn'd; but so that neither of them, with all the Arguments he could use, could bring his Brother back to the Religion which he himself had found Reason to imbrace. Here was Ability to examine and judg, beyond the ordinary rate of most Men. Yet one of these Brothers was so caught by the sophistry and skill of the other, that he was brought into Error, from which he could never again be extricated. This we must unavoidably conclude; unless we can think, that wherein they differ'd, they were both in the right; or that Truth can be an Argument to support a Falshood; both which are impossible. And now, I pray, which of these two Brothers would you have punished, to make him bethink himself, and bring him back to the Truth? For 'tis certain some ill-grounded Cause of assent alienated one of them from it. If you will examine your Principles, you will find that, according to your Rule, The Papist must be punished in England, and the Protestant in Italy. So that, in effect, (by your Rule) Passion, Humour, Prejudice, Lust, Impressions of Education, Admiration of Persons, Worldly Respect, and the like incompetent Motives, must always be supposed on that side on which the Magistrate is not.

I have taken the Pains here, in a short recapitulation, to give you the view of the Vsefulness of Force, your way applied, which you make such a noise with, and lay so much stress on. Whereby I doubt not but it is visible, that its Usefulness and Uselessness laid in the Ballance against each other, the [17] pretended Vsefulness is so far from outweighing, that it can neither incourage nor excuse the using of Punishments; which are not lawful to be used in our case without strong probability of Success. But when to its Uselesness Mischief is added, and it is evident that more, much more, harm may be expected from it than good, your own Argument returns upon you. For if it be reasonable to use it, because it may be serviceable to promote true Religion, and the Salvation of Souls; it is much more reasonable to let it alone, if it may be more serviceable to the promoting Falshood, and the Perdition of Souls. And therefore you will do well hereafter not to build so much on the Vsefulness of Force, apply'd your way, your indirect and at a distance Vsefulness, which amounts but to the shadow and possibility of Vsefulness, but with an over-balancing weight of Mischief and Harm annexed to it. For upon a just estimate, this indirect, and at a distance, Vsefulness can directly go for nothing; or rather less than nothing.

But suppose Force, apply'd your way, were as useful for the promoting true Religion, as I suppose I have shew'd it to be the contrary; it does not from thence follow that it is lawful, and may be used. It may be very useful in a Parish that has no Teacher, or as bad as none, that a Lay-man who wanted not Abilities for it (for such we may suppose to be) should sometimes preach to them the Doctrine of the Gospel, and stir them up to the Duties of a good Life. And yet this, (which cannot be deny'd may be at least indirectly, and at a distance, serviceable towards the promoting true Religion and the Salvation of Souls) you will not (I imagine) allow, for this Vsefulness, to be lawful: And that, because he has not Commission and Authority to do it. The same might be said of the Administration of the Sacraments, and any other Function of the Priestly Office. This is just our Case. Granting Force, as you say, indirectly, and at a distance, useful to the Salvation of Mens Souls; yet it does not therefore follow that it is lawful for the Magistrate to use it: Because, as the Author says, the Magistrate has no Commission or Authority to do so. For however you have put it thus, (as you have fram'd the Author's Argument) Force is utterly of no use for the promoting of true Religion, and the Salvation of Souls; and therefore no body can have [18] any right to use any Force or Compulsion for the bringing Men to the true Religion; yet the Author does not, in those Pages you quote, make the latter of these Propositions an Inference barely from the former; but makes use of it as a Truth proved by several Arguments he had before brought to that purpose. For tho it be a good Argument; it is not useful, therefore not fit to be used: yet this will not be good Logick; it is useful, therefore any one has a right to use it. For if the Vsefulness makes it lawful, it makes it lawful in any hands that can so apply it; and so private Men may use it.

Who can deny, say you, but that Force indirectly, and at a distance, may do some Service towards the bringing Men to imbrace that Truth, which otherwise they would never acquaint themselves with. If this be good arguing in you, for the usefulness of Force towards the saving of Mens Souls; give me leave to argue after the same fashion. 1. I will suppose, which you will not deny me, that as there are many who take up their Religion upon wrong Grounds, to the indangering of their Souls; so there are many that abandon themselves to the heat of their Lusts, to the indangering of their Souls. 2dly, I will suppose, that as Force apply'd your way is apt to make the Inconsiderate consider, so Force apply'd another way is as apt to make the Lascivious chaste. The Argument then, in your form, will stand thus: Who can deny but that Force, indirectly, and at a distance, may, by Castration, do some Service towards bringing Men to imbrace that Chastity, which otherwise they would never acquaint themselves with. Thus, you see, Castration may, indirectly, and at a distance, be serviceable towards the Salvation of Mens Souls. But will you say, from such an usefulness as this, because it may indirectly, and at a distance, conduce to the saving of any of his Subjects Souls, that therefore the Magistrate has a right to do it, and may by Force make his Subjects Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven? It is not for the Magistrate, or any body else, upon an Imagination of its Vsefulness, to make use of any other means for the Salvation of Mens Souls than what the Author and Finisher of our Faith hath directed. You may be mistaken in what you think useful. Dives thought, and so perhaps should you and I too, if not better inform'd by the Scriptures, that it would be useful to rouze and awaken Men if one [19] should come to them from the Dead. But he was mistaken. And we are told that if Men will not hearken to Moses and the Prophets, the means appointed, neither will the Strangeness nor Terror of one coming from the Dead perswade them. If what we are apt to think useful were thence to be concluded so, we should (I fear) be obliged to believe the Miracles pretended to by the Church of Rome. For Miracles, we know, were once useful for the promoting true Religion, and the Salvation of Souls; which is more than you can say for your Political Punishments: But yet we must conclude that God thinks them not useful now; unless we will say (that which without Impiety cannot be said) that the Wise and Benign Disposer and Governour of all things does not now use all useful means for promoting his own Honour in the World, and the Good of Souls. I think this Consequence will hold, as well as what you draw in near the same words.

Let us not therefore be more wise than our Maker, in that stupendious and supernatural Work of our Salvation. The Scripture, that reveals it to us, contains all that we can know, or do, in order to it: and where that is silent, 'tis in us Presumption to direct. When you can shew any Commission in Scripture, for the use of Force, to compel Men to hear, any more than to imbrace the Doctrine of others that differ from them, we shall have reason to submit to it, and the Magistrate have some ground to set up this new way of Persecution. But till then, 'twill be fit for us to obey that Precept of the Gospel, which bids us take heed what we hear. So that hearing is not always Mark 4.24. so useful as you suppose. If it had, we should never have had so direct a Caution against it. 'Tis not any imaginary Vsefulness, you can suppose, which can make that a punishable Crime, which the Magistrate was never authorized to meddle with. Go and teach all Nations, was a Commission of our Saviour's: But there was not added to it, Punish those that will not hear and consider what you say. No, but if they will not receive you, shake off the Dust of your Feet; leave them, and apply your selves to some others. And St. Paul knew no other means to make Men hear, but the preaching of the Gospel; as will appear to any one who will read Romans the 10th, 14, &c. Faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the Word of God.

[20]

You go on, and in favour of your beloved Force, you tell Pag. 6. us that it is not only useful but needful. And here, after having at large, in the four following Pages, set out the Negligence or Aversion, or other hinderances that keep Men from examining, with that application and freedom of Judgment they should, the Grounds upon which they take up and persist in their Religion, you come to conclude Force necessary. Your words are: If Men are generally averse to a due Consideration of things, where Pag. 10. they are most concerned to use it; if they usually take up their Religion without examining it as they ought, and then grow so opinionative and so stiff in their Prejudice, that neither the gentlest Admonitions, nor the most earnest Intreaties, shall ever prevail with them afterwards to do it; what means is there left (besides the Grace of God) to reduce those of them that are got into a wrong Way, but to lay Thorns and Briars in it? That since they are deaf to all Perswasions, the uneasiness they meet with may at least put them to a stand, and incline them to lend an Ear to those who tell them they have mistaken their way, and offer to shew them the right way. What means is there left, say you, but Force. What to do? To reduce Men, who are out of it, into the right way. So you tell us here. And to that, I say, there is other means besides Force; that which was appointed and made use of from the beginning, the Preaching of the Gospel.

But, say you, to make them hear, to make them consider, to make them examine, there is no other means but Punishment; and therefore it is necessary.

I answer. 1st, What if God, for Reasons best known to himself, would not have Men compell'd to hear; but thought the good Tidings of Salvation, and the Proposals of Life and Death, Means and Inducements enough to make them hear, and consider, now as well as heretofore? Then your Means, your Punishments, are not necessary. What if God would have Men left to their freedom in this Point, if they will hear, or if they will forbear, will you constrain them? Thus we are sure he did with his own People: And this when they were in Captivity: Ezek. 11.5, 7. And 'tis very like were ill treated for being of a different Religion from the National, and so were punished as Dissenters. Yet then God expected not that those Punishments should force them to hearken, more than at other times: As appears by Ezek. 3.11. And this also is the Method of the Gospel. [21] We are Ambassadors for Christ; as if God did beseech by us, we pray in Christ's stead, says St. Paul, 2 Cor. v. 20. If God had thought it necessary to have Men punish'd to make them give Ear, he could have call'd Magistrates to be Spreaders and Ministers of the Gospel, as well as poor Fisher-men, or Paul a Persecutor, who yet wanted not Power to punish where Punishment was necessary, as is evident in Ananias and Sapphira, and the incestuous Corinthian.

2ly. What if God, foreseeing this Force would be in the hands of Men as passionate, as humoursome, as liable to Prejudice and Error as the rest of their Brethren, did not think it a proper Means to bring Men into the Right Way?

3ly. What if there be other Means? Then yours ceases to be necessary, upon the account that there is no means left. For you your self allow, That the Grace of God is another means. And I suppose you will not deny it to be both a proper and sufficient Means; and, which is more, the only Means; such Means as can work by it self, and without which all the Force in the World can do nothing. God alone can open the Ear that it may hear, and open the Heart that it may understand: and this he does in his own good Time, and to whom he is graciously pleas'd; but not according to the Will and Phancy of Man, when he thinks fit, by Punishments, to compel his Brethren. If God has pronounced against any Person or People, what he did against the Jews, (Isa. 6.10.) Make the Heart of this People fat, and make their Ears heavy, and shut their Eyes; lest they see with their Eyes, and hear with their Ears, and understand with their Hearts, and convert, and be healed: Will all the Force you can use, be a Means to make them hear and understand, and be converted?

But, Sir, to return your Argument; You see no other Means left (taking the World as we now find it) to make Men throughly and impartially examine a Religion, which they imbraced upon such Inducements as ought to have no sway at all in the Matter, and with little or no examination of the proper Grounds of it. And thence you conclude the use of Force, by the Magistrate, upon Dissenters, necessary. And, I say, I see no other Means left (taking the World as we now find it, wherein the Magistrates never lay Penalties, for Matters of Religion, [22] upon those of his own Church, nor is it to be expected they ever should;) to make Men of the National Church, any where, throughly and impartially examine a Religion, which they imbraced upon such Inducements, as ought to have no sway at all in the Matter, and therefore with little or no examination of the proper Grounds of it. And therefore, I conclude the use of Force by Dissenters upon Conformists necessary. I appeal to the World, whether this be not as just and natural a Conclusion as yours. Though, if you will have my Opinion, I think the more genuine Consequence is, that Force, to make Men examine Matters of Religion, is not necessary at all. But you may take which of these Consequences you please. Both of them, I am sure, you cannot avoid. It is not for you and me, out of an imagination that they may be useful, or are necessary, to prescribe means in the great and mysterious Work of Salvation, other than what God himself has directed. God has appointed Force as useful and necessary, and therefore it is to be used; is a way of Arguing, becoming the Ignorance and Humility of poor Creatures. But I think Force useful or necessary, and therefore it is to be used; has, methinks, a little too much presumption in it. You ask, What Means else is there left? None, say I, to be used by Man, but what God himself has directed in the Scriptures, wherein are contained all the Means and Methods of Salvation. Faith is the Gift of God. And we are not to use any other Means to procure this Gift to any one, but what God himself has prescribed. If he has there appointed that any should be forced to hear those who tell them they have mistaken their way, and offer to shew them the right; and that they should be punished by the Magistrate if they did not; 'twill be past doubt, it is to be made use of. But till that can be done, 'twill be in vain to say what other Means is there left. If all the Means God has appointed, to make Men hear and consider, be Exhortation in Season and out of Season, &c. together with Prayer for them, and the Example of Meekness and a good Life; this is all ought to be done, Whether they will hear, or whether they will forbear.

[23]

By these means the Gospel at first made it self to be heard through a great part of the World; and in a crooked and perverse Generation, led away by Lusts, Humours, and Prejudice, (as well as this you complain of) prevail'd with Men to hear and imbrace the Truth, and take care of their own Souls; without the assistance of any such Force of the Magistrate, which you now think needful. But whatever Neglect or Aversion there is in some Men, impartially and throughly to be instructed; there will upon a due Examination (I fear) be found no less a Neglect and Aversion in others, impartially and throughly to instruct them. 'Tis not the talking even general Truths in plain and clear Language; much less a Man's own Fancies in Scholastick or uncommon ways of speaking, an hour or two, once a week, in publick; that is enough to instruct even willing Hearers in the way of Salvation, and the Grounds of their Religion. They are not Politick Discourses which are the means of right Information in the Foundations of Religion. For with such, (sometimes venting Antimonarchical Principles, sometimes again preaching up nothing but absolute Monarchy and Passive Obedience, as the one or other have been in vogue and the way to Preferment) have our Churches rung in their turns, so loudly, that Reasons and Arguments proper and sufficient to convince Men of the Truth in the controverted Points of Religion, and to direct them in the right way to Salvation, were scarce any were to be heard. But how many, do you think, by Friendly and Christian Debates with them at their Houses, and by the gentle Methods of the Gospel made use of in private Conversation, might have been brought into the Church; who, by railing from the Pulpit, ill and unfriendly Treatment out of it, and other Neglects or Miscarriages of those who claimed to be their Teachers, have been driven from hearing them? Paint the Defects and Miscarriages frequent on this side, as well as you have done those on the other, and then do you, with all the World, consider whether those who you so handsomely declaim against, for being misled by Education, Passion, Humour, Prejudice, Obstinacy, &c. do deserve all the Punishment. Perhaps it will be answered; If there be so much toil in it, that particular Persons must be apply'd to, who then will be a Minister? And what if a Lay-man should [24] reply: If there be so much toil in it, that Doubts must be cleared, Prejudices removed, Foundations examined, &c. Who then will be a Protestant? The Excuse will be as good hereafter for the one as for the other.

This new Method of yours, which you say no body can deny but that indirectly, and at a distance, it does some Service towards bringing Men to embrace the Truth; was never yet thought on by the most refined Persecutors. Tho indeed it is not altogether unlike the Plea made use of to excuse the late barbarous Usage of the Protestants in France, (designed to extirpate the Reformed Religion there) from being a Persecution for Religion. The French King requires all his Subjects to come to Mass. Those who do not, are punished with a witness. For what? Not for their Religion, say the Pleaders for that Discipline, but for disobeying the King's Laws. So by your Rule, the Dissenters (for thither you would, and thither you must come, if you mean any thing) must be punished. For what? Not for their Religion, say you, not for following the Light of their own Reason, not for obeying the Dictates of their own Consciences. That you think not fit. For what then are they to be punished? To make them, say you, examine the Religion they have imbraced, and the Religion they have rejected. So that they are punished, not for having offended against a Law: For there is no Law of the Land that requires them to examine. And which now is the fairer Plea, pray judg. You ought, indeed, to have the Credit of this new Invention. All other Law-makers have constantly taken this Method; that where any thing was to be amended, the Fault was first declared, and then Penalties denounced against all those, who after a time set, should be found guilty of it. This the common Sense of Mankind, and the very Reason of Laws (which are intended not for Punishment, but Correction) has made so plain; that the subtilest and most refined Law-makers have not gone out of this course, nor have the most ignorant and barbarous Nations mist it. But you have out-done Solon and Lycurgus, Moses and our Saviour, and are resolved to be a Law-maker of a way by your self. 'Tis an old and obsolete way, and will not serve your turn, to begin with Warnings and Threats of Penalties to be inflicted on those who do not reform, but continue to [25] do that which you think they fail in. To allow of Impunity to the Innocent, or the opportunity of Amendment to those who would avoid the Penalties, are Formalities not worth your notice. You are for a shorter and surer way. Take a whole Tribe and punish them at all Adventures; whether guilty or no, of the Miscarriage which you would have amended; or without so much as telling them what it is you would have them do, but leaving them to find it out if they can. All these Absurdities are contained in your way of proceeding; and are impossible to be avoided by any one who will punish Dissenters, and only Dissenters, to make them consider and weigh the Grounds of their Religion, and impartially examine whether it be true or no, and upon what Grounds they took it up, that so they may find and imbrace the Truth that must save them. But that this new sort of Discipline may have all fair play; let us enquire,

First, Who it is you would have be punished. In the place above cited, they are those who are got into a wrong way, and Pag. 10. are deaf to all Perswasions. If these are the Men to be punished, let a Law be made against them: you have my Consent; and that is the proper course to have Offenders punished. For you do not, I hope, intend to punish any fault by a Law, which you do not name in the Law; nor make a Law against any fault you would not have punished. And now, if you are sincere, and in earnest, and are (as a fair Man should be) for what your words plainly signify, and nothing else; what will such a Law serve for? Men in the wrong Way are to be punished: but who are in the wrong Way is the Question. You have no more reason to determine it against one, who differs from you; than he has to conclude against you, who differ from him. No, not tho you have the Magistrate and the National Church on your side. For, if to differ from them be to be in the wrong Way; you, who are in the right Way in England, will be in the wrong Way in France. Every one here must be judg for himself: And your Law will reach no body, till you have convinced him he is in the wrong Way. And then there will be no need of Punishment to make him consider; unless you will affirm again, what you have deny'd, and, have Men punished for imbracing the Religion they believe to be [26] true, when it differs from yours or the Publick.

Besides being in the wrong Way, those who you would have punished must be such as are deaf to all Perswasions. But any such, I suppose, you will hardly find, who hearken to no body, not to those of their own Way. If you mean by deaf to all Perswasions, all Perswasions of a contrary Party, or of a different Church; such, I suppose, you may abundantly find in your own Church, as well as else-where; and I presume to them you are so charitable, that you would not have them punished for not lending an Ear to Seducers. For Constancy in the Truth, and Perseverance in the Faith, is (I hope) rather to be incouraged, than by any Penalties check'd in the Orthodox. And your Church, doubtless as well as all others, is Orthodox to it self, in all its Tenets. If you mean by all Perswasion, all your Perswasion, or all Perswasion of those of your Communion; you do but beg the Question, and suppose you have a right to punish those who differ from, and will not comply with you.

Your next words are, When Men fly from the means of a Pag. 11. right Information, and will not so much as consider how reasonable it is, throughly and impartially to examine a Religion, which they embraced upon such Inducements as ought to have no sway at all in the matter, and therefore with little or no Examination of the proper Grounds of it; What Human Method can be used, to bring them to act like Men, in an Affair of such Consequence, and to make a wiser and more rational Choice, but that of laying such Penalties upon them, as may ballance the weight of those Prejudices which inclin'd them to prefer a false Way before the true, and recover them to so much Sobriety and Reflection, as seriously to put the Question to themselves; Whether it be really worth the while to undergo such Inconveniencies, for adhering to a Religion, which, for any thing they know, may be false, or for rejecting another (if that be the case) which, for any thing they know, may be true, till they have brought it to the Bar of Reason, and given it a fair trial there. Here you again bring in such as prefer a false Way before a true: To which having answered already, I shall here say no more, but that, since our Church will not allow those to be in a false Way who are out of the Church of Rome, because the Church [27] of Rome (which pretends Infallibity) declares hers to be the only true Way; certainly no one of our Church (nor any other, which claims not Infallibility) can require any one to take the Testimony of any Church, as a sufficient Proof of the Truth of her own Doctrine. So that true and false (as it commonly happens, when we suppose them for our selves, or our Party) in effect, signify just nothing, or nothing to the purpose; unless we can think that true or false in England, which will not be so at Rome, or Geneva: and Vice versâ. As for the rest of the Description, of those on whom you are here laying Penalties; I beseech you consider whether it will not belong to any of your Church, let it be what it will. Consider, I say, if there be none in your Church who have imbrac'd her Religion, upon such Inducements as ought to have no sway at all in the matter, and therefore with little or no Examination of the proper Grounds of it; who have not been inclin'd by Prejudices; who do not adhere to a Religion, which for any thing they know may be false, and who have rejected another which for any thing they know may be true. If you have any such in your Communion (and 'twill be an admirable, tho I fear but a little, Flock that has none such in it) consider well what you have done. You have prepared Rods for them, for which I imagine they will con you no Thanks. For to make any tolerable Sense of what you here propose, it must be understood that you would have Men of all Religions punished, to make them consider whether it be really worth the while to undergo such Inconveniencies for adhering to a Religion which for any thing they know may be false. If you hope to avoid that, by what you have said of true and false; and pretend that the supposed preference of the true Way in your Church, ought to preserve its Members from your Punishment; you manifestly trifle. For every Church's Testimony, that it has chosen the true Way, must be taken for it self; and then none will be liable; and your new Invention of Punishment is come to nothing: Or else the differing Churches Testimonies must be taken one for another; and then they will be all out of the true Way, and your Church need Penalties as well as the rest. So that, upon your Principles, they must all or none be punished. Chuse which you please: [28] One of them, I think, you cannot escape.

What you say in the next words; Where Instruction is Pag. 11. stifly refused, and all Admonitions and Perswasions prove vain and ineffectual; differs nothing but in the way of expressing, from Deaf to all Perswasions: And so that is answer'd already.

In another place, you give us another description of those you think ought to be punished, in these words; Those who Pag. 20. refuse to embrace the Doctrine, and submit to the Spiritual Government of the proper Ministers of Religion, who by special designation, are appointed to Exhort, Admonish, Reprove, &c. Here then, those to be punished, are such who refuse to imbrace the Doctrine, and submit to the Government of the proper Ministers of Religion. Whereby we are as much still at uncertainty, as we were before, who those are who (by your Scheme, and Laws suitable to it) are to be punished. Since every Church has, as it thinks, its proper Ministers of Religion. And if you mean those that refuse to imbrace the Doctrine, and submit to the Government of the Ministers of another Church; then all Men will be guilty, and must be punished; even those of your Church, as well as others. If you mean those who refuse, &c. the Ministers of their own Church; very few will incur your Penalties. But if, by these Proper Ministers of Religion, the Ministers of some particular Church are intended; why do you not name it? Why are you so reserv'd, in a Matter wherein, if you speak not out, all the rest that you say will be to no purpose? Are Men to be punished for refusing to imbrace the Doctrine, and submit to the Government, of the proper Ministers of the Church of Geneva? For this time, (since you have declared nothing to the contrary) let me suppose you of that Church: And then, I am sure, that is it that you would name. For of what-ever Church you are, if you think the Ministers of any one Church ought to be hearken'd to, and obey'd, it must be those of your own. There are Persons to be punished, you say. This you contend for, all through your Book; and lay so much stress on it, that you make the Preservation and Propagation of Religion, and the Salvation of Souls, to depend on it: And yet you describe them by so general and equivocal Marks; that, unless it be upon Suppositions which no Body will grant you, [29] I dare say, neither you, nor any Body else, will be able to find one guilty. Pray find me, if you can, a Man whom you can, judicially prove (for he that is to be punished by Law, must be fairly tried) is in a wrong way, in respect of his Faith; I mean, who is deaf to all Perswasions, who flies from all Means of a right Information, who refuses to imbrace the Doctrine, and submit to the Government of the Spiritual Pastors. And when you have done that, I think, I may allow you what Power you please to punish him; without any prejudice to the Toleration the Author of the Letter proposes.

But why, I pray, all this bogling, all this loose talking, as if you knew not what you meant, or durst not speak it out? Would you be for punishing some Body, you know not whom? I do not think so ill of you. Let me then speak out for you. The Evidence of the Argument has convinced you that Men ought not to be persecuted for their Religion; That the Severities in use amongst Christians cannot be defended; That the Magistrate has not Authority to compel any one to his Religion. This you are forced to yield. But you would fain retain some Power in the Magistrate's Hands to punish Dissenters, upon a new Pretence; viz. not for having imbraced the Doctrine and Worship they believe to be True and Right, but for not having well consider'd their own and the Magistrate's Religion. To shew you that I do not speak wholly without-Book; give me leave to mind you of one Passage of yours. The words are, Penalties to put them upon a serious and impartial examination Pag. 26. of the Controversy between the Magistrates and them. Though these words be not intended to tell us who you would have punished, yet it may be plainly inferr'd from them. And they more clearly point out whom you aim at, than all the foregoing places, where you seem to (and should) describe them. For they are such as between whom and the Magistrate there is a Controversy: That is, in short, who differ from the Magistrate in Religion. And now indeed you have given us a Note by which these you would have punished may be known. We have, with much ado, found at last whom it is we may presume you would have punished. [30] Which in other Cases is usually not very difficult: because there the Faults to be mended easily design the Persons to be corrected. But yours is a new Method, and unlike all that ever went before it.

In the next place; Let us see for what you would have them punished. You tell us, and it will easily be granted you, that not to examine and weigh impartially, and without Prejudice or Passion, (all which, for shortness-sake, we will express by this one word Consider) the Religion one embraces or refuses, is a Fault very common, and very prejudicial to true Religion, and the Salvation of Mens Souls. But Penalties and Punishments are very necessary, say you, to remedy this Evil.

Let us see now how you apply this Remedy. Therefore, say you, let all Dissenters be punished. Why? Have no Dissenters considered of Religion? Or have all Conformists considered? That you your self will not say. Your Project therefore is just as reasonable, as if a Lethargy growing Epidemical in England; you should propose to have a Law made to blister and scarify and shave the Heads of all who wear Gowns: Though it be certain that neither all who wear Gowns are Lethargick, nor all who are Lethargick wear Gowns.

—Dii te Damasippe Deaq,

Verum ob consilium donent tonsore.

For there could not be certainly a more Learned Advice, than that one Man should be pull'd by the Ears, because another is asleep. This, when you have consider'd of it again, (for I find, according to your Principle, all Men have now and then need to be jog'd) you will, I guess, be convinced is not like a fair Physician, to apply a Remedy to a Disease; but, like an engag'd Enemy, to vent one's Spleen upon a Party. Common Sense, as well as Common Justice, requires, that the Remedies of Laws and Penalties should be directed against the Evil that is to be removed, where-ever it be found. And if the Punishment, you think so necessary, be (as you pretend) to cure the Mischief you complain [31] of, you must let it pursue and fall on the Guilty, and those only, in what company soever they are; And not, as you here propose, and is the highest Injustice, punish the Innocent considering Dissenter, with the Guilty; and, on the other side, let the inconsiderate guilty Conformist scape, with the Innocent. For one may rationally presume that the National Church has some, nay more, in proportion, of those who little consider or concern themselves about Religion, than any Congregation of Dissenters. For Conscience, or the Care of their Souls, being once laid aside; Interest, of course, leads Men into that Society, where the Protection and Countenance of the Government, and hopes of Preferment, bid fairest to all their remaining Desires. So that if careless, negligent, inconsiderate Men in Matters of Religion, who without being forced would not consider, are to be roused into a care of their Souls, and a search after Truth, by Punishments; The National Religion, in all Countries, will certainly have a right to the greatest share of those Punishments; at least, not to be wholly exempt from them.

This is that which the Author of the Letter, as I remember complains of; and that justly, viz. That the pretended Care of Mens Souls always expresses it self, in those who would have Force any way made use of to that end, in very unequal Methods; some Persons being to be treated with Severity, whilst others guilty of the same Faults are not to be so much as touched. Though you are got pretty well out of the deep Mud, and renounce Punishments directly for Religion; yet you stick still in this part of the Mire; whilst you would have Dissenters punished to make them consider, but would not have any thing done to Conformists, tho never so negligent in this point of considering. The Author's Letter pleas'd me, because it is equal to all Mankind, is direct, and will, I think, hold every where; which I take to be a good Mark of Truth. For, I shall always suspect that neither to comport with the Truth of Religion, or the Design of the Gospel, which is suited to only some one Country, or Party. What is True and Good in England, will be True and Good at Rome too, in China, or Geneva. But whether your great and only Method for [32] the propagating of Truth, by bringing the Inconsiderate by Pag. 12. Punishments to consider, would (according to your way of applying your Punishments only to Dissenters from the National Religion) be of use in those Countries, or any where but where you suppose the Magistrate to be in the Right, judg you. Pray, Sir, consider a little, whether Prejudice has not some share in your way of Arguing. For this is your Position; Men are generally negligent in examining the Grounds of their Religion. This I grant. But could there be a more wild and incoherent Consequence drawn from it, than this; Therefore Dissenters must be punished?

But that being laid aside, let us now see to what end they must be punished. Sometimes it is, To bring them to consider Pag. 5. those Reasons and Arguments which are proper and sufficient to convince them. Of what? That it is not easy to set Grantham Steeple upon Paul's Church? What-ever it be you would have them convinced of, you are not willing to tell us. And so it may be any thing. Sometimes it is, To incline them to Pag. 10. lend an Ear to those who tell them they have mistaken their Way, and offer to shew them the Right. Which is, to lend an Ear to all who differ from them in Religion; as well crafty Seducers, Pag. 27 as others. Whether this be for the procuring the Salvation Pag. 23. of their Souls, the End for which you say this Force is to be used, judg you. But this I am sure; Whoever will lend an Ear to all who will tell them they are out of the Way, will not have much time for any other Business.

Sometimes it is, To recover Men to so much Sobriety and Reflection, Pag. 11. as seriously to put the Question to themselves, Whether it be really worth their while to undergo such Inconveniences, for adhering to a Religion which, for any thing they know, may be false, or for rejecting another (if that be the case) which, for ought they know, may be true, till they have brought it to the Bar of Reason, and given it a fair Trial there. Which, in short, amounts to thus much, viz. To make them examine whether their Religion be True, and so worth the holding, under those Penalties that are annexed to it. Dissenters are indebted to you, for your great care of their Souls. But what, I beseech you, shall become of those of the National Church, every [33] where (which make far the greater part of Mankind) who have no such Punishments to make them consider; who have not this only Remedy provided for them; but are lest in that deplorable Condition, you mention, of being suffer'd quietly, Pag. 27. and without Molestation, to take no care at all of their Souls, or in doing of it to follow their own Prejudices, Humours, or some crafty Seducers: Need not those of the National Church, as well as others, bring their Religion to the Bar of Reason, and give it a fair trial there? And if they need to do so, (as they must, if all National Religions cannot be supposed true) they will always need that which, you say, is the only Pag. 12. means to make them do so. So that if you are sure, as you tell us, that there is need of your Method; I am sure, there is as much need of it in National Churches, as any other. And so, for ought I can see, you must either punish them, or let others alone; Unless you think it reasonable that the far greater part of Mankind should constantly be without that Soveraign and only Remedy, which they stand in need of equally with other People.

Sometimes the end for which Men must be punished is, to dispose Pag. 13. them to submit to Instruction, and to give a fair hearing to the Reasons are offer'd for the inlightning their Minds, and discovering the Truth to them. If their own words may be taken for it, there are as few Dissenters as Conformists, in any Country, who will not profess they have done, and do this. And if their own word; may not be taken; who, I pray must be judg? You and your Magistrates? If so, then it is plain you punish them not to dispose them to submit to Instruction, but to your Instruction; not to dispose them to give a fair hearing to Reasons offer'd for the inlightning their Minds, but to give an obedient hearing to your Reasons. If you mean this; it had been fairer and shorter to have spoken out plainly, than thus in fair words, of indefinite Signification, to say that which amounts to nothing. For what Sense is it, to punish a Man to dispose him to submit to Instruction, and give a fair hearing to Reasons offer'd for the inlightning his Mind, and discovering Truth to him, who goes two or three times a week several Miles on purpose to do it, and that with the hazard of his Liberty or Purse; Unless you mean your Instructions, your Reasons, your Truth: Which brings us [34] but back to what you have disclaimed, plain Persecution for differing in Religion.

Sometimes this is to be done, To prevail with Men to weigh Pag. 14. Matters of Religion carefully, and impartially. Discountenance and Punishment put into one Scale, with Impunity and hopes of Preferment put into the other, is as sure a way to make a Man weigh impartially, as it would be for a Prince to bribe and threaten a Judg to make him judg uprightly.