ANDREW MARVELL,

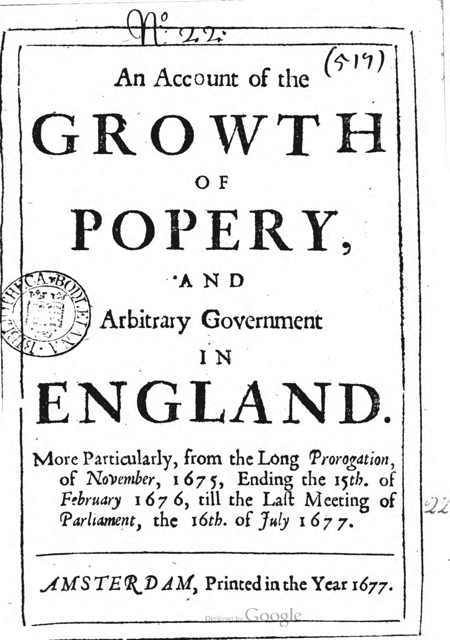

An Account of the Growth of Popery, and Arbitrary Government in England (1677)

|

[Created: 18 May, 2021]

[Updated: 30 November, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, An Account of the Growth of Popery, and Arbitrary Government in England. More Particularly, from the Long Prorogation, of November, 1675, Ending the 15th. of February 1676, till the Last Meeting of Parliament, the 16th. of July 1677. (Amsterdam, Printed in the Year 1677).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1677-Marvell_GrowthPopery/Marvell_GrowthPopery1677-ebook.html

Andrew Marvell, An Account of the Growth of Popery, and Arbitrary Government in England. More Particularly, from the Long Prorogation, of November, 1675, Ending the 15th. of February 1676, till the Last Meeting of Parliament, the 16th. of July 1677. (Amsterdam, Printed in the Year 1677).

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

[3]

An account of the Growth of POPERY, and Arbitrary Government in England, &c.

THere has now for diverse Years, a design been carried on, to change the Lawfull Government of England into an Absolute Tyranny, and to convert the established Protestant Religion into down-right Popery: than both which, nothing can be more destructive or contrary to the Interest and Happinesse, to the Constitution and Being of the King and Kingdom.

For if first we consider the State, the Kings of England Rule not upon the same terms with those of our neighbour Nations, who, having by force or by adresse usurped that due share which their People had in the Government, are now for some Ages in possession of an Arbitrary Power (which yet no Presciption can make Legall) and exercise it over their persons and estates in a most Tyrannical manner. But here the Subjects retain their proportion in the Legislature; the very meanest Commoner of England is represented in Parliament, and is a party to those Laws by which the Prince is sworn to Govern himself and his people. [4] No Mony is to be levied but by the common consent. No than is for Life, Limb, Goods, or Liberty at the Soveraigns discretion: but we have the same Right (modestly understood) in our Propriety that the Prince hath in his Regality; and in all Cases where the King is concerned, we have our just remedy as against any private person of the neighbourhood, in the Courts of Westminster Hall or in the High Court of Parliament. His very Prerogative is no more then what the Law has determined. His Broad Seal, which is the Legitimate stamp of his pleasure, yet is no longer currant, than upon the Trial it is found to be Legal. He cannot commit any person by his particular warrant. He cannot himself be witnesse in any cause: the Ballance of Publick Justice being so dellicate, that not the hand only but even the breath of the Prince would turn the scale. Nothing is left to the Kings will, but all is subjected to his Authority: by which means it follows that he can do no wrong, nor can he receive wrong; and a King of England, keeping to these measures, may without arrogance be said to remain the onely Intelligent Ruler over a Rational People. In recompense therefore and acknowledgment of so good a Government under his influence, his Person is most sacred and inviolable; and whatsoever excesses are committed against so high a trust, nothing of them is imputed to him, as being free from the necessity or temptation, but his Ministers only are accountable for all and must answer it at their perills. He hath a vast Revenue constantly arising from the Hearth of the Housholder, the Sweat of the Laboures, the Rent of the Farmer, the Industry of the Merchant, and consequently out of the Estate of the Gentleman: a larg competence to defray the ordinary expense of the Crown, and maintain its lustre. And if any extraordinary occasion happen, or be but with any probable decency pretended, the whole Land at whatsoever season of the year does yield him a plentifull Harvest. So forward are his Peoples affections to give even [5] to superfluity, that a Forainer (or English man that hath been long abroad) would think they could neither will nor chuse, but that the asking of a supply, were a meer formality, it is so readily granted. He is the Fountain of all Honours, and has moreover the distribution of so many profitable Offices of the Houshold, of the Revenue, of State, of Law, of Religion, of the Navy (and, since his persent Majesties time, of the Army) that it seems as if the Nation could scarse furnish honest men enow to supply all those imployments. So that the Kings of England are in nothing inferiour to other Princes, save in being more abridged from injuring their own subjects: But have as large a field as any of external felicity, wherein to exercise their own Virtue and so reward and incourage it in others. In short, there is nothing that comes nearer in Government to the Divine Perfection, then where the Monarch, as with us, injoys a capacity of doing all the good imaginable to mankind, under a disability to all that is evil.

And as we are thus happy in the Constitution of our State, so are we yet more blessed in that of our Church; being free from that Romish Yoak, which so great a part of Christendome do yet draw and labour under, That Popery is such a thing as cannot, but for want of a word to express it, be called a Religion: nor is it to be mentioned with that civility which is otherwise decent to be used, in speaking of the differences of humane opinion about Divine Matters. Were it either open Judaisme, or plain Turkery, or honest Paganisme, there is yet a certain Bona fides in the most extravagant Belief, and the sincerity of an erroneous Profession may render it more pardonable: but this is a compound of all the three, an extract of whatsoever is most ridiculous and impious in them, incorporated with more peculiar absurdityes of its own, in which those were deficient; and all this deliberately contrived, knowingly carried on by the bold imposture of Priests under the name of Christianity. The wisdom of this fifth Religion, this last and insolentest attempt [6] uppon the credulity of mankind seems to me (though not ignorant otherwise of the times, degrees and methods of its progresse) principally to have consisted in their owning the Scriptures to be the word of God, and the Rule of Faith and Manners, but in prohibiting of the same time their common use, or the reading of them in publick Churches but in a Latine translation to the vulgar: there being no better or more rational way to frustrate the very design of the great Institutor of Christianity, who first planted it by the extraordinary gift of Tongues, then to forbid the use even of the ordinary languages. For having thus a book which is universally avowed to be of Divine Authority, but sequestring it only into such hands as were intrusted in the cheat, they had the opportunity to vitiate, suppresse, or interpret to their own profit those Records by which the poor People hold their salvation. And this necessary point being once gained, there was thence forward nothing so monstrous to reason, so abhorring from morality, or so contrary to scripture which they might not in prudence adventure on. The Idolatry (for alas it is neither better nor worse) of adoring and praying to Saints and Angels, of worshipping Pictures, Images and Reliques, Incredible Miracles and plapable Fables to promote that veneration. The whole Liturgy and Worship of the Blessed Virgin. The saying of Pater Nosters and Creeds, to the honour of Saints, and of Ave Mary's too, not to her honour, but of others. The Publick Service, which they can spare to God among so many competitors, in an unknown tongue; and intangled with such Vestments, Consecrations, Exorcismes, Whisperings, Sprinklings, Censings, and Phantasticall Rites, Gesticulations, and Removals, so unbeseeming a Christian Office, that it represents rather the pranks and ceremonyes of Juglers and Conjurers. The Refusal of the Cup to the Laity. The necessity of the Priests Intention to make any of their Sacraments effectual. Debarring their Clergy from Marriage. Interdicting of [7] Meats. Auricular Confession and Absolution, as with them practised. Penances, Pilgrimages, Purgatory, and Prayer for the dead. But above all their other devices, that Transubstantiall solacisme, whereby that glorified Body, which at the same time they allow to be in Heaven, is sold again and crucifyed daily upon all the Altars of their Communion. For God indeed may now and then do a Miracle, but a Romish Priest can, it seems, work in one moment a thousand Impossibilityes. Thus by a new and antiscriptural Belief, compiled of Terrours to the Phansy, Contradictions to Sense, and Impositions on the Understanding, their Laity have turned Tenants for their Souls, and in consequence Tributary for their Estates to a more then omnipotent Priesthood.

I must indeed do them that right to avow that, out of an equitable consideration and recompense of so faithfull a slavery, they have discharged the People from all other services and dependance, infranchised them from all duty to God or Man; insomuch that their severer and more learned Divines, their Governors of Conscience, have so wel instructed them in all the arts of Circumventing their neighbour, and of colluding with Heaven, that, wear the scholars as apt as their teachers, their would have been long since an end of all either true Piety, or common Honesty; and nothing left among them but authorized Hypocrisy, Licentiousnesse and Knavery; had not the naturall worth of the better sort, and the Good simplicity of the meaner, in great measure preferved them. For nothing indeed but an extraordinary temper and ingenuity of spirit, and that too assisted by a diviner influence, could possibly restrain those within any the termes or Laws of humanity, who at the same time own the Doctrine of their Casuists or the Authority of the Pope, as it is by him claimed and exercised. He by his Indulgences delivers soules out of the paines of the other world: So that who would refuse to be vicious here, upon so good [8] security. He by his dispensation annuls Contracts betwixt man and man, dissoves Oaths between Princes, or betwixt them and their People, and gives allowance in cases which God and nature prohibits. He, as Clerk of the spirituall Market, hath set a rate upon all crimes: the more flagitious they are and abominable, the better Commodities, and men pay onely an higher price as for greater rarityes. So that it seemes as if the commands of God had been invented meerly to erect an Office for the Pope; the worse Christians men are, the better Customers; and this Rome does by the same policy people its Church, as the Pagan Rome did the City, by opening a sanctuary to all Malefactors. And why not, if his Power be indeed of such virtue and extent as is by him chalenged? That he is the Ruler over Angels, Purgatory and Hell. That his Tribunal and Gods are all one. That all that God, he can do, Clave non errant, and what he does is as God and not as man. That he is the Universall Head of the Church, The sole Interpreter of Scripture, and Judge of Controversy. That he is above Generall Councils. That his Power is Absolute, and his Decrees Infallible. That he can change the very nature of things, making what is Just to be Unjust, and what is Vice to be Virtue. That all Laws are in the Cabinet of his Breast. That he can Dispence with the new Testment to the great injury of the Divels. That he is still Monarch of this World, and that he can dispose of Kingdoms and Empires as he pleases. Which things being granted, that stile of Optimum, Maximum & supremum numen in terris, or that of Dominus, Deus noster, Papa, was no such extraordinary stroke of Courtship as we reckoned: but it was rather a great clownishness in him that treated so mighty a Prince under the simple Title of Vice-Deus. The exercise of his Dominion is in all points suitable to this his Pretence. He antiquates the precepts of Christ as things only of good advice, not commanded: but makes it a mortall seu even to doubt of any part of his own Religion, [9] and demands under paine of damnation the subjection of all Christians to his Papal Authority: the denying of two things so reasonable as blind obedience to this Power, and an Implicite Faith to his Doctrine, being the most unpardonable crime, under his Dispensation. He has indeed of late been somewhat more retentive then formerly as to his faculty of disposing of Kingdomes, the thing not having succeeded well with him in some instances: but he layes the same claim still, continues the same inclination, and though velvet headed hath the more itch to be pushing. And however in order to any occasion he keeps himself in breath always by cursing one Prince or other upon every Maunday Thusday: Nor is their any, whether Prince or Nation, that dissents from his Usurpations, but are marked out under the notion of Hereticks to ruine and destruction whensover he shall give the signal. That word of Heresy misapplyed, hath served him for so many Ages to Justify all the Executions, Assassinations, Warrs, Massacres, and Devastations, whereby his Faith hath been Propagated; of which our times also have not wanted examples, and more is to be expected for the future. For by how much any thing is more false and unreasonble, it requires more cruelty to establish it: and to introduce that which is absurd, there must be somwhat done that is barbarous. But nothing of any sect in Religion can be more recommended by all these qualityes then the Papacy. The Pagans are excusable by their natural darkness, without Revelation. The Jews are tolerable, who see not beyond the Old Testament. Mahomet was so honest as to own what he would be at, that he himself was the greatest Prophet, and that his was a Religion of the Sword. So that these were all, as I may say, of another Allegiance and if Enemys, yet not Traytors: But the Pope avowing Christianity by profession doth in Doctrine and practise renonce it: and presuming to be the only Catholick, does persecute those to [10] the death who dare worship the Author of their Religion instead of his pretended Vicegerent.

And yet there is nothing more evident, notwithstanding his most notorious forgeries and falsification of all Writers, then that the Pope was for severall Hundred of Years an honest Bishop as other men are, and never so much as dreamed upon the Seven Hills of that universal power which he is now come to: nay was the first that opposed any such pretension. But some of them at last, growing wiser, by foisting a counterfeit Donation of Constantine, and wresting another Donation from our Saviour, advanced themselves in a weak, ignorant, and credulous Age, to that Temporal and Spiritual Principality that they are now seised of. Tues Petrus, & super hanc Petram, adificabo Ecclesiam meam. Never was a Bishop-prick and a Verse of Scripture so improved by good management. Thus, by exercising in the quality of Christs Uicar the publick function under an invisible Prince, the Pope, like the Maires of the Palace, hath set his master aside and delivered the Government over to a new Line of Papal Succession. But who can, unlesse wilfully, be ignorant what wretched doings, what Bribery, what Ambition there are, how long the Church is without an Head upon every Vacancy, till among the crew of bandying Cardinalls the Holy Ghost have declared for a Pope of the French or Spanish Faction. It is a sucession like that of the Egyptian Ox (the living Idol of that Country) who dying or being made away by the Priests, there was a solemn and general mourning for want of a Deity; until in their Conclave they had found out another Beast with the very same marks as the former, whom then they themselvs adored and with great Jubilee brought forth to the People to worship. Nor was that Election a grosser reproach to human Reason then this is also to Christianity. Surely it is the greatest Miracle of the Romish Church that it should still continue, and that in all this time the Gates of Heaven should not prevaile against it.

[11]

It is almost unconceivable how Princes can yet suffer a Power so pernicious, and Doctrine so destructive to all Government. That so great a part of the Land should be alienated and condemned to, as they call it, Pious Uses. That such millions of their People as the Clergy, should, by remaining unmarryed, either frustrate humane nature if they live chastly, or, if otherwise, adulterate it. That they should be priviledged from all labour, all publick service, and exempt from the power of all Secular Jurisdiction. That they, being all bound, by strict Oaths and Vows of Obedience to the Pope, should evacuate the Fealty due to the Soveraign. Nay, that not only the Clergy but their whole People, if of the Romish preswasion, should be obliged to rebel at any time upon the Popes pleasure. And yet how many of the Neighbouring Princes are content, or do chuse to reign, upon those conditions; which being so dishonorable and dangerous, surely some great and more weighty reason does cause them submit to. Whether it be out of personal fear, having heard perhaps of several attempts which the blind obedience of Popish Zelotes hath executed against their Princes. Or, whether aiming at a more absolute and tyrannical Government, they think it still to be the case of Boniface and Phocas (an usurping Emperour and an usurping Bishop) and that, as other Cheats, this also is best to be managed by Confederacy. But, as farre as I can apprehend, there is more of Sloth then Policy on the Princes side in this whole matter: and all that pretense of inslaving men by the assistance of Religion more easily, is neither more nor lesse then when the Bramine, by having the first night of the Bride assures himself of her devotion for the future, and makes her more fit for the husband.

This reflection upon the state of our Neighbours, in aspect to Religion, doth sufficiently illustrate our happinesse, and spare me the labour of describing it further, then by the Rule of Contraryes: Our Church standing upon all points [12] in a direct opposition to all the forementioned errours. Our Doctrine being true to the Principles of the first Christian institution, and Episcopacy being formed upon the Primitive Model, and no Ecclesiastical Power jostling the Civil, but all concurring in common obedience to the Soveraign. Nor therefore is their any, whether Prince or Nation, that can with less probability be reduced back to the Romish perswasion, than ours of England.

For, if first we respect our Obedience to God, what appearance is there that, after so durable and general an enlightning of our minds with the sacred Truth, we should again put out our own Eyes, to wander thorow the palpable darkness of that gross Superstition? But forasmuch as most men are less concern'd for their Interest in Heaven than on Earth, this seeming the nearer and more certain, on this account also our alteration from the Protestant Religion is the more impossible. When beside the common ill examples and consequences of Popery observable abroad, whereby. we might grow wise at the expense of our Neighbours, we cannot but reflect upon our own Experiments at home, which would make even fools docible. The whole Reign of Queen Mary, in which the Papists made Fewel of the Protestants. The Excommunicating and Deprivation of Queen Elizabeth by the Pope, pursued with so many Treasons and attempts upon her Person, by her own Subjects, and the Invasion in Eighty-Eight by the Spanish. The two Breves of the Pope, in order to exclude King James from the Succession to the Crown, seconded by the Gunpowder-Treason. In the time of his late Majesty, King Charles the first, (besides what they contributed to the Civil War in England) the Rebellion and horrid Massacre in Ireland, and, which was even worse than that, their pretending that it was done by the Kings Commission, and vouching the Broad Seal for their Authority. The Popes Nuncio assuming nevertheless and exercising there the Temporal as well as Spiritual Power, [13] granting out Commissions under his own Hand, breaking the Treatys of Peace between the King, and, as they then styled themselves, the Confederate Catholicks; heading two Armies against the Marquess of Ormond, then Lord Lieutenant, and forcing him at last to quit the Kingdom: all which ended in the Ruine of his Majesties Reputation, Government, and Person; which but upon occasion of that Rebellion, could never have happened. So that we may reckon the Reigns of our late Princes, by a succession of the Popish Treasons against them. And, if under his present Majesty we have as yet seen no more visible effects of the same spirit than the Firing of London (acted by Hubert, hired by Pieddelou two French-men) which remains a Controverfie, it is not to be attributed to the good nature or better Principles of that Sect, but to the wisdom of his Holyness; who observes that we are not of late so dangerous Protestants as to deserve any special mark of his Indignation, but that we may be made better use of to the weakning of those that are of our own Religion, and that if he do not disturbe us, there are those among our selves, that are leading us into a fair way of Reconciliation with him.

But those continued fresh Instances, in relation to the Crown, together with the Popes claim of the Temporal and immediate Dominion of the Kingdoms of England and Ireland, which he does so challenge, are a sufficient caution to the Kings of England, and of the People, there is as little hopes to seduce them, the Protestant Religion being so interwoven as it is with their Secular Interest. For the Lands that were formerly given to superstitious uses, having first been applyed to the Publick Revenue, and afterwards by severall Alienations and Contracts distributed into private possession, the alteration of Religion would necessarily introduce a change of Property. Nullum tempus occurrit Ecelesiae, it would make a general Earth-quake over the nation, and even now the Romish Clergy on the other side of the [14] water, snuffe up the savoury odour of so many rich Abbies and Monasteries that belonged to their predecessors. Hereby no considerably Estate in England but must have a piece torn out of it upon the Titile of Piety, and the rest subject to be wholly forfeited upon the account of Heresy. Another Chimny mony of the old Peter pence must again be payed. as tribute to the Pope, beside that which is established on his Majesty: and the People, instead of those moderate Tithes that are with too much difficulty payed to their Protestant Pastors, will be exposed to all the exactions, of the Court of Rome, and a thousand artifices by which in former times they were used to draine away the wealth of ours more then any other Nation. So that in conclusion, there is no English-man that hath a Soul, a Body, or an Estate to save, that Loves either God, his King, or his Country, but is by all those Tenures bound, to the best of his Power and Knowledge, to maintaine the established Protestant Religion.

And yet, all this notwithstanding, there are those men among us, who have undertaken, and do make it their businesse, under so Legal and perfect a Government, to introduce a French slavery, and instead of so pure a Religion, to establish the Roman Idolatry: both and either of which are Crimes of the Highest nature. For, as to matter of Government, if to murther the King be, as certainly it is, a Fact so, horred, how much more hainous is it to assassinate the Kingdome? And as none will deny, that to alter our Monarchy into a Commonwealth were Treason, so by the same Fundamenttal Rule, the Crime is no lesse to make that Monarchy Absolute.

What is thus true in regard of the State, holds as well in reference to our Religion. Former Parliaments have made it Treason in whosoever shall attempt to seduce any one, the meanest of the Kings subjects, to the Church of Rome: And this Parliament hath, to all penalties by the Common or Statute Law, added incapacity for any man who shall presume [15] to say that the King is a Papist or an Introducer of Popery. But what lawless and incapable miscreants then, what wicked Traytors are those wretched men, who endevour to pervert our whole Church, and to bring that about in effect, which even to mention is penal, at one Italian stroke attempting to subvert the Government and Religion, to kill the Body and damn the Soul of our Nation.

Yet were these men honest old Cavaliers that had suffered in his late Majesties service, it were allowable in them, as oft as their wounds brake out at Spring or Fall, to think of a more Arbitrary Government, as a soveraign Balsom for their Aches, or to imagine that no Weapon-salve but of the Moss that grows on an Enemies Skul could cure them. Should they mistake this Long Parliament also for Rebells, and that, although all Circumstances be altered, there were still the same necessity to fight it all over again in pure Loyalty, yet their Age and the Times they have lived in, might excuse them. But those worthy Gentlemen are too Generous, too good Christians and Subjects, too affectionate to the good English Government, to be capable of such an Impression. Whereas these Conspiratours are such as have not one drop of Cavalier Blood, or no Bowels at least of a Cavalier in them; but have starved them, to Revel and Surfet upon their Calamities, making their Persons, and the very Cause, by pretending to it themselves, almost Ridiculous.

Or, were these Conspiratours on the other side but avowed Papists, they were the more honest, the less dangerous, and the Religion were answerable for the Errours they might commit in order to promote it. Who is there but must acknowledge, if he do not commend the Ingenuity (or by what better Name I may call it) of Sir Thomas Strickland, Lord Bellassis, the late Lord Clifford and others, eminent in their several stations? These, having so long appeared the most zealous Sons of our Church, yet, as soon as the late [16] Test against Popery was inacted, tooke up the Crosse, quitted their present imployments and all hopes of the future, rather then falsify their opinion: though otherwise men for Quality, Estate and Abilityes whether in Warre or Peace, as capable and well deserving (without disparagement) as others that have the art to continue in Offices. And above all his Royal Highnesse is to be admired for his unparallelled magnanimity on the same account: there being in all history perhaps no Record of any Prince that ever changed his Religion in his circumstances. But these persons, that have since taken the worke in hand, are such as ly under no temptation of Religion: secure men, that are above either Honour or Consciencs; but obliged by all the most sacred tyes of Malice and Ambition to advance the ruine of the King and Kingdome, and qualified much better then others, under the name of good Protestants, to effect it.

And because it was yet difficult to find Complices enough at home, that were ripe for so black a desing, but they wanted a Back for their Edge; therefore they applyed themselves to France, that King being indowed with all those qualityes, which in a Prince, may passe for Virtues; but in any private man, would be capital; and moreover so abounding in wealth that no man else could go to the price of their wickednesse: To which Considerations, adding that he is the Master of Absolute Dominion, the Presumptive Monarch of Christendom, the declared Champion of Popery, and the hereditary, natural, inveterate Enemy of our King and Nation, he was in all respects the most likely (of all Earthly Powers) to reward and support them in a Project every way suitable to his one Inclination and Interest.

And now, should I enter into a particular retaile of all former and latter Transactions, relating to this affaire, there would be sufficient for a just Volume of History. But my intention is onely to write a naked Narrative of some the most considerable passages in the meeting of Parliament [17] the 15 of Febr. 1676. Such as have come to my notice which may serve for matter to some stronger Pen and to such as have more leisure and further opportunity to discover and communicate to the Publick. This in the mean time will by the Progresse made in so few weeks, demonstrate at what rate these men drive over the necks of King and People, of Religion and Government; and how near they are in all humane probability to arrive Triumphant at the end of their Journey. Yet, that I may not be too abrupt, and leave the Reader wholly destitute of a thread to guide himself by thorow so intriguing a Labyrinth, I shall summarily as short, as so copious and redundant a matter will admit, deduce the order of affaires both at home and abroad, as it led into this Session.

It is well known, were it as well remembred, what the provocation was, and what the successe of the warre begun by the English in the Year 1665. against Holland: what vast supplyes were furnished by the Subject for defraying it, and yet after all. no Fleet set out, but the Flower of all the Royal Navy burnt or taken in Port to save charges. How the French, during that War, joyned themselves in assistance of Holland against us, and yet, by the credit he had with the Queen Mother, so farre deluded his Majesty, that upon assurance the Dutch neither would have any Fleet out that year, he forbore to make ready, and so incurred that notable losse, and disgrace at Chatham. How (after this fatall conclusion of all our Sea-Champaynes) as we had been obliged to the French for that warre, so we were glad to receive the Peace from his favour which was agreed at Breda betwixt England, France, and Holland.

His Majesty was hereby now at leisure to remarke how the French had in the year 1667. taken the time of us and while we were imbroled and weakned had in violation of all the most solemn and sacred Oaths and Treatyes invaded and taken a great part of the Spanish Nether-Land, which had [18] alwayes been considered as the natural Frontier of England. And hereupon he judged it necessary to interpose, before the flame that consumed his next neighbour should throw its sparkles over the water. And therefore, generously slighting all punctilious of ceremony or peeks of animosity, where the safty of his People and the repose of Christendom were concerned, he sent first into Holland, inviting them to a nearer Alliance, and to enter into such further Counsells as were most proper to quiet this publick disturbance which the French had raised. This was a work wholy of his Majestys designing and (according to that felicity which hath allways attended him, when excluding the corrupt Politicks of others he hath followed the dictates of his own Royal wisdom) so well it succeeded. It is a thing searse credible, though true, that two Treatyes of such weight, intricacy, and so various aspect as that of the Defensive League with Holland, and the other for repressing the further progresse of the French in the Spanish Netherland, should in five days time, in the year 1668. be concluded. Such was the Expedition and secrecy then used in prosecuting his Majesty particuler instructions, and so easy a thing is it for Princes, when they have a mind to it, to be well served. The Swede too shortly after made the third in this Concert; whether wisely judging that in the minority of their King reigning over several late acquired dominions, it was their true intrest to have an hand in all the Counsells that tended to pease and undisturbed possession, or, whether indeed those ministers, like ours, did even then project in so glorious an Alliance to betray it afterward to their own greater advantage. From their joyning in it was called the Triple Alliance, His Majesty with great sincerity continued to solicite other Princes according to the seventh Article to come into the Guaranty of this Treaty, and delighted himself in cultivating by all good means what he had planted. But in a very short time these Counsells, which had taken effect with so great satisfaction to the Nation and [19] to his Majestyes eternal honour, were all changed and it seemed that Treatyes, as soon as the Wax is cold, do lose their virtue. The King in June 1670 went down to Dover to meet after a long absence. Madam, his onely remaining sister: where the days were the more pleasant, by how much it seldomer happens to Princes then private persons to injoy their Relations, and when they do, yet their kind interviews are usually solemnized with some fatlity and disaster, nothing of which here appeared. But upon her first return into France she was dead, the Marquess of Belfonds was immediately sent hither, a Person, of great Honour dispatched thither? and, before ever the inquiry and grumbling at her death could be abated, in a trice there was an invisible Leagle, in prejudice of the Triple one, struck up with France, to all the height of dearnesse and affection. As if upon discecting the Princess there had some state Philtre been found in her bowells, or the reconciliation wiah France were not to be celebrated with a lesse sacrifice then of the Blood Royall of England. The sequel will be suitable to so ominous a beginning. But, as this Treaty was a work of Darknesse and which could never yet be understood or discovered but by the effects, so before those appeared it was necessary that the Parliament should after the old wont be gulld to the giving of mony. They met the 24th Oct. 1670. and it is not without much labour that I have been able to recover a written Copy of the Lord Bridgmans speech, none being printed, but forbidden, doubtlesse lest so notorious a Practise as certainly was never before, though there have indeed been many, put upon the Nation, might remain publick. Although that Honourable person cannot be persumed to have been accessory to what was then intended, but was in due time, when the Project ripened and grew hopeful, discharged from his Office, and he, the Duke of Ormond, the late Secretary Trevor, with the Prince Rupert, discarded together out of the Committee for the Forraign Affaires, He spoke thus.

[20]

My Lords, and you the Knights, Citizens and Burgesses of the House of Commons.

WHen the two Houses were last Adjourned, this Day, as you well know, was perfixed for your Meeting again. The Proclamation since issued requiring all your attendances at the same time shewed not only his Majesties belief that his business will thrive best when the Houses are fullest, but the importance also of the Affaires for which you are so called: And important they are. You cannot be ignorant of the great Forces both for Land and Sea-service which our Neighbours of France and the Low-Countries have raised, and have now in actual Pay; nor of the great Preparations which they continue to make in Levying of Men, Building of Ships, filling their Magazines and Stores with immense quantities of all sorts of Warlike Provisions. Since the beginning of the last Dutch War, the French have increased the Greatness and Number of their Ships so much, that their Strength by Sea is thrice as much as it was before. And since the end of it, the Dutch have been very diligent also in augmenting their Fleets. In this conjuncture, when our Neighbours Arm so potently, even common prudence requires that his Majesty should make some suitable [21] preparations; that he may at least keep pace with his Neighbours, if not out-go them in Number and Strength of Shipping. For this being an Island, both our Safety, our Trade, our Being, and our Well-Being depend upon our Forces at Sea.

His Majesty therefore, of his Princely Care for the Good of his People, hath given order for the fitting out of Fifty Sayl of his Greatest Ships, against the Spring, besides those which are to be for Security of our Merchants in the Mediterranean: As foreseeing, if he should not have a considerable Fleet, whilst his Neighbours have such Forces both at Land and Sea, Temptation might be given to those who seem not now to intend it, to give us an Affront, at least, if not to do us a Mifchief.

To which may be added, That his Majesty, by the Leagues which he hath made, for the Common Peace of Christendom, and the good of his Kingdoms, is obliged to a certain Number of Forces in case of Infraction thereof, as also for the Assistance of some of his Neighbours, in case of Invasion. And his Majesty would be in a very ill condition to perform his part of the Leagues (if whilst the Clouds are gathering so thick about us) he should, in hopes that the Wind will disperse them, omit to provide against the Storm.

My Lords and Gentlemen, Having named the [22] Leagues made by his Majesty, I think it necessary to put you in mind, That since the Close of the late War, his Majesty hath made several Leagues, to his own great Honour, and infinite Advantage to the Nation.

One known by the Name of the Tripple Alliance, wherein his Majesty, the Crown of Sweden and the States of the United Provinces are ingaged to preserve the Treaty of Aix la Capelle, concerning a Peace between the two warring Princes, which Peace produced that effect, that it quenched the Fire which was ready to have set all Christendom in a Flame. And besides other great Benefits by it, which she still enjoyes, gave opportunity to transmit those Forces against the Infidels, which would otherwise have been imbrued in Christian Blood.

Another between his Majesty and the said States for a Mutual Assistance with a certain number of Men and Ships in case of Invasion by any others.

Another between his Maiesty and the Duke of Savoy, Establishing a Free Trade for his Majesties Subjects at Villa Franca, a Port of his own upon the Mediterranean, and through the Dominions of that Prince; and thereby opening a Passage to a Rich part of Italy, and part of Germany, which will be [23] of a very great advantage for the Vending of Cloth and other our home Commodities, bringing back Silk and other Materials for Manifactures than here.

Another between his Majesty and the King of Denmark, whereby those other Impositions that were lately laid upon our Trade there, are taken off, and as great Priviledges granted to our Merchants, as ever they had in former Times, or as the Subjects of any other Prince or State do now enjoy.

And another League upon a Treaty of Commerce with Spain, whereby there is not only a Cessation and giving up to his Majesty of all their Pretensions to Jamaica, and other Islands and Countries in the West Indies, in the Possession of his Majesty or his Subjects, but with all, free Liberty is given to his Majesties Subjects, to enter their Ports for Victuals and Water, and safety of Harbour and Return, if Storm or other Accidents bring them thither; Priviledges which were never before granted by them to the English or any Others.

Not to mention the Leagues formerly made with Sweden and Portugal, and the Advantages which we enjoy thereby; nor those Treaties now depending between his Majesty and France, or his Majesty and the States of tbe United Provinces touching Commerce, wherein his Majesty will have a singular regard [24] to the Honour of this Nation, and also to the Trade of it, which never was greater than now it is.

In a word, Almost all the Princes in Europe do seek his Majesties Friendship, as acknowledging they cannot Secure, much less Improve their present condition without it.

His Majesty is confident that you will not be contented to see him deprived of all the advantages which he might procure hereby to his own Kingdoms, nay even to all Christendom, in the Repose and Quiet of it. That you will not be content abroad to see your Neighbours strengthening themselves in Shipping, so much more than they were before, and at Home to see the Government strugling every year with Difficulties; and not able to keep up our Navies equal with theirs. He findes that by his Accounts from the year 1660 to the Late War, the ordinary Charge of the Fleet Communibus annis, came to about 500000 l. a year, and it cannot be supported with less.

If that particular alone take up so much, add to it the other constant Charges of the Government, and the Revenue (although the Commissioners of the Treasury have mannag'd it with all imaginable Thrift) will in no degree suffice to take of the Debts due upon Interest, much less give him a Fonds for the fitting out of this Fleet, which by common Estimation thereof [25] cannot cost less than 800000 l. His Majesty in his most gracious Speech, hath expressed the great sence he hath of your zeal and affection for him, and as he will ever retain a grateful memory of your former readiness to supply him in all Exigencies, so he doth with particular thanks acknowledge your frank and chearfull Gift of the New Duty upon Wines, at your last Meeting: But the same is likely to fall very short in value of what it was conceived to be worth, and should it have answered expectation, yet far too short to ease and help him upon these Occasions. And therefore such a Supply as may enable him to take off his Debts upon Interest, and to set out this Fleet against the Spring, is that which he desires from you, and recommends it to you, as that which concerns the Honour and Support of the Government, and the Wellfare and Safety of your Selves and the whole Kingdome.

My Lords and Gentlemen, You may perceive by what his Majesty hath already said, that he holds it requisite that an End be put to this Meeting before Christmas. It is so not only in reference to the Preparation for his Fleet, which must be in readiness in the Spring, but also to the Season of the Year. It is a time when you would be willing to be in your Countries, and your Neighbours would be glad to see you there, and partake of your Hospitality and Charity, and you [26] thereby endear your selves to them, and keep up that Interest and Power among them, which is necessary for the service of your King and Country, and a Recesse at that time, leaving your business unfinished till your Return, cannot either be convenient for you, or suitable to the condition of his Majesties Affaires, which requires your Speedy, as well as Affectionate Consideration.

[27]

There needed not so larg a Catalogue of pass, present and future Leagues and Treaties, for even Villa Franca sounded so well (being besides so considerable a Port, and that too upon the Mediterranean (another remote word of much efficacie) and opeing moreover a passage to a rich part of Italy, and a part of Germany, &c.) that it alone would have sufficed to charm the more ready Votes of the Commons into a supply, and to justifie the Necessity of it in the noise of the Country. But indeed the making of that Tripple League, was a thing of so good a report and so generally acceptable to the Nation, as being a hook in the French nostrils, that this Parliament (who are used, whether it be War or Peace, to make us pay for it) could not have desired a fairer pretence to colour their liberality.

And therefore after all the immense summs lavished in the former War with Holland, they had but in April last, 1670, given the Additional Duty upon Wines for 8 years; amounting to 560000 and confirmed the sale of the Fee Farm Rents, which was no lesse their gift, being a part of the publick Revenue, to the value of 180000l. Yet upon the telling of this Storie by the Lord Keeper, they could no longer hold but gave with both hands now again a Subsidy of 1s. in the pound to the real value of all Lands, and other Estates proportionably, with several more beneficial Clauses into the bargaine, to begin the 24 of June 1671, and expire the 24 of June 1672. Together with this, they granted the Additional Excise upon Beer, Ale, &c. for six years, to reckon from the same 24th of June 1671. And lastly, the Law Bill commencing from the first of May 1671, and at nine yeares end to determine. These three Bills summed up therefore cannot be estimated at lesse than two millions and an half.

So that for the Tripple League, here was, also Tripple-Supply, and the Subject had now all reason to beleive that this Alliance, which had been fixed at first by the Publick Interest, Safety and Honour (yet, should any of those give way) was [28] by these Three Grants, as with three Golden Nailes, sufficiently clenched and reivetted. But now therefore was the most proper time and occasion for the Conspirators, I have before described, to give demonstration of their fidelitie to the French King and by the forfeiture of all these obligations to their King and Countrey, and other Princes, and at the expense of all this Treasure given to contrarie uses, to recommend themselves more meritoriously to his patronage.

The Parliament having once given this Mony, were in consequence Prorogued, and met not again till the 4th of February 1672, that there might be a competent scope for so great a work as was desined, and the Architects of our Ruine might be so long free from their busie and odious inspection till it were finished. Henceforward, all the former applications made by his Majesty to induce Forraine Princes into the Guaranty of the Treaty of Aix la Chapelle ceased, and on the contrary, those who desired to be admitted into it, were here refused. The Duke of Loraine, who had alwaies been a true Freind to his Majesty, and by his affection to the Tripple League had incurred the French Kings displeasure, with the losse of his whole Territorie, seised in the year 1669, against all Laws not only of Peace but Hostility, yet was by means of these men rejected, that he might have no Intrest in the Alliance, for which he was sacrificed. Nay even the Emperour, though he did his Majesty the Honour to address voluntarily to him, that himself might be received into that Tripple League, yet could not so great a Prince prevail but was turned off with blind Reason, and most srivolous Excuses. So farre was it now from fortifying the Alliance by the Accession of other Princes, that Mr. Henry Goventry went now to Sweden expresly, as he affirmed at his departure hence, to dissolve the Tripple League. And he did so much towards it, cooperating in that Court with the French Ministers, that Sweden never (after it came to a Rupture) did assist or prosecute effectually the ends of the [29] Alliance, but only arming it self at the expence of the Leagues did first, under a disguised Mediation, Act the French Interest, and at last threw off the Vizard, and drew the Sword in their Quarrel. Which is a matter of sad reflexion, that he, who in his Embassy at Breda, had been so happy an Instrument to end the first unfortunate War with Holland, should now be made the Toole of a second, and of breaking that threefold Cord, by which the Interest of England and all Christendom was fastned. And, what renders it more wretched, is, that no man better than He understood both the Theory and Practick of Honour; and yet, cold in so eminent an Instance, forget it. All which can be said in his excuse, is, that upon his return he was for this service made Secretary of State (as if to have remained the same Honest Gentleman, had not been more necessary and lesse dishonourable) Sir William Lockyard and several others were dispatched to other Courts upon the like errand.

All things were thus farre well disposed here toward a War with Holland: only all this while there wanted a Quarrel, and to pick one required much invention. For the Ducth although there was a si quis to find out complaints, and our East India Company was summoned to know whether they had any thing to object against them, had so punctually complyed with all the Conditions of the Peace at Breda, and observed his Majesty with such respect (and in paying the due Honour of the Flagg particulary as it was agreed in the 19th. Article) that nothing could be alleadged: and as to the Tripple League, their Fleet was then out, riding near their own Coasts, in prosecuting of the ends of that Treaty. Therefore, to try a new experiment and to make a Case which had never before happened or been imagined, a sorry Yatch, but bearing the English Jack, in August 1671. Sailes into the midst of their Fleet, singled out the Admyral, shooting twice, as they call it, sharpe upon him. Which must sure have appeared as ridiculous, and unnatural as for a Larke to dare the Hobby. [30] Neverthelesse their Commander in Chief, in diference to his Majestys Colours, and in consideration of the Amity betwixt the two Nations, payed our Admiral of the Yatch a visit, to know the reason; and learning that it was because he and his whole Fleet had failed to strike Saile to his small-craft, the Dutch Commander civilly excused it as a matter of the first instance, and in which he could have no Instructions, therefore proper to be referred to their Masters, and so they parted. The Yatch having thus acquitted it self, returned, fraught with the Quarrel she was sent for, which yet was for several months passed over here in silence without any Complaint or demand of satisfaction, but to be improved afterwards when occasion grew riper. Forthere was yet one thing more to be done at home to make us more capable of what was shortly after to be executed on our Neighbours.

The Exohequer had now for some years by excessive gain decoy'd in the wealthy Goldsmiths, and they the rest of the Nation by due payment of Interest, till the King was run (upon what account I know not) into debt of above two Millions: which served for one of the pretences in my Lord Keepers Speech above recited, to demand and grant the late Supplies, and might have sufficed for that work, with peace and any tolerable good husbandry. But as if it had been perfidious to apply them to any one of the Purposes declared) it was instead of payment privately resolved to shut up the Exchequer, least any part of the money should be legally expended, but that all might be appropriate to the Holy War in project, and those further pious uses to which the Conspirators had dedicated it.

This affair was carried on with all the secresy of so great Statesmen, that they might not by venting it unseasonably spoile the wit and malice of the business. So that all on the suddain, upon the first of January 1671, to the great astonishment, ruine and despaire of so many interested persons, and to the terrour of the whole Nation, by so Arbitrary a [31] Fact, the Proclamation issued whereby the Crown, amid'st the confluence of so vast Aides and Revenue, published it self Bankrupt, made prize of the Subject, and broke all Faith and contract at home in order to the breaking of them abroad with more advantage.

There remained nothing now but that the Conspirators, after this exploit upon our own Countrymen, should manifest their impartiallity to Forainers, and avoid on both sides the reproach of Injustice by their equality in the distribution. They had now started the dispute about the Flag upon occasion of the Yatch, and begun the discourse of Surinam, and somwhat of Pictures and Medalls, but they handled these matters so nicely as men not lesse afraid of receiving all satisfaction therein from the Hollanders, then of giving them any umbrage of arming against them upon those pretenses. The Dutch therefore, not being conscious to themselves of any provocation given to England, but of their readinesse, if there had been any, to repair it, and relying upon that faith of Treatyes and Alliances with us, which hath been thought sufficient security, not only amongst Christians but even with Infidels, pursued their Traffick and Navigation thorow our Seas without the least suspicion. And accordingly a great and rich Fleet of Merchantmen from Smyrna and Spain, were on their Voyage homeward near the Isle of Wight, under a small Convoy of five or six of their Men of War. This was the Fleet in contemplation of which the (conspirators had so long deferred the War to plunder them in peace; the wealth of this was that which by its weight turned the Ballance of all Publick Justice and Honour; with this Treasure they imagined themselves in stock for all the wickednesse of which they were capable, and that they should never, after this addition, stand in need again or fear of a Parliament. Therefore they had with great stilnesse and expidition equipped early in the year, so many of the Kings Ships as might without jealousy of the number, yet be of competent [32] strength for the intended action, but if any thing should chance to be wanting, they thought it abundantly supplyed by virtue of the Commander. For Sir Robert Holmes had with the like number of Ships in the year 1661, even so timely, commenced the first Hostility against Holand, in time of Peace; seizing upon Cape Verde, and other of the Dutch-Forts on the Coast of Guiny, and the whole New Nether-lands, with great success: in defence of which Conquests, the English undertook, 1665, the first War against Holand. And in that same War, he with a proportionable Squadron signalized himself by burning the Dutch Ships and Village of Brandaris at Schelling, which was unfortunately revenged upon us at Chatham. So that he was pitched upon as the person for understanding, experience and courage, fittest for a design of this or any higher nature; and upon the 14th. of March, 1672. as they sailed on, to the number of 72 Vessells in all, whereof six the Convoy; near our Coast, he fell in upon them with his accustomed bravery, and could not have failed of giving a good account of them, would he but have joyned fortunes, Sr. Edward Spraggs Asistance to his own Conduct: For Sr. Edward was in sight at the same time with his Squadron, and Captaine Legg making saile towards him, to acquaint him with the design, till called back by a Gun from his Admirall, of which severall persons have had their conjectures. Possibly Sr. Robert Holmes, considering that Sr. Edward had sailed all along in consort with the Ducth in their voyage, and did but now return from bringing the Pirates of Algier to reason, thought him not so proper to ingage in this enterprise before he understood it better. But it is rather beleived to have proceeded partly from that Jealousy (which is usuall to marshal spirits, like Sr. Roberts) of admitting a Companion to share with him in the Spoile of Honour or Profit; and partly out of too strict a regard to preserve the secret of his Commission. However, by this meanes the whole affair miscarried. For the Merchant [33] Men themselves, and their little Convoy did so bestir them, that Sir Robert, although he shifted his Ship, fell foul on his best Friends, and did all that was possible, unless he could have multiplied himself, and been every where, was forced to give it over, and all the Prize that was gotten, sufficed not to pay the Chirurgeons and Carpenters.

To descend to the very bottom of their hellish Conspiracy, there was yet one step more; that of Religion. For so pious and just an Action as Sir Robert Holmes was imployed upon, could not be better accompanied than by the Declaration of Liberty of Conscience (unless they should have expected till he had found that pretious Commodity in plundering the Hoale of some Amsterdam Fly-boat) Accordingly, while he was trying his Fortune in Battle with the Smyrna Merchant-Men, on the thirteenth and fourteenth of March, One thousand six hundred seventy two, the Indulgence was Printing off here in all haste, and was Published on the fifteenth, as a more proper means than Fasting and Prayer for propitiating Heaven to give Success to his Enterprise, and to the War that must second it.

Hereby, all the Penal Laws against Papists, for which former Parliaments had given so many Supplies, and against Nonconformists, for which this Parliament had payd more largly, were at one Instant Suspended, in order to defraud the Nation of all that Religion which they had so dearly purchased, and for which they ought at least, the Bargain being broke, to have been re-imbursed.

There is, I confess, a measure to be taken in those things, and it is indeed to the great reproach of Humane Wisdom, that no man has for so many Ages been able or willing to find out the due temper of Government in Divine Matters. For it appears at the first sight, that men ought to enjoy the same Propriety and Protection in their Consciences, which they have in their Lives, Liberties, and Estates: But that to take away these in Penalty for the other, is meerly a more Legal [34] and Gentile way of Padding upon the Road of Heaven, and that it is only for want of Money and for want of Religion that men take those desperate Courses.

Nor can it be denied that the Original Law upon which Christianity at the first was founded, does indeed expresly provide against all such severity. And it was by the Humility, Meekness, Love, Forbearance and Patience which were part of that excellent Doctrine, that it became at last the Universal Religion, and can no more by any other meanes be preserved, than it is possible for another Soul to animate the same Body.

But, with shame be it spoken, the Spartans obliging themselves to Lycargus his Laws, till he should come back again, continued under his most rigid Discipline, above twice as long as the Christians did endure under the gentelest of all Institutions, though with far more certainty expecting the return of their Divine Legislater Insomuch that it is no great Adventure to say, That the World was better ordered under the Antient Monarchies and Commonwealths, that the number of Virtuous men was then greater, and that the Christians found fairer quarter under those, than among themselves, nor hath there any advantage acrued unto mankind from that most perfect and practical Moddel of Humane Society, except the Speculation of a better way to future Happiness, concerning which the very Guides disagree, and of those few that follow, it will suffer no man to pass without paying at their Turn-pikes. All which had proceeded from no other reason, but that men in stead of squaring their Governments by the Rule of Christianity, have shaped Christianity by the Measures of their Government, have reduced that streight Line by the crooked, and bungling Divine and Humane things together, have been alwayes hacking and hewing one another, to frame an irregular Figure of Political Incongruity.

For wheresoever either the Magistrate, or the Clergy, or [35] the People could gratify their Ambition, their Profit, or their Phanfie by a Text improved or misapplied, that they made use of though against the consent sense and immutable precepts of Scipture, and because Obedience for Conscience sake was there prescribed, the lesse Conscience did men make in Commanding; so that several Nations have little else to shew for their Christiainity (which requires Instruction only and Example) but a pracell of sever Laws concerning Opinion or about the Modes of Worship, not so much in order to the Power of Religion as over it. Neverthelesse because Mankind must be governed some way and be held up to one Law or other, either of Christs or their own making, the vigour of such humane Constitutions is to be preserved untill the same Authority shall upon better reason revoke them; and as in the mean time no private man may without the guilt of Sedition or Rebellion resist, so neither by the Nature of the English Foundation can any Publick Person suspend them without committing an Errour which is not the lesse for wanting a legall name to expresse it. But it was the Master-peice therefore of boldnesse and contrivance in these Conspiratours to issue this Declaration, and it is hard to say wherein they took the greater felicity, whither in suspending hereby all the Statutes against Popery, that it might thence forward passe like current money over the Nation, and no man dare to refuse it, or whether gaining by this a President to suspend as well all other Laws that respect the Subjects Propriety, and by the same power to abrogate and at last inact what they pleased, till there should be no further use for the Consent of the People in Parliament.

Having been thus true to their great designe and made so considerable a progresse, they advanced with all expedition. It was now high time to Declare the War, after they had begun it; and therefore by a Manifesto of the seventeenth of March 1672, the pretended Causes were made publich [36] which were, The not having Vailed Bonnet to the English Yatch: though the Duch had all along, both at home and here as carefully endevoured to give, as the English Minestrs to avoid the receiving of all satisfaction, or letting them understand what would do it, and the Council Clock was on purpose set forward lest, their utmost Compliance in the Flag at the hour appointed, should prevent the Declaration of War by some minuts. The detaining of some few English families (by their own Consent) in Surynam after the Dominion of it was by Treaty surrendred up to the Hollander, in which they had likewise constantly yielded to the unreasonable demands that were from one time to another extended from hence to make the thing impracticable, till even Banister himself, that had been imployed as the Agent and Contriver of this misunderstanding, could not at the last forbear to cry shame of it. And moreover to fill up the measure of the Dutch iniquity, they are accused of Pillars, Medalls, and Pictures: a Poet indeed, by a dash of his Pen, having once been the cause of a Warre against Poland; but this certainely was the first time that ever a Painter could by a stroke of his Pencill occasion the Breach of a Treaty. But considering the weaknesse and invalidity of those other allegations, these indeed were not unnecessary, the Pillars to adde strength, the Meddalls Weight, and the Pictures Colour to their Reasons.

But herein they had however observed Faith with France though on all other sides broken, having capitulated to be the first that should do it. Which as it was no small peice of French Courtesey in so important an action to yield the English the Precedence, so was it on the English part as great a Bravery in accepting to be the formost to discompose the State of all Christendom, and make themselves principal to all the horrid Destruction, Devastation, Ravage and Slaughter, [37] which from that fatal seventeenth of March, One thousand six hundred seventy two, has to this very day continued.

But that which was most admirable in the winding up of this Declaration, was to behold these Words,

And whereas we are engaged by a Treaty to support the Peace made at Aix la Chapelle; We do finally Declare, that, notwithstanding thé Prosecution of this War, We will maintain the true intent and scope of the said Treaty, and that, in all Alliances, which We have, or shall make in the progress of this War, we have, and will take care, to preserve the ends thereof inviolable, unless provoked to the contrary.

And yet it is as clear as the Sun, that the French had by that Treaty of Aix la Chapelle, agreed to acquiess in their former Conquests in Flanders, and that the English, Swede and Hollander, were reciprocally bound to be aiding against whomsoever should disturbe that Regulation, (besides the League Offensive and Defensive, which his Majesty had entered into with the States General of the United Provinces) all which was by this Conjunction with France to be broken in pieces. So that what is here declared, if it were reconcileable to Truth, yet could not consist with Possibility (which two do seldom break company) unless by one only Expedient, that the English, who by this new League with France, were to be the Infractors and Aggressors of the Peace of Aix la Chapelle (and with Holland) should to fulfill their Obligations to both Parties, have sheathed the Sword in our own Bowels.

But such was the Zeal of the Conspirators, that it might easily transport them either to say what was untrue, or undertake what was impossible, for the French Service.

[38]

That King having seen the English thus engaged beyond a Retreat, comes now into the War according to agreement. But he was more Generous and Monarchal than to assign Cause, true or false, for his Actions. He therefore, on the 27th. of March 1672, publishes a Declaration of War without any Reasons. Only, The ill satisfaction which his Majesty hath of the Behaviour of the States General towards him, being risen to that degree, that he can no longer, without diminution to his Glory dissemble his Indignation against them, &c. Therefore he hath resolved to make War against them both by Sea and Land, &c. And commands all his Subjects, Courir sus, upon the Hollauders, (a Metaphor which, out of respect to his own Nation, might have been spared) For such is our pleasure.

Was ever in any Age or Nation of the World, the Sword drawn upon no better Allegation? A stile so far from being Most Christian, that nothing but some vain French Romance can parallel or justify the Expression. How happy were it could we once arrive at the same pitch, and how much credit and labour had been saved, had the Compilers of our Declaration, in stead of the mean English way of giving Reasons, contented themselves with that of the Diminution of the English Honour, as the French of his Glory! But nevertheless, by his Embassador to the Pope, he gave afterwards a more clear account of his Conjunction with the English, and that he had not undertaken this War, against the Hollanders, but for extirpating of Heresie. To the Emperour, That the Hollanders were a People who had forsaken God, were Hereticks, and that all good Christians were in duty bound to associate for their extiapation, and ought to pray to God for a blessing upon so pious an enterprise. And to other Popish Princes, that it was a War of Religion and in order to the Propagation of the Catholick Faith.

And in the second Article of his Demands afterward from the Hollanders, it is in express words contained, That from [39] thenceforward there shall be not only an intire Liberty, but a Publick Exercise of the Catholick Apostolick Romane Religion throughout all the United Provinces. So that wheresoever there shall be more than one-Church, another shall be given to the Catholicks. That where there is none, they shall be permitted to build one: and till that be finished, to exercise their Divine Service publickly in such Houses as they shall buy, or hire for that purpose. That the States General, or each Province in particular, shall appoint a reasonable Salary for a Curate or Priest in each of the said Churches, out of such Revenues as have formerly appertained to the Church, or otherwise. Which was conformable to what he published now abroad, that he had entered into the War only for Gods Glory; and that he would lay down Armes streightwayes, would the Hollanders but restore the True Worship in their Dominions.

But he made indeed twelve Demands more, and notwithstanding all this devotion, the Article of Commerce, and for revoking their Placaets against Wine, Brandy, and French manufactures was the first, and tooke place of the Catholick Apostolick Romane Religion, Whether all these were therefore onely words of course, and to be held or let lose according to his occasions, will better appeare when we shall have heard that he still insists upon the same at Nimegen, and that, although deprived of our assistance, he will not yet agree with the Dutch but upon the termes of restoring the True Worship. But, whatever he were, it is evident that the English were sincere and in good earnest in the Design of Popery; both by that Declaration above mentioned of Indulgence to the Recusants, and by the Negotiation of those of the English Plenipotentiaryes (whom for their honour I name not) that being in that year sent into Holland pressed that Article among the rest upon them, as without which they could have no hope of Peace with England. And the whole processe of affaires will manifest further that booth here and there it was all of a piece, as to the project of Religion [40] and the same threed ran throw the Web of the English and French Counsells, no lesse in relation to that, then unto Government.

Although the issuing of the French Kings declaration and the sending of our English Plenipotentiaries into Holland be involved together in this last period, yet the difference of time was so small that the anticipation is inconsiderable. For having declared the VVarre but on the 27th of March, 1672. He struck so home and followed his blow so close, that by July following, it seemed that Holland could no longer stand him, but that the swiftnesse and force of his motion was something supernatural. And it was thought necessary to send over those Plenipotentiaries, if not for Interest yet at least for Curiosity. But it is easier to find the Markes than Reasons of some mens Actions, and he that does only know what happened before, and what after, might perhaps wrong them by searching for further Intelligence.

So it was, that the English and French Navies being joyned, were upon the Twentieighth of May, One thousand six hundred seventy two, Attaqued in Soule Bay by De Ruyter, with too great advantage. For while his Royal Highness, then Admiral, did all that could be expected, but Monsieur d' Estree, that commanded the French, did all that he was sent for, Our English Vice-Admiral, Mountague, was sacrificed; and the rest of our Fleet so mangled, that there was no occasion to boast of Victory. So that being here still on the losing hand, 'twas fit some body should look to the Betts on the other side of the Water; least that Great and Lucky Gamster, when he had won all there, and stood no longer in need of the Conspirators, should pay them with a Quarrel for his Mony, and their ill Fortune. Yet were they not conscious to themselves of having given him by any Behaviour of theirs, any cause of Dissatisfaction, but that they had dealt with him in all things most frankly, That, notwithstanding all the Expressions in my Lord Keeper Bridgmans Speech, [41] of the Treaty between France and his Majesty concerning Commerce, wherein his Majesty will have a singular regard to the Honour and also to the Trade of this Nation, and notwithstanding the intollerable oppressions upon the English Traffick in France ever since the Kings Restauration, they had not in all that time made one step towards a Treaty of Commerce or Navigation with him; no not even now when the English were so necessary to him, that he could not have begun this War without them, and might probably therefore in this conjuncture have condescended to some equality. But they knew how tender that King was on that point, and to preserve and encrease the Trade of his Subjects, and that it was by the Diminution of that Beam of his Glory, that the Hollanders had raised his Indignation. The Conspirators had therefore, the more to gratify him, made it their constant Maxime, to burden the English Merchant here with one hand, while the French should load them no less with the other, in his Teritories; which was a parity of Trade indeed, though something an extravagant one, but the best that could be hoped from the prudence and integrity of our States-men; insomuch, that when the Merchants have at any time come down from London to represent their grievances from the French, to seek redress, or offer their humble advice, they were Hector'd, Brow-beaten, Ridiculed, and might have found fairer audience even from Monsieur Colbert.

They knew moreover, that as in the matter of Commerce, so they had more obliged him in this War. That except the irresistable bounties of so great a Prince in their own particular, and a frugal Subsistance-money for the Fleet, they had put him to no charges, but the English Navy Royal serv'd him, like so many Privateers, No Purchase, No Pay. That in all things they had acted with him upon the most abstracted Principles of Generosity. They had tyed him to no [42] terms, had demanded no Partition of Conquests, had made no humane Condition; but had sold all to him for those two Pearls of price, the True Worship, and the True Government: Which disinteressed proceeding of theirs, though suited to Forraine Magnanimity, yet, should we still lose at Sea, as we had hitherto, and the French Conquer all at Land, as it was in prospect, might at one time or other breed some difficulty in answering for it to the King and Kingdom: However this were, it had so hapned before the arrival of the Plenipotentiaries, that, whereas here in England, all that brought applycations from Holland were treated as Spies and Enemies, till the French King should signify his pleasure; he on the contrary, without any communication here, had received Addresses from the Dutch Plenipotentiaries, and given in to them the sum of his Demands (not once mentioning his Majesty or his Interest, which indeed he could not have done unless for mockery, having demanded all for himself, so that there was no place left to have made the English any satisfaction) and the French Ministers therefore did very candidly acquaint those of Holland, that, upon their accepting those Articles, there should be a firm Peace, and Amity restored: But as for England, the States, their Masters, might use their discretion, for that France was not obliged by any Treaty to procure their advantage.

This manner of dealing might probably have animated, as it did warrant the English Plenipotentiaries, had they been as full of Resolution as of Power, to have closed with the Dutch, who, out of aversion to the French, and their intollerable demands, were ready to have thrown themselves into his Majesties Armes, or at his Feet, upon any reasonable conditions; But it wrought clean otherwise: For, those of the English Plenipotentiaries, who were, it seems, intrusted with a fuller Authority, and the deeper Secret, gave in also the English Demands to the Hollanders, consisting in eight Articles, but at last the Ninth saith,

[43]

Although his Majesty contents himself with the foregoing Conditions, so that they be accepted within ten dayes, after which his Majesty understands himself to be no further obliged by them. He declares nevertheless precisely, that albeit they should all of them be granted by the said States, yet they shall be of no force, nor will his Majesty make any Treaty of Peace or Truce, unless the Most Christian King shall have received satisfastion from the said States in his particular.

And by this means they made it impossible for the Dutch, however desirous, to comply with England, excluded us from more advantagious terms, than we could at any other time hope for, and deprived us of an honest, and honourable evasion out of so pernicious a War, and from a more dangerous Alliance. So that now it appeared by what was done that the Conspirtors securing their own fears at the price of the Publick Interest, and Safety, had bound us up more strait then ever, by a new Treaty, to the French Project.

The rest of this year passed with great successe to the French, but none to the English. And therefore the hopes upon which the War was begun, of the Smyrna and Spanish Fleet, and Dutch Prizes, being vanished, the slender Allowance from the French not sufficing to defray it, and the ordinary Revenue of the King, with all the former Aides being (as was fit to be believed) in lesse then one years time exhausted, The Parliament by the Conspirators good leave, was admitted again to sit at the day appointed, the 4th. of February 1672.

The Warr was then first communicated to them, and the Causes, the Necessity, the Danger, so well Painted out, that the Dutch abusive Historical Pictures, and False Medalls (which were not forgot to be mentioned) could not be better imitated or revenged, Onely, there was one great omission of their False Pillars, which upheld the whole Fabrick of the England Declarations; Upon this signification, the House of Commons (who had never failed the Crown hitherto upon [44] any occosion of mutual gratuity) did now also, though in a Warre contrary to former usuage, begun without their Advice, readily Vote, no less a summe than 1250000 l. But for better Colour, and least they should own in words, what they did in effect, they would not say it was for the Warre, but for the Kings Extraordinary Occasions.

And because the Nation began now to be aware of the more true Causes, for which the Warre had been undertaken, they prepared an Act before the Money-Bill slipt thorrow their Fingers, by which the Papists were obliged, to pass thorow a new State Purgatory, to be capable of any Publick Imployment; whereby the House of Commons, who seem to have all the Great Offices of the Kingdom in Reversion, could not but expect some Wind-falls.

Upon this Occasion it was, that the Earl of Shaftsbury, though then Lord Chancellour of England, yet, Engaged so far in Defence of that ACT, and of the PROTESTANT RELIGION, that in due time it cost him his Place, and was the first moving Cause of all those Misadventures, and Obloquy, which since he lyes (ABOVE, not) Under.

The Declaration also of Indulgence was questioned, which, though his MAJESTY had out of his Princely, and Gracious Inclination, and the memory of some former Obligations, granted, yet upon their Representation of the Inconveniencies, and at their humble Request, he was pleased to Cancel, and Declare, that it should be no President for the Future: For otherwise some succeeding Governour, by his single Power Suspending Penal Laws, in a favourable matter, as that is of Religion, might become more dangerous to the Government, than either Papists or Fanaticks, and [45] make us Either, when he pleased: So Legal was it in this Session to Distinguish between the King of Englands Personal, and his Parliamentary Authority.

But therefore the further sitting being grown very uneasie to those, who had undertaken for the Change of Religion, and Government, they procured the Recess so much sooner, and a Bill sent up by the Commons in favour of Dissenting Protestants, not having passed thorow the Lords preparation, the Bill concerning Papists, was enacted in Exchange for the Money, by which the Conspiraiors, when it came into their management, hoped to frustrate, yet, the effect of the former. So the Parliament was dismissed till the Twenty seventh of October, One thousand six hundred seventy three.