JOHN MILTON,

Eikonoklestēs in answer to a book intitl'd Eikōn basilikē the portrature His Sacred Majesty in his solitudes and sufferings (1650)

|

[Created: 23 May, 2023]

[Updated: May 23, 2023 ] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

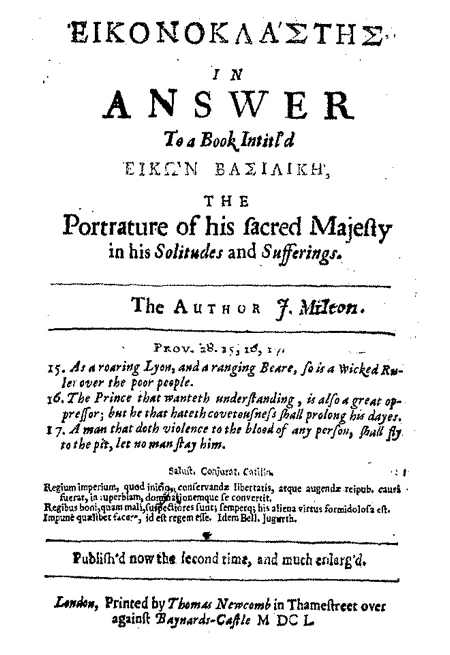

, ΕΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ in answer to a Book intitl’d ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ, The Portrature of his sacred Majesty in his Solitudes and Sufferings. Publish’d now the second time, and much enlarg’d. (London, Thomas Newcomb, 1650).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1650-Milton_Eikonoklastes/Milton_Eikonoklastes1650-ebook.html

John Milton, ΕΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ in answer to a Book intitl’d ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ, The Portrature of his sacred Majesty in his Solitudes and Sufferings. The Author J. Milton. Publish’d now the second time, and much enlarg’d. (London, Printed by Thomas Newcomb in Thamestreet over against Baynards-Castle M DC L. (1650)).

PROV. 28. 15, 16, 17.

15. As a roaring Lyon, and a ranging Beare, so is a wicked Ruler over the poor people.

16. The Prince that wanteth understanding, is also a great oppressor; but he that hateth covetousness shall prolong his dayes.

17. A man that doth violence to the blood of any person, shall fly to the pit, let no man stay him.

Salust. Conjurat. Catilin.

Regiam imperium, quod initio, conservandae libertatis, atque augendae reipub. causâ fuerat, in superbiam, dominationemque se convertit.

Regibus boni, quam mali, suspectiores sunt; semperque his aliena virtus formidolosa est.

Impunè quaelibet facere, id est regem esse. Idem Bell. Jugurth.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted short margin notes to float right

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Contents

ΕΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ.

- I. Upon the Kings calling this last Parlament.

- II. Upon the Earle of Straffords Death.

- III. Upon his going to the House of Commons.

- IV. Vpon the Insolency of the Tumults.

- V. Upon the Bill for Trienniall Parlaments, And for setling this &c.

- VI. Upon his Retirement from Westminster.

- VII. Vpon the Queens departure.

- VIII. Upon His repulse at Hull, and the fate of the Hothams.

- IX. Upon the listing and raising Armies, &c.

- X. Upon their seizing the Magazins, Forts, &c.

- XI. Upon the Nineteen Propositions, &c.

- XII. Vpon the Rebellion in Ireland.

- XIII. Upon the calling in of the Scots and thir comming.

- XIIII. Upon the Covnant.

- XV. Upon the many Jealousies, &c.

- XVI. Vpon the Ordinance against the Common-Prayer Book.

- XVII. Of the differences in point of Church-Goverment.

- XVIII. Upon the Uxbridge Treaty, &c.

- XIX. Vpon the various events of the Warr.

- XX. Upon the Reformation of the times.

- XXI. Vpon His Letters tak'n and divulg'd.

- XXII. Vpon His going to the Scots.

- XXIII. Vpon the Scots delivering the King to the English.

- XXIV. Vpon the denying him the attendance of his Chaplains

- XXV. Vpon His penitentiall Meditations and Vowes at Holmby

- XXVI. Vpon the Armies surprisall of the King at Holmeby.

- XXVII. Intitil'd to the Prince of Wales.

- XXVIII. Intitl'd Meditations upon Death.

The PREFACE.↩

TO descant on the misfortunes of a person fall'n from so high a dignity, who hath also payd his final debt both to Nature and his Faults, is neither of it self a thing commendable, nor the intention of this discours. Neither was it fond ambition, or the vanity to get a Name, present; or with Posterity, by writing against a King: I never was so thirsty after Fame, nor so destitute of other hopes and means, better and more certaine to attaine it. For Kings have gain'd glorious Titles from thir Fovourers by writing against privat men, as Henry the 8th did against Luther; but no man ever gain'd much honour by writing against a King, as not usually meeting with that force of Argument in such Courtly Antagonists, which to convince might add to his reputation. Kings most commonly, though strong in Legions, are but weak at Arguments; as they who ever have accustom'd from the Cradle to use thir will onely as thir right hand, thir reason alwayes as thir left. Whence unexpectedly constrain'd to that kind of combat, they prove but weak and puny Adversaries. Nevertheless for their sakes who through custom, simplicitie, or want of better teaching, have not more seriously considerd Kings, then in the gaudy name of Majesty, and admire them and thir doings, as if they breath'd [Page] not the same breath with other mortal men, I shall make no scruple to take up (for it seems to be the challenge both of him and all his party) to take up this Gauntlet, though a Kings, in the behalf of Libertie, and the Common-wealth.

And furder, since it appears manifestly the cunning drift of a factious and defeated Party, to make the same advantage of his Book, which they did before of his Regal Name and Authority, and intend it not so much the defence of his former actions, as the promoting of thir own future designes, making thereby the Book thir own rather then the Kings, as the benefit now must be thir own more then his, now the third time to corrupt and disorder the mindes of weaker men, by new suggestions and narrations, either falsly or fallaciously representing the state of things, to the dishonour of this present Goverment, and the retarding of a generall peace, so needfull to this afflicted Nation, and so nigh obtain'd, I suppose it no injurie to the dead, but a good deed rather to the living, if by better information giv'n them, or, which is anough, by onely remembring them the truth of what they themselves know to be heer misaffirm'd, they may be kept from entring the third time unadvisedly into Warr and bloodshed. For as to any moment of solidity in the Book it self, save only that a King is said to be the Author, a name, then which there needs no more among the blockish vulgar, to make it wise, and excellent, and admir'd, nay to set it next the Bible, though otherwise containing little els but the common grounds of tyranny and popery, drest up, the better to deceiv, in a new Protestant guise, [Page] and trimmly garnish'd over, or as to any need of answering, in respect of staid and well-principl'd men, I take it on me as a work assign'd rather, then by me chos'n or affected. Which was the cause both of beginning it so late, and finishing it so leasurely, in the midst of other imployments and diversions. And though well it might have seem'd in vaine to write at all; considering the envy and almost infinite prejudice likely to be stirr'd up among the Common sort, against what ever can be writt'n or gainsaid to the Kings book, so advantageous to a book it is, only to be a Kings, and though it be an irksom labour to write with industrie and judicious paines that which neither waigh'd, nor well read, shall be judg'd without industry or the paines of well judging, by faction and the easy literature of custom and opinion, it shall be ventur'd yet, and the truth not smother'd, but sent abroad, in the native confidence of her single self, to earn, how she can, her entertainment in the world, and to finde out her own readers; few perhaps, but those few, such of value and substantial worth, as truth and wisdom, not respecting numbers and bigg names, have bin ever wont in all ages to be contented with.

And if the late King had thought sufficient those Answers and Defences made for him in his life time, they who on the other side accus'd his evil Goverment, judging that on their behalf anough also hath been reply'd, the heat of this controversie was in likelyhood drawing to an end; and the furder mention of his deeds, not so much unfortunat as faulty, had in tenderness to his late sufferings, bin willingly forborn; and perhaps for the [Page] present age might have slept with him unrepeated; while his adversaries, calm'd and asswag'd with the success of thir cause, had bin the less unfavorable to his memory. But since he himself, making new appeale to Truth and the World, hath left behind him this Book as the best advocat and interpreter of his own actions, and that his Friends by publishing, dispersing, commending, and almost adoring it, seem to place therein the chiefe strength and nerves of thir cause, it would argue doubtless in the other party great deficience and distrust of themselves, not to meet the force of his reason in any field whatsoever, the force and equipage of whose Armes they have so oft'n met victoriously. And he who at the Barr stood excepting against the form and manner of his Judicature, and complain'd that he was not heard, neither he nor his Friends shall have that cause now to find fault; being mett and debated with in this op'n and monumental Court of his own erecting; and not onely heard uttering his whole mind at large, but answer'd. Which to doe effectually, if it be necessary that to his Book nothing the more respect be had for being his, they of his own Party can have no just reason to exclaime. For it were too unreasonable that he, because dead, should have the liberty in his Book to speak all evil of the Parlament; and they, because living, should be expected to have less freedom, or any for them, to speak home the plain truth of a full and pertinent reply. As he, to acquitt himself, hath not spar'd his Adversaries, to load them with all sorts of blame and accusation, so to him, as in his Book alive, there will be us'd no more Courtship then he uses; but [Page] what is properly his own guilt, not imputed any more to his evil Counsellors, (a Cerèmony us'd longer by the Parlament then he himself desir'd) shall be laid heer without circumlocutions at his own dore. That they who from the first beginning, or but now of late, by what unhappines I know not, are so much affatuated, not with his person onely, but with his palpable faults, and dote upon his deformities, may have none to blame but thir own folly, if they live and dye in such a strook'n blindness, as next to that of Sodom hath not happ'nd to any sort of men more gross, or more misleading. Yet neither let his enemies expect to finde recorded heer all that hath been whisper'd in the Court, or alleg'd op'nly of the Kings bad actions; it being the proper scope of this work in hand, not to ripp up and relate the misdoings of his whole life, but to answer only, and refute the missayings of his book.

First then that some men (whether this were by him intended, or by his Friends) have by policy accomplish'd after death that revenge upon thir Enemies, which in life they were not able, hath been oft related. And among other examples we finde that the last will of Caesar being read to the people, and what bounteous Legacies hee had bequeath'd them, wrought more in that Vulgar audience to the avenging of his death, then all the art he could ever use, to win thir favor in his life-time. And how much their intent, who publish'd these overlate Apologies and Meditations of the dead King, drives to the same end of stirring up the people to bring him that honour, that affection, and by consequence, that revenge to his dead Corps, which hee himself [Page] living could never gain to his Person, it appears both by the conceited portraiture before his Book, drawn out to the full measure of a Masking Scene, and sett there to catch fools and silly gazers, and by those Latin words after the end, Vota dabunt qua Bella negarunt; intimating, That what hee could not compass by Warr, he should atchieve by his Meditations. For in words which admitt of various sense, the libertie is ours to choose that interpretation which may best minde us of what our restless enemies endeavor, and what wee are timely to prevent. And heer may be well observ'd the loose and negligent curiosity of those who took upon them to adorn the setting out of this Book: for though the Picture sett in Front would Martyr him and Saint him to befool the people, yet the Latin Motto in the end, which they understand not, leaves him, as it were a politic contriver to bring about that interest by faire and plausible words, which the force of Armes deny'd him. But quaint Emblems and devices begg'd from the old Pageantry of some Twelf-nights entertainment at Whitehall, will doe but ill to make a Saint or Martyr: and if the People resolve to take him Sainted at the rate of such a Canonizing, I shall suspect thir Calendar more then the Gregorian. In one thing I must commend his op'nness who gave the title to this Book, ΕΙΚΩΝ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ, that is to say, The Kings Image; and by the Shrine he dresses out for him, certainly would have the people come and worship him. For which reason this answer also is intitl'd Iconoclastes, the famous Surname of many Greek Emperors, who in thir zeal to the command of God, after long tradition of Idolatry [Page] in the Church, took courage, and broke all superstitious Images to peeces. But the People, exorbitant and excessive in all thir motions, are prone ofttimes not to a religious onely, but to a civil kinde of Idolatry in idolizing thir Kings; though never more mistak'n in the object of thir worship; heretofore being wont to repute for Saints, those faithful and courageous Barons, who lost thir lives in the Field, making glorious Warr against Tyrants for the common Liberty; as Simon de Momfort Earl of Leicester, against Henry the third; Thomas Plantagenet Earl of Lancaster, against Edward the second. But now, with a besotted and degenerate baseness of spirit, except some few, who yet retain in them the old English fortitude and love of Freedom, and have testifi'd it by thir matchless deeds, the rest, imbastardiz'd from the ancient nobleness of thir Ancestors, are ready to fall flatt and give adoration to the Image and Memory of this Man, who hath offer'd at more cunning fetches to undermine our Liberties, and putt Tyranny into an Art, then any British King before him. Which low dejection and debasement of mind in the people, I must confess I cannot willingly ascribe to the natural disposition of an English-man, but rather to two other causes. First, to the Prelats and thir fellow-teachers, though of another Name and Sect, whose Pulpit stuff, both first and last, hath bin the Doctrin and perpetual infusion of servility and wretchedness to all thir hearers; whose lives the type of worldliness and hypocrisie, without the least tiue pattern of vertue, righteousness, or self-denial in thir whole practice. I attribute it next to the factious inclination of most men divided from the public [Page] by several ends and humors of thir own. At first no man less belov'd, no man more generally condemn'd then was the King; from the time that it became his custom to break Parlaments at home, and either wilfully or weakly to betray Protestants abroad, to the beginning of these Combustions. All men inveigh'd against him; all men, except Courtvassals, oppos'd him and his tyrannical proceedings; the cry was universal; and this full Parlament was at first unanimous in thir dislike and Protestation against his evil Goverment. But when they who sought themselves and not the Public, began to doubt that all of them could not by one and the same way attain to thir ambitious purposes, then was the King, or his Name at least, as a fit property, first made use of, his doings made the best of, and by degrees justifi'd: Which begott him such a party, as after many wiles and struglings with his in ward fears, imbold'n'd him at length to sett up his Standard against the Parlament. Whenas before that time, all his adherents, consisting most of dissolute Sword-men and Suburb-roysters, hardly amounted to the making up of one ragged regiment strong anough to assault the unarmed house of Commons. After which attempt, seconded by a tedious and bloody warr on his subjects, wherein he hath so farr exceeded those his arbitrary violences in time of Peace, they who before hated him for his high misgoverment, nay, fought against him with display'd banners in the field, now applaud him and extoll him for the wisest and most religious Prince that liv'd. By so strange a method amongst the mad multitude is a sudden reputation won, of wisdom by wilfulness and suttle [Page] shifts, of goodness by multiplying evil, of piety by endeavouring to root out true religion.

But it is evident that the chief of his adherents never lov'd him, never honour'd either him or his cause, but as they took him to set a face upon thir own malignant designes; nor bemoan his loss at all, but the loss of thir own aspiring hopes: Like those captive women whom the Poet notes in his Iliad, to have bewaild the death of Patroclus in outward show, but indeed thir own condition.

Hom. Iliad.

And it needs must be ridiculous to any judgement uninthrall'd, that they who in other matters express so little fear either of God or man, should in this one particular outstripp all precisianism with thir scruples and cases, and fill mens ears continually with the noise of thir conscientious Loyaltie and Allegeance to the King, Rebels in the mean while to God in all thir actions beside: much less that they whose profess'd Loyalty and Allegeance led them to direct Arms against the Kings Person, and thought him nothing violated by the Sword of Hostility drawn by them against him, should now in earnest think him violated by the unsparing Sword of Justice, which undoubtedly so much the less in vain she bears among Men, by how much greater and in highest place the offender. Els Justice, whether moral or political, were not Justice, but a fals counterfet of that impartial and Godlike vertue. The onely grief is, that the head was not strook off to the best advantage [Page] and commodity of them that held it by the hair; an ingratefull and pervers generation, who having first cry'd to God to be deliver'd from thir King, now murmur against God that heard thir praiers, and cry as loud for thir King against those that deliver'd them. But as to the Author of these Soliloquies, whether it were undoubtedly the late King, as is vulgarly beleev'd, or any secret Coadjutor, and some stick not to name him, it can add nothing, nor shall take from the weight, if any be, of reason which he brings. But allegations, not reasons are the main contents of this Book, and need no more then other contrary allegations to lay the question before all men in an eev'n ballance; though it were suppos'd that the testimony of one man in his own cause affirming, could be of any moment to bring in doubt the autority of a Parlament denying. But if these his fair spok'n words shall be heer fairly confronted and laid parallel to his own farr differing deeds, manifest and visible to the whole Nation, then surely we may look on them who notwithstanding shall persist to give to bare words more credit then to op'n deeds, as men whose judgement was not rationally evinc'd and perswaded, but fatally stupifi'd and bewitch'd, into such a blinde and obstinate beleef. For whose cure it may be doubted, not whether any charm, though never so wisely murmur'd, but whether any prayer can be available. This however would be remember'd and wel noted, that while the K. instead of that repentance which was in reason and in conscience to be expected from him, without which we could not lawfully re-admitt him, persists heer to maintain and justifie the most apparent [Page] of his evil doings, and washes over with a Courtfucus the worst and foulest of his actions, disables and uncreates the Parlament it self, with all our laws and Native liberties that ask not his leave, dishonours and attaints all Protestant Churches, not Prelaticall, and what they piously reform'd, with the slander of rebellion, sacrilege, and hypocrisie; they who seem'd of late to stand up hottest for the Cov'nant, can now sit mute and much pleas'd to hear all these opprobrious things utter'd against thir faith, thir freedom, and themselves in thir own doings made traitors to boot: The Divines also, thir wizzards, can be so braz'n as to cry Hosanna to this his book, which cries louder against them for no disciples of Christ, but of Iscariot; and to seem now convinc'd with these wither'd arguments and reasons heer, the same which in som other writings of that party, and in his own former Declarations and expresses, they have so oft'n heertofore endeavour'd to confute and to explode; none appearing all this while to vindicate Church or State from these calumnies and reproaches, but a small handfull of men whom they defame and spit at with all the odious names of Schism and Sectarism. I never knew that time in England, when men of truest Religion were not counted Sectaries: but wisdom now, valor, justice, constancy, prudence united and imbodied to defend Religion and our Liberties, both by word and deed against tyranny, is counted Schism and faction. Thus in a graceless age things of highest praise and imitation under a right name, to make them infamous and hatefull to the people, are miscall'd. Certainly, if ignorance and perversness will [Page] needs be national and universal, then they who adhere to wisdom and to truth, are not therfore to be blam'd, for beeing so few as to seem a sect or faction. But in my opinion it goes not ill with that people where these vertues grow so numerous and well joyn'd together, as to resist and make head against the rage and torrent of that boistrous folly and superstition that possesses and hurries on the vulgar sort. This therefore we may conclude to be a high honour don us from God, and a speciall mark of his favor, whom he hath selected as the sole remainder, after all these changes and commotions, to stand upright and stedfast in his cause; dignify'd with the defence of truth and public libertie; while others who aspir'd to be the topp of Zelots, and had almost brought Religion to a kinde of trading monopoly, have not onely by thir late silence and neutrality bely'd thir profession, but founder'd themselves and thir consciences, to comply with enemies in that wicked cause and interest which they have too oft'n curs'd in others, to prosper now in the same themselves.

[1]

ΕΙΚΟΝΟΚΛΑΣΤΗΣ

I. Upon the Kings calling this last Parlament.↩

THat which the King layes down heer as his first foundation, and as it were the head stone of his whole Structure, that He call'd this last Parlament not more by others advice and the necessity of his affaires, then by his own chois and inclination, is to all knowing men so apparently not true, that a more unlucky and inauspicious sentence, and more betok'ning the downfall of his whole Fabric, hardly could have come into his minde. For who knows not that the inclination of a Prince is best known either by those next about him, and most in favor with him, or by the current of his own actions. Those neerest to this King and most his Favorites, were Courtiers and Prelates; men whose chief study was to finde out which way the King inclin'd, and to imitate him exactly. How these men stood affected to Parlaments, cannot be forgott'n. No man but may remember it was thir continuall exercise to dispute and preach against them; and in thir common discours nothing was more frequent, then that they hoped the King should now have no need of Parlaments any more. And this was but the copy which his Parasites had industriously tak'n from his own words and actions, who never call'd a Parlament but to supply his necessities; and having supply'd those, as suddenly [2] and ignominiously dissolv'd it, without redressing any one greevance of the people. Somtimes choosing rather to miss of his Subsidies, or to raise them by illegal courses, then that the people should not still miss of thir hopes to be releiv'd by Parlaments.

The first he broke off at his comming to the Crown; for no other cause then to protect the Duke of Buckingham against them who had accus'd him, besides other hainous crimes, of no less then poysoning the deceased King his Father; concerning which matter the Declaration of No more addresses, hath sufficiently inform'd us. And still the latter breaking was with more affront and indignity put upon the House and her worthiest Members, then the former: Insomuch that in the fifth year of his Raign, in a Proclamation he seems offended at the very rumor of a Parlament divulg'd among the people: as if he had tak'n it for a kind of slander, that men should think him that way exorable, much less inclin'd: and forbidds it as a presumption to prescribe him any time for Parlaments, that is to say, either by perswasion or Petition, or so much as the reporting of such a rumor; for other manner of prescribing was at that time not suspected. By which feirce Edict, the people, forbidd'n to complain, as well as forc'd to suffer, began from thenceforth to despaire of Parlaments. Whereupon such illegal actions, and especially to get vast summs of Money, were put in practise by the King and his new Officers, as Monopolies, compulsive Knight-hoods, Cote, Conduct and Ship money, the seizing not of one Naboths Vineyard, but of whole Inheritances [3] under the pretence of Forrest, or Crown Lands, corruption and Bribery compounded for, with impunities granted for the future, as gave evident proof that the King never meant, nor could it stand with the reason of his affaires, ever to recall Parlaments; having brought by these irregular courses the peoples interest and his own to so direct an opposition, that he might foresee plainly, if nothing but a Parlament could save the people, it must necessarily be his undoing.

Till eight or nine years after, proceeding with a high hand in these enormities, and having the second time levied an injurious Warr against his native Countrie Scotland, and finding all those other shifts of raising Money, which bore out his first expedition, now to faile him, not of his own chois and inclination, as any Child may see, but urg'd by strong necessities, and the very pangs of State, which his own violent proceedings had brought him to, hee calls a Parlament; first in Ireland, which onely was to give him four Subsidies, and so to expire; then in England, where his first demand was but twelve Subsidies, to maintain a Scotch Warr, condemn'd and abominated by the whole Kingdom; promising thir greevances should be consider'd afterward. Which when the Parlament, who judg'd that Warr it self one of thir main greevances, made no hast to grant, not enduring the delay of his impatient will, or els fearing the conditions of thir grant, he breaks off the whole Session, and dismisses them and thir greevances with scorn and frustration.

Much less therfore did hee call this last Parlament by his own chois and inclination; but having [4] first try'd in vaine all undue ways to procure Mony, his Army, of thir own accord, being beat'n in the North, the Lords Petitioning, and the general voice of the people almost hissing him and his ill acted regality off the Stage, compell'd at length both by his wants, and by his feares, upon meer extremity he summon'd this last Parlament. And how is it possible that hee should willingly incline to Parlaments, who never was perceiv'd to call them, but for the greedy hope of a whole National Bribe, his Subsidies, and never lov'd, never fulfill'd, never promoted the true end of Parlaments, the redress of greevances, but still put them off, and prolong'd them, whether gratify'd ot not gratify'd; and was indeed the Author of all those greevances. To say therfore that hee call'd this Parlament of his own chois and inclination, argues how little truth wee can expect from the sequel of this Book, which ventures in the very first period to affront more then one Nation with an untruth so remarkable; and presumes a more implicit Faith in the people of England, then the Pope ever commanded from the Romish Laitie; or els a natural sottishness fitt to be abus'd and ridd'n. While in the judgement of wise Men, by laying the foundation of his defence on the avouchment of that which is so manifestly untrue, he hath giv'n a worse foile to his own cause, then when his whole Forces were at any time overthrown. They therfore who think such great Service don to the Kings affairs in publishing this Book, will find themselves in the end mistak'n: if sense and right mind, or but any mediocrity of knowledge and remembrance hath not quite forsak'n men.

[5]

But to prove his inclination to Parlaments, he affirms heer To have always thought the right way of them, most safe for his Crown, and best pleasing to his People. What hee thought we know not; but that hee ever took the contrary way wee saw; and from his own actions we felt long agoe what he thought of Parlaments or of pleasing his People: a surer evidence then what we hear now too late in words.

He alleges, that the cause of forbearing to convene Parlaments, was the sparkes which some mens distempers there studied to kindle. They were indeed not temper'd to his temper; for it neither was the Law, nor the rule by which all other tempers were to bee try'd; but they were esteem'd and chos'n for the fittest men in thir several Counties, to allay and quench those distempers which his own inordinate doings had inflam'd. And if that were his refusing to convene, till those men had been qualify'd to his temper, that is to say, his will, we may easily conjecture what hope ther was of Parlaments, had not fear and his insatiat poverty in the midst of his excessive wealth constrain'd him.

Hee hoped by his freedom, and their moderation to prevent misunderstandings. And wherfore not by their freedom and his moderation? But freedom he thought too high a word for them; and moderation too mean a word for himself: this was not the way to prevent misunderstandings. He still fear'd passion and prejudice in other men; not in himself: and doubted not by the weight of his own reason, to counterpoyse any Faction; it being so easie for him, and so frequent, to call his obstinacy, Reason, and other mens reason, Faction. Wee in the mean while must beleive, that wisdom [6] and all reason came to him by Title, with his Crown; Passion, Prejudice, and Faction came to others by being Subjects.

He was sorry to hear with what popular heat Elections were carry'd in many places. Sorry rather that Court Letters and intimations prevail'd no more, to divert or to deterr the people from thir free Election of those men, whom they thought best affected to Religion and thir Countries Libertie, both at that time in danger to be lost. And such men they were, as by the Kingdom were sent to advise him, not sent to be cavill'd at, because Elected, or to be entertaind by him with an undervalue and misprision of thir temper, judgment, or affection. In vain was a Parlament thought fittest by the known Laws of our Nation, to advise and regulate unruly Kings, if they, in stead of hearkning to advice, should be permitted to turn it off, and refuse it by vilifying and traducing thir advisers, or by accusing of a popular heat those that lawfully elected them.

His own and his Childrens interest oblig'd him to seek and to preserve the love and welfare of his Subjects. Who doubts it? But the same interest, common to all Kings, was never yet available to make them all seek that, which was indeed best for themselves and thir Posterity. All men by thir own and thir Childrens interest are oblig'd to honestie and justice: but how little that consideration works in privat men, how much less in Kings, thir deeds declare best.

He intended to oblige both Friends and Enemies, and to exceed thir desires, did they but pretend to any modest and sober sence; mistaking the whole business of a Parlament. [7] Which mett not to receive from him obligations, but Justice; nor he to expect from them thir modesty, but thir grave advice, utter'd with freedom in the public cause. His talk of modesty in thir desires of the common welfare, argues him not much to have understood what he had to grant, who misconceav'd so much the nature of what they had to desire. And for sober sence the expresion was too mean; and recoiles with as much dishonour upon himself, to be a King where sober sense could possibly be so wanting in a Parlament.

The odium and offences which some mens rigour, or remissness iu Church and State had contracted upon his Goverment, hee resolved to have expiated with better Laws and regulations. And yet the worst of misdemeanors committed by the worst of all his favourites, in the hight of thir dominion, whether acts of rigor or remissness, he hath from time to time continu'd, own'd, and taken upon himself by public Declarations, as oft'n as the Clergy, or any other of his Instruments felt themselves over burd'n'd with the peoples hatred. And who knows not the superstitious rigor of his Sundays Chappel, and the licentious remissness of his Sundays Theater; accompanied with that reverend Statute for Dominical Jiggs and May-poles, publish'd in his own Name, and deriv'd from the example of his Father James. Which testifies all that rigor in superstition, all that remissness in Religion to have issu'd out originally from his own House, and from his own Autority. Much rather then may those general miscarriages in State, his proper Sphear, be imputed to no other person chiefly then to himself. And which of all [8] those oppressive Acts, or Impositions did he ever disclaim or disavow, till the fatal aw of this Parlament hung ominously over him. Yet heerh ee smoothly seeks to wipe off all the envie of his evill Goverment upon his Substitutes, and under Officers: and promises, though much too late, what wonders he purpos'd to have don in the reforming of Religion; a work wherein all his undertakings heretofore declare him to have had little or no judgement. Neither could his Breeding, or his cours of life acquaint him with a thing so Spiritual. Which may well assure us what kind of Reformation we could expect from him; either som politic form of an impos'd Religion, or els perpetual vexation, and persecution to all those that comply'd not with such a form. The like amendment hee promises in State; not a stepp furder then his Reason and Conscience told him was fitt to be desir'd; wishing hee had kept within those bounds, and not suffer'd his own judgement to have binover-borne in some things, of which things one was the Earl of Straffords execution. And what signifies all this, but that stil his resolution was the same, to set up an arbitrary Goverment of his own; and that all Britain was to be ty'd and chain'd to the conscience, judgement, and reason of one Man; as if those gifts had been only his peculiar and Prerogative, intal'd upon him with his fortune to be a King. When as doubtless no man so obstinate, or so much a Tyrant, but professes to be guided by that which he calls his Reason, and his Judgement, though never so corrupted; and pretends also his conscience. In the mean while, for any Parlament or the whole Nation to have either reason, judgement, [9] or conscience, by this rule was altogether in vaine, if it thwarted the Kings will; which was easie for him to call by any other more plausible name. He himself hath many times acknowledg'd to have no right over us but by Law; and by the same Law to govern us: but Law in a Free Nation hath bin ever public reason, the enacted reason of a Parlament; which he denying to enact, denies to govern us by that which ought to be our Law; interposing his own privat reason, which to us is no Law. And thus we find these faire and specious promises, made upon the experience of many hard sufferings, and his most mortifi'd retirements, being throughly sifted, to containe nothing in them much different from his former practices, so cross, and so averse to all his Parlaments, and both the Nations of this Iland. What fruits they could in likelyhood have produc'd in his restorement, is obvious to any prudent foresight.

And this is the substance of his first section, till wee come to the devout of it, model'd into the form of a privat Psalter. Which they who so much admire, either for the matter or the manner, may as well admire the Arch-Bishops late Breviary, and many other as good Manuals, and Handmaids of Devotion, the lip-work of every Prelatical Liturgist, clapt together, and quilted out of Scripture phrase, with as much ease, and as little need of Christian diligence, or judgement, as belongs to the compiling of any ord'nary and salable peece of English Divinity, that the Shops value. But he who from such a kind of Psalmistry, or any other verbal Devotion, without the pledge and earnest of sutable deeds, can be [10] perswaded of a zeale, and true righteousness in the person, hath much yet to learn; and knows not that the deepest policy of a Tyrant hath bin ever to counterfet Religious. And Aristotle in his Politics, hath mentiond that special craft among twelve other tyrannical Sophisms. Neither want wee examples. Andronicus Comnenus the Byzantine Emperor, though a most cruel Tyrant, is reported by Nicetas to have bin a constant reader of Saint Pauls Epistles; and by continual study had so incorporated the phrase & stile of that transcendent Apostle into all his familiar Letters, that the imitation seem'd to vie with the Original. Yet this availd not to deceave the people of that Empire; who not withstanding his Saints vizard, tore him to peeces for his Tyranny. From Stories of this nature both Ancient and Modern which abound, the Poets also, and som English, have bin in this point so mindfull of Decorum, as to put never more pious words in the mouth of any person, then of a Tyrant. I shall not instance an abstruse Author, wherein the King might be less conversant, but one whom wee well know was the Closet Companion of these his solitudes, William Shakespeare; who introduces the Person of Richard the third, speaking in as high a strain of pietie, and mortification, as is utterd in any passage of this Book; and sometimes to the same sense and purpose with some words in this place, I intended, saith he, not onely to oblige my Friends but mine enemies. The like saith Richard, Act. 2. Scen. 1,

I doe not know that Englishman alive.

With whom my soule is any jott at odds,

More then the Infant that is borne to night;

I thank my God for my humilitie.

[11]

Other stuff of this sort may be read throughout the whole Tragedie, wherein the Poet us'd not much licence in departing from the truth of History, which delivers him a deep dissembler, not of his affections onely, but of Religion.

In praying therfore, and in the outward work of Devotion, this King wee see hath not at all exceeded the worst of Kings before him. But herein the worst of Kings, professing Christianism, have by farr exceeded him. They, for ought we know, have still pray'd thir own, or at least borrow'd from fitt Authors. But this King, not content with that which, although in a thing holy, is no holy theft, to attribute to his own making other mens whole Prayers, hath as it were unhallow'd, and unchrist'nd the very duty of prayer it self, by borrowing to a Christian use Prayers offer'd to a Heathen God. Who would have imagin'd so little feare in him of the true allseeing Deitie, so little reverence of the Holy Ghost, whose office is to dictat and present our Christian Prayers, so little care of truth in his last words, or honour to himself, or to his Friends, or sense of his afflictions, or of that sad howr which was upon him, as immediatly before his death to popp into the hand of that grave Bishop who attended him, for a special Relique of his saintly exercises, a Prayer stol'n word for word from the mouth a of Heathen fiction praying to a heathen God; & that in no serious Book, but the vain amatorious Poem of Sr Philip Sidneys Arcadia; a Book in that kind full of worth and witt, but among religious thoughts, and duties not worthy to be nam'd; nor to be read at any time without good caution; much less in time of trouble and affliction to [12] be a Christians Prayer-Book. They who are yet incredulous of what I tell them for a truth, that this Philippic Prayer is no part of the Kings goods, may satisfie thir own eyes at leasure in the 3 d. Book of Sir Philips Arcadia p. 248. comparing Pammela's Prayer with the first Prayer of his Majestie, deliverd to Dr. Juxion immediatly before his death, and Entititl'd, A prayer in time of Captivity Printed in all the best Editions of his Book. And since there be a crew of lurking raylers, who in thir Libels, and thir fitts of rayling up and down, as I hear from others, take it so currishly that I should dare to tell abroad the secrets of thir Aegyhtian Apis, to gratify thir gall in som measure yet more, which to them will be a kinde of almes (for it is the weekly vomit of thir gall which to most of them is the sole meanes of thir feeding) that they may not starv for me, I shall gorge them once more with this digrsestion somwhat larger then before: nothing troubl'd or offended at the working upward of thir Sale-venom thereupon, though it happ'n to asperse me; beeing, it seemes, thir best livelyhood and the only use or good digestion that thir sick and perishing mindes can make of truth charitably told them. However, to the benesit of others much more worth the gaining, I shall proceed in my assertion; that if only but to tast wittingly of meat or drink offerd to an Idol, be in the doctrin of St. Paul judg'd a pollution, much more must be his sin who takes a prayer, so dedicated, into his mouth, and offers it to God. Yet hardly it can be thought upon (though how sad a thing) without som kindof laughter at the manner, and solemn transaction of so gross a cousenage: that he who had [13] trampl'd over us so stately and so tragically should leave the world at last so ridiculously in his exit, as to bequeath among his Deifying friends that stood about him such a pretious peece of mockery to be publisht by them, as must needs cover both his and their heads wth shame, if they have any left. Certainly they that will, may now see at length how much they were deceiv'd in him, and were ever like to be hereafter, who car'd not, so neer the minute of his death, to deceive his best and deerest freinds with the trumpery of such a prayer, not more secretly then shamefully purloind; yet giv'n them as the royall issue of his own proper Zeal. And sure it was the hand of God to let them fal & be tak'n in such a foolish trapp, as hath exposd them to all derision; if for nothing els, to throw contempt and disgrace in the sight of all men upon this his Idoliz'd Book, and the whole rosarie of his Prayers; thereby testifying how little he accepted them from those who thought no better of the living God then of a buzzard Idol, fitt to be so servd and worshipt in reversion, with the polluted orts and refuse of Arcadia's and Romances, without being able to discern the affront rather then the worship of such an ethnic Prayer. But leaving what might justly be offensive to God, it was a trespass also more then usual against human right, which commands that every Author should have the property of his own work reservd to him after death as well as living. Many Princes have bin rigorous in laying taxes on thir Subjects by the head, but of any King heertofore that made a levy upon thir witt, and seisd it as his own legitimat, I have not whom beside to instance. True it is I lookt [14] rather to have found him gleaning out of Books writt'n purposely to help Devotion. And if in likelyhood he have borrowd much more out of Prayer-books then out of Pastorals, then are these painted Feathers, that set him off so gay among the people, to be thought few or none of them his own. But if from his Divines he have borrow'd nothing, nothing out of all the Magazin, and the rheume of thir Mellifluous prayers and meditations, let them who now mourn for him as for Tamuz, them who howle in thir Pulpits, and by thir howling declare themselvs right Wolves, remember and consider in the midst of thir hideous faces, when they doe onely not cutt thir flesh for him like those ruefull Preists whom Eliah mock'd; that he who was once thir Ahab, now thir Josiah, though faining outwardly to reverence Churchmen, yet heer hath so extremely set at nought both them and thir praying faculty, that being at a loss himself what to pray in Captivity, he consulted neither with the Liturgie, nor with the Directory, but neglecting the huge fardell of all thir honycomb devotions, went directly where he doubted not to find better praying, to his mind with Pammela in the Countesses Arcadia. What greater argument of disgrace & ignominy could have bin thrown with cunning upon the whole Clergy, then that the King among all his Preistery, and all those numberles volumes of thir theological distillations, not meeting with one man or book of that coate that could befreind him with a prayer in Captivity, was forc'd to robb Sr. Philip and his Captive Shepherdess of thir Heathen orisons, to supply in any fashion his miserable indigence, not of bread, but of a single [15] prayer to God. I say therfore not of bread, for that want may befall a good man, and yet not make him totally miserable: but he who wants a prayer to beseech God in his necessity, tis unexpressible how poor he is; farr poorer within himself then all his enemies can make him. And the unfitness, the undecency of that pittifull supply which he sought, expresses yet furder the deepness of his poverty.

Thus much be said in generall to his prayers, and in special to that Arcadian prayer us'd in his Captivity, anough to undeceave us what esteeme wee are to set upon the rest. For he certainly whose mind could serve him to seek a Christian prayer out of a Pagan Legend, and assume it for his own, might gather up the rest God knows from whence; one perhaps out of the French Astraea, another out of the Spanish Diana; Amadis and Palmerin could hardly scape him. Such a person we may be sure had it not in him to make a prayer of his own, or at least would excuse himself the paines and cost of his invention, so long as such sweet rapsodies of Heathenism and Knighterrantry could yeild him prayers. How dishonourable then, and how unworthy of a Christian King were these ignoble shifts to seem holy and to get a Saintship among the ignorant and wretched people; to draw them by this deception, worse then all his former injuries, to go a whooring after him. And how unhappy, how forsook of grace, and unbelovd of God that people who resolv to know no more of piety or of goodnes, then to account him thir cheif Saint and Martyr, whose bankrupt devotion came not honestly by his very prayers; but having sharkd them from the mouth of a Heathen worshipper, [16] detestable to teach him prayers, sould them to those that stood and honourd him next to the Messiah, as his own heav'nly compositions in adversity, for hopes no less vain and presumptuous (and death at that time so imminent upon him) then by these goodly reliques to be held a Saint and Martyr in opinion with the People.

And thus farr in the whole Chapter we have seen and consider'd, and it cannot but be cleer to all men, how, and for what ends, what concernments, and necessities the late King was no way induc'd, but every way constrain'd to call this last Parlament: yet heer in his first prayer he trembles not to avouch as in the eares of God, That he did it with an upright intention, to his glory, and his peoples good: Of which dreadfull attestation how sincerely meant, God, to whom it was avow'd, can onely judge; and he hath judg'd already; and hath writt'n his impartial Sentence in Characters legible to all Christ'ndom; and besides hath taught us, that there be som, whom he hath giv'n over to delusion; whose very mind and conscience is defil'd; of whom Saint Paul to Titus makes mention.

II. Upon the Earle of Straffords Death.↩

THis next Chapter is a penitent confession of the King, and the strangest, if it be well weigh'd, that ever was Auricular. For hee repents heer of giving his consent, though most unwillingly, to the most seasonable and solemn peece of Justice, that had bin don of many yeares in the Land: But his [17] sole conscience thought the contrary. And thus was the welfare, the safety, and within a little, the unanimous demand of three populous Nations to have attended stil on the singularity of one mans opi nionated conscience; if men had bin always so tame and spiritless; and had not unexpectedly found the grace to understand, that if his conscience were so narrow and peculiar to it selfe, it was not fitt his Authority should be so ample and Universall over others. For certainly a privat conscience sorts not with a public Calling; but declares that Person rather meant by nature for a private fortune. And this also we may take for truth, that hee whose conscience thinks it sin to put to death a capital Offendor, will as oft think it meritorious to kill a righteous Person. But let us heare what the sin was that lay so sore upon him, and, as one of his Prayers giv'n to Dr. Juxton testifies, to the very day of his death; it was his signing the Bill of Straffords execution: a man whom all men look'd upon as one of the boldest and most impetuous instruments that the King had to advance any violent or illegal designe. He had rul'd Ireland, and som parts of England in an Arbitrary manner, had indeavour'd to subvert Fnndamental Lawes, to subvert Parlaments, and to incense the King against them; he had also endeavor'd▪ to make Hostility between England and Scotland: He had counceld the King to call over that Irish Army of Papists, which he had cunningly rais'd, to reduce England, as appear'd by good Testimony then present at the Consultation. For which, and many other crimes alledg'd and prov'd against him in 28, Articles, he was condemnd of high Treason by the [18] Parlament. The Commons by farr the greater number cast him; the Lords, after they had bin satisfi'd in a full discours by the Kings Sollicitor, and the opinions of many Judges deliver'd in thir House, agreed likewise to the Sentence of Treason. The People universally cri'd out for Justice. None were his Friends but Coutiers, and Clergimen, the worst at that time, and most corrupted sort of men; and Court Ladies, not the best of Women; who when they grow to that insolence as to appeare active in State affaires, are the certain sign of a dissolute, degenerat, and pusillanimous Common-wealth. Last of all the King, or rather first, for these were but his Apes, was not satisfi'd in conscience to condemn him of High Treason; and declar'd to both Houses, That no fears or respects whatsoever should make him alter that resolution founded upon his conscience. Either then his resolution was indeed not founded upon his conscience, or his conscience receav'd better imformation, or else both his conscience and this his strong resolution strook saile, notwithstanding these glorious words, to his stronger fear. For within a few dayes after, when the Judges at a privie Counsel, and four of his elected Bishops had pick'd the thorn out of his conscience, he was at length perswaded to signe the Bill for Straffords Execution. And yet perhaps that it wrung his conscience to condemn the Earle of high Treason is not unlikely: not because he thought him guiltless of highest Treason, had half those crimes bin committed against his own privat Interest or Person, as appear'd plainly by his charge against the six Members, but because he knew himself [19] a Principal in what the Earl was but his accessory, and thought nothing Treason against the Common-wealth, but against himself only.

Had he really scrupl'd to sentence that for Treason which he thought not Treasonable, why did he seeme resolv'd by the Judges and the Bishops? And ifby them resolv'd, how comes the scruple heer again? It was not then, as he now pretends, The importunities of some and the feare of many which made him signe, but the satisfaction giv'n him by those Judges & Ghostly Fathers of his own choosing. Which of him shall we believe? For hee seemes not one, but double; either heer we must not beleeve him professing that his satisfaction was but seemingly receav'd & out of feare, or els wee may as well beleeve that the scruple was no real scruple, as we can beleeve him heer against himself before, that the satisfaction then receiv'd was no real satisfaction: of such a variable and fleeting conscience what hold can be tak'n? But that indeed it was a facil conscience▪ and could dissemble satisfaction when it pleas'd, his own ensuing actions declar'd: being soon after found to have the chief hand in a most detested conspiracy against the Parlament and Kingdom, as by Letters and examinations of Percy, Goring, and other Conspirators came to light; that his intention was to rescue the Earle of Strafford, by seizing on the Towre of London; to bring up the English Army out of the North, joyn'd with eight thousand Irish Papists rais'd by Strafford, and a French Army to be landed at Portsmouth against the Parlament and thir Friends. For which purpose the King, though requested by both Houses to disband those Irish Papists, [20] refus'd to do it, and kept them still in Armes to his own purposes. No marvel then, if being as deeply criminous as the Earle himself, it stung his conscience to adjudge to death those misdeeds whereof himself had bin the chiefe Author: no marvel though in stead of blaming and detesting his ambition, his evil Counsel, his violence and oppression of the people, he fall to praise his great Abilities; and with Scolastic flourishes beneath the decencie of a King, compares him to the Sun, which in all figurative use, and significance beares allusion to a King, not to a Subject: No marvel though he knit contradictions as close as words can lye together, not approving in his judgement, and yet approving in his subsequent reason all that Strafford did, as driv'n by the necessity of times and the temper of that people; for this excuses all his misdemeanors: Lastly, no marvel that he goes on building many faire and pious conclusions upon false and wicked premises, which deceive the common Reader notwell discerning the antipathy of such connexions: but this is themarvel, & may be the astonishment of all that have a conscience, how he durst in the sight of God (and with the same words of contrition wherwith David repents the murdering of Uriah) repent his lawfull compliance to that just act of not saving him, whom he ought to have deliver'd up to speedy punishment; though himself the guiltier of the two. If the deed were so sinfull to have put to death so great a malefactor, it would have tak'n much doubtless from the heaviness of his sin, to have told God in his confession, how he labour'd, what dark plots he had contriv'd, into what a league enterd, and with what [21] Conspirators against his Parlament and Kingdoms, to have rescu'd from the claime of Justice so notable and so deare an Instrument of Tyranny: Which would have bin a story, no doubt as pleasing in the eares of Heav'n, as all these equivocal repentances. For it was feare, and nothing els, which made him faine before both the scruple and the satisfaction of hisconscience, that is to say, of his mind: his first feare pretended conscience that he might be born with to refuse signing; his latter feare being more urgent made him finde a conscience both to signe and to be satisfy'd. As for repentance it came not on him till a long time after; when he saw he could have sufferd nothing more, though he had deny'd that Bill. For how could he understandingly repent of letting that be Treason which the Parlament and whole Nation so judg'd? This was that which repented him, to have giv'n up to just punishment so stout a Champion of his designes, who might have bin so usefull to him in his following civil Broiles. It was a worldy repentance not a conscientious; or els it was a strange Tyranny which his conscience had got over him, to vex him like an evil spirit for doing one act of Justice, and by that means to fortifie his resolution from ever doing so any more. That mind must needs be irrecoverably deprav'd, which either by chance or importunity tasting but once of one just deed, spatters at it, and abhorrs the relish ever after. To the Scribes and Pharises, woe was denounc'd by our Saviour, for straining at a Gnatt and swallowing a Camel; though a Gnatt were to be straind at: But to a conscience with whom one good deed is so hard to pass down, as to endanger almost a choaking, and bad [22] deeds without number though as bigg and bulkie as the ruin of three Kingdoms, goe down currently without straining, certainly a farr greater woe appertaines. If his conscience were come to that unnatural dyscra sie, as to digest poyson and to keck at wholsom food, it was not for the Parlament, or any of his Kingdoms to feed with him any longer. Which to concele he would perswade us that the Parlament also in their conscience escap'd not some touches of remorse for putting Strafford to death, in forbidding it by an after act to be a precedent for the future. But in a fairer construction, that act imply'd rather a desire in them to pacifie the Kings mind, whom they perceav'd by this meanes quite alienated: in the mean while not imagining that this after act should be retorted on them to tie up Justice for the time to come upon like occasion, whether this were made a precedent or not, no more then the want of such a precedent, if it had bin wanting, had bin available to hinder this.

But how likely is it that this after act argu'd in the Parlament thir least repenting for the death of Strafford, when it argu'd so little in the King himself: who notwithstanding this after act which had his own hand and concurrence, if not his own instigation, within the same yeare accus'd of high Treason no less then six Members at once for the same pretended crimes which his conscience would not yeeld to think treasonable in the Earle. So that this his suttle Argument to fast'n a repenting, and by that means a guiltiness of Straffords death upon the Parlament, concludes upon his own head; and shews us plainly that either nothing in his judgment was [23] Treason against the Common-wealth, but onely against the Kings Person, a tyrannical Principle, or that his conscience was a perverse and prevaricating conscience, to scruple that the Common-wealth should punish for treasonous in one eminent offender, that wch he himself sought so vehemently to have punisht in six guiltless persons. If this were that touch of conscience which he bore with greater regrett, then for any sin committed in his life, whether it were that proditory Aid sent to Rochel and Religion abroad, or that prodigality of shedding blood at home, to a million of his Subjects lives not valu'd in comparison of one Strafford, we may consider yet at last, what true sense and feeling could be in that conscience, and what fitness to be the maister conscience of three Kingdoms.

But the reason why he labours that wee should take notice of so much tenderness and regrett in his soule for having any hand in Straffords death, is worth the marking ere we conclude. He hop'd it would be someevidence before God and Man to all posteritie that he was farr from bearing that vast load and guilt of blood layd upon him by others. Which hath the likeness of a suttle dissimulation; bewailing the blood of one man, his commodious Instrument, put to death most justly, though by him unwillingly, that we might think him too tender to shed willingly the blood of those thousands, whom he counted Rebels. And thus by dipping voluntarily his fingers end, yet with shew of great remorse in the blood of Strafford, wherof all men cleer him, he thinks to scape that Sea of innocent blood wherein his own guilt inevitably hath plung'd him all over. And we may well perceave [24] to what easie satisfactions and purgations he had inur'd his secret conscience, who thaught, by such weak policies and ostentations as these, to gaine beleif and absolution from understanding Men.

III. Upon his going to the House of Commons.↩

COncerning his unexcusable, and hostile march from the Court to the House of Commons, there needs not much be said. For he confesses it to be an act which most men, whom he calls his enemies cry'd shame upon; indifferent men grew jealous of and fearfull, and many of his Friends resented as a motion rising rather from passion then reason: He himself, in one of his Answers to both Houses, made profession to be convinc'd that it was a plaine breach of thir Privilege: Yet heer like a rott'n building newly trimm'd over he represents it speciously and fraudulently to impose upon the simple Reader; and seeks by smooth and supple words not heer only, but through his whole Book, to make som beneficial use or other ev'n of his worst miscarriages.

These Men, saith he, meaning his Friends, knew not the just motives and pregnant grounds with which I thought my selfe furnish'd; to wit, against the five Members, whom hee came to dragg out of the House. His best Friends indeed knew not, nor could ever know his motives to such a riotous act: and had he himself known any just grounds, he was not ignorant how [25] much it might have tended to his justifying, had he nam'd them in this place, and not conceal'd them. But suppose them real, suppose them known, what was this to that violation and dishonor put upon the whole House, whose very dore forcibly kept op'n, and all the passages neer it he besett with Swords and Pistols cockt and menac'd in the hands of about three hunderd Swaggerers and Ruffians, who but expected, nay audibly call'd for the word of onset to beginn a slaughter.

He had discover'd as he thought unlawfull correspondencies which they had vs'd, and ingagements to imbroile his Kingdomes, and remembers not his own unlawfull correspondencies, and conspiracies with the Irish Army of Papists, with the French to land at Portsmouth, and his tampering both with the English and the Scotch Army, to come up against the Parlament: the least of which attempts by whomsoever, was no less then manifest Treason against the Commonwealth.

If to demand Justice on the five Members were his Plea, for that which they with more reason might have demanded Justice upon him (I use his own Argument) there needed not so rough assistance. If hee had resolv'd to bear that repulse with patience, which his Queen by her words to him at his return little thought he would have done, wherfore did he provide against it, with such an armed and unusual force? But his heart serv'd him not to undergoe the hazzard that such a desperate scuffle would have brought him to. But wherfore did he goe at all, it behooving him to know there were two Statutes that declar'd he ought first to have acquainted the [26] Parlament, who were the Accusers, which he refus'd to doe, though still professing to govern by Law, and still justifying his attempts against Law. And when he saw it was not permitted him to attaint them but by a faire tryal, as was offerd him from time to time, for want of just matter which yet never came to light, he let the business fall of his own accord; and all those pregnancies, and just motives came to just nothing.

He had no temptation of displeasure or revenge against those men: None, but what he thirsted to execute upon them, for the constant opposition which they made against his tyrannous proceedings, and the love and reputation which they therfore had among the People, but most immediatly, for that they were suppos'd the chief by whose activity those 12. protesting Bishops were but a week before committed to the Tower.

He mist but little to have produc'd Writings under some mens own hands. But yet he mist, though thir Chambers, Trunks, and Studies were seal'd up and search'd; yet not found guilty. Providence would not have it so. Good Providence, that curbs the raging of proud Monarchs, as well as of madd multitudes. Yet he wanted not such probabilities (for his pregnant is come now to probable) as were sufficient to raise jealousies in any Kings heart. And thus his pregnant motives are at last prov'd nothing but a Tympany, or a Queen Maries Cushion: For in any Kings heart, as Kings goe now, what shadowie conceit, or groundless toy will not create a jealousie.

That he had design'd to assault the House of Commons, taking God to witness, he utterly denies; yet, in his [27] Answer to the City, maintaines that any course of violence had bin very justifiable. And we may then guess how farr it was from his designe. However it discover'd in him an excessive eagerness to be aveng'd on them that cross'd him; and that to have his will, he stood not to doe things never so much below him. What a becomming sight it was to see the King of England one while in the House of Commons, by and by in the Guild-Hall among the Liveries and Manufactures, prosecuting so greedily the track of five or six fled Subjects; himself not the Sollicitor onely, but the Pursivant and the Apparitor of his own partial cause. And although, in his Answers to the Parlament, hee hath confess'd, first that his manner of prosecution was illegal, next, that as hee once conceiv'd hec had ground anough to accuse them; so at length that hee found as good cause to desert any prosecution of them, yet heer he seems to reverse all, and against promise takes up his old deserted accusation, that he might have something to excuse himself, instead of giving due reparation; which he always refus'd to give them, whom he had so dishonor'd.

That I went, saith he of his going to the House of Commons, attended with some Gentlemen; Gentlemen indeed; the ragged Infantrie of Stewes and Brothels; the spawn and shiprack of Taverns and Dicing Houses: and then he pleads it was no unwonted thing for the Majesty and safety of a King to be so attended, especially in discontented times. An illustrious Majestie no doubt, so attended: a becomming safety for the King of England, plac'd in the fidelity of such Guards and Champions; Happy times; when Braves and Hacksters, the onely contented Members of his Goverment, [28] were thought the fittest and the faithfullest to defend his Person against the discontents of a Parlament and all good Men. Were those the chos'n ones to preserve reverence to him, while he enterd unassur'd, and full of suspicions into his great and faithfull Councel? Let God then and the World judge whether the cause were not in his own guilty and unwarrantable doings: The House of Commons upon several examinations of this business declar'd it sufficiently prov'd, that the comming of those soldiers, Papists and others with the King, was to take away some of thir Members, and in case of opposition or denyal, to have fal'n upon the House in a hostile manner, This the King heer denies; adding a fearful imprecation against his own life, If he purposed any violence or oppression against the Innocent, then, saith he, let the Enemie persecute my soule, and tred my life to the ground and lay my honor in the dust. What need then more disputing? He appeal'd to Gods Tribunal, and behold God hath judg'd, and don to him in the sight of all men according to the verdict of his own mouth. To be a warning to all Kings hereafter how they use presumptuously the words and protestations of David, without the spirit and conscience of David. And the Kings admirers may heer see thir madness to mistake this Book for a monument of his worth and wisdom, when as indeed it is his Doomsday Booke; not like that of William the Norman his Predecessor, but the record and memorial of his condemnation: and discovers whatever hath befal'n him, to have bin hast'nd on from Divine Justice by the rash and inconsiderat appeal of his own lipps. But what evasions, what pretences, though never so unjust [29] and emptie, will he refuse in matters more unknown, and more involv'd in the mists and intricacies of State, who, rather then not justifie himself in a thing so generally odious, can flatter his integritie with such frivolous excuses against the manifest dissent of all men, whether Enemies, Neuters, or Friends. But God and his judgements have not bin mock'd; and good men may well perceive what a distance there was ever like to be between him and his Parlament, and perhaps between him and all amendment, who for one good deed, though but consented to, askes God forgiveness; and from his worst deeds don, takes occasion to insist upon his rightecusness.

IV. Vpon the Insolency of the Tumults.↩

WEE have heer, I must confess, a neat and wellcouch'd invective against Tumults; expressing a true feare of them in the Author, but yet so handsomly compos'd, and withall so feelingly, that, to make a Royal comparison, I beleeve Rehoboam the Son of Solomon could not have compos'd it better. Yet Rehoboam had more cause to inveigh against them; for they had ston'd his Tribute-gatherer, and perhaps had as little spar'd his own Person, had hee not with all speed betak'n him to his Charret. But this King hath stood the worst of them in his own House without danger, when his Coach and Horses, in a Panic fear, have bin to seek, which argues that the Tumults at Whitehall were nothing so dangerous as those at Sechem.

[30]

But the matter heer considerable, is not whether the King, or his Houshold Rhetorician have made a pithy declamation against Tumults, but first whether these were Tumults or not, next if they were, whether the King himself did not cause them. Let us examin therfore how things at that time stood. The King, as before hath bin prov'd, having both call'd this Parlament unwillingly, and as unwillingly from time to time condescended to thir several acts, carrying on a disjoynt and privat interest of his own, and not enduring to be so cross'd and overswaid, especially in the executing of his chief & bold est Instrument, the Deputy of Ireland, first tempts the English Army, with no less reward then the spoil of London, to come up, and destroy the Parlament. That being discover'd by some of the Officers, who, though bad anough, yet abhorr'd so foul a deed, the K. hard'nd in his purpose, tempts them the 2d time at Burrow Bridge, promises to pawn his Jewels for them, & that they should be mett & assisted (would they but march on) wth a gross body of hors under the E. of Newcastle. He tempts them yet the third time, though after discovery, & his own abjuration to have ever tempted them, as is affirmd in the Declaration of no more addresses. Neither this succeeding, he turnes him next to the Scotch Army; & by his own credential Letters giv'n to Oneal and Sr John Hinderson, baites his temptation with a richer reward; not only to have the sacking of London, but four Northern Counties to be made Scottish; wth Jewels of great value to be giv'n in pawn thewhile. But neither would the Scots, for any promise of reward, be bought to such an execrable and odious treachery; but with much honesty gave notice [31] of the Kings designe, both to the Parlament and City of London. The Parlament moreover had intelligence, and the people could not but discern, that there was a bitter & malignant party grown up now to such a boldness, as to give out insolent and threatning speeches against the Parlament it self. Besides this, the Rebellion in Ireland was now broke out; and a conspiracy in Scotland had bin made, while the King was there, against some chief Members of that Parlament; great numbers heer of unknown, and suspicious persons resorted to the City; the King being return'd from Scotland presently dismisses that Guard which the Parlament thought necessary in the midst of so many dangers to have about them; and puts another Guard in thir place, contrary to the Privilege of that high Court, and by such a one commanded, as made them no less doubtfull of the Guard it self. Which they therfore, upon som ill effects thereof first found, discharge; deeming it more safe to sitt free, though without a Guard in op'n danger, then inclos'd with a suspected safety. The people therfore, lest thir worthiest and most faithfull Patriots, who had expos'd themselves for the public, and whom they saw now left naked, should want aide, or be deserted in the midst of these dangers, came in multitudes, though unarm'd, to witness thir fidelitie and readiness in case of any violence offer'd to the Parlament. The King both envying to see the Peoples love thus devolv'd on another object, and doubting lest it might utterly disable him to doe with Parlaments as he was wont, sent a message into the City forbidding such resorts. The Parlament also both by what was discover'd to [32] them, and what they saw in a Malignant Party (some of which had already drawn blood in a Fray or two at the Court Gate, and eev'n at thir own Gate, in Westminster Hall) conceaving themselves to be still in danger where they sat, sent a most reasonable and just Petition to the King, that a Guard might be allow'd them out of the City, wherof the Kings own Chamberlaine, the Earl of Essex might have command; it being the right of inferiour Courts to make chois of thir own Guard. This the King refus'd to doe, and why he refus'd, the very next day made manifest. For on that day it was, that he sallied out from White Hall, with those trusty Myrmidons, to block up, or give assault to the House of Commons. He had, besides all this, begun to fortifie his Court, and entertaind armed Men not a few; who standing at his Palace Gate, revil'd, and with drawn Swords wounded many of the People, as they went by unarm'd, and in a peaceable manner, whereof some dy'd. The passing by of a multitude, though neither to Saint Georges Feast, nor to a Tilting, certainly of it self was no Tumult; the expression of thir Loyalty and stedfastness to the Parlament, whose lives and safeties by more then slight rumours they doubted to be in danger, was no Tumult. If it grew to be so, the cause was in the King himself and his injurious retinue, who both by Hostile preparations in the Court, and by actual assailing of the People, gave them just cause to defend themselves.

Surely those unarmed and Petitioning People needed not have bin so formidable to any, but to such whose consciences misgave them how ill they had deserv'd of the People; and first began to injure [33] them, because they justly fear'd it from them; and then ascribe that to popular Tumult which was occasion'd by thir own provoking.

And that the King was so emphatical and elaborat on this Theam against Tumults, and express'd with such a vehemence his hatred of them, will redound less perhaps, then he was aware, to the commendation of his Goverment. For besides that in good Goverments they happ'n seldomèst, and rise not without cause, if they prove extreme and pernicious, they were never counted so to Monarchy, but to Monarchical Tyranny; and extremes one with another are at most Antipathy. If then the King so extremely stood in fear of Tumults, the inference will endanger him to be the other extreme. Thus farr the occasion of this discours against Tumults; now to the discours it self, voluble anough, and full of sentence, but that, for the most part, either specious rather then solid, or to his cause nothing pertinent.

He never thought any thing more to presage the mischiefes that ensu'd, then those Tumults. Then was his foresight but short, and much mistak'n. Those Tumults were but the milde effects of an evil and injurious raigne; not signes of mischeifs to come, but seeking releef for mischeifs past; those signes were to be read more apparent in his rage and purpos'd revenge of those free expostulations, and clamours of the People against his lawless Goverment. Not any thing, saith he, portends more Gods displeasure against a Nation then when he suffers the clamours of the Vulgar to pass all bounds of Law & reverence to Authority. It portends rather his dispeasure against a Tyrannous King, whose proud Throne he [34] intends to overturn by that contemptible Vulgar; the sad cries and oppressions of whom his Royaltie regarded not. As for that supplicating People they did no hurt either to Law or Autority, but stood for it rather in the Parlament against whom they fear'd would violate it.

That they invaded the Honour and Freedome of the two Houses, is his own officious accusation, not seconded by the Parlament, who had they seen cause, were themselves best able to complain. And if they shook & menac'd any, they were such as had more relation to the Court, then to the Common wealth; enemies, not patrons of the People. But if thir petitioning unarm'd were an invasion of both Houses, what was his entrance into the House of Commons, besetting it with armed men, in what condition then was the honour, and freedom of that House?

They forbore not rude deportments, contemptuous words and actions to himself and his Court.

It was more wonder, having heard what treacherous hostility he had design'd against the City, and his whole Kingdome, that they forbore to handle him as people in thir rage have handl'd Tyrants heertofore for less offences.

They were not a short ague, but a fierce quotidian feaver: He indeed may best say it, who most felt it; for the shaking was within him; and it shook him by his own description worse then a storme, worse then an earthquake, Belshazzars Palsie. Had not worse feares, terrors, and envies made within him that commotion, how could a multitude of his Subjects, arm'd with no other weapon then Petitions, have shak'n all his joynts with such a terrible ague. Yet that the Parlament [35] should entertaine the least feare of bad intentions from him or his Party, he endures not; but would perswade us that men scare themselves and others without cause; for he thought feare would be to them a kind of armor, and his designe was, if it were possible, to disarme all, especially of a wise feare and suspicion; for that he knew would find weapons.

He goes on therfore with vehemence to repeat the mischeifs don by these Tumults. They first Petition'd, then protected, dictate next, and lastly overaw the Parlament. They remov'd obstructions, they purg'd the Houses, cast out rott'n members. If there were a man of iron, such as Talus, by our Poet Spencer, is fain'd to be the page of Justice, who with his iron flaile could doe all this, and expeditiously, without those deceitfull formes and circumstances of Law, worse then ceremonies in Religion; I say God send it don, whether by one Talus, or by a thousand.

But they subdu'd the men of conscience in Parlament, back'd and abetted all seditious and schismatical Proposals against government ecclesiastical and civil.