SAMUEL RUTHERFORD,

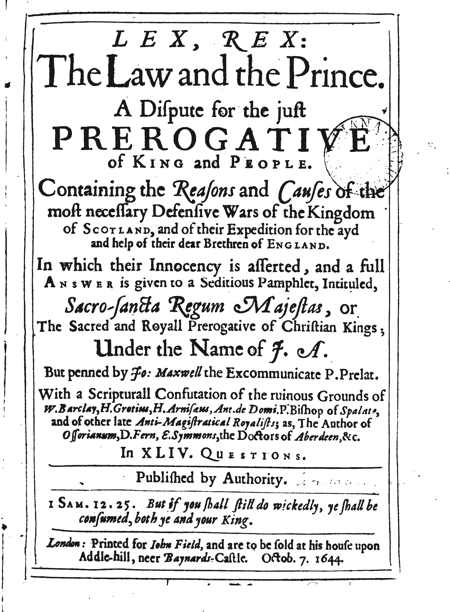

Lex, Rex: The Law and the Prince.

A Dispute for the just Prerogative of King and People (1644)

[Created: 30 October, 2024]

[Updated: 29 March, 2025] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, Lex, Rex: The Law and the Prince. A Dispute for the just Prerogative of King and People : containing the reasons and causes of the most necessary defensive wars of the kingdom of Scotland and of their expedition for the ayd and help of their dear brethren of England. (London: Printed for Iohn Field, Octob. 7, 1644).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1644-Rutherford_LexRex/Rutherford_LexRex1644-ebook.html

Samuel Rutherford, Lex, Rex: The Law and the Prince. A Dispute for the just Prerogative of King and People : containing the reasons and causes of the most necessary defensive wars of the kingdom of Scotland and of their expedition for the ayd and help of their dear brethren of England : in which their innocency is asserted and a full answer is given to a seditious pamphlet intituled Sacro-sancta regum majestas, or, The sacred and royall prerogative of Christian kings, under the name of J. A. but penned by Jo. Maxwell the excommunicate P. Prelat. : with a scripturall confutation of the ruinous grounds of W. Barclay, H. Grotius, H. Arnisœus, Ant. de Domi P. Bishop of Spalata, and of other late anti-magistratical royalists, as the author of Ossorianum, D. Fern, E. Symmons, the doctors of Aberdeen, &c. : in XLIV questions. (London: Printed for Iohn Field, Octob. 7, 1644).

1 SAM. 12.25. But if you shall still do wickedly, ye shall be consumed, both ye and your King.

Editor's Note: Because of the poor quality of the PDF of the original text there are many errors such as unreadable letters and words. The original editors also made no effort to transcribe or code the Greek and Hebrew words. The text did, however, include the page numbers. They also did not distinguish between marginal notes and footnotes, coding everything as endnotes. We have continued this practice.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

The Table of the Contents of the Book.

L. An. Senecae Octavia. Nero, Seneca

QUEST. I. WHether Government be by a divine Law?

- Affirmed, Pag. 1.

- How Government is from God, Ibid.

- Civill Power in the Root, immediately from God, Pag. 2,

QUEST. II. Whether or no Goverment be warranted by the Law of nature?

- Affirmed, Ibid.

- Civil societie naturall in radice, in the root, voluntary, in modo, in the manner, Ibid.

- Power of Government, and Power of Government, by such and such Magistrates, different, Pag. 2, 3.

- Civil subjection not formally from natures Law, Pag. 3.

- Our consent to Laws penal, not antecedently naturall, Ibid.

- Government by such Rulers, a secondary Law of nature, Ibid.

- Family Government and politike, different, Ibid.

- Government by Rulers, a secondary Law of nature; Family Government, and Civil, different, Pag. 4.

- Civil Government by consequent, naturall, Pag. 5.

QUEST. III. Whether Royall Power, and definite Forms of Government be from God?

- Affirmed, Ibid.

- That Kings are from God, understood in a fourfold sense, Pag. 5, 6.

- The Royall Power hath warrant from divine institution, Pag. 6.

- The three forms of Government, not different in spece and nature, P. 8.

- How every form is from God, Ibid.

- How Government is an ordinance of man, 1 Pet. 2.13. Pag. 8, 9.

- How the King is from God, how from the people, Ibid.

- Royall Power three wayes in the people, P. 6, 10.

- How Royall Power is radically in the people, P. 7.

- The people mak••th the King, Ibid.

- How any form of Government is from God, P. 8.

- How Government is a humane ordinance, 1 Pet. 2.3. P. 8, 9.

- The people creat the King, P. 10, 11.

- Making a King, and choosing a King, not to be distinguished, P. 12▪ 13.

- David not a King formally, because anointed by God, P. 14, 15.

- Kings made by the people, though the Office, in abstracto, were immediately from God, P. 16.

- The people have a reall action, more then approbation in making a King, P. 19,

- Kinging of a person ascribed to the people, P. 20.

- Kings in a speciall manner, are from God, but it followeth not: Ergo, not from the people, P. 21.

- The place, Prov. 8.15. proveth not, but Kings are made by the people. P. 22, 23.

- Nebuchadnezzar and other heathen Kings, had no just Title before God, to the Kingdom of Judah, and divers other subdued Kingdoms, P. 26, 27.

- The Forms of Government, not from God by an act of naked Providence, but by his approving will, Ibid.

- Soveraignty not from the people by sole approbation, P. 29, 30.

- Though God have peculiar acts of providence in creating Kings, it followeth not hence, that the people maketh not Kings, P. 31.

- The P. Prelate, exponeth prophecies true onely of David, Solomon, and Iesus Christ, as true of prophane heathen Kings, P. 34, 35.

- The P. P. maketh all the heathen Kings to be Princes, anointed with the holy Oyl of saving grace, Ibid.

QUEST. VII. Whether the P. Prelate conclude, that neither constitution, nor designation of Kings is from the people? Negatur, P. 38, 39.

- The excellency of Kings, maketh them not of Gods onely Constitution and Designation, Ibid.

- How Soveraigntie is in the people, how not, P. 43.

- A Communitie doth not surrender their right and libertie to their Rulers; so much as their power active, to do, and passive, to suffer violence, P. 44, 45.

- Gods loosing of the bonds of Kings, by the mediation of the peoples despising him, proveth against the P. P. That the Lord taketh away, and giveth Royall Majestie mediately, not immediately, P. 45, 46.

- The subordination of people to Kings and Rulers, both naturall and voluntary; the subordination of beasts and creatures to man meerly naturall, P. 46, 47.

- The place, Gen. 9.5. He that shedeth man's blood, &c. discussed, P. 47, 48.

QUEST. VIII. Whether or no, the P. Prelate proveth, by force of reason, That the people cannot be capable of any power of Goverment? Negatur, pag. 49, 50.

- In any communitie there is an active and passive power to Government, P. 50.

- Popular Government is not that wherein all the whole people are Governours, P. 53, 54.

- People by nature are equally indifferent to all the three Governments, and are under not any one by nature, P. 53.

- The P. Prelate, denyeth the Pope his father to be the Antichrist, Ibid.

- The bad successe of Kings chosen by people, proveth nothing against us, because Kings chosen by God, had bad successe through their own wickednesse, P. 54, 55.

- The P. Prelate condemneth King Charls his ratifying, Parl. 2. An. 1641. The whole proceedings of Scotland in this present Reformation, P. 56.

- That there be any supreme Judges, is an eminent act of divine providence, which hindereth not, but that the King is made by the people, P. 57.

- The people not patients in making a King, as is water in the Sacrament of Baptisme, in the Act of production of grace, P. 58.

QUEST. IX. Whether or no, Soveraigntie is so in and from the people, that they may resume their power in time of extreme necessity? Negatur. pag. 58.

- How the people is the subject of Soveraignty, Ibid.

- No Tyrannicall power is from God, P. 59.

- People cannot alienate the naturall power of self-defence, Ibid.

- The power of Parliaments, P. 60.

- The Parliament hath more power then the King, Ibid.

- Judges and Kings differ, P. 61.

- People may resume their power, not because they are infallible, but because they cannot so readily destroy themselves, as one man may do, P. 63.

- That the San••drim punished not David, Bathsheba, Joab, is but a fact, not a law, P. 63, 64.

- There is a subordination of Creatures naturall, Government must be naturall; and yet this, or that form, is voluntary, P. 65, 66, 67.

QUEST. X. Whether or not Royall birth be equivalent to Divine Unction? Negatur. pag. 68.

- Impugned by eight Arguments. Ibid.

- Royalty not transmitted from father to sonne. ibid.

- A family may be chosen to a Crown as a single person is chosen, but the tye is conditionall in both. pag. 68.69.

- The Throne by speciall promise made to David and his seed, by God,

- Psal. 89. no ground to make birth, In foro Dei, a just title to the crowne. pag. 69 70.

- A Title by conquest to a Throne must be unlawfull, if birth be Gods lawfull title. pag. 70.

- Royalists who held conqu••st to be a just title to the Crown, teach manifest treason against King Charles, and his Royall Heires. ibid.

- Only, Bona fortunae, not honour or Royalty properly transmittable from father to sonne. pag. 71.

- Violent conquest cannot regulate the consciences of people, to submit to a conquerour as their lawfull King. pag. 72.

- Naked birth is inferiour to that very divine unction, that made no man a King without the peoples election. pag. 73.

- If a Kingdome were by birth the King might sell it. pag. 74.

- The Crown is the Patrimony of the Kingdome, not of him who is King, or of his father pag. 72, 73, 76.

- Birth a typicall designement to the Crowne in Israel. pag. 74.

- The choise of a family to the Crowne resolveth upon the free election of the people, as on the fountaine-cause. pag. 76.

- Election of a family to the Crown lawfull. pag. 77.

QUEST. XI. Whether or no, he be more principally a King, who is a King by birth, or he who is a King by the free election of the people? Affir. posterius, pag. 79.

- The Elective King commeth nearer to the first King. Deut. 17. pag. 80.

- If the people may limit the King, they give him the power. ibid.

- A Community have not power formally to punish themselves. pag. 81.

- The Hereditary and the elective Prince in divers considerations better, or worse, each one then another. pag. 82.

QUEST. XII. Whether or no a Kingdome may lawfully be purchased by the sole Title of Conquest. Negatur. pag. 82.

- 7. Argu. for the nega••▪ a twofold right of conquest. ibid.

- Conquest turned in an after-consent of the people, becommeth a just title. pag. 83.

- Conquest not a signification to us of Gods approving will. pag. 84.

- Meere violent domineering contrary to the acts of governing. ibid.

- Violence hath nothing in it of a King. ibid.

- A bloody Conquerour not a blessing, per se, as a King is, pag. 85.

- Strength as prevailing is not Law or reason. pag. 86

- Fathers cannot dispone of the liberty of posterity not borne. ibid.

- A father as a father hath not power of life and death. pag. 87.

- Israels and Davids Conquests of the Canaanites, Edomites, Ammonites not lawfull, because conquest, but upon a Divine title of Gods promise. pag. 88.89.

- Seven sorts of superiority and inferiority. pag. 89, 90.

- Power of life and death from a positive Law. ibid.

- A Dominion antecedent and consequent. 90.

- Kings and subjects no naturall order. ibid.

- A man is borne, consequenter, in politick relation. pag. 91.

- Slavery not naturall from four reasons. ibid.

- Every man borne free in regard of civill subjection (not in regard of naturall, such as of children, and wife to Parents and Husband) proved by seven Arguments. pag. 91, 92, 93.

- Politique Government how necessary, how naturall. pag. 94.

- That Parents should inslave their children, not naturall. pag. 95.

- The King under a naturall, but no civill obligation to the people, as Royalists teach. ibid.

- The Covenant civilly tyeth the King, proved by Scriptures and reasons, by 8. Argu. ibid. & sequent.

- Jf the condition without which one of the parties would never have entered in Covenant, be not performed, that party is loosed from the Covenant. pag. 97.

- The people and Princes are obliged in their places for Iustice and Religion, no lesse then the King. pag. 98.

- In so farre as the King presseth a false Religion on the people, eatenus, in so farre they are understood not to have a King. pag. 99.

- The Covenant giveth a mutuall coactive power to King and people, to compell each other, though there be not one in earth higher then both to compell each of them. pag. 100.

- The Covenant bindeth the King as King, not as he is a man onely. pag. 101.

- One or two Tyrannous acts deprive not the King of his Royall right. pag. 104.

- Though there were no positive written Covenant (which yet we grant not) yet there is a naturall, tacit, implicit Covenant tying the King, by the nature of his Office. pag. 106

- If the King be made King absolutely, it is contrary to Scripture, and the nature of his Office. pag. 107.

- The people given to the King as a pledge, not as if they became his owne to dispose of at his absolute will. pag. 108.

- The King could not buy, sell, borrow, if no Covenant should tye him to men. ibid.

- The Covenant sworne by Iudah, 2 Chro. 15. tyed the King. pag. 109.

QUEST. XV. Whether the King be univocally or only Analogically and by proportion a father, pag. 111

- Adam not King of the whole earth, because a father. ibid.

- The King a Father Metaphorically and improperly, proved by eight Arguments. ibid. & sequent.

QUEST XVI. Whether or no a despoticall or masterly dominion agree to the King, because he is King. Negatur. pag. 116

- The King hath no masterly dominion over the Subjects, as if they were his servants. Proved by 4. Arguments. pag. 116.

- The King not over men as reasonable creatures to domineere. pag. 117.

- The King cannot give away his Kingdome or his people, as if they were his proper goods. ibid.

- A violent surrender of liberty tyeth not. pag. 119

- A surrender of ignorance is in so farre, unvoluntary, as it oblige not. ibid.

- The goods of the subjects not the Kings, proved by 8. Argu. pag. 120.

- All the goods of the subjects are the Kings in a four-fold sence· pag. 121·

- Affirmed, p. 124.

- The King a Tutor rather then a Father, as these are distinguished, ibid.

- A free Communitie not properly, and in all respects, a minor and pupill, p. 125.

- The Kings power not properly maritall and husbandly. ibid.

- The King a Patron, and Servant. pag. 126.

- The Royall power only from God, Immediatione simplicis constitutionis, & solum solitudine causae primae, but not Immediatione applicationis dignitatis ad personam. pag. 126.

- The King the Servant of the people both objectively, and subjectively. pag. 127.

- The Lord and the people by one and the same act according to the Physicall relation maketh the King. ibid.

- The King head of the people Metaphorically only, not essentially, not univocally by 6. Argu. pag. 128.

- His power fiduciary only. pag. 129.

QUEST. XVIII. What is the Law or manner of the King, 1 Sam. 8, 9, 11. the place discussed fully. pag. 130.

- The Power and the Office badly differenced by Barclay. pag. 130.

- What is 〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉 the manner of the King, by the harmony of Interpretors ancient and moderne, Protestants and Papists. pag. 131, 132, 133.

- Crying out, 1 Sam. 8. not necessarily a remedy of tyranny, nor a praying with faith and patience, pag. 135, 136.

- Resisting of Kings that are tyrannous and patience not inconsistent. ibid.

- The Law of the King not a permissive Law, as was the Law of Devorcement. pag. 136, 137.

- The Law of the King, 1 Sam. 12.23, 24. not a Law of tyranny, pag. 138, 139.

QUEST. XIX. Whether or no the King be in Dignity and Power above the people? Neg. Impugned by 10. Argu. p. 139.

- In what consideration the King is above the people, and the people above the King. pag. 139, 140.

- A meane as a meane inferiour to the end, how its true. ibid.

- The King inferiour to the people. ibid.

- The Church because the Church is of more excellency then the King, because King. pag. 140, 141.

- The people being those to whom the King is given, worthier then the gift. pag. 141.

- And the people immortall, the King mortall. pag. 142.

- The King a meane only, not both the efficient or Author of the Kingdome and a meane. Two necessary distinctions of a meane. pag. 143,

- If sin had never been there should have been no King. pag. 142.

- The King is to give his life for his people. ibid.

- The consistent cause more excellent then the effect. pag. 143, 144, 145.

- The people then the King. pag. 144, 145.

- Vnpossible people can limit Royall Power, but they must give Royall Power also. ibid.

- The people have an action in making a King, proved by foure Arguments. ibid.

- Though it were granted that God immediately made Kings, yet it is no consequent God only, and not the people, can unmake him. pag. 146.

- The people appointing a King over themselves, retaine the Fountaine-power of making a King. pag. 147, 148, 149.

- The meane inferiour to the end, and the King as King is a meane. pag. 149, 150, 153.

- The King as a meane, and also as a man inferiour to the people, pag. 150.

- To sweare non-selfe-preservation, and to sweare selfe-murther, all one. pag. 151.

- The people cannot make away their power. 1. Their whole power, nor 2. irrevocably to the King. pag. 152.

- The people may resume the power they give to the Commissioners of Parliament, when it is abused, p. 152,

- The Tables in Scotland lawfull, when the ordinary judicaturies are corrupt, p. 153.

- Quod efficit tale id ipsum magis tale, discussed, the fountain-power in the people, the derived onely in the King, p. 153, 154, 155.

- The King is a fiduciary, a life-renter, not a lord or heritor, p. 155, 156.

- How soveraigntie is in the people, p. 156, 157.

- Power of life and death, how in a Community, ibid.

- A Communitie voide of Rulers, is yet, and may be a politike body, p. 157.

- Iudges gods Analogically, p. 158.

- Inferiour Iudges the immediate Vicars of God, no lesse then the King, ibid.

- The consciences of inferiour Iudges, immediately subordinate to God, not to the King, either mediately or immediately, p. 160.

- How the inferiour Iudge is the deputy of the King? p. 161, 162.

- He may put to death murtherers, as having Gods sword committed to him, no lesse then the King, even though the King command the contrary; for he is not to execute judgement, and to relieve the oppressed, conditionally, if a mortall King give him leave; but whether the King will or no, he is to obey the King of Kings, p. 160, 161.

- Inferiour Iudges are ministri regni, non ministri regis, p. 162, 163.

- The King doth not make Iudges as he is a man, by an act of private good will; but as he is a King, by an act of Royall Iustice, and by a power that he hath from the people, who made himself supreme Iudge, p. 163, 164, 165.

- The Kings making of inferiour Iudges hindereth not, but they are as essentially Iudges as the King, who maketh them, not by fountain-power, but by power borrowed from the people, p. 165, 166.

- The Iudges in Israel, and the Kings, differ not essentially, p. 167.

- Aristocracy as naturall as Monarchie, and as warrantable, p. 168, 169.

- Inferiour Iudges depend some way on the King, in fieri, but not, in facto esse, p. 169, 170.

- The Parliament not Iudges by derivation from the King, p. 170.

- The King cannot make, nor unmake Iudges, ibid.

- No heritable Iudges, ibid.

- Inferiour Iudges more necessary then a King, p. 171, 172.

QUEST. XXI. What power the People, and States of Parliament, hath over the King, and in the State? p. 172.

- The Elders appointed by God, to be Iudges, p. 173.

- Parliaments may conveen, and judge without the King, p. 173, 174.

- Parliaments are essentially Iudges, and so their consciences neither dependeth on the King, quoad specificationem, that is, That they should give out this sentence, not this, nec quoad exercitium, That they should not in the morning execute judgement, p. 174, 175.

- Vnjust judging, and no judging at all, are sins in the States, p. 175.

- The Parliament coordinate Iudges with the King, not advisers onely, By eleven Arguments. p. 176, 177,

- Inferior Iudges not the Kings Messengers or Legates, but publike Governours, p. 176.

- The Jews Monarchie mixt, p. 178.

- A Power executive of Laws more in the King, a Power legislative more in the Parliament, p. 178, 179.

QUEST. XXII. Whether the power of the King as King, be absolute, or dependent, and limited by Gods first mould and patern of a King? Negatur, Prius, Affirmatur, Posterius, p. 179.

- The Royalists make the King as absolute as the Great Turk, p. 180.

- The King not absolute in his power, proved by nine Arguments, p. 181.182, 183, seq.

- Why the King is a living Law, p. 184.

- Power to do ill, not from God, ibid.

- Royalists say, power to do ill is not from God, but power to do ill as punishable by man, is from God, p. 186.

- A King, actu primo, is a plague, and the people slaves, if the King by Gods institution be absolute, p. 187.

- Absolutenesse of Royaltie against Iustice, Peace, Reason, Law, p. 189.

- Against the Kings relation of a brother, p. 190.

- A Damsel forced, may resist the King, ibid.

- The goodnesse of an absolute Prince hindereth not, but he is, actu primo, a Tyrant, p. 189.

QUEST. XXIII. Whether the King hath a Prerogative Royall above Laws? Negatur, p. 192.

- Prerogative taken two wayes, ibid.

- Prerogative above Laws, a Garland proper to infinite Majestie, ibid.

- A threefold dispensation, 1. Of power, 2. Of justice, 3. Of Grace, p. 194.

- Acts of meer grace, may be acts of blood, p. 195.

- An oath to the King of Babylon, tyed not the people of Judah to all that absolute power could command, ibid.

- The absolute Prince, is as absolute in acts of crueltie, as in acts of grace, p. 196.

- Servants are not, 1 Pet. 2.18, 19. interdited of self-defence, p. 199, 200.

- The Parliament materially onely, not formally, hath the King for their Lord, p. 202.

- Reason not a sufficient restraint to keep a Prince from Acts of tyranny, ibid.

- Princes have sufficient power to do good, though they have not absolute to do evil. p. 203.

- A power to shed innocent blood, can be no part of any Royall power given of God, p. 204.

- The King, because he is a publike person, wanteth many priviledges that subjects have, p. 205, 206.

QUEST. XXIV. What relation the King hath to the Law? p. 207.

- Humane Laws considered as reasonable, or as penal, ibid.

- The King alone hath not a Nemothetick power, p. 208.

- Whether the King be above Parliaments, as their Iudge? p. 208, p. 209, 210, 211.

- Subordination of the King to the Parliament, and coordination both consistent, p. 210, 211.

- Each one of the three Governments hath somewhat from each other, and they cannot any one of them, be in its prevalency, conveniently without the mixture of the other two, p. 211, 212.

- The King as a King cannot erre, as he erreth in so far, he is not the remedie of oppression and Anarchie, intended by God and nature, p. 212.

- In the court of necessitie, the people may judge the King, p. 213.

- Humane Laws not so obscure as tyranny is visible and discernable, p. 213, 214.

- Its more requisite, that the whole people, Church, and Religion, be secured, then one man, p. 215.

- If there be any restraint by Law on the King, it must be physicall; for a morall restraint is upon all men, p. 214, 215.

- To swear to an absolute Prince as absolute, is an oath eatenus, in so far unlawfull, and not obligatory, p. 215.

QUEST. XXV. Whether the supreme Law, the safetie of the people, be above the King? Affirmed, p. 218.

- The safetie of the people to be preferred to the King, for the King is no•• to seek himself, but the good of the people, p. 218, 219.

- Royalists make no Kings, but Tyrants, p. 222.

- How the safetie of the King is the safetie of the people, p. 223.

- A King for the safetie of the people, may break through the Letter and paper of a Law, p. 227.

- The Kings prerogative above Law and Reason, not comparable to the blood that has been shed in Ireland and England, p. 225, 226, 228.

- The power of Dictators prove not a Prerogative above Law, p. 229, 230.

QUEST. XXVI. Whether the King be above the Law? p. 230, 231.

- The Law above the King in four things, 1. In constitution, 2. Direction, 3. Limitation, 4. Coaction, p. 231.

- In what sense the King may do all things, p. 231, 232.

- The King under the moralitie of Laws. 2. Vnder Fundamentall Laws, not under punishment to be inflicted by himself, nor because of the eminency of his place, but for the physicall incongruity thereof, p. 232, 233.

- If, and how the King may punish himself? p. 233.

- That the King transgressing in a hainous manner, is under the Coaction of Law, proved by seven Arguments, p. 234, 235, seq.

- The Coronation of a King, who is supposed to be a just Prince, yet proveth after a Tyrant, is conditionall, and from ignorance, and so unvoluntary; and in so far, not obligatory in Law, p. 234, 235.

- Royalists confesse, a Tyrant in exercise may be dethroned, p. 235, 236.

- How the people is the seat of the power of Soveraigntie, p. 239, 240.

- The place, Psal. 51. Against thee onely have I sinned, &c. discussed, p. 241, 242.

- Israels not rising in arms against Pharaoh, examined, p. 245, 246, 247, 248, 249.

- And Judahs not working their own deliverance under Cyrus, p. 248, 249.

- A Covenant without the Kings concurrence lawfull, p. 249, 250, 251.

QUEST. XXVII. Whether or no, the King be the sole, supreme and finall Interpreter of the Law? Negatur, p. 252.

- He is not the supreme and peremptor Interpreter, p. 254.

- Nor is his will the sense of the Law, p. 252, 253.

- Nor is he the sole, and onely judiciall Interpreter of the Law, p. 253, 254, 255, seq.

- The state of the question. P. 257, 258,

- If Kings be absolute, a superiour Iudge may punish an inferiour Iudge, not as a Iudge, but an erring man. ibid.

- By Divine institution, all Covenants to restraine their power must be unlawfull. p. 258, 259.

- Resistance in some cases lawfull, p. 260, 261, 262.

- Six Arguments for the lawfulnesse of defensive Wars, in this Quest. 260. seq.

- Many others follow, Quest. 29. and 30. seq.

- The Kings Person in concreto, and his Office in abstracto, or which is all one, the King using his Power lawfully, to be distinguished, Rom. 13▪ p. 265.

- To command unjustly maketh not a higher power. p. 265.266.

- The person may be resisted, and yet the Office cannot be resisted, prooved by fourteene Arguments. p. 265, 266. seq.

- Contrary Objections of Royalists, and of the P. Prelate answered, p. 270, 271. seq.

- What we meane by the person and Office in abstracto in this dispute, we doe not exclude the person in concreto altogether, but only the person as abusing his power, we may kill a person as a man, and love him as a sonne, father, wife, according to Scripture, p. 272, 273, 274.

- We obey the King for the Law, and not the Law for the King, p. 275, 276.

- The loosing of habituall and actuall Royalty different, p. 276.

- Ioh. 19.10. Pilates power of crucifying Christ, no Law-power given to him of God, its proved against Royalists by six Arguments, p. 280.

- The place 1 Pet. 2.18. discussed, ibid.

- Patient bearing of injuries, and resistance of injuries compatible in one and the same subject, ibid.

- Christs non-resistance hath many things rare and extraordinary, and so is no leading rule to us, p. 315.

- Suffering is either commanded to us comparatively only, that we rather choose to suffer then deny the truth: or the manner only is commanded, that we suffer with patience, p. 317, 318. & sequent.

- The Physicall act of taking avvay the life, or of offending, vvhen commanded by the Lavv of self defence, is no murther, p. 321.

- We have a greater dominion over our goods and members, (except in case of mutilation, vvhich is a little death) then over our life, p. 321.

- To kill is not of the nature of self defence, but accidentall thereunto, ibid.

- Defensive vvar cannot be vvithout offending, p. 323.

- The nature of defensive and offensiue Warr••. p. 324, 325.

- Flying is resistance, p. 325, 326.

QUEST. XXXI. Whether selfe-defence by opposing violence to unjust violence be lawfull, by the Law of God, and Nature? Affirm. p. 326, 327.

- Self-defence in man naturall, but Modus, the way must be rationall and just. p. 327.

- The method of selfe-defence. ibid.

- Violent re-offending in selfe-defence the last remedy. p. 328.

- Its Physically unpossible for a Nation to fly in the case of persecution for Religion, and so they may resist in their owne self-defence. p. 328.

- Tutela vitae proxima, and remota. p. 329.

- In a remote posture of selfe-defence, we are not to take us to re-offending, as David was not to kill Saul when he was sleeping, or in the Cave, for the same cause, ibid.

- David would not kill Saul, because he was the Lords Anoynted, p. 330.

- The King not Lord of chastity, name, conscience, and so may be resisted, p. 331.

- By universall and particular nature, selfe-defence lawfull, proved by divers Arguments, p. 330.

- And made good by the testimony of Iurists, p. 331.

- The love of our selves the measure of the love of our neighbour, and inforceth selfe-defence, p. 332.

- Nature maketh a private man his owne Iudge and Magistrate when the Magistrate is absent, and violence is offered to his life, as the Law saith, p. 334, 335.

- Selfe-defence how lawfull it is, p. 333, 334, 335.

- What presumption is from the Kings carriage to the two Kingdomes, are in Law sufficient grounds of defensive warrs, p. 336, 337.

- Offensive and defensive warrs differ in the event and intentions of men, but not in nature and spece, nor Physically. p. 336, 337, 338.

- Davids case in not killing Saul, nor his men, no rule to us, not in our

- lawfull defence, to kill the Kings Emissaries, the cases farre different, p. 338, 339.

- David warrantably raised an Army of men to defend himselfe against the unjust violence of his Prince Saul, p. 340, 341, 342.

- Davids not invading Saul, and his men, who did not aime at Arbitrary Government, at subversion of Lawes, Religion, and extirpation of those that worshipped the God of Israel and opposed Idolatry, but only pursuing one single person, farre unlike to our case in Scotland and England now, p. 342.343.

- Davids example not extraordinary, p. 343, 344.

- Elisha's resistance proveth defensive warrs to be warrantable, p. 344, 345

- Resistance made to King Vzziah by eighty valiant Priests proveth the same, p. 346, 347, 348.

- The peoples rescuing Ionathan proveth the same, p. 348, 349.

- Libnah's revolt proveth this, p. 349.

- The City of Abel defended themselves against Ioab King Davids Generall, when he came to destroy a City for one wicked conspirator, Sheba his sake, p. 349, 350.

QUEST. XXXIII. Whether or no Rom. 13.1. make any thing against the lawfulnesse of defensive warrs? Neg. p. 350.

- The King not only understood, Rom. 13. p. 351.352.

- And the place Rom. 13. discussed. p. 352, 353, 354.

QUEST. XXXIV. Whether Royalists prove by cogent reasons, the unlawfulnesse of defensive warrs. p. 355.

- Objections of Royalists answered, p. 355, 356, 357. seq.

- The place Exod. 22.28. Thou shalt not revile the Gods, &c. answered, p. 357.

- And Eccles. 10.20. p. 358.

- The place Eccles. 8.3, 4. Where the word of a King is, &c. answered. p. 357, 358.

- The place Iob 34.18. answered, p. 359.

- And, Act. 23.3. God shall smite thee thou whited wall, &c. p. 359, 360, 361.

- The Emperours in Pauls time not absolute by their Law, p. 361.

- That objection that we have no practise for defensive resistance, and that the Prophets never complaine of the omission of the duty of resistance of Princes answered, p. 163, 164, 165.

- The Prophets cry against the sin of non-resistance, when they cry against the Iudges, because they execute not judgements for the oppressed. p. 365, 366. seq.

- Iudahs subjection to Nebuchadnezar a conquering Tyrant, no warrant for us to subject our selves to tyrannous acts. p. 363, 364, 365.

- Christs subjection to Caesar nothing against defensive warrs, p. 365, 366.

- Tertullian neither ours nor theirs in the question of defensive warrs, p. 370, 371, 372.

QUEST. XXXVI. Whether the King have the power of warre only? Negatur. p. 372, 373.

- Inferiour Iudges have the power of the sword no lesse then the King. p. 372, 373.

- The people tyed to acts of charity, and to defend themselves, the Church, and their posterity against a forraigne enemy, though the King forbid. p. 373, 374.

- Flying unlawfull to the States of Scotland and England now, Gods Law tying them to defend their Country. p. 374.

- Parliamentary Power a fountain-power above the King, p. 376, 377.

QUEST. XXXVII. Whether the Estates of Scotland are to help their Brethren the protestants in England against Cavaliers? Affirmatur, proved by 13. Arg. p. 378. seq.

- Helping of neighbour Nations lawfull, divers opinions concerning the point. p. 378, 379.

- The Law of Aegypt against those that helped not the oppressed, p. 380.

QUEST. XXXVIII. Whether Monarchy be the best of Governments. Affir. p. 384.

- Whether Monarchy be the best of Governments hath divers considerations, in which each one may be lesse or more convenient. p. 384, 385.

- Absolute Monarchy is the worst of Governments. p. 385.

- Better want power to doe ill as have it, ibid.

- A mixture sweetest of all Governments, p. 387.

- Neither King nor Parliament have a voyce against Law and reason, ibid.

QUEST. XXXIX. Whether or no, any Prerogative at all above the Law be due to the King? Or if jura majestatis be any such Prerogative? Negatur, p. 389.

- A threefold supreme power, ibid.

- What be jura regalia, p. 390, 391.

- Kings confer not honours from their plenitude of absolute power, but according to the strait line and rule of Law, justice, and good deserving, ibid.

- The Law of the King, 1 Sam. 8.9, 11. p. 392, 393.

- Difference of Kings and Judges, ibid.

- The Law of the King, 1 Sam. 8.9, 11. No permissive Law such as the Law of divorce, p. 394.

- What dominion the King hath over the goods of the subjects, p. 395, 396, 397.

QUEST. XL. Whether or no, the people have any power over the King, either by his Oath, Covenant, or any other way? Affirmed, p. 398, 399.

- The people have power over the King, by reason of his Covenant and Promise, ibid.

- Covenants and promises violated, infer Coaction, de jure, by Law, though not de facto, p. 399, 400.

- Mutuall punishments may be, where there is no relation of superioritie and inferioritie, p. 399, 400, 401.

- Three Covenants made by Arnisaeus, ibid.

- The King not King while he swear the oath, and be accepted as King by the people. ibid.

- The oath of the Kings of France, ibid.

- Hu. Grotius, setteth down seven cases, in which the people may accuse, punish, or dethrone the King, p. 403, 404.

- The Prince a noble Vassal of the Kingdom, upon four grounds, p. 405.

- The covenant had an oath annexed to it, ibid.

- The Prince is but as a private man in a contract. p. 406.

- How the Royall power is immediately from God, and yet conferred upon the King by the people, p. 407, 408, 409.

QUEST. XLI. Whether doth the P. P. with reason ascribe to us the doctrine of Jesuites, in the Question of lawfull defence? Negatur, p. 410, 411, 412.

- That Soveraignty is originally and radically in the people, as in the Fountain, was taught by Fathers, ancient Doctors, sound Divines, Lawyers, before there was a Jesuite, or a Prelate whelped, in rerum natura, p. 413.

- The P. P. holdeth the Pope to be the Vicar of Christ, p. 414, 415.

- Iesuites tenets concerning Kings, p. 415, 416, 417.

- The King not the peoples Deputie by our doctrine; it is onely the calumnie of the P. Prelate, p. 417, 418.

- The P. P. will have power to act the bloodiest tyrannies on earth, upon the Church of Christ, the essentiall power of a King, ibid.

QUEST. XLII. Whether all Christian Kings are dependent from Christ, and may be called his Vicegerents, Negatur, p. 422.

- Why God as God, hath a man a Vicegerent under him, but not as Mediator, p. 422, 423.

- The King not head of the Church, ibid.

- The King a sub-mediator, and an under redeemer, and a sub-priest to offer sacrifices to God for us, if he be a Vicegerent, p. 423.

- The King no mixt person, ibid.

- Prelates deny Kings to be subject to the Gospel, p. 426, 427.

- By no Prerogative Royall, may the King prescribe religious observances, and humane ceremonies in Gods worship, p. 424, 425.

- The P. P. giveth to the King a power Arbitrary, supreme and independent to govern the Church, p. 429, 430.

- Reciprocation of subjections of the King, to the Church, & of the Church to the King, in divers kindes, to wit of Ecclesiasticall and civill subjection, are no more absurd, then for Aarons Priest to teach, instruct and rebuke Moses, if he turne a tyrannous Achab, and Moses to punish Aaron, if he turn an obstinate Idolator, p. 430, 4••3

QUEST. XLIII. Whether the King of Scotland be an absolute Prince, having prerogatives above Laws and Parliaments? Negatur. p. 433, 434.

- The King of Scotland subject to Parliaments by the fundamentall Lawes, Acts, and constant practises of Parliaments, ancient and late in Scotland, p. 433, 434, 435, 436. seq.

- The King of Scotlands Oath at his Coronation, p. 434.

- A pretended absolute povver given to K. Iames 6. upon respect of personall indowments, no ground of absolutenesse to the King of Scotland, p. 435, 436.

- By Lawes and constant practises the Kings of Scotland subject to Lawes and Parliaments, proved by the fundamentall Law of elective Princes, and out of the most partiall Historicians, and our Acts of Parliament of Scotland, p. 439, 440.

- Coronation oath, ibid.

- And again at the Coronation of K. James the 6. that oath sworn; and again, 1 Par. K. Jam. 6. ibid. & seq. p. 452, 453.

- How the King is supreme Iudge in all causes, p. 437.

- The power of the Parliaments of Scotland, ibid.

- The confession of the faith of the Church of Scotland, authorized by divers Acts of Parliament, doth evidently hold forth to all the reformed Churches, the lawfulnesse of defensive Wars, when the supreme Magistrate is misled by wicked Counsell, p. 440, 441, 442.

- The same proved from the Confessions of Faith in other reformed Churches, ibid.

- The place, Rom. 13. exponed in our Confession of Faith, p. 441, 442, 443.

- The Confession not onely Saxonick, exhibited to the Councell of Trent, but also of Helvetia, France, England, Bohemia, prove the same, p. 444, 445.

- William Laud, and other Prelates, enemies to Parliaments, to States, and to the Fundamentall Laws of the three Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland, p. 446, 447, 448.

- The Parliament of Scotland doth regulate, limit, and set bounds to the Kings power, p. 448, 449,

- Fergus the first King, not a Conquerour, p. 449.

- The King of Scotland below Parliaments, considerable by them, hath no negative voice, p. 450, 451, seq.

QUEST. XLIV. Generall results of the former doctrine in some few Corrolaries, in 22 Questions. p. 454, 455.

- Concerning Monarchy, compared with other forms, p. 454.

- How Royaltie is an issue of nature, p. 454, 455.

- And how Magistrates as Magistrates be naturall, p. 455.

- How absolutenesse is not a Ray of Gods Majestie, ibid.

- And resistance not unlawfull, because Christ and his Apostles used it not in some cases, p. 456, 457.

- Coronation is no ceremony, p. 457.

- Men may limit the power that they gave not, p. 457, 458.

- The Common-wealth, not a pupill or minor properly, p. 459.

- Subjects not more obnoxious to a King, then Clients, Vassals, Children, to their Superiours, p. 459, 460.

- If subjection passive be naturall, p. 461.

- Whether King Uzziah was dethroned, p. 461, 462.

- Idiots and children not compleat Kings, children are Kings in destination onely, p. 462.

- Deniall of passive subjection in things unlawfull, not dishonourable to the King, more then deniall of active obedience in the same things, p. 463.

- The King may not make away, or sell any part of his Dominions, p. 463, 464.

- People may in some cases conveen without the King, p. 464.

- How, and in what meaning, subjects are to pay the Kings debts, p. 465.

- Subsidies the Kingdoms due, rather then the Kings, p. 465, 466.

- How the Seas, Ports, Forts, Castles, Militia, Magazeen, are the Kings, and how they are the Kingdoms, p. 466.

L. An. Senecæ Octavia. Nero, Seneca.

Sen. Nihil in propinquos temerè constitui decet.

Ner. lustum esse facile est, cui vacat pectus metu.

Sen. Magnum timoris remedium clementia est.

Ner. Extinguere hostem, maxima est virtus ducis.

Sen. Servare cives major est patriæ patri.

Ner. Præcipere mitem convenit pueris senem.

Sen. Regenda magis est servida adolescentia.

Ner. AEtate in hac satis esse consilii reor.

Sen. Vt facta superi comprobent semper tua.

Ner. Stultè verebor, esse cum faciam, Deos.

Sen. Hoc plus verere, quod licet tantum tibi.

Ner. Fortuna nostra cuncta permittit mihi.

Sen. Crede obsequenti parcius : levis est Dea .

Ner. Inertis est nescire quod liceat sibi.

Sen. Id facere laus est, quod decet, non quod licet.

Ner. Calcat jacentum vulgus.

Se. Invifum opprimit.

Ner. Ferrum tuetur principem.

Sen. Meliùs fides.

Ner. Decet timeri Caesarem.

Sen. At plus diligi.

Ner. Metuant necesse est.

Sen.Quicquid exprimitur grave est.

Ner. Iussisque nostris pareant.

Sen. Iusta impera.

Ner. Statuam ipse.

Sen. Que consensus efficiat rata.

Ner. Despectus ensis faciet.

Sen. Hoc absit nefas.

The PREFACE.↩

WHo doubteth (Christian Reader) but innocencie must be under the courtesie and mercy of malice, and that it is a reall martyrdome, to be brought under the lawlesse Inquisition of the bloody tongue? Christ, the Prophets and Apostles of our Lord, went to Heaven with the note of Traytors, Seditious men, and such as turned the world upside down: calumnies of treason to Caesar, were an ingredient in Christs cup, and therefore the author is the more willing to drink of that cup that touched his lip, who is our glorious forerunner: what if conscience toward God, and credit with men, cannot both go to heaven with the Saints, the author is satisfied with the former companion, and is willing to dismisse the other. Truth to Christ, cannot be treason to Caesar, and for his choise he judgeth truth to have a nearer relation to Christ Jesus, then the transcendent and boundlesse power of a mortall Prince.

He considered that Popery and defection had made a large step in Britain, and that Arbitrary Government had over-swelled all banks of Law, that it was now at the highest float, and that this sea approaching the farthest border of fancied absolutenes, was at the score of ebbing: and the naked truth is, Prelats, a wild and pushing cattle to the lambs and flock of Christ, had made a hideous noyse, the wheeles of their chariot did run an equall pace with the blood-thirsty mind of the Daughter of Babell. Prelacie, the daughter planted in her mothers blood, must verifie that word, As is the mother, so is the daughter: why, but [unnumbered] do not the Prelates now suffer? True, but their suffrings are not of blood, or kindred, to the calamities of these of whom Lactantius saith, l. 5. c. 19. O quam honesta volunt ate miseri erant. The causes of their suffring are, 1. Hope of gain and glory, stirring their Helme to a shoare they much affect; even to a Church of Gold, of Purple, yet really of clay and earth. 2. The lye is more active upon the spirits of men, not because of its own weaknesse, but because men are more passive in receiving the impressions of error, then truth; and opinions lying in the worlds fat wombe, are of a conquering nature, what ever notions side with the world, to Prelates and men of their make are very efficacious.

There is another cause of the sicknesse of our time; God plagued Heresie, to beget Atheisme and security, as Atheisme and security had begotten Heresie, even as clouds through reciprocation of causes engender rain, rain begate vapours, vapours clouds, and clouds rain, so do sins overspread our sad times in a circular generation.

And now judgement presseth the kingdoms, and of all the heaviest judgements the sword, and of swords the civill sword, threatneth vastation, yet not, I hope, like the Roman civill sword, of which it was said,

Bella geri placuit nullos habitura triumphos.

I hope this war shalbe Christs Triumph, Babylons ruine.

That which moved the author, was not as my excommunicate adversary, [1] like a Thraso, saith, the escapes of some pens, which necessitated him to write, for many before me hath learnedly trodden in this path; but that I might adde a new testimony to the times.

I have not time to examine the P. Prelates Preface, only, I give a tast of his gall in this preface, and of a virulent peece, of his (agnosco stylum et genium Thrasonis) In [unnumbered] which he laboureth to prove how inconsistent presbyteriall government is with Monarchy, or any other government.

1 He denyeth that the Crown and Scepter is under any coactive power of Pope, or Presbiterie, or censurable, or dethroneable: to which we say, Presbyteries professe that Kings are under the coactive power of Christs keyes of discipline, and that Prophets and Pastors, as Ambassadors of Christ, have the keyes of the kingdom of God, to open and let in beleeving Princes, and also to shut them out, if they rebel against Christ; the law of Christ excepteth none, Mat. 16.19. Mat. 18.15, 16. 2 Cor. 10.6. Jer. 1.9.18. if the Kings sins may be remitted in a ministeriall way, as Joh. 20.23, 24. as Prelates and their Priests absolve Kings; we think they may be bound by the hand that loosed, Presbyteries never dethroned Kings, never usurped that power; Your father P. Prelate, hath dethroned many Kings; I mean the Pope, whose power, [2] by your own confession cap. 5. pag. 58. differeth from yours by divine right, only in extent.

2 When sacred Hierarchy, the order instituted by Christ, is overthrown, what is the condition of Soveraignty? Ans. Surer then before, when Prelates deposed Kings. 2. I fear Christ shall never own this order.

3 The Mitre cannot suffer, and the Diadem be secured. Ans. Have Kings no pillars to their thrones, but Antichristian Prelates. Prelates have trampled Diadem and Scepter under their feet, as histories teach us.

4 Doe they not (Puritans) magisterially determine, that Kings are not of Gods creation by Authoritative Commission; but only by permission, extorted by importunity, and way given, that they may be a scourge to a sinfull people? Ans. Any unclean spirit from Hell, could not speak a blacker lye, we hold that the King, by office, is the Churches nurse father, [unnumbered] a sacred Ordinance, the deputed power of God; but by P. P. his way, all inferior Judges, and Gods Deputies on earth, who are also our fathers in the fifth Commandements stile, are to be obeyed by no Divine law; the King misled by P. Prelates, shall forbid to obey them, who is, in right-down truth, a mortall civill Pope, may loose and liberate subjects from the tye of a Divine law.

5 His inveying against ruling Elders, and the rooting out of Antichristian Prelacie, without any word of Scripture on the contrary, I passe as the extravagancy of a male-content, because he is deservedly excommunicated for Perjury, Popery, Socinianisme, Tyranny over mens conscience, and invading places of civill dignity, and deserting his calling, and the camp of Christ, &c.

6 None were of old anoynted, but Kings, Priests and Prophets, who then more obliged, to maintain the Lords Anoynted, then Priests and Prophets? The Church hath never more beauty and plenty under any government, then Monarchy, which is most countenanced by God, and magnified by Scripture. Ans. Pastors are to maintain the rights of people, and a true Church, no lesse then the right of Kings; but Prelates the Court Parasites, and creatures of the King, that are born for the Glory of their King, can do no lesse then professe this in words, yet it is true, that Tacitus writeth of such, Hist. l. 1. Libentius cum fortuna principis, quam cum principe loquuntur: and it is true, that the Church hath had plenty under Kings, not so much, because they were Kings, as because they were godly and zealous: except the P. P. say, That the oppressing Kings of Israell and Judah, and the bloody horns that made war with the Lamb, are not Kings. In the rest of the Epistle, he extols the Marques of Ormond with base flattery, from his Loyalty to the King, and his more then Admirable prudence in the Treaty of Cessation with the Rebells; a woe is due to this false prophet, [unnumbered] who calleth Darknesse Light, for the former was abominable, and perfidious Apostacy from the Lords cause, and people of God, whom he once defended, and the Cessation was a selling of the blood of many hundred thousand protestants, Men, Women, and sucking Children.

This cursed P. hath written of late a Treatise against the Presbyteriall government of Scotland, [3] in which there is a bundle of lyes, hellish calumnies, and grosse errors.

The first lye is, that we have Lay-Elders, whereas, they are such as rule, But labour not in the word and doctrine, 1 Tim. 5.7. pag. 3.

2. The second lye, that Deacons who only attend Tables, are joynt Rulers with Pastors, pag. 3.

3. That we never, or little use the lesser excommunication, that is, debarring from the Lords Supper. Pag. 4.

4. That any Church judicature in Scotland, [4] exacteth pecuniary mulcts, and threaten excommunication to the non-payers, and refuseth to accept the repentance of any who are not able to pay: the civill magistrate only fineth for Drunkennesse, and Adultery, Blaspheming of God, which are frequent sins in Prelates.

5 A calumnie it is to say, That ruling Elders are of equall authority to Preach the Word, as Pastors, Pag. 7.

6. That Lay-men are members of Presbyteries or generall Assemblies; Buchanan, and Mr. Melvin, [5] were Doctors of Divinity: and could have taught such an Asse as Jo. Maxwell. [6]

7. That exspectants are intruders upon the sacred function, because as sons of the Prophets, [7] they exercise their gifts for tryall in Preaching.

8. That the Presbytery of Edinbrough hath a superintending power, [8] because they communicate the affaires of [unnumbered] the Church, and writ to the Churches, what they hear Prelates and Hell devise against Christ and his Church.

9. That the King must submit his Scepter to the Presbytery; the Kings Scepter is his Royal office, which is not subject to any judicature, [9] no more then any lawfull ordinance of Christ; but if the King as a man, blaspheme God, murther the innocent, advance Belly-gods, (such as our Prelates for the most part were) above the Lords inheritance, the Ministers of Christ are to say, The King troubleth Jsraell, and they have the keyes to open and shut heaven to, and upon the King, if he can offend.

[10]10. That King James said, a Scottish Presbytery, and a Monarchy, agreeth as well as God and the Devill, is true, but King James meant of a wicked King; else he spake as a man.

[11]11. That the presbytery out of pride refused to answer King James his Honourable messengers, is a lye, they could not in businesse of high concernment, return a present answer to a Prince, seeking still to abolish Presbyteries.

12. Its a lye, that all sins, even all civil businesse, come under the cognizance of the Church, for only sins, as publikely scandalous, fall under their power, Mat. 18.15, 16, 17. &c. 2 Thess. 3.11. 1 Tim. 5.20. It is a calumnie that they search out secret crimes, or that ever they disgraced the innocent, or devided families, where there be flagrant scandals, and pregnant suspitions; of scandalous crimes, they search out these, as the incest of Spotswood, P. P. of Saint Andrewes, with his own daughter; the adulteries of Whiteford, P. P. of Brichen, whose Bastard came weeping to the Assembly of Glasgow in the armes of the whore: [12] these they searched out, but not with the damnable oath ex officio, that the High Commission put upon innocents, to cause them accuse themselves, against the Law of nature.

[unnumbered]

13. The Presbytery hinder not lawfull merchandize; [13] scandalous exhortation, unjust suits of Law, they may forbid: and so doth the Scripture, as scandalous to Christians, 2 Cor. 6.

14. They repeal no civill Lawes, [14] they Preach against unjust and grievous lawes, as, Esa. cap. 10.1. doth, and censure the violation of Gods Holyday, which Prelates prophaned.

15. We know no Parochiall Popes, we turn out no holy Ministers, but only dumbe dogs, non-residents, scandalous, wretched, and Apostate Prelates.

16. Our Moderator hath no dominion, [15] the P. P. absolveth him, while he saith, All is done in our Church by common consent, p. 7.

17. It is true, we have no Popish consecration, such as P. P. contendeth for in the Masse, [16] but we have such as Christ and his Apostles used, in Consecrating the Elements.

18. If any sell the Patrimony of the Church, the Presbytery censures him; if any take buds of Malt, Meale, [17] Beeffe, it is no law with us, no more then the Bishops five hundred markes, or a yeares stipend that the intrant gave to the Lord Bishop for a church. And who ever took buds in these dayes, (as King James by the Earl of Dumbar, did buy Episcopacie at a pretended Assembly, by foule budding) they were either men for the Episcopall way, or perfidiously against their oath became Bishops, all personall faults of this kind, imputed to Presbyters, agree to them, under the reduplication of Episcopall men.

19. The leading men, that covered the sins of the dying man and so losed his soul, were Episcopall men: and though some of them were presbyterians, the faults of men cannot prejudice the truth of God; [18] but the Prelates alwayes cry out against the rigor of Presbyteries, in censuring [unnumbered] scandals, because they themselves do ill, they hate the light; now here the Prelate condemneth them of remissenesse in Discipline.

[19]20. Satan, a lier from the beginning, saith, The Presbyterie was a seminary and nursery of fiends, and contentions, & bloods: because they excommunicated murtherers against King James his will: which is all one as to say, Prophecying is a nurse of bloods, because the Prophets cryed out against King Achab, and the murtherers of innocent Naboth: the men of God must be either on the one side, or the other, or then preach against reciprocation of injuries.

21. It is false, that Presbyteries usurp both swords: because they censure sins, which the civill Magistrate should censure and punish. Elias might be said then to mix himselfe with the civill businesse of the Kingdom, because he prophecied against Idolators killing of the Lords Prophets, which crime the civill Magistrate was to punish. But the truth is, the Assembly of Glasgow, 1637. condemned the Prelates, because they being Pastors, would be also Lords of Parliament, of Session, of Secret Counsell, of Exchequer, Judges, Barons, and in their lawlesse High Commission, would Fine, Imprison, and use the sword.

[20]22. It is his ignorance, that he saith, A provinciall synod is an associate body chosen out of all judiciall Presbyteries, for all Pastors, and Doctors, without delegation, by vertue of their place and office, repaire to the Provinciall Synods, and without any choice at all, consult and voice there.

[21]23. It is a lye, That some Leading men rule all here; indeed Episcopall men made factions to rent the Synods: and though men abuse their power to factions, this cannot prove that Presbyteries are inconsistent with Monarchie; for then the Prelate, the Monarch of his Diocesian [unnumbered] rout, should be Anti-Monarchiall in a higher manner, for he ruleth all at his will.

24. The prime men, as Mr. R. Bruce the faithfull servant of Christ, was honoured and attended by all, because of his Suffering, Zeal, Holinesse, his fruitfull Ministery in gaining many thousand souls to Christ: So, though King James cast him off, and did swear, By Gods name he intended to be King, (the Prelate maketh Blasphemy a vertue in the King) yet King James sware he could not find an honest Minister in Scotland to be a Bishop, and therefore he was necessitated to promote false knaves; but he said sometimes, and wrote it under his hand, that Mr. R. Bruce was worthy of the half of his kingdom: but will this prove Presbyteries inconsistent with Monarchies? I should rather think, that Knave Bishops, by King James his judgement, were inconsistent with Monarchies.

25. His lyes of Mr. R. Bruce, excerpted out of the lying Manuscript of Apostat Spotswood, in that he would not but preach against the Kings recalling from exile some Bloody Popish Lords, to undo all, are nothing comparable to the Incests, Adulteries, Blasphemies, Perjuries, Sabbath-breaches, Drunkennesse, [22] Prophanity, &c. committed by Prelates before the Sun.

26. Our Generall Assembly is no other then Christs Court, Act. 15. made up of Pastors, Doctors, and Brethren or Elders.

27. They ought to have no negative vote, to impede the conclusions of Christ in his servants.

28. It is a lye, that the King hath no power to appoint time an•• place for the Generall Assembly; but his power is not privative to destroy the free Courts of Christ, but accumulative to ayd and assist them.

29. It is a lye, That our generall Assembly may repeal

[unnumbered]

Laws, command and expect performance of the King, or then excommunicate, subject to them, force & compell King, Judges, and all, to submit to them. They may not force the conscience of the poorest begger, nor is any Assembly infallible, nor can it lay bounds upon souls of Iudges, which they are to obey with blind obedience, their power is ministeriall, subordinate to Christs Law; and what civill Laws Parliaments make against Gods word, they may Authoritatively declare them to be unlawfull; as though the Emperour, Act. 15. had commanded Fornication and eating of blood, might not the Assembly forbid these in the Synod? I conceive the Prelates, if they had power, would repeal the Act of Parliament made, An. 1641. in Scotland, by his Majestie personally present, and the three Estates concerning the anulling of these Acts of Parliament, and Laws, which established Bishops in Scotland. E••g. Bishops set themselves as independent Monarchs, above Kings and Laws: and what they damne in Presbyteries and Assemblies, that they practise themselves.

[23]30. Commissioners from Burroughs, and Two from Edinbrough, because of the largenesse of that Church, not for Cathedrall supereminence, sit in Assemblies, not as sent from Burroughs, but as sent and Authorized by the Church Session, of the Burrough, and so they sit there in a Church capacity.

[24]31. Doctors both in Accademies, and in Parishes, we desire, and our Book of Discipline holdeth forth such.

32. They hold (I beleeve with warrant of Gods word) if the King refuse to reform Religion, the inferior Iudges and Assembly of Godly Pastors, and other Church Officers may reform; if the King will not kisse the Sun, and do his duty in purging the House of the Lord, [25] may not Eliah and the people do their duty, and cast out Baals Priests? Reformation of Religion is a personall act that [unnumbered] belongeth to all, even to any one private person according to his place.

33. They may swear a Covenant without the King, if he refuse; and Build the Lords House, 2 Chron. 15.9. themselves: and relieve and defend one another, when they are oppressed. For my acts and duties of defending my self and the oppressed, do not tye my conscience conditionally, so the King consent, but absolutely, as all duties of the Law of nature doe, Jer. 22.3. Prov. 24.11. Esa. 58.6. Esa. 1.17.

34. The P. P. condemneth our Reformation, because it was done against the will of our Popish Queen. This sheweth what estimation he hath of Popery, and how he abhorreth Protestant Religion.

35. They deposed the Queen for Her Tyranny, but Crowned her Son; all this is vindicated in the following Treatise.

36. The killing of the monstrous and prodigious wicked Cardinall in the Castle of St. Andrews, and the violence done to the Prelates, who against all Law of God and man obtruded a Masse service upon their own private motion, in Edinbrough An. 1637. can conclude nothing against Presbyteriall Government, except our Doctrine commend these acts as lawfull.

37. What was preached by the servant of Christ, whom p. 46. he calleth the Scottish Pope, is Printed, and the P. P. durst not, could not, cite any thing thereof as Popish or unsound, he knoweth that the man whom he so slandereth, knocked down the Pope and the Prelates.

38. The making away the fat Abbacies and Bishopricks, is a bloody Heresie to the earthly minded Prelate: the Confession of Faith commended, by all the Protestant Churches, as a strong bar against Popery, and the book of Discipline, in which the servants of God laboured [unnumbered] twenty yeares, with fasting and praying, and frequent advice and counsell, from the whole Reformed Churches, are to the P. P. a negative faith, and devote imaginations; its a lye, that Episcopacie by both sides was ever agreed on by Law in Scotland.

39. And was it a heresie that M. Melvin taught, that Presbyter and Bishop are one function in Scripture? and that Abbots and Priors were not in Gods book? dic ubi legis: and is this a proof of inconsistency of Presbyteries with a Monarchie?

40 It is a heresie to the P. P. that the Church appoynt a Fast, when King James appoynted an unseasonable Feast, when Gods wrath was upon the Land, contrary to Gods word, Esa. 22.12, 13, 14. and what, will this prove Presbyteries to be inconsistent with Monarchies?

[26]41. This Assembly is to judge, what Doctrine is treasonable; what then? Surely the secret Counsell and King, in a constitute Church is not Synodically to determine what is true or false Doctrine, more then the Roman Emperor could make the Church Canon, Act. 15.

42. M. Gibson, M. Black, preached against King James his maintaining the Tyranny of Bishops, his sympathizing with Papists and other crying sins, and were absolved in a generall Assembly, shal this make Presbyteries inconsistent with Monarchie? Nay, but it proveth only, that they are inconsistent with the wickednesse of some Monarchies; and that Prelates have been like the four hundred false prophets that flattered King Achab; and these men that preached against the sins of the King, and Court, by Prelates in both Kingdomes, have been imprisoned, Banished, their Noses ript, their cheeks burnt, their eares cut.

43. The Godly men that kept the Assembly of Aberdeen, [unnumbered] An. 1603. did stand for Christs Prerogative when K. James took away all generall Assemblies, as the event proved; and the King may with as good warrant inhibit all Assemblies for Word and Sacraments, as for Church Discipline.

44. They excommunicate not for light faults and trifles as the Lyar saith: our Discipline saith the contrary.

45. This Assembly never took on them to chose the Kings Counsellours, but these who were in authority took K. James, when he was a child, out of the Company of a corrupt and seducing Papist, Esme Duke of Lennox, whom the P. P. nameth, Noble, Worthy, of eminent indowments.

46. It is true, Glasgow Assembly 1637. voted down the High Commission, because it was not consented unto by the Church, and yet was a Church Judicature which took upon them to judge of the Doctrine of Ministers, and deprive them, and did incroach upon the Liberties of the established lawfull Church judicatures.

47. This Assembly might well forbid M. John Graham Minister, to make use of an unjust decree, it being scandalous in a Minister to oppresse.

48. Though Nobles, Barons, and Burgesses, that professe the truth, be Elders, and so Members of the generall Assembly, this is not to make the Church the House, and the Common-wealth the Hangings; for the constistuent Members, we are content to be examined by the patern of Synods, Act. 15. v. 22, 23. Is this inconsistent with Monarchie?

49. The Commissioners of the generall Assembly, are 1. A meer occasionall judicature. 2. Appointed by, and subordinate to the Generall Assembly. 3. They have the same warrant of Gods Word, that Messengers of the Synod, Act. 15. v. 22.27. hath.

[unnumbered]

50. The historicall calumnie of the 17. day of December, is known to all; 1. That the Ministers had any purpose to dethrone King James, and that they wrote to John L. Marquesse of Hamilton to be King, because K. James had made defection from the true Religion: Satan devised, Spotswood and this P. P. vented this, I hope the true history of this is known to all. The holiest Pastors, and professors in the Kingdom, asserted this Government, suffered for it, contended with authority only for sin, never for the power and Office; These on the contrary side were men of another stamp, who minded earthly things, whose God was the world. 2. All the forged inconsistency betwixt Presbyteries and Monarchies, is an opposition with absolute Monarchie; and concludeth with alike strength, against Parliaments, and all Synods of either side, against the Law, and Gospell, preached, to which Kings and Kingdoms are subordinate. Lord establish Peace and Truth.

[1]

Lex, Rex.

QUEST. I. In what sense Government is from God?↩

I Reduce all that I am to speak of the power of Kings, to the Author or efficient. 2. The matter or subject. 3. The form or power. 4. The end and fruit of their Government; And 5. to some cases of resistance. Hence,

Quest. I. Whether Government be warranted by a divine Law?

The question is, either of Government in generall, or of the particular species of Government; such as are Government by one only, called Monarchy; the Government by some chief leading men, named Aristocracie; the Government by the people, going under the name of Democracie. 2. We cannot but put difference betwixt the institution of the Office, to wit, Government, and the designation of person, or persons to the Office. 3. What is warranted by the direction of natures light, is warranted by the Law of nature, and consequently by a divine Law; for who can deny the Law of nature to be a divine Law?

That power of Government in generall must be from God: [27] I make good, 1. Because, Rom. 13.—1. there is no power but of God; the powers that be, are ordained of God. 2. God commandeth obedience, and so subjection of conscience to powers, Rom. 13.5. Wherefore we must be subject not onely for wrath (or civill punishment) but for conscience sake, 1 Pet. 2.13. Submit your selves to every ordinance of man for the Lords sake▪ whether it be to the King as Supreme, &c. Now God onely by a divine Law can lay a band [2] of subjection on the conscience, tying men to guilt, and punishment, if they transgresse.

[28]2. Conclus. All civill power is immediately from God in its root. In that, 1. God hath made man a sociall creature, and one who inclineth to be governed by man; then certainly, he must have put this power in mans nature: so are we by good reason taught by [29] Aristotle.

2. God and nature intendeth the policie and peace of mankinde, then must God and nature have given to mankinde, a power to compasse this end; and this must be a power of Government. I see not then why John Prelate, Master Maxwel the excommunicate P. of Rosse, who speak••th in the name [30] of I. Armagh, had reason to say, That he feared that we fancied, that the Government of Superiours was onely for the more perfit▪ but have no Authoritie over or above the perfit, N••c Rex, nec Lex, justo posita. He might have imputed this to the Brasilians, who teach, That every single man hath the power of the sword to revenge his own injuries, as [31] Molina saith.

QUEST. II. Whether or not, Government be warranted by the Law of nature.↩

AS domestick societie is by natures instinct, so is civill societie naturall, in radice, in the root, and voluntary, in modo, in the manner of coalescing. Politick power of Government, agreeth not to man, singly, as one man, except in that root of reasonable nature; but supposing that men be combined in societies, or that one family cannot contain a societie, it is naturall, that they joyn in a civill societie, though the manner of Union in a politick body; as [32] Bodine saith, be voluntary, Gen. 10.10. Gen. 15.7. and [33] Suarez saith, That a power of making Laws, is given by God as a property flowing from nature, Qui dat formam, dat consequ••ntia ad formam, Not by any speciall action or grant, different from creation, nor will he have it to result from nature, while men be united into one politick body: which Union being made, that power followeth without any new action of the will,

[34]We are to distinguish betwixt a power of Government, and a power of Government by Magistracy. That we defend our selves from violence by violence, is a consequent of unbroken and sin-lesse nature; but that we defend our selves by devolving our power over in the hands of one, or more Rulers, seemeth rather positively morall, then naturall, except that it is naturall for the childe to expect [3] help against violence, from his father: For which cause I judge that learned Senator [35] Ferdinandus Vasquius said well, [36] That Princedom, Empire, Kingdom, or Iurisdiction hath its rise from a positive and secundary law of Nations, and not from the law of pure Nature. [37] The Law saith, there is no law of Nature agreeing to all living creatures for superiority; for by no reason in Nature, hath a Boar dominion over a Boar, a Lyon over a Lyon, a Dragon over a Dragon, a Bull over a Bull; And if all Men be born equally free (as I hope to prove) there is no reason in Nature, why one Man should be King and Lord over another; therefore while I be otherwise taught by the forecasten Prelate Maxwell, I conceive all jurisdiction of Man over Man, to be as it were Artificiall and Positive, and that it inferreth some servitude, whereof Nature from the womb hath freed us, if you except that subjection of children to parents, and the wife to the husband; and the [38] Law saith, De jure gentium secundarius est omnis principatus. 2. This also the Scripture proveth, while as the exalting of Saul or David above their Brethren to be Kings, and Captains of the Lords people, is ascribed, not to Nature, (for King and Beggar spring of one clay-mettall) but to an act of Divine bounty and grace, above Nature, so Psal. 78.70, 71. He took David from following the Ewes, and made him King and feeder of his people, 1 Sam. 13.13.

There is no cause why Royallists should deny Government to be naturall, but to be altogether from God, and that the Kingly power is immediatly and only from God; because it is not naturall to us to subject to Government, but against Nature, and against the hair for us to resign our liberty to a King, or any Ruler or Rulers; for this is much for us, and proveth not but Government is naturall; it concludeth that a power of Government tali modo, by Magistracy, is not naturall, but this is but a Sophisme; a 〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉, ad illud quod est dictum 〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉〈 in non-Latin alphabet 〉 this speciall of Government, by resignation of our liberty, is not naturall; Ergo, power of Government is not naturall; it followeth not, a negatione sp••ciei non sequitur negatio generis, non est homo, ergo non est animal. [39] And by the same reason I may by an antecedent will, agree to a Magistrate and a Law, that I may be ruled in a politick Society, and by a consequent will onely, yea and conditionally onely agree to the penalty and punishment of the Law; and it is most true, no man by the instinct of Nature giveth consent to Penall Laws as Penall, for Nature doth not teach a man, nor incline his spirit to yeeld that his life shall be taken away by the sword, and his [4] blood shed, except in this remote ground, a man hath a disposition, that a veine be cutt by the Physitian, or a Member of his body cut off, rather then the whole body and life perish by some contagious disease; but here reason in cold blood, not a naturall disposition is the neerest prevalent cause, and disposer of the businesse. When therefore a communitie by natures instinct and guidance, incline to Government, and to defend themselves from violence; they do not by that instinct formally agree to Government by Magistrates; and when a naturall conscience giveth a deliberate consent to good Laws, as to this, He that doth violence to the life of a man, by man shall his blood be shed, Gen. 9.6. He doth tacitely consent that his own blood shall be shed; but this he consenteth unto consequently, tacitely, and conditionally. If he shall do violence to the life of his brother: Yet so as this consent proceedeth not from a disposition every way purely naturall. I grant, reason may be necessitated to assent to the conclusion, being as it were forced by the prevalent power of the evidence of an insuperable and invincible light in the premises, yet from naturall affections there resulteth an act of self-love, for self-preservation. So David shall condemn another rich man who hath many Lambs, and robbeth his poor brother of his one Lamb, and yet not condemn himself, though he be most deep in that fault, [40] 1 Sam. 12.5, 6. yet all this doth not hinder, but Government even by Rulers hath its ground in a secondary Law of nature, which Lawyers call, secundariò jus naturale, or jus gentium secundarium; a secondary Law of nature, which is granted by Plato, and denied by none of sound judgement in a sound sense, and that is this, Licet vim virepellere, It is lawfull to repeal violence by violence, and this is a speciall act of the Magistrate.

2. But there is no reason, why we may not defend by good reasons, that politick Societies, Rulers, Cities, and Incorporations, have their rise and spring from the secundary Law of nature: 1. Because by Natures Law, Family-Government hath its warrant; and Adam though there had never been any positive Law, had a power of governing his own family, and punishing malefactors; but as [41] Tannerus saith well, and as I shall prove God willing, this was not properly a Royall or Monarchicall power; and I judge by the reasoning of [42] Sotus, [43] Molina, and [44] Victoria. By what reason a Family hath a power of Government, and of punishing Malefactors, [45] that same power must be in a societie of men, Suppose that societie were not made up of Families, but of single persons; [5] for the power of punishing ill-doers doth not reside in one single man of a familie, or in them all, as they are single private persons, but as they are in a familie. But this argument holdeth not but by proportion; for paternall government, or a fatherly power of parents over their families, and a politick power of a Magistrate over many families, are powers different in nature, the one being warranted by natures law even in its species, the other being in its spece and kind warranted by a positive law, and in the generall only warranted by a law of nature.

2. If we once lay the supposition, [46] that God hath immediately by the law of nature appointed there should be a Government; and mediately defined by the dictate of naturall light in a communitie, that there shall be one, or many Rulers to governe the Communitie; then the Scriptures arguments may well be drawn out of the school of nature: as, 1. The powers that are, be of God; [47] therefore natures light teacheth, that we should be subject to these powers. 2. It is against natures light to resist the ordinance of God. 3. Not to feare him to whom God hath committed the sword, for the terror of evill doers. 4. Not to honour the publike rewarder of well-doing. 5. Not to pay tribute to him for his worke. Therefore I see not but [48] Govarruvias, [49] Soto, [50] Suarez, have rightly said, that power of Government is immediately from God, and this or this definite power is mediately from God, proceeding from God by the mediation of the consent of a Communitie, which resigneth their power to one or moe Rulers: and to me [51] Barclaius saith the same: quamvis populus potentiae largitor videatur, &c.

QUEST. III. Whether Royall Power and definite forms of Government be from God?↩