JOHN PONET,

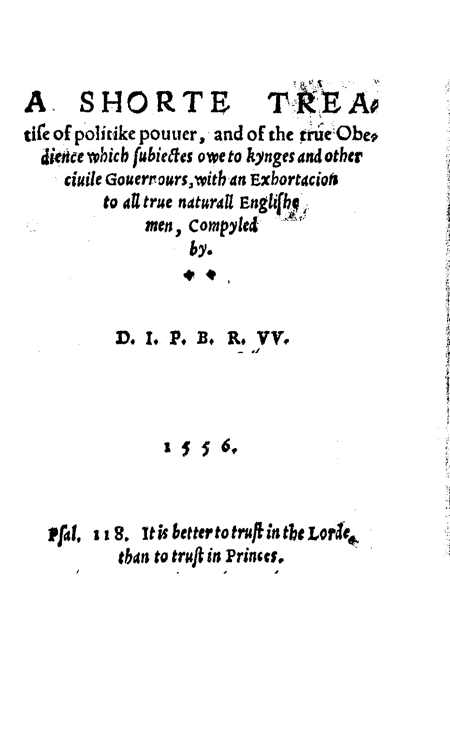

A Shorte Treatise of Politike Power and of the True Obedience which Subjectes owe to Kynges and other Civile Governours (1556)

[Created: 29 October, 2024]

[Updated: 29 October, 2024] |

|

This is an e-Book from |

Source

, A Shorte Treatise of politike pouuer, and of the true Obedience which subiectes owe to kynges and other ciuile Gouernours, with an Exhortacion to all true naturall Englishe men, Compyled by D. I. P. B. R. VV. (Strasbourg: Printed by the heirs of W. Köpfel, 1556).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Books/1556-Ponet_ShorteTreatise/Ponet_ShorteTreatise1556-ebook.html

John Ponet, A Shorte Treatise of politike pouuer, and of the true Obedience which subiectes owe to kynges and other ciuile Gouernours, with an Exhortacion to all true naturall Englishe men, Compyled by D. I. P. B. R. VV. (Strasbourg: Printed by the heirs of W. Köpfel, 1556).

Psal. 118. It is better to trust in the Lorde, than to trust in Princes.

Editor's Note: The original pamphlet was not paginated so I have added my own. Several abbreviations are used, such as ā ē ī ō ū which indicate that an "m" or an "n" has been omitted. When "the" preceeds a noun which starts with a vowell the words are run together, as in "the emperor" becomes "themperor", as with French.

I have found a modernised version of the pamphlet which is available online at this website.

Editor's Introduction

To make this edition useful to scholars and to make it more readable, I have done the following:

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs (which are used in the "citation tool" which is part of the "enhanced HTML" version of this text)

- retained the spaces which separate sections of the text

- created a "blocktext" for large quotations

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- reformatted margin notes to float within the paragraph

- inserted Greek and Hebrew words as images

Contents

- TO THE GENTIL READER, p. 4

- 1. WHEROF POLITIKE power groweth, werfore it was ordayned, and the right use and duetie of the same: &c, p. 5

- 2. WHETHER KINGES princes, and other governours have an obsolute power and authoritie over their subjectes, p. 23

- 3. WHETHER KINGES, princes, and other politike Governours be subjecte to Goddes lawes, and the positive lawes of theyr countreyes, p. 37

- 4. IN WHAT THINGES, AND how farre subjectes are bounden to obeie their princes and governours, p. 49

- 5. WHETHER ALL THE SVBJECTES goodes be the Kaysers and kinges owne, and that they maie laufully take them as their owne?, p. 81

- 6. WETHER IT BE laufull to depose an evil governour, and kill a tyranne, p. 100

- 7. WHAT CONFIDENCE is to be geven to princes and potentates, p. 129

- 8. AN EXHORTATION or rather a warnyng to the Lordes and Commones of Englande, p. 147

[4]

TO THE GENTIL READER.↩

COntent thy self to reade ouer this shorte treatise / wherin is neither heresie / felonye / nor treason / but all that is written here in fewe / is ment for thy pleyntifull benefite / necessary admonition / and faithfull instruction. And albeit the Printour is not sure / whether the autor be gone to God allready (as by the discourse of the mater he semeth to be) or yet still in this life / yet for as muche as the grauitie of the Worke / the sobrenesse of the stile / and the equitie of the cause ioyned with substauntial Profes / importe a mightye zeale / and aferuent care of the autor for his countrey / he is pleased to put furthe the Worke / to thintent the trauaile of the doer be not lost / neither true Englis he hartes frustrate of so worthie an instructiō / onles they wil willingly neglecte their owne saue garde / the state of their countrey / and the Preseruation of theyr posteritie. God geue thee (good reader) a will to forsee / an heart to per ceaue / and a iudgement to discerne thyne owne state in tyme / and in Christ hartily well to fare.

Amen.

[5]

VVHEROF POLITIKE povver grovveth, vverfore it vvas ordayned, and the right use and duetie of the same: &c.↩

AS OXEN, SHEPE, GOATES, ād suche other unreasonable creatures cānot for lacke of reason rule themselues, but must be ruled by amore excellent creature, that is mā: so mā, albeit he haue reason, yet bicause through the fall of the furst man, his reason is wonderfully corrupt, and sensualitie hathe goten the ouer hande, is not hable by himself to rule himself, but must haue a more excellent gouernour. The worldlinges thought, this gouernour was their owne reason. They thought, they might by their owne reason, doo what them lusted, nod onely in priuate thinges, but also in publike. Reason they thought to be the only cause, that men furst assembled together in companies, that common welthes were made, that policies were well gouerned and long continued: but mensee, that suche were utterly blynded and deceaued in their ymaginacions, their doinges and inuentiones (semed they neuer so wise) were so easili and so sone (contrary to their expectacion) ouerthrowen.

[6]

Wher is the Wisdome of the Grecianes? Wher is the fortitude of the Assirianes? wher is bothe the wis dome and force of the Romaynes become? All is uanished awaye, nothing almost lefte to testifie that they were, but that which well declareth, that their reason was not hable to gouerne them. Therfore were suche as were desirous to knowe the perfit and only gouernour of all, constrayned to seke further than them selues, and so at leynght to confesse, that it was one God that ruled all. By him we lyue, we haue our being, and be moued. He made us, and not we our selues. We be his people, and the shepe of his pasture. He made all thinges for man: and man he made for him self, to serue and glorifie him. He hathe taken upon him thordre and gouernement of man his chief creature, and prescribed him a rule, how he should behaue him self, what he should doo, and what he maye not doo.

This rule is the lawe of nature, furst planted and graffed only in the mynde of mā, thā after for that his mynde was through synne defiled, filled with darknes se, ād encōbred with many doubtes) set furthe in writing in the decaloge or ten cōmaundemētes: and after reduced by Christ our saueour ì to these two wordes: Thou shalt loue thy lorde God aboue all thinges, ād thy neighbour as thy self. The later part vvherof he also thus expoundeth: vvhat so euer ye vvill that men doo vnto you, doo ye euen so to them.

[7]

In this lawe is comprehended all iustice, the perfite waye to serue and glorifie God, and the right meane to rule euery man particularly, and all men generally: and the only staye to mayntayne euery cō mō wealthe. This is the touchestone to trye euery mā nes doinges (be he king or begger) whether they be good or euil. Bi this all mānes lawes be discerned, whe ther they be iuste or uniuste, godly or wicked. As for an example. Those that haue autoritie to make lawes in a common wealthe, make this lawe, that no pynnes shalbe made, but in their owne coūtrey. It semeth but a trifle. Yet if by this meanes the people maye be kept from idlenesse, it is a good and iuste lawe and pleaseth God. For idlenesse is a uice wherwith God is offēded: and the waye to offende him in breache of these commaundemētes: Thou shalt not steale, thou shalt not kill, thou shalt not be a horemonger, &c. For all these euilles come of idlenesse. On the other syde, if the people be well occupied in other things, and the people of an other countrey lyue by pynne making, and uttring them : thā if ther should be a lawe made, that they might not sell them to their neighbours of the other countrey, otherwise well occupied, it were a wicked and an uniuste lawe. For taking awaye the meane, wherby they lyue, a meane is deuised to kill them with famyne, and so is not onely this commaundement broken: Thou shalt not kill, but also the general lawe, that sayeth: Thou shalt [8] loue thy neighbour as thy self. And, vuhat so euer ye vuill that men do vnto you, euen so do you vnto thē. For you your selues vuold not be killed vuith hungre.

Likewise if ther be a lawe made, vtterly prohibiting any mā that can not lyue chaste, to marie: this is an vniuste, an vngodly and a wicked lawe. For it is an occasion, that wher with marieng, he might auoide synne: he not marieng dothe committe horedome in acte or thought contrary to Goddes will and commaundemēt: Thou shalt not cōmitte horedome

Agayn, a prince forceth his subiectes (vnder the name of request) to lēde him that they haue, which they doo vnwillingly: and yet for feare of a worse tourne, they must seme to be content therwith. Afterwarde he causeth to be assembled in a Parliamēt such as per chance lent nothing, or elles such as dare not displease him. They to please him, remit this general debte. This is a wicked, vngodly, and vniust lawe. For they doo not, as they wolde be done vnto, but be an occasion, that a great nombre be vndone, their children for lacke of sustenaunce perishe through famyne, and their seruavntes forced to steale, and perchaunce to cōmyt murther. So that if men will weigh well this order and lawe that God hathe prescribed to man, Thou shalt loue thy lord God aboue all thinges, and thy neighbour as thy self. And, what so euer ye will that men do vnto you, do ye euen the same vnto them: [9] they maye sone learne to trye good from euil, godlynesse from vngodlynesse, right from wrong.

And it is so playne and easie to be vnderstanden, that no ignoraunce cā or will excuse him that therin offendeth.

Against thoffendours of this lawe, ther was no corporal punishement ordayned in this worlde, til after the destruction of the worlde with the great floud. For albeit Cayn and lamech had committed horrible murthers, yet were they not corporally punished, but had a protection of God, that none should laufully hurte them. But after the flood, whan God sawe his gentilnesse and pacience could not worke his creatures to doo their dueties vnforced, but iniquitie preuailed and mischief daily encreaced, and one murthered, and destroyed an other: than was he constrayned to chaunge his lenitie into seueritie, and to adde corporal paynes to those that wold not folowe, but transgresse his ordinaunces. And so he made this lawe, which he declared to Noha: He that Sheadeth the bloud of man, his bloud Shal be Shead by man. For man is made after the ymage of God.

By this ordināce and lawe he instituteth politike power and geueth authoritie to mē to make more lawes. [10] For he that geueth man autoritie ouer the body and life of man, bicause he wolde haue man to lyue quietly with mā, that all might serue him quietly in holynes and righteousnes, all the dayes of their life, it can not be denyed, but he gaue him autoritie ouer goodes, landes, possessiones and all suche thinges as might bried controuersies and discordes, and so hyndre and let, that he might not be serued and glorified, as he requireth. This ordinaunce also teacheth makers of lawes, how they should behaue thē selues in making lawes: that is, to set aparte all affectiones, and to obserue an equalitie in paynes, that they be not greater or lesse, than the fault deserueth, and that they punishe not thinnocent or smal offendour for malice, and let the mightie and great thefe escape for affection. And out of this ordinaunce groweth and is grounded thautoritie for Magistrates to execute lawes: for lawes without execucion, be no more profitable, than belles without clappers. But whether this authoritie to make lawes, or the power to execute the same, shal be and remayne in one person alone, or in manie, it is not expressed, but lefte to the discreciō of the people to make so many and so fewe, as they thinke necessarie for the mayntenaunce of the state. wherupon in som places, they haue ben content to obey suche lawes, as were made by one, as the Israelites were with those that Moyses ordayned: the Lacedemones with those that Licurgus made, the Athenes [11] with those that Solon gaue them. And in some places with suche as were made by certayn outchosen men, as in Rome by the ten men. And in some they receaued none, but suche as all the multitude agreed Vnto. Likewise in some countreyes they were cōtent to be gouerned, and the lawes executed by one king or Iudge, in some places by many of the best sorte, in some places by the people of the lowest sorte, and in some places also by the king, nobilitie, and the people all together.

And these diuerse kyndes of states or policies hade their distincte names, as wher one ruled, a Monarchie: wher many of the best, Aristocratie: wher the multitude, Democratie: and wher all together, that is, a king, the nobilitie, and cōmones, a mixte sta te: which men by long continuance haue iudged to be the best sort of all. For wher that mixte state was exerciced, ther did the cōmon wealthe longest continue. But yet euery kynde of these states tended to one ende, that is, to the mayntenaunce of iustice, to the wealthe and benefite of the hole multitude, and not of the superiour and gouernours alone. And whan they sawe, that the gouernours abused their autoritie, they altred the state. As among the Israelites, for the iniquitie of the children of Samuel their iudge, from Iudges to kinges: among the Romaynes, for the tyrannye and oppression that [12] Tarquinius vsed ouer the people (as the chief occasion) and afterwarde for his sonnes lewdenesse (as the outwarde occasion) from kinges to Consules, and so from Consules (for their euil demeanour) to Decem viri and Triumviri, that is, to ten rulers and three rulers: and so from chaunge to chaunge, tyll it came to the state Imperial: yet alwayes preseruing and mayntening thautoritie, albeit they altred and chaunged the kinde of gouernement. For the Ethnikes themselues being ledde only by the lawe of nature and their owne reason, sawe that without politike power and autoritie, mankynde could not be preserued, nor the worlde continued. The riche wold oppresse the poore, and the poore seke the destruction of the riche, to haue that he hade: the mightie wold destroye the weake, and as Theodoretus sayeth, the great fishe eate vp the small, and the weake seke reuenge on the migh tie: and so one seking the others destruction, all at leynght shoulde be vndone and come to destruction. And bicause this authoritie and power, bothe to make lawes, and execute lawes, proceded from God, the holy goost in scripture calleth them Goddes: not for that they be naturally Godds, or that they be transubstantiated in to Goddes (for he sayeth, they shall dye like men, and in dede their workes declare them to be non other than men) but for thautoritie and power which they receaue of God, [13] to be his ministers here in earthe, in ruling and gouerning his people, and that the people should the rather obeye them, and haue them in honour and reuerence, according to his ordinaunce.

And the wonderfull prouidence of God is herein to be wel noted and considered, of all suche as loue and feare God, that in all places and countreyes wher Goddes worde hathe ben receaued and embraced, ther for the tyme the people folowed God, no tirannye could entre, but all the membres of the body sought the prosperitie and wealthe one of an other, for Goddes worde taught them so to doo. Thou shalt loue the lorde thy God (sayeth it) aboue all thinges, and thy neighbour as thy selfe. And, what ye will that men doo vnto you, doo you euen so vnto them. The frutes of his worde is loue one of an other, of what state or degree in this worlde so euer they be. And the state of the policies and common wealthes haue ben disposed and ordained bi God, that the headdes could not (if they wolde) oppresse the other membres. For as among the Lacedemonians certain men called Ephori were ordayned so see that the kinges should not oppresse the people, and among the [14] Romaynes, the Tribunes were ordayned to defende and mayntene the libertie of the people from the pride and iniurie of the nobles: so in all Christian realmes and dominiones God ordayned meanes, that the heads the prīces ād gouernours should not oppresse the poore people after their lustes, ād make their wil les their lawes. As in Germanye betwene thēperour ād the people, a Counsail or diet: in Fraūce and Englande, parliamentes, wherin ther mette and assembled of all sortes of people, and nothing could be done without the knowlage and consent of all. But wher the people haue forsaken God, and contēned utterly his worde, ther hathe the deuil by his ministers, occupied the hole countrey, and subuerted the good ordres, iustice and equalitie, that was in the common wealthe, and planted his unreasonable lustes for good lawes, as euery man maye see by the Realme of Vngarie which the Turke in our tyme hathe occupied. And wher the people haue not utterly forsaken God and his worde, but haue begonne to be weary of it: ther hathe not God suffred Tyrannes by and by to rush in, and to occupie the hole, and to suppresse the good ordres of the common wealthe, but by litel and litel hathe suffred them to crepe in, first with the head, than with an arme, and so after with a legge, and at leynght (were not the people penitent, and in tyme conuerted to God) to bring in the hole body, and to worke the feates of Tirannes, [15] as hereafter it shalbe declared.

This is so manifest in most places, that it shall not nede any particular example. Wherfore it shalbe the parte of all Christen men to take hede, that in forsaking God, they bring not iustly the deuil and tyrannes to reigne ouer them. And those that be called to councelles and parliamentes (and so to be makers of lawes, wherby the people should be bounden) not to neglecte their duetie, or to deceaue the people of the trust and confidence, that was put in them. For it is no litle daunger that maye therby folowe unto them, bothe in this worlde, and in the worlde to come. For that man that toke upon him to doo any thing for an other (being the thing neuer so litle of ualue) and therin did use him self either craftily, seking his owne gayne and profit, or shewe him self not diligent, or not passing what became of the matter committed to his trust, our elders being men of honestie, iudged and condemned for a most uile uarlet and unhonest persone: and being men of wisedome, made a lawe (which continueth til this daye) not only that he should make recompence for the hurt he did, but also that he should not be allowed afterwarde in the company or nombre of honest men, no more than an open these. And this they did not by will, but by reason, not rashly, but aduisedly, not by the moo voices, but by the more discrete headdes, bicause they sawe, that men could [16] not be alwayes present to doo their owne thinges, but of necessitie must use the helpe and trust of others. And again, nature hathe not made euery man apte for all thinges, but hathe made one man more mete for one purpose than an other: so that one hauing nede of an other, euery one should be glad to doo for an other, and all be tyed together in an undissoluble strong bande of frendship. And therfore was suche false and unfrendly dealing taken to be most uile, bicause it did uiolate two the chiefest uertues and most necessary thinges, without which mankynde coulde not contynue: faithe, and frēdship. For noman requireth an other, to doo any thing for him, whom he taketh not to be his frende, nor trusteth him, whom he thinketh not faithfull. And therfore they thought him to be a uery wicked and vile persone, and not worthy the name of a man, that at one tyme and in one thing should thus undoo the knot of frendship, and deceaue him, whom he coulde not haue hurted, onles he hade trusted him. Now if nature, reason, honestie and lawe dothe so greuously punishe him, and cast him out of all honest mennes companies, that is necligent in a trifle, how muche more ought he to be punished and cast out of all mennes sight, that is necligent in the greatest matiers? If he ought so sharpely to be vsed, that deceaueth one poore man: how muche more sharpely ought he to be punished, and [17] of all men to be abhorred (yea cast to the dogges) that deceaueth a hole Realme of ten or twentie hundred thousaunt persones? If he be thus to be abhorred and punished, that is required to doo an other mannes busynesse, and deceaueth him: how muche more ought they to be abhorred and hated, that take vpon them to doo for others, not desired but suyng for it: not called therto, but thrusting in them self: not prayed, but payeng, geuing many lyuereyes, procuring and making frendes to geue them their uoices, obteynyng of great mennes lettres, and ladies tokens, feasting freholders, and making great banketting cheare: not by the consent of the parte, but by force and streinght, with tropes of horsemen, billes, bowes, pykes, gonnes, and suche like kynde of qualityes.

If this opinion be had, and iudgement be geuen against a man that seketh his owne gayne with the losse of his frendes in small thinges: What opinion maye men haue, what iudgemēt shalbe geuen of those, that (to make them selues noble and riche) cutte the throtes of those that committed themselues, their wyues, their children, their goodes, yea and lyues vpon trust in to their handes?

If this iudgemēt be geuen for worldly thinges, what iudgemēt shalbe geuē of those that wilfully goo about to destroye mēnes soules, and to make thē a present to the deuil, so that they for a tyme maye be his deputies [18] here in earthe? If men doo thus abhorre and punishe suche unfaithfull and unhonest persones: how muche more will thalmightie God abhorre, condemne, and exercice his seuere iudgement on them, that thus abuse the autoritie geuen unto them by him, and deceaue and undoo those poore shepe of his, in whom (as his ministers) they put their trust?

Hearke, hearke (while tyme of repentaunce is) to the sentence of God, pronounced by the mouthe of his seruaunt and Prophet Esaias. VVo be vnto you (sayeth he) that make vnrighteous lauues, and deuise thinges vuhich be to harde to be kept, vuherby the poore are oppressed on euery syde, and thinnocentes of my people are theruuith robbed of iudgement, that vuydouues maye be your praye, and that ye maye robbe the fatherles. VVhat vuill ye doo in tyme of the visitacion and destruction that shall come from farre? To vuhom vuill ye runne for helpe? Or to vuhom vuill ye geue your honour, that he maye kepe it? that ye come not among the prisoners, or lye among the dead?

This terrible wo of euerlasting damnacion was spoken not only to Ierusalem, but to Germanie, Italie, Fraunce, Spayne, Englande, Scotlande, and all other countreyes and naciones, wher the like [19] vices shalbe committed. For God is iuste, and so hateth sinne, that he neuer leaueth it in any place vnpunished: but the more common it is, the greater plages and force dothe he vse to represse it: as we maye learne by thexamples of the cities Sodome and Gomor, and Ierusalem his owne citie. And besides the general plage, he whippeth the autors of it with som special scourge, that they maye be a spectacle, not only to those that are present, but also a remembraunce to all that be to come.

But perchaunce som (that be put in trust and autoritie to make statutes and lawes) will saye: Wee doo not willingli any thing against Goddes honour, or the wealthe of our countrey, or deceaue any that put their trust in vs.

If any suche thing folowe, it is by reason that we were ignoraunt.

Tell me, If beseche thee, if thou hadest hyred one to be thy shepehearde, and thy shepe should vnder his hande by his ignoraunce myscarie: or if thy horsekeper taking wages, should (through his necligence) suffre thy horse to perishe: woldest thou not compte him faulty and loke for amendes at his handes? Should ignoraunce excuse him? No, thou woldest saye, I hyred thee, and thou tokest it vpon thee. And so thou woldest not onely force hym to make satisfaction, but also woldest thinke it iuste to haue him punished besydes to make himself no more cōnyng [20] than the was, not to deceaue any that put their trust in him. Than thei are muche to blame, that being put in trust in Courtes and parliamentes to make lawes and statutes to the aduauncement of Goddes glorie, and conseruation of the liberties and common wealthe of their countrey, neglecte their office and charge, being appointed to be not only kepers of Goddes people, not of hogges, neither of horses and mules which haue no vnderstāding, but of that deare stocke which Christ purchaced with the price of his hart blood: but also as phisicianes and Surgeons, to redresse, reforme and heale, if any thing be amysse. And if a phisitian for lucre or other mennes pleasure, wold take vpon him the healing of a sore diseased per sone, and for lacke of knowlage or vpō other euil pur pose wold ministre thinges to hurt or kill the persone, were he not worthy to be taken and punished as a bocher and a man murtherer?

But ye will saye: we gaue credit to others, and they deceaued vs. Thinke ye, that this balde excuse will serue? Is it not written, that if the blynde leade the blynde, bothe shall fall in to the pitte? Did the plea that Eua made for offending in eating the forbidden apple (whan she sayed, the serpent had deceaued her) excuse her? Nothing lesse. She was not only her self therfore punished with suche paynes (as greater than deathe none could be deuised) hut also all her posteritie.

[21]

Other perhappes of you will saie: ye dare doo non otherwise. If ye did, ye should be taken for enemies of the gouernour, runne in to indignation, and so lose your bodies and goodes, and vndoo your children. O faynt heartes, Thinke ye, that your parentes had lefte you as ye be, if they had ben so faynt harted? Or thinke ye that this will serue your turne? Was it ynough for Adam our first father, whan he fell with bearing his wife companye in eating the forbidden apple, to saye, I durst not displease my wife: or to saye, as he sayed, The woman whome thou gauest me, gaue it me? No, it auailed not, but he and all his posteritie were plagued for his disobedience, as we and all that shall folowe vs, doo well fele, if we haue any feare of God before our eies.

Whan the brutishe commones of Israel were so importune vpon Aaron, that he for feare was fayne to make them the golden calfe: wherwith whan Moses sharpely charged him he excused him self, sayeng: alas Sir, this sedicious and rageing brutishe people wold nedes haue me perforce to doo it. God knoweth, it was sore against my will: did this excuse acquite him, trowe you? No surely. If he had not repented, he had ben as sure of hell fyre for his labour, as they be, which haue set vp or sayed the beastly popyshe masse, at [22] the furious enforcement of the brutishe commones or in pretense of obedience to the Quenes procedinges in Englande: onles they spedily repent, and renounce their wicked doing, as Aaron did his.

Thus ye haue hearde not only wherof politike power groweth, and of the true vse and duetie therof, but also what wilbe layed to their charge, that doo not their duetie in making of lawes. Now see, what is sayed by God to thexecutours of lawes: See what ye doo (Sayeth God) for ye execute not the iudgement of man, but of God. and what so euer ye iudge, it shall redounde to your selues. Let the feare of God therfore be before your eies, and doo all thinges with diligence. For with the lorde our God ther is non iniquitie, neither difference of persones, nor yet hathe he pleasure in rewardes or bribes.

But of the ministers of lawes and gouernours of realmes and contreyes, more shalbe sayed hereafter.

[23]

VVHETHER KINGES princes, and other gouernours haue an obsolute power and authoritie ouer their subiectes.↩

Forasmuche as those that be the Rulers in the worlde, and wolde be takē for Goddes (that is, the ministers and images of God here in earthe, thexāples and myrrours of all godlynesse, iustice, equitie, and other vertues) clayme and exercice an absolute power, which also they call a fulnesse of power, or prerogatiue to doo what they lust, and none maye gaynesaye them: to dispense with the lawes as pleaseth them, and frely and without correction or offence doo contrary to the lawe of nature, and other Goddes lawes, and the positiue lawes and customes of their countreyes, or breake them: and vse their subiectes as men doo their beastes, and as lordes doo their villanes and bondemen, getting their goodes from them by hoke and by crooke, with Sic volo, Sic iubeo, and spending it to the destruction of their subiectes: the miserie of this tyme requireth to examyne, whether they doo it rightfully or wrōgfully, that if it be right full, the people maie the more willingly obeie and re ceaue the same: if it be wrongful, that than those that vse it, maye the rather for the feare of God leaue it. For (no douht) God will come, and iudge the worlde with equitie, and reuēge the cause of the oppressed. Of the popes power (who compteth himself one, yea the [24] chief of these kinde of Goddes, yea aboue them all, and felowe to the God of Goddes) we minde not now to treate: nother is it requisite. For all men, yea half wise women and babes can well iudge, that his power is worthy to be laught at: and were it not bolstred and propped vp with sweorde ād fagot, it wolde (as it will notwithstanding) shortly ly in the myre, for it is not buylt on the rocke, but on the sande, not planted by the father of heauen, but by the deuil of hell, as the frutes doo manyfestly declare. But we will speake of the power of kynges and princes, and suche like potentates, rulers, and gouernours of common wealthes.

Before ye haue hearde, how for a great long tyme, that is vntil after the general flood, ther was no ciuile or politike power, and how it was thā furst ordayned by God him self, and for what purpose he ordayned it: that is (to comprehende all briefly) to mayntene iustice: for euery one doing his deutie to God, and one to an other, is but iustice. Ye haue hearde also, howe states, bodies politike, and common wealthes ha ue autoritie to make lawes for the mayntenaunce of the policie, so that they be not contrary to Goddes lawe and the lawes of nature: which, if ye note well the question before propouned whether kinges and princes haue an absolute power, shall appeare not doubtfull, or if any wolde affirme it, that he shall not be hable to maintene it. For first touching Goddes lawes [25] (by which name also the lawes of nature be comprehended) kinges and princes are not ioyned makers herof with God, so that therby of thē selues they might clayme any interest or autoritie to dissolue them or dispense with them, by this Maxime or principal, that he that maye knyt together, maye lose asondre: and he that maye make, maye marre: for before Magistrates were, Goddes lawes were. Neither can it be proued, that by Goddes worde they haue any autoritie to dispense or breake them: but that they be still commanded to doo right, to ministre iustice, and not to swarue, neither on the right hande or on the lefte. Than must it nedes folowe, that this absolute autoritie which they vse, must be mayntened by mannes reason, or it must nedes be an vsurpaciō: But what can reason saye? If it be not laufull, by no lawes (no neither by honestie) for any mannes seruaunt to altre his maisters (a mortal mannes) commaundement: can reason saye, it is laufull for any persone to altre Goddes cōmaundement, or breake it? That a mannes seruaunt maye be wiser than his maister, that he maye be iuster than his maister, that he maye see what is more profitable and necessarie to be done thā his maister, cōmonly it happeneth: and therfore he maye haue som apparēt cause, to altre or breake his maisters cōmaun dement. But to saye, that any creature is, or that any creature wolde seme in worde or dede, to be more wise than God, more iuste than God, more prudent [26] and circumspecte than God, or knoweth what is better for the creature than the creatour him self (as it must nedes be saied, that he dothe, that taketh vpon him to breake or dispence with Goddes will and commaundementes) what an horrible blasphemie is it? What luciferous presumpcion is it?

If we will not submit our selues to Goddes iudgement herein expressed by his worde, as Christianes should, let vs yet marke the sequele: and therby gather Goddes iudgement, as Ethnikes doo. For whan we haue wrought our wittes out, and deuised and done what we can, we can not so exclude God, but he will haue a saieng with vs.

Goddes worde, will and commaundement is, that he that wilfully killeth a man, shall also be killed by man: that is, the Magistrate. But this lawe hathe not ben obserued and all wayes executed, but kinges and princes vpon affection haue dispensed and broken it, graunting life and libertie to traitours, robbers, murtherours, &c.

But what hathe folowed of it? Haue they (whose offences haue ben so pardoned) after ward shewed them selues penitent to God, and thankfully profitable to the common wealthe? No, God and the commonwealthe haue hade no greater enemies. They haue added murther to murther, mischief to mischief, and of priuate malefactours, haue become publike, and of men killers, they haue at leinght growen [27] to be destroiers of their countrey, yea and many tymes of them that saued them from hanging and other iust paines of the lawe. And no maruail: for God dothe not oneli punishe the principalles and autors of suche mischief, but also those that be accessaries and mayntenours of it, and plageth iniquitie with iniquitie. Ye maie likewise see, what frutes haue folowed, wher popes, haue dispensed, that mariages might be made contrarie to Goddes lawes. We shall not nede to rehearse any? thende will declare all. But let vs leaue to reason that, wherein nothing can be saied for it. And let vs come to that, wherein somewhat maye be saied: that is, whether kinges and princes maye doo thinges contrary to the positiue lawes of their countrey. As for example.

It is a lawe positiue, that a meane kinde of apparail, or a meane kynde of diet should be vsed in a common wealthe, to thintent that men leauing thexcesse thereof, wherof many occasiones bothe to destroie nature and to offende God folowe, they might conuerte that they before euil spent, to the relief of the pouertie, or defense of their countrey.

For answer to this question, this diuision ought to be made, that ther be two kyndes of kinges, princes, and gouernours.

The one, who alone maye make positiue lawes, bicause the hole state and body of their countrey haue geuē, and resigned to them their authoritie so to doo: [28] which neuertheles is rather to be compted a tiranne than a king, as Dionisius, Philippus and Alexander were, who saued whom they wold ād spilt whom they lusted. And thother be suche, vnto whom the people haue not geuen suche autoritie, but kepe it them selues: as we haue before sayed cōcerning the mixte state.

True it is, that in maters indifferent, that is, that of them selues be neither good nor euil, hurtfull or profitable, but for a decent ordre: Kinges and Princes (to whom the people haue geuen their autoritie) maie make suche lawes, and dispense with them. But in maters not indifferent, but godly and profitably ordayned for the common wealthe, ther can they not (for all their autoritie) breake thē or dispense with them. For Princes are ordained to doo good, not to doo euil: to take awaie euil, not to increace it: to geue example of well doing, not to be procurers of euil: to procure the wealthe and benefite of their subiectes, and not to worke their hurt or vndoing. And in thempire wher (by the ciuile lawes) themperours claime, that the people gaue them their autoritie to make lawes, albeit they haue ben willing, and ofte attēpted to execute their autoritie, which som Pikethākes (to please them) saie they haue by the lawes, yet haue they ben forced of them selues to leaue of their enterprise. But such as be indifferent expounders of the lawes, be of that minde that we before haue declared: and therfore [29] make this a general conclusion, and as it were a rule, that thēperour willing any thing to be done, ther is no more to be done, than the lawes permit to be done. For (saie they) neither pope, Emperour, nor king may doo any thing to the hurt of his people without their cōsent. King Antigonus Chauncelour, saieng vnto him, that all thinges were honest ād laufull to kinges: ye saie true (quod the king) but to suche kinges as be beastes, barbarous ād without humanitie: but to true ād good Princes, nothing is honest, but that is honest in dede, and nothing is iuste, but that is iuste in dede.

Anthiochus the thrid king of Asia, considering that as he was aboue the people, so the lawes were aboue him, wrote general lettres to all the cities of his countrey, that if they shoulde perceaue, that he by any lettres, should require any thing contrary to the lawes, they should thinke, that suche lettres were obteined without his cōsent, and therfore they should not obeie them.

Now if wher the people haue geuen their autoritie to their gouernour to make suche lawes, yet can he not breake or dispēse with the positiue lawes: how muche lesse maie suche gouernours, kinges, and princes to whō the people haue not geuen their autoritie (but they with the people, ād the people with thē ma ke the lawes) breake them or dispēse with them? If this were tolerable, thā were it in vaine to make solēne as semblies of the hole state, long Parliamentes &c? yea [30] (I beseche the) what certayntie should therbe in any thyng, wher all should depende on ones will and affection? But it wilbe saied, that albeit kinges and princes can not make lawes, but with the consent of the people, yet maie they dispense with any positiue lawe, by reason that of long tyme they haue vsed so to doo, and prescribe so to doo: for long custome maketh a lawe.

To this it maye be answered, euil customes (be they neuer so olde) are not to be suffred, but vtterly to be abolished: and non maie prescribe to doo euil, be he king or subiecte. If the lawes appoint thee the time of thrittye or fourtie yeares to claime a sure and a perfit interesse of that thow enioiest, yet if thow knowe, that either thy self or those by Whom thow claimest, came wrongfully by it, thow art not in dede a perfit owner of it, but art bounden to restore it. Although the lawes of man doo excuse and defende thee frō outwarde trouble and punishemēt, yet cā they not quiet the cōsciēce, but whā thy cōscience remēbreth, that thow enioiest that is not thyne, it will byte the that thow haste done wrong: it will accuse the before the iudgement seat of God, and condemnethe. And if princes and gouernours wolde shew thēselues half so wise, as they wolde men shoulde take them to be, and by thexample of others learne What mischief might happen to them selues, they wolde not (if they [31] might) clayme, muche lesse execute any suche absolute authoritie. No, neither wold their Counsailours (if they loued them) maintene them in it: nor yet the subiectes (if they did but considre their owne sauetie and felicitie in this life) wolde not if they might suffre their Prince to doo what him lusted.

For thone purchace to them selues a perpetuall vncertaintie bothe of life and goodes: and thother procureth the hatred of all, which albeit it be coloured and dissembled for a season, yet dothe it at leynght burst out, and worketh the reuenge with extremitie.

Ther lacke no examples to verifie this. It was dryven in to the head of temperour C. Caligula, that he was subiecte to no power, that he was aboue all lawes, and that he might laufully doo what him lu sted. This lesson was so swete to the fleshe, that it was no soner moued than desired, no soner taught than learned, no soner hearde than practiced. First by like that thempire should not goo out of his owne race, he coupleth not with one, but with all his susters, like bitche and dogge. He killeth his brother Tiberius, and all his chiefest frendes: he murdereth many of the Senatours of Rome. He delited to haue honest men to be garshed, scotched and cut in the faces, and so to make him pleasure, to haue them cast [32] to rauenous beastes to be torne and deuoured in his sight, or to be sawed asondre in the middes. It was a pleasunt pastyme for him, to see the parentes stande by, lamenting and weping, whiles their children were tormented and killed. He vsed to complayne and lament, that no common calamitie and notable miseries happened in his time. He reioyced muche whan newes were brought him of the slaughters of hole armies of men, great hongre, pestilence, townes burnyng, and openynges of the earthe, wherin many people were swalowed vp. But the daye he sawe any of these him self, he neded neither meat nor drinke, he was so iocunde and merye. And being glutted with the pastime of euery mannes deathe, by him self (to procure a newe appetite) he deuised an other, if he could haue brought it to passe. But whan he could not haue it done, the memorie therof was so swete, that he ofte desired: that is, that all the he addes of the people of Rome stode on one mannes necke, that he might with ones was he cut it of. Many other noble actes by his absolute power he wrought: and at leynght he commaunded that his ymage should be set vp in the temple at Ierusalem, and ther worshipped: as not vnlike Saīt Gardiners (for he hathe done no smal thīges) shalbe shortly by Anti cipaciō in Englād. But what was thende of Caligulaes absolute power? whā he had reigned three yeares and ten monethes, his owne householde seruaūtes [33] conspired against hym, and the general of his owne Armie slewe him.

Nero thēperour was of nature very modest, gen til, and mercifull, and the first fiue yeares of this reigne, he behaued him self very vertuously. After, other counsaillours and maisters, than Seneca crept into his fauour, who tolde him that he might doo what him lusted. He was sone persuaded therunto. And to shewe som profe that he had well caried awaye their aduise: he killed his mother Agrippina. This cruel acte did so moue his wicked conscience, that he durst not come abroade in the Senate, but kept him self secrete in his priuie chābre. For he feared the hatred of the people, and knewe not what was best for hī to doo. He lacked no flattering Counsailours. Ther were pleintie that sought their owne profit and gayne, and the satisfieng of their lustes, more than their princes honour and sauetie, and the cōmon wealthe of their coūtreie Saie they: Sir, whi should ye be thus amased with the deathe of this womā? She was of all people abhorred ād hated: the people wōderfully reioyce in your doīg, and cōmēde you aboue the moone for so noble an acte. They desire, that ye will returne in to the citie, that they maie with triumphe expresse how muche their ioie and gladnesse is, and how they loue you for so noble a feate. These craftie knaues seing how they might blinde their maisters eies, cōmaunded in themperours behalf, that all the people should come out of [34] Rome, to mete themperour. The Senate in their best apparail cometh out, alle other ordres likewise after their degrees folowe, and finally man, Woman and childe.

Themperour whan he sawe them, thought all was done from the botome of their heart. The Senate shewed suche outwarde honour, the commones so great loue, eueri body pretended so great ioye and gladnesse. And thinke ye, ther were not about him that said. Dothe not your Maiestie well finde all our saienges true? maye ye not credite vs in that we coun sail and aduise you? What folowed? Themperour embrewed with the blood of his mother, and his vnnatural acte commended by his wicked Counsailours, ceasseth not from his crueltie, but earnestly goeth forwarde He putteth awaie his wife Octauia, bicause she semed to be baren. He marieth his harlot called Puppie. He sendeth his wife Octauia in to an Ilan de, he byndeth her in chaines, and causeth her to be let blood in all partes: and fearing least feare wolde dryue the blood to the harte, and so she lyue longer than he wolde, he setteth her in a bayne of hotte water, that her blood might the soner come out. But what becometh of his deare dearling Puppie? he dalieth a while with his Puppie and at leynght his hotte loue being turned in to displeasur, he spurneth her (being with Childe) on the belye, and so she dieth. To late he repented, but yet ceassed not his crueltie. He killed [35] his maister Seneca, he persecuted the churche of Christ most miserably, and so thinking that he might doo what him lusted, and that all was well done, were it neuer so euil done, he neuer lefte of his crueltie, til the people finding occasion and oportunitie to vttre their dissembled hatred, slewe him.

But what thinke you? who were to be blamed for these cruell actes? He for doing thē, or others for flat tring hī, or the Senate ād people of Rome in suffring him? Surely ther is none of them to be excused, but all to be blamed, and chiefly those that might haue bridled him, and did not.

He is a good citezin, that dothe non euil (saieth a noble wiseman) but he is a better that letteth others, that they shall not doo hurt nor vniustice to others. The blood of innocentes shalbe demaunded not only at the handes of the sheaders of blood, but also of those that make or consent to wicked lawes, to condemne innocentes, or suffre their head to kill them contrary to iust lawes▪ or to spoile them of that they iustly enioie by the ordre of the lawe.

Now sithe kinges, princes, and gouernours of common wealthes haue not nor can iustly clayme any absolute autoritie, but that thende of their autoritie is determined and certain to maintene iustice, to defende the innocent, to punishe the euil. And that so many euilles and mischiefes maie folowe, wher such absolute and (in dede) tirānical power is vsurped: let vs praie, [36] that they maie knowe their duetie, and discharge thē selues to God and to the worlde, or elles that those which haue the autoritie to refourme them, maie know and doo their duetie, that the people finding and acknowlageing the benefite of good rulers, maie thāke God for them, and labour euery one to doo their duetie: and that seing the head is not spared, but euillesin it punished, they maie the more willingly absteine frō tyrānie and other euil doinges, and do their dueties, and so all glorifie God.

[37]

VVHETHER KINGES, princes, and other politike Gouernours be subiecte to Goddes lawes, and the positiue lawes of theyr countreyes.↩

HE that noteth the procedinges of princes and gouernours in these our daies, how ambicious they are to vsurpe others Dominiones, and how necli gēt they be to see their owne well gouerned, might thīke, hat they beleue, that either ther is no God, or that he hathe not care ouer the thīges of the worlde: or that they thinke themselues exempt frome Goddes lawes and power. But the Wonderfull ouerthrowe of their deuises (whan they thinke themselues most sure and certain) is so manifest, that it is not possible to denye, but that bothe ther is a God, and that he hathe care ouer the thinges of the worlde. And his worde is so playne, that non can gaynsaye, but that they be subiecte and ought to be obedient to Goddes lawes and Worde. For the hole decalog and euery part therof is aswell written to kinges, princes, and other publike persones, as to priuate persones. A king maye no more committe Idolatrie, than a priuat man: he maye not take the name of God in vayne, he maye not breake the Sabbat, no more than any priuate man. It is not laufull for him to disobeye his parētes, to killany persone contrary to the lawes, to be an hooremōger, [38] to steale, to lye and beare false witnesse, to desire and couet any mannes house, wife, seruaunt, mayde, oxe, asse, or any thing that is an others, more than any other priuate man. No, he is bounden and charged vnder greater paines to kepe them than any other, bicause he is bothe a priuate man in respecte of his owne persone, and a publike in respecte of his office, which maye appeare in a great meigny of places wherof parte I will recite. The holy gost by the mouthe of a king and prophet, saieth: And now ye kinges vnderstande, be ye learned that iudge the earthe. Serue the Lorde in feare, and reioi ce with trembling. Kisse the sonne, that is, receaue with honour, least the Lorde be angrie, and ye lose the waye, whan his wrathe shall in a moment be kyndled. And in an other place thus: The Lorde vpon thy right hāde shal Smyte and breake in pieces euē kinges in the daye of his wrathe. Esaias also the prophet saieth: The Lorde shal comme to iudgemēt against the princes and elders of the people. Likewise saieth the Prophet Micheas speaking to all princes and gouernours vnder the heades of the house of Iacob, and the leaders of the house of Israel: He are ye princes and gouernours, saieth Micheas: Should ye not kno we what were laufull and right? But ye hate the good, and loue the euil, ye plucke of [39] mēnes skynnes, and the fleshe from their bones: ye cheoppe them in pieces, as it were in to a Caldron, and as fleshe in to a potte. Now the tyme shall come, that whā ye call vnto the lorde, he shall not heare you, but hyde his face from you, by cause that through your owne ymaginationes ye haue dealt so wickedly. And again he saieth: O heare ye rulers and gouernours, ye that abhorre the thing that is lauful, and wraste asyde the thing that is straight: ye that builde vp Sion with blood your magestie and tirannie with doing Wrong. For so maie Sion and Ierusalem be well expounded: O you iudges, ye geue sentence for giftes: O ye priestes, ye teache for lucre: O ye {pro}phetes, ye prophecie for money: yet Will they be takē as those that holde vpō God, and saie▪ Is not the lorde amōg vs? How can than any mysfortune happen to vs? But Sion (that is, your cities) for your sakes shalbe plowed like a fielde: and Ierusalē (that is, your palaces) shall become an heape of stones, and the hill of the tēple (that is, your Monasteries, frieries, and chauntries) shall be come an high woodde. The holy goost also by the mouthe of king Salomon, sayeth: Heare O ye kinges, and vnderstande. O learne ye that [40] be iudges of the ēdes of the earthe. Geue eare ye that rule the multitudes, and delyte in muche people. For the power is geuē unto you of the lorde, ād the streinght from the highest, who shall trye your wor kes, and searche out your ymaginaciones, how that ye being officers of his kingdom haue not kept the lawe of righteousnesse nor Walked after his will. Horribly and that sone shall be appeare vnto you, for vpō the most high, he will execute most seuere iudgement. Mercie is graunted unto the simple, but they that be in autoritie, shalbe sore punished. For God which is lorde ouer all, shall except no mannes person, neither shall he regarde any mannes greatnes for he hathe made the small and greatand careth for all alike, but the mightie shall haue the sorer punishement. To you therfore (O princes) doo I speake, that ye maye learne wisdome, and not offende.

These saienges nede no particular examples to con firme them, but loke on all gouernours and rulers named in the hole Bible, or in any other historie: and among all ye shall finde, that non hathe escaped Goddes punishement, but alwayes their iniquitie hathe ben plaged in them selues or their posteritie.

The cause and maner of king Saules punishemēt [41] and extinguishing of his posteritie, is more commonly knowne, than nedeth any rehearsall. Roboam bicause he wold reigne as a tyranne and not be subiecte to lawe nor counsail, hade ten tribes of his kingdome taken frō him, and geuen to Ieroboam: who also forasmuche as he contented not him selfe to be sub iecte to Goddes written worde and lawe, but fell to his owne Idolatrous inuenciones, and caused his subiectes to folowe his procedinges: was so stripped from the enheritaunce of his crowne, that his sede was vtterly rooted out.

The ende of Achab and Iesabel is well ynough vnderstanden. And kyng Ioram for his stout stryuing against Goddes lawes and the ordre of his countrey was so sore striken of the lorde with horrible diseases, that at leynght his guttes for extreme anguishe flewe out of his bely. But wherto bring I out particular examples of Goddes plagues and punishementes vpon kinges and princes that wold not be subiecte to Goddes lawes, and the lawes of nature, seing the hole body of the Bible, and writers of prophane histories be full of them?

Therfore seing no king or gouernour is exempted from the lawes, hande, and power of God, but that he ought to feare and tremble at it, we maye procede to the other part of the question: that is, whether kinges, princes, and other gouernours ought to [42] be obedient and subiecte to the positiue lawes of their countrey. To discusse this question, the right waye and meane is as in all other thinges, to resorte to the fountaynes and rootes, and not to depende on the ryuers and braunches. For as if men should admyt, that the churche of Rome were the catholike churche, and the pope the head of it, and Goddes onely vicare in earthe, and not seke further how he cometh by that autoritie: than could noman saie, but that all his doinges (were they neuer so wicked) should seme iust: so if men should buylde vpon thauthoritie that kinges and princes vsurpe ouer their subiectes, and not seke from whens they haue theyr autoritie, nor whether that which they vse, be iuste, ther could be nothing produced to let their cruell tyrannye. But for asmuche as we see from whence all politike power and autoritie cometh, that is, from God: and why it was ordained, that is, to mayntene iustice: we ought (if we will iudge rightly) by Goddes worde examine to trie this mater.

Saint Paule treating who should doo obedience, and to whom obedience should be done, saieth: Let euery soule be subiecte to the powers that rule, for ther is no power but of God. Ther are that wolde haue this worde, Soule, taken for man, not as he consisteth of soule and body bothe together, but onely of the fleshe: and that so by the wor de (Soule) should be vnderstanden onely a worldly man, that is, a laye man or temporall man (as we terme [43] it) and not a spiritual man and a minister of the churche. Wher vpon Antichrist, the bishop of Ro me seking for subiectes to be vnder his kingdom, hathe takē for his subiectes the cleargie with tagge and ragge that to them belongeth: and hathe made lawes, that they should be his subiectes, obedient to him and not to the politike power and autoritie, wher vnto he leaueth for subiectes onely the temporaltie.

But in scripture this worde (Soule) is taken for euery kinde of mā, as may appeare whā it saieth, that all the soules (that is, man and womā) that were in the arke with Noe, were eight. And that all the soules of the house of Iacob, which cam in to Egipt were lxx. In which nombres it can not be denyed, but that ther were as holy and as spirituall persones, as any are or were in the kingdome of the bishop of Rome. And Chrisostome (a priest) expounding this texte (Let euery soule be subiecte to the higher powers) sayeth: yea if thow be an apostle, an euangelist, a prophet, or what so euer thow art: for this subiection destroieth not religion. So that it can not be denyed, but by this worde (Soule) is comprehended, euery persone, and none excepted. Now touching this worde (Power) some wold haue it interpreted for all those persones that execute iustice, be he kaiser, king, mayre, Sherif, constable, borseholder, or neuer so lowe: and some wolde haue it to be interpreted only of kinges ād chiefest officers. But it is here to be [44] taken for the ministerie and autoritie, that all officers of iustice doo execute: and so it maie appeare by Chri stes owne wordes, wher he saieth: The kinges of the naciones rule ouer▪ thē, ād those that ex ercice thautoritie or power, be called gracious Benefactours, or well doers. For as all mē and womē that seme to lyue together in the ho ly ordinaunce of Matrimonie, be not mā and wife, for it maie be, that the man hathe an other wife liuing or the wife other an husbande, or that they came not together▪ for the loue of God only, and to auoide sinne, but for sensualitie, and to get riches, and so thordinaunce it self is one thing, and the persones, that is, the mā ād womon an other: euē so is the politike power or autoritie beīg thordinaūce ād▪ good gifte of God, one thīg, ād the {per}sone that executeth the same (be he kīng or kaiser) an other thing. The ordinaūce being godly, the mā may be euil ād not of God, nor come therto by God, as the Prophet Osee saieth: They haue made them a king, and not through me: a prince, and not through my counsail and will,

Neither is that power and authoritie which kinges, princes, and other ministres of iustice exercice, only called a power: but also thauthoritie that paren tes haue ouer their children, and maisters ouer their seruauntes, is also called a power: and neither be the parentes nor maisters the power it self, but they be inistres and executours of the power, being geuen [45] vnto them by God: Which also S. Paule in an other place plainly sheweth, saieng to Titus: Warne them to be subiecte to the principalities ād powers. Which some interprete, princes and powers, to make a distinctiō betwene the minister and the Ministerie. And it foloweth: to obey thofficers, so that alwaies the difference maie be perceaued. So than if by this worde (Soule) is ment euery person spiritual and temporal, man and woman: and by this worde (power) thautoritie that kinges and princes execute, than can not kinges and princes, but be conteined vnder this general worde (Soule) as well as others. And they being but executours of Goddes lawes, and mennes iust ordinaunces, be also not exempted from them, but be bounden to be subiecte and obe dient vnto them. For good and iuste lawes of man be Goddes power and ordinaunces, and they are but ministers of the lawes, ād not the lawes self. And if they were exēpt from the lawes, and so it were laufull for them to doo what them lusteth, their autoritie beīg of God, it might be saied, that God allowed their tyrānie robbery of their subiectes, killīg thē without lawe, ād so God thautor of euil: which were a great blasphemie. Iustiniā thēperour well cōsidered, whan he ma de this saieng to be put into the body of the lawes. It is a worthy saieng (saieth he) for the Maiestie of him that is ī autoritie, to cōfesse that the prīce is subiecte to the lawes, thauthoritie of the prīce do the so muche [46] depende on thautoritie of the lawes. And certainly it is more honour than the honour of the empire, to submitte the principalitie vnto the lawes. For in dede lawes be made, that the wilfull self will of men should not rule, but that they should haue a line to leade them, as they might not goo out of the waie of iustice: and that (if any wolde saie, they did them wrong) they might alledge the lawe for their waraunt and autoritie. It is also a principle of all lawes grounded on the lawe of nature, that euery man should vse himself and be obedient to that lawe, that he will others be bounden vnto. For otherwise he taketh awaye that equalitie (for ther is no difference betwene the head and foote, concerning the vse and benefite of the lawes) wherby common wealthes be maintened and kept vp. What equalitie (I beseche you) should ther be, wher the subiecte should doo to his ruler all the ruler wolde: and the ruler to the subiecte, that the ruler lusted?

The good emperour Traianus (whom for his iust behaueour, the Senate of Rome toke to be a God) being in possession of his office, and minding to shewe, that he was not ordained to be a tiranne, but to see the people well gouerned, and that, albeit he was the minister of the lawes, yet was he subiecte to the lawes, toke a sweorde, and gaue it to the Captain of the horsemen, and saied: Take this sweorde, use it for me against [47] mine enemies in iust causes: and if I my self doo not iustly use it, than use it against me.

Zaleuchus the ruler and maker of lawes to the locres, whan he made this lawe, that an aduouterour should be punished with the losse of bothe his eies, and his sonne hade offended the same, albeit the people made great intercession, that his paines might be pardoned him, he wold not consent vnto it, but pul ling out one of his sonnes eies, to fulfill and kepe the lawe, he suffred one of his owne eies also to be pulled out.

But thow wilt saie: What haue we to doo with Ethnikes? Why should we be ordred by Ethnikes doinges? I answer, that whan Ethnikes doo by nature that thow art bounden also to doo, not only by nature, but by the lawes of God and man, such Ethnikes shall ryse in the vniuersal iudgement, to accuse the, and worke thy condemnacion. The bishop of Romes lawes (which albeit he vse not in him self, yet will he haue them practiced in others) saye thus: It is requisite and iust, that a prince obeie his owne lawes. For than maie he loke that others shall kepe his lawes, whan he him self hathe them in honour. Iustice will, that princes be obedient aud bounden to their owne lawes, and that they can not in their owne doinges condemne [48] those lawes which they prescribe unto others. Thauthoritie of their sayeng is iust and indifferent, if that thei suffre not them selues to doo that they prohibite unto their people. This saieth the bishop of Romes lawe. And vpon this principle after in the great general counsail of Lateran, Which pope Innocent the thirde helde, it may seme, it was ordained and decreed (as they saie) that whan kinges and princes that knowlaged no superiour, should fall out among them selues, or should misuse their power and autoritie ouer their subiecttes, that than the matier should be hearde ād corrected by the bishop of Rome

But here it maie be asked, who did this iustice on kinges and princes before that time, sith it was but than cōmitted to the bishop of Rome? To that at this time we shall not nede to answer, for that we doo not seke presētly to knowe who should be iudge, but onely to declare and proue, that kinges and princes ought, bothe by Goddes lawe, the lawe of nature, mannes lawes, and good reason, to be obedient and subiecte to the positiue lawes of their countrey, and maie not breake▪ them, and that they be not exempt from them, nor maie dispense with them, onles the makers of the lawes geue them expresse autoritie so to doo.

Who shalbe the kinges iudges, hereafter thow shalt heare.

[49]

IN WHAT THINGES, AND how farre subiectes are bounden to obeie their princes and gouernours.↩

AS THE BODY OF MAN IS KNIT and kept together in due proporciō by the sinewes, so is euery cōmū wealthe kept ād maìtened in good ordre by Obedience. But as if the sinowes be to muche racked ād stretched out, or to muched shrinked together, it briedeth wonderfull paines and deformitie in mānes body: so if Obediēce be to muche or to litell in a common wealthe, it causeth muche euil and disordre. For to muche maketh the gouernours to for get their vocacion, and to usurpe vpon their subiectes: to litel briedeth a licencious libertie, and maketh the people to forget their duetie. And so bothe waies the common wealthe groweth out of ordre, and at leinght cometh to hauocke and vttre destruction,

Some ther be that will haue to littel obedience, as the Anabaptistes. For they bicause they heare of a christian libertie, wolde haue all politike power taken awaye: and so in dede no obedience.

Others (as thenglishe papistes) racke and stretche out obedience to muche, and wil nedes haue ciuile power obeied in all thinges, and that [50] what so euer it commaundeth, without respecte it ought and must be done. But bothe of them be in great errours. For thanabaptistes mistake christian libertie, thinking that men maye liue without sinne, and forget the fall of man, wherby he was brought in to suche miserie, that he is no more hable to rule himself by him self, than one beast is hable to rule an other: and that therfore God ordained ciuile power (his ministre) to rule him, and to call him backe, whan so euer he should passe the limites of his duetie, and wold that an obedience should be geuen vnto him.

And the papistes neither considre the degrees of powers, nor ouer what thinges ciuile power hathe autoritie, ne yet how farre subiectes ought to obeye their gouernours. And this they doo not for lacke of knowlage, but of a spiritual malice, bicause it maketh against their purpose, that the truthe should be disclosed.

If any christian prince should goo about to redresse the abuses of the Sacraments (brought in and deuised by the papistes to maintēe their kingdome) to correcte their abominable life, their hooredome, buggery, dronkenesse, pride, and suche like vices: than is he an other Ozias, an other Osa, an heretike, aschismatike, cursed from toppe to too, with boke, bell, and candle, as blacke as a potteside: no obedience of the subiectes ought to be geuen vnto him. But if [51] he be contented to wynke at their abominaciones, to runne with them, to dishonour God, to commit idolatrie, to kill the true ministers and confessours of Christ, to destroye the poore innocētes which abhor the papistes wicked vices, and be desirous that Goddes kingdome should be promoted: than is he an other Ezechias, a Iosias, a catholike prince, a deare sonne of the churche, the protectour of the churche, the defendour of the faithe, the fosterour of the churche, a confessour while he lyueth, after his deathe a saynt (yea a saint deuil) canonized with Ora pro nobis: whan Beelzebub daunceth at his Dirige.

Suche a one (saie they) must be obeyed in all thinges, none maie speake against his procedinges, for he that resisteth the power, resisteth thordinaunce of God, and he that resisteth, purchaceth to him self dam naciō: as though to leaue euil vndone, and to doo good, were to resi ste the power. And here also they wryng this sayeng of S. Petre (Seruauntes obeie your maisters, although they be froward and churlishe) to free subiectes vnder a king: as if bounde men and free men were all one, and kinges and bondemens lordes hade like authoritie. So with violent wringing and false applyeng of Goddes healthe geuing worde, Caiphas and Herode ryde cheke by cheke, and walke arme in arme, with bothe the sweor des and crosse before them. Frende to the one, frende [52] to bothe: and he that is an heretike with Caiphas, must be atraitour to Herode▪

Thus they goo about to bleare mennes eies to con firme and encreace their deuillishe kingdome. But popis he prelates practices are no warraunt to discharge a christian mannes conscience. He must seke what God will haue him doo, and not what the subtiltie and violēce of wicked men will force him to doo. He maye not robbe petre to clothe Paule, nor take from God his due to geue it vnto ciuile power: neither maie he make confusion of the powers, but yelde vnto euery one that is his due, nor yet obeyeng the inferiours commaundement, leaue the commaundement of the highest vndone. Yelde vnto Cesar, those thinges that be Cesares (sayeth Christ) and vnto God, those thinges that be Goddes. Ciuile power is a power and ordinaunce of God, appointed to certain thinges, but no general minister ouer all thinges. God hathe not geuen it power ouer the one and the best parte of man, that is, the soule and conscience of man, but onely ouer the other and the worst part of man, that is, the body, and those thinges that belong vnto this temporall life of man.

And yet ouer that parte with thappurtenaunces hathe he not only not geuen man the hole power, and [53] stripped him self quite of all thautoritie, but also he hathe reserued to him self the power therof. For we reade, that whan ciuile power (his minister) hathe ben necligent in doing his duetie, or winked at the euil life of the people, God hathe not holden his hande, but hathe whipped and plagued suche people, as he did the Sodomites, Gomorrianes, and diuerse tymes the Iewes.

And in our dayes his hāde is not shortened but he hathe and daily dothe plage blasphemours, hooremongers, dronkerdes, murtherours, theues, traitours, tyrannes, suche as in mannes sight no man durst or at the least wolde touche: som with incurable plages of their bodye, some with losse of their children, some with losse of their goodes, and some with shamefull deathes.

And contrary wise whan the worldly powers haue violently, tyrannously, ouer sharply, and wrongfully oppressed and condemned innocentes, God (to testifie that he hathe also power of the body) hathe many tymes in all ages myghtily and miraculously deliuered his people from the power of tyrannes: as the Israelites from Pharao, Mardocheus from A man, Susanna from the lecherous iudges: Sedrach Mesach, and Abednego srō the burnyng ouen: Daniel from the lyons denne, Petre from Herode, and infinite other examples we [54] haue in scriptures and histories. And the like haue not wanted in our daies also, if we will aduisedly cōsidre the condicion and state of our tyme. So that we see God to be the supreme power of the hole man, aswell to punishe as to deliuer at his owne will.

God is the highest power, yea the power of powers, frō him is deriued all power. All people be his seruaūtes made to serue and glorifie him. All other powers are but his ministers, set to ouersee that euery one he haue him selfe, as he ought towarde God, and to doo those thinges, that he is iustly commaunded to doo, by God.

What so euer God commaundeth man to doo, he ought not to considre the mater, but straight to obeie the commaunder. For we are sure, what he commaundeth, is iust and right: for from him that is all together iuste and right, no iniustice nor wrong can come.

So did Abraham, whan contrary to that semed to be right and iust (yea contrary to Goddes general commaundement) he made himself ready to kill and offre in sacrifice his onely promised sonne Isaac, according to Goddes special commaundement. So did also the children of Israel, contrary to the general commaundement (Thou shalt not steale) robbe and spoile the Egipcianes, by Goddes special commaundement. And so did Phinees, who albeit he [55] were no Magistrate, yet of a great zeale by the inward mocion of Goddes spirit thrust his sweorde through those two whom he founde committing Horedome,

But cōtrary in maānes cōmaundementes, men ought to considre the matier, and not the man. For all men what so euer mynisterie or vocatiō they exercice, are but mē, and so maye erre. We see coūcelles against cōcelles, parliamētes against parliamētes, cōmaundemēt against cōmaundement, this daye one thing to morow an other. It is not the mannes waraunt that can discharge the, but it is the thing it self that must iustifie thee. It is the mater that will accuse thee, and defende thee: acquyte thee, and condemne thee: whan thou shalt come hefore the throne of the highest and euerlasting power, wher no temporal power will appeare for thee, to make answer or to defende thee: but thou thy self must answer for thy self, and for what so euer thou hast done. And therfore christen men ought well to considre, and weighe mennes commaundementes, before they be hastie to doo them, to see if they be contrarie or repugnaunt to Goddes commaundementes and iustice: which if they be, they are cruell and euill, and ought not to be obeyed. We haue this special commaundement from God the highest power, ofte repeted by the holy goost. Forbeare to doo euil, and doo that is good. [56] S. Paule (the true teacher of obediēce) teacheth, that ciuile power and princes be not ordayned to be a ter rour to those that doo wel but to those that doo euil, ād will not that mē should do what so euer the power commaundeth, but sayeth, wilt thou not feare the power? doo that is good, and thou shalt haue praise of it: for it is the minister of God ordained for thy benefite, and not to thy destruction. But if thou doo that is euil, than feare: for it carieth not the sweorde in vayne: for it is the minister of God, a reuenger and execucionar, to punishe him that shal doo euil. And therfore it is orday ned, that euil might be taken awaye. Men must be sub iecte, not only for feare of punishement, but also for conscience sake. For not to obeye the power, that defendeth the good and vertuous, and punisheth the euil and wicked, is deadly synne, And the self same also S. Petreteacheth. Wherfore the marke that all men ought to shoote at, is to doo good, and in no wise to doo euil, whoso euer commaundeth it. If the ministers of the ciuile power commaunde thee to honour and glorifie God, as God wilbe honoured, to defende (with thy persone and goodes) thy countreye against thenemies, to doo suche thinges as be for the wealthe and benefite of thy countreye: thou art bounden to doo it: for it is good, and God will haue thee to doo it. And if thou doo it not, thou synnest against [57] God, and iustly deseruest the punishement not only of the power, but of euerlasting damnacion But if the ministers of the ciuile power commaunde thee to dishonour God, to committe idolatrie, to kill an innocent, to fight against thy countrey, to geue or lende that thou hast, to suche as mynde the subuersion and destruction of thy countrey, or to mayntene them in their Wickednesse, tkou oughtest not to doo it, but to leaue it vndone: for it is euil, and God (the supreme ād highest power) will not that thou shouldest doo it. Thapostles in tyme of persecution did not onely geue vs an example so to doo, whan the worldly powers wolde haue had them to folowe their procedinges, but also lefte vs a lessō so to doo. God must be obeied (saye they) rather than men. And this lesson euen from the begynning before it was written, was by the holy goost printed in mānes heart. Whan Pharao the tyranne commaunded the mydwyues of the Egipcianes, to kill all the male children that should be borne of the Israelites wyues: thinke ye, he did only commaunde them? No without doubt. Ye maye be sure, he commaunded not only vpō threatned paynes, but also pro mised them largely: and perchaunce as largely as those doo, that being desirous of chidren, procure the mydwyues to saye, they be with childe, whan their bely is puffed vp with the dropsie or molle, ād hauing bleared the cōmon peoples eies with processioning, Te deum singing, and bonefire banketting, vse all cere [58] monies and cryeng out, whilest an other birdes egge is layed in the nest. But these good mydwiues fearing God (the high power) who hadde commaunded them, not to kill, wolde not obeye this tyranne Pharaoes commaundement, but lefte it vndone.

Whan the Ioilye quene Iesabel commaunded, that the prophetes of God should be destroyed, that noen should be lefte to speake against her idoles, but that all men should folowe her procedinges: did Abdias the chief officer to the king her husbande saye, your grace dothe very well to ridde the worlde of thē for those that worship the true liuing God, cannot be but traitours to my souerayne lorde and maistre the king your husbande, and to your grace: and it is these heretikes, that bewitche and coniure you, that your grace cannot be delyuered of your childe, nor slepe quietly in your bedde: let me alone, I will finde the meanes to despeche them all, only haue your grace a good opinion of me, and thinke I am your owne? No. Abdias (a man fearing God, and knowing this commaundement to be a wicked womans will) did cleane contrary to her commaundement, and hidde and preserued an hundred of the prophetes vnder the earthe in caues. Whan the wicked king Saul commaunded his howne householde wayters and familiar seruaun tes to kill the priest Ahimelech and his children for hatred to Dauid: did those his owne nerest wayting seruauntes flattre him forewarde, and saye: your [59] Maiestie shall neuer be in sauetie and quiet so long as this traitour and his prating children (that are alwayes in their sermones and bokes, meddling of the kinges maters) be suffred to lyue? we wilbe your true obedient seruauntes, we will beleue as the king beleueth, we will doo as the king biddeth vs, according to our most bounden duetie of allegeaunce, we shall sone ease your highnesse of this grief: other of your graces chaplaynes be more mete for that rowme than this hipocrite traitour? No. they vsed no suche court crueltie, but considering God to be the supreme power, and seing Ahimelech (by his answeres) and his householde to be giltles of suche mater in forme and intent as (by Doeges accusation) Saul charged him with all, they refused to kill any of them, or ones tolaye violent handes vpon them, but playnly and vtterly (being yet the kinges true seruauntes and subiectes) denyed to obeye the kinges vnlaufull commaundement. And whan the same hipocrite Saul commaunded his seruauntes or souldiours to kill noble Ionathas his sonne, who for necessitie hade taken a litel honie to recouer his streinght contrary to the king his fathers commaundement: did they saie, let vs kill him as we be willed, so shall some of vs be made the kinges lieutenaunt, we shalbe an ynche nerer to the succession, we shall haue his landes, possessiones, goodes and offices parted [60] amōg vs: let vs not sticke to doo it. Whan he is despe ched out of the worlde, he can make no reuenge, for dead men doo no harme. No, no, cleane cōtrary. They knewe that innocent Abels bloud did crie to the lorde, Vengeaunce, uengeaunce, uengeaunce. And that albeit Cain hade a marke, that no man might laufully kill him in this life, yet hangeth he now (as good writers saie) in chaines in hell. And thefore they wolde not obeie the wicked and cruel tirannes commaundement, but knowing that God will not haue innocentes blood shead, but innocentes against tyrannes defended, they toke vpon them the defense of the good sonne against the tyrannicall hipocrite and vnnatural father.